Murder of Julia Martha Thomas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The murder of Julia Martha Thomas, dubbed the "Barnes Mystery" or the "Richmond Murder" by the press, was one of the most notorious crimes in the

The murder of Julia Martha Thomas, dubbed the "Barnes Mystery" or the "Richmond Murder" by the press, was one of the most notorious crimes in the

Julia Martha Thomas was a former schoolteacher who had been

Julia Martha Thomas was a former schoolteacher who had been

Webster persuaded Thomas to keep her on for a further three days until Sunday 2March. She had Sunday afternoons off as a half-day and was expected to return in time to help Thomas prepare for evening service at the local

Webster persuaded Thomas to keep her on for a further three days until Sunday 2March. She had Sunday afternoons off as a half-day and was expected to return in time to help Thomas prepare for evening service at the local  It was later alleged that Webster had offered two pots of lard to a neighbour, supposed to have been rendered from Thomas's boiled fat. However, no evidence about this was offered at the subsequent trial and it seems likely that the story is merely a legend, particularly as several versions of the story appear to exist. The proprietress of a nearby pub claimed that Webster had visited her establishment and tried to sell what she called "best

It was later alleged that Webster had offered two pots of lard to a neighbour, supposed to have been rendered from Thomas's boiled fat. However, no evidence about this was offered at the subsequent trial and it seems likely that the story is merely a legend, particularly as several versions of the story appear to exist. The proprietress of a nearby pub claimed that Webster had visited her establishment and tried to sell what she called "best

Thomas's murder caused a sensation on both sides of the

Thomas's murder caused a sensation on both sides of the

The murder had a considerable social impact on Victorian Britain and Ireland. It caused an immediate sensation and was widely reported in the press. ''Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser'' of Dublin noted that what it called "one of the most sensational and awful chapters in the annals of human wickedness" had resulted in the press "teem ngwith descriptions and details of the ghastly horrors of that crime".

Such was Webster's notoriety that within only a few weeks of her arrest, and well before she had gone to trial, Madame Tussaud's created a wax effigy of her and put it on display for those who wished to see the "Richmond Murderess". It remained on display well into the twentieth century alongside other notorious killers such as

The murder had a considerable social impact on Victorian Britain and Ireland. It caused an immediate sensation and was widely reported in the press. ''Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser'' of Dublin noted that what it called "one of the most sensational and awful chapters in the annals of human wickedness" had resulted in the press "teem ngwith descriptions and details of the ghastly horrors of that crime".

Such was Webster's notoriety that within only a few weeks of her arrest, and well before she had gone to trial, Madame Tussaud's created a wax effigy of her and put it on display for those who wished to see the "Richmond Murderess". It remained on display well into the twentieth century alongside other notorious killers such as  Exacerbating the crime in the minds of many Victorians was how Webster violated the expected norms of

Exacerbating the crime in the minds of many Victorians was how Webster violated the expected norms of

In 1952, the naturalist

In 1952, the naturalist

The Barnes Mystery

*

The Murderess and the Hangman

'a

Transcript of Kate Webster's trial at the Old Bailey

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, Julia Martha Murder of Julia Martha Thomas Deaths by person in London Deaths from asphyxiation Dismemberments Female murder victims Murder in London History of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Richmond, London March 1879 events 1879 murders in the United Kingdom 1870s murders in London Burials at Barnes Cemetery

The murder of Julia Martha Thomas, dubbed the "Barnes Mystery" or the "Richmond Murder" by the press, was one of the most notorious crimes in the

The murder of Julia Martha Thomas, dubbed the "Barnes Mystery" or the "Richmond Murder" by the press, was one of the most notorious crimes in the Victorian period

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardian ...

of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Thomas, a widow in her 50s who lived in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, was murdered on 2March 1879 by her maid Kate Webster, a 30-year-old Irishwoman with a history of theft. Webster disposed of the body by dismembering it, boiling the flesh off the bones, and throwing most of the remains into the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

.

It was alleged, although never proven, that Webster had offered the fat to a publican

In antiquity, publicans ( Greek τελώνης ''telōnēs'' (singular); Latin ''publicanus'' (singular); ''publicani'' (plural)) were public contractors, in whose official capacity they often supplied the Roman legions and military, managed th ...

, neighbours and street children as dripping

Dripping, also known usually as beef dripping or, more rarely, as pork dripping, is an animal fat produced from the fatty or otherwise unusable parts of cow or pig carcasses. It is similar to lard, tallow and schmaltz.

History

It is used for ...

and lard. Part of Thomas's remains were subsequently recovered from the river. Her severed head remained missing until October 2010, when the skull was found during building works being carried out for Sir David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histor ...

.

After the murder, Webster posed as Thomas for two weeks but was exposed and fled back to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

at her uncle's home at Killanne near Enniscorthy

Enniscorthy () is the second-largest town in County Wexford, Ireland. At the 2016 census, the population of the town and environs was 11,381. The town is located on the picturesque River Slaney and in close proximity to the Blackstairs Mountain ...

, County Wexford. She was arrested there on 29 March and was returned to London, where she stood trial at the Old Bailey in July 1879. At the end of a six-day trial, Webster was convicted and sentenced to death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

after a jury of matrons rejected her last-minute attempt to avoid the death penalty by pleading pregnancy. She finally confessed to the murder the night before she was hanged, on 29 July at Wandsworth Prison

HM Prison Wandsworth is a Prison security categories in the United Kingdom, Category B men's prison at Wandsworth in the London Borough of Wandsworth, South West (London sub region), South West London, England. It is operated by His Majesty's Pri ...

. The case attracted huge public interest and was widely covered by the press in both Britain and Ireland. Webster's behaviour after the crime and during the trial further increased the notoriety of the murder.

Background

Julia Martha Thomas was a former schoolteacher who had been

Julia Martha Thomas was a former schoolteacher who had been widow

A widow (female) or widower (male) is a person whose spouse has died.

Terminology

The state of having lost one's spouse to death is termed ''widowhood''. An archaic term for a widow is "relict," literally "someone left over". This word can so ...

ed twice. Since the death of her second husband in 1873, she had lived on her own at 2Mayfield Cottages (also known as 2Vine Cottages) in Park Road in Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

. The house was a two-storey semi-detached

A semi-detached house (often abbreviated to semi) is a single family duplex dwelling house that shares one common wall with the next house. The name distinguishes this style of house from detached houses, with no shared walls, and terraced hou ...

villa built in grey stone with a garden at the front and back. The area was not heavily populated at the time, although her house was close to a public house

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and wa ...

called The Hole in the Wall.

Thomas was described by her doctor George Henry Rudd as "a small, well-dressed lady" who was about 54 years old. Elliot O'Donnell, summing up contemporary accounts in his introduction to a transcript of Webster's trial, said that Thomas had an "excitable temperament" and was regarded by her neighbours as eccentric. She frequently travelled, leaving her friends and relatives unaware of her whereabouts for weeks or months at a time. Thomas was a member of the lower middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

and as such was not wealthy, but she habitually dressed up and wore jewellery to give the impression of prosperity. Her desire to employ a live-in domestic servant

A domestic worker or domestic servant is a person who works within the scope of a residence. The term "domestic service" applies to the equivalent occupational category. In traditional English contexts, such a person was said to be "in service ...

probably had as much to do with status as with practicality. However, she had a reputation for being a harsh employer and her irregular habits meant that she had difficulty finding and retaining servants. Before 1879, Thomas had been able to keep only one maid for any length of time.

On 29 January 1879, Thomas took on Kate Webster as her servant. Webster had been born as Kate Lawler in Killanne, County Wexford, near Enniscorthy

Enniscorthy () is the second-largest town in County Wexford, Ireland. At the 2016 census, the population of the town and environs was 11,381. The town is located on the picturesque River Slaney and in close proximity to the Blackstairs Mountain ...

, in about 1849. She was later described by ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' as "a tall, strongly-made woman of about in height with sallow and much freckled complexion and large and prominent teeth". The details of Webster's early life are unclear, as many of her later autobiographical statements proved unreliable, but she claimed to have been married to a sea captain called Webster by whom she had four children.

According to Webster's account, all the children died, as did her husband, within a short time of each other. She was imprisoned for larceny

Larceny is a crime involving the unlawful taking or theft of the personal property of another person or business. It was an offence under the common law of England and became an offence in jurisdictions which incorporated the common law of Eng ...

in Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 ...

in December 1864, when she was only about 15 years old, and came to England in 1867. In February 1868, she was sentenced to four years of penal servitude for committing larceny in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

.

Webster was released from jail in January 1872 and, by 1873, she had moved to Rose Gardens in Hammersmith, West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North Londo ...

, where she became friends with a neighbouring family named Porter. On 18 April 1874, she gave birth to a son whom she named John W. Webster in Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable ...

. The identity of the father is unclear, as she named three different men at various times. One, a man named Strong, was her accomplice in further robberies

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take anything of value by force, threat of force, or by use of fear. According to common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the perso ...

and thefts. She later claimed to have been forced into crime, as she had been "forsaken by him, and committed crimes for the purpose of supporting myself and child".

Webster moved frequently around West London using various aliases

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

, including Webb, Webster, Gibbs, Gibbons, and Lawler. While living in Teddington

Teddington is a suburb in south-west London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. In 2021, Teddington was named as the best place to live in London by ''The Sunday Times''. Historically in Middlesex, Teddington is situated on a long me ...

, she was arrested and convicted in May 1875 of 36 charges of larceny. She was sentenced to eighteen months in Wandsworth Prison

HM Prison Wandsworth is a Prison security categories in the United Kingdom, Category B men's prison at Wandsworth in the London Borough of Wandsworth, South West (London sub region), South West London, England. It is operated by His Majesty's Pri ...

. Not long after leaving prison, Webster was arrested again for larceny and was sentenced to another twelve months' imprisonment in February 1877. Her young son was cared for in her absence by Sarah Crease, a friend who worked as a charwoman

A charwoman (also chargirl, charlady or char) is an old-fashioned occupational term, referring to a paid part-time worker who comes into a house or other building to clean it for a few hours of a day or week, as opposed to a maid, who usually ...

for a Miss Loder in Richmond.

In January 1879, Crease fell ill and Webster stood in for her as a temporary replacement at Loder's house. Loder knew Thomas as a friend and was aware of her wish to find a domestic servant. She recommended Webster on the basis of the latter's temporary work for her. When Thomas met Webster, she engaged her on the spot, though she did not appear to have made any inquiries about Webster's character or past. After Webster was taken on by Thomas, the relationship between the two women appears to have deteriorated rapidly. Thomas disliked the quality of Webster's work and frequently criticised it. Webster later said:

Webster in turn became increasingly resentful of Thomas, to the point that Thomas attempted to persuade friends to stay with her as she did not like to be alone with Webster. It was arranged that Webster would leave Thomas's service on 28 February. Thomas recorded her decision in her last diary entry: "Gave Katherine warning to leave".

Murder and the disposal of the body

Webster persuaded Thomas to keep her on for a further three days until Sunday 2March. She had Sunday afternoons off as a half-day and was expected to return in time to help Thomas prepare for evening service at the local

Webster persuaded Thomas to keep her on for a further three days until Sunday 2March. She had Sunday afternoons off as a half-day and was expected to return in time to help Thomas prepare for evening service at the local Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

church. On this occasion, however, Webster visited the local alehouse and returned late, delaying Thomas's departure. The two women quarrelled and several members of the congregation later reported that Thomas had appeared "very agitated" on arriving at the church. She told a fellow congregant that she had been delayed by "the neglect of her servant to return home at the proper time", and said that Webster had "flown into a terrible passion" upon being rebuked. Thomas returned home from church early, about 9pm, and confronted Webster. According to Webster's eventual confession:

The neighbours, a woman named Ives (Thomas's landlady) and her mother, heard a single thump like that of a chair falling over but paid no heed to it at the time. Next door, Webster began disposing of the body by dismembering it and boiling it in the laundry copper and burning the bones in the hearth. She later described her actions:

The neighbours noticed an unusual, unpleasant smell. Webster spoke later of how she was "greatly overcome, both from the horrible sight before me and the smell". However, the activity at 2Mayfield Cottages did not seem to be out of the ordinary, as it was customary in many households for the washing to begin early on Monday morning. Over the next couple of days, Webster continued cleaning the house and Thomas's clothes and to put on a show of normality for people who called for orders. Behind the scenes, she was packing the dismembered remains into a black Gladstone bag and a corded wooden bonnet-box. She was unable to fit the murdered woman's head and one of the feet into the containers and disposed of them separately, throwing the foot onto a rubbish heap in Twickenham

Twickenham is a suburban district in London, England. It is situated on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historically part of Middlesex, it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames since 1965, and the boroug ...

. The head was buried under the Hole in the Wall's stables a short distance from Thomas's house, where it was found 131 years later.

On 4 March, Webster travelled to Hammersmith to see her old neighbours the Porters, whom she had not seen for six years, wearing Thomas's silk dress and carrying the Gladstone bag which she had filled with some of the remains. Webster introduced herself to the Porters as "Mrs. Thomas". She claimed that, since last meeting the Porters, she had married, had a child, been widowed, and had been left a house in Richmond by an aunt. She invited Porter and his son Robert to a pub, the Oxford and Cambridge Arms, in Barnes

Barnes may refer to:

People

* Barnes (name), a family name and a given name (includes lists of people with that name)

Places

United Kingdom

*Barnes, London, England

**Barnes railway station

** Barnes Bridge railway station

** Barnes Railway Bri ...

. Along the way, she disposed of the bag that she was carrying, probably by dropping it into the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

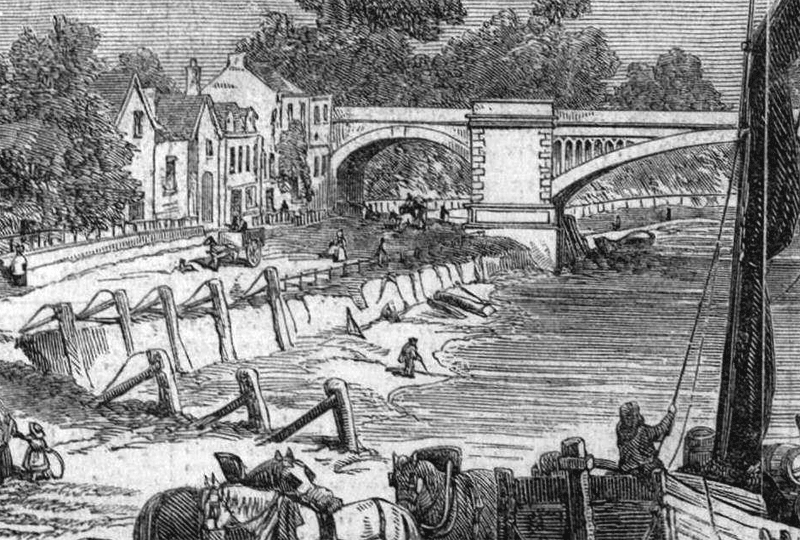

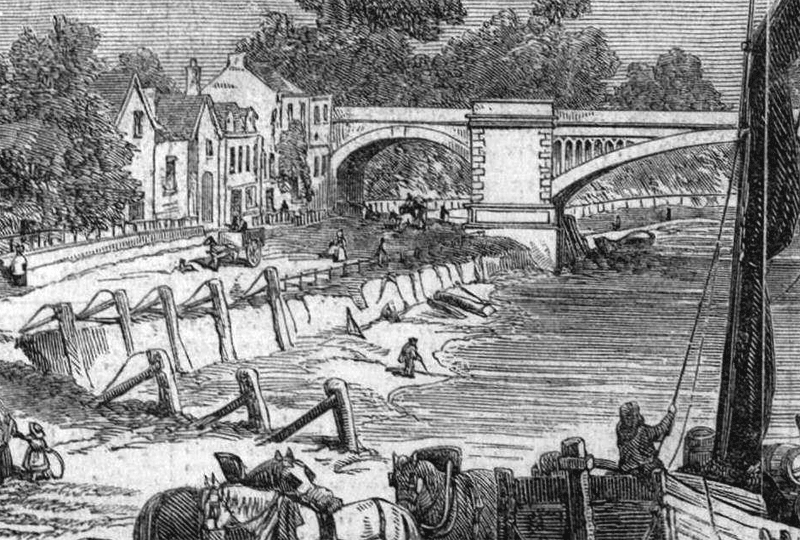

, while the Porters were inside the pub drinking. It was never recovered. Webster then asked young Robert Porter if he could help her carry a heavy box from 2Mayfield Cottages to the station. As they crossed Richmond Bridge, Webster dropped the box into the Thames. She was able to explain it away and did not arouse Robert's suspicions.

The following day, however, the box was found washed up in shallow water next to the river bank about five miles downstream. It was spotted by Henry Wheatley, a coal porter who was driving his cart past Barnes Railway Bridge

Barnes Railway Bridge is a Grade II listed railway bridge in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames and the London Borough of Hounslow. It crosses the River Thames in London in a northwest to southeast direction at Barnes. It carries the ...

shortly before seven in the morning. He initially thought that the box might contain the proceeds of a burglary. He recovered the box and opened it, finding that it contained what looked like body parts wrapped in brown paper. The discovery was immediately reported to the police and the remains were examined by a doctor, who found that they consisted of the trunk (minus entrails) and legs (minus one foot) of a woman. The head was missing and was later assumed to have been thrown into the river separately by Webster.

Around the same time, a human foot and ankle were found in Twickenham. It was clear that all of the remains belonged to the same corpse, but there was nothing to connect them with Thomas and no means to identify the remains. The doctor who examined the body parts erroneously attributed them to "a young person with very dark hair". An inquest on 10–11 March resulted in an open verdict The open verdict is an option open to a coroner's jury at an inquest in the legal system of England and Wales. The verdict means the jury confirms the death is suspicious, but is unable to reach any other verdicts open to them. Mortality studies c ...

on the cause of death, and the unidentified remains were laid to rest in Barnes Cemetery

Barnes Cemetery, also known as Barnes Old Cemetery, is a disused cemetery in Barnes, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It is located off Rocks Lane on Barnes Common.

History

The cemetery was established in 1854 on two acres of san ...

on 19 March. The newspapers dubbed the unexplained murder the "Barnes Mystery", amid speculation that the body had been used for dissection and anatomical study.

It was later alleged that Webster had offered two pots of lard to a neighbour, supposed to have been rendered from Thomas's boiled fat. However, no evidence about this was offered at the subsequent trial and it seems likely that the story is merely a legend, particularly as several versions of the story appear to exist. The proprietress of a nearby pub claimed that Webster had visited her establishment and tried to sell what she called "best

It was later alleged that Webster had offered two pots of lard to a neighbour, supposed to have been rendered from Thomas's boiled fat. However, no evidence about this was offered at the subsequent trial and it seems likely that the story is merely a legend, particularly as several versions of the story appear to exist. The proprietress of a nearby pub claimed that Webster had visited her establishment and tried to sell what she called "best dripping

Dripping, also known usually as beef dripping or, more rarely, as pork dripping, is an animal fat produced from the fatty or otherwise unusable parts of cow or pig carcasses. It is similar to lard, tallow and schmaltz.

History

It is used for ...

" there. Leonard Reginald Gribble, a writer on criminology, commented that "there is no acceptable evidence that such a repulsive sale was ever made, and it is more than possible that the episode belongs rightfully with the rest of the vast collection of apocryphal stories that has accumulated, not unnaturally, about the persons and deeds of famous criminals."

Webster continued to live at 2Mayfield Cottages while posing as Thomas, wearing her late employer's clothes and dealing with tradesmen under her newly assumed identity. On 9March, she reached an agreement with John Church, a victualler

A victualler is traditionally a person who supplies food, beverages and other provisions for the crew of a vessel at sea.

There are a number of other more particular uses of the term, such as:

* The official supplier of food to the Royal Navy in ...

from Hammersmith, to sell Thomas's furniture and other goods to furnish his pub, the Rising Sun. He agreed to pay her £68 with an interim payment of £18 in advance.

By the time that the removal horse and cart arrived on 18 March, the neighbours were becoming increasingly suspicious, as they had not seen Thomas for nearly two weeks. Her next door neighbour and landlady Miss Ives asked the deliverymen who had ordered the goods removed. They replied "Mrs Thomas" and indicated Webster. Realising that she had been exposed, Webster fled immediately, catching a train to Liverpool and travelling from there to her family home at Enniscorthy.

Meanwhile, Church realised that he had been deceived. When he went through the clothes in the delivery van, he found a letter addressed to the real Thomas. The police were called in and searched 2Mayfield Cottages. There they discovered blood stains, burned finger-bones in the hearth and fatty deposits behind the copper, as well as a letter left by Webster giving her home address in Ireland. They immediately put out a "wanted" notice giving a description of Webster and her son. Detectives from Scotland Yard soon discovered that Webster and her son had fled back to Ireland aboard a coal steamer.

The head constable of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

(RIC) in Wexford realised that the woman being sought by Scotland Yard was the same person whom his force had arrested fourteen years previously for larceny. The RIC were able to trace Webster to her uncle's farm at Killanne near Enniscorthy and arrested her there on 29 March. She was taken to Kingstown (modern Dún Laoghaire

Dún Laoghaire ( , ) is a suburban coastal town in Dublin in Ireland. It is the administrative centre of Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown.

The town was built following the 1816 legislation that allowed the building of a major port to serve Dubli ...

) and from there back to Richmond via Holyhead, in the custody of the Scotland Yard policemen.

On hearing of the crime with which she was charged, Webster's uncle refused to give shelter to her son, and the authorities sent the boy to the local workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

until such time as a place could be found for him in an industrial school.

Webster's trial and execution

Thomas's murder caused a sensation on both sides of the

Thomas's murder caused a sensation on both sides of the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

. When the news broke, many people travelled to Richmond to look at Mayfield Cottages. The crime was just as notorious in Ireland; as Webster travelled under arrest from Enniscorthy to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

, crowds gathered to gawk and jeer at her at nearly every station between the two locations. The pre-trial magistrates' hearings were attended by "many privileged and curious persons... including not a few ladies", according to the '' Manchester Guardian''. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' reported that Webster's first appearance at Richmond Magistrates' Court was greeted by "an immense crowd yesterday around the building... and very great excitement prevailed."

Webster went on trial at the Central Criminal Courtthe Old Baileyon 2July 1879. In a sign of the great public interest aroused by the case, the prosecution

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

was led by the Solicitor General, Sir Hardinge Giffard. Webster was defended by a prominent London barrister, Warner Sleigh, and the case was presided over by Mr. Justice Denman. The trial was just as well-attended as the earlier hearings in Richmond and attracted intense interest from all levels of society; on the fourth day of the trial, the Crown Prince of Swedenthe future King GustafVturned up to watch the proceedings.

Over the course of six days, the court heard a succession of witnesses piecing together the complicated story of how Thomas had met her death. Webster had attempted before the trial to implicate the publican

In antiquity, publicans ( Greek τελώνης ''telōnēs'' (singular); Latin ''publicanus'' (singular); ''publicani'' (plural)) were public contractors, in whose official capacity they often supplied the Roman legions and military, managed th ...

John Church and her former neighbour Porter, but both men had solid alibi

An alibi (from the Latin, '' alibī'', meaning "somewhere else") is a statement by a person, who is a possible perpetrator of a crime, of where they were at the time a particular offence was committed, which is somewhere other than where the crim ...

s and were cleared of any involvement in the murder. She pleaded not guilty and her defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

sought to emphasise the circumstantial nature of the evidence, highlighting her devotion to her son as a reason why she could not have been capable of the murder. However, Webster's public unpopularity, impassive demeanour and scanty defence counted strongly against her.

A particularly damning piece of evidence came from a bonnetmaker named Maria Durden who told the court that Webster had visited her a week before the murder and had said that she was going to Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

to sell some property, jewellery and a house that her aunt had left her. The jury interpreted this as a sign that Webster had premeditated the murder and convicted her after deliberating for about an hour and a quarter.

Shortly after the jury returned its verdict and just before the judge was about to pass sentence, Webster was asked if there was any reason why sentence of death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

should not be passed upon her. She pleaded that she was pregnant in an apparent bid to avoid the death penalty. ''The Law Times'' reported that " on this a scene of uncertainty, if not of confusion, ensued, certainly not altogether in harmony with the solemnity of the occasion." The judge commented that "after thirty-two years in the profession, he was never at an inquiry of this sort."

Eventually the Clerk of Assize suggested using the archaic mechanism of a jury of matrons, constituted from a selection of the women attending the court, to rule upon the question of whether Webster was "with quick child". Twelve women were sworn in along with a surgeon named Bond, and they accompanied Webster to a private room for an examination that only took a couple of minutes. They returned a verdict that Webster was not "quick with child", though this did not necessarily mean that she was not pregnanta distinction that led the president of the Obstetrical Society of London to protest at the use of "the obsolete medical assumption that the unborn child is not alive until the so-called 'quickening

In pregnancy terms, quickening is the moment in pregnancy when the pregnant woman starts to feel the fetus' movement in the uterus.

Medical facts

The first natural sensation of quickening may feel like a light tapping or fluttering. These sensat ...

'".

A few days before Webster was due to be executed an appeal was submitted on her behalf to the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, R. A. Cross. It was turned down with an official statement that after considering the arguments put forward, the Home Secretary had "failed to discover any sufficient ground to justify him in advising Her Majesty to interfere with the due course of the law".

Before she was executed, Webster made two statements confessing to the crime. In her first, she implicated Strong, the purported father of her child, who she said had participated in the murder and was responsible for leading her into a life of crime. She recanted on 28 July, the night before she was due to be executed, making a further statement in which she took sole responsibility and exonerated Church, Porter and Strong of any involvement. She was hanged the following day at Wandsworth Prison at 9am, where the hangman, William Marwood

William Marwood (1818 – 4 September 1883) was a hangman for the British government. He developed the technique of hanging known as the " long drop".

Early life

Marwood was born in 1818 in the village of Goulceby, the fifth of ten childre ...

, used his newly developed long drop technique to cause instantaneous death. After her death was certified, she was buried in an unmarked grave in one of the prison's exercise yards. The crowd waiting outside cheered as a black flag was raised over the prison walls, signifying that the death sentence had been carried out.

An auction of Thomas's property was held at 2Mayfield Cottages on the day after Webster's execution. Church managed to obtain Thomas's furniture after all, along with numerous other personal effects including her pocket-watch and the knife with which she had been dismembered. The copper in which the body had been boiled was sold for five shillings. Other visitors contented themselves with taking small pebbles and twigs from the garden as souvenirs. The house itself remained unoccupied until 1897, as nobody would live there after the murder. Even then, according to the occupant, servants were reluctant to work at such a notorious place.

It was later rumoured that a "ghostly nun" could be seen hovering over the place where Thomas had been buried. To the surprise and disappointment of Elliott O'Donnell, there was no sign that her house was haunted, and Guy Logan noted that the "neat and pretty" appearance of the property gave no hint of the crime that had been committed within: "anything less like the popular conception of a 'murder house' it would be hard to imagine."

Social impact of the murder

The murder had a considerable social impact on Victorian Britain and Ireland. It caused an immediate sensation and was widely reported in the press. ''Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser'' of Dublin noted that what it called "one of the most sensational and awful chapters in the annals of human wickedness" had resulted in the press "teem ngwith descriptions and details of the ghastly horrors of that crime".

Such was Webster's notoriety that within only a few weeks of her arrest, and well before she had gone to trial, Madame Tussaud's created a wax effigy of her and put it on display for those who wished to see the "Richmond Murderess". It remained on display well into the twentieth century alongside other notorious killers such as

The murder had a considerable social impact on Victorian Britain and Ireland. It caused an immediate sensation and was widely reported in the press. ''Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser'' of Dublin noted that what it called "one of the most sensational and awful chapters in the annals of human wickedness" had resulted in the press "teem ngwith descriptions and details of the ghastly horrors of that crime".

Such was Webster's notoriety that within only a few weeks of her arrest, and well before she had gone to trial, Madame Tussaud's created a wax effigy of her and put it on display for those who wished to see the "Richmond Murderess". It remained on display well into the twentieth century alongside other notorious killers such as Burke and Hare

The Burke and Hare murders were a series of sixteen killings committed over a period of about ten months in 1828 in Edinburgh, Scotland. They were undertaken by William Burke and William Hare, who sold the corpses to Robert Knox for dissection ...

and Hawley Harvey Crippen

Hawley Harvey Crippen (September 11, 1862 – November 23, 1910), usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopath, ear and eye specialist and medicine dispenser. He was hanged in Pentonville Prison in London for the murder of his wife Co ...

.

Within days of Webster's execution an enterprising publisher on the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

rushed into print a souvenir booklet for the price of a penny, "The Life, Trial and Execution of Kate Webster", which was advertised as "compris ngTwenty Handsome Pages, containing her entire History, with Summing-up, Verdict, and interesting particulars, together with her last words, and a FULL-PAGE ENGRAVING of the EXECUTIONPortraits, Illustrations &c." '' The Illustrated Police News'' published a souvenir cover depicting an artist's impression of the day of the execution. It depicted "the prisoner visited by her friends", "the process of pinioning", the final rites being said, "hoisting the black flag", and finally "filling up the coffin with lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

".

The case was also commemorated, while it was still ongoing, by street ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads derive from the medieval French ''chanson balladée'' or ''ballade'', which were originally "dance songs". Ballads were particularly characteristic of the popular poetry and ...

smusical narratives set to the tune of popular songs. H. Such, a printer and publisher in Southwark, issued a ballad entitled "Murder and Mutilation of an Old Lady near Barnes" shortly after Webster had been arrested, set to the tune of " Just Before the Battle, Mother", a popular song of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. At the end of the trial Such issued another ballad, set to the tune of "Driven from Home", announcing:

Webster herself was characterised as malicious, reckless and wilfully evil. Commentators saw her crime as both gruesome and scandalous. Servants were expected to be deferential; her act of extreme violence towards her employer was deeply disquieting. At the time, about 40% of the female labour force was employed as domestic servants for a very wide range of society, from the wealthiest to respectable working-class families. Servants and employers lived and worked in close proximity, and the honesty and orderliness of servants was a constant cause of concern. Servants were very poorly paid and larceny was an ever-present temptation. Had Webster succeeded in completing the deal with Church to sell Thomas's furniture, she stood to gain the equivalent of two to three years' worth of wages. Another cause of revulsion against Webster was her attempt to impersonate Thomas. She had managed to perpetrate the impersonation for two weeks, implying that middle-class identity amounted to little more than cultivating the right demeanour and having the appropriate clothes and possessions, whether or not they had been earned. Church, whom Webster had attempted to implicate, was himself a former servant who had risen to lower middle-class status and earned a measure of prosperity and effective management of his pub. His commitment to bettering himself through hard work was in keeping with the ethic of the time. Webster, in contrast, had simply stolen her briefly-held middle-class identity.The terrible crime at Richmond at last, On Catherine Webster now has been cast, Tried and found guilty she is sentenced to die. From the strong hand of justice she cannot fly. She has tried all excuses but of no avail, About this and murder she's told many tales, She has tried to throw blame on others as well, But with all her cunning at last she has fell.

Exacerbating the crime in the minds of many Victorians was how Webster violated the expected norms of

Exacerbating the crime in the minds of many Victorians was how Webster violated the expected norms of femininity

Femininity (also called womanliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles generally associated with women and girls. Femininity can be understood as socially constructed, and there is also some evidence that some behaviors considered f ...

by the standards of the Victorian era. Victorian ideals saw women as moral, passive and physically weak or restrained. Webster was seen as quite the opposite and was described in lurid ways that emphasised her lack of femininity. Elliott O'Donnell, writing in his introduction to the trial transcript, described Webster as "not merely savage, savage and shocking... but the grimmest of grim personalities, a character so uniquely sinister and barbaric as to be hardly human." The newspapers described her as "gaunt, repellent, and trampish-looking", though the reporter for ''The Penny Illustrated Paper and Illustrated Times

The ''Penny Illustrated Paper'' was a cheap ( 1d.) illustrated London weekly newspaper that ran from 1861 to 1913.

Premises

Illustrated weekly newspapers had been pioneered by the ''Illustrated London News'' (published from 1842, costing fivepe ...

'' commented that she was "not so ill-favoured as she has been described".

Webster's appearance and behaviour were seen as key signs of her inherently criminal nature. Crimes were thought to be committed by a social "residuum" at the bottom of society who occupied themselves as "habitual criminals", choosing to live a life of drink and theft rather than improving themselves through thrift and hard work. Her strong build, partly a result of the hard physical labour that was her livelihood, ran counter to the largely middle-class notion that women were meant to be physically frail. Some commentators saw her facial features as indicative of criminality; O'Donnell commented upon her "obliquely set eyes", which he declared "are not infrequently found in homicides... this peculiarity, which I consider was sufficient in itself, as one of nature's danger signals, to have warned people to steer clear of her."

Webster's behaviour in court and her sexual history also counted against her. She was widely described by reporters as "calm" and "stolid" in facing the court and cried only once during the trial, when her son was mentioned. This contradicted the expectation that "properly feminine" women should be penitent and emotional in such a situation. Her succession of male friends, one of whom had fathered her child outside wedlock, suggested promiscuous

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by ma ...

female sexualityagain, strongly counter to expected norms of behaviour. During her trial Webster attempted unsuccessfully to evoke sympathy by blaming Strong, the possible father of her child, for leading her astray: "I formed an intimate acquaintance with one who should have protected me and was led away by evil associates and bad companions." This claim played on social expectations that women's moral sense was inextricably linked with chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when ma ...

"falling" sexually would lead to other forms of "ruin"and that men who had sexual relations with women acquired social obligations that they were expected to fulfil. Webster's attempt to implicate three innocent men also caused outrage; O'Donnell commented that "public opinion, as a whole, undoubtedly condemned Kate Webster, as much, perhaps, for her attempts to bring three innocent men to the scaffold as for the actual murder itself."

According to Shani D'Cruze of the Feminist Crime Research Network, the fact that Webster was Irish was a significant factor in the widespread revulsion felt towards her in Britain. Many Irish people had emigrated to England since the Great Famine of 1849, but met widespread prejudice and persistent associations with criminality and drunkenness. The Irish were at worst depicted as bestial and subhuman, and there were repeated episodes of violence between Irish and English workers as well as attacks by Fenians (Irish nationalists) in England. The demonisation of Webster as "hardly human", as O'Donnell put it, was of a piece with the public and judicial perceptions of the Irish as innately criminal.

Discovery of Thomas's skull

In 1952, the naturalist

In 1952, the naturalist Sir David Attenborough

Sir David Frederick Attenborough (; born 8 May 1926) is an English broadcaster, biologist, natural historian and author. He is best known for writing and presenting, in conjunction with the BBC Natural History Unit, the nine natural histor ...

and his wife Jane bought a house situated between the former Mayfield Cottages (which still stand today) and the Hole in the Wall pub. The pub closed in 2007 and fell into dereliction but was bought by Attenborough in 2009 to be redeveloped.

On 22 October 2010, workmen carrying out excavation work at the rear of the old pub uncovered a "dark circular object", which turned out to be a woman's skull. It had been buried underneath foundations that had been in place for at least forty years, on the site of the pub's stables. It was immediately speculated that the skull was Thomas's, and the coroner asked Richmond police to carry out an investigation into the identity and circumstances of death of the skull's owner.

Carbon dating carried out at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

dated the skull to between 1650 and 1880, while the fact that it had been deposited on top of a layer of Victorian tiles suggested that it belonged to the end of this era. The skull had fracture marks consistent with Webster's account of throwing Thomas down the stairs, and it was found to have low collagen levels, consistent with it being boiled. In July 2011, the coroner concluded that the skull was indeed that of Thomas. DNA testing was not possible as she had died childless and no relatives could be traced; in addition, there was no record of where exactly in Barnes Cemetery the rest of her body had been buried.

The coroner recorded a verdict of unlawful killing

In English law, unlawful killing is a verdict that can be returned by an inquest in England and Wales when someone has been killed by one or more unknown persons. The verdict means that the killing was done without lawful excuse and in breach of ...

, superseding the open verdict recorded in 1879. The cause of Thomas's death was given as asphyxiation and a head injury. The police called the outcome "a good example of how good old-fashioned detective work, historical records and technological advances came together to solve the 'Barnes Mystery'".

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Barnes Mystery

*

The Murderess and the Hangman

'a

biographical novel

The biographical novel is a genre of novel which provides a fictional account of a contemporary or historical person's life. Like other forms of biographical fiction, details are often trimmed or reimagined to meet the artistic needs of the fict ...

by Matt Fullerty about the murder and Webster's trial.

* September 2011 Discovery Channel documentary about the case

Transcript of Kate Webster's trial at the Old Bailey

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thomas, Julia Martha Murder of Julia Martha Thomas Deaths by person in London Deaths from asphyxiation Dismemberments Female murder victims Murder in London History of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Richmond, London March 1879 events 1879 murders in the United Kingdom 1870s murders in London Burials at Barnes Cemetery