New York Draft Riots of 1863 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of white working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to Conscription in the United States, draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and most racially charged List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States, urban disturbance in American history. (updated ed. 2014, ). According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" inside the Irish Catholic community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly Irish working-class men who did not want to fight in the Civil War and resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 ( though a typical laborer's wage was between $1.00 and $2.00 a day in 1863) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a Mass racial violence in the United States, race riot, with white rioters attacking black people, in violence throughout the city. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that, "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was Arson, burned to the ground. The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of white working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to Conscription in the United States, draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and most racially charged List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States, urban disturbance in American history. (updated ed. 2014, ). According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" inside the Irish Catholic community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly Irish working-class men who did not want to fight in the Civil War and resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 ( though a typical laborer's wage was between $1.00 and $2.00 a day in 1863) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a Mass racial violence in the United States, race riot, with white rioters attacking black people, in violence throughout the city. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that, "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was Arson, burned to the ground. The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.

New York Historical Society (November 17, 2006 to September 3, 2007, physical exhibit); accessed May 10, 2012. The city was also a continuing destination of immigrants. Since the 1840s, most were from Ireland and Germany. In 1860, nearly 25 percent of the New York City population was German-born, and many did not speak English. During the 1840s and 1850s, journalists had published sensational accounts, directed at the white working class, dramatizing the evils of interracial socializing, relationships, and marriages. Reformers joined the effort. Newspapers carried derogatory portrayals of black people and ridiculed "black aspirations for equal rights in voting, education, and employment". The Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party's Tammany Hall political machine had been working to enroll immigrants as U.S. citizens so they could vote in local elections and had strongly recruited Irish. In March 1863, with the war continuing, Congress passed the Enrollment Act to establish a draft for the first time, as more troops were needed. In New York City and other locations, new citizens learned they were expected to register for the draft to fight for their new country. Black men were excluded from the draft as they were largely not considered citizens, and wealthier white men could pay for substitutes. New York political offices, including the mayor, were historically held by Democrats before the war, but the election of Abraham Lincoln as president had demonstrated the rise in Republican political power nationally. Newly elected New York City Republican Mayor George Opdyke was mired in profiteering scandals in the months leading up to the riots. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 alarmed much of the white working class in New York, who feared that freed slaves would migrate to the city and add further competition to the labor market. There had already been tensions between black and white workers since the 1850s, particularly at the docks, with free blacks and immigrants competing for low-wage jobs in the city. In March 1863, white Stevedore, longshoremen refused to work with black laborers and rioted, attacking 200 black men.

There were reports of rioting in Buffalo, New York, and certain other cities, but the first drawing of draft numbers—on July 11, 1863—occurred peaceably in Manhattan. The second drawing was held on Monday, July 13, 1863, ten days after the Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg. At 10 a.m., a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the "Black Joke"), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place.

The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, burst through the doors, and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses that were pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut Telegraphy, telegraph lines.

Since the New York Guard, New York State Militia had been sent to assist Union troops at Gettysburg campaign, Gettysburg, the local New York City Police Department, New York Metropolitan Police Department was the only force on hand to try to suppress the riots. Police Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy, John Kennedy arrived at the site on Monday to check on the situation. Although he was not in uniform, people in the mob recognized him and attacked him. Kennedy was left nearly unconscious, his face bruised and cut, his eye injured, his lips swollen, and his hand cut with a knife. He had been beaten to a mass of bruises and blood all over his body.

Police drew their Club (weapon), clubs and revolvers and charged the crowd but were overpowered. The police were badly outnumbered and unable to quell the riots, but they kept the rioting out of Lower Manhattan below Union Square (New York City), Union Square. Inhabitants of the "Bloody Sixth" Ward, around the South Street Seaport and Five Points (Manhattan), Five Points areas, refrained from involvement in the rioting. The 19th Company/1st Battalion US Army Invalid Corps which was part of the Provost Guard tried to disperse the mob with a volley of gunfire but were overwhelmed and suffered over 14 injured with 1 soldier missing (believed killed).

There were reports of rioting in Buffalo, New York, and certain other cities, but the first drawing of draft numbers—on July 11, 1863—occurred peaceably in Manhattan. The second drawing was held on Monday, July 13, 1863, ten days after the Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg. At 10 a.m., a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the "Black Joke"), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place.

The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, burst through the doors, and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses that were pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut Telegraphy, telegraph lines.

Since the New York Guard, New York State Militia had been sent to assist Union troops at Gettysburg campaign, Gettysburg, the local New York City Police Department, New York Metropolitan Police Department was the only force on hand to try to suppress the riots. Police Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy, John Kennedy arrived at the site on Monday to check on the situation. Although he was not in uniform, people in the mob recognized him and attacked him. Kennedy was left nearly unconscious, his face bruised and cut, his eye injured, his lips swollen, and his hand cut with a knife. He had been beaten to a mass of bruises and blood all over his body.

Police drew their Club (weapon), clubs and revolvers and charged the crowd but were overpowered. The police were badly outnumbered and unable to quell the riots, but they kept the rioting out of Lower Manhattan below Union Square (New York City), Union Square. Inhabitants of the "Bloody Sixth" Ward, around the South Street Seaport and Five Points (Manhattan), Five Points areas, refrained from involvement in the rioting. The 19th Company/1st Battalion US Army Invalid Corps which was part of the Provost Guard tried to disperse the mob with a volley of gunfire but were overwhelmed and suffered over 14 injured with 1 soldier missing (believed killed).

The Bull's Head hotel on 44th Street, which refused to provide alcohol to the rioters, was burned. The mayor's residence on Fifth Avenue was spared by words of Judge George G. Barnard, George Gardner Barnard, and the crowd of about 500 turned to another location of pillage. The Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. Other targets included the office of the ''New York Times''. The mob was turned back at the ''Times'' office by staff manning Gatling guns, including ''Times'' founder Henry Jarvis Raymond. Fire engine companies responded, but some firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters because they had also been drafted on Saturday. The ''New-York Tribune, New York Tribune'' was attacked, being looted and burned; not until police arrived and extinguished the flames, dispersing the crowd. Later in the afternoon, authorities shot and killed a man as a crowd attacked the armory at Second Avenue (Manhattan), Second Avenue and 21st Street. The mob broke all the windows with paving stones ripped from the street. The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black civilians, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then Lynching, lynched, hanged from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum at 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue, a "symbol of white charity to blacks and of black upward mobility" that provided shelter for 233 children, was attacked by a mob at around 4 p.m. A mob of several thousand, including many women and children, looted the building of its food and supplies. However, the police were able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow the orphans to escape before the building burned down. Throughout the areas of rioting, mobs attacked and killed numerous black civilians and destroyed their known homes and businesses, such as James McCune Smith's pharmacy at 93 West Broadway, believed to be the first owned by a black man in the United States.

Near the midtown docks, tensions brewing since the mid-1850s boiled over. As recently as March 1863, white employers had hired black longshoremen, with whom many White men refused to work. Rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers" to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from the area near the docks. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to black people. Mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

The Bull's Head hotel on 44th Street, which refused to provide alcohol to the rioters, was burned. The mayor's residence on Fifth Avenue was spared by words of Judge George G. Barnard, George Gardner Barnard, and the crowd of about 500 turned to another location of pillage. The Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. Other targets included the office of the ''New York Times''. The mob was turned back at the ''Times'' office by staff manning Gatling guns, including ''Times'' founder Henry Jarvis Raymond. Fire engine companies responded, but some firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters because they had also been drafted on Saturday. The ''New-York Tribune, New York Tribune'' was attacked, being looted and burned; not until police arrived and extinguished the flames, dispersing the crowd. Later in the afternoon, authorities shot and killed a man as a crowd attacked the armory at Second Avenue (Manhattan), Second Avenue and 21st Street. The mob broke all the windows with paving stones ripped from the street. The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black civilians, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then Lynching, lynched, hanged from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum at 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue, a "symbol of white charity to blacks and of black upward mobility" that provided shelter for 233 children, was attacked by a mob at around 4 p.m. A mob of several thousand, including many women and children, looted the building of its food and supplies. However, the police were able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow the orphans to escape before the building burned down. Throughout the areas of rioting, mobs attacked and killed numerous black civilians and destroyed their known homes and businesses, such as James McCune Smith's pharmacy at 93 West Broadway, believed to be the first owned by a black man in the United States.

Near the midtown docks, tensions brewing since the mid-1850s boiled over. As recently as March 1863, white employers had hired black longshoremen, with whom many White men refused to work. Rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers" to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from the area near the docks. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to black people. Mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

New York City Police Commissioner#Commissioners, Commissioners Thomas Coxon Acton and John G. Bergen took command when Kennedy was seriously injured by a mob during the early stages of the riots.

Of the NYPD Officers-there were four fatalities-1 killed and 3 died of injuries

''The Great Riots of New York, 1712 to 1863'' – including and full and complete account of the Four Days' Draft Riot of 1863.

E.B. Treat (publisher), stereotyped at the Women's Printing House * * * * *

online

* Cohen, Joanna (2022). "doi:10.1093/jahist/jaac118, Reckoning with the Riots: Property, Belongings, and the Challenge to Value in Civil War America". ''Journal of American History''. 109 (1): 68–98. * Geary, James W. "Civil War Conscription in the North: a historiographical review." ''Civil War History'' 32.3 (1986): 208–228. * Hauptman, Laurence M. "John E. Wool and the New York City draft riots of 1863: a reassessment." ''Civil War History'' 49.4 (2003): 370–387. * Joyce, Toby. "The New York draft riots of 1863: an Irish civil war?" ''History Ireland'' 11.2 (2003): 22–27

online

* Man Jr, Albon P. "Labor competition and the New York draft riots of 1863." ''Journal of Negro History'' 36.4 (1951): 375–405. On Black role

online

* Moss, Hilary. "All the World’s New York, All New York’sa Stage: Drama, Draft Riots, and Democracy in the Mid-Nineteenth Century" ''Journal of Urban History'' (2009) 35#7 pp. 1067–1072; DOI: 10.1177/0096144209347095 * Perri, Timothy J. “The Economics of US Civil War Conscription.” ''American Law and Economics Review'' 10#2 (2008), pp. 424–53

online

* Peterson, Carla L. "African Americans and the New York Draft Riots: Memory and Reconciliation in America’s Civil War." ''Nanzan review of American studies: a journal of Center for American Studies'' v27 (2005): 1–14

online

* Quigley, David. '' Second Founding: New York City, Reconstruction, and the Making of American Democracy'' (Hill and Wang, 2004

excerpt

* Quinn, Peter. 1995 ''Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York''. New York: Fordham University Press (fictional account of Draft Riots) * Rutkowski, Alice. "Gender, genre, race, and nation: The 1863 New York City draft riots." ''Studies in the Literary Imagination'' 40.2 (2007): 111+. * Walkowitz, Daniel J. "‘The Gangs of New York’: The mean streets in history." ''History Workshop Journal'' 56#1 (2003

online

* Wells, Jonathan Daniel. "Inventing White Supremacy: Race, Print Culture, and the Civil War Draft Riots." ''Civil War History'' 68.1 (2022): 42–80.

In JSTOR

* * ''New York Evangelist'' (1830–1902); July 23, 1863; pp. 30, 33; APS Online, pg. 4. *

online

''Report of the Committee of merchants for the relief of colored people, suffering from the late riots in the city of New York''. New York: G. A. Whitehorne, 1863

African American Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress.

''New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War Online Exhibit''

New York Historical Society, (November 17, 2006 – September 3, 2007, physical exhibit)

2002, source Civil War Society's ''Civil War Encyclopedia'', Civil War Home website

First Edition Harper's News Report, sonofthesouth.net

"1863 New York City Draft Riots"

mrlincolnandnewyork.org

Bill Bigelow, "The Draft Riot Mystery"

9-page lesson plan for High School Students, 2012, Zinn Education Project/Teaching for Change {{good article 1863 in New York (state) 1863 riots African Americans in the American Civil War Anti-war protests in the United States Conscription in the United States Irish-American history Massacres in the United States Military history of New York City Military history of New York (state) New York (state) in the American Civil War Political riots in the United States Racially motivated violence against African Americans Riots and civil disorder in New York City Riots and civil unrest during the American Civil War White American riots in the United States Protests in New York (state) Working class in the United States July 1863 events 1860s in New York City, Draft riots 19th century in Manhattan Mass murder in 1863 Riots and civil disorder in New York (state) 1863 murders in the United States Rebellions in the United States Working-class culture in New York City

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of white working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to Conscription in the United States, draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and most racially charged List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States, urban disturbance in American history. (updated ed. 2014, ). According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" inside the Irish Catholic community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly Irish working-class men who did not want to fight in the Civil War and resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 ( though a typical laborer's wage was between $1.00 and $2.00 a day in 1863) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a Mass racial violence in the United States, race riot, with white rioters attacking black people, in violence throughout the city. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that, "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was Arson, burned to the ground. The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.

The New York City draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), sometimes referred to as the Manhattan draft riots and known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of white working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to Conscription in the United States, draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and most racially charged List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States, urban disturbance in American history. (updated ed. 2014, ). According to Toby Joyce, the riot represented a "civil war" inside the Irish Catholic community, in that "mostly Irish American rioters confronted police, [while] soldiers, and pro-war politicians ... were also to a considerable extent from the local Irish immigrant community."

President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly Irish working-class men who did not want to fight in the Civil War and resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 ( though a typical laborer's wage was between $1.00 and $2.00 a day in 1863) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a Mass racial violence in the United States, race riot, with white rioters attacking black people, in violence throughout the city. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that, "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."

The military did not reach the city until the second day of rioting, by which time the mobs had ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was Arson, burned to the ground. The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many black residents left Manhattan permanently with many moving to Brooklyn. By 1865, the black population had fallen below 11,000 for the first time since 1820.

Background

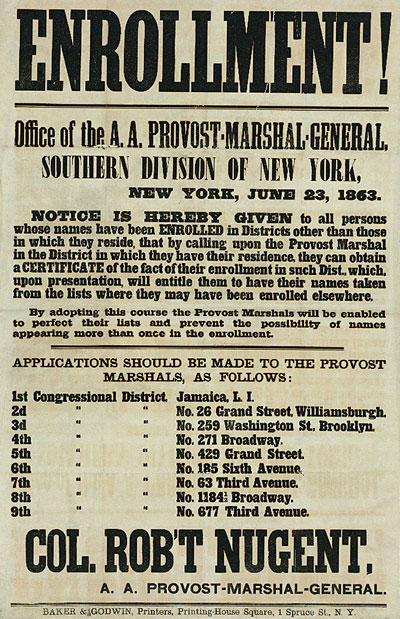

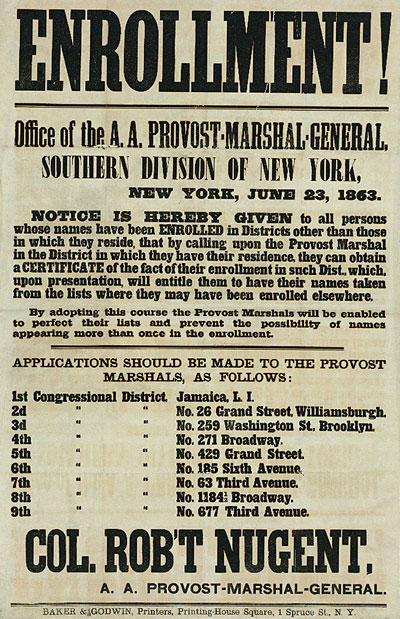

New York's economy was tied to the Southern United States, South; by 1822, nearly half of its exports were cotton shipments. In addition, upstate textile mills processed cotton in manufacturing. New York had such strong business connections to the South that on January 7, 1861, Mayor Fernando Wood, a Democrat, called on the city's New York City Council, Board of Aldermen to "declare the city's independence from Albany, New York, Albany and from Washington, D.C., Washington"; he said it "would have the whole and united support of the Southern States." When the Union (American Civil War), Union entered the war, New York City had many sympathizers with the South.''New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War Online Exhibit''New York Historical Society (November 17, 2006 to September 3, 2007, physical exhibit); accessed May 10, 2012. The city was also a continuing destination of immigrants. Since the 1840s, most were from Ireland and Germany. In 1860, nearly 25 percent of the New York City population was German-born, and many did not speak English. During the 1840s and 1850s, journalists had published sensational accounts, directed at the white working class, dramatizing the evils of interracial socializing, relationships, and marriages. Reformers joined the effort. Newspapers carried derogatory portrayals of black people and ridiculed "black aspirations for equal rights in voting, education, and employment". The Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party's Tammany Hall political machine had been working to enroll immigrants as U.S. citizens so they could vote in local elections and had strongly recruited Irish. In March 1863, with the war continuing, Congress passed the Enrollment Act to establish a draft for the first time, as more troops were needed. In New York City and other locations, new citizens learned they were expected to register for the draft to fight for their new country. Black men were excluded from the draft as they were largely not considered citizens, and wealthier white men could pay for substitutes. New York political offices, including the mayor, were historically held by Democrats before the war, but the election of Abraham Lincoln as president had demonstrated the rise in Republican political power nationally. Newly elected New York City Republican Mayor George Opdyke was mired in profiteering scandals in the months leading up to the riots. The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1863 alarmed much of the white working class in New York, who feared that freed slaves would migrate to the city and add further competition to the labor market. There had already been tensions between black and white workers since the 1850s, particularly at the docks, with free blacks and immigrants competing for low-wage jobs in the city. In March 1863, white Stevedore, longshoremen refused to work with black laborers and rioted, attacking 200 black men.

Riots

Monday

There were reports of rioting in Buffalo, New York, and certain other cities, but the first drawing of draft numbers—on July 11, 1863—occurred peaceably in Manhattan. The second drawing was held on Monday, July 13, 1863, ten days after the Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg. At 10 a.m., a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the "Black Joke"), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place.

The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, burst through the doors, and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses that were pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut Telegraphy, telegraph lines.

Since the New York Guard, New York State Militia had been sent to assist Union troops at Gettysburg campaign, Gettysburg, the local New York City Police Department, New York Metropolitan Police Department was the only force on hand to try to suppress the riots. Police Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy, John Kennedy arrived at the site on Monday to check on the situation. Although he was not in uniform, people in the mob recognized him and attacked him. Kennedy was left nearly unconscious, his face bruised and cut, his eye injured, his lips swollen, and his hand cut with a knife. He had been beaten to a mass of bruises and blood all over his body.

Police drew their Club (weapon), clubs and revolvers and charged the crowd but were overpowered. The police were badly outnumbered and unable to quell the riots, but they kept the rioting out of Lower Manhattan below Union Square (New York City), Union Square. Inhabitants of the "Bloody Sixth" Ward, around the South Street Seaport and Five Points (Manhattan), Five Points areas, refrained from involvement in the rioting. The 19th Company/1st Battalion US Army Invalid Corps which was part of the Provost Guard tried to disperse the mob with a volley of gunfire but were overwhelmed and suffered over 14 injured with 1 soldier missing (believed killed).

There were reports of rioting in Buffalo, New York, and certain other cities, but the first drawing of draft numbers—on July 11, 1863—occurred peaceably in Manhattan. The second drawing was held on Monday, July 13, 1863, ten days after the Union victory at Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg. At 10 a.m., a furious crowd of around 500, led by the volunteer firemen of Engine Company 33 (known as the "Black Joke"), attacked the assistant Ninth District provost marshal's office, at Third Avenue and 47th Street, where the draft was taking place.

The crowd threw large paving stones through windows, burst through the doors, and set the building ablaze. When the fire department responded, rioters broke up their vehicles. Others killed horses that were pulling streetcars and smashed the cars. To prevent other parts of the city being notified of the riot, they cut Telegraphy, telegraph lines.

Since the New York Guard, New York State Militia had been sent to assist Union troops at Gettysburg campaign, Gettysburg, the local New York City Police Department, New York Metropolitan Police Department was the only force on hand to try to suppress the riots. Police Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy, John Kennedy arrived at the site on Monday to check on the situation. Although he was not in uniform, people in the mob recognized him and attacked him. Kennedy was left nearly unconscious, his face bruised and cut, his eye injured, his lips swollen, and his hand cut with a knife. He had been beaten to a mass of bruises and blood all over his body.

Police drew their Club (weapon), clubs and revolvers and charged the crowd but were overpowered. The police were badly outnumbered and unable to quell the riots, but they kept the rioting out of Lower Manhattan below Union Square (New York City), Union Square. Inhabitants of the "Bloody Sixth" Ward, around the South Street Seaport and Five Points (Manhattan), Five Points areas, refrained from involvement in the rioting. The 19th Company/1st Battalion US Army Invalid Corps which was part of the Provost Guard tried to disperse the mob with a volley of gunfire but were overwhelmed and suffered over 14 injured with 1 soldier missing (believed killed).

The Bull's Head hotel on 44th Street, which refused to provide alcohol to the rioters, was burned. The mayor's residence on Fifth Avenue was spared by words of Judge George G. Barnard, George Gardner Barnard, and the crowd of about 500 turned to another location of pillage. The Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. Other targets included the office of the ''New York Times''. The mob was turned back at the ''Times'' office by staff manning Gatling guns, including ''Times'' founder Henry Jarvis Raymond. Fire engine companies responded, but some firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters because they had also been drafted on Saturday. The ''New-York Tribune, New York Tribune'' was attacked, being looted and burned; not until police arrived and extinguished the flames, dispersing the crowd. Later in the afternoon, authorities shot and killed a man as a crowd attacked the armory at Second Avenue (Manhattan), Second Avenue and 21st Street. The mob broke all the windows with paving stones ripped from the street. The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black civilians, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then Lynching, lynched, hanged from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum at 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue, a "symbol of white charity to blacks and of black upward mobility" that provided shelter for 233 children, was attacked by a mob at around 4 p.m. A mob of several thousand, including many women and children, looted the building of its food and supplies. However, the police were able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow the orphans to escape before the building burned down. Throughout the areas of rioting, mobs attacked and killed numerous black civilians and destroyed their known homes and businesses, such as James McCune Smith's pharmacy at 93 West Broadway, believed to be the first owned by a black man in the United States.

Near the midtown docks, tensions brewing since the mid-1850s boiled over. As recently as March 1863, white employers had hired black longshoremen, with whom many White men refused to work. Rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers" to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from the area near the docks. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to black people. Mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

The Bull's Head hotel on 44th Street, which refused to provide alcohol to the rioters, was burned. The mayor's residence on Fifth Avenue was spared by words of Judge George G. Barnard, George Gardner Barnard, and the crowd of about 500 turned to another location of pillage. The Eighth and Fifth District police stations, and other buildings were attacked and set on fire. Other targets included the office of the ''New York Times''. The mob was turned back at the ''Times'' office by staff manning Gatling guns, including ''Times'' founder Henry Jarvis Raymond. Fire engine companies responded, but some firefighters were sympathetic to the rioters because they had also been drafted on Saturday. The ''New-York Tribune, New York Tribune'' was attacked, being looted and burned; not until police arrived and extinguished the flames, dispersing the crowd. Later in the afternoon, authorities shot and killed a man as a crowd attacked the armory at Second Avenue (Manhattan), Second Avenue and 21st Street. The mob broke all the windows with paving stones ripped from the street. The mob beat, tortured and/or killed numerous black civilians, including one man who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then Lynching, lynched, hanged from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum at 43rd Street and Fifth Avenue, a "symbol of white charity to blacks and of black upward mobility" that provided shelter for 233 children, was attacked by a mob at around 4 p.m. A mob of several thousand, including many women and children, looted the building of its food and supplies. However, the police were able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow the orphans to escape before the building burned down. Throughout the areas of rioting, mobs attacked and killed numerous black civilians and destroyed their known homes and businesses, such as James McCune Smith's pharmacy at 93 West Broadway, believed to be the first owned by a black man in the United States.

Near the midtown docks, tensions brewing since the mid-1850s boiled over. As recently as March 1863, white employers had hired black longshoremen, with whom many White men refused to work. Rioters went into the streets in search of "all the negro porters, cartmen and laborers" to attempt to remove all evidence of a black and interracial social life from the area near the docks. White dockworkers attacked and destroyed brothels, dance halls, boarding houses, and tenements that catered to black people. Mobs stripped the clothing off the white owners of these businesses.

Tuesday

Heavy rain fell on Monday night, helping to abate the fires and sending rioters home, but the crowds returned the next day. Rioters burned down the home of Abigail Hopper Gibbons, Abby Gibbons, a prison reformer and the daughter of abolitionist Isaac Hopper. They also attacked white "Amalgamation (race), amalgamationists", such as Ann Derrickson and Ann Martin, two white women who were married to black men, and Mary Burke, a white prostitute who catered to black men. Governor Horatio Seymour arrived on Tuesday and spoke at New York City Hall, City Hall, where he attempted to assuage the crowd by proclaiming that the Conscription Act was unconstitutional. General John E. Wool, commander of the Eastern District, brought approximately 800 soldiers and Marines in from forts in New York Harbor, West Point, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He ordered the militias to return to New York.Wednesday

The situation improved July 15 when assistant provost-marshal-general Robert Nugent (officer), Robert Nugent received word from his superior officer, Colonel James Barnet Fry, to postpone the draft. As this news appeared in newspapers, some rioters stayed home. But some of the militias began to return and used harsh measures against the remaining rioters. The rioting spread to Brooklyn and Staten Island.Thursday

Order began to be restored on July 16. The New York State Militia and some federal troops were returned to New York, including the 152nd New York Volunteer Infantry, 152nd New York Volunteers, the 26th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment, 26th Michigan Volunteers, the 27th Regiment Indiana Infantry, 27th Indiana Volunteers and the 7th Regiment New York State Militia from Frederick, Maryland, after a forced march. In addition, the governor sent in the 74th and 65th regiments of the New York State Militia, which had not been in federal service, and a section of the 20th Independent Battery, New York Volunteer Artillery from Fort Schuyler in Throggs Neck. The New York State Militia units were the first to arrive. There were several thousand militia and Federal troops in the city. A final confrontation occurred in the evening near Gramercy Park. According to Adrian Cook, twelve people died on this last day of the riots in skirmishes between rioters, the police, and the Army. ''The New York Times'' reported on Thursday that Plug Uglies and Blood Tubs gang members from Baltimore, as well as "Scuykill Rangers [sic] and other rowdies of Philadelphia", had come to New York during the unrest to participate in the riots alongside the Dead Rabbits and "Mackerelvillers". The ''Times'' editorialized that "the scoundrels cannot afford to miss this golden opportunity of indulging their brutal natures, and at the same time serving their colleagues the Copperhead (politics), Copperheads and secesh [secessionist] sympathizers."Aftermath

The exact death toll during the New York draft riots is unknown, but according to historian James M. McPherson, 119 or 120 people were killed. Violence by longshoremen against black men was especially fierce in the docks area: In all, eleven black men were hanged over five days. Among the murdered blacks was the seven-year-old nephew of Bermuda, Bermudian First Sergeant Robert John Simmons of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, whose account of fighting in South Carolina, written on the approach to Fort Wagner July 18, 1863, was to be published in the ''New York Tribune'' on December 23, 1863 (Simmons having died in August of wounds received in the attack on Fort Wagner). The most reliable estimates indicate at least 2,000 people were injured. Herbert Asbury, the author of the 1928 book ''The Gangs of New York (book), Gangs of New York'', upon which Gangs of New York, the 2002 film was based, puts the figure much higher, at 2,000 killed and 8,000 wounded, a number that some dispute. Total property damage was about $1–5 million (equivalent to $ – $ in ). The city treasury later Indemnity, indemnified one-quarter of the amount. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that the riots were "equivalent to a Confederate victory". Fifty buildings, including two Protestant churches and the Colored Orphan Asylum, were burned to the ground. 4,000 federal troops had to be pulled out of the Gettysburg Campaign to suppress the riots, troops that could have aided in pursuing the battered Army of Northern Virginia as it retreated out of Union territory. During the riots, landlords, fearing that the mob would destroy their buildings, drove black residents from their homes. As a result of the violence against them, hundreds of black people left New York, including physician James McCune Smith and his family, moving to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, or New Jersey. The white elite in New York organized to provide relief to black riot victims, helping them find new work and homes. The Union League Club and the Committee of Merchants for the Relief of Colored People provided nearly $40,000 to 2,500 victims of the riots. By 1865 the black population in the city had dropped to under 10,000, the lowest since 1820. The white working-class riots had changed the demographics of the city, and white residents exerted their control in the workplace; they became "unequivocally divided" from the black population. On August 19, the government resumed the draft in New York. It was completed within 10 days without further incident. Fewer men were drafted than had been feared by the white working class: of the 750,000 selected nationwide for conscription, only about 45,000 were sent into active duty. While the rioting mainly involved the white working class, middle and upper-class New Yorkers had split sentiments on the draft and use of federal power or martial law to enforce it. Many wealthy Democratic Party (United States), Democratic businessmen sought to have the draft declared constitutionality, unconstitutional. Tammany Hall, Tammany Democrats did not seek to have the draft declared unconstitutional, but they helped pay the commutation fees for those who were drafted. In December 1863, the Union League Club recruited more than 2,000 black soldiers, outfitted and trained them, honoring and sending men off with a parade through the city to the Hudson River docks in March 1864. A crowd of 100,000 watched the procession, which was led by police and members of the Union League Club. New York's support for the Union cause continued, however grudgingly, and gradually Southern sympathies declined in the city. New York banks eventually financed the Civil War, and the state's industries were more productive than those of the entire Confederacy. By the end of the war, more than 450,000 soldiers, sailors, and militia had enlisted from New York State, which was the most populous state at the time. A total of 46,000 military men from New York State died during the war, more from disease than wounds, as was typical of most combatants.Order of battle

New York Metropolitan Police Department

New York City Police Department, New York Metropolitan Police Department under the command of Police superintendent, Superintendent John Alexander Kennedy, John A. Kennedy.New York City Police Commissioner#Commissioners, Commissioners Thomas Coxon Acton and John G. Bergen took command when Kennedy was seriously injured by a mob during the early stages of the riots.

Of the NYPD Officers-there were four fatalities-1 killed and 3 died of injuries

New York State Militia

1st Division: Major General Charles W. Sandford Unorganized Militia:Union Army

Department of the East: Major General John E. Wool headquartered in New York Defenses of New York City: Brevet (military), Brevet Brigadier general (United States), Brigadier General Harvey Brown (US Army officer), Harvey Brown, Brig. General Edward R. S. CanbyBrown was relieved of duty on July 16 and Canby succeeded him in command of the military post of New York City on July 17 * Artillery: Captain Henry F. Putnam, 12th United States Infantry Regiment. * Provost marshals tasked with overseeing the initial enforcement of the draft: ** Provost Marshal General United States Army, U.S.A.: Colonel James Barnet Fry, James Fry ** Provost Marshal General New York City: Colonel Robert Nugent (officer), Robert Nugent (During the first day of rioting on July 13, 1863, in command of the Invalid Corps: 1st Battalion) United States Secretary of War, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton authorized five regiments from Battle of Gettysburg, Gettysburg, mostly federalized state militia and volunteer units from the Army of the Potomac, to reinforce the New York City Police Department. By the end of the riots, there were more than 4,000 soldiers garrisoned in the troubled area.Fiction

* ''Wilderness: A Tale of the Civil War'' (1961) by Robert Penn Warren * ''The Banished Children of Eve, A Novel of Civil War New York'' (1995) by Peter Quinn (author), Peter Quinn * ''My Notorious Life: A Novel'' (2014) by Kate Manning * ''On Secret Service'' (2000) by John Jakes * ''Paradise Alley'' (2003) by Kevin Baker (author), Kevin Baker * ''New York: the Novel'' (2009) by Edward Rutherfurd * ''Grant Comes East'' (2004) by Newt Gingrich * ''Last Descendants'' (2016) by Matthew J. Kirby * ''Riot'' (2009) by Walter Dean Myers *''A Wish After Midnight'' (2008) by Zetta Elliott, speculative fiction set in Brooklyn alternating between the early 21st century and 1863. *''Libertie'' (2021) by Kaitlyn Greenidge * ''Moon and the Mars'' (2021) by Kia CorthronTelevision, theatre and film

* The short-lived 1968 Broadway theatre, Broadway musical theatre, musical ''Maggie Flynn'' was set in the Tobin Orphanage for black children (modeled on the Colored Orphan Asylum). * ''Gangs of New York'' (2002), a film directed by Martin Scorsese, includes a fictionalized portrayal of the New York Draft Riots. * ''Paradise Square (musical), Paradise Square'' (2018), a musical that had its Broadway debut in 2022, depicts events that led up to and included the New York Draft Riots. * Copper (2012), a television show about Five Points in New York City in 1864/1865, has flashbacks to the riots and the lynchings which took place in the area.See also

* Fishing Creek Confederacy * History of New York City (1855–1897) * List of ethnic riots#United States * List of expulsions of African Americans * List of identities in The Gangs of New York (book)#Draft riots, List of identities in ''The Gangs of New York'' § Draft riots * List of incidents of civil unrest in New York City * List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States * List of massacres in the United States * Lynching in the United States * Mass racial violence in the United States * Opposition to the American Civil War * Racism against Black Americans * Racism in the United StatesNotes

References

* * * * Joel Tyler Headley, Headley, Joel Tyler (1873)''The Great Riots of New York, 1712 to 1863'' – including and full and complete account of the Four Days' Draft Riot of 1863.

E.B. Treat (publisher), stereotyped at the Women's Printing House * * * * *

Further reading

* Anbinder, Tyler. "Which Poor Man’s Fight?: Immigrants and the Federal Conscription of 1863." ''Civil War History'' 52.4 (2006): 344–372. * Barrett, Ross. "On Forgetting: Thomas Nast, the Middle Class, and the Visual Culture of the Draft Riots." ''Prospects'' 29 (2005): 25–55online

* Cohen, Joanna (2022). "doi:10.1093/jahist/jaac118, Reckoning with the Riots: Property, Belongings, and the Challenge to Value in Civil War America". ''Journal of American History''. 109 (1): 68–98. * Geary, James W. "Civil War Conscription in the North: a historiographical review." ''Civil War History'' 32.3 (1986): 208–228. * Hauptman, Laurence M. "John E. Wool and the New York City draft riots of 1863: a reassessment." ''Civil War History'' 49.4 (2003): 370–387. * Joyce, Toby. "The New York draft riots of 1863: an Irish civil war?" ''History Ireland'' 11.2 (2003): 22–27

online

* Man Jr, Albon P. "Labor competition and the New York draft riots of 1863." ''Journal of Negro History'' 36.4 (1951): 375–405. On Black role

online

* Moss, Hilary. "All the World’s New York, All New York’sa Stage: Drama, Draft Riots, and Democracy in the Mid-Nineteenth Century" ''Journal of Urban History'' (2009) 35#7 pp. 1067–1072; DOI: 10.1177/0096144209347095 * Perri, Timothy J. “The Economics of US Civil War Conscription.” ''American Law and Economics Review'' 10#2 (2008), pp. 424–53

online

* Peterson, Carla L. "African Americans and the New York Draft Riots: Memory and Reconciliation in America’s Civil War." ''Nanzan review of American studies: a journal of Center for American Studies'' v27 (2005): 1–14

online

* Quigley, David. '' Second Founding: New York City, Reconstruction, and the Making of American Democracy'' (Hill and Wang, 2004

excerpt

* Quinn, Peter. 1995 ''Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York''. New York: Fordham University Press (fictional account of Draft Riots) * Rutkowski, Alice. "Gender, genre, race, and nation: The 1863 New York City draft riots." ''Studies in the Literary Imagination'' 40.2 (2007): 111+. * Walkowitz, Daniel J. "‘The Gangs of New York’: The mean streets in history." ''History Workshop Journal'' 56#1 (2003

online

* Wells, Jonathan Daniel. "Inventing White Supremacy: Race, Print Culture, and the Civil War Draft Riots." ''Civil War History'' 68.1 (2022): 42–80.

Primary sources

* Dupree, A. Hunter and Leslie H. Fishel, Jr. "An Eyewitness Account of the New York Draft Riots, July, 1863", ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' vol. 47, no. 3 (December 1960), pp. 472–79In JSTOR

* * ''New York Evangelist'' (1830–1902); July 23, 1863; pp. 30, 33; APS Online, pg. 4. *

online

External links

''Report of the Committee of merchants for the relief of colored people, suffering from the late riots in the city of New York''. New York: G. A. Whitehorne, 1863

African American Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress.

''New York Divided: Slavery and the Civil War Online Exhibit''

New York Historical Society, (November 17, 2006 – September 3, 2007, physical exhibit)

2002, source Civil War Society's ''Civil War Encyclopedia'', Civil War Home website

First Edition Harper's News Report, sonofthesouth.net

"1863 New York City Draft Riots"

mrlincolnandnewyork.org

Bill Bigelow, "The Draft Riot Mystery"

9-page lesson plan for High School Students, 2012, Zinn Education Project/Teaching for Change {{good article 1863 in New York (state) 1863 riots African Americans in the American Civil War Anti-war protests in the United States Conscription in the United States Irish-American history Massacres in the United States Military history of New York City Military history of New York (state) New York (state) in the American Civil War Political riots in the United States Racially motivated violence against African Americans Riots and civil disorder in New York City Riots and civil unrest during the American Civil War White American riots in the United States Protests in New York (state) Working class in the United States July 1863 events 1860s in New York City, Draft riots 19th century in Manhattan Mass murder in 1863 Riots and civil disorder in New York (state) 1863 murders in the United States Rebellions in the United States Working-class culture in New York City