Music in the movement against apartheid on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The

The apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

regime in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

began in 1948 and lasted until 1994. It involved a system of institutionalized racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

and white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

, and placed all political power in the hands of a white minority. Opposition to apartheid manifested in a variety of ways, including boycotts, non-violent protests, and armed resistance. Music played a large role in the movement against apartheid within South Africa, as well as in international opposition to apartheid. The impacts of songs opposing apartheid included raising awareness, generating support for the movement against apartheid, building unity within this movement, and "presenting an alternative vision of culture in a future democratic South Africa."

The lyrical content and tone of this music reflected the atmosphere that it was composed in. The protest music of the 1950s, soon after apartheid had begun, explicitly addressed peoples' grievances over pass laws

In South Africa, pass laws were a form of internal passport system designed to segregate the population, manage urbanization and allocate migrant labor. Also known as the natives' law, pass laws severely limited the movements of not only blac ...

and forced relocation. Following the Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

in 1960 and the arrest or exile of a number of leaders, songs became more downbeat, while increasing censorship forced them to use subtle and hidden meanings. Songs and performance also allowed people to circumvent the more stringent restrictions on other forms of expression. At the same time, songs played a role in the more militant resistance that began in the 1960s. The Soweto uprising in 1976 led to a renaissance, with songs such as "Soweto Blues

"Soweto Blues" is a protest song written by Hugh Masekela and performed by Miriam Makeba. The song is about the Soweto uprising that occurred in 1976, following the decision by the apartheid government of South Africa to make Afrikaans a medium ...

" encouraging a more direct challenge to the apartheid government. This trend intensified in the 1980s, with racially mixed fusion bands testing the laws of apartheid, before these were dismantled with the release of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

in 1990 and the eventual restoration of majority rule in 1994. Through its history, anti-apartheid music within South Africa faced significant censorship from the government, both directly and via the South African Broadcasting Corporation

The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) is the public broadcaster in South Africa, and provides 19 radio stations ( AM/ FM) as well as six television broadcasts to the general public. It is one of the largest of South Africa's state ...

; additionally, musicians opposing the government faced threats, harassment, and arrests.

Musicians from other countries also participated in the resistance to apartheid, both by releasing music critical of the South African government, and by participating in a cultural boycott of South Africa from 1980 onward. Examples included " Biko" by Peter Gabriel

Peter Brian Gabriel (born 13 February 1950) is an English musician, singer, songwriter, record producer, and activist. He rose to fame as the original lead singer of the progressive rock band Genesis. After leaving Genesis in 1975, he launched ...

, " Sun City" by Artists United Against Apartheid and a concert in honour of Nelson Mandela's 70th birthday. Prominent South African musicians such as Miriam Makeba

Zenzile Miriam Makeba (4 March 1932 – 9 November 2008), nicknamed Mama Africa, was a South African singer, songwriter, actress, and civil rights activist. Associated with musical genres including Afropop, jazz, and world music, she w ...

and Hugh Masekela

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela (4 April 1939 – 23 January 2018) was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who was described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for ...

, forced into exile, also released music critical of apartheid, and this music had a significant impact on Western popular culture, contributing to the "moral outrage" over apartheid. Scholars have stated that anti-apartheid music within South Africa, although it received less attention worldwide, played an equally important role in putting pressure on the South African government.

Background and origins

Racial segregation in South Africa had begun with the arrival of Dutch colonists in South Africa in 1652, and continued through centuries of British rule thereafter. Racial separation increased greatly after the British took complete control over South Africa in the late 19th century, and passed a number of laws early in the 1900s to separate racial groups. The 1923 Natives (Urban Areas) Act forced black South Africans to leave cities unless they were there to work for white people, and excluded them from any role in the government. The system ofapartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

was implemented by the Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cast ...

National Party (NP) after they were voted into power in 1948, and remained in place for 46 years. The white minority held all political power during this time. "Apartheid" meant "separateness" in the Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

language, and involved a brutal system of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

. Black South Africans were compelled to live in poor townships, and were denied basic human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

, based on the idea that South Africa belonged to white people. A prominent figure in the implementation of the apartheid laws was Hendrik Verwoerd

Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd (; 8 September 1901 – 6 September 1966) was a South African politician, a scholar of applied psychology and sociology, and chief editor of '' Die Transvaler'' newspaper. He is commonly regarded as the architect ...

, who was first Minister for Native Affairs and later Prime Minister in the NP government.

There was significant resistance to this system, both within and outside South Africa. Opposition outside the country often took the form of boycotts of South Africa. Within the country, resistance ranged from loosely organised groups to tightly knit ones, and from non-violent protests to armed opposition from the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

. Through this entire process, music played a large role in the resistance. Music had been used in South Africa to protest racial segregation before apartheid began in 1948. The ANC had been founded in 1912, and would begin and end its meetings with its anthem " Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika", an early example of music in the resistance to racial segregation. Another such example was "iLand Act" by R. T. Caluza

R. or r. may refer to:

* ''Reign'', the period of time during which an Emperor, king, queen, etc., is ruler.

* ''Rex (title), Rex'', abbreviated as R., the Latin word meaning King

* ''Regina'', abbreviated as R., the Latin word meaning Queen regna ...

, which protested the Native Land Act

The Natives Land Act, 1913 (subsequently renamed Bantu Land Act, 1913 and Black Land Act, 1913; Act No. 27 of 1913) was an Act of the Parliament of South Africa that was aimed at regulating the acquisition of land.

According to the ''Encyclopæd ...

, and was also adopted as an anthem by the ANC. Commentator Michela Vershbow has written that the music of the movement against apartheid and racial segregation "reflected hewidening gap" between different racial groups and was also an attempt "to communicate across it". Music in South Africa had begun to have explicitly political overtones in the 1930s, as musicians tried to include African elements in their recordings and performances to make political statements. In the 1940s, artists had begun to use music to criticise the state, not directly in response to racial segregation, but as a response to persecution of artists. Artists did not see their music as being directly political: Miriam Makeba

Zenzile Miriam Makeba (4 March 1932 – 9 November 2008), nicknamed Mama Africa, was a South African singer, songwriter, actress, and civil rights activist. Associated with musical genres including Afropop, jazz, and world music, she w ...

would state "people say I sing politics, but what I sing is not politics, it is the truth".

South African music

1950s: Pass laws and resettlement

As the apartheid government became more entrenched in the 1950s, musicians came to see their music as more political in nature, led partly by a campaign of the African National Congress to increase its support. ANC activist and trade unionistVuyisile Mini

Vuyisile Mini (8 April 1920 – 6 November 1964) was a unionist, Umkhonto we Sizwe activist, singer and one of the first African National Congress members to be executed by apartheid South Africa.

Early life

Mini was born in 1920 in Tsomo i ...

was among the pioneers of using music to protest apartheid. He penned "Ndodemnyama we Verwoerd" ("Watch Out, Verwoerd"), in Xhosa. Poet Jeremy Cronin

Jeremy Patrick Cronin (born 12 September 1949) is a South African writer, author, and noted poet. A longtime activist in politics, Cronin is a member of the South African Communist Party and a former member of the National Executive Committee of ...

stated that Mini was the embodiment of the power that songs had built within the protect movement. Mini was arrested in 1963 for "political crimes," and sentenced to death; fellow inmates described him as singing "Ndodemnyama" as he went to the gallows. The song achieved enduring popularity, being sung until well after the apartheid government had collapsed by artists such as Makeba and Afrika Bambaataa

Lance Taylor (born on April 17, 1957), also known as Afrika Bambaataa (), is an American DJ, rapper, and producer from the South Bronx, New York. He is notable for releasing a series of genre-defining electro tracks in the 1980s that influence ...

. Protests songs became generally more popular during the 1950s, as a number of musicians began to voice explicit opposition to apartheid. "uDr. Malan Unomthetho Onzima" (Dr. Malan's Government is Harsh) by Dorothy Masuka

Dorothy Masuka (3 September 1935, in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) – 23 February 2019, in Johannesburg, South Africacarrying passes, which required black citizens to carry a document at all times showing their racial and tribal identity.

In 1954 the NP government passed the Bantu Resettlement Act, which, along with the 1950

The

The

In the early 1970s, the ANC held to the belief that its primary activity was political organising, and that any cultural activity was secondary to this. This belief began to shift with the establishment of the Mayibuye Cultural Ensemble in 1975, and the Amandla Cultural Ensemble later in the 1970s. Mayibuye was established as a growing number of ANC activists argued that cultural events needed to form a part of their work, and could be used to raise awareness of apartheid, gather support, and drive political change. The group was established by ANC activists Barry Feinberg and Ronnie Kasrils, who named it after the slogan ''Mayibuye iAfrika'' (Let Africa Return). The group consisted of several South African performers, and used a mixture of songs, poetry, and narrative in their performance, which described life under the apartheid government and their struggle against it. The songs were often performed in three- or four-part

In the early 1970s, the ANC held to the belief that its primary activity was political organising, and that any cultural activity was secondary to this. This belief began to shift with the establishment of the Mayibuye Cultural Ensemble in 1975, and the Amandla Cultural Ensemble later in the 1970s. Mayibuye was established as a growing number of ANC activists argued that cultural events needed to form a part of their work, and could be used to raise awareness of apartheid, gather support, and drive political change. The group was established by ANC activists Barry Feinberg and Ronnie Kasrils, who named it after the slogan ''Mayibuye iAfrika'' (Let Africa Return). The group consisted of several South African performers, and used a mixture of songs, poetry, and narrative in their performance, which described life under the apartheid government and their struggle against it. The songs were often performed in three- or four-part

The 1980s saw increasing protests against apartheid by black organisations such as the United Democratic Front. Protest music once again became directly critical of the state; examples included "Longile Tabalaza" by Roger Lucey, which attacked the secret police through lyrics about a young man who is arrested by the police and dies in custody. Protesters in the 1980s took to the streets with the intention of making the country "ungovernable", and the music reflected this new militancy. Major protests took place after the inauguration of a "Tri-cameral" parliament (which had separate representation for Indians, Colored people, and white South Africans, but not for black South Africans) in 1984, and in 1985 the government declared a state of emergency. The music became more radical and more urgent as the protests grew in size and number, now frequently invoking and praising the guerrilla movements that had gained steam after the Soweto uprising. The song "Shona Malanga" (Sheila's Day), originally about domestic workers, was adapted to refer to the guerrilla movement. The Toyi-toyi was once again used in confrontations with government forces.

The Afrikaner-dominated government sought to counter these with increasingly frequent states of emergency. During this period, only a few Afrikaners expressed sentiments against apartheid. The Voëlvry movement among Afrikaners began in the 1980s in response with the opening of Shifty Mobile Recording Studio. Voëlvry sought to express opposition to apartheid in

The 1980s saw increasing protests against apartheid by black organisations such as the United Democratic Front. Protest music once again became directly critical of the state; examples included "Longile Tabalaza" by Roger Lucey, which attacked the secret police through lyrics about a young man who is arrested by the police and dies in custody. Protesters in the 1980s took to the streets with the intention of making the country "ungovernable", and the music reflected this new militancy. Major protests took place after the inauguration of a "Tri-cameral" parliament (which had separate representation for Indians, Colored people, and white South Africans, but not for black South Africans) in 1984, and in 1985 the government declared a state of emergency. The music became more radical and more urgent as the protests grew in size and number, now frequently invoking and praising the guerrilla movements that had gained steam after the Soweto uprising. The song "Shona Malanga" (Sheila's Day), originally about domestic workers, was adapted to refer to the guerrilla movement. The Toyi-toyi was once again used in confrontations with government forces.

The Afrikaner-dominated government sought to counter these with increasingly frequent states of emergency. During this period, only a few Afrikaners expressed sentiments against apartheid. The Voëlvry movement among Afrikaners began in the 1980s in response with the opening of Shifty Mobile Recording Studio. Voëlvry sought to express opposition to apartheid in  Among the most popular anti-apartheid songs in South Africa was "

Among the most popular anti-apartheid songs in South Africa was "

Musicians from other countries also participated in resistance to apartheid. Several musicians from Europe and North America refused to perform in South Africa during the apartheid regime: these included

Musicians from other countries also participated in resistance to apartheid. Several musicians from Europe and North America refused to perform in South Africa during the apartheid regime: these included

During the same period as the controversy over "Graceland",

During the same period as the controversy over "Graceland",

A number of South African "Freedom Songs" had musical origins in '' makwaya'', or choir music, which combined elements of Christian hymns with traditional South African musical forms. The songs were often short and repetitive, using a "call-and-response" structure. The music was primarily in indigenous languages such as Xhosa or Zulu, as well as in English. Melodies used in these songs were often very straightforward. Songs in the movement portrayed basic symbols that were important in South Africa—re-purposing them to represent their message of resistance to apartheid. This trend had begun decades previously when South African jazz musicians had added African elements to jazz music adapted from the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. Voëlvry musicians used rock and roll music to represent traditional Afrikaans songs and symbols. Groups affiliated with the

A number of South African "Freedom Songs" had musical origins in '' makwaya'', or choir music, which combined elements of Christian hymns with traditional South African musical forms. The songs were often short and repetitive, using a "call-and-response" structure. The music was primarily in indigenous languages such as Xhosa or Zulu, as well as in English. Melodies used in these songs were often very straightforward. Songs in the movement portrayed basic symbols that were important in South Africa—re-purposing them to represent their message of resistance to apartheid. This trend had begun decades previously when South African jazz musicians had added African elements to jazz music adapted from the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. Voëlvry musicians used rock and roll music to represent traditional Afrikaans songs and symbols. Groups affiliated with the

The apartheid government greatly limited freedom of expression, through censorship, reduced economic freedom, and reduced mobility for black people. However, it did not have the resources to effectively enforce censorship of written and recorded material. The government established the Directorate of Publications in 1974 through the Publications Act, but this body only responded to complaints, and took decisions about banning material that was submitted to it. Less than one hundred pieces of music were formally banned by this body in the 1980s. Thus music and performance played an important role in propagating subversive messages.

However, the government used its control of the

The apartheid government greatly limited freedom of expression, through censorship, reduced economic freedom, and reduced mobility for black people. However, it did not have the resources to effectively enforce censorship of written and recorded material. The government established the Directorate of Publications in 1974 through the Publications Act, but this body only responded to complaints, and took decisions about banning material that was submitted to it. Less than one hundred pieces of music were formally banned by this body in the 1980s. Thus music and performance played an important role in propagating subversive messages.

However, the government used its control of the

Group Areas Act

Group Areas Act was the title of three acts of the Parliament of South Africa enacted under the apartheid government of South Africa. The acts assigned racial groups to different residential and business sections in urban areas in a system o ...

, forcibly moved millions of South Africans into townships in racially segregated zones. This was part of a plan to divide the country into a number of smaller regions, including tiny, impoverished bantustan

A Bantustan (also known as Bantu homeland, black homeland, black state or simply homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa (n ...

s where the black people were to live. In 1955, the settlement of Sophiatown

Sophiatown , also known as Sof'town or Kofifi, is a suburb of Johannesburg, South Africa. Sophiatown was a black cultural hub that was destroyed under apartheid, It produced some of South Africa's most famous writers, musicians, politicians a ...

was destroyed, and its 60,000 inhabitants moved, many to a settlement known as Meadowlands. Sophiatown had been a center of African jazz music prior to the relocation. The move was the inspiration for the writing of the song " Meadowlands", by Strike Vilakezi. As with many other songs of the time, it was popularised both within and outside the country by Miriam Makeba. Makeba's song "Sophiatown is Gone" also referred to the relocation from Sophiatown, as did "Bye Bye Sophiatown" by the Sun Valley Sisters. Music not directly related to the movement was also often harnessed during this period: the South African Communist Party

The South African Communist Party (SACP) is a communist party in South Africa. It was founded in 1921 as the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), tactically dissolved itself in 1950 in the face of being declared illegal by the governing N ...

would use such music for its fundraising dances, and the song "Udumo Lwamaphoyisa" (A Strong Police Force) was sung by lookouts to provide warnings of police presence and liquor raids.

1960s: Sharpeville massacre and militancy

The

The Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

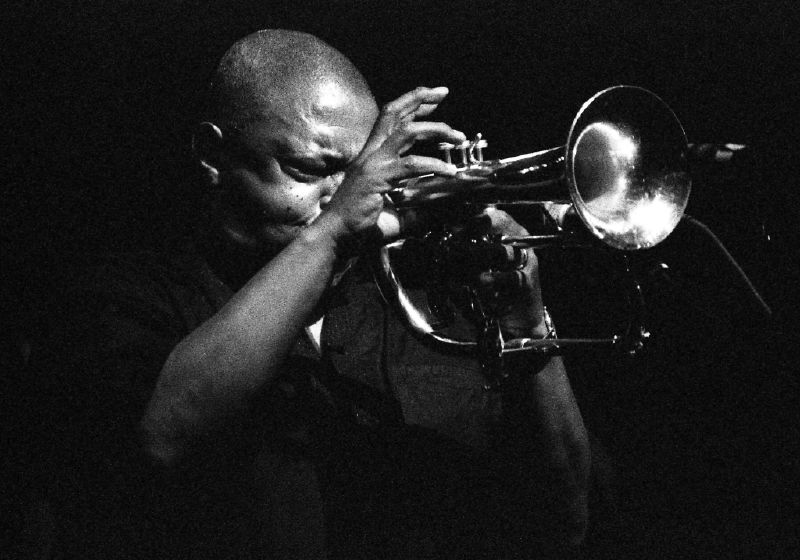

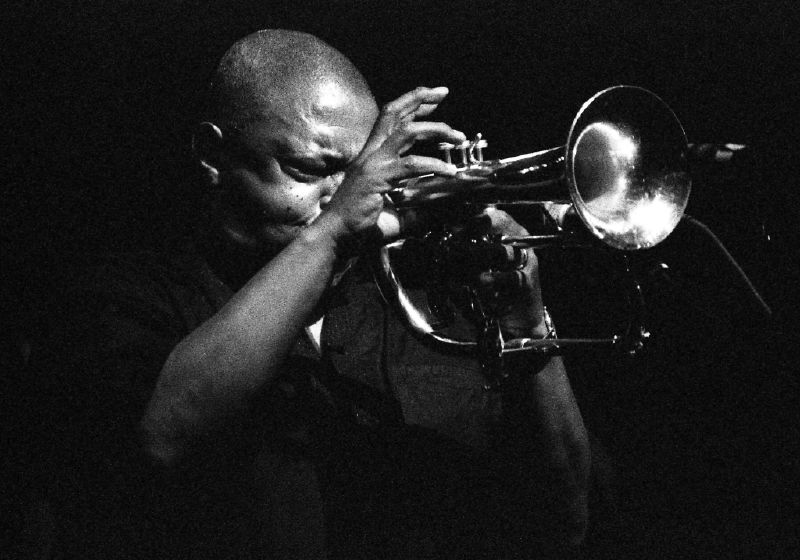

occurred on 21 March 1960, and in its aftermath apartheid was intensified and political dissent increasingly suppressed. The ANC and the Pan Africanist Conference were banned, and 169 black leaders were tried for treason. A number of musicians, including Makeba, Hugh Masekela

Hugh Ramapolo Masekela (4 April 1939 – 23 January 2018) was a South African trumpeter, flugelhornist, cornetist, singer and composer who was described as "the father of South African jazz". Masekela was known for his jazz compositions and for ...

, Abdullah Ibrahim

Abdullah Ibrahim (born Adolph Johannes Brand on 9 October 1934 and formerly known as Dollar Brand) is a South African pianist and composer. His music reflects many of the musical influences of his childhood in the multicultural port areas of Cap ...

, Jonas Gwangwa

Jonas Mosa Gwangwa (19 October 1937 – 23 January 2021) was a South African jazz musician, songwriter and producer. He was an important figure in South African jazz for over 40 years.

Career

Gwangwa was born in Orlando East, Soweto. He firs ...

, Chris McGregor

Christopher McGregor (24 December 1936 – 26 May 1990) was a South African jazz pianist, bandleader and composer born in Somerset West, South Africa.

Early influences

McGregor grew up in the then Transkei (now part of the Eastern Cape Provin ...

, and Kippie Moeketsie went into exile. Some, such as Makeba and Masekela, began using their music to raise awareness of apartheid. Those musicians that remained found their activities constrained. The new townships that black people had been moved to lacked facilities for recreation, and large gatherings of people were banned. The South African Broadcasting Corporation tightened its broadcasting guidelines, preventing "subversive" music from being aired. A recording by Masuka referring to the killing of Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

led to a raid on her studio and her being declared a wanted individual, preventing her from living in South Africa for the next 30 years.

The new townships that black people were moved to, despite their "dreary" nature, also inspired politically charged music, a trend which continued into the 1970s. " In Soweto" by The Minerals has been described as an "infectious celebration of a place" and of the ability of its residents to build a community there. Yakhal' Inkhomo ("The Bellowing of the Bull", 1968), by Winston "Mankunku" Ngozi, was a jazz anthem that also expressed the political energy of the period. Theatrical performances incorporating music were also a feature of the townships, often narrowly avoiding censorship. The cultural isolation forced by apartheid led to artists within South Africa creating local adaptations of popular genres, including rock music, soul, and jazz.

As the government became increasingly harsh in its response to growing protests, the resistance shifted from being completely non-violent towards armed action. Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders founded the uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), a militant wing of the ANC, which began a campaign of sabotage. During this period, music was often referred to as a "weapon of struggle." Among MK members in training camps, a song called "Sobashiy'abazali" ("We Will Leave Our Parents") became very popular, invoking as it did the pain of leaving their homes. The Toyi-toyi Toyi-toyi is a Southern African dance used in political protests in South Africa.

Toyi-toyi could begin as the stomping of feet and spontaneous chanting during protests that could include political slogans or songs, either improvised or previously ...

chant also became popular during this period, and was frequently used to generate a sense of power among large groups to intimidate government troops.

1970s: ANC cultural groups and Soweto uprising

In the early 1970s, the ANC held to the belief that its primary activity was political organising, and that any cultural activity was secondary to this. This belief began to shift with the establishment of the Mayibuye Cultural Ensemble in 1975, and the Amandla Cultural Ensemble later in the 1970s. Mayibuye was established as a growing number of ANC activists argued that cultural events needed to form a part of their work, and could be used to raise awareness of apartheid, gather support, and drive political change. The group was established by ANC activists Barry Feinberg and Ronnie Kasrils, who named it after the slogan ''Mayibuye iAfrika'' (Let Africa Return). The group consisted of several South African performers, and used a mixture of songs, poetry, and narrative in their performance, which described life under the apartheid government and their struggle against it. The songs were often performed in three- or four-part

In the early 1970s, the ANC held to the belief that its primary activity was political organising, and that any cultural activity was secondary to this. This belief began to shift with the establishment of the Mayibuye Cultural Ensemble in 1975, and the Amandla Cultural Ensemble later in the 1970s. Mayibuye was established as a growing number of ANC activists argued that cultural events needed to form a part of their work, and could be used to raise awareness of apartheid, gather support, and drive political change. The group was established by ANC activists Barry Feinberg and Ronnie Kasrils, who named it after the slogan ''Mayibuye iAfrika'' (Let Africa Return). The group consisted of several South African performers, and used a mixture of songs, poetry, and narrative in their performance, which described life under the apartheid government and their struggle against it. The songs were often performed in three- or four-part harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. Howeve ...

. The group performed more than 200 times across Europe, and were seen as the cultural arm of the ANC. The group experienced personal and organisational difficulties, and disbanded in 1980.

In 1976 the government of South Africa decided to implement the use of Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

as the medium of instruction in all schools instead of English. In response, high school students began a series of protests that came to be known as the Soweto Uprising. 15,000–20,000 students took part; the police, caught unprepared, opened fire on the protesting children. 700 people were estimated to have been killed, and over a thousand injured. The killings sparked off several months of rioting in the Soweto townships, and the protests became an important moment for the anti-Apartheid movement. Hugh Masekela wrote Soweto Blues

"Soweto Blues" is a protest song written by Hugh Masekela and performed by Miriam Makeba. The song is about the Soweto uprising that occurred in 1976, following the decision by the apartheid government of South Africa to make Afrikaans a medium ...

in response to the massacre, and the song was performed by Miriam Makeba, becoming a standard part of Makeba's live performances for many years. "Soweto Blues" was one of many melancholic songs composed by Masekela during this period that expressed his support of the anti-apartheid struggle, along with "Been Gone Far Too Long," "Mama," and "The Coal Train." Songs written after the Soweto uprising were generally political in nature, but used hidden meaning to avoid suppression, especially as the movement against apartheid gained momentum. A song by the band Juluka

Juluka was a South African music band formed in 1969 by Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu. means "sweat" in Zulu, and was the name of a bull owned by Mchunu. The band was closely associated with the mass movement against apartheid.

History

At th ...

used a metaphor of fighting bulls to suggest the fall of apartheid. Many songs of this period became so widely known that their lyrics were frequently altered and adapted depending on the circumstances, making their authorship collective. Pianist Abdullah Ibrahim used purely musical techniques to convey subversive messages, by incorporating melodies from freedom songs into his improvisations. Ibrahim also composed "Mannenberg

"Mannenberg" is a Cape jazz song by South African musician Abdullah Ibrahim, first recorded in 1974. Driven into exile by the apartheid government, Ibrahim had been living in Europe and the United States during the 1960s and '70s, making brief ...

", described as the "most powerful anthem of the struggle in the 1980s", which had no lyrics but drew on a number of aspects of black South African culture, including church music, jazz, ''marabi'', and blues, to create a piece that conveyed a sense of freedom and cultural identity.

The importance that the anti-apartheid movement among South African exiles increased in the late 1970s, driven partly by the activities of Mayibuye. The Amandla Cultural Ensemble drew together among militant ANC activities living in Angola and elsewhere in this period, influenced by Mayibuye, as well as the World Black Festival of Arts and Culture that was held in Nigeria in 1977. As with Mayibuye, the group tried to use their performances to raise awareness and generate support for the ANC; however, they relied chiefly on new material composed by their own members, such as Jonas Gwangwa

Jonas Mosa Gwangwa (19 October 1937 – 23 January 2021) was a South African jazz musician, songwriter and producer. He was an important figure in South African jazz for over 40 years.

Career

Gwangwa was born in Orlando East, Soweto. He firs ...

. Popular songs performed by the group were selected for or adapted to a militaristic and faster tone and tempo; at the same time, the tenor of the groups performance tended to be more affirmative, and less antagonistic and sarcastic, than that of Mayibuye. Members often struggled to balance their commitments to the ensemble with their military activities, which were often seen as their primary job; some, such as Nomkhosi Mini, daughter of Vuyisile Mini, were killed in military action while they were performing with Amandla. Such artists also faced pressure to use their performance solely in the service of the political movement, without monetary reward. Amandla had carefully crafted performances of music and theater, with a much larger ensemble than Mayibuye, which included a jazz band. The influence of these groups would last beyond the 1970s: a "Culture and Resistance" conference was held in Botswana in 1982, and the ANC established a "Department of Arts and Culture" in 1985.

1980s: Direct confrontation

The 1980s saw increasing protests against apartheid by black organisations such as the United Democratic Front. Protest music once again became directly critical of the state; examples included "Longile Tabalaza" by Roger Lucey, which attacked the secret police through lyrics about a young man who is arrested by the police and dies in custody. Protesters in the 1980s took to the streets with the intention of making the country "ungovernable", and the music reflected this new militancy. Major protests took place after the inauguration of a "Tri-cameral" parliament (which had separate representation for Indians, Colored people, and white South Africans, but not for black South Africans) in 1984, and in 1985 the government declared a state of emergency. The music became more radical and more urgent as the protests grew in size and number, now frequently invoking and praising the guerrilla movements that had gained steam after the Soweto uprising. The song "Shona Malanga" (Sheila's Day), originally about domestic workers, was adapted to refer to the guerrilla movement. The Toyi-toyi was once again used in confrontations with government forces.

The Afrikaner-dominated government sought to counter these with increasingly frequent states of emergency. During this period, only a few Afrikaners expressed sentiments against apartheid. The Voëlvry movement among Afrikaners began in the 1980s in response with the opening of Shifty Mobile Recording Studio. Voëlvry sought to express opposition to apartheid in

The 1980s saw increasing protests against apartheid by black organisations such as the United Democratic Front. Protest music once again became directly critical of the state; examples included "Longile Tabalaza" by Roger Lucey, which attacked the secret police through lyrics about a young man who is arrested by the police and dies in custody. Protesters in the 1980s took to the streets with the intention of making the country "ungovernable", and the music reflected this new militancy. Major protests took place after the inauguration of a "Tri-cameral" parliament (which had separate representation for Indians, Colored people, and white South Africans, but not for black South Africans) in 1984, and in 1985 the government declared a state of emergency. The music became more radical and more urgent as the protests grew in size and number, now frequently invoking and praising the guerrilla movements that had gained steam after the Soweto uprising. The song "Shona Malanga" (Sheila's Day), originally about domestic workers, was adapted to refer to the guerrilla movement. The Toyi-toyi was once again used in confrontations with government forces.

The Afrikaner-dominated government sought to counter these with increasingly frequent states of emergency. During this period, only a few Afrikaners expressed sentiments against apartheid. The Voëlvry movement among Afrikaners began in the 1980s in response with the opening of Shifty Mobile Recording Studio. Voëlvry sought to express opposition to apartheid in Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

. The goal of Voëlvry musicians was to persuade Afrikaner youth of the changes their culture had to undergo to achieve racial equality. Prominent members in this phenomenon were Ralph Rabie, under the stage name Johannes Kerkorrel

Johannes Kerkorrel (27 March 1960 – 12 November 2002), born Ralph John Rabie, was a South African singer-songwriter, journalist and playwright.

Career

Rabie, who was born in Johannesburg, worked as a journalist for the Afrikaans newspapers '' ...

, Andre du Toit, and Bernoldus Niemand

James Phillips (22 January 1959 – 31 July 1995) was a South African rock vocalist, songwriter, and performer. He was best known for his rebellious and satirical political music that spoke out against the South African government during Apa ...

. Racially integrated bands playing various kinds of fusion became more common as the 1980s progressed; their audiences came from across racial lines, itself a subversive act, as racial segregation was still embedded in the law. The racially mixed Juluka, led by Johnny Clegg

Jonathan Paul Clegg, (7 June 195316 July 2019) was a South African musician, singer-songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and anti-apartheid activist, some of whose work was in musicology focused on the music of indigenous South African people ...

, remained popular through the 1970s and early 1980s. The government tried to harness this popularity by sponsoring a multi-lingual song titled "Together We Will Build a Brighter Future," but the release, during a period of great political unrest, caused further anger at the government, and protests forced the song to be withdrawn before commercial sales were made.

Among the most popular anti-apartheid songs in South Africa was "

Among the most popular anti-apartheid songs in South Africa was "Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela)

"Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela)", also known as "Bring Him Back Home", is an anthemic anti-apartheid protest song written by South African musician Hugh Masekela. It was released as the first track of his 1987 album '' Tomorrow''. It was ...

" by Hugh Masekela. Nelson Mandela was a great fan of Masekela's music, and on Masekela's birthday in 1985, smuggled out a letter to him expressing his good wishes. Masekela was inspired to write "Bring Him Back Home" in response. Sam Raditlhalo writes that the reception of Mandela's letter, and the writing of Bring Him Back Home, marked Masekela being labelled an anti-apartheid activist. Mandela was also invoked in " Black President" by Brenda Fassie; composed in 1988, this song explicitly invoked Mandela's eventual presidency. Mandela was released in 1990 and went on a post-freedom tour of North America with Winnie. In Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, he danced as "Bring Him Back Home" was played after his speech. Mandela's release triggered a number of celebratory songs. These included a "peace song", composed by Chicco Twala, and featuring a number of artists, including Masekela, Fassie, and Yvonne Chaka Chaka

Yvonne Chaka Chaka (born Yvonne Machaka on 18 March 1965) is a South African singer, songwriter, actress, entrepreneur, humanitarian and teacher. Dubbed the "Princess of Africa" (a name she received after a 1990 tour), Chaka Chaka has been at t ...

. The proceeds from this piece went to the "Victims of Violence" fund. Majority rule was restored to South Africa in 1994, ending the period of apartheid.

Outside South Africa

Musicians from other countries also participated in resistance to apartheid. Several musicians from Europe and North America refused to perform in South Africa during the apartheid regime: these included

Musicians from other countries also participated in resistance to apartheid. Several musicians from Europe and North America refused to perform in South Africa during the apartheid regime: these included The Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

, The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically dr ...

, and the Walker Brothers. After the Sharpeville massacre

The Sharpeville massacre occurred on 21 March 1960 at the police station in the township of Sharpeville in the then Transvaal Province of the then Union of South Africa (today part of Gauteng). After demonstrating against pass laws, a crowd ...

in 1960, the Musicians' Union in the UK announced a boycott of the government. The first South African activist to receive widespread attention outside South Africa was Steve Biko

Bantu Stephen Biko (18 December 1946 – 12 September 1977) was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he was at the forefront of a grassroots anti-apartheid campaign known ...

when he died in police custody in 1977. His death inspired a number of songs from artists outside the country, including from Tom Paxton and Peter Hammill

Peter Joseph Andrew Hammill (born 5 November 1948) is an English musician and recording artist. He was a founder member of the progressive rock band Van der Graaf Generator. Best known as a singer/songwriter, he also plays guitar and piano and ...

. The most famous of these was the song " Biko" by Peter Gabriel

Peter Brian Gabriel (born 13 February 1950) is an English musician, singer, songwriter, record producer, and activist. He rose to fame as the original lead singer of the progressive rock band Genesis. After leaving Genesis in 1975, he launched ...

. U2 lead singer Bono

Paul David Hewson (born 10 May 1960), known by his stage name Bono (), is an Irish singer-songwriter, activist, and philanthropist. He is the lead vocalist and primary lyricist of the rock band U2.

Born and raised in Dublin, he attended ...

was among the people who said that the song was the first time he had heard about apartheid. Musicians from other parts of Africa also wrote songs to support the movement; Nigeria's Sonny Okosun

Sonny Okosun (1 January 1947 – 24 May 2008) was a Nigerian musician, who was known as the leader of the Ozzidi band. He named his band Ozzidi after a renowned Ijaw river god, but to Okosun the meaning was "there is a message". His surname is ...

drew attention to apartheid with songs such as "Fire in Soweto", described by the ''Los Angeles Times'' as an "incendiary reggae jam".

Cultural boycott

A cultural boycott of the apartheid government had been suggested in 1954 by English Anglican bishopTrevor Huddleston

Ernest Urban Trevor Huddleston (15 June 191320 April 1998) was an English Anglican bishop. He was the Bishop of Stepney in London before becoming the second Archbishop of the Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean. He was best known for ...

. In 1968 the United Nations passed a resolution asking members to cut any "cultural, educational, and sporting ties with the racist regime", thereby bringing pressure to bear on musicians and other performers to avoid playing in South Africa. In 1980, the UN passed a resolution allowing a cultural boycott of South Africa. The resolution named Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

, and his profile was raised further by the ANC deciding to focus its campaign on him in 1982, 20 years after he had been imprisoned. In 1983, Special AKA

The Specials, also known as The Special AKA, are an English 2 tone and ska revival band formed in 1977 in Coventry. After some early changes, the first stable lineup of the group consisted of Terry Hall and Neville Staple on vocals, Lynval ...

released their song "Free Nelson Mandela

"Nelson Mandela" (known in some versions as "Free Nelson Mandela") is a song written by British musician Jerry Dammers, and performed by band The Special A.K.A. – with lead vocal by Stan Campbell – released on the single "Nelson Mandela"/" ...

", an optimistic finale to their debut album, which was generally sombre. The song was produced by Elvis Costello

Declan Patrick MacManus OBE (born 25 August 1954), known professionally as Elvis Costello, is an English singer-songwriter and record producer. He has won multiple awards in his career, including a Grammy Award in 2020, and has twice been nom ...

, and had a backing chorus composed of members of the Specials and the Beat, which created a mood of "joyous solidarity". The lyrics to the song were written by Jerry Dammers

Jeremy David Hounsell Dammers GCOT (born 22 May 1955) is a British musician who was a founder, keyboard player and primary songwriter of the Coventry-based ska band The Specials (also known as The Special A.K.A.) and later The Spatial AKA Orche ...

. Dammers also founded the British branch of the organisation Artists United Against Apartheid. The song was quickly embraced by the movement against apartheid. It was used by the UN and the ANC, and demonstrators would frequently sing it during marches and rallies. The chorus was catchy and straightforward, making it easy to remember. Dammers utilised the association with the anti-apartheid movement to popularise the song, by putting an image of Mandela on the front of the cover for the album, and placing information about the apartheid regime on the back.

In the late 1980s, Paul Simon

Paul Frederic Simon (born October 13, 1941) is an American musician, singer, songwriter and actor whose career has spanned six decades. He is one of the most acclaimed songwriters in popular music, both as a solo artist and as half of folk roc ...

caused controversy when he chose to record his album '' Graceland'' in South Africa, along with a number of Black African musicians. He received sharp criticism for breaking the cultural boycott. In 1987 he claimed to have received clearance from the ANC: however, he was contradicted by Dali Tambo, the son of ANC president Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and revolutionary who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography

Higher education

Oliv ...

, and the founder of Artists United Against Apartheid. As a way out of the fracas, Hugh Masekela, who had known Simon for many years, proposed a joint musical tour, which would include songs from ''Graceland'' as well as from black South African artists. Miriam Makeba was among the musicians featured on the Graceland Tour. Masekela justified the tour saying that the cultural boycott had led to a "lack of growth" in South African music. However, when the group played in the UK at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

, there were protests outside, in which Dammers participated, along with Billy Bragg

Stephen William Bragg (born 20 December 1957) is an English singer-songwriter and left-wing activist. His music blends elements of folk music, punk rock and protest songs, with lyrics that mostly span political or romantic themes. His music i ...

and Paul Weller

Paul John Weller (born John William Weller; 25 May 1958) is an English singer-songwriter and musician. Weller achieved fame with the punk rock/ new wave/mod revival band the Jam (1972–1982). He had further success with the blue-eyed soul mu ...

. Songs performed on the tour included "Soweto Blues", sung by Makeba, along with many other anti-apartheid songs.

Sun City and aftermath

During the same period as the controversy over "Graceland",

During the same period as the controversy over "Graceland", Steven van Zandt

Steven Van Zandt (né Lento; born November 22, 1950), also known as Little Steven or Miami Steve, is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and actor. He is a member of Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band, in which he plays guitar and mandoli ...

, upset by the fact that artists from Europe and North America were willing to perform in Sun City, a whites-only luxury resort in the "homeland" of Bophutatswana, persuaded artists including Bono, Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen (born September 23, 1949) is an American singer and songwriter. He has released 21 studio albums, most of which feature his backing band, the E Street Band. Originally from the Jersey Shore, he is an originato ...

, and Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of music ...

, to come together to record the single "Sun City", which was released in 1985. The single achieved its aim of stigmatising the resort. The album was described as the "most political of all of the charity rock albums of the 1980s". "Sun City" was explicitly critical of the foreign policy of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, stating that he had failed to take firm action against apartheid. As a result, only about half of American radio stations played "Sun City." Meanwhile, "Sun City" was a major success in countries where there was little or no radio station resistance to the record or its messages, reaching No. 4 in Australia, No. 10 in Canada and No. 21 in the UK.

A number of prominent anti-apartheid songs were released in the years that followed. Stevie Wonder

Stevland Hardaway Morris ( Judkins; May 13, 1950), known professionally as Stevie Wonder, is an American singer-songwriter, who is credited as a pioneer and influence by musicians across a range of genres that include rhythm and blues, pop, s ...

released " It's Wrong", and was also arrested for protesting against apartheid outside the South African embassy in Washington, D.C. A song popular with younger audiences was " I've Never Met a Nice South African" by Spitting Image

''Spitting Image'' is a television in the United Kingdom, British satire, satirical television puppet show, created by Peter Fluck, Roger Law and Martin Lambie-Nairn. First broadcast in 1984, the series was produced by 'Spitting Image Productio ...

, which released the song as a b-side

The A-side and B-side are the two sides of phonograph records and cassettes; these terms have often been printed on the labels of two-sided music recordings. The A-side usually features a recording that its artist, producer, or record compan ...

to their successful " The Chicken Song". Eddy Grant, a Guyanese-British reggae

Reggae () is a music genre that originated in Jamaica in the late 1960s. The term also denotes the modern popular music of Jamaica and its diaspora. A 1968 single by Toots and the Maytals, " Do the Reggay" was the first popular song to use ...

musician, released " Gimme Hope Jo'anna" (Jo'Anna being Johannesburg). Other performers released music which referenced Steve Biko. Labi Siffre's "(Something Inside) So Strong

"(Something Inside) So Strong" is a song written and recorded by British singer-songwriter Labi Siffre. Released as a single in 1987, it was one of the biggest successes of his career, peaking at number four on the UK Singles Chart.

The song was ...

", a UK top 5 hit single in 1987, was adopted as an anti-apartheid anthem.

In 1988, Dammers and Jim Kerr

James Kerr (born 9 July 1959) is a Scottish singer and the lead singer of the rock band Simple Minds, becoming best known internationally for "Don't You (Forget About Me)" (1985), which topped the ''Billboard'' Hot 100 in the United States. Ot ...

, the vocalist of Simple Minds

Simple Minds are a Scottish rock band formed in Glasgow in 1977. They have released a string of hit singles, becoming best known internationally for " Don't You (Forget About Me)" (1985), which topped the '' Billboard'' Hot 100 in the United ...

, organised a concert in honour of Mandela's 70th birthday. The concert was held at Wembley Stadium

Wembley Stadium (branded as Wembley Stadium connected by EE for sponsorship reasons) is a football stadium in Wembley, London. It opened in 2007 on the site of the Wembley Stadium (1923), original Wembley Stadium, which was demolished from 200 ...

, and ended with the songs "Biko," "Sun City", and "Bring Him Back Home". Dammers and Simple Minds also performed their own anti-apartheid songs: "Free Nelson Mandela" and " Mandela Day", respectively. Other acts performing at the concert included Stevie Wonder, Whitney Houston

Whitney Elizabeth Houston (August 9, 1963 – February 11, 2012) was an American singer and actress. Nicknamed "Honorific nicknames in popular music, The Voice", she is Whitney Houston albums discography, one of the bestselling music artists ...

, Sting

Sting may refer to:

* Stinger or sting, a structure of an animal to inject venom, or the injury produced by a stinger

* Irritating hairs or prickles of a stinging plant, or the plant itself

Fictional characters and entities

* Sting (Middle-earth ...

, Salt-N-Pepa

Salt-N-Pepa (also stylized as Salt 'N' Pepa or Salt 'N Pepa) is an American hip-hop group formed in New York City in 1985, that comprised Salt (Cheryl James), Pepa (Sandra Denton), and DJ Spinderella (Deidra Roper). Their debut album, '' Hot, ...

, Dire Straits

Dire Straits were a British rock band formed in London in 1977 by Mark Knopfler (lead vocals and lead guitar), David Knopfler (rhythm guitar and backing vocals), John Illsley (bass guitar and backing vocals) and Pick Withers (drums and per ...

and Eurythmics

Eurythmics were a British Pop music, pop duo consisting of Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart (musician and producer), Dave Stewart. They were both previously in The Tourists, a band which broke up in 1980. The duo released their first studio alb ...

. The event was broadcast to a TV audience of approximately 600 million people. Political aspects of the concert were heavily censored in the United States by the Fox television network, which rebranded it as "Freedomfest". The use of music to raise awareness about apartheid paid off: a survey after the concert found that among people aged between 16 and 24, three-fourths knew of Nelson Mandela, and supported his release from prison. Although the cultural boycott had succeeded in isolating the apartheid government culturally, it also affected musicians who had worked against apartheid within South Africa; thus Johnny Clegg

Jonathan Paul Clegg, (7 June 195316 July 2019) was a South African musician, singer-songwriter, dancer, anthropologist and anti-apartheid activist, some of whose work was in musicology focused on the music of indigenous South African people ...

and Savuka

Savuka, occasionally referred to as Johnny Clegg & Savuka, was a multi-racial South African band formed in 1986 by Johnny Clegg after the disbanding of Juluka. Savuka's music blended traditional Zulu musical influences with Celtic music and r ...

were forbidden from playing at the concert.

Lyrical and musical themes

The lyrics of anti-apartheid protest music often used subversive meanings hidden under innocuous lyrics, partially as a consequence of the censorship that they experienced. Purely musical techniques were also used to convey meaning. The tendency to use hidden meaning increased as the government grew less tolerant from the 1950s to the 1980s. Popular protest songs of the 1950s often directly addressed politicians. "Ndodemnyama we Verwoerd" by Mini told Hendrik Verwoerd "Naants'indod'emnyama, Verwoerd bhasobha" (beware of the advancing blacks), while a song referring to pass laws in 1956 included the phrase "Hey Strydom, Wathint'a bafazi, way ithint'imbodoko uzaKufa" (Strydom, now that you have touched the women, you have struck a rock, you have dislodged a boulder, and you will be crushed). Following the Sharpeville massacre songs became less directly critical of the government, and more mournful. "Thina Sizwe" included references to stolen land, was described as depicting emotional desolation, while "Senzeni Na" (what have we done) achieved the same effect by repeating that phrase a number of times. Some musicians adapted innocuous popular tunes and modified their lyrics, thereby avoiding the censors. The Soweto uprising marked a turning point in the movement, as songs written in the 1980s again became more direct, with the appearance of musicians such as Lucey, who "believed in an in‐your‐face, tell‐it‐like‐it‐is approach". Lyrics from this period included calls such as "They are lying to themselves. Arresting us, killing us, won't work. We'll still fight for our land," and "The whites don't negotiate with us, so let's fight". A number of South African "Freedom Songs" had musical origins in '' makwaya'', or choir music, which combined elements of Christian hymns with traditional South African musical forms. The songs were often short and repetitive, using a "call-and-response" structure. The music was primarily in indigenous languages such as Xhosa or Zulu, as well as in English. Melodies used in these songs were often very straightforward. Songs in the movement portrayed basic symbols that were important in South Africa—re-purposing them to represent their message of resistance to apartheid. This trend had begun decades previously when South African jazz musicians had added African elements to jazz music adapted from the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. Voëlvry musicians used rock and roll music to represent traditional Afrikaans songs and symbols. Groups affiliated with the

A number of South African "Freedom Songs" had musical origins in '' makwaya'', or choir music, which combined elements of Christian hymns with traditional South African musical forms. The songs were often short and repetitive, using a "call-and-response" structure. The music was primarily in indigenous languages such as Xhosa or Zulu, as well as in English. Melodies used in these songs were often very straightforward. Songs in the movement portrayed basic symbols that were important in South Africa—re-purposing them to represent their message of resistance to apartheid. This trend had begun decades previously when South African jazz musicians had added African elements to jazz music adapted from the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. Voëlvry musicians used rock and roll music to represent traditional Afrikaans songs and symbols. Groups affiliated with the Black Consciousness

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-Apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Afri ...

movement also began incorporating traditional material into their music: the jazz-fusion group Malombo, for example, used traditional rhythms of the Venda people

The Venḓa (VhaVenḓa or Vhangona) are a Southern African Bantu people living mostly near the South African- Zimbabwean border.

The history of the Venda starts from the Kingdom of Mapungubwe (9th Century) where King Shiriyadenga was

the ...

to communicate pride in African culture, often with music that was not explicitly political. While musicians such as Makeba, performing outside South Africa, felt an obligation to write political lyrics, musicians within the country often held that there was no divide between revolutionary music and, for instance, love songs, because the struggle of living a normal life was also a political one. Vusi Mahlasela would write in 1991: "So who are they who say no more love poems now? I want to sing a song of love for that woman who jumped fences pregnant and still gave birth to a healthy child."

The lyrical and musical tone of protest songs varied with the circumstances they were written and composed in. The lyrics of "Bring Him Back Home", for example, mention Mandela "walking hand in hand with Winnie Mandela

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela (born Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela; 26 September 1936 – 2 April 2018), also known as Winnie Mandela, was a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician, and the second wife of Nelson Mandela. She ser ...

," his wife at the time. The melody used in the song is upbeat and anthem-like. It employs a series of trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

riffs by Masekela, supported by grand series of chords. Music review website AllMusic

AllMusic (previously known as All Music Guide and AMG) is an American online database, online music database. It catalogs more than three million album entries and 30 million tracks, as well as information on Musical artist, musicians and Music ...

describes the melody as "filled with the sense of camaraderie and celebration that are referred to in the lyrics. The vocal choir during the joyous chorus is extremely moving and life affirming". In contrast, the lyrics of "Soweto Blues" refer to the children's protests and the resulting massacre in the Soweto uprising. A review stated that the song had "searingly righteous lyrics" that "cut to the bone." Musically, the song has a background of mbaqanga

Mbaqanga () is a style of South African music with rural Zulu roots that continues to influence musicians worldwide today. The style originated in the early 1960s.

History

Historically, laws such as the Land Act of 1913 to the Group Areas Ac ...

guitar, bass

Bass or Basses may refer to:

Fish

* Bass (fish), various saltwater and freshwater species

Music

* Bass (sound), describing low-frequency sound or one of several instruments in the bass range:

** Bass (instrument), including:

** Acoustic bass gui ...

, and multi-grooved percussion. Makeba uses this as a platform for vocals that are half-sung and half-spoken, similar to blues music

Blues is a music genre and musical form which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues incorporated spirituals, work songs, field hollers, shouts, chants, and rhymed simple narrative ballads from the Afric ...

.

Censorship and resistance

The apartheid government greatly limited freedom of expression, through censorship, reduced economic freedom, and reduced mobility for black people. However, it did not have the resources to effectively enforce censorship of written and recorded material. The government established the Directorate of Publications in 1974 through the Publications Act, but this body only responded to complaints, and took decisions about banning material that was submitted to it. Less than one hundred pieces of music were formally banned by this body in the 1980s. Thus music and performance played an important role in propagating subversive messages.

However, the government used its control of the

The apartheid government greatly limited freedom of expression, through censorship, reduced economic freedom, and reduced mobility for black people. However, it did not have the resources to effectively enforce censorship of written and recorded material. The government established the Directorate of Publications in 1974 through the Publications Act, but this body only responded to complaints, and took decisions about banning material that was submitted to it. Less than one hundred pieces of music were formally banned by this body in the 1980s. Thus music and performance played an important role in propagating subversive messages.

However, the government used its control of the South African Broadcasting Corporation

The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) is the public broadcaster in South Africa, and provides 19 radio stations ( AM/ FM) as well as six television broadcasts to the general public. It is one of the largest of South Africa's state ...

to prevent "undesirable" songs from being played (which included political or rebellious music, and music with "blasphemous" or overtly sexual lyrics), and to enforce its ideal of a cultural separation between racial groups, in addition to physical separation it had created. Radio and television broadcasts were area-specific such that members of different racial groups received different programs, and music was selected keeping the ideology of the government in mind. Music that used slang or more than one language faced censorship. Artists were required to submit both their lyrics and their music to be scrutinised by the SABC committee, which banned thousands of songs. For instance, Shifty Records, from the time of its establishment in 1982 until the end of the 1980s, had 25 music albums and seven singles banned by the Directorate of Publications because of political content and a further 16 for other reasons such as blasphemy and obscenity.

As a result of the practices of the SABC, record companies began putting pressure on their artists to avoid controversial songs, and often also made changes to songs they were releasing. Individuals were expected to racially segregate their musical choices as well: mixed-race bands were sometimes forced to play with some members behind a curtain, and people who listened to music composed by members of a different race faced government suspicion. Many black musicians faced harassment from the police; Jonas Gwangwa stated that performers were often stopped and required to explain their presence in "white" localities. Black musicians were forbidden from playing at venues when alcohol was sold, and performers were required to have an extra "night pass" to be able to work in the evenings. Further restrictions were placed by the government each time it declared a state of emergency, and internal security legislation was also used to ban material. Music from artists outside the country was also targeted by the censors; all songs by The Beatles were banned in the 1960s, and Stevie Wonder's music was banned in 1985, after he dedicated his Oscar award to Mandela. Two independent radio stations, Capital Radio and Radio 702 came into being in 1979 and 1980, respectively. Since these were based in the "independent" homelands of Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ba ...

and Bophutatswana, respectively, they were nominally not bound by the government's regulations. Although they tended to follow the decisions of the Directorate, they also played music by bands such as Juluka, which were not featured by the SABC. Neither station, however, played "Sun City" when it was released in 1985, as the owners of the Sun City resort had partial ownership of both stations.

A large number of musicians, including Masekela and Makeba, as well as Abdullah Ibrahim

Abdullah Ibrahim (born Adolph Johannes Brand on 9 October 1934 and formerly known as Dollar Brand) is a South African pianist and composer. His music reflects many of the musical influences of his childhood in the multicultural port areas of Cap ...

were driven into exile by the apartheid government. Songs written by these people were prohibited from being broadcast, as were all songs that opposed the apartheid government. Most of the anti-apartheid songs of the period were censored by the apartheid government. "Bring Him Back Home" was banned in South Africa by the government upon its release. Nonetheless, it became a part of the number of musical voices protesting the apartheid regime, and became an important song for the anti-apartheid movement in the late 1980s. It was declared to be "clean" by the South African government following Mandela's release from prison in 1990.

Artists within South Africa sometimes used subtle lyrics to avoid the censors. The song "Weeping for His Band Bright Blue" by Dan Heymann, a "reluctant army conscript", used "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika", an anthem of the ANC that had been banned, as the backdrop for symbolic lyrics about a man living in fear of an oppressive society. The censor failed to notice this, and the song became immensely popular, reaching No 1 on the government's own radio station. Similarly, jazz musicians would often incorporate melodies of freedom songs into their improvisations. Yvonne Chaka Chaka used the phrase "Winning my dear love" in place of "Winnie Mandela

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela (born Nomzamo Winifred Zanyiwe Madikizela; 26 September 1936 – 2 April 2018), also known as Winnie Mandela, was a South African anti-apartheid activist and politician, and the second wife of Nelson Mandela. She ser ...

", while a compilation album released by Shifty Records

Founded by Lloyd Ross and Ivan Kadey, Shifty Records was a South African anti-apartheid record label which existed for over a decade beginning in 1982. In 1986 Kadey left South Africa and became partner with the Waterland Design Group in Hollyw ...

was titled "A Naartjie in Our Sosatie", which literally meant "a tangerine in our kebab", but represented the phrase "Anarchy in our Society", a play on words that was not picked up by the censors. Keith Berelowitz would later state that he had submitted fake lyrics, replacing controversial terms with innocuous, similar sounding ones. Some artists, however, avoided explicitly political music altogether: scholar Michael Drewett has written that even when musicians avoided political messages, achieving financial success "despite lack of education, poverty, urban squalor, and other difficulties was certainly a triumph" and that such success was part of the struggle to live normally under apartheid.

Other bands used more direct lyrics, and faced censorship and harassment as a result. Savuka

Savuka, occasionally referred to as Johnny Clegg & Savuka, was a multi-racial South African band formed in 1986 by Johnny Clegg after the disbanding of Juluka. Savuka's music blended traditional Zulu musical influences with Celtic music and r ...

, a multi-racial band, were often arrested or had their concerts raided for playing their song "Asimbonanga", which was dedicated to Biko, Mandela, and others associated with the anti-apartheid movement. A musical tour by Voëlvry musicians faced significant opposition from the government. Major surveillance and threats from police sparked trouble at the beginning of the tour, which created issues over suitable venues, and the musicians were forced to play in abandoned buildings. After Roger Lucey wrote a song critical of the secret police, he received threatening visits by them late at night, and had tear gas

Tear gas, also known as a lachrymator agent or lachrymator (), sometimes colloquially known as "mace" after the early commercial aerosol, is a chemical weapon that stimulates the nerves of the lacrimal gland in the eye to produce tears. In ...

poured into an air-conditioning unit during one of his concerts. Lucey's producers were intimidated by the security forces, and his musical recordings confiscated: Lucey himself abandoned his musical career. The song was banned, and an individual could be jailed for five years for owning a copy of it. Musician and public speaker Mzwakhe Mbuli

Mzwakhe Mbuli (born 1 August 1959) is a South African poet, Mbaqanga singer and former Deacon at Apostolic Faith Mission Church in Naledi Soweto, South Africa. Known as "The People's Poet, Tall Man, Mbulism, The Voice Of Reason", he is the father o ...

faced more violent reactions: he was shot at, and a grenade was thrown at his house. After the release of his first album "Change is Pain" in 1986, he was arrested and tortured: the album was banned. The concerts of Juluka were sometimes broken up by the police, and musicians were often arrested under the "pass laws" of the apartheid government. When they were stopped, black musicians were often asked to play for the police, to prove that they were in fact musicians.

Analysis