Namara inscription on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Namara inscription ( ar, نقش النمارة ') is a 4th century inscription in the

Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads

Jan Retso, pp. 467–

The Arabic Language

By Kees Versteegh, pp. 31–36

Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century

Irfan Shahid, pp. 31–53

The Early Alphabet

John F. Healey, p.54 * http://www.indiana.edu/~arabic/arabic_history.htm

Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet

J. T. Hooker, p.248 {{Louvre Museum 328 works 4th-century inscriptions 1901 archaeological discoveries Ancient Syria Arabic inscriptions Nabataean script History of Saudi Arabia Near East and Middle East antiquities of the Louvre

Arabic language

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, making it one of the earliest. It has also been interpreted as a late version of the Nabataean Aramaic

Nabataean Aramaic is the Aramaic variety used in inscriptions by the Nabataeans of the East Bank of the Jordan River, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula. Compared to other varieties of Aramaic, it is notable for the occurrence of a number of loa ...

language in its transition to Arabic. It has been described by Irfan Shahid

In Islam, ‘Irfan (Arabic/Persian/Urdu: ; tr, İrfan), literally ‘knowledge, awareness, wisdom’, is gnosis. Islamic mysticism can be considered as a vast range that engulfs theoretical and practical and conventional mysticism, but the c ...

as "the most important Arabic inscription of pre-Islamic times" and by Kees Versteegh

Cornelis Henricus Maria "Kees" Versteegh (; born 1947) is a Dutch academic linguist. He served as a professor of Islamic studies and the Arabic language at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands until April 2011.

Versteegh graduated from R ...

as "the most famous Arabic inscription". It is also an important source for the relationships between the Romans and the Arabs in that period.

Differences from Arabic

The inscription is written in the Nabatean Aramaic script, but there are ambiguities, as the script has only 22 signs (some with added annotations), and the Arabic dialect had 28 or 29 consonants. The script has ligatures between some letters that show a transition towards an Arabic script. Some of the terms used in the text are closer to Aramaic than Arabic; for example, it uses the Aramaicpatronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor.

Patronymics are still in use, including mandatory use, in many countries worldwide, alt ...

"b-r", rather than the Arabic term "b-n". However, most of the text is very close to the Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic ( ar, links=no, ٱلْعَرَبِيَّةُ ٱلْفُصْحَىٰ, al-ʿarabīyah al-fuṣḥā) or Quranic Arabic is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notab ...

used in the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

in the 7th century.

Discovery

The inscription was found on 4 April 1901 by two French archaeologists,René Dussaud

René Dussaud (; December 24, 1868 – March 17, 1958) was a French Orientalist, archaeologist, and epigrapher. Among his major works are studies on the religion of the Hittites, the Hurrians, the Phoenicians and the Syriacs. He became curator ...

and Frédéric Macler

Frédéric and Frédérick are the French versions of the common male given name Frederick. They may refer to:

In artistry:

* Frédéric Back, Canadian award-winning animator

* Frédéric Bartholdi, French sculptor

* Frédéric Bazille, Impress ...

, at al-Namara (also Namārah; modern Nimreh

Nimreh ( ar, نمرة, also called Namara) is a village in southern Syria, administratively part of the al-Suwayda Governorate, located northeast of al-Suwayda. It is situated on the northern end of Jabal al-Arab. Nearby localities include Shaqq ...

) near Shahba and Jabal al-Druze in southern Syria, about south of Damascus and northeast Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dara ...

, and east of the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest ...

. The location was near the boundary of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

at the date it was carved, the Limes Arabicus

The ''Limes Arabicus'' was a desert frontier of the Roman Empire, running north from its start in the province of Arabia Petraea. It ran northeast from the Gulf of Aqaba for about at its greatest extent, reaching northern Syria and forming part ...

of the province of Arabia Petraea

Arabia Petraea or Petrea, also known as Rome's Arabian Province ( la, Provincia Arabia; ar, العربية البترائية; grc, Ἐπαρχία Πετραίας Ἀραβίας) or simply Arabia, was a frontier province of the Roman Empi ...

. Al-Namara was later the site of a Roman fort.

History

The inscription is carved in five lines on a block ofbasalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

, which may have been the lintel for a tomb. It is the epitaph of a recently deceased Arab king of the Lakhmids

The Lakhmids ( ar, اللخميون, translit=al-Laḫmiyyūn) referred to in Arabic as al-Manādhirah (, romanized as: ) or Banu Lakhm (, romanized as: ) was an Arab kingdom in Southern Iraq and Eastern Arabia, with al-Hirah as their capital ...

, Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr

Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr ( ar, امرؤ القيس بن عمرو) was the second Lakhmid king. His mother was Maria bint 'Amr, the sister of Ka'b al-Azdi. There is debate on his religious affinity: while Theodor Nöldeke noted that Imru' al-Qays i ...

, and dated securely to AD 328. Imru' al-Qays followed his father 'Amr ibn Adi in using a large army and navy to conquer much of Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and the Arabian peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

from their capital at al-Hirah

Al-Hirah ( ar, الحيرة, translit=al-Ḥīra Middle Persian: ''Hērt'' ) was an ancient city in Mesopotamia located south of what is now Kufa in south-central Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of I ...

. At this time, they were vassals of the Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n Sassanids

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

. Raids on Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

triggered a campaign by Sassanid emperor Shapur II

Shapur II ( pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 ; New Persian: , ''Šāpur'', 309 – 379), also known as Shapur the Great, was the tenth Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran. The longest-reigning monarch in Iranian history, he reigned fo ...

which conquered the Iraqi lands, and Imru' al-Qays retreated to Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

. He moved to Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to seek help from the Roman emperor Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

. Imru' al-Qays converted to Christianity before his death in Syria and was entombed in the Syrian desert

The Syrian Desert ( ar, بادية الشام ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert and steppe covering of the Middle East, including parts of sou ...

. His conversion is mentioned in the Arab history of Hisham Ibn Al-Kalbi

Hishām ibn al-Kalbī ( ar, هشام بن الكلبي), 737 AD – 819 AD/204 AH, also known as Ibn al-Kalbi (), was an Arab historian. His full name was Abu al-Mundhir Hisham ibn Muhammad ibn al-Sa'ib ibn Bishr al-Kalbi. Born in Kufa, he spent ...

, an early ninth century scholar, but Irfan Shahîd

Irfan Arif Shahîd ( ar, عرفان عارف شهيد ; Nazareth, Mandatory Palestine, January 15, 1926 – Washington, D.C., November 9, 2016), born as Erfan Arif Qa'war (), was a scholar in the field of Oriental studies. He was from 1982 unti ...

notes "''there is not a single Christian formula or symbol in the inscription''." While Theodor Nöldeke

Theodor Nöldeke (; born 2 March 1836 – 25 December 1930) was a German orientalist and scholar. His research interests ranged over Old Testament studies, Semitic languages and Arabic, Persian and Syriac literature. Nöldeke translated several ...

argued against a Christian affiliation of Imru' al Qays bin 'Amr, Shahid noted that his Christian belief could be "heretical or of the Manichaean type".

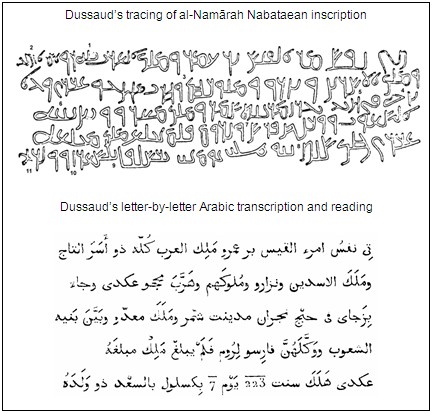

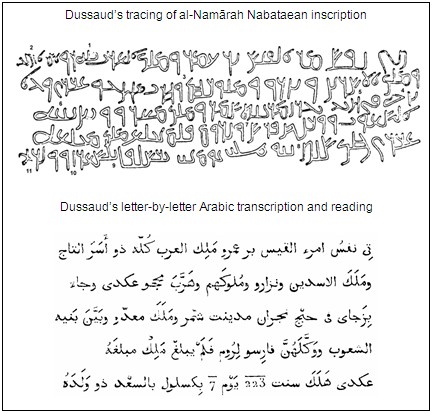

The first tracing and reading of the Namara inscription was published in the beginning of the twentieth century by René Dussaud

René Dussaud (; December 24, 1868 – March 17, 1958) was a French Orientalist, archaeologist, and epigrapher. Among his major works are studies on the religion of the Hittites, the Hurrians, the Phoenicians and the Syriacs. He became curator ...

. According to his reading, the text starts by informing the reader that this inscription was the burial monument of the king, then it introduces him and lists his achievements, and finally announces the date of his death. Many other scholars have re-read and analyzed the language of the inscription over the last century but, despite their slight differences, they all agreed with Dussaud's central viewpoint that the Namara stone was the burial monument of King Imru' al-Qays. In 1985, James A. Bellamy James A. Bellamy (1925 – July 21, 2015) was Professor Emeritus of Arabic Literature at the University of Michigan.

Research

Bellamy has been an important scholar in the textual criticism of the Quran, even being described as the "doyen" of i ...

offered the first significantly different tracing of the inscription since Dussaud, including a breakthrough tracing correction of two highly contested words in the beginning of the third line (pointed out on Dussaud's original tracing figure as words 4 and 5). However, despite Bellamy's new important re-tracings, his Arabic reading fully agreed with the general theme of Dussaud's original reading. Bellamy's widely accepted new translation of the inscription reads: James A. Bellamy, A New Reading of the Namara Inscription, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 105.1 (1985), pp. 31–48.

This is the funerary monument of Imru' al-Qays, son of 'Amr, king of the Arabs, and (?) his title of honor was Master of Asad and Nizar.Below is Bellamy's modern Arabic translation of the Namara inscription, with brief added explanations between parenthesis:

And he subdued the Asadis and they were overwhelmed together with their kings, and he put to flightMadhhij Madhḥij ( ar, مَذْحِج) is a large Qahtanite Arab tribal confederation. It is located in south and central Arabia. This confederation participated in the early Muslim conquests and was a major factor in the conquest of the Persian empire ...thereafter, and came

driving them to the gates ofNajran Najran ( ar, نجران '), is a city in southwestern Saudi Arabia near the border with Yemen. It is the capital of Najran Province. Designated as a new town, Najran is one of the fastest-growing cities in the kingdom; its population has risen fr ..., the city ofShammar The tribe of Shammar ( ar, شَمَّر, Šammar) is a tribal Arab Qahtan confederation, descended from the Yemeni tribe of Tayy as they originated in Yemen before migrating into present day Saudi Arabia, It is the biggest branch of Tayy tribe. I ..., and he subduedMa'add Ma'ad ibn Adnan ( ar, مَعَدّ ٱبْن عَدْنَان, Maʿadd ibn ʿAdnān) is an ancient ancestor of Qusai ibn Kilab and his descendant the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He is featured in ancient Arabic literature. Origin According to t ..., and he dealt gently with the nobles

of the tribes, and appointed them viceroys, and they becamephylarch A phylarch ( el, φύλαρχος, la, phylarchus) is a Greek title meaning "ruler of a tribe", from '' phyle'', "tribe" + ''archein'' "to rule". In Classical Athens, a phylarch was the elected commander of the cavalry provided by each of the ...s for the Romans. And no king has equalled his achievements.

Thereafter he died in the year 223 on the 7th day of Kaslul. Oh the good fortune of those who were his friends!

The mention of the date – the 7th of Kaslul in the year 223 of the Nabatean era of Bostra – securely dates his death to the 7th day of December in AD 328.

Ambiguities in translation

Parts of the translation are uncertain. For example, early translations suggested that Imru' al-Qays was king of ''all'' the Arabs, which seems unlikely after he moved to Syria. It is also not clear whether he campaigned towards Najran while he was based at al-Hirah or after his move to Syria and, in either case, whether he did so alone or with assistance from the Sassanids or the Romans. The inscription is now held by theLouvre Museum

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

in Paris.

References

References

Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads

Jan Retso, pp. 467–

The Arabic Language

By Kees Versteegh, pp. 31–36

Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century

Irfan Shahid, pp. 31–53

The Early Alphabet

John F. Healey, p.54 * http://www.indiana.edu/~arabic/arabic_history.htm

Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet

J. T. Hooker, p.248 {{Louvre Museum 328 works 4th-century inscriptions 1901 archaeological discoveries Ancient Syria Arabic inscriptions Nabataean script History of Saudi Arabia Near East and Middle East antiquities of the Louvre