Nancy Astor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Portrait of Nancy Langhorne Shaw Astor

by Edith Leeson Everett, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia *

Mirador Historical Marker

Albemarle County, Virginia *

www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk

* * *

UK Parliamentary Archives, Personal Papers of Mrs Bessie Le Cras, Parliamentary Agent for Lady Nancy Astor

{{DEFAULTSORT:Astor, Nancy 1879 births 1964 deaths 20th-century British women politicians American expatriates in England American emigrants to England Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Nancy British viscountesses Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Converts to Christian Science from Anglicanism Critics of the Catholic Church Edwardian era English Christian Scientists English suffragists Female members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Livingston family Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for constituencies in Devon Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Politicians from Danville, Virginia UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945 Politicians from Plymouth, Devon

Nancy Witcher Langhorne Astor, Viscountess Astor, (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a

The marriage was unhappy. Shaw's friends said Nancy became puritanical and rigid after marriage; her friends said that Shaw was an abusive

The marriage was unhappy. Shaw's friends said Nancy became puritanical and rigid after marriage; her friends said that Shaw was an abusive

Nancy Shaw had already become known in English society as an interesting and witty American, at a time when numerous wealthy young American women had married into the aristocracy. Her tendency to be saucy in conversation, yet religiously devout and almost prudish in behaviour, confused many of the English men but pleased some of the older socialites. Nancy also began to show her skill at winning over critics. She was once asked by an English woman, "Have you come to get our husbands?" Her unexpected response, "If you knew the trouble I had getting rid of mine..." charmed her listeners and displayed the wit for which she became known.Sykes (1984), p. 75

Nancy Shaw had already become known in English society as an interesting and witty American, at a time when numerous wealthy young American women had married into the aristocracy. Her tendency to be saucy in conversation, yet religiously devout and almost prudish in behaviour, confused many of the English men but pleased some of the older socialites. Nancy also began to show her skill at winning over critics. She was once asked by an English woman, "Have you come to get our husbands?" Her unexpected response, "If you knew the trouble I had getting rid of mine..." charmed her listeners and displayed the wit for which she became known.Sykes (1984), p. 75

She did marry an Englishman, albeit one born in the United States, Waldorf Astor; when he was twelve, his father,

She did marry an Englishman, albeit one born in the United States, Waldorf Astor; when he was twelve, his father,

Several elements of Viscountess Astor's life influenced her first campaign, but she became a candidate after her husband succeeded to the peerage and House of Lords. He had enjoyed a promising political career for several years before World War I in the

Several elements of Viscountess Astor's life influenced her first campaign, but she became a candidate after her husband succeeded to the peerage and House of Lords. He had enjoyed a promising political career for several years before World War I in the

Astor's Parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life. She gained attention as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules, often attributed to her American upbringing. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realising that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She learned to dress more sedately and avoided the bars and

Astor's Parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life. She gained attention as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules, often attributed to her American upbringing. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realising that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She learned to dress more sedately and avoided the bars and  During the 1920s, Astor made several effective speeches in Parliament, and gained support for her Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons under 18) Bill (nicknamed "Lady Astor's Bill"), raising the legal age for consuming alcohol in a

During the 1920s, Astor made several effective speeches in Parliament, and gained support for her Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons under 18) Bill (nicknamed "Lady Astor's Bill"), raising the legal age for consuming alcohol in a

Lady Astor believed her party and her husband caused her retirement in 1945. As the Conservatives believed she had become a political liability in the final years of World War II, her husband said that if she stood for office again the family would not support her. She conceded but, according to contemporary reports, was both irritated and angry about her situation.Sykes (1984), pp. 554–56Thornton (1997)

Lady Astor struggled in retirement, which put further strain on her marriage. In a speech commemorating her 25 years in parliament, she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began travelling separately and soon were living apart. Lord Astor also began moving towards

Lady Astor believed her party and her husband caused her retirement in 1945. As the Conservatives believed she had become a political liability in the final years of World War II, her husband said that if she stood for office again the family would not support her. She conceded but, according to contemporary reports, was both irritated and angry about her situation.Sykes (1984), pp. 554–56Thornton (1997)

Lady Astor struggled in retirement, which put further strain on her marriage. In a speech commemorating her 25 years in parliament, she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began travelling separately and soon were living apart. Lord Astor also began moving towards

broadcast a nine-part television drama serial about her life, ''Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP), serving from 1919 to 1945.

Astor's first husband was American Robert Gould Shaw II; the couple separated after four years and divorced in 1903. She moved to England and married Waldorf Astor. After her husband succeeded to the peerage and entered the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

, she entered politics as a member of the Conservative Party and won his former seat of Plymouth Sutton

Plymouth, Sutton was, from 1918 until 2010, a borough constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elected one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election.

History

Pl ...

in 1919, becoming the first woman to sit as an MP in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

. She served in Parliament until 1945, when she was persuaded to step down. Astor has been criticised for her antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and sympathetic view of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

.

Early life

Nancy Witcher Langhorne was born at theLanghorne House

Langhorne House, also known as the Gwynn Apartments, is an historic late 19th-century house in Danville, Virginia later enlarged and used as an apartment house. Its period of significance is 1922, when Nancy Langhorne Astor, by then known as Lad ...

in Danville, Virginia

Danville is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States, located in the Southside Virginia region and on the fall line of the Dan River. It was a center of tobacco production and was an area of Confederate activity ...

. She was the eighth of eleven children born to railroad businessman Chiswell Dabney Langhorne and Nancy Witcher Keene. Following the abolition of slavery, Chiswell struggled to make his operations profitable, and with the destruction of the war, the family lived in near-poverty for several years before Nancy was born. After her birth, her father gained a job as a tobacco auctioneer in Danville, the centre of bright leaf tobacco and a major marketing and processing centre.

In 1874, he won a construction contract with the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad, using former contacts from his service in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. By 1892, when Nancy was thirteen years old, her father had re-established his wealth and built a sizeable home. Chiswell Langhorne later moved his family to an estate, known as '' Mirador'', in Albemarle County, Virginia.

Nancy Langhorne had four sisters and three brothers who survived childhood. All of the sisters were known for their beauty; Nancy and her sister Irene both attended a finishing school in New York City. There Nancy met her first husband, socialite Robert Gould Shaw II, a first cousin of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw

Robert Gould Shaw (October 10, 1837 – July 18, 1863) was an American officer in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Born into a prominent Boston abolitionist family, he accepted command of the first all-black regiment (the 54th Mas ...

, who commanded the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the first unit in the Union Army to be composed of African Americans. They married in New York City on 27 October 1897, when she was 18.

alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomina ...

. During their four-year marriage, they had one son, Robert Gould Shaw III

Robert Gould Shaw III (18 August 1898 – 10 July 1970) was an American-born English socialite. He was the only child of Nancy Witcher Langhorne and Robert Gould Shaw II, a landowner and socialite. After his parents' divorce in 1903, he moved ...

(called Bobbie). Nancy left Shaw numerous times during their marriage, the first during their honeymoon. In 1903, Nancy's mother died; at that time, Nancy Shaw gained a divorce and moved back to ''Mirador'' to try to run her father's household, but was unsuccessful.

Nancy Shaw took a tour of England and fell in love with the country. Since she had been so happy there, her father suggested that she move to England. Seeing she was reluctant, her father said this was also her mother's wish; he suggested she take her younger sister Phyllis. Nancy and Phyllis moved together to England in 1905. Their older sister Irene had married the artist Charles Dana Gibson

Charles Dana Gibson (September 14, 1867 – December 23, 1944) was an American illustrator. He was best known for his creation of the Gibson Girl, an iconic representation of the beautiful and independent Euro-American woman at the turn of the ...

and became a model for his Gibson Girl

The Gibson Girl was the personification of the feminine ideal of physical attractiveness as portrayed by the pen-and-ink illustrations of artist Charles Dana Gibson during a 20-year period that spanned the late 19th and early 20th centuries in th ...

s.

England

She did marry an Englishman, albeit one born in the United States, Waldorf Astor; when he was twelve, his father,

She did marry an Englishman, albeit one born in the United States, Waldorf Astor; when he was twelve, his father, William Waldorf Astor

William Waldorf "Willy" Astor, 1st Viscount Astor (31 March 1848 – 18 October 1919) was an American-British attorney, politician, businessman (hotels and newspapers), and philanthropist. Astor was a scion of the very wealthy Astor family of ...

had moved the family to England, raising his children in the English aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

style. The couple were well matched, as they were both American expatriate

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country. In common usage, the term often refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, or artists taking positions outside their home country, either ...

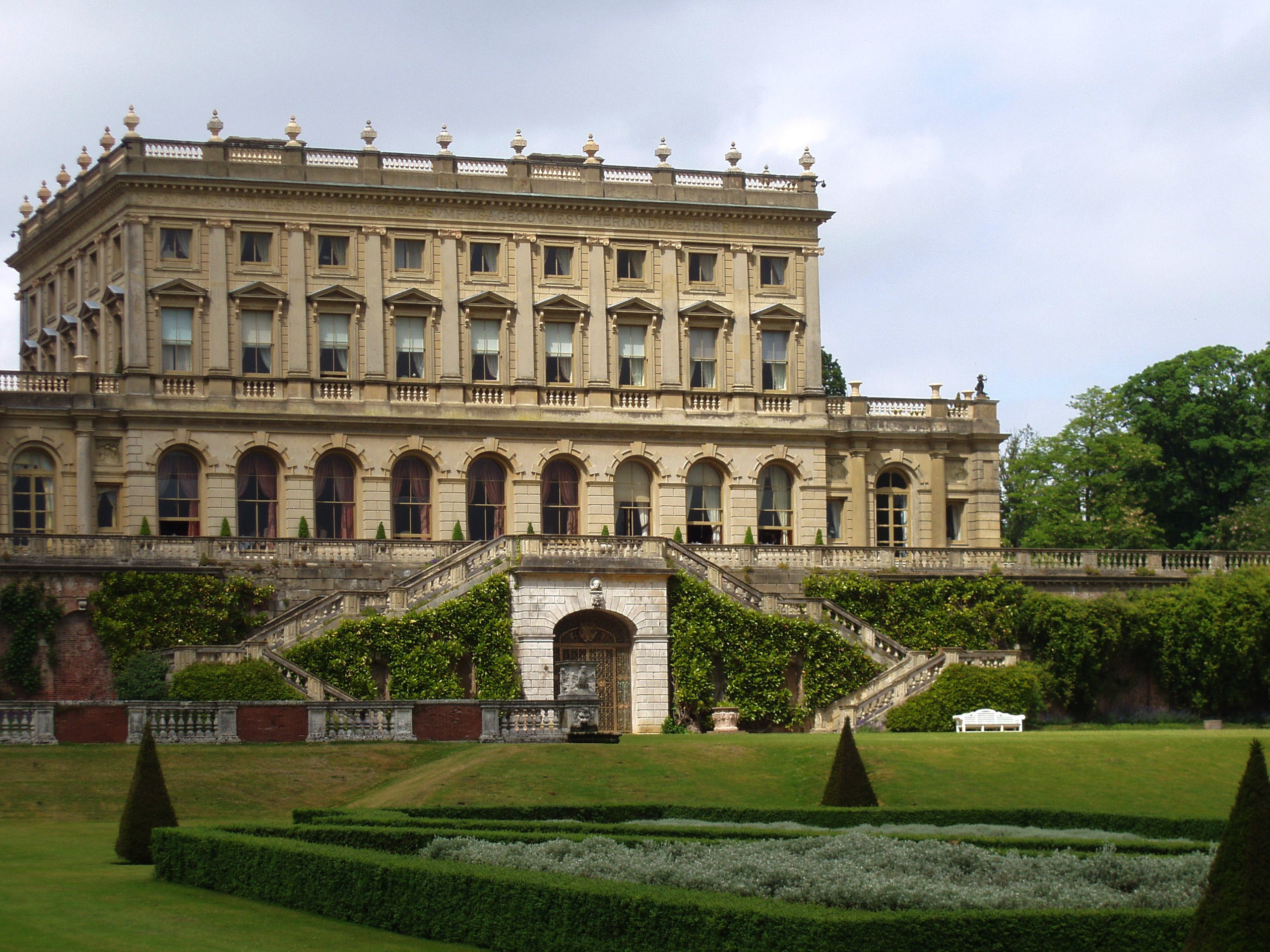

s with similar temperaments. They were of the same age, and born on the same day, 19 May 1879. Astor shared some of Nancy's moral attitudes, and had a heart condition that may have contributed to his restraint. After the marriage, the Astors moved into Cliveden

Cliveden (pronounced ) is an English country house and estate in the care of the National Trust in Buckinghamshire, on the border with Berkshire. The Italianate mansion, also known as Cliveden House, crowns an outlying ridge of the Chiltern ...

, a lavish estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

that was a wedding gift from Astor's father. Nancy Astor developed as a prominent hostess for the social elite.

The Astors also owned a grand London house, No. 4 St. James's Square, now the premises of the Naval & Military Club. A blue plaque unveiled in 1987 commemorates Astor at St. James's Square. Through her many social connections, Lady Astor became involved in a political circle called Milner's Kindergarten

Milner's Kindergarten is the informal name of a group of Britons who served in the South African Civil Service under High Commissioner Alfred, Lord Milner, between the Second Boer War and the founding of the Union of South Africa in 1910. It ...

. Considered liberal in their age, the group advocated unity and equality among English-speaking people and a continuance or expansion of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

.

Religious views

With Milner's Kindergarten, Astor began her association withPhilip Kerr

Philip Ballantyne Kerr (22 February 1956 – 23 March 2018) was a British author, best known for his Bernie Gunther series of historical detective thrillers.

Early life

Kerr was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, where his father was an enginee ...

. The friendship became important in her religious life; they met shortly after Kerr had suffered a spiritual crisis regarding his once devout Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. They were attracted to Christian Science, to which they both eventually converted. After converting, she began to proselytise for that faith and played a role in Kerr's conversion to it. She also tried to convert Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

's daughters to Christian Science, which led to a rift between them.

Despite having Catholic friends such as Belloc for a time, Astor had religious views that included a strong vein of anti-Catholicism. Christopher Sykes argues that Kerr, an ex-Catholic, influenced this, but others argue that Astor's Protestant Virginia origins are a sufficient explanation for her Anti-Catholic views. (Anti-Catholicism was also tied to historic national rivalries.)

She attempted to discourage the hiring of Jews or Catholics to senior positions at ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

'', a newspaper owned by her husband. In 1927, she reportedly told James Louis Garvin

James Louis Garvin CH (12 April 1868 – 23 January 1947) was a British journalist, editor, and author. In 1908, Garvin agreed to take over the editorship of the Sunday newspaper ''The Observer'', revolutionising Sunday journalism and restori ...

that if he hired a Catholic, "bishops would be there within a week."

First campaign for Parliament

Several elements of Viscountess Astor's life influenced her first campaign, but she became a candidate after her husband succeeded to the peerage and House of Lords. He had enjoyed a promising political career for several years before World War I in the

Several elements of Viscountess Astor's life influenced her first campaign, but she became a candidate after her husband succeeded to the peerage and House of Lords. He had enjoyed a promising political career for several years before World War I in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

; after his father's death, he succeeded to his father's peerage as the 2nd Viscount Astor

Viscount Astor, of Hever Castle in the County of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1917 for the financier and statesman William Waldorf Astor, 1st Baron Astor. He had already been created Baron Astor, of ...

. He automatically became a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

and consequently had to forfeit his seat of Plymouth Sutton

Plymouth, Sutton was, from 1918 until 2010, a borough constituency represented in the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It elected one Member of Parliament (MP) by the first past the post system of election.

History

Pl ...

in the House of Commons. With this change, Lady Astor decided to contest the by-election for the vacant Parliamentary seat.

Astor had not been connected with the women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

movement in the British Isles. The first woman elected to the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

, Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the firs ...

, said Lady Astor was "of the upper classes, out of touch". Countess Markiewicz had been in Holloway prison

HM Prison Holloway was a closed category prison for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

Histor ...

for Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

activities during her election, and other suffragettes had been imprisoned for arson. However, as Astor was met as she arrived at Paddington station on the day after her election by a crowd of suffragettes, including unnamed women who had been imprisoned and on hunger strike, one said, "This is the beginning of our era. I am glad to have suffered for this."

Astor was hampered in the popular campaign for her published and at times vocal teetotalism

Teetotalism is the practice or promotion of total personal abstinence from the psychoactive drug alcohol, specifically in alcoholic drinks. A person who practices (and possibly advocates) teetotalism is called a teetotaler or teetotaller, or is ...

and her ignorance of current political issues. Astor appealed to voters on the basis of her earlier work with the Canadian soldiers, allies of the British, charitable work during the war, her financial resources for the campaign and her ability to improvise. Her audiences appreciated her wit and ability to turn the tables on hecklers. Once a man asked her what the Astors had done for him and she responded with, "Why, Charlie, you know," and later had a picture taken with him. This informal style baffled yet amused the British public. She rallied the supporters of the current government, moderated her Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

views, and used women's meetings to gain the support of female voters. A by-election was held on 28 November 1919, and she took up her seat in the House on 1 December as a Unionist (also known as "Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

") Member of Parliament.

Viscountess Astor was not the first woman elected to the Westminster Parliament. That was achieved by Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, nationalist, suffragist, socialist, and the firs ...

, who was the first woman MP elected to Westminster in 1918, but as she was an Irish Republican, she did not take her seat. As a result, Lady Astor is sometimes erroneously referred to as the first woman MP, or the first woman elected to the U.K. Parliament, rather than the first woman MP to take her seat in Parliament.

Astor was the first woman to be elected through what has been termed the 'halo effect' of women taking over their husband's parliamentary seat, a process which accounted for the election of ten women MPs (nearly a third of the women elected to parliament) between the two world wars.

Early years in Parliament

Astor's Parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life. She gained attention as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules, often attributed to her American upbringing. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realising that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She learned to dress more sedately and avoided the bars and

Astor's Parliamentary career was the most public phase of her life. She gained attention as a woman and as someone who did not follow the rules, often attributed to her American upbringing. On her first day in the House of Commons, she was called to order for chatting with a fellow House member, not realising that she was the person who was causing the commotion. She learned to dress more sedately and avoided the bars and smoking room

A smoking room (or smoking lounge) is a room which is specifically provided and furnished for smoking, generally in buildings where smoking is otherwise prohibited.

Locations and facilities

Smoking rooms can be found in public buildings suc ...

s frequented by the men.Sykes (1984), p. 238Masters (1981), p. 100

Early in her first term, MP Horatio Bottomley

Horatio William Bottomley (23 March 1860 – 26 May 1933) was an English financier, journalist, editor, newspaper proprietor, swindler, and Member of Parliament. He is best known for his editorship of the popular magazine ''John Bull (maga ...

wanted to dominate the "soldier's friend" issue and, believing her to be an obstacle, sought to ruin her political career. He capitalised on her opposition to divorce reform and her efforts to maintain wartime alcohol restrictions. Bottomley portrayed her as a hypocrite, as she was divorced. He said that the reform bill that she opposed would allow women to have the same kind of divorce she had in America. Bottomley was later imprisoned for fraud, which Astor used to her advantage in other campaigns.Sykes (1984), pp. 242–60

Astor made friends among women MPs, including members of the other parties. Margaret Wintringham

Margaret Wintringham (née Longbottom; 4 August 1879 – 10 March 1955) was a British Liberal Party politician. She was the second woman, and the first British-born woman, to take her seat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.

Early ...

was elected after Astor had been in office for two years. Astor befriended Ellen Wilkinson

Ellen Cicely Wilkinson (8 October 1891 – 6 February 1947) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Minister of Education from July 1945 until her death. Earlier in her career, as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Jarrow, s ...

, a member of the Labour Party (and a former Communist). Astor later proposed creating a "Women's Party", but the female Labour MPs opposed that, as their party was then in office and had promised them positions. Over time, political differences separated the women MPs; by 1931 Astor became hostile to female Labour members such as Susan Lawrence.Sykes (1984), pp. 266–67, 354, 377Masters (1981), p. 137

Nancy Astor's accomplishments in the House of Commons were relatively minor. She never held a position with much influence and or any post of ministerial rank although her time in Commons saw four Conservative Prime Ministers in office. The Duchess of Atholl (elected to Parliament in 1923, four years after Lady Astor) rose to higher levels in the Conservative Party before Astor. Astor felt if she had more position in the party, she would be less free to criticise her party's government.

During this period, Nancy Astor continued to be active outside government by supporting the development and expansion of nursery schools for children's education. She was introduced to the issue by socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

Margaret McMillan

Margaret McMillan (20 July 1860 – 27 March 1931) was a nursery school pioneer and lobbied for the 1906 Provision of School Meals Act. Working in deprived districts of London, notably Deptford, and Bradford, she agitated for reforms to ...

, who believed that her late sister helped guide her in life. Lady Astor was initially skeptical of that aspect, but the two women later became close. Astor used her wealth to aid their social efforts.Sykes (1984), pp. 329–30Masters (1981), p. 140

Although active in charitable efforts, Astor became noted for a streak of cruelty. On hearing of the death of a political enemy, she expressed her pleasure. When people complained, she did not apologise but said, "I'm a Virginian; we shoot to kill." Angus McDonnell

The Honourable Angus McDonnell (7 June 1881 – 22 April 1966) was a British engineer, diplomat and Conservative Party politician.

Early life

He was the second son of William Randal McDonnell, 6th Earl of Antrim and Louisa McDonnell, Countes ...

, a Virginia friend, angered her by marrying without consulting her on his choice. She later told him, regarding his maiden speech, that he "really must do better than that." During the course of her adult life, Astor alienated many with her sharp words as well.Sykes (1984), pp. 285, 326Masters (1981), p. 58

During the 1920s, Astor made several effective speeches in Parliament, and gained support for her Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons under 18) Bill (nicknamed "Lady Astor's Bill"), raising the legal age for consuming alcohol in a

During the 1920s, Astor made several effective speeches in Parliament, and gained support for her Intoxicating Liquor (Sale to Persons under 18) Bill (nicknamed "Lady Astor's Bill"), raising the legal age for consuming alcohol in a public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

from 14 to 18.Sykes (1984), pp. 299–309, 327 Her wealth and persona brought attention to women who were serving in government. She worked to recruit women into the civil service, the police force, education reform

Education reform is the name given to the goal of changing public education. The meaning and education methods have changed through debates over what content or experiences result in an educated individual or an educated society. Historically, t ...

, and the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

. She was well-liked in her constituency, as well as the United States during the 1920s, but her success is generally believed to have declined in the following decades.Sykes (1984), pp. 317–8 327–8Masters (1981), pp. 115–18

In May 1922, Astor was guest of honour at a Pan-American conference held by the League of Women Voters in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

.

Astor became the first President of the newly-formed Electrical Association For Women

The Electrical Association for Women (EAW) was a feminist and educational organisation founded in Great Britain in 1924 to promote the benefits of electricity in the home.

History

The Electrical Association for Women developed in 1924 from a p ...

in 1924.

She chaired the first ever International Conference of Women In Science, Industry and Commerce, a three-day event held London in July 1925, organised by Caroline Haslett

Dame Caroline Harriet Haslett DBE, JP (17 August 1895 – 4 January 1957) was an English electrical engineer, electricity industry administrator and champion of women's rights.

She was the first secretary of the Women's Engineering Society a ...

for the Women's Engineering Society

The Women's Engineering Society is a United Kingdom professional learned society and networking body for women engineers, scientists and technologists. It was the first professional body set up for women working in all areas of engineering, pred ...

in co-operation with other leading women's groups. Astor hosted a large gathering at her home in St James's to enable networking amongst the international delegates, and spoke strongly of her support of and the need for women to work in the fields of science, engineering and technology.

She was concerned about the treatment of juvenile victims of crime: "The work of new MPs, such as Nancy Astor, led to a Departmental Committee on Sexual Offences Against Young People, which reported in 1925."

1930s

The 1930s were a decade of personal and professional difficulty for Lady Astor. In 1929, she won a narrow victory over the Labour candidate. In 1931, Bobby Shaw, her son from her first marriage, was arrested for homosexual offences. As her son had previously shown tendencies towards alcoholism and instability, Astor's friendPhilip Kerr

Philip Ballantyne Kerr (22 February 1956 – 23 March 2018) was a British author, best known for his Bernie Gunther series of historical detective thrillers.

Early life

Kerr was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, where his father was an enginee ...

, now the 11th Marquess of Lothian, suggested the arrest might act as a catalyst for him to change his behaviour, but he was incorrect.

Astor made a disastrous speech stating that alcohol use was the reason for England's national cricket team being defeated by the Australian national cricket team

The Australia men's national cricket team represents Australia in men's international cricket. As the joint oldest team in Test cricket history, playing in the first ever Test match in 1877, the team also plays One-Day International (ODI) an ...

. Both the English and Australian teams objected to that statement. Astor remained oblivious to her growing unpopularity almost to the end of her career.Sykes (1984), pp. 351–52, 371–80Masters (1981), pp. 161–68

Astor's friendship with George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

helped her through some of her problems although his own nonconformity caused friction between them. They held opposing political views and had very different temperaments. However, his own tendency to make controversial statements or put her into awkward situations proved to be a drawback for her political career.Sykes (1984), pp. 382–95Masters (1981), pp. 145–49, 170–75

After Bobby Shaw was arrested, Gertrude Ely, a Pennsylvania Railroad heiress from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Bryn Mawr, pronounced ,

from Welsh language, Welsh for big hill, is a census-designated place (CDP) located across three townships: Radnor Township, Pennsylvania, Radnor Township and Haverford Township, Pennsylvania, Haverford Township in Delaw ...

offered to provide a guided tour to Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

for Lady Astor and Bobby. Because of public comments by her and her son during this period, her political career suffered. Her son made many flattering statements about the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, and Astor often disparaged it because she did not approve of communism. In a meeting, she asked Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

directly why he had slaughtered so many Russians, but many of her criticisms were translated as less challenging statements. Some of her conservative supporters feared she had "gone soft" on communism; her question to Stalin may have been translated correctly only because he insisted of being told what she had said. The Conservatives felt that her son's praise of the Soviet Union served as a coup for its propaganda and so they were unhappy with her tour.Masters (1981), pp. 170–75

Antisemitism, anti-Catholicism, and anticommunism

Astor was reportedly a supporter of theNazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

as a solution to what she saw as the "world problems" of Jews and communists. In 1938, she met Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy (September 6, 1888 – November 18, 1969) was an American businessman, investor, and politician. He is known for his own political prominence as well as that of his children and was the patriarch of the Irish-American Ke ...

, who was a well-documented antisemite. She asked him not to take offence at her anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

views and wrote, "I'm glad you are smart enough not to take my iewspersonally". She highlighted the fact that she had a number of Catholic friends. Astor and Kennedy's correspondence is reportedly filled with antisemitic language, and Edward J. Renehan Jr. wrote:

As fiercely anti-Communist as they were anti-Semitic, Kennedy and Astor looked uponAstor commented to Kennedy that Hitler would have to do worse than "give a rough time... to the killers of christ" for Britain and America to risk "Armageddon to save them. The wheel of history swings round as the Lord would have it. Who are we to stand in the way of the future?" Astor made various other documented anti-Semitic comments, such as her complaint that the ''Observer'' newspaper, which was owned at the time by her husband, was "full of homosexuals and Jews", and her tense antisemitic exchange with MP Alan Graham in 1938, as described by Harold Nicolson: David Feldman of the Pears Institute for the Study of Anti-Semitism has also related that whilst attending a dinner at the Savoy Hotel in 1934, Astor asked theAdolf Hitler Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...as a welcome solution to both of these "world problems" (Nancy's phrase). ... Kennedy replied that he expected the " Jew media" in the United States to become a problem, that "Jewish pundits in New York and Los Angeles" were already making noises contrived to "set a match to the fuse of the world".

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

' High Commissioner for Refugees whether he believed "that there must be something in the Jews themselves that had brought them persecution throughout the ages". Dr Feldman acknowledged, however, that it was "not an unusual view" and explained it "was a conventional idea in the UK at the time". Some years later, during a visit to New York in 1947, she apparently "clashed" with reporters, renouncing her anti-Semitism, telling one that she was "not anti-Jewish but gangsterism isn't going to solve the Palestine problem".

Astor was also deeply involved in the so-called Cliveden Set, a coterie of aristocrats that was described by one journalist as having subscribed to their own form of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. In that capacity, Astor was considered a "legendary hostess" for the group that in 1936 welcomed Hitler's foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, who communicated to Hitler regarding the likelihood of an agreement between Germany and England and singled out the ''Astorgruppe'' as one of the circles "that want a fresh understanding with Germany and who hold that it would not basically be impossible to achieve". The Sunday newspaper ''Reynolds News'', also reported, "Cliveden has been the centre of friendship with German influence". To that end, several of her friends and associates, especially the Marquess of Lothian, were involved in the policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Astor, however, was worried that the group might be viewed as a pro-German conspiracy, and her husband, William Waldorf Astor, wrote in a letter to the ''Times'', "To link our weekends with any particular clique is as absurd as is the allegation that those of us who desire to establish better relations with Germany or Italy are pro-Nazis or pro-Fascists". The Cliveden Set was also depicted by war agitators as the prime movers for peace.

At the request of her friend Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

, a future US Supreme Court justice who was Jewish, Astor intervened with the Nazis in Vienna and secured the release of Frankfurter's Jewish uncle, Solomon.: Relates how she told Alan Crosland Graham "Only a Jew like you would dare to be rude to me" Astor occasionally met with Nazi officials in keeping with Neville Chamberlain's policies, and she was known to distrust and to dislike British Foreign Secretary (later Prime Minister) Anthony Eden. She is alleged to have told one Nazi official that she supported German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germ ...

because the country was "surrounded by Catholics". She also told Ribbentrop, the German ambassador, who later became the foreign minister of Germany, that Hitler looked too much like Charlie Chaplin to be taken seriously. Those statements are the only documented incidents of her direct expressions to Nazis.Masters (1981), pp. 185–192Sykes (1984), pp. 440–450

Astor became increasingly harsh in her anti-Catholic and anti-communist sentiments. After the passage of the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, she said that if the Czech refugees fleeing Nazi oppression were communists, they should seek asylum with the Soviets, instead of the British. While supporters of appeasement felt that to be out of line, the Marquess of Lothian encouraged her comments.Sykes (1984), pp. 446–453, 468

World War II

WhenWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

began, Astor admitted that she had made mistakes, and voted against Chamberlain, but left-wing hostility to her politics remained. In a 1939 speech, the Labour MP Stafford Cripps called her "The Member for Berlin".

Astor's fear of Catholics increased and she made a speech saying that a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

conspiracy was subverting the Foreign Office. Based on her opposition to Communists, she insulted Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's role (from 1941) as one of the Allied Powers during the war. Her speeches became rambling and incomprehensible; an opponent said that debating her had become "like playing squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

with a dish of scrambled eggs

Scrambled eggs is a dish made from eggs (usually chicken eggs) stirred, whipped or beaten together while being gently heated, typically with salt, butter, oil and sometimes other ingredients.

Preparation

Only eggs are necessary to make scramble ...

". On one occasion she accosted a young American soldier outside the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

. "Would you like to go in?" she asked. The GI replied: "You are the sort of woman my mother told me to avoid".

The period from 1937 to the end of the war was personally difficult for Astor: in January of that year she lost her sister Phyllis, followed by her only surviving brother in 1938. In 1940, the Marquess of Lothian died. He had been her closest Christian Scientist friend even after her husband converted. George Bernard Shaw's wife died three years later. During the war, Astor's husband had a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

. After this, their marriage grew cold, likely due to her subsequent discomfort with his health problems. She ran a hospital for Canadian soldiers as she had during the First World War, but openly expressed a preference for the earlier soldiers.Sykes (1984), pp. 520–522, 534Masters (1984), pp. 200–205Thornton (1997), p. 434

It was generally believed that it was Lady Astor who, during a World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

speech, first referred to the men of the 8th Army who were fighting in the Italian campaign as the " D-Day Dodgers". Observers thought she was suggesting they were avoiding the "real war" in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and the future invasion. The Allied soldiers in Italy were so incensed that Major Hamish Henderson

Hamish Scott Henderson (11 November 1919 – 9 March 2002) was a Scottish poet, songwriter, communist, intellectual and soldier.

He was a catalyst for the folk revival in Scotland. He was also an accomplished folk song collector and dis ...

of the 51st Highland Division

The 51st (Highland) Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War from 1915 to 1918. The division was raised in 1908, upon the creation of the Territorial Force, as ...

composed a bitingly sarcastic song to the tune of the popular German song "Lili Marleen

"Lili Marleen" (also spelled "Lili Marlen'", "Lilli Marlene", "Lily Marlene", "Lili Marlène" among others; ) is a German love song that became popular during World War II throughout Europe and the Mediterranean among both Axis and Allied troo ...

", called "The Ballad of the D-Day Dodgers". This song has also been attributed to Lance-Sergeant Harry Pynn of the Tank Rescue Section, 19 Army Fire Brigade.

When told she was one of the people listed to be arrested, imprisoned and face possible execution in " The Black Book" under a German invasion of Britain

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

, Lady Astor commented: "It is the complete answer to the terrible lie that the so-called ' Cliveden Set' was pro-Fascist."

Final years

Lady Astor believed her party and her husband caused her retirement in 1945. As the Conservatives believed she had become a political liability in the final years of World War II, her husband said that if she stood for office again the family would not support her. She conceded but, according to contemporary reports, was both irritated and angry about her situation.Sykes (1984), pp. 554–56Thornton (1997)

Lady Astor struggled in retirement, which put further strain on her marriage. In a speech commemorating her 25 years in parliament, she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began travelling separately and soon were living apart. Lord Astor also began moving towards

Lady Astor believed her party and her husband caused her retirement in 1945. As the Conservatives believed she had become a political liability in the final years of World War II, her husband said that if she stood for office again the family would not support her. She conceded but, according to contemporary reports, was both irritated and angry about her situation.Sykes (1984), pp. 554–56Thornton (1997)

Lady Astor struggled in retirement, which put further strain on her marriage. In a speech commemorating her 25 years in parliament, she stated that her retirement was forced on her and that it should please the men of Britain. The couple began travelling separately and soon were living apart. Lord Astor also began moving towards left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soc ...

in his last years, and that exacerbated their differences. However, the couple reconciled before his death on 30 September 1952.Sykes (1984), pp. 556–57, 573–75Thornton (1997), p. 444

Lady Astor's public image suffered, as her ethnic and religious views were increasingly out of touch with cultural changes in Britain. She expressed a growing paranoia

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of conspiracy co ...

regarding ethnic minorities. In one instance, she stated that the President of the United States had become too dependent on New York City. To her this city represented "Jewish and foreign" influences that she feared. During a US tour, she told a group of African-American students that they should aspire to be like the black servants she remembered from her youth. On a later trip, she told African-American church members that they should be grateful for slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

because it had allowed them to be introduced to Christianity. In Rhodesia she proudly told the white minority government leaders that she was the daughter of a slave owner.Sykes (1984), pp. 580, 586–94, 601–06

After 1956, Nancy Astor became increasingly isolated. In 1959, she was honoured by receiving the Freedom of City of Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth' ...

. By this time, she had lost all her sisters and brothers, her colleague "Red Ellen" Wilkinson died in 1947, George Bernard Shaw died in 1950, and she did not take well to widowhood. Her son Bobbie Shaw became increasingly combative and after her death he committed suicide. Her son, Jakie, married a prominent Catholic woman, which hurt his relationship with his mother. She and her other children became estranged. Gradually she began to accept Catholics as friends. However, she said that her final years were lonely.

Lady Astor died in 1964 at her daughter Nancy Astor's home at Grimsthorpe Castle

Grimsthorpe Castle is a country house in Lincolnshire, England north-west of Bourne on the A151. It lies within a 3,000 acre (12 km2) park of rolling pastures, lakes, and woodland landscaped by Capability Brown. While Grimsthorpe is not a ...

in Lincolnshire. She was cremated and her ashes interred at the Octagon Temple at Cliveden.

Alleged quotations

She was known for exchanges withWinston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, though most of these are not well documented. Churchill told Lady Astor that having a woman in Parliament was like having one intrude on him in the bathroom, to which she retorted, "You're not handsome enough to have such fears."

Lady Astor is also said to have responded to a question from Churchill about what disguise he should wear to a masquerade ball by saying, "Why don't you come sober, Prime Minister?"

Although variations on the following anecdote exist with different people, the story is being told of Winston Churchill's encounter with Lady Astor who, after failing to shake him in an argument, broke off with the petulant remark, "Oh, if you were my husband, I'd put poison in your tea." "Madame," Winston responded, "if I were your husband, I'd drink it with pleasure."

On another occasion, Lady Astor allegedly came upon Churchill, and he was highly intoxicated. She highly disapproved of alcohol, and she said to him "Winston, you're drunk!" To which he replied "And you are ugly. However, when I wake up tomorrow, I shall be sober, and you will still be ugly!"

Legacy

In 1982 theBBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Nancy Astor

Nancy Witcher Langhorne Astor, Viscountess Astor, (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945.

Astor's first husband was America ...

'', which starred Lisa Harrow. A bronze statue of Lady Astor was installed in Plymouth, near her former family home, in 2019 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of her election to Parliament.

Astor's antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

has been widely documented and has been criticised in recent years, particularly in light of former Prime Minister Theresa May

Theresa Mary May, Lady May (; née Brasier; born 1 October 1956) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2016 to 2019. She previously served in David Cameron's cabi ...

's 2019 unveiling of a statue in her honour with Prime Minister Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (; born 19 June 1964) is a British politician, writer and journalist who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He previously served as F ...

in attendance, and more recently after Labour MP Rachel Reeves

Rachel Jane Reeves (born 13 February 1979) is a British politician and economist serving as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer since 2021. A member of the Labour Party, she has been Member of Parliament for Leeds West since 2010.

Born in Lewis ...

commemorated Astor in a series of tweets. The then-leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

, while opposed to her anti-semitism, recognised she was the first woman MP to take up her place in Parliament and so praised installation of the statue, commenting "I'm really pleased the statue is going up".

During the George Floyd protests

The George Floyd protests were a series of protests and civil unrest against police brutality and racism that began in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020, and largely took place during 2020. The civil unrest and protests began as part of internat ...

in 2020, the word "Nazi" was spray-painted on its base. The statue was on a list published on a website called ''Topple the Racists''.

Children

#Robert Gould Shaw III

Robert Gould Shaw III (18 August 1898 – 10 July 1970) was an American-born English socialite. He was the only child of Nancy Witcher Langhorne and Robert Gould Shaw II, a landowner and socialite. After his parents' divorce in 1903, he moved ...

(1898–1970)

# William Waldorf Astor II (1907–1966)

# Nancy Phyllis Louise Astor (1909–1975)

# Francis David Langhorne Astor (1912–2001)

# Michael Langhorne Astor

The Hon. Michael Langhorne Astor (10 April 1916 – 28 February 1980) was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician.

Early life

Michael Astor was born on 10 April 1916. He was the fourth child of Waldorf Astor, 2nd Visco ...

(1916–1980)

# John Jacob Astor VII "Jakie" (1918–2000)

Notes

References

Sources

* Astor, Michael, ''Tribal Feelings'' (Readers Union, 1964) * Cowling, Maurice, ''The Impact of Hitler: British Policies and Policy 1933–1940'',Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambridge University Pre ...

, 1975, p. 402,

*

* Musolf, Karen J., ''From Plymouth to Parliament'' (St. Martin's Press, 1999)

*

*

*

* Wearing, J. P. (editor), ''Bernard Shaw and Nancy Astor'' (University of Toronto Press, 2005)

Further reading

* Harrison, Rosina, ''Rose: My Life in Service to Lady Astor'', (Penguin Books, 2011).External links

* * * * *Portrait of Nancy Langhorne Shaw Astor

by Edith Leeson Everett, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia *

Mirador Historical Marker

Albemarle County, Virginia *

www.cracroftspeerage.co.uk

* * *

UK Parliamentary Archives, Personal Papers of Mrs Bessie Le Cras, Parliamentary Agent for Lady Nancy Astor

{{DEFAULTSORT:Astor, Nancy 1879 births 1964 deaths 20th-century British women politicians American expatriates in England American emigrants to England Antisemitism in the United Kingdom Nancy British viscountesses Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Converts to Christian Science from Anglicanism Critics of the Catholic Church Edwardian era English Christian Scientists English suffragists Female members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies Livingston family Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for constituencies in Devon Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Politicians from Danville, Virginia UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929 UK MPs 1929–1931 UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945 Politicians from Plymouth, Devon