The

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

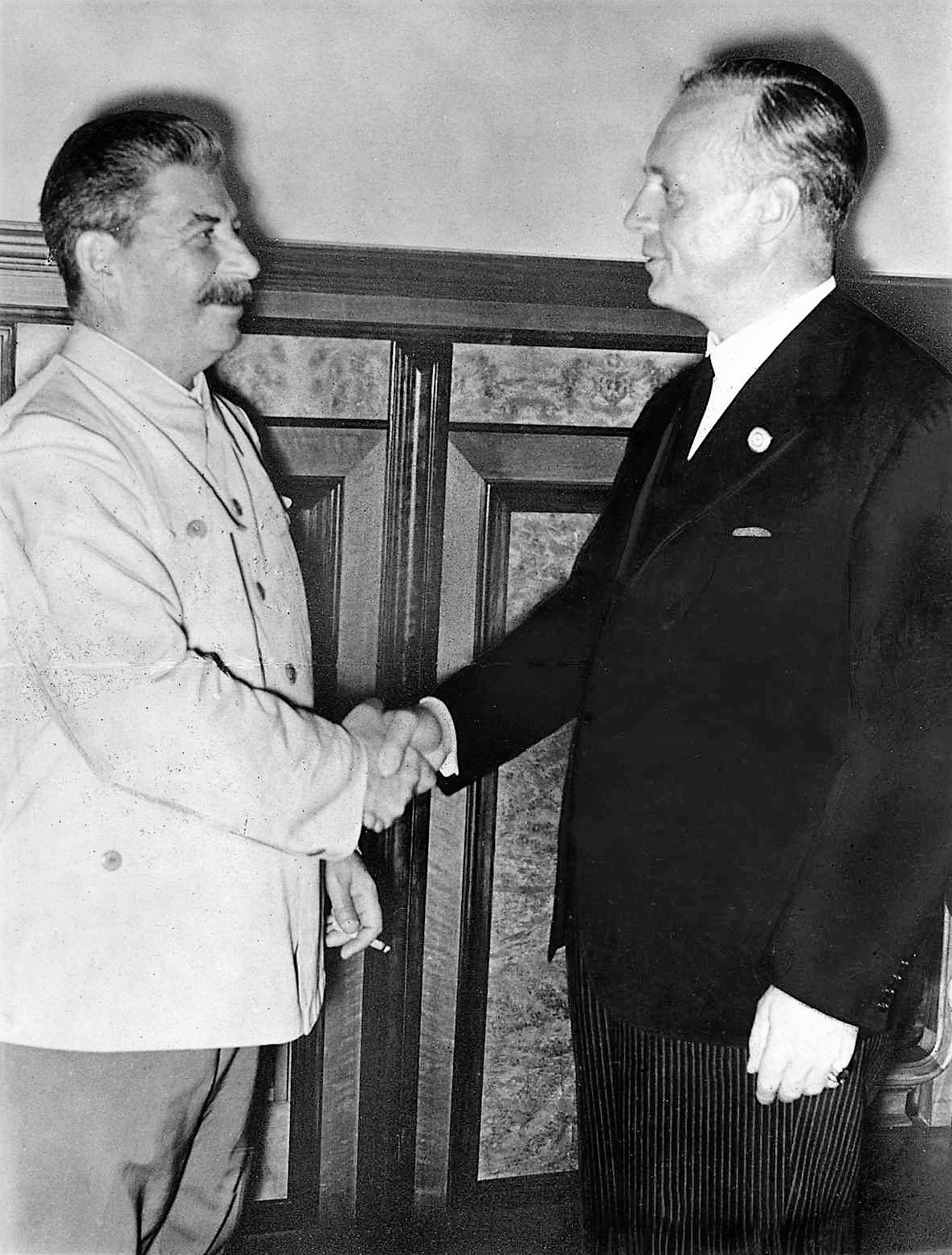

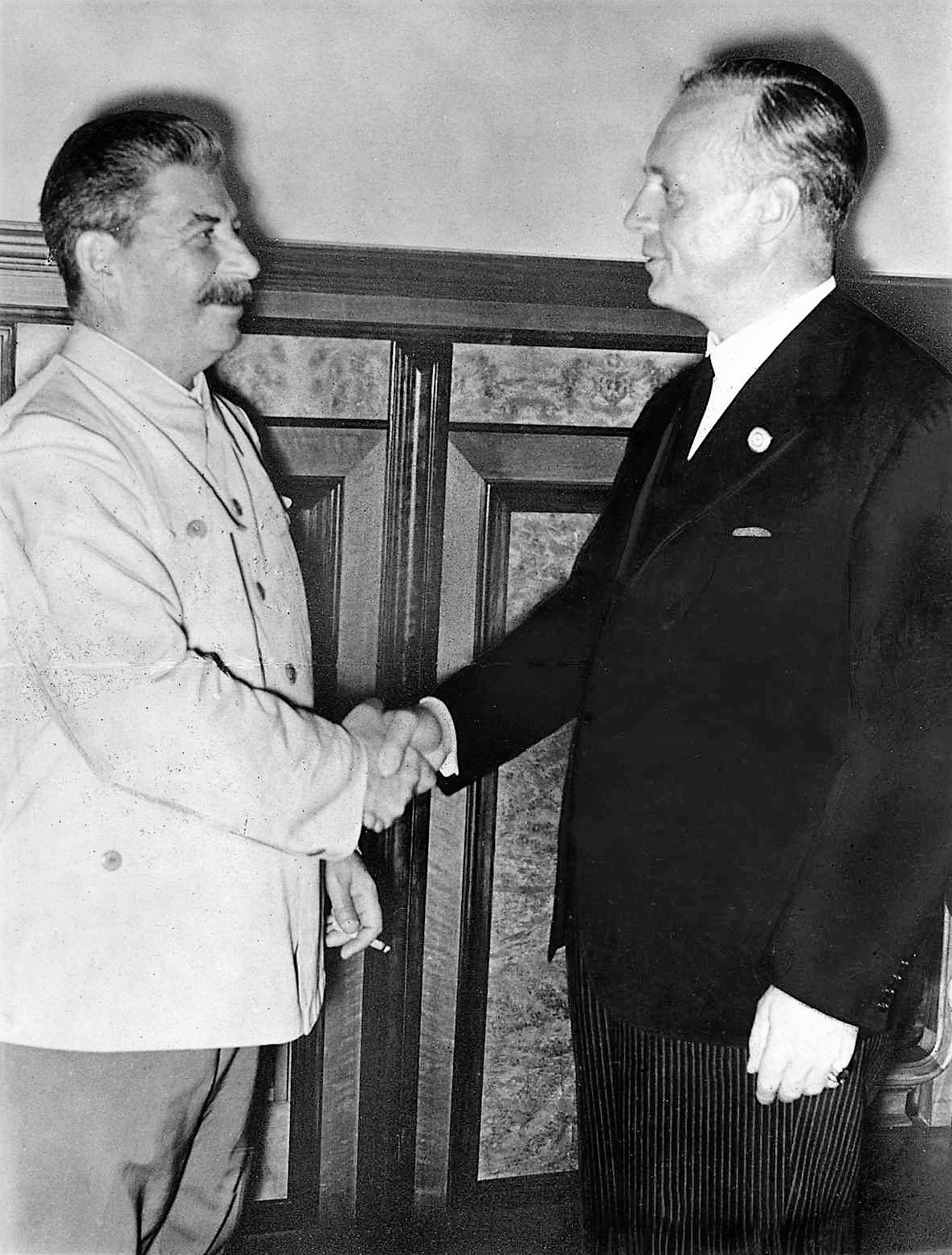

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

was an August 23, 1939, agreement between the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

colloquially named after Soviet foreign minister

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

and German foreign minister

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

. The treaty renounced warfare between the two countries. In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol dividing several eastern European countries between the parties.

Before the treaty's signing, the Soviet Union conducted negotiations with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

regarding a potential "Tripartite" alliance. Long-running talks between the Soviet Union and Germany over a potential economic pact expanded to include the military and political discussions, culminating in the pact, along with a

commercial agreement signed four days earlier.

Background

After World War I

After the

Russian Revolution of 1917,

Bolshevist Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

ended its fight against the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, including

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

by signing the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

.

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

''Soviet Foreign Policy 1917-1941'', Kreiger Publishing Company, 1960. Therein, Russia agreed to cede sovereignty and influence over parts of several

eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

an countries. Most of those countries became ostensible democratic republics following Germany's defeat and

signing of an armistice in the autumn of 1918. With the exception of

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

and

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, those countries also became independent. However, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk lasted only eight and a half months, when Germany renounced it and broke off diplomatic relations with Russia.

Before World War I, Germany and Russia had long shared a trading relationship.

Germany is a relatively small country with few natural resources. It lacks natural supplies of several key

raw materials

A raw material, also known as a feedstock, unprocessed material, or primary commodity, is a basic material that is used to produce goods, finished goods, energy, or intermediate materials that are feedstock for future finished products. As feedst ...

needed for economic and military operations.

Since the late 19th century, it had relied heavily upon Russian imports of raw materials.

Germany imported 1.5 billion Rechsmarks of raw materials and other goods annually from Russia before the war.

In 1922, the countries signed the

Treaty of Rapallo Following World War I there were two Treaties of Rapallo, both named after Rapallo, a resort on the Ligurian coast of Italy:

* Treaty of Rapallo, 1920, an agreement between Italy and the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the later Yugoslav ...

, renouncing territorial and financial claims against each other. The countries pledged neutrality in the event of an attack against one another with the

1926 Treaty of Berlin. While imports of Soviet goods to Germany fell after World War I, after trade agreements signed between the two countries in the mid-1920s, trade had increased to 433 million Reichsmarks per year by 1927.

In the early 1930s, this relationship fell as the more isolationist

Stalinist

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory o ...

regime asserted power and the abandonment of post-World War I military control decreased Germany's reliance on Soviet imports,

such that Soviet imports fell to 223 million Reichsmarks in 1934.

Mid-1930s

In the mid-1930s, the Soviet Union made repeated efforts to reestablish closer contacts with Germany.

The Soviet Union chiefly sought to repay debts from earlier trade with raw materials, while Germany sought to rearm, and the countries signed a credit agreement in 1935.

The

rise to power of the

Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

increased tensions between Germany, the Soviet Union and other countries with ethnic

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

, which were considered "

untermensch

''Untermensch'' (, ; plural: ''Untermenschen'') is a Nazi term for non- Aryan "inferior people" who were often referred to as "the masses from the East", that is Jews, Roma, and Slavs (mainly ethnic Poles, Serbs, and later also Russians). The ...

en" according to

Nazi racial ideology

The Nazi Party adopted and developed several pseudoscientific racial classifications as part of its ideology (Nazism) in order to justify the genocide of groups of people which it deemed racially inferior. The Nazis considered the putative "A ...

. The Nazis were convinced that ethnic Slavs were incapable of forming their own state and, accordingly, must be ruled by others.

[Wette, Wolfram, Deborah Lucas Schneider''The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality'', Harvard University Press, 2006 , page 15] Moreover, the

anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

Nazis associated ethnic Jews with both

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and international

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

,

both of which they opposed. Consequently, Nazis believed that Soviet untermenschen Slavs were being ruled by "''

Jewish Bolshevik

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, which alleges that the Jews were the originators of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and that they held primary power among the Bolsheviks who led the revo ...

''" masters. Two primary goals of Nazism were to eliminate Jews and seek

Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

("living space") for ethnic

Aryans to the east.

In 1934, Hitler spoke of an inescapable battle against "pan-Slav ideals", the victory in which would lead to "permanent mastery of the world", though he stated that they would "walk part of the road with the Russians, if that will help us."

Despite the political rhetoric, in 1936, the Soviets attempted to seek closer political ties to Germany along with an additional credit agreement, while Hitler rebuffed the advances, not wanting to seek closer political ties,

even though a 1936 raw material crisis prompted Hitler to decree a

Four Year Plan

The Four Year Plan was a series of economic measures initiated by Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany in 1936. Hitler placed Hermann Göring in charge of these measures, making him a Reich Plenipotentiary (Reichsbevollmächtigter) whose jurisdiction cut a ...

for rearmament "without regard to costs." In the 1930s, thanks to two

Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

cipher clerks, namely

Ernest Holloway Oldham

Ernest Holloway Oldham (September 10, 1894 – September 29, 1933) was a British traitor, employed as a cipher clerk in the British Foreign Office. He spied for the Soviet Union between 1929 and his death in 1933, in return for money. His job ...

and

John Herbert King

John Herbert King, alias 'MAG', was a British Foreign Office cypher clerk who provided Foreign Office communications to the Soviet Union between 1935 and 1937. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison as a spy in October 1939.

King was recruited b ...

, who sold the British diplomatic codes to the NKVD, the Soviets were able to read British diplomatic traffic. At the same time, the Soviet code-breakers were completely unable to break the German codes encrypted by the Enigma machine.

The fact that Soviet intelligence-gathering activities in Germany were performed through the underground German Communist Party, which was full of Gestapo informers, rendered most Soviet espionage in Germany ineffective. Stalin's decision to execute or imprison most of the German Communist emigres living in the Soviet Union during the

Great Terror finished off almost all Soviet espionage in the ''Reich''.

Tensions grew further after Germany and

Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

supported the

Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Spanish Nationalists in the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

in 1936, while the Soviets supported the partially socialist-led

Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

opposition. In November 1936, Soviet-German relations sank further when Germany and Japan entered the

Anti-Comintern Pact, which was purportedly directed against the

Communist International, though it contained a secret agreement that either side would remain neutral if the other became involved with the Soviet Union.

[Gerhard Weinberg: ''The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe 1933-36'', Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970, pages 346.] In November 1937,

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

also joined the Anti-Comintern Pact.

Late 1930s

The

Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against "Trotskyists" and members of "Right Opposition" of the Communist Party of th ...

of the mid-1930s seriously undermined Soviet prestige in the West. Soviet

purges

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

in 1937 and 1938 made a deal less likely by disrupting the already confused Soviet administrative structure necessary for negotiations and giving Hitler the belief that the Soviets' were militarily weak.

The Soviets were not invited to the Munich Conference regarding

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. The

Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

that followed marked the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1938 through a partial

German annexation, part of an

appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governm ...

of Germany.

After German needs for military supplies after the Munich Agreement and Soviet demand for military machinery increased, talks between the two countries occurred from late 1938 to March 1939.

The Soviet Third Five Year Plan would require massive new infusions of technology and industrial equipment.

An

autarkic

Autarky is the characteristic of self-sufficiency, usually applied to societies, communities, states, and their economic systems.

Autarky as an ideal or method has been embraced by a wide range of political ideologies and movements, especiall ...

economic approach or an alliance with England were impossible for Germany, such that closer relations with the Soviet Union were necessary, if not just for economic reasons alone.

At that time, Germany could supply only 25 percent of its

petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

needs, and without its primary

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

petroleum source in a war, would have to look to

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

.

Germany suffered the same natural shortfall and supply problems for

rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, and ...

and metal ores needed for hardened

steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

in war equipment ,

for which Germany relied on Soviet supplies or transit using Soviet rail lines.

Finally, Germany also imported 40 per cent of its fat and oil food requirements, which would grow if Germany conquered nations that were also net food importers,

and, thus, needed Soviet imports of Ukrainian grains or Soviet transshipments of

Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

n soybeans.

Moreover, an anticipated British blockade in the event of war and a cutoff of petroleum from the United States would create massive shortages for Germany regarding a number of key raw materials

Following Hitler's March 1939 denunciation of the 1934

German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact,

[Manipulating the Ether: The Power of Broadcast Radio in Thirties America]

Robert J. Brown Britain and France had made statements guaranteeing the sovereignty of Poland, and on April 25, signed a

Common Defense Pact with Poland, when that country refused to be associated with a four-power guarantee involving the USSR.

Initial talks

Potential for Soviet-German talk expansion

Germany and the Soviet Union discussed entering into an economic deal throughout early 1939.

For months, Germany had secretly hinted to Soviet diplomats that it could offer better terms for a political agreement than could Britain and France.

[Tentative Efforts To Improve German–Soviet Relations, April 17 – August 14, 1939]

/ref>["Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War 1917–1991" by Robert C. Grogin 2001, Lexington Books page 28] On March 10, Hitler in his official speech proclaimed that directly.[Zachary Shore. ''What Hitler Knew: The Battle for Information in Nazi Foreign Policy.'' Published by Oxford University Press US, 2005 , , p. 109] That same day, Stalin, in a speech to the Eighteenth Congress of the All-Union Communist Party, characterized western actions regarding Hitler as moving away from "collective security" and toward "nonintervention," with the goal being to direct Fascist aggression anywhere but against themselves.[Karski, J. The Great Powers and Poland, University Press, 1985, p.342] After the Congress concluded, the Soviet press mounted an attack on both France and Great Britain.NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

tended to provide Stalin with intelligence that fitted his preconceptions, thus reinforcing what he already believed.Rudolf von Scheliha

Rudolf "Dolf" von Scheliha (31 May 1897 – 22 December 1942) was a German aristocrat, cavalry officer and diplomat who became a resistance fighter and anti-Nazi who was linked to the Red Orchestra. Von Scheliha fought in the World War I and thi ...

, the First Secretary at the German embassy in Warsaw had been working as a Soviet spy since 1937, keeping the Kremlin well informed about the state of German-Polish relations, and it was due to intelligence provided by him that the Soviets knew that Hitler was seriously considering invading Poland from March 1939 onward, giving the orders for an invasion of Poland in May. On 13 March 1939 Scheliha reported to Moscow that he had conversation with one of Ribbentrop's aides, a Peter Kleist, who told him Germany would probably attack Poland sometime that year. In his reports to Moscow, Scheliha made clear that the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' had attempted to reduce Poland down to a German satellite in the winter of 1938-39, and the Poles had refused to play that role. At the same time, the chief Soviet spy in Japan, Richard Sorge had reported to Moscow that the German attempt to convert the Anti-Comintern Pact into a military alliance had failed, as Germany wanted the alliance to be directed against Britain while Japan wanted the alliance to be directed against the Soviet Union. On 5 April 1939, Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker, the State Secretary at the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' ordered Count Hans-Adolf von Moltke, the German ambassador to Poland, that he was under no conditions to engage in talks with the Poles over resolving the dispute over the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (german: Freie Stadt Danzig; pl, Wolne Miasto Gdańsk; csb, Wòlny Gard Gduńsk) was a city-state under the protection of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gda ...

(modern Gdansk) as the Danzig issue was just a pretext for war, and he was afraid if talks did begin, the Poles might actually agree to Danzig rejoining Germany, thereby depriving the ''Reich'' of its pretext. Scheliha in his turn informed Moscow that the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' would not engage in talks for a diplomatic solution to the Danzig issue, indicating that German policy towards Poland was not a policy with a high risk of war, but was a policy aimed at causing a war.

On April 7, a Soviet diplomat visited the German Foreign Ministry stating that there was no point in continuing the German-Soviet ideological struggle and that the countries could conduct a concerted policy. Ten days later, the Soviet ambassador Alexei Merekalov met Ernst von Weizsäcker, the number two man at the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' and presented him a note requesting speedy removal of any obstacles for fulfillment of military contracts signed between Czechoslovakia and the USSR before the former was occupied by Germany.[ Roberts (1992; Historical Journal) p. 921-926] According to German accounts, at the end of the discussion, the ambassador stated "'there exists for Russia no reason why she should not live with us on a normal footing. And from normal the relations might become better and better."Herbert von Dirksen

Eduard Willy Kurt Herbert von Dirksen (2 April 1882 – 19 December 1955) was a German diplomat (and from 1936 when he joined the party, specifically a Nazi diplomat) who was the last German ambassador to Britain before World War II.

Early lif ...

judged the cables credible and passed them along in his reports to Berlin.

Tripartite talks begin

Starting in mid-March 1939, the Soviet Union, Britain and France traded a flurry of suggestions and counterplans regarding a potential political and military agreement.purges

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

, could not serve as a main military participant.

May changes

Litvinov dismissal

On May 3, Stalin replaced Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov with Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, which significantly increased Stalin's freedom to maneuver in foreign policy.Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, removed an obstacle to negotiations with Germany.[Israeli?, Viktor Levonovich, ''On the Battlefields of the Cold War: A Soviet Ambassador's Confession'', Penn State Press, 2003, , page 10][Osborn, Patrick R., ''Operation Pike: Britain Versus the Soviet Union, 1939-1941'', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, , page xix][Levin, Nora, ''The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival'', NYU Press, 1988, , page 330. Litvniov "was referred to by the German radio as 'Litvinov-Finkelstein'-- was dropped in favor of Vyascheslav Molotov. 'The emininent Jew', as Churchill put it, 'the target of German antagonism was flung aside . . . like a broken tool . . . The Jew Litvinov was gone and Hitler's dominant prejudice placated.'"][In an introduction to a 1992 paper, Geoffrey Roberts writes: "Perhaps the only thing that can be salvaged from the wreckage of the orthodox interpretation of Litvinov's dismissal is some notion that, by appointing Molotov foreign minister, Stalin was preparing for the contingency of a possible deal with Hitler. In view of Litvinov's Jewish heritage and his militant anti-nazism, that is not an unreasonable supposition. But it is a hypothesis for which there is as yet no evidence. Moreover, we shall see that what evidence there is suggests that Stalin's decision was determined by a quite different set of circumstances and calculations", Geoffrey Roberts. The Fall of Litvinov: A Revisionist View Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 639-657 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/260946] Stalin immediately directed Molotov to "purge the ministry of Jews."anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

coalition, association with the doctrine of collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, political, regional, or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and therefore commits to a collective response to threats t ...

with France and Britain, and pro-Western orientation by the standards of the Kremlin, his dismissal indicated the existence of a Soviet option of rapprochement with Germany.[ Montefiore 2005, p. 312]

May tripartite negotiations

Although informal consultations started in late April, the main negotiations between the Soviet Union, Britain and France began in May.Georges Bonnet

Georges-Étienne Bonnet (22/23 July 1889 – 18 June 1973) was a French politician who served as foreign minister in 1938 and 1939 and was a leading figure in the Radical Party.

Early life

Bonnet was born in Bassillac, Dordogne, the son of ...

told the Soviet Ambassador to France Jakob Suritz that he was willing to support turning over all of eastern Poland to the Soviet Union, regardless of Polish opposition, if that was the price of an alliance with Moscow.

German supply concerns and potential political discussions

In May, German war planners also became increasingly concerned that, without Russian supplies, Germany would need to find massive substitute quantities of 165,000 tons of manganese and almost 2 million tons of oil per year.

Baltic sticking point and German rapprochement

Mixed signals

The Soviets sent mixed signals thereafter.Mikoyan

Russian Aircraft Corporation "MiG" (russian: Российская самолётостроительная корпорация „МиГ“, Rossiyskaya samolyotostroitel'naya korporatsiya "MiG"), commonly known as Mikoyan and MiG, was a Russi ...

argued on June 2 to a German official that Moscow "had lost all interest in these conomicnegotiations' as a result of earlier German procrastination."

Tripartite talks progress and Baltic moves

On June 2, the Soviet Union insisted that any mutual assistance pact should be accompanied by a military agreement describing in detail the military assistance that the Soviets, French and British would provide.Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and Latvia signed non-aggression pacts with Germany, creating suspicions that Germany had ambitions in a region through which it could attack the Soviet Union.

British attempt to stop German armament

On June 8, the Soviets had agreed that a high ranking German official could come to Moscow to continue the economic negotiations, which occurred in Moscow on July 3.

Tripartite talks regarding "indirect aggression"

After weeks of political talks that began after the arrival of Central Department Foreign Office head William Strang

William Strang (13 February 1859 – 12 April 1921) was a Scottish painter and printmaker, notable for illustrating the works of Bunyan, Coleridge and Kipling.

Early life

Strang was born at Dumbarton, the son of Peter Strang, a builder, an ...

, on July 8, the British and French submitted a proposed agreement, to which Molotov added a supplementary letter. Talks in late July stalled over a provision in Molotov's supplementary letter stating that a political turn to Germany by the Baltic states constituted "indirect aggression",

Soviet-German political negotiation beginnings

On July 18, Soviet trade representative Yevgeniy Barbarin visited Julius Schnurre, saying that the Soviets would like to extend and intensify German-Soviet relations.

Addressing past hostilities

On August 3, German Foreign Minister Joachim Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

told Soviet diplomats that "there was no problem between the Baltic and the Black Sea that could not be solved between the two of us."anti-capitalism

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as s ...

, stating "there is one common element in the ideology of Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union: opposition to the capitalist democracies,"Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

and the Soviet renunciation of a world revolution.

Final negotiations

Finalizing the economic agreement

In August, as Germany scheduled its invasion of Poland on August 25 and prepared for war with France, German war planners estimated that, with an expected British naval blockade, if the Soviet Union became hostile, Germany would fall short of their war mobilization requirements of oil, manganese, rubber and foodstuffs by huge margins.

Tripartite military talks begin

The Soviets, British and French began military negotiations in August. They were delayed until August 12 because the British military delegation, which did not include Strang, took six days to make the trip traveling in a slow merchant ship, undermining the Soviets' confidence in British resolve.annex

Annex or Annexe refers to a building joined to or associated with a main building, providing additional space or accommodations.

It may also refer to:

Places

* The Annex, a neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada

* The Annex (New H ...

disputed territories, the Eastern Borderlands, received by Poland in 1920 after the Treaty of Riga ending the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

. The British and French contingent communicated the Soviet concern over Poland to their home offices and told the Soviet delegation that they could not answer this political matter without their governments' approval.

Delayed commercial agreement signing

After Soviet and German officials in Moscow first finalized the terms of a seven-year German-Soviet Commercial Agreement, German officials became nervous that the Soviets were delaying its signing on August 19 for political reasons.Tass

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

published a report that the Soviet-British-French talks had become snarled over the Far East and "entirely different matters", Germany took it as a signal that there was still time and hope to reach a Soviet-German deal.

Soviets adjourn tripartite military talks and strike a deal with Germany

After the Poles' resistance to pressure,

Pact signing

On August 24, a 10-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other." Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, according to which the states of

On August 24, a 10-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other." Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, according to which the states of Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

".[''Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact''](_blank)

executed August 23, 1939

Poland was to be partitioned in the event of its "political rearrangement".Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, primarily populated with Ukrainians and Belarusians, in case of its dissolution, and additionally Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

.Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, then part of Romania, was to be joined to the Moldovan ASSR, and become the Moldovan SSR under control of Moscow.

Events during the Pact's operation

Immediate dealings with Britain

The day after the Pact was signed, the French and British military negotiation delegation urgently requested a meeting with Voroshilov.

Division of eastern Europe

On September 1, 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of western Poland started World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

invaded eastern Poland and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

to the Soviet Union.[Wettig, Gerhard, ''Stalin and the Cold War in Europe'', Rowman & Littlefield, Landham, Md, 2008, , page 20]

After a Soviet attempt to invade Finland faced stiff resistance, the combatants signed an interim peace, granting the Soviets approximately 10 per cent of Finnish territory.[Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, ''Stalin's Cold War'', New York : Manchester University Press, 1995, ] The Soviet Union also sent troops into Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

.[Senn, Alfred Erich, ''Lithuania 1940: Revolution from Above'', Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ] Thereafter, governments in all three Baltic countries requesting admission to the Soviet Union were installed.[Wettig, Gerhard, ''Stalin and the Cold War in Europe'', Rowman & Littlefield, Landham, Md, 2008, , page 21]

Further dealings

Germany and the Soviet Union entered an intricate trade pact on February 11, 1940 that was over four times larger than the one the two countries had signed in August 1939,[Johari, J.C., ''Soviet Diplomacy 1925–41: 1925–27'', Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2000, pages 134-137]

Discussions in the fall and winter of 1940–41 ensued regarding the potential entry of the Soviet Union as the fourth members of the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

.[Brackman, Roman, ''The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life'', London and Portland, Frank Cass Publishers, 2001, , page 341] The countries never came to an agreement on the issue.

Aftermath

German invasion of the Soviet Union

Nazi Germany terminated the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with its invasion of the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

on June 22, 1941.

Post-war commentary regarding Pact negotiations

The reasons behind signing the pact

There is no consensus among historians regarding the reasons that prompted the Soviet Union to sign the pact with Nazi Germany. According to Ericson, the opinions "have ranged from seeing the Soviets as far-sighted anti-Nazis, to seeing them as reluctant appeasers, as cautious expansionists, or as active aggressors and blackmailers". Edward Hallett Carr

Edward Hallett Carr (28 June 1892 – 3 November 1982) was a British historian, diplomat, journalist and international relations theorist, and an opponent of empiricism within historiography. Carr was best known for ''A History of Soviet Russi ...

argued that it was necessary to enter into a non-aggression pact to buy time, since the Soviet Union was not in a position to fight a war in 1939, and needed at least three years to prepare. He stated: "In return for non-intervention Stalin secured a breathing space of immunity from German attack." According to Carr, the "bastion" created by means of the Pact, "was and could only be, a line of defense against potential German attack." An important advantage (projected by Carr) was that "if Soviet Russia had eventually to fight Hitler, the Western Powers would already be involved."

However, during the last decades, this view has been disputed. Historian Werner Maser stated that "the claim that the Soviet Union was at the time threatened by Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

, as Stalin supposed,...is a legend, to whose creators Stalin himself belonged." In Maser's view (1994: 42), "neither Germany nor Japan were in a situation finvading the USSR even with the least perspective icof success," and this could not have been unknown to Stalin.

The extent to which the Soviet Union's post-Pact territorial acquisitions may have contributed to preventing its fall (and thus a Nazi victory in the war) remains a factor in evaluating the Pact. Soviet sources point out that the German advance eventually stopped just a few kilometers away from Moscow, so the role of the extra territory might have been crucial in such a close call. Others postulate that Poland and the Baltic countries played the important role of buffer state

A buffer state is a country geographically lying between two rival or potentially hostile great powers. Its existence can sometimes be thought to prevent conflict between them. A buffer state is sometimes a mutually agreed upon area lying between t ...

s between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, and that the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a precondition not only for Germany's invasion of Western Europe, but also for the Third Reich's invasion of the Soviet Union. The military aspect of moving from established fortified positions on the Stalin Line into undefended Polish territory could also be seen as one of the causes of rapid disintegration of Soviet armed forces in the border area during the German 1941 campaign, as the newly constructed Molotov Line was unfinished and unable to provide Soviet troops with the necessary defense capabilities.

Historians have debated whether Stalin was planning an invasion of German territory in the summer of 1941. Most historians agreed that the geopolitical differences between the Soviet Union and the Axis made war inevitable, and that Stalin had made extensive preparations for war and exploited the military conflict in Europe to his advantage. A number of German historians have debunked the claim that Operation Barbarossa was a preemptive strike. Such as Andreas Hillgruber, Rolf-Dieter Müller

__NOTOC__

Rolf-Dieter Müller (born 9 December 1948) is a German military historian and political scientist, who has served as Scientific Director of the German Armed Forces Military History Research Office since 1999. Rolf-Dieter Müller, is also ...

, and Christian Hartmann, they also acknowledge the Soviets were aggressive to their neighbors

Recent studies, based on 70 years old archives, have found that before signing non-aggression pact with Germany, the Soviet Union proposed an anti-German alliance to Britain and France. The Soviets proposed sending more than a million Soviet troops to the German border in an effort to entice Britain and France into an anti-German alliance. But the British and French side did not respond to the Soviet offer, made on August 15, 1939. Instead, the Soviets turned to Germany, signing the non-aggression pact with Germany barely a week later.

Documentary evidence of early Soviet-German rapprochement

In 1948, the U.S. State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

published a collection of documents recovered from the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, that formed a documentary base for studies of Nazi-Soviet relations.[Geoffrey Roberts.''The Soviet Decision for a Pact with Nazi Germany''. Soviet Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1 (1992), pp. 57-78] This collection contains the German State Secretary's account on a meeting with Soviet ambassador Merekalov. This memorandum reproduces the following ambassador's statement: "'there exists for Russia no reason why she should not live with us on a normal footing. And from normal the relations might become better and better."

The next documentary evidence is the memorandum on the May 17 meeting between the Soviet ambassador and German Foreign Office official, where the ambassador "stated in detail that there were no conflicts in foreign policy between Germany and Soviet Russia and that therefore there was no reason for any enmity between the two countries."

The third document is the summary of the May 20 meeting between Molotov and German ambassador von der Schulenburg.[Memorandum by the German Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Schulenburg) May 20, 193]

/ref> According to the document, Molotov told the German ambassador that he no longer wanted to discuss only economic matters, and that it was necessary to establish a "political basis",

The last document is the German State Office memorandum on the telephone call made on June 17 by Bulgarian ambassador Draganov.

Litvinov's dismissal and Molotov's appointment

Many historians note that the dismissal of Foreign Minister Litvinov, whose Jewish ethnicity was viewed unfavorably by Nazi Germany, removed a major obstacle to negotiations between them and the USSR.

Carr, however, has argued that the Soviet Union's replacement of Litvinov with Molotov on May 3, 1939, indicated not an irrevocable shift towards alignment with Germany, but rather was Stalin's way of engaging in hard bargaining with the British and the French by appointing a tough negotiator, namely Molotov, to the Foreign Commissariat. Albert Resis

Albert Resis (December 16, 1921 – March 10, 2021) was an American academic and writer in the field of Russian history. He worked as a professor of history at Northern Illinois University from 1964 to 1992, and then as a Professor emeritus from 19 ...

argued that the replacement of Litvinov by Molotov was both a warning to Britain and a signal to Germany. Derek Watson argued that Molotov could get the best deal with Britain and France because he was not encumbered with the baggage of collective security and could more easily negotiate with Germany. Geoffrey Roberts argued that Litvinov's dismissal helped the Soviets with British-French talks, because Litvinov doubted or maybe even opposed such discussions.[Geoffrey Roberts. The Fall of Litvinov: A Revisionist View. ''Journal of Contemporary History'' Vol. 27, No. 4 (Oct., 1992), pp. 639-657. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/260946. "''the foreign policy factor in Litvinov's downfall was the desire of Stalin and Molotov to take charge of foreign relations in order to pursue their policy of a triple alliance with Britain and France - a policy whose utility Litvinov doubted and may even have opposed or obstructed.''"]

See also

* Timeline of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

Notes

References

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

1939 in the Soviet Union

1939 in Germany

Treaties of the Soviet Union

Eastern European theatre of World War II

Romania in World War II

Germany–Soviet Union relations

Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

Military history of Germany during World War II

1939 in international relations

Treaties of Nazi Germany

Negotiations

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more people or parties to reach the desired outcome regarding one or more issues of conflict. It is an interaction between entities who aspire to agree on matters of mutual interest. The agreement ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact negotiations

On August 24, a 10-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other." Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, according to which the states of

On August 24, a 10-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included: consultation; arbitration if either party disagreed; neutrality if either went to war against a third power; no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other." Most notably, there was also a secret protocol to the pact, according to which the states of