Native American tribes in Virginia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the indigenous tribes who currently live or have historically lived in what is now the

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the indigenous tribes who currently live or have historically lived in what is now the

The first European explorers in what is now Virginia were

The first European explorers in what is now Virginia were

Another expression of the different cultures of the three major language groups were their practices in constructing dwellings, both in style and materials. The Monacan, who spoke a Siouan language, created dome-shaped structures covered with bark and reed mats.

The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy spoke

Another expression of the different cultures of the three major language groups were their practices in constructing dwellings, both in style and materials. The Monacan, who spoke a Siouan language, created dome-shaped structures covered with bark and reed mats.

The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy spoke

In April 1613, Captain

In April 1613, Captain  The 1646 treaty delineated a racial frontier between Indian and English settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by special pass obtained at one of the newly erected border forts. By this treaty, the extent of the Virginia Colony open to patent by English colonists was defined as:

The 1646 treaty delineated a racial frontier between Indian and English settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by special pass obtained at one of the newly erected border forts. By this treaty, the extent of the Virginia Colony open to patent by English colonists was defined as:

Among the early Crown Governors of Virginia, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood had one of the most coherent policies toward Native Americans during his term (1710–1722), and one that was relatively respectful of them. He envisioned having forts built along the frontier, which Tributary Nations would occupy, to act as buffers and go-betweens for trade with the tribes farther afield. They would also receive Christian instruction and civilization. The Virginia Indian Company was to hold a government monopoly on the thriving fur trade. The first such project, Fort Christanna, was a success in that the

Among the early Crown Governors of Virginia, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood had one of the most coherent policies toward Native Americans during his term (1710–1722), and one that was relatively respectful of them. He envisioned having forts built along the frontier, which Tributary Nations would occupy, to act as buffers and go-betweens for trade with the tribes farther afield. They would also receive Christian instruction and civilization. The Virginia Indian Company was to hold a government monopoly on the thriving fur trade. The first such project, Fort Christanna, was a success in that the

Virginia Council on Indians

''Washington Post'', 13 Jul 2006

Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2007

, Library of Congress

''Washington Post'', 25 Nov 2007 * ttp://www.vitalva.org/ Virginia Indian Tribal Alliance for Life

Virginia Pow-Wow Schedule

{{DEFAULTSORT:Native American Tribes In Virginia

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the indigenous tribes who currently live or have historically lived in what is now the

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the indigenous tribes who currently live or have historically lived in what is now the Commonwealth of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

in the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

.

All of the Commonwealth of Virginia used to be Virginia Indian territory. Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

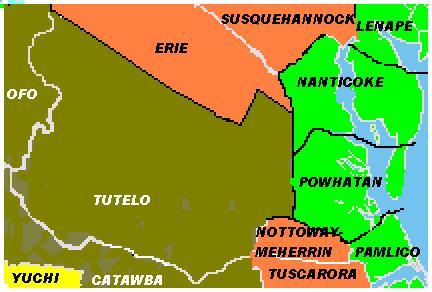

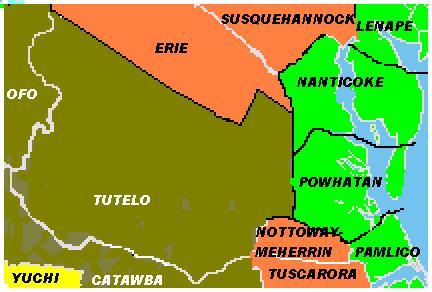

have occupied the region for at least 12,000 years. Their population has been estimated to have been about 50,000 at the time of European colonization. At contact, Virginian tribes belonged to tribes and spoke languages belonging to three major language families: roughly, Algonquian along the coast and Tidewater region, Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the ent ...

in the Piedmont region above the Fall Line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is typically prominent where rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the coa ...

, and Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoia ...

in the interior, particularly the mountains. About 30 Algonquian tribes were allied in the powerful Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

paramount chiefdom

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a chief-based system. This term is used occasionally in anthropological and arch ...

along the coast, which was estimated to include 15,000 people at the time of English colonization.

Few written documents assess the traditions and quality of life of some of the various early tribes that populated the Virginia region. One account lists the observations of an Englishman who encountered groups of Native peoples during his time in Virginia. The author notes the Virginia Natives' diet depended on cultivated corn, meat and fish from hunting, and gathered fruits. He noted they believed in an afterlife, and recorded differences in characteristics among Native nations based on region and the size of population.

Due to the early and extended history, by the post-Civil War period, most tribes had lost their lands and many had suffered decades of disruption and high mortality due to epidemics of infectious diseases. Because the Native Americans generally lacked reservations and some had intermarried with Europeans and African Americans, many colonists and later European-American residents of Virginia assumed that the Native Americans were disappearing. They did not understand that mixed-race descendants could be brought up as fully culturally Native American.

But many Native Americans maintained their cultures and became increasingly active in the late 20th century in asserting their identities. After struggling to gain recognition from the state and federal governments, six tribes gained Congressional support for recognition. As of January 29, 2018, Virginia has seven federally recognized tribe

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the Unite ...

s: the Pamunkey Indian Tribe

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments, ...

, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond

The Nansemond are the indigenous people of the Nansemond River, a 20-mile long tributary of the James River in Virginia. Nansemond people lived in settlements on both sides of the Nansemond River where they fished (with the name "Nansemond" mean ...

and Monacan. The latter six gained recognition through passage of federal legislation in the 21st century.

In addition, the Commonwealth of Virginia has recognized these seven and another four tribes, most since the late 20th century. Only two of the tribes, the Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments ...

and Mattaponi

The Mattaponi () tribe is one of only two Virginia Indian tribes in the Commonwealth of Virginia that owns reservation land, which it has held since the colonial era. The larger Mattaponi Indian Tribe lives in King William County on the reser ...

, have retained reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

lands assigned by 17th-century treaties made with the English colonists. In the late 20th century, state law established an official recognition process.

Federal legislation to provide recognition to six of Virginia's non-reservation tribes was developed and pushed over a period of 19 years. Hearings established that the tribes would have been able to meet the federal criteria for continuity and retention of identity as tribes, but they were disadvantaged by lacking reservations and, mostly, by racially discriminatory state governmental actions that altered records of Indian identification and continuity. In addition, some records were destroyed during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and earlier conflicts.

State officials arbitrarily changed vital records of birth and marriage while implementing the Racial Integrity Act of 1924; they removed identification of individuals as Indian and reclassified them as either white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ...

or non-white

The term "person of color" ( : people of color or persons of color; abbreviated POC) is primarily used to describe any person who is not considered "white". In its current meaning, the term originated in, and is primarily associated with, the U ...

(i.e. colored

''Colored'' (or ''coloured'') is a racial descriptor historically used in the United States during the Jim Crow Era to refer to an African American. In many places, it may be considered a slur, though it has taken on a special meaning in Sout ...

), according to the state's "one-drop rule

The one-drop rule is a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")Davis, F. James. Frontlin" ...

" (most members of Virginia tribes are multiracial

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-eth ...

, including European and/or African ancestry), without regard for how people identified. This resulted in Indian individuals and families losing the documentation of their ethnic identities. Since the late 20th century, many of the tribes who had maintained cultural continuity reorganized and began to press for federal recognition. In 2015 the Pamunkey completed their process and were officially recognized as an Indian tribe by the federal government.

Following nearly two decades of work, federal legislation to recognize the six tribes was passed by Congress and signed by President Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

on January 29, 2018.

History

16th century

The first European explorers in what is now Virginia were

The first European explorers in what is now Virginia were Spaniards

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both ...

, who landed at two separate places several decades before the English founded Jamestown in 1607. By 1525 the Spanish had charted the eastern Atlantic coastline north of Florida. In 1609, Francisco Fernández de Écija

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed "Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comunitatis'' (father of ...

, seeking to deny the English claim, asserted that Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón (c. 1480 – 18 October 1526) was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United State ...

's failed colony of San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) is a former Spanish colony in present-day Georgetown County, South Carolina, founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.In early 1521, Ponce de León had made a poorly documented, disas ...

, which lasted the three months of winter 1526–27, had been near Jamestown. Modern scholars instead place this first Spanish colony within US boundaries as having been on an island off Georgia.

In 1542, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

in his expedition to the North American continent encountered the Chisca

The Chisca were a tribe of Native Americans living in present-day eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia in the 16th century, and in present day Alabama, Georgia, and Florida in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, by which time th ...

people, who lived in present-day southwestern Virginia. In the spring of 1567, the conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, ...

Juan Pardo was based at Fort San Juan, built near the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

center of Joara

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles from the Atlantic coast in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joara is n ...

in present-day western North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

. He sent a detachment under Hernando Moyano de Morales into present-day Virginia. This expedition destroyed the Chisca village of Maniatique. The site was later was developed as the present-day town of Saltville, Virginia

Saltville is a town in Smyth and Washington counties in the U.S. state of Virginia. The population was 2,077 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Kingsport– Bristol (TN)– Bristol (VA) Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a compon ...

.

Meanwhile, as early as 1559–60, the Spanish had explored Virginia, which they called Ajacán, from the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

while they sought a water passage to the west. They captured a Native man, possibly from the Paspahegh or Kiskiack tribe, whom they named Don Luis after they baptize

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

d him. They took him to Spain, where he received a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

education. About ten years later, Don Luis returned with Spanish Jesuit missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

to establish the short-lived Ajacán Mission. Native Americans attacked it in 1571 and killed all the missionaries.

English attempts to settle the Roanoke Colony

The establishment of the Roanoke Colony ( ) was an attempt by Sir Walter Raleigh to found the first permanent English settlement in North America. The English, led by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, had briefly claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, in ...

in 1585–87 failed. Although the island site is located in present-day North Carolina, the English considered it part of the Virginia territory. The English collected ethnological information about the local Croatan tribe, as well as related coastal tribes extending as far north as the Chesapeake Bay.

There were no records of indigenous life before the Europeans started documenting their expeditions and colonization efforts. But scholars have used archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

, linguistic

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

and anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

research to learn more about the cultures and lives of Native Americans in the region. Contemporary historians have also learned how to use the Native American oral traditions to explore their history.

According to colonial historian William Strachey

William Strachey (4 April 1572 – buried 21 June 1621) was an English writer whose works are among the primary sources for the early history of the English colonisation of North America. He is best remembered today as the eye-witness reporter o ...

, Chief Powhatan had slain the ''weroance'' at Kecoughtan In the seventeenth century, Kecoughtan was the name of the settlement now known as Hampton, Virginia, In the early twentieth century, it was also the name of a town nearby in Elizabeth City County. It was annexed into the City of Newport News in 19 ...

in 1597, appointing his own young son Pochins as successor there. Powhatan resettled some of that tribe on the Piankatank River. (He annihilated the adult male inhabitants at Piankatank in fall 1608.)

In 1670 the German explorer John Lederer recorded a Monacan legend. According to their oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

, the Monacan, a Siouan-speaking people, settled in Virginia some 400 years earlier by following "an oracle," after being driven by enemies from the northwest. They found the Algonquian-speaking Tacci tribe (also known as Doeg) already living there. The Monacan told Lederer they had taught the Tacci to plant maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

. They said that before that innovation, the Doeg had hunted, fished, and gathered their food.

Another Monacan tradition holds that, centuries prior to European contact, the Monacan and the Powhatan tribes had been contesting part of the mountains in the western areas of today's Virginia. The Powhatan had pursued a band of Monacan as far as the Natural Bridge, where the Monacan ambushed the Powhatan on the narrow formation, routing them. The Natural Bridge became a sacred site to the Monacan known as the ''Bridge of Mahomny'' or ''Mohomny'' (Creator). The Powhatan withdrew their settlements to below the Fall Line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is typically prominent where rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the coa ...

of the Piedmont, far to the east along the coast.

Another tradition relates that the Doeg had once lived in the territory of modern King George County, Virginia

King George County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population sits at 26,723. Its county seat is the town of King George.

The county's largest employer is the U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Cente ...

. About 50 years before the English arrived at Jamestown (i.e. c. 1557), the Doeg split into three sections, with one part moving to what became organized as colonial Caroline County, one part moving to Prince William, and a third part remaining in King George.

Houses

Algonquian languages

The Algonquian languages ( or ; also Algonkian) are a subfamily of indigenous American languages that include most languages in the Algic language family. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from the orthographically simi ...

, as did many of the Atlantic coastal peoples all the way up into Canada. They lived in houses they called ''yihakans/yehakins,'' and which the English described as "longhouses". They were made from bent saplings lashed together at the top to make a barrel shape. The saplings were covered with woven mats or bark. The 17th-century historian William Strachey

William Strachey (4 April 1572 – buried 21 June 1621) was an English writer whose works are among the primary sources for the early history of the English colonisation of North America. He is best remembered today as the eye-witness reporter o ...

thought since bark was harder to acquire, families of higher status likely owned the bark-covered houses. In summer, when the heat and humidity increased, the people could roll up or remove the mat walls for better air circulation.

Inside a Powhatan house, bedsteads were built along both long walls. They were made of posts put in the ground, about a foot high or more, with small cross-poles attached. The framework was about wide, and was covered with reeds. One or more mats was placed on top for bedding, with more mats or skins for blankets. A rolled mat served as a pillow. During the day, the bedding was rolled up and stored so the space could be used for other purposes. There was little need for extra bedding because a fire was kept burning inside the houses to provide heat in the cold months. It would be used to repel insects during the warmer months.

Wildlife was abundant in this area. The buffalo were still plentiful in the Virginia Piedmont up until the 1700s. The Upper Potomac watershed (above Great Falls, Virginia

Great Falls is a census-designated place (CDP) in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. The population as of the 2010 census was 15,427, an increase of 80.5% from the 2000 census.

History

Colonial farm settlements began to form in the area a ...

) was once renowned for its unsurpassed abundance of wild geese, earning the Upper Potomac its former Algonquian name, ''Cohongoruton'' (Goose River). Men and boys hunted game, and harvested fish and shellfish. Women gathered greens, roots and nuts, and cooked these with the meats. Women were responsible for butchering the meat, gutting and preparing the fish, and cooking shellfish and vegetables for stew. In addition, women were largely responsible for the construction of new houses when the band moved for seasonal resources. Experienced women and older girls worked together to build the houses, with younger children assigned to assist.

17th century

In 1607, when the English made their first permanent settlement atJamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James (Powhatan) River about southwest of the center of modern Williamsburg. It was ...

, the area of the current state was occupied by numerous tribes of Algonquian, Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the ent ...

, and Iroquoian

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoia ...

linguistic stock. Captain John Smith made contact with numerous tribes, including the Wicocomico. More than 30 Algonquian tribes were associated with the politically powerful Powhatan Confederacy

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhata ...

(alternately Powhatan Chiefdom), whose homeland occupied much of the area east of the Fall Line

A fall line (or fall zone) is the area where an upland region and a coastal plain meet and is typically prominent where rivers cross it, with resulting rapids or waterfalls. The uplands are relatively hard crystalline basement rock, and the coa ...

along the coast. It spanned 100 by , and covered most of the tidewater Virginia area and parts of the Eastern Shore, an area they called ''Tsenacommacah

Tsenacommacah (pronounced in English; "densely inhabited land"; also written Tscenocomoco, Tsenacomoco, Tenakomakah, Attanoughkomouck, and Attan-Akamik) is the name given by the Powhatan people to their native homeland, the area encompassing all ...

''. Each of the more than 30 tribes of this confederacy had its own name and chief ('' weroance'' or ''werowance'', female ''weroansqua''). All paid tribute to a paramount chief (''mamanatowick'') or Powhatan

The Powhatan people (; also spelled Powatan) may refer to any of the indigenous Algonquian people that are traditionally from eastern Virginia. All of the Powhatan groups descend from the Powhatan Confederacy. In some instances, The Powhatan ...

, whose personal name was ''Wahunsenecawh''. Succession and property inheritance in the tribe was governed by a matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

kinship system and passed through the mother's line.

Below the fall line, related Algonquian groups, who were not tributary to Powhatan, included the Chickahominy and the Doeg in Northern Virginia

Northern Virginia, locally referred to as NOVA or NoVA, comprises several counties and independent cities in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is a widespread region radiating westward and southward from Washington, D.C. Wit ...

. The Chickahomony were independent of the Powhatan. Powhatan's chiefdom was a confederacy that relied on the cooperation and willingness of other Algonquian groups. The Chickahominy insisted on governing themselves and on having equal footing with the Powhatan. If Powhatan wished to use them as warriors, he had to hire them and pay them in copper.https://pstcc-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1qcuk90/TN_gale_ofa306597312 The Accawmacke

The Accomac people were a historic Native American tribe in Accomack and Northampton counties in Virginia.Frederick Webb Hodge, ''Handbook'', 8. They were loosely affiliated with the Powhatan Confederacy.

The term Accomac was eventually applie ...

(including the Gingaskin) of the Eastern Shore, and the Patawomeck

Patawomeck is a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identifies ...

of Northern Virginia, were fringe members of the Confederacy. As they were separated by water from Powhatan's domains, the Accawmacke enjoyed some measure of semi-autonomy under their own paramount chief, ''Debedeavon

Debedeavon (died 1657) was the chief ruler of the Accawmack people who lived on the Eastern Shore of Virginia upon the first arrival of English colonists in 1608. His title was recorded as "Ye Emperor of Ye Easterne Shore and King of Ye Great Nuss ...

,'' aka "The Laughing King".

The Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

and area above the fall line were occupied by Siouan-speaking groups, such as the Monacan and Manahoac. The Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Nottoway and Meherrin

The Meherrin Nation ( autonym: Kauwets'a:ka, "People of the Water") is one of seven state-recognized nations of Native Americans in North Carolina. They reside in rural northeastern North Carolina, near the river of the same name on the Virgini ...

lived in what is now Southside Virginia

Southside, or Southside Virginia, has traditionally referred to the portion of the state south of the James River, the geographic feature from which the term derives its name. This was the first area to be developed in the colonial period.

Duri ...

south of the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

. Other tribes occupied mountain and foothill areas. The region beyond the Blue Ridge (including West Virginia) was considered part of the sacred hunting grounds. Like much of the Ohio Valley, it was depopulated during the later Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

(1670–1700) by attacks from the powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois from New York and Pennsylvania.

French Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

maps prior to that were labeled showing that previous inhabitants included the Siouan "Oniasont" (Nahyssan) and the Tutelo

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a Siouan dialect of the Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of thei ...

or "Totteroy," the former name of Big Sandy River — and another name for the ''Yesan'' or ''Nahyssan''. (Similarly, the Kentucky River

The Kentucky River is a tributary of the Ohio River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 13, 2011 in the U.S. Commonwealth of Kentucky. The river and its t ...

in Kentucky was said to be anciently known as the Cuttawah, i.e., "Catawba" River. The Kanawha River

The Kanawha River ( ) is a tributary of the Ohio River, approximately 97 mi (156 km) long, in the U.S. state of West Virginia. The largest inland waterway in West Virginia, its valley has been a significant industrial region of the st ...

is believed to have been named centuries earlier to indicate a former homeland of the Conoy aka Piscataway.)

When the English first established the Virginia Colony

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertGilbert (Saunders Family), Sir Humphrey" (histor ...

, the Powhatan tribes had a combined population of about 15,000. Relations between the two peoples were not always friendly. After Captain John Smith

John Smith (baptized 6 January 1580 – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, Admiral of New England, and author. He played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first pe ...

was captured in the winter of 1607 and met with Chief Powhatan, relations were fairly good. The Powhatan sealed relationships such as trading agreements and alliances via the kinship between groups involved. The kinship was formed through a connection to a female member of the group. Powhatan sent food to the English, and was instrumental in helping the newcomers survive the early years.

By the time Smith left Virginia in the fall of 1609, due to a gunpowder accident, relations between the two peoples had begun to sour. In the absence of Smith, Native affairs fell to the leadership of Captain George Percy. The English and Powhatan's men led attacks on one another in near succession under Percy's time as negotiator. With both sides raiding in attempts to sabotage supplies and steal resources, English and Powhatan relations quickly fell apart. Their competition for land and resources led to the First Anglo-Powhatan War.

In April 1613, Captain

In April 1613, Captain Samuel Argall

Sir Samuel Argall (1572 or 1580 – 24 January 1626) was an English adventurer and naval officer.

As a sea captain, in 1609, Argall was the first to determine a shorter northern route from England across the Atlantic Ocean to the new English c ...

learned that Powhatan's "favorite" daughter Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of ...

was residing in a Patawomeck

Patawomeck is a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identifies ...

village. Argall abducted her to force Powhatan to return English prisoners and stolen agricultural tools and weapons. Negotiations between the two peoples began. It was not until after Pocahontas converted to Christianity and married Englishman John Rolfe

John Rolfe (1585 – March 1622) was one of the early English settlers of North America. He is credited with the first successful cultivation of tobacco as an export crop in the Colony of Virginia in 1611.

Biography

John Rolfe is believed ...

in 1614 that peace was reached between the two peoples. As noted, matrilineal kinship was stressed in Powhatan society. Pocahontas' marriage to John Rolfe linked the two peoples.

The peace continued until after Pocahontas died in England in 1617 and her father in 1618.

After Powhatan's death, the chiefdom passed to his brother Opitchapan. His succession was brief and the chiefdom passed to '' Opechancanough''. It was Opecancanough who planned a coordinated attack on the English settlements, beginning on March 22, 1622. He wanted to punish English encroachments on Indian lands and hoped to run the colonists off entirely. His warriors killed about 350-400 settlers (up to one-third of the estimated total population of about 1,200), during the attack. The colonists called it the Indian massacre of 1622

The Indian massacre of 1622, popularly known as the Jamestown massacre, took place in the English Colony of Virginia, in what is now the United States, on 22 March 1622. John Smith, though he had not been in Virginia since 1609 and was not an e ...

. Jamestown was spared because Chanco

Chanco is a name traditionally assigned to a Native American who is said to have warned a Jamestown colonist, Richard Pace, about an impending Powhatan attack in 1622. This article discusses how the Native American came to be known as Chanco.

...

, an Indian boy living with the English, warned the English about the impending attack. The English retaliated. Conflicts between the peoples continued for the next 10 years, until a tenuous peace was reached.

In 1644, ''Opechancanough'' planned a second attack to turn the English out. Their population had reached about 8,000. His warriors again killed about 350-400 settlers in the attack. It led to the Second Anglo-Powhatan War. In 1646, ''Opechancanough'' was captured by the English. Against orders, a guard shot him in the back and killed him. His death began the death of the Powhatan Confederacy. Opechancanough's successor, Necotowance signed his people's first treaty with the English in October 1646.

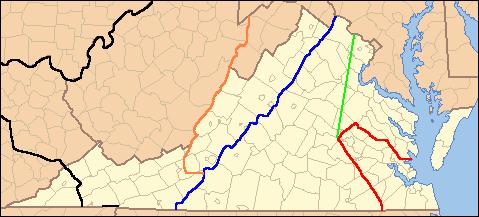

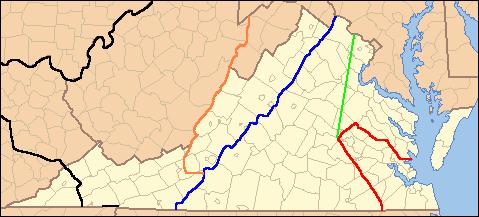

The 1646 treaty delineated a racial frontier between Indian and English settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by special pass obtained at one of the newly erected border forts. By this treaty, the extent of the Virginia Colony open to patent by English colonists was defined as:

The 1646 treaty delineated a racial frontier between Indian and English settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by special pass obtained at one of the newly erected border forts. By this treaty, the extent of the Virginia Colony open to patent by English colonists was defined as:

All the land between the Blackwater andIn 1658, English authorities became concerned that settlers would dispossess the tribes living near growing plantations and convened an assembly. The assembly stated English colonists could not settle on Indian land without permission from the governor, council, or commissioners and land sales had to be conducted in quarter courts, where they would be public record. Through this formal process, the Wicocomico transferred their lands in Northumberland County to Governor Samuel Mathews in 1659. Necotowance thus ceded the English vast tracts of uncolonized land, much of it between the James and Blackwater Rivers. The treaty required the Powhatan to make yearly tribute payment to the English of fish and game, and it also set up reservation lands for the Indians. All Indians were at first required to display a badge made of striped cloth while in white territory, or they could be murdered on the spot. In 1662, this law was changed to require them to display a copper badge, or else be subject to arrest. Around the year 1670, Seneca warriors from the New YorkYork York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...rivers, and up to the navigable point of each of the major rivers - which were connected by a straight line running directly from modern Franklin on the Blackwater, northwesterly to the Appomattoc village beside Fort Henry, and continuing in the same direction to the Monocan village above the falls of the James, where Fort Charles was built, then turning sharp right, to Fort Royal on the York (Pamunkey) river.

Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

conquered the territory of the Manahoac of Northern Piedmont. That year the Virginia Colony had expelled the Doeg from Northern Virginia east of the fall line. With the Seneca action, the Virginia Colony became ''de facto'' neighbours of part of the Iroquois Five Nations. Although the Iroquois never settled the Piedmont area, they entered it for hunting and raiding against other tribes. The first treaties conducted at Albany between the two powers in 1674 and 1684 formally recognized the Iroquois claim to Virginia above the Fall Line, which they had conquered from the Siouan peoples. At the same time, from 1671 to 1685, the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, th ...

seized what are now the westernmost regions of Virginia from the Xualae.

In 1677, following Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon against Colonial Governor William Berkeley, after Berkeley refused Bacon's request to drive Native American ...

, the Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed, with more of the Virginia tribes participating. The treaty reinforced the yearly tribute payments, and a 1680 annexe added the Siouan and Iroquoian tribes of Virginia to the roster of Tributary Indians. It allowed for more reservation lands to be set up. The treaty was intended to assert that the Virginia Indian leaders were subjects of the King of England.

In 1693 the College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William ...

officially opened. One of the initial goals of the college was to educate Virginia Indian boys. Funding from a farm named " Brafferton," in England, were sent to the school in 1691 for this purpose. The funds paid for living expenses, classroom space, and a teacher's pay. Only children of treaty tribes could attend, but at first none of them sent their children to the colonial school. By 1711, Governor Spotswood offered to remit the tribes' yearly tribute payments if they would send their boys to the school. The incentive worked and that year, the tribes sent twenty boys to the school. As the years passed, the number of Brafferton students decreased. By late in the 18th century, the Brafferton Fund was diverted elsewhere. From that time, the college was restricted to ethnic Europeans (or whites) until 1964, when the federal government passed civil rights legislation ending segregation in public facilities.

18th century

Among the early Crown Governors of Virginia, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood had one of the most coherent policies toward Native Americans during his term (1710–1722), and one that was relatively respectful of them. He envisioned having forts built along the frontier, which Tributary Nations would occupy, to act as buffers and go-betweens for trade with the tribes farther afield. They would also receive Christian instruction and civilization. The Virginia Indian Company was to hold a government monopoly on the thriving fur trade. The first such project, Fort Christanna, was a success in that the

Among the early Crown Governors of Virginia, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood had one of the most coherent policies toward Native Americans during his term (1710–1722), and one that was relatively respectful of them. He envisioned having forts built along the frontier, which Tributary Nations would occupy, to act as buffers and go-betweens for trade with the tribes farther afield. They would also receive Christian instruction and civilization. The Virginia Indian Company was to hold a government monopoly on the thriving fur trade. The first such project, Fort Christanna, was a success in that the Tutelo

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a Siouan dialect of the Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of thei ...

and Saponi

The Saponi or Sappony are a Native American tribe historically based in the Piedmont of North Carolina and Virginia.Raymond D. DeMaillie, "Tutelo and Neighboring Groups," pages 286–87. They spoke a Siouan language, related to the languages of ...

tribes took up residence. But, private traders, resentful of losing their lucrative share, lobbied for change, leading to its break-up and privatization by 1718.

Spotswood worked to make peace with his Iroquois neighbours, winning a concession from them in 1718, of all the land they had conquered as far as the Blue Ridge Mountains and south of the Potomac. This was confirmed at Albany in 1721. This clause was to be a bone of contention decades later, as it seemed to make the Blue Ridge the new demarcation between the Virginia Colony and Iroquois land. But the treaty technically stated that this mountain range was the border between the Iroquois and the Virginia Colony's ''Tributary Indians.'' White colonists considered this license to cross the mountains with impunity, which the Iroquois resisted. This dispute, which first flared in 1736 as Europeans began to settle the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

, came to a head in 1743. It was resolved the next year by the Treaty of Lancaster, settled in Pennsylvania.

Following this treaty, some dispute remained as to whether the Iroquois had ceded only the Shenandoah Valley, or all their claims south of the Ohio. Moreover, much of this land beyond the Alleghenies was disputed by claims of the Shawnee and Cherokee nations. The Iroquois recognized the English right to settle south of the Ohio at Logstown

"extensive flats"

, settlement_type = Historic Native American village

, image_skyline = Image:Logstown1.jpg

, imagesize = 220px

, image_alt =

, image_map1 = Pennsylvania in United States ...

in 1752. The Shawnee and Cherokee claims remained, however.

In 1755 the Shawnee, then allied with the French in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

, raided an English camp of settlers at Draper's Meadow, now Blacksburg, killing five and abducting five. The colonists called it the Draper's Meadow Massacre

In July 1755, the Draper's Meadow settlement in southwest Virginia, at the site of present day Blacksburg, was raided by a group of Shawnee warriors, who killed at least four people including an infant, and captured five more. The Indians brou ...

. The Shawnee captured Fort Seybert (now in West Virginia) in April 1758. Peace was reached that October with the Treaty of Easton, where the colonists agreed to establish no further settlements beyond the Alleghenies.

Hostilities resumed in 1763 with Pontiac's War

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–17 ...

, when Shawnee attacks forced colonists to abandon frontier settlements along the Jackson River, as well as the Greenbrier River

The Greenbrier River is a tributary of the New River, long,McNeel, William P. "Greenbrier River." ''The West Virginia Encyclopedia''. Ken Sullivan, editor. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Humanities Council. 2006. . in southeastern West Virgin ...

now in West Virginia, the associated valleys on either side of the Allegheny ridge, and the latter just beyond the Treaty of Easton limit. Meanwhile, the Crown's Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Proclam ...

confirmed all land beyond the Alleghenies as Indian Territory. It attempted to set up a reserve recognizing native control of this area and excluding European colonists. Shawnee attacks as far east as Shenandoah County

Shenandoah County (formerly Dunmore County) is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 44,186. Its county seat is Woodstock. It is part of the Shenandoah Valley region of Virgin ...

continued for the duration of Pontiac's War, until 1766.

Many colonists considered the Proclamation Line adjusted in 1768 by the Treaty of Hard Labour

In an effort to resolve concerns of settlers and land speculators following the western boundary established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 by George III of the United Kingdom, King George III, it was desired to move the boundary farther west to ...

, which demarcated a border with the Cherokee nation running across southwestern Virginia, and by the Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William ...

, by which the Iroquois Six Nations formally sold the British all their claim west of the Alleghenies, and south of the Ohio. However, this region (which included the modern states of Kentucky, and West Virginia, as well as southwestern Virginia) was still populated by the other tribes, including the Cherokee, Shawnee, Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory inclu ...

, and Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

, who were not party to the sale. The Cherokee border had to be readjusted in 1770 at the Treaty of Lochaber, because European settlement in Southwest Virginia had already moved past the 1768 Hard Labour line. The following year the Native Americans were forced to make further land concessions, extending into Kentucky. Meanwhile, the Virginian settlements south of the Ohio (in West Virginia) were bitterly challenged, particularly by the Shawnee.

The resulting conflict led to Dunmore's War (1774). A series of forts controlled by Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

began to be built in the valley of the Clinch River during this time. By the Treaty of Camp Charlotte concluding this conflict, the Shawnee and Mingo relinquished their claim south of the Ohio. The Cherokee sold Richard Henderson a portion of their land encompassing extreme southwest Virginia in 1775 as part of the Transylvania purchase. This sale was not recognized by the royal colonial government, nor by the Chickamauga Cherokee

The Chickamauga Cherokee refers to a group that separated from the greater body of the Cherokee during the American Revolutionary War. The majority of the Cherokee people wished to make peace with the Americans near the end of 1776, following se ...

war chief Dragging Canoe. But, contributing to the Revolution, settlers soon began entering Kentucky by rafting down the Ohio River in defiance of the Crown. In 1776, the Shawnee joined Dragging Canoe's Cherokee faction in declaring war on the " Long Knives" (Virginians). The chief led his Cherokee in a raid on Black's Fort on the Holston River

The Holston River is a river that flows from Kingsport, Tennessee, to Knoxville, Tennessee. Along with its three major forks (North Fork, Middle Fork and South Fork), it comprises a major river system that drains much of northeastern Tennessee, ...

(now Abingdon, Virginia) on July 22, 1776 (see Cherokee–American wars (1776–94)). Another Chickamauga leader, Bob Benge, also continued to lead raids in the westernmost counties of Virginia during these wars, until he was slain in 1794.

In August 1780, having lost ground to the British army in South Carolina fighting, the Catawba Nation

The Catawba, also known as Issa, Essa or Iswä but most commonly ''Iswa'' (Catawba: '' Ye Iswąˀ'' – "people of the river"), are a federally recognized tribe of Native Americans, known as the Catawba Indian Nation. Their current lands ar ...

fled their reservation and took temporary refuge in an unknown hiding spot in Virginia. They may have occupied the mountainous region around Catawba, Virginia in Roanoke County, which had not been settled by European Americans. They remained there in safety around nine months, until American general Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependab ...

led them to South Carolina, after the British were pushed out of that region near the end of the Revolution.

In the summer of 1786, after the United States had gained independence from Great Britain, a Cherokee hunting party fought a pitched two-day battle with a Shawnee one at the headwaters of the Clinch in present-day Wise County, Virginia

Wise County is a county located in the U.S. state of Virginia. The county was formed in 1856 from Lee, Scott, and Russell Counties and named for Henry A. Wise, who was the Governor of Virginia at the time.

History

The Cherokee conquered the ...

. It was a victory for the Cherokee although losses were heavy on both sides. This was the last battle between these tribes within the present limits of Virginia.

Throughout the 18th century, several tribes in Virginia lost their reservation lands. Shortly after 1700, the Rappahannock tribe lost its reservation; the Chickahominy tribe lost theirs in 1718, and the Nansemond tribe sold theirs in 1792 after the American Revolution. After losing their reservations, these tribes faded from the public record. Some of their landless members intermarried with other ethnic groups and became assimilated. Others maintained ethnic and cultural identification despite intermarriage. In their matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that ...

systems, children of Indian mothers were considered born into her clan and family, and Indian regardless of their fathers. By the 1790s, most of the surviving Powhatan tribes had converted to Christianity, and spoke only English.

19th century

During this period, ethnic Europeans continued to push the Virginia Indians off the remaining reservations and end their status as tribes. By 1850, one of the reservations was sold to the whites, and another reservation was officially divided by 1878. Many Virginia Indian families held onto their individual lands into the 20th century. The only two tribes to resist the pressure and hold onto their communal reservations were the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes. These two tribes still maintain their reservations today. After the Civil War, the reservation tribes began to reclaim their cultural identities. They asserted their identity in the Commonwealth of Virginia. They wanted to demonstrate that the Powhatan Indian descendants had maintained their cultural identity and were proud of their heritage. This was particularly important after the emancipation of slaves. The colonists and many white Virginians assumed that the many Indians of mixed race were no longer culturally Indian. But, they absorbed people of other ethnicities; especially if the mother was Indian, the children were considered to be members of her clan and tribe.20th century

In the early 20th century, many Virginia Indians began to reorganize into official tribes. They were opposed by Walter Ashby Plecker, the head of the Bureau of Vital Statistics in Virginia (1912–1946). Plecker was awhite supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

and a follower of the eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

movement, which had racial theories related to mistaken ideas about the superiority of the white race. Given the history of Virginia as a slave society, he wanted to keep the white "master race" "pure." In 1924 Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as " white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Cauc ...

(see below), establishing the one drop rule in law, by which individuals having any known African ancestry were to be considered African, or black.

Because of intermarriage and the long history of Virginia Indians not having communal land, Plecker believed there were few "true" Virginia Indians left. According to his beliefs, Indians of mixed race did not qualify, as he did not understand that Indians had a long practice of intermarriage and absorbing other peoples into their cultures. Their children may have been of mixed race but they identified as Indian.Fiske, Warren. "The Black-and-White World of Walter Ashby Plecker", ''The Virginian-Pilot'', 18 Aug 2004 The U.S. Department of the Interior accepted some of these "non Indians" as representing all of them when persuading them to cede lands.

The 1924 law institutionalized the "one-drop rule

The one-drop rule is a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")Davis, F. James. Frontlin" ...

", defining as black an individual with any known black/African ancestry. According to the Pocahontas Clause

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "Definitions of whiteness in the United States, white" a person "who has no tra ...

, a white person in Virginia could have a maximum blood quantum

Blood quantum laws or Indian blood laws are laws in the United States that define Native American status by fractions of Native American ancestry. These laws were enacted by the federal government and state governments as a way to estab ...

of one-sixteenth Indian ancestry without losing his or her legal status as white. This was a much more stringent definition than had prevailed legally in the state during the 18th and 19th centuries. Before the Civil War, a person could legally qualify as white who had up to one-quarter (equivalent to one grandparent) African or Indian ancestry. In addition, many court cases dealing with racial identity in the antebellum period were decided on the basis of community acceptance, which usually followed how a person looked and acted, and whether they fulfilled community obligations, rather than analysis of ancestry, which most people did not know in detail anyway.

A holdover from the slavery years and Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sou ...

, which still prevailed in the racially segregated state, the act prohibited marriage between whites and non-whites. It recognized only the terms of "white" and "colored" (which was related to ethnic African ancestry). Plecker was a strong proponent for the Act. He wanted to ensure that blacks were not " passing" as Virginia Indians, in his terms. Plecker directed local offices to use only the designations of "white" or "colored" on birth certificates, death certificates, marriage certificates, voter registration forms, etc. He further directed them to evaluate some specific families which he listed, and to change the classification of their records, saying he believed they were black and trying to pass as Indian.

During Plecker's time, many Virginia Indians and African Americans left the state to escape its segregationist strictures. Others tried to fade into the background until the storm passed. Plecker's "paper genocide" dominated state recordkeeping for more than two decades, but declined after he retired in 1946. It destroyed much of the documentation that had shown families continuing to identify as Indian.

The Racial Integrity Act was not repealed until 1967, after the ruling of the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

case '' Loving v. Virginia'', which stated anti-miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

laws were unconstitutional. In the ruling the court stated: "The freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race lies with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State."

In the late 1960s, two Virginia organizations applied for federal recognition through the BAR under the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Ani-Stohini/Unami first petitioned in 1968 and the Rappahannock filed shortly thereafter. The B.I.A. later told tribal leaders that they had lost the Ani-Stohini/Unami petition; they said that during the American Indian Movement

The American Indian Movement (AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement which was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota in July 1968, initially centered in urban areas in order to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and police br ...

takeover of the Interior Building in 1972, many documents were lost or destroyed. The Rappahannock tribe was recognized by the State of Virginia. Today, at least 13 tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confli ...

in Virginia have petitioned for federal recognition.

With the repeal of the Racial Integrity Act, individuals were allowed to have their birth certificates and other records changed to note their ethnic Indian identity (rather than black or white "racial" classification), but the state government charged a fee. After 1997, when Delegate Harvey Morgan's bill HB2889 passed to correct this injustice, any Virginia Indian who had been born in Virginia could have his or her records changed for free to indicate identity as Virginia Indian.

In the 1980s, the state officially recognized several tribes in a process authorized under legislation. The tribes had struggled to be recognized, against issues of racial discrimination. Because of their long history of interaction with European Americans, only two tribes had retained control of reservation lands established during the colonial period. Their "landless" condition added to their difficulty in documenting historic continuity of their people, as outsiders assumed that without a reservation, the Indians had assimilated to the majority culture. Another three tribes were recognized by the state in 2010.

21st century

The population of Powhatan Indians today in total is estimated to be about 8,500–9,500. About 3,000–3,500 are enrolled as tribal members in state-recognized tribes. In addition, theMonacan Nation

The Monacan Indian Nation is one of eleven Native American tribes recognized since the late 20th century by the U.S. state of Virginia. In January 2018, the United States Congress passed an act to provide federal recognition as tribes to the ...

has tribal membership of about 2,000.

The organized tribes, which developed from kinship and geographic communities, establish their own requirements for membership, as well as what they consider its obligations. Generally, members must pay dues; attend tribal meetings (which are usually monthly in the "home" areas); volunteer to serve as a tribal officer when asked; help to put on tribal events; belong to the tribal church (if one exists and they are able); teach their children their people's history and pass on traditional crafts; volunteer to represent the tribe at the Virginia Council on Indians, the United Indians of Virginia, or at other tribes' powwow

A powwow (also pow wow or pow-wow) is a gathering with dances held by many Native American and First Nations communities. Powwows today allow Indigenous people to socialize, dance, sing, and honor their cultures. Powwows may be private or p ...

s; speak at engagements for civic or school groups; and live in a good way, so as to best represent their tribe and Native Americans in general. Most Indian tribes maintain some traditions from before the time of European settlement, and are keen to pass these on to their children. Although Indians are also highly involved in non-native culture and employment, they regularly engage in activities for their individual tribes, including wearing regalia

Regalia is a Latin plurale tantum word that has different definitions. In one rare definition, it refers to the exclusive privileges of a sovereign. The word originally referred to the elaborate formal dress and dress accessories of a sovereig ...

and attending powwows, heritage festivals, and tribal homecomings. Individuals try to maintain a balance between elements of their traditional culture and participating in the majority culture.

The Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments ...

and the Mattaponi

The Mattaponi () tribe is one of only two Virginia Indian tribes in the Commonwealth of Virginia that owns reservation land, which it has held since the colonial era. The larger Mattaponi Indian Tribe lives in King William County on the reser ...

are the only tribes in Virginia to have maintained their reservations from the 17th-century colonial treaties. These two tribes continue to make their yearly tribute payment to the Virginia governor, as stipulated by the 1646 and 1677 treaties. Every year around Thanksgiving they hold a ceremony to pay the annual tribute of game, usually a deer, and pottery or a ceremonial pipe.

In 2013, the Virginia Department of Education released a 25-minute video, "The Virginia Indians: Meet the Tribes," covering both historical and contemporary Native American life in the state.

Tribes recognized by Virginia

The Commonwealth of Virginia passed legislation in 2001 to develop a process for state recognition of Native American tribes within the state. As of 2010, the state has recognized a total of 11 tribes, eight of them related to historic tribes that were members of the Powhatan paramountcy. The state also recognizes theMonacan Nation

The Monacan Indian Nation is one of eleven Native American tribes recognized since the late 20th century by the U.S. state of Virginia. In January 2018, the United States Congress passed an act to provide federal recognition as tribes to the ...

, the Nottoway, and the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), who were outside the paramountcy. Descendants of several other Virginia Indian and Powhatan-descended tribes still live in Virginia and other locations.

* Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe. Letter of Intent to Petition 12/30/2002. Receipt of Petition 12/30/2002. State recognized 2010; in Courtland, Southampton County

Southampton County is a county located on the southern border of the Commonwealth of Virginia. North Carolina is to the south. As of the 2020 census, the population was 17,996. Its county seat is Courtland.

History

In the early 17th centu ...

.

* Chickahominy Tribe

The Chickahominy are a federally recognized tribe of Virginian Native Americans who primarily live in Charles City County, located along the James River midway between Richmond and Williamsburg in the Commonwealth of Virginia. This area of the ...

. Letter of Intent to Petition 03/19/1996. State recognized 1983; in Charles City County

Charles City County is a county located in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated southeast of Richmond and west of Jamestown. It is bounded on the south by the James River and on the east by the Chickahominy River.

The ...

. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

* Eastern Chickahominy Indians Tribe Letter of Intent to Petition 9/6/2001. State recognized, 1983; in New Kent County. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

* Mattaponi

The Mattaponi () tribe is one of only two Virginia Indian tribes in the Commonwealth of Virginia that owns reservation land, which it has held since the colonial era. The larger Mattaponi Indian Tribe lives in King William County on the reser ...

Tribe (a.k.a. Mattaponi Indian Reservation). Letter of Intent to Petition 04/04/1995. State recognized 1983; in Banks of the Mattaponi River, King William County. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey have reservations based in colonial-era treaties ratified by the colony in 1658. Pamunkey Tribe's attorney told Congress in 1991 that the tribes state reservation originated in a treaty with the crown in the 17th century and has been occupied by Pamunkey since that time under strict requirements and following the treaty obligation to provide to the Crown a deer every year, and they've done that (replacing Crown with Governor of Commonwealth since Virginia became a Commonwealth)

* Monacan Nation

The Monacan Indian Nation is one of eleven Native American tribes recognized since the late 20th century by the U.S. state of Virginia. In January 2018, the United States Congress passed an act to provide federal recognition as tribes to the ...

(formerly Monacan Indian Tribe of Virginia). Letter of Intent to Petition 07/11/1995. State recognized 1989; in Bear Mountain, Amherst County

Amherst County is a county, located in the Piedmont region and near the center of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. The county is part of the Lynchburg Metropolitan Statistical Area, and its county seat is also named Amher ...

. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

* Nansemond Indian Tribal Association, Letter of Intent to Petition 9/20/2001. State recognized 1985; in Cities of Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

and Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

* Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia, recognized 2010; in Capron, Southampton County.

* Pamunkey Nation, recognized 1983; in Banks of the Pamunkey River, King William County. Federally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and A ...

2015.

* Patawomeck

Patawomeck is a Native American tribe based in Stafford County, Virginia, along the Potomac River. ''Patawomeck'' is another spelling of Potomac.

The Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia is a state-recognized tribe in Virginia that identifies ...

Indians of Virginia recognized 2010; in Stafford County.

* Rappahannock Indian Tribe (I) (formerly United Rappahannock Tribe). Letter of Intent to Petition 11/16/1979. State recognized 1983; in Indian Neck, King & Queen County. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

: An unrecognized tribe, Rappahannock Indian Tribe (II), also uses this name.

* Upper Mattaponi Tribe (formerly Upper Mattaponi Indian Tribal Association). Letter of Intent to Petition 11/26/1979. State recognized 1983; in King William County. In 2009, Senate Indian Affairs Committee endorsed a bill that would grant federal recognition.

In 2009 the governor established a Virginia Indian Commemorative Commission to develop a plan to run a competition for a monument to be located in Capitol Square to commemorate Native Americans in the state. Some elements have been developed, but the statue has not yet been installed.

Federal recognition

Various bills before Congress have proposed granting federal recognition for the six non-reservation Virginia Tribes. Recent sponsors of such Federal recognition bills have been Senator George Allen, R-Va and Rep.Jim Moran

James Patrick Moran Jr. (born May 16, 1945) is an American politician who served as the mayor of Alexandria, Virginia from 1985 to 1990, and as the U.S. representative for (including the cities of Falls Church and Alexandria, all of Arlington ...