Montgomery C. Meigs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

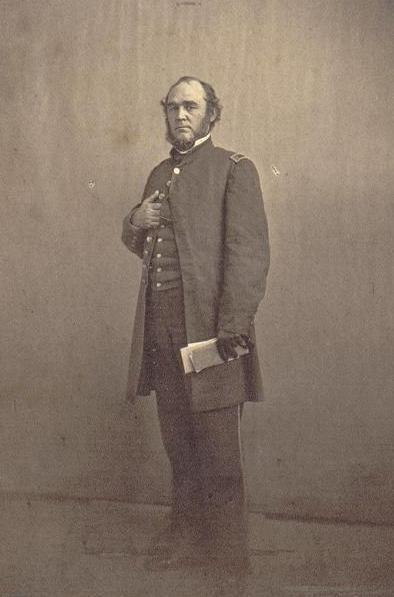

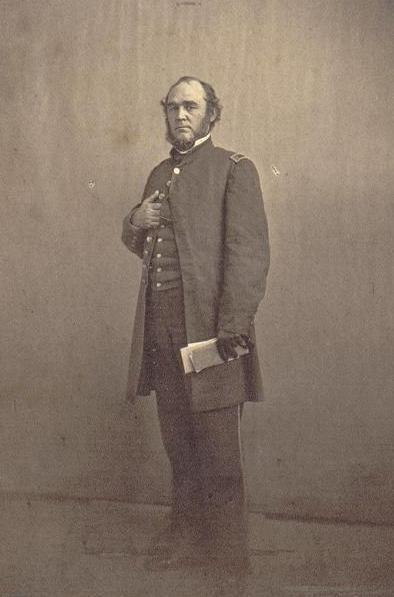

Montgomery Cunningham Meigs (; May 3, 1816 – January 2, 1892) was a career

Accessed 2012-12-15. His grandfather, In the fall of 1860, as a result of a disagreement over procurement contracts, Meigs incurred the ill will of the

In the fall of 1860, as a result of a disagreement over procurement contracts, Meigs incurred the ill will of the

While Meigs served as Quartermaster General throughout the war he went on an extensive inspection tour from August 1863 to January 1864. During that time Colonel Charles Thomas acted in his stead back in Washington, D.C. Meigs' field services during the Civil War included command of

While Meigs served as Quartermaster General throughout the war he went on an extensive inspection tour from August 1863 to January 1864. During that time Colonel Charles Thomas acted in his stead back in Washington, D.C. Meigs' field services during the Civil War included command of

Accessed 2012-05-03. In May 1864, Union forces suffered large numbers of dead in the

Accessed 2012-05-03. Although the first military burial at Arlington had been made on May 13,Cultural Landscape Program, p. 86.

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs did not authorize establishment of burials until June 15, 1864.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 85.

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs ordered that the estate be surveyed and that be set aside for use as a cemetery.

Meigs played a critical role in developing Arlington National Cemetery, both during the Civil War and afterward.

Although most burials initially occurred near the freedmen's cemetery in the estate's northeast corner, in mid-June 1864 Meigs ordered that burials commence immediately on the grounds of

Meigs played a critical role in developing Arlington National Cemetery, both during the Civil War and afterward.

Although most burials initially occurred near the freedmen's cemetery in the estate's northeast corner, in mid-June 1864 Meigs ordered that burials commence immediately on the grounds of

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs hated Lee for betraying the Union, and ordered that more burials occur near the house to make it politically impossible for disinterment to occur. Meigs himself designed and implemented most of the changes at the cemetery in the 15 years after the war. In 1865, for example, Meigs decided to build a monument to Civil War dead in the center of a grove of trees west of the Lee's flower garden.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 96.

Accessed 2012-04-29. U.S. Army troops were dispatched to investigate every battlefield within a radius of the city of Washington, D.C. The bodies of 2,111 Union and Confederate dead were collected, most of them from the battlefields of Meigs made additional major changes to the cemetery in the 1870s. In 1870, he ordered that a "Sylvan Hall"—a series of three cruciform tree plantings, one inside the other—be planted in the "Field of the Dead" (in what is now Section 13). A year later, Meigs ordered the

Meigs made additional major changes to the cemetery in the 1870s. In 1870, he ordered that a "Sylvan Hall"—a series of three cruciform tree plantings, one inside the other—be planted in the "Field of the Dead" (in what is now Section 13). A year later, Meigs ordered the

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs himself designed the amphitheater. Meigs continued to work to ensure that the Lee family could never take control of Arlington. In 1882, the

Accessed 2012-05-03. Since not enough marble was available to rebuild the dome, a tin dome (molded and painted to look like marble) was installed, instead. The Temple of Fame was demolished in 1967.

Meigs became a permanent resident of the District of Columbia after the war. He purchased a home located at 1239 Vermont Avenue NW (at the corner of Vermont Avenue and N Street).

As Quartermaster General after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (constructed between 1866 and 1867), the

Meigs became a permanent resident of the District of Columbia after the war. He purchased a home located at 1239 Vermont Avenue NW (at the corner of Vermont Avenue and N Street).

As Quartermaster General after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (constructed between 1866 and 1867), the

Included in his design was a long sculptured frieze executed by

Included in his design was a long sculptured frieze executed by

Cultural Landscape Program. ''Arlington House: The Robert E. Lee Memorial Cultural Landscape Report.'' National Capital Region. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: 2001.

* Dickinson, William C. and Dean A. Herrin. ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital'' (2002) * East, Sherrod E. "Montgomery C. Meigs and the Quartermaster Department." ''Military Affairs'' (1961): 183–196. in JSTOR*Eicher, John H. and Eicher, David J. ''Civil War High Commands.'' Palo Alto, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2001, . *Farwell, Byron. ''The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare.'' New York: Norton, 2001. *Field, Cynthia R. "A Rich Repast of Classicism: Meigs and Classical Sources." In ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital.'' William C Dickinson, Dean A Herrin, and Donald R Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001. * Freeman, Douglas S.br>''R. E. Lee, A Biography''

4 vol. New York: Scribners, 1934. *Hannan, Caryn, ed. ''Georgia Biographical Dictionary.'' Vol. 1. Hamburg, Mich.: State History Publications, 2008. *Herrin, Dean A. "The Eclectic Engineer: Montgomery C. Meigs and His Engineering Projects." In ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital.'' William C Dickinson, Dean A Herrin, and Donald R Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001. *Holt, Dean W. ''American Military Cemeteries.'' Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2010. *Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs and Ware, Thomas Clayton. ''Theodore O'Hara: Poet-Soldier of the Old South.'' Lexington, Ky.: University of Tennessee Press, 1998. *McDaniel, Joyce L. ''The Collected Works of Caspar Buberl: An Analysis of a Nineteenth Century American Sculptor'' Master's Thesis. Wellesley University, 1976. *Miller, David W. ''Second Only to Grant: Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs.'' Shippensburg, Pa.: White Maine Books, 2000. *Morton, Thomas G. ''The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751-1895.'' Philadelphia: Times Printing House, 1895. *Peters, James Edward. ''Arlington National Cemetery, Shrine to America's Heroes.'' Bethesda, Md.: Woodbine House, 2000. *Poole, Robert M. ''On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery.'' New York: Walker, 2009. * *Schama, Simon. ''The American Future: A History.'' New York: Ecco, 2009. *Scott, Pamela and Lee, Antoinette J. ''Buildings of the District of Columbia'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. *Ulbrich, David. "Montgomery Cunningham Meigs." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History.'' David S. Heidler, and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . *Weigley, Russell F

''Quartermaster General of the Union Army: A Biography of M.C. Meigs.''

New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. *Wilson, Mark R. ''The Business of Civil War: Military Mobilization and the State, 1861-1865.'' Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. *Wolff, Wendy, ed. ''Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journals of Montgomery C. Meigs.'' Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001.

National Academy of Sciences Biographical MemoirMeigs Family papers

at

Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, U.S.A. historical marker – Georgia Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Meigs, Montgomery C. 1816 births 1892 deaths 19th-century American architects Architects of the Capitol Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Logistics personnel of the United States military Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War People from Augusta, Georgia Quartermasters General of the United States Army Southern Unionists in the American Civil War Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

officer and civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

, who served as Quartermaster General of the U.S. Army during and after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. Meigs strongly opposed secession and supported the Union; his record as Quartermaster General was regarded as outstanding, both in effectiveness and in ethical probity, and Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

viewed it as a key factor in the Union victory.

Meigs was one of the principal architects of Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

; the choice of its location, on Robert E. Lee's family estate, Arlington House Arlington House may refer to:

*Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial

*Arlington House (London) a hostel for the homeless in London, England, and one of the Rowton Houses

*Arlington House, Margate, an eighteen-storey residential apartment bloc ...

, was partly a gesture to humiliate Lee for siding with the Confederacy.

Early life and engineering projects

Meigs was born inAugusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

, in May 1816. He was the son of Dr. Charles Delucena Meigs

Charles Delucena Meigs (February 19, 1792 – June 22, 1869) was an American obstetrician of the nineteenth century who is remembered for his opposition to obstetrical anesthesia and to advocating the idea that physicians' hands could not transmi ...

and Mary Montgomery Meigs.Hannan, p. 140. His father was a nationally known obstetrician

Obstetrics is the field of study concentrated on pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. As a medical specialty, obstetrics is combined with gynecology under the discipline known as obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), which is a surgi ...

and professor of obstetrics at Jefferson Medical College

Thomas Jefferson University is a private research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Established in its earliest form in 1824, the university officially combined with Philadelphia University in 2017. To signify its heritage, the univer ...

.Ferguson, p. 52."General Montgomery Cunningham Meigs." ''Scientific American.'' January 30, 1892, p. 71.Accessed 2012-12-15. His grandfather,

Josiah Meigs

Josiah Meigs (August 21, 1757 – September 4, 1822) was an American academic, journalist and government official. He was the first acting president of the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, where he implemented the university's first physic ...

, graduated from Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

(where he was a classmate of future dictionary creator Noah Webster

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5– ...

and American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

general and politician Oliver Wolcott

Oliver Wolcott Sr. (November 20, 1726 December 1, 1797) was an American Founding Father and politician. He was a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation as a representative of Connecticut, and t ...

), and later was president of the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

. Montgomery Meigs' mother, Mary, was the granddaughter of a Scottish family from Brigend (with somewhat distant claims to a baronetcy

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

) which emigrated to America in 1701.

Meigs' father apprenticed as a physician in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

until 1812, at which time he moved to Athens, Georgia

Athens, officially Athens–Clarke County, is a consolidated city-county and college town in the U.S. state of Georgia. Athens lies about northeast of downtown Atlanta, and is a satellite city of the capital. The University of Georgia, the sta ...

. He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

in 1815, the same year he began to practice medicine in Georgia. Charles Meigs received his MD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1817, and that summer he moved his family—which now included one-year-old Montgomery—to Philadelphia and established a practice there. The Meigs family was wealthy and well-connected, and Charles Meigs was a strong supporter of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

. Meigs had extremely good memory, and his father instilled in him a sense of duty and a desire to pursue honorable causes. Young Montgomery received schooling at the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

(then a preparatory school for the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

). Meigs learned French, German, and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and studied art, literature, and poetry.Field, p. 74. He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania when he was only 15 years old.Miller, p. 6. A hard worker, he was one of the top students at the university.

The Meigs family had extensive ties to the military and to West Point, the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

. Montgomery Meigs, caught up in the nationalistic fervor of the time, wished to serve in the army. West Point was the only well established engineering school in the United States at the time.Herrin, p. 4. Through family connections, Meigs won an appointment to West Point, entering in 1832. He excelled in his studies at West Point, although he himself said he spent too much time at athletics and outdoor activities. He was among the top three students in French and mathematics, and did well in history. He graduated fifth out of a class of 49 in 1836, and he had more good conduct merits than two-thirds of his classmates.

He received a commission as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the 1st U.S. Artillery, but most of his army service was with the Corps of Engineers, in which he worked on important engineering projects.

In his early assignments, Meigs helped build Fort Mifflin

Fort Mifflin, originally called Fort Island Battery and also known as Mud Island Fort, was commissioned in 1771 and sits on Mud Island (or Deep Water Island) on the Delaware River below Philadelphia, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia International A ...

and Fort Delaware

Fort Delaware is a former harbor defense facility, designed by chief engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River.Dobbs, Kelli W., et al. During the American Civil War, the Union used Fort Delaware as ...

, both on the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock (village), New York, Hancock, New York, the river flows for along the borders of N ...

, and Fort Wayne

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

on the Detroit River

The Detroit River flows west and south for from Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie as a strait in the Great Lakes system. The river divides the metropolitan areas of Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario, Windsor, Ontario—an area collectively refe ...

. He also served under the command of then- Lt. Robert E. Lee to make navigational improvements on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

. Beginning in 1844, Meigs also was involved with the construction of Fort Montgomery on Lake Champlain

, native_name_lang =

, image = Champlainmap.svg

, caption = Lake Champlain-River Richelieu watershed

, image_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry =

, location = New York/Vermont in the United States; and Quebec in Canada

, coords =

, type =

, ...

in upstate New York.

His favorite prewar engineering project was the Washington Aqueduct

The Washington Aqueduct is an aqueduct that provides the public water supply system serving Washington, D.C., and parts of its suburbs, using water from the Potomac River. One of the first major aqueduct projects in the United States, the Aquedu ...

, which he supervised from 1852 to 1860. It involved the construction of the monumental Union Arch Bridge

The Union Arch Bridge, also called the "Cabin John Bridge", is a historic masonry structure in Cabin John, Maryland. It was designed as part of the Washington Aqueduct. The bridge construction began in 1857 and was completed in 1864. The roadw ...

across Cabin John Creek

Cabin John Creek is a tributary stream of the Potomac River in Montgomery County, Maryland. The watershed covers an area of . The headwaters of the creek originate in the city of Rockville, and the creek flows southward for U.S. Geological Surve ...

, designed by Alfred L. Rives, which for 50 years remained the longest single-span masonry arch in the world.

From 1853 to 1859, he also supervised the building of the wings and dome of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

and, from 1855 to 1859, the extension of the General Post Office Building.

In the fall of 1860, as a result of a disagreement over procurement contracts, Meigs incurred the ill will of the

In the fall of 1860, as a result of a disagreement over procurement contracts, Meigs incurred the ill will of the Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buchan ...

, and was banished to Tortugas in the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

to construct fortifications there and at Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

, including Fort Jefferson, Florida

Fort Jefferson is a massive but unfinished coastal fortress. It is the largest brick masonry structure in the Americas, and is composed of over 16 million bricks. The building covers . Among United States forts, only Fort Monroe in Virginia a ...

. Upon the resignation of Floyd a few months later, Meigs was recalled to his work on the aqueduct at Washington.

Civil War

Just before the outbreak of the Civil War, Meigs and Lt. Col. Erasmus D. Keyes were quietly charged byPresident

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

with drawing up a plan for the relief of Fort Pickens

Fort Pickens is a pentagonal historic United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. The fort was completed in 1834 and was one of the few ...

, Florida, by means of a secret expedition. In April 1861, together with Lieutenant David D. Porter of the Navy, they carried out the expedition, embarking under orders from the President without the knowledge of either the Secretary of the Navy or the Secretary of War.

On May 14, 1861, Meigs was appointed colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

, 11th U.S. Infantry, and on the following day, promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

and Quartermaster General of the Army. The previous Quartermaster General, Joseph Johnston Joseph Johnston may refer to:

*Joseph Johnston (Irish politician) (1890–1972), Irish academic, farmer and politician

*Allan Johnston (politician) (Joseph Allan Johnston, 1904–1974), Liberal party member of the Canadian House of Commons

* Joseph ...

, had resigned and become a general in the Confederate Army. Meigs established a reputation for being efficient, hard-driving, and scrupulously honest. He molded a large and somewhat diffuse department into a great tool of war. He was one of the first to fully appreciate the importance of logistical preparations in military planning, and under his leadership, supplies moved forward and troops were transported over long distances with ever-greater efficiency.

Of his work in the quartermaster's office, James G. Blaine remarked:

Montgomery C. Meigs, one of the ablest graduates of the Military Academy, was kept from the command of troops by the inestimably important services he performed as Quartermaster General. Perhaps in the military history of the world there never was so large an amount of money disbursed upon the order of a single man ... The aggregate sum could not have been less during the war than fifteen hundred million dollars, accurately vouched and accounted for to the last cent.Secretary of State William H. Seward's estimate was "that without the services of this eminent soldier the national cause must have been lost or deeply imperiled."

While Meigs served as Quartermaster General throughout the war he went on an extensive inspection tour from August 1863 to January 1864. During that time Colonel Charles Thomas acted in his stead back in Washington, D.C. Meigs' field services during the Civil War included command of

While Meigs served as Quartermaster General throughout the war he went on an extensive inspection tour from August 1863 to January 1864. During that time Colonel Charles Thomas acted in his stead back in Washington, D.C. Meigs' field services during the Civil War included command of Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's base of supplies at Fredericksburg and Belle Plain, Virginia

Belle Plains, Virginia (sometimes spelled as Belle Plain)The current name of the road leading to the area and the USGS-based National Mahereuse the "Belle Plains" spelling. was a steamboat landing and unincorporated settlement on the south bank of ...

(1864); command of a division of War Department employees in the defense of Washington at the time of Jubal A. Early's raid (July 11 to 14, 1864); personally supervising the refitting and supplying of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

's army at Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

(January 5 to 29, 1865), Goldsboro, and Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the List of North Carolina county seats, seat of Wake County, North Carolina, Wake County in the United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most ...

and reopening Sherman's lines of supply (March to April 1865). He was brevetted

In many of the world's military establishments, a brevet ( or ) was a warrant giving a commissioned officer a higher rank title as a reward for gallantry or meritorious conduct but may not confer the authority, precedence, or pay of real rank. ...

to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on July 5, 1864.

A staunch Unionist, Meigs detested the Confederacy. His feelings led directly to the establishment of Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

. On July 16, 1862, Congress passed legislation authorizing the U.S. federal government to purchase land for national cemeteries for military dead, and put the U.S. Army Quartermaster General in charge of this program. The Soldiers' Home in Washington, D.C., and the Alexandria Cemetery were the primary burying grounds for war dead in the D.C. area, but by late 1863 both cemeteries were full.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 84.Accessed 2012-05-03. In May 1864, Union forces suffered large numbers of dead in the

Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the American Civil War. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General Robert E. Lee and the Confederate Arm ...

. Meigs ordered that an examination of eligible sites be made for the establishment for a large new national military cemetery. Within weeks, his staff reported that Arlington Estate was the most suitable property in the area. The property was high and free from floods (which might unearth graves), it had a view of the District of Columbia, and it was aesthetically pleasing. It was also the home of Robert E. Lee, future General-in-Chief of the Confederacy, and denying Lee use of his home after the war was a valuable political consideration.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 88.Accessed 2012-05-03. Although the first military burial at Arlington had been made on May 13,Cultural Landscape Program, p. 86.

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs did not authorize establishment of burials until June 15, 1864.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 85.

Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs ordered that the estate be surveyed and that be set aside for use as a cemetery.

The logistics system

While the Confederacy never had enough supplies and it kept getting worse, the Union forces typically had enough food, supplies, ammunition and weapons. The Union supply system, even as it penetrated deeper into the South, maintained its efficiency. Historians credit the achievements to Meigs. Union quartermasters were responsible for most of the $3 billion spent for the war. They operated out of sixteen major depots, which formed the basis of the system of procurement and supply throughout the war. As the war expanded, operation of these depots became much more complex, with an overlapping and interweaving relationship between the army and government operated factories, private factories, and numerous middlemen. The purchase of goods and services through contracts supervised by the quartermasters accounted for most of federal military expenditures, apart from the wages of the soldiers. The quartermasters supervised their own soldiers, and cooperated closely with state officials, manufacturers and wholesalers trying to sell directly to the army; and representatives of civilian workers looking for higher pay at government factories. The complex system was closely monitored by congressmen anxious to ensure that their districts won their share of contracts. The system grew in efficiency to the point Union troops on long marches would simply throw away excess knapsacks, bedrolls, overcoats, and other pieces of clothing and equipment that they felt were weighing them down, fully confident that they would be resupplied at some point in the near future.Wartime deaths

In October 1864, his son, 1st Lieutenant John Rodgers Meigs, was killed at Swift Run Gap in Virginia and was buried at a Georgetown Cemetery. Lt. Meigs was part of a three-man patrol which ran into a three-man Confederate patrol. Lt. Meigs was killed, one man was captured, and one man escaped. To the end of his life, Meigs believed that his son had been murdered after being captured—despite evidence to the contrary. The younger Meigs was laid to rest in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown in Washington, D.C. Both Abraham Lincoln andSecretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

attended the interment. He was later re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Meigs was also present for Lincoln's death. At 10:00 pm on the evening of April 14, 1865, Meigs heard that William Seward had been attacked by a knife-wielding assailant. Meigs rushed to Rodgers House, Seward's home on Lafayette Square just across the street from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

. Shortly after arriving at Seward's home, Meigs learned of the shooting of Lincoln. He rushed to the Petersen House

The Petersen House is a 19th-century federal style row house located at 516 10th Street NW in Washington, D.C. On April 15, 1865, United States President Abraham Lincoln died there after being shot the previous evening at Ford's Theatre, locat ...

across from Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in August 1863. The theater is infamous for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater box ...

, where Lincoln lay dying. Meigs stood at the front door of the house for the rest of the deathwatch. He alone decided who was admitted to the house. When Lincoln died at 7:22 am on April 15, Meigs moved into the parlor to sit with the president's body. During Lincoln's funeral procession in the city five days later, Meigs rode at the head of two battalions of quartermaster corps soldiers.

Role in developing Arlington National Cemetery

Meigs played a critical role in developing Arlington National Cemetery, both during the Civil War and afterward.

Although most burials initially occurred near the freedmen's cemetery in the estate's northeast corner, in mid-June 1864 Meigs ordered that burials commence immediately on the grounds of

Meigs played a critical role in developing Arlington National Cemetery, both during the Civil War and afterward.

Although most burials initially occurred near the freedmen's cemetery in the estate's northeast corner, in mid-June 1864 Meigs ordered that burials commence immediately on the grounds of Arlington House Arlington House may refer to:

*Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial

*Arlington House (London) a hostel for the homeless in London, England, and one of the Rowton Houses

*Arlington House, Margate, an eighteen-storey residential apartment bloc ...

. Brigadier General René Edward De Russy

René Edward De Russy (February 22, 1789 – November 23, 1865) was an engineer, military educator, and career United States Army officer who was responsible for constructing many Eastern United States coastal fortifications, as well as some fort ...

was living in Arlington House at the time and opposed the burial of bodies close to his quarters, forcing new interments to occur far to the west (in what is now Section 1 of the cemetery). But Meigs still demanded that officers be buried on the grounds of the mansion, around the Lees' former flower garden. The first officer burial had occurred there on May 17, but with Meigs' order another 44 officers were buried along the southern and eastern sides within a month. By May 31, more than 2,600 burials had occurred in the cemetery, and Meigs ordered that a white picket fence be constructed around the burial grounds. In December 1865, Robert E. Lee's brother, Smith Lee, visited Arlington House and observed that the house could be made livable again if the graves around the flower garden were removed.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 87.Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs hated Lee for betraying the Union, and ordered that more burials occur near the house to make it politically impossible for disinterment to occur. Meigs himself designed and implemented most of the changes at the cemetery in the 15 years after the war. In 1865, for example, Meigs decided to build a monument to Civil War dead in the center of a grove of trees west of the Lee's flower garden.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 96.

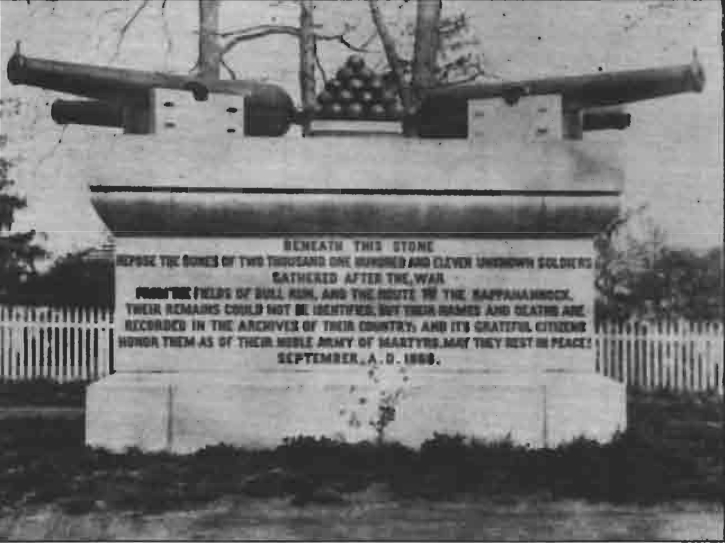

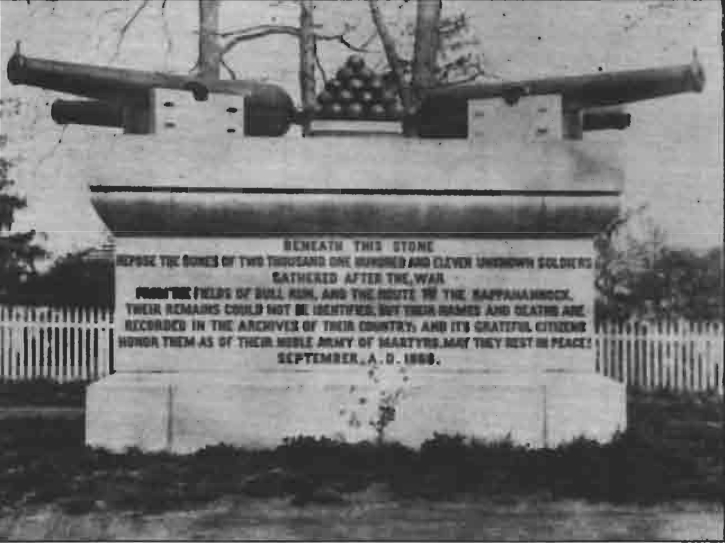

Accessed 2012-04-29. U.S. Army troops were dispatched to investigate every battlefield within a radius of the city of Washington, D.C. The bodies of 2,111 Union and Confederate dead were collected, most of them from the battlefields of

First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederat ...

, as well as the Union army's retreat along the Rappahannock River

The Rappahannock River is a river in eastern Virginia, in the United States, approximately in length.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 1, 2011 It traverses the entir ...

(which occurred after both battles). Although Meigs had not intended to collect the remains of Confederate war dead, the inability to identify remains meant that both Union and Confederate dead were interred below the cenotaph. U.S. Army engineers chopped down most of the trees and dug a circular pit about wide and deep into the earth. The walls and floor were lined with brick, and it was segmented it into compartments with mortared brick walls. Into each compartment were placed a different body part: skulls, legs, arms, ribs, etc. The vault was half full by the time it was ready for sealing in September 1866. Meigs designedPoole, p. 87. a tall, long, wide grey granite and concrete cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

to rest on top of the burial vault. The Civil War Unknowns Monument

The Civil War Unknowns Monument is a burial vault and memorial honoring unidentified dead from the American Civil War. It is located in the grounds of Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Vir ...

consists of two long, light grey granite slabs, with the shorter ends formed by sandwiching a smaller slab between the longer two. On the west face was an inscription describing the number of dead in the vault below, and honoring the "unknowns of the Civil War". Originally, a Rodman gun

Drawing comparing Model 1844 8-inch columbiad and Model 1861 10-inch "Rodman" columbiad. The powder chamber on the older columbiad is highlighted by the red box.

The Rodman gun is any of a series of American Civil War–era columbiads designed by ...

was placed on each corner, and a pyramid of shot adorned the center of the lid. A circular walk, centered from the center of the memorial, provided access. A walk led east to the flower garden, and another west to the road. Sod was laid around the memorial, and planting beds filled with annual plant

An annual plant is a plant that completes its life cycle, from germination to the production of seeds, within one growing season, and then dies. The length of growing seasons and period in which they take place vary according to geographical ...

s emplaced.

McClellan Gate

The McClellan Gate (sometimes known as the McClellan Arch) is a memorial to Major General George B. McClellan located inside Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, in the United States. Constructed about 1871 on Arlington Rid ...

constructed. Located just west of the intersection of what is today McClellan and Eisenhower Drives, this was originally Arlington National Cemetery's main gate. Built of red sandstone and red brick, the name "MCCLELLAN" tops the simple rectangular gate in gilt letters. But just below the name was inscribed the name "MEIGS"—a tribute to himself which Meigs could not help making.Poole, p. 89. Due to the growing importance of the cemetery as well as the much larger crowds attending Memorial Day observances, Meigs also decided a formal meeting space at the cemetery was needed. A grove of trees southwest of Arlington House was cut down, and an amphitheater (today known as the Tanner Amphitheater

The James Tanner Amphitheater is a historic wood and brick amphitheater located at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, in the United States. The amphitheater, which was originally unnamed, was constructed in 1873 and served ...

) was constructed in 1874.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 108.Accessed 2012-05-03. Meigs himself designed the amphitheater. Meigs continued to work to ensure that the Lee family could never take control of Arlington. In 1882, the

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

ruled in '' United States v. Lee'' that the seizure of the Arlington estate at a tax sale by the United States was illegal, and returned the estate to George Washington Custis Lee

George Washington Custis Lee (September 16, 1832 – February 18, 1913), also known as Custis Lee, was the eldest son of Robert E. Lee and Mary Anna Custis Lee. His grandfather George Washington Custis was the step-grandson and adopted son of G ...

, General Lee's oldest son.Poole, 2009, p. 55. He, in turn, sold the estate back to the U.S. government for $150,000 in 1883. To commemorate the retention of the estate, in 1884 Meigs ordered that a Temple of Fame be erected in the Lee flower garden. The U.S. Patent Office building had suffered a massive fire in 1877. It was torn down and rebuilt in 1879, but the work went very slowly. Meigs ordered that stone columns, pediment

Pediments are gables, usually of a triangular shape.

Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the lintel, or entablature, if supported by columns. Pediments can contain an overdoor and are usually topped by hood moulds.

A pedimen ...

s, and entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

s which had been saved from the Patent Office be used to construct the Temple of Fame. The Temple was a round, Greek Revival

The Greek Revival was an architectural movement which began in the middle of the 18th century but which particularly flourished in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, predominantly in northern Europe and the United States and Canada, but ...

, temple-like structure with Doric columns

The Doric order was one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of col ...

supporting a central dome. Inscribed on the pediment supporting the dome were the names of great Americans such as George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, Ulysses S. Grant, Abraham Lincoln, and David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 – August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first rear admiral, vice admiral, and admiral in the United States Navy. Fa ...

. A year after it was built, the names of Union Civil War generals were carved into its columns.Cultural Landscape Program, p. 122.Accessed 2012-05-03. Since not enough marble was available to rebuild the dome, a tin dome (molded and painted to look like marble) was installed, instead. The Temple of Fame was demolished in 1967.

Postbellum career and death

Meigs became a permanent resident of the District of Columbia after the war. He purchased a home located at 1239 Vermont Avenue NW (at the corner of Vermont Avenue and N Street).

As Quartermaster General after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (constructed between 1866 and 1867), the

Meigs became a permanent resident of the District of Columbia after the war. He purchased a home located at 1239 Vermont Avenue NW (at the corner of Vermont Avenue and N Street).

As Quartermaster General after the Civil War, Meigs supervised plans for the new War Department building (constructed between 1866 and 1867), the National Museum

A national museum is a museum maintained and funded by a national government. In many countries it denotes a museum run by the central government, while other museums are run by regional or local governments. In other countries a much greater numb ...

(constructed in 1876), the extension of the Washington Aqueduct (constructed in 1876), and for a hall of records (constructed in 1878). Along with fellow Quartermaster Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Roeliff Brinkerhoff, Meigs edited a volume entitled, ''The Volunteer Quartermaster'', a treatise which was considered the standard guide for the officers and employees of the quartermaster's department up until World War I.

From 1866 to 1868, to recuperate from the strain of his war service, Meigs visited Europe. From 1875 to 1876, he made another visit to study the organization of European armies, this time with nephew and Army officer Montgomery M. Macomb

Montgomery Meigs Macomb (October 12, 1852 – January 19, 1924) was a United States Army Brigadier General. He was a veteran of the Spanish–American War and World War I, and was notable for serving as commander of the Hawaiian Department, the A ...

assigned as '' aide-de-camp''. After his retirement on February 6, 1882, he was succeeded by Daniel H. Rucker and became architect of the Pension Office Building, now home to the National Building Museum

The National Building Museum is located at 401 F Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is a museum of "architecture, design, engineering, construction, and urban planning". It was created by an act of Congress in 1980, and is a private Non-profit org ...

. He was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

, a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, a co-founder of the Philosophical Society of Washington

Founded in 1871, the Philosophical Society of Washington is the oldest scientific society in Washington, D.C. It continues today as PSW Science.

Since 1887, the Society has met regularly in the assembly hall of the Cosmos Club. In the Club's pr ...

, and one of the earliest members of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

.

Pension Building (1882 to 1887)

Following the end of the Civil War, the US Congress passed legislation that greatly extended the scope of pension coverage for both veterans and their survivors and dependents, notably their widows and orphans. This greatly increased the number of staff needed to administer the new benefits system. More than 1,500 clerks were required, and a new building was needed to house them. Meigs was chosen to design and construct the new building, now theNational Building Museum

The National Building Museum is located at 401 F Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is a museum of "architecture, design, engineering, construction, and urban planning". It was created by an act of Congress in 1980, and is a private Non-profit org ...

. He broke away from the established Greco-Roman models that had been the basis of government buildings in Washington, D.C., until then, and was to continue following the completion of the Pension Building. Meigs based his design on Italian Renaissance precedents, notably Rome's Palazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance List of palaces in Italy#Rome, palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and cur ...

and Palazzo della Cancelleria.

Caspar Buberl

Caspar Buberl (1834 – August 22, 1899) was an American sculptor. He is best known for his Civil War monuments, for the terra cotta relief panels on the Garfield Memorial in Cleveland, Ohio (depicting the various stages of James Garfield' ...

. Since creating a work of sculpture of that size was well out of Meigs's budget, he had Buberl create 28 different scenes (totaling in length), which were then mixed and slightly modified to create the continuous long parade that includes over 1,300 figures. Because of the way the 28 sections are modified and mixed up, only somewhat careful examination reveals the frieze to be the same figures repeated over and over. The sculpture includes infantry, navy, artillery, cavalry, and medical components, as well as a good deal of the supply and quartermaster functions. Meigs's correspondence with Buberl reveals that Meigs insisted that one teamster, "must be a negro, a plantation slave, freed by war," be included in the quartermaster panel. This figure was ultimately to assume a position in the center, over the west entrance to the building.

When Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

was asked to comment on the building, his reply echoed the sentiment of many of the Washington establishment of the day, that the only thing that he could find wrong with the building was that it was fireproof. (A similar quote is also attributed to William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, so the story might well be apocryphal.) The completed building, sometimes referred to as "Meigs's Old Red Barn", was created by using more than 15,000,000 bricks, which, according to the wits of the day, were all counted by the parsimonious Meigs.

Death

Meigs contracted acold

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is absolute zero, defined as 0.00K on the Kelvin scale, an absolute thermodynamic ...

on December 27, 1891. Within a few days, it turned into pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

. Meigs died at home at 5:00 pm on January 2, 1892. His body was interred with high military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. General orders issued at the time of his death declared, "the Army has rarely possessed an officer ... who was entrusted by the government with a great variety of weighty responsibilities, or who proved himself more worthy of confidence."

Family

In 1841, Meigs married Louisa Rodgers (1816–1879), the daughter of CommodoreJohn Rodgers John Rodgers may refer to:

Military

* John Rodgers (1728–1791), colonel during the Revolutionary War and owner of Rodgers Tavern, Perryville, Maryland

* John Rodgers (naval officer, born 1772), U.S. naval officer during the War of 1812, first ...

. Their children included:

* John Rodgers Meigs (1842–1864), a West Point graduate and Army officer who was killed in action during the Civil War

*Mary Montgomery Meigs (1843–1930), the wife of Army officer Joseph Hancock Taylor, who was the son of Union Army Brigadier General Joseph Pannell Taylor

Joseph Pannell Taylor (May 4, 1796 – June 29, 1864) was a career United States Army officer and Union general in the American Civil War. He was the younger brother of Zachary Taylor, the 12th President of the United States.

Early life

He wa ...

, and nephew of President Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

*Charles Delucena Meigs (1845–1853), who was named for Meigs' father

* Montgomery Meigs (1847–1931), a civil engineer who enjoyed a long career in railroad, bridge, canal, power plant, and road construction

*Vincent Trowbridge Meigs (1851–1853)

*Louisa Rodgers Meigs (1854–1922), the wife of British journalist Archibald Forbes

Honors

*General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Meigs was inducted into the Quartermaster Hall of Fame in its charter year of 1986.

*In 2012, the Georgia Historical Society

The Georgia Historical Society (GHS) is a statewide historical society in Georgia. Headquartered in Savannah, Georgia, GHS is one of the oldest historical organizations in the United States. Since 1839, the society has collected, examined, and tau ...

erected a historical marker

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other ...

at the birthplace of Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs in Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

.

* Camp Meigs, in Readville

Readville is part of the Hyde Park neighborhood of Boston. Readville's ZIP Code is 02136. It was called Dedham Low Plains from 1655 until it was renamed after the mill owner James Read in 1847. It was part of Dedham until 1867. It is served by ...

, Massachusetts was named after him.

Ships

*''General Meigs'', a Quartermaster Corps passenger and freight steamer built in 1892 and serving in the early 20th century. *, an Army transport ship sunk atDarwin, Northern Territory

Darwin ( ; Larrakia: ) is the capital city of the Northern Territory, Australia. With an estimated population of 147,255 as of 2019, the city contains the majority of the residents of the sparsely populated Northern Territory.

It is the smalle ...

.

*, a troop transport launched in 1944, serving in WWII and Korea.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

References

Bibliography

*Atkinson, Rick. ''Where Valor Rests: Arlington National Cemetery.'' Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2007. *Bednar, Michael J. ''L' Enfant's Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, D.C.'' Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. *Browning, Charles Henry. ''Americans of Royal Descent.'' Baltimore, Md.: Genealogical Publishing, 1911.Cultural Landscape Program. ''Arlington House: The Robert E. Lee Memorial Cultural Landscape Report.'' National Capital Region. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: 2001.

* Dickinson, William C. and Dean A. Herrin. ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital'' (2002) * East, Sherrod E. "Montgomery C. Meigs and the Quartermaster Department." ''Military Affairs'' (1961): 183–196. in JSTOR*Eicher, John H. and Eicher, David J. ''Civil War High Commands.'' Palo Alto, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2001, . *Farwell, Byron. ''The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare.'' New York: Norton, 2001. *Field, Cynthia R. "A Rich Repast of Classicism: Meigs and Classical Sources." In ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital.'' William C Dickinson, Dean A Herrin, and Donald R Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001. * Freeman, Douglas S.br>''R. E. Lee, A Biography''

4 vol. New York: Scribners, 1934. *Hannan, Caryn, ed. ''Georgia Biographical Dictionary.'' Vol. 1. Hamburg, Mich.: State History Publications, 2008. *Herrin, Dean A. "The Eclectic Engineer: Montgomery C. Meigs and His Engineering Projects." In ''Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital.'' William C Dickinson, Dean A Herrin, and Donald R Kennon, eds. Athens, Ohio: United States Capitol Historical Society, 2001. *Holt, Dean W. ''American Military Cemeteries.'' Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2010. *Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs and Ware, Thomas Clayton. ''Theodore O'Hara: Poet-Soldier of the Old South.'' Lexington, Ky.: University of Tennessee Press, 1998. *McDaniel, Joyce L. ''The Collected Works of Caspar Buberl: An Analysis of a Nineteenth Century American Sculptor'' Master's Thesis. Wellesley University, 1976. *Miller, David W. ''Second Only to Grant: Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs.'' Shippensburg, Pa.: White Maine Books, 2000. *Morton, Thomas G. ''The History of the Pennsylvania Hospital, 1751-1895.'' Philadelphia: Times Printing House, 1895. *Peters, James Edward. ''Arlington National Cemetery, Shrine to America's Heroes.'' Bethesda, Md.: Woodbine House, 2000. *Poole, Robert M. ''On Hallowed Ground: The Story of Arlington National Cemetery.'' New York: Walker, 2009. * *Schama, Simon. ''The American Future: A History.'' New York: Ecco, 2009. *Scott, Pamela and Lee, Antoinette J. ''Buildings of the District of Columbia'', Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. *Ulbrich, David. "Montgomery Cunningham Meigs." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History.'' David S. Heidler, and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . *Weigley, Russell F

''Quartermaster General of the Union Army: A Biography of M.C. Meigs.''

New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. *Wilson, Mark R. ''The Business of Civil War: Military Mobilization and the State, 1861-1865.'' Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. *Wolff, Wendy, ed. ''Capitol Builder: The Shorthand Journals of Montgomery C. Meigs.'' Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001.

External links

*National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

at

Hagley Museum and Library

The Hagley Museum and Library is a nonprofit educational institution in unincorporated New Castle County, Delaware, near Wilmington. Covering more than along the banks of the Brandywine Creek, the museum and grounds include the first du Pont ...

Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, U.S.A. historical marker – Georgia Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Meigs, Montgomery C. 1816 births 1892 deaths 19th-century American architects Architects of the Capitol Burials at Arlington National Cemetery Logistics personnel of the United States military Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War People from Augusta, Georgia Quartermasters General of the United States Army Southern Unionists in the American Civil War Union Army generals United States Military Academy alumni