Monroe Doctrine Centennial half dollar on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Monroe Doctrine Centennial half dollar was a fifty-cent piece struck by the United States Bureau of the Mint. Bearing portraits of former U.S. Presidents

By 1922, the Hollywood film industry was in serious trouble. Established in the Los Angeles area during the 1910s after moving from such eastern venues as

By 1922, the Hollywood film industry was in serious trouble. Established in the Los Angeles area during the 1910s after moving from such eastern venues as

The fair organizers did not await congressional approval to begin planning the coin. According to Swiatek and Breen, the fair's director general Frank B. Davison came up with the concept for the designs. On December 7, 1922, Commission of Fine Arts chairman Charles Moore wrote to Buffalo nickel designer and sculptor member of the commission James Earle Fraser, "The Los Angeles people are planning to celebrate the Monroe Doctrine Centennial. They are going to have a 50-cent piece and have decided that on the obverse shall be the heads of President Monroe and John Quincy Adams ... On the reverse will be the western continents from Hudson Bay to Cape Horn with some dots for the West Indies and some indication of the Panama Canal ... It strikes me that the designs having been settled upon, the lastermodels could be worked out quite readily and that a pretty swell thing could be made."

Fraser contacted fellow New York sculptor

The fair organizers did not await congressional approval to begin planning the coin. According to Swiatek and Breen, the fair's director general Frank B. Davison came up with the concept for the designs. On December 7, 1922, Commission of Fine Arts chairman Charles Moore wrote to Buffalo nickel designer and sculptor member of the commission James Earle Fraser, "The Los Angeles people are planning to celebrate the Monroe Doctrine Centennial. They are going to have a 50-cent piece and have decided that on the obverse shall be the heads of President Monroe and John Quincy Adams ... On the reverse will be the western continents from Hudson Bay to Cape Horn with some dots for the West Indies and some indication of the Panama Canal ... It strikes me that the designs having been settled upon, the lastermodels could be worked out quite readily and that a pretty swell thing could be made."

Fraser contacted fellow New York sculptor

The faint lines in the field around the continents represent various ocean currents, with the

The faint lines in the field around the continents represent various ocean currents, with the

The American Historical Revue and Motion Picture Industry Exposition was open from July 2 to August 4, 1923. The fair was located off of Figueroa Street in Exposition Park, just to the east of the brand-new

The American Historical Revue and Motion Picture Industry Exposition was open from July 2 to August 4, 1923. The fair was located off of Figueroa Street in Exposition Park, just to the east of the brand-new

James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

and John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, the coin was issued in commemoration of the centennial of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

and was produced at the San Francisco Mint

The San Francisco Mint is a branch of the United States Mint. Opened in 1854 to serve the gold mines of the California Gold Rush, in twenty years its operations exceeded the capacity of the first building. It moved into a new one in 1874, now kno ...

in 1923. Sculptor Chester Beach

Chester A. Beach (May 23, 1881 – August 6, 1956) was an American sculptor who was known for his busts and medallic art.

Early life

Beach was born in San Francisco, California. He studied initially at the California School of Mechanical Art ...

is credited with the design, although the reverse closely resembles an earlier work by Raphael Beck.

In 1922, the motion picture industry was faced with a number of scandals, including manslaughter charges against star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle (; March 24, 1887 – June 29, 1933) was an American silent film actor, comedian, director, and screenwriter. He started at the Selig Polyscope Company and eventually moved to Keystone Studios, where he worked w ...

. Although Arbuckle was eventually acquitted, motion picture executives sought ways of getting good publicity for Hollywood. One means was an exposition, to be held in Los Angeles in mid-1923. To induce Congress to issue a commemorative coin as a fundraiser for the fair, organizers associated the exposition with the 100th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine, and legislation for a commemorative half dollar for the centennial was passed.

The exposition was a financial failure. The coins did not sell well, and the bulk of the mintage of over 270,000 was released into circulation. Beach faced accusations of plagiarism because of the similarity of the reverse design to a work by Beck, though he and fellow sculptor James Earle Fraser denied any impropriety. Many of the pieces that had been sold at a premium and saved were spent during the Depression; most surviving coins show evidence of wear.

Background

In the early 1820s, the United States deemed two matters untoward interference by European powers in its zone of influence. The first was the RussianUkase of 1821

The Ukase of 1821 (russian: Указ 1821 года) was a Russian proclamation (a ''ukase'') of territorial sovereignty over northwestern North America, roughly present-day Alaska and most of the Pacific Northwest. The ''ukase'' was declared on Se ...

, asserting exclusive territorial and trading rights along much of what is today Canada's Pacific coast. The United States considered this area to be part of the Oregon Country

Oregon Country was a large region of the Pacific Northwest of North America that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom and the United States in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818, co ...

and hoped to eventually gain control of it. The second was possible European threats against the Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

n nations, newly independent from Spain. United States officials feared that a Quadruple Alliance of Prussia, Austria, Russia, and France would restore Spain to power in the Americas.

British foreign minister

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

George Canning

George Canning (11 April 17708 August 1827) was a British Tory statesman. He held various senior cabinet positions under numerous prime ministers, including two important terms as Foreign Secretary, finally becoming Prime Minister of the Uni ...

was concerned that in the event of a Spanish restoration in Latin America, his nation would lose the ability to trade there, which it had gained since the Spanish had been ousted. In 1823, he proposed to the American minister to Great Britain, Richard Rush

Richard Rush (August 29, 1780 – July 30, 1859) was the 8th United States Attorney General and the 8th United States Secretary of the Treasury. He also served as John Quincy Adams's running mate on the National Republican ticket in 1828.

Born ...

, that their two nations issue a joint statement against the retaking of the former Spanish colonies by force. Rush asked for instructions from President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

. The President consulted with his predecessors, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

, who favored the joint statement, as an alliance with Britain would protect the United States. Nevertheless, Monroe's Secretary of State, future president John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, felt that if the United States was going to set forth its principles, it should speak for itself and not seem to be following the lead of Britain. Accordingly, Rush was instructed to decline the opportunity to enter into a joint statement, although he was to inform the British that the two nations agreed on most issues.

The policy which would, some 30 years later, come to be called the "Monroe Doctrine" was contained in the President's annual message to Congress on December 2, 1823. It warned European nations against new colonial ventures in the Americas, and against interference with Western Hemisphere governments. The doctrine had little practical effect at the time, as the United States lacked the ability to enforce it militarily and most European powers ignored it, considering it beneath their dignity even to respond to such a proclamation. When several European powers dispatched men to settle land in the Guianas

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France ...

in the 1830s, the United States did not issue a formal protest. The Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

of 1846–1848 (and the resulting Mexican Cession

The Mexican Cession ( es, Cesión mexicana) is the region in the modern-day southwestern United States that Mexico originally controlled, then ceded to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 after the Mexican–American W ...

) increased Latin American suspicions over the doctrine, as many south of the border felt that the American purpose in warning European powers to keep out was to acquire the land for itself. Nevertheless, the Monroe Doctrine became an important part of United States foreign policy in the second half of the 19th and into the 20th century.

Inception

By 1922, the Hollywood film industry was in serious trouble. Established in the Los Angeles area during the 1910s after moving from such eastern venues as

By 1922, the Hollywood film industry was in serious trouble. Established in the Los Angeles area during the 1910s after moving from such eastern venues as Fort Lee, New Jersey

Fort Lee is a borough at the eastern border of Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey, situated along the Hudson River atop the Palisades.

As of the 2020 U.S. census, the borough's population was 40,191. As of the 2010 U.S. census, t ...

, the industry had been rocked by a number of scandals. These included the mysterious shooting death of film director William Desmond Taylor

William Desmond Taylor (born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner, 26 April 1872 – 1 February 1922) was an Anglo-Irish-American film director and actor. A popular figure in the growing Hollywood motion picture colony of the 1910s and early 1920s, ...

, and the subsequent evasive testimony concerning it by actress Mabel Normand

Amabel Ethelreid Normand (November 9, 1893 – February 23, 1930), better known as Mabel Normand, was an American silent film actress, screenwriter, director, and producer. She was a popular star and collaborator of Mack Sennett in their ...

, which helped destroy her career. Another notorious scandal of the early 1920s was the death of actress Virginia Rappe

Virginia Caroline Rappe (; July 7, 1891 – September 9, 1921) was an American model and silent film actress. Working mostly in bit parts, Rappe died after attending a party with actor Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, who was accused of manslaughter a ...

following an orgy at a San Francisco hotel. Actor Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle

Roscoe Conkling "Fatty" Arbuckle (; March 24, 1887 – June 29, 1933) was an American silent film actor, comedian, director, and screenwriter. He started at the Selig Polyscope Company and eventually moved to Keystone Studios, where he worked w ...

was, after three trials, acquitted of manslaughter, but the negative publicity ended his career as well. These scandals, together with the death of romantic lead Wallace Reid

William Wallace Halleck Reid (April 15, 1891 – January 18, 1923) was an American actor in silent film, referred to as "the screen's most perfect lover". He also had a brief career as a racing driver.

Early life

Reid was born in St. Louis, M ...

from a drug overdose and a number of instances of onscreen sexual explicitness, led to nationwide calls for a boycott of Hollywood films.

Film moguls sought means of damage control. They hired former Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsib ...

Will H. Hays

William Harrison Hays Sr. (; November 5, 1879 – March 7, 1954) was an American Republican politician.

As chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1918–1921, Hays managed the successful 1920 presidential campaign of Warren G. H ...

as censor to the industry; the Hays Code would govern how explicit a motion picture could be for decades to come. Another idea was an exposition and film festival to give good publicity to the industry, with the profits to be used for the making of educational films. Planning for this fair, to be held in Los Angeles in mid-1923, began in 1922. As other fairs, such as the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

and the Panama–Pacific Exposition, had procured the issuance of commemorative coins as a fundraiser, organizers sought a piece for the film fair. The city of Los Angeles wanted to use the fair to show it had come of age, as had Chicago for the Columbian Exposition and San Francisco with the Panama-Pacific event.

Realizing that Congress might not pass legislation for a coin to commemorate a film industry celebration, the organizers sought a historical event with a major anniversary to occur in 1923, which could be honored both at the fair and on the coin. The obvious candidate was the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

of 1773, but according to numismatists Anthony Swiatek and Walter Breen

Walter Henry Breen Jr. (September 5, 1928 – April 27, 1993) was an American numismatist, writer, and convicted child sex offender; as well as the husband of author Marion Zimmer Bradley. He was known among coin collectors for writing ''Wa ...

in their volume on U.S. commemorative coins, that episode "could not be tortured into even the vaguest relevance to California, let alone to Los Angeles". On December 18, 1922, California Congressman Walter Franklin Lineberger introduced a bill to strike a half dollar in commemoration of the centennial of the Monroe Doctrine, with the Los Angeles Clearing House (an association of banks) given the exclusive right to purchase the pieces from the government at face value. Lineberger claimed that Monroe's declaration had kept California, then owned by Mexico, out of the hands of European powers. The bill was questioned in the House of Representatives by Michigan Congressman Louis Cramton, and in the Senate by Vermont's Frank Greene, who stated, "it seems to me that the question is not one of selling a coin at a particular value or a particular place. The question is whether the United States government is going to go on from year to year submitting its coinage to this—well—harlotry." Despite these objections, the bill was enacted on January 24, 1923; a mintage of 300,000 pieces was authorized.

Preparation

The fair organizers did not await congressional approval to begin planning the coin. According to Swiatek and Breen, the fair's director general Frank B. Davison came up with the concept for the designs. On December 7, 1922, Commission of Fine Arts chairman Charles Moore wrote to Buffalo nickel designer and sculptor member of the commission James Earle Fraser, "The Los Angeles people are planning to celebrate the Monroe Doctrine Centennial. They are going to have a 50-cent piece and have decided that on the obverse shall be the heads of President Monroe and John Quincy Adams ... On the reverse will be the western continents from Hudson Bay to Cape Horn with some dots for the West Indies and some indication of the Panama Canal ... It strikes me that the designs having been settled upon, the lastermodels could be worked out quite readily and that a pretty swell thing could be made."

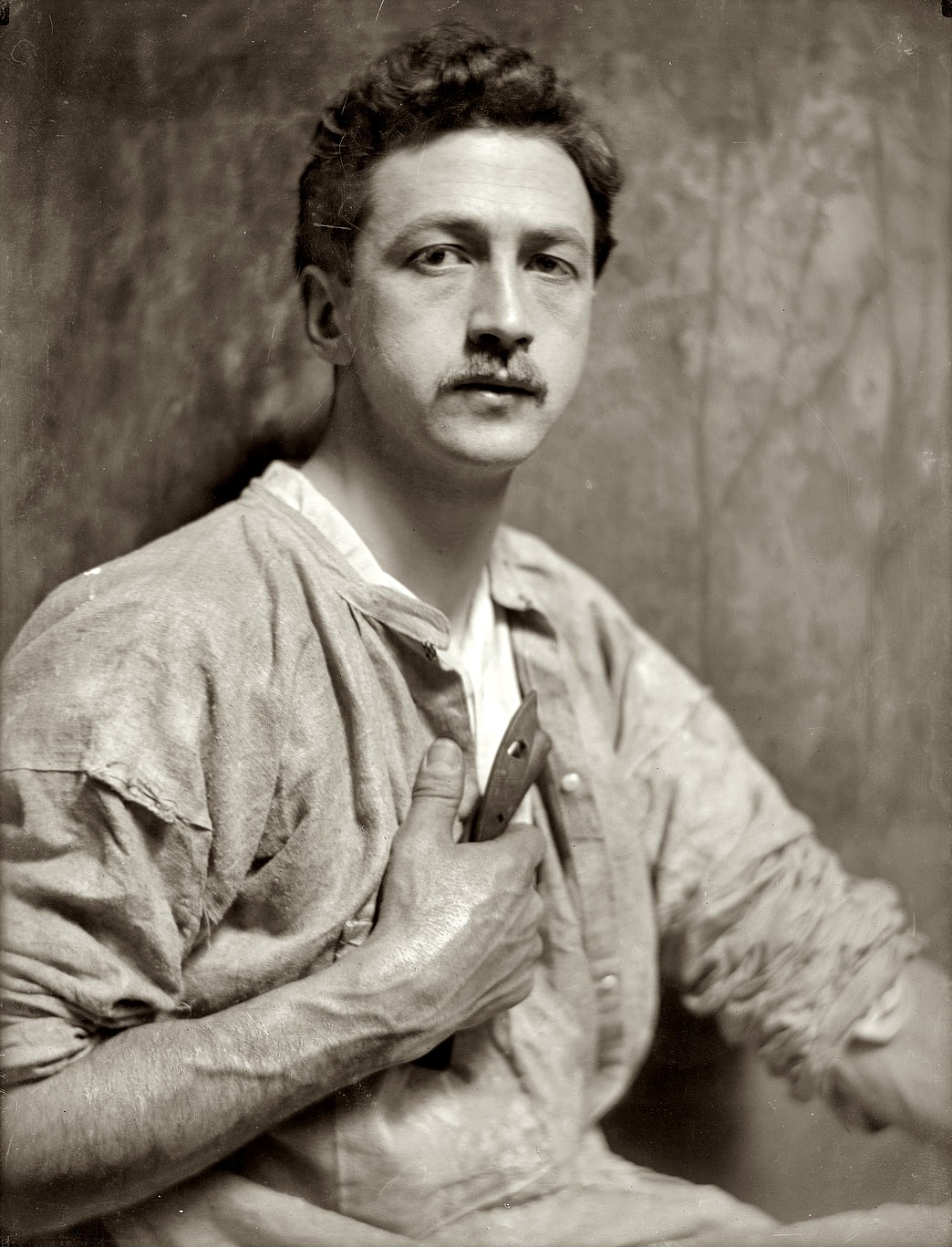

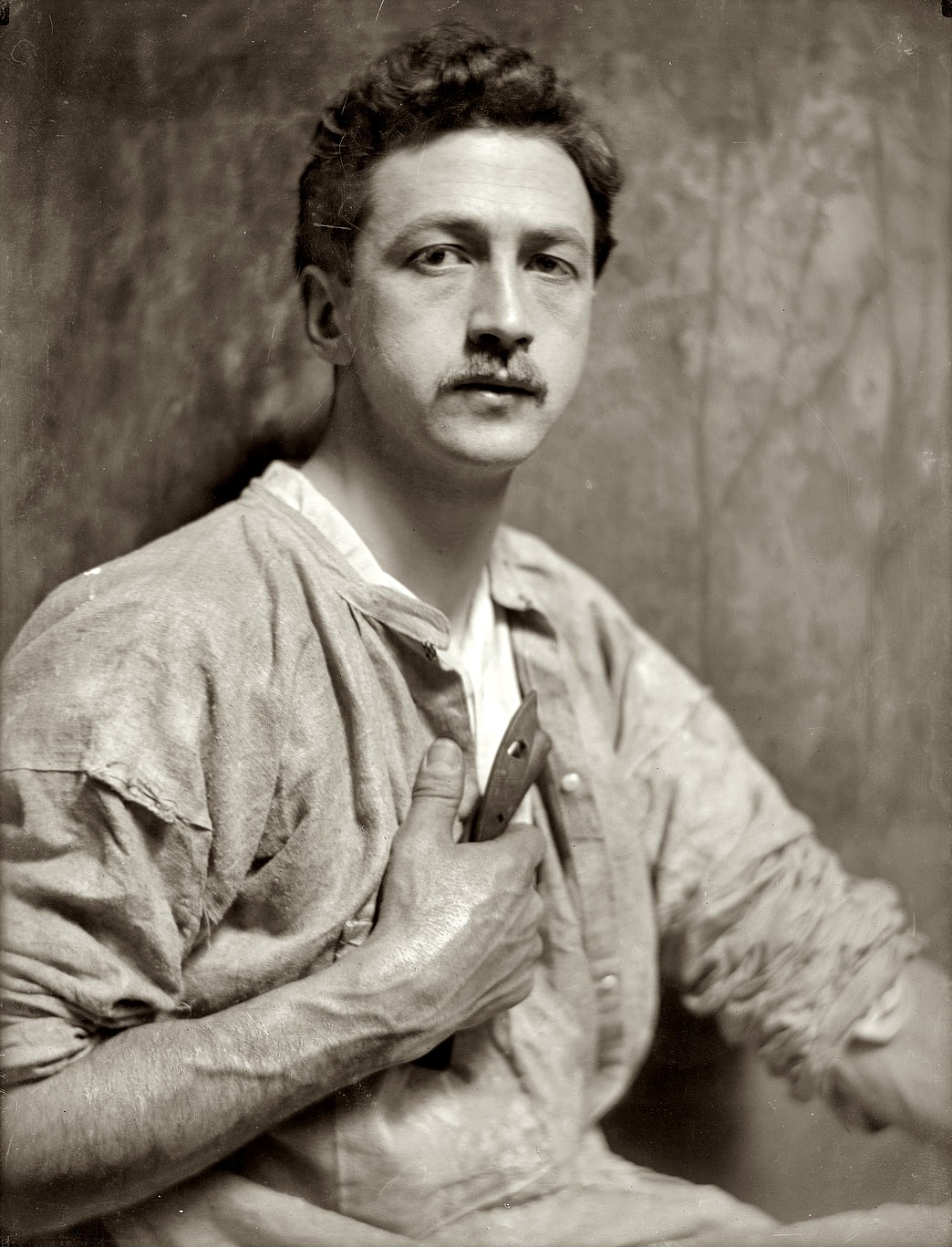

Fraser contacted fellow New York sculptor

The fair organizers did not await congressional approval to begin planning the coin. According to Swiatek and Breen, the fair's director general Frank B. Davison came up with the concept for the designs. On December 7, 1922, Commission of Fine Arts chairman Charles Moore wrote to Buffalo nickel designer and sculptor member of the commission James Earle Fraser, "The Los Angeles people are planning to celebrate the Monroe Doctrine Centennial. They are going to have a 50-cent piece and have decided that on the obverse shall be the heads of President Monroe and John Quincy Adams ... On the reverse will be the western continents from Hudson Bay to Cape Horn with some dots for the West Indies and some indication of the Panama Canal ... It strikes me that the designs having been settled upon, the lastermodels could be worked out quite readily and that a pretty swell thing could be made."

Fraser contacted fellow New York sculptor Chester Beach

Chester A. Beach (May 23, 1881 – August 6, 1956) was an American sculptor who was known for his busts and medallic art.

Early life

Beach was born in San Francisco, California. He studied initially at the California School of Mechanical Art ...

, who agreed to do the work. On December 27, Moore wrote to Davison, informing him of Beach's hiring, and that Fraser and Beach had decided to change the reverse. Moore quoted Beach's description of the revised design:

Moore informed Davison that the commission had concurred with the revision, and that Beach had been instructed to complete work as quickly as possible so as to have the coins available at an early date. On February 24, 1923, commission secretary Hans Caemmerer showed the completed models to Assistant Director of the Mint Mary Margaret O'Reilly

Mary Margaret O'Reilly (October 14, 1865 – December 6, 1949) was an American civil servant who served as the assistant director of the United States Bureau of the Mint from 1924 until 1938. One of the United States government's highest- ...

, who was pleased with them. O'Reilly suggested that if Beach was certain there would be no further changes, that he send photographs of the models to the commission's offices, to be forwarded with its endorsement to the Bureau of the Mint in Washington. This was done, and the designs were approved by both Mint Director Frank Edgar Scobey and Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon

Andrew William Mellon (; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937), sometimes A. W. Mellon, was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, and politician. From the wealthy Mellon family of Pittsburgh, Pennsylv ...

on March 8. Moore was enthusiastic about the designs, writing to Davison on March 21 that "I feel great exultation over the way the model ... has turned out ... I do not know of a memorial ommemorativecoin which for sheer beauty equals this ..."

Design

William E. Pike, in his 2003 article in ''The Numismatist

''The Numismatist'' (formerly ''Numismatist'') is the monthly publication of the American Numismatic Association. ''The Numismatist'' contains articles written on such topics as coins, tokens, medals, paper money, and stock certificates. All mem ...

'' about the coin, deems the design "uninspired" and complains that the low relief of the coin leaves it without sufficient detail. Coin dealer and numismatic historian Q. David Bowers

Quentin David Bowers (born October 21, 1938) is an American numismatist, author, and columnist. Beginning in 1952, Bowers’s contributions to numismatics have continued uninterrupted and unabated to the present day.

states that because of the shallow relief, "newly minted coins had an insipid appearance. Few if any observers called them attractive." Art historian Cornelius Vermeule also complained about the relief, stating that it made the allegorical figures on the reverse "seem like mounted cut-outs ... the way the females are contoured to achieve their appearance of continents is a clever tour de force of calligraphic relief but an aesthetic monstrosity, a bad pun in art." He had no more praise for the obverse, "Adams, with his staring eye, is scarcely a portrait, and Monroe would not be recognized even by an expert."

The faint lines in the field around the continents represent various ocean currents, with the

The faint lines in the field around the continents represent various ocean currents, with the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream, together with its northern extension the North Atlantic Drift, is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the Unit ...

to the upper right of the reverse. Swiatek and Breen speculate that the reason ocean currents were shown was to symbolize the trade routes between the continents. They also consider the design to have an Art Deco

Art Deco, short for the French ''Arts Décoratifs'', and sometimes just called Deco, is a style of visual arts, architecture, and product design, that first appeared in France in the 1910s (just before World War I), and flourished in the Unit ...

look, though noting that the lettering has more of an older, Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (; ) is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. The style is known by different names in different languages: in German, in Italian, in Catalan, and also known as the Modern ...

appearance. Beach's monogram

A monogram is a motif made by overlapping or combining two or more letters or other graphemes to form one symbol. Monograms are often made by combining the initials of an individual or a company, used as recognizable symbols or logos. A series ...

, CB made into a circle, is found at lower right of the reverse.

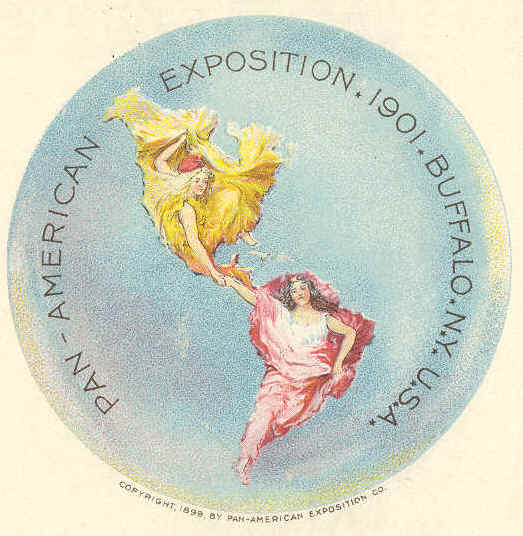

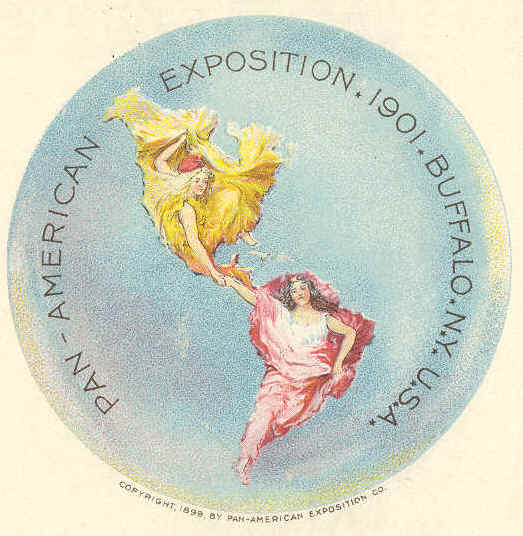

On July 23, 1923, Raphael Beck, who had designed the seal for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition

The Pan-American Exposition was a World's Fair held in Buffalo, New York, United States, from May 1 through November 2, 1901. The fair occupied of land on the western edge of what is now Delaware Park, extending from Delaware Avenue to Elmwood ...

, wrote to Mint Director Scobey to complain that the reverse design resembled his seal, which he had copyrighted in 1899, and that Beach should be given no further credit for it. The letter was forwarded to the Commission of Fine Arts for comment. In October, Fraser wrote to Beck, stating that he had suggested to Beach that he use figures to represent the continents instead of maps, and that he had never seen the Pan-American seal until Scobey forwarded the letter. According to Bowers, "A comparison of the 1901 and 1923 designs, however, shows that this was highly unlikely."

Distribution and collecting

In May and June 1923, 274,077 of the new half dollars were struck at theSan Francisco Mint

The San Francisco Mint is a branch of the United States Mint. Opened in 1854 to serve the gold mines of the California Gold Rush, in twenty years its operations exceeded the capacity of the first building. It moved into a new one in 1874, now kno ...

. Most of these were sent to the Los Angeles Clearing House, though 77 pieces were set aside for transmission to Philadelphia and examination by the 1924 United States Assay Commission

The United States Assay Commission was an agency of the United States government from 1792 to 1980. Its function was to supervise the annual testing of the gold, silver, and (in its final years) base metal coins produced by the United States Mint ...

.

The American Historical Revue and Motion Picture Industry Exposition was open from July 2 to August 4, 1923. The fair was located off of Figueroa Street in Exposition Park, just to the east of the brand-new

The American Historical Revue and Motion Picture Industry Exposition was open from July 2 to August 4, 1923. The fair was located off of Figueroa Street in Exposition Park, just to the east of the brand-new Los Angeles Coliseum

The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (also known as the L.A. Coliseum) is a multi-purpose stadium in the Exposition Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. Conceived as a hallmark of civic pride, the Coliseum was commissioned in 1921 as a me ...

, where every evening a complimentary show for exposition visitors, "Montezuma and the Fall of the Aztecs", was given. Admission to the fair was fifty cents, though fairgoers could purchase a coin for a dollar at the box office and enter without further charge. After the first week, organizers realized the public was not interested in the historical theme, but was there to see favorite movie stars. Exhibitors accordingly greatly expanded the space devoted to movie attractions, but the exposition was a financial failure. Those in charge of the fair had hoped to attract a million visitors; the actual attendance was about 300,000, many of whom were teenagers given complimentary admission in the final two weeks of the fair. With the fair flirting with insolvency throughout its run, officials hoped the planned visit of President Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

on August 6 would increase gate receipts, but Harding fell ill in San Francisco and died on August 2. According to Pike in his article, "its effect on the industry ashard to measure. However, if Hollywood owes its current status in any way to the event, then it was quite a success indeed."

Approximately 27,000 half dollars were sold at the price of $1, by mail, at banks, and at the fair. Sales continued after it closed, but by October 1923, they had dropped off to almost nothing, and the banks holding them released the remaining nine-tenths of the mintage into circulation, which accounts for the wear on most surviving specimens. Of those set aside, thousands more were spent during the Depression. The 2015 edition of ''A Guide Book of United States Coins

''A Guide Book of United States Coins (The Official Red Book)'', first compiled by R. S. Yeoman in 1946, is a price guide for coin collectors of coins of the United States dollar, commonly known as the Red Book.

Along with its sister publicatio ...

'' lists it at $75 in uncirculated MS-60. Swiatek, in his 2012 volume on commemoratives, notes that many specimens have been treated to make them appear brighter or less worn; these, like other circulated pieces, are worth less. An exceptional specimen, certified in MS-67 condition, sold at auction for $29,900 in 2009.

See also

* Early United States commemorative coinsNotes

References and bibliography

Books * * * * * * * Other sources * * * * * *External links

* {{Portal bar, California, Numismatics, United States Currencies introduced in 1923 Early United States commemorative coins Fifty-cent coins Cultural depictions of James Monroe Cultural depictions of John Quincy Adams United States silver coins Maps on coins 1923 in California Centennial half dollar Plagiarism controversies