Modern history of Ukraine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Overview of the History of Ukraine

''. Part I. In 1846, in Moscow the " Istoriya Rusov ili Maloi Rossii" (History of Ruthenians or Little Russia) was published. During the

, ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Quote: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33 – a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself." In 1941, the Soviet Union was invaded by Germany and its other allies. Many Ukrainians initially regarded the

Following the 17th century failed attempt to regain statehood in the form of the

Following the 17th century failed attempt to regain statehood in the form of the

The Ukrainian national idea lived on during the inter-war years and was even spread to a large territory with the traditionally mixed population in the east and south that became part of the Ukrainian Soviet republic. The

The Ukrainian national idea lived on during the inter-war years and was even spread to a large territory with the traditionally mixed population in the east and south that became part of the Ukrainian Soviet republic. The  The change in the Soviet economic policies towards the fast-pace

The change in the Soviet economic policies towards the fast-pace

The

The

Ukraine

article, page 51. The purged Ukrainian political leadership was largely replaced by the cadre sent from

Following the end of World War I, the eastern part of the former Austrian province of

Following the end of World War I, the eastern part of the former Austrian province of

Following the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland, including

Following the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland, including  The Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population's possible dissatisfaction with Soviet political and economic policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, and deported many Ukrainians to forced labour in Germany. In their active resistance to Nazi Germany, the Ukrainians comprised a significant share of the Red Army and its leadership as well as the underground and resistance movements.

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at seven million, including over a million Jews shot and killed by the ''

The Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population's possible dissatisfaction with Soviet political and economic policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, and deported many Ukrainians to forced labour in Germany. In their active resistance to Nazi Germany, the Ukrainians comprised a significant share of the Red Army and its leadership as well as the underground and resistance movements.

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at seven million, including over a million Jews shot and killed by the '' Many civilians fell victim to atrocities, forced labor, and even massacres of whole villages in reprisal for attacks against Nazi forces. Of the estimated eleven million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis, about 16% (1.7 million) were ethnic Ukrainians. Moreover, Ukraine saw some of the biggest battles of the war starting with the encirclement of Kyiv (the city itself fell to the Germans on 19 September 1941 and was later acclaimed as a ''

Many civilians fell victim to atrocities, forced labor, and even massacres of whole villages in reprisal for attacks against Nazi forces. Of the estimated eleven million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis, about 16% (1.7 million) were ethnic Ukrainians. Moreover, Ukraine saw some of the biggest battles of the war starting with the encirclement of Kyiv (the city itself fell to the Germans on 19 September 1941 and was later acclaimed as a ''

A fascist hero in democratic Kiev

. New York Review of Books. February 24, 2010J. P. Himka

Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history

University of Alberta. 28 March 2011. p. 4 Late October 1944 the last territory of current Ukraine (near

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

emerged as the concept of a nation, and the Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Ort ...

as a nationality, with the Ukrainian National Revival which began in the late 18th and early 19th century. The first wave of national revival is traditionally connected with the publication of the first part of "Eneyida" by Ivan Kotlyarevsky

Ivan Petrovych Kotliarevsky ( uk, Іван Петрович Котляревський) ( in Poltava – in Poltava, Russian Empire, now Ukraine) was a Ukrainian writer, poet and playwright, social activist, regarded as the pioneer of modern Ukr ...

(1798).Yaroslav Hrytsak

Yaroslav Hrytsak ( ua, Ярослав Грицак; born 1 January 1960) is a Ukrainian historian, Doctor of Historical Sciences and professor of the Ukrainian Catholic University. Director of the Institute for Historical Studies of Ivan Franko ...

. Overview of the History of Ukraine

''. Part I. In 1846, in Moscow the " Istoriya Rusov ili Maloi Rossii" (History of Ruthenians or Little Russia) was published. During the

Spring of Nations

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

, in 1848 in Lemberg (Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

) the Supreme Ruthenian Council

Supreme Ruthenian Council ( uk, Головна Руська Рада, Holovna Ruska Rada) was the first legal Ruthenian political organization that existed from May 1848 to June 1851.

It was founded on 2 May 1848 in Lemberg (today Lviv), Austri ...

was created which declared that Galician Ruthenians were part of the bigger Ukrainian nation. The council adopted the yellow and blue flag, the current Ukrainian flag

The flag of Ukraine ( uk, Прапор України, Prapor Ukrainy) consists of equally sized horizontal bands of blue and yellow.

The blue and yellow bicolour first appeared during the 1848 Spring of Nations in Lemberg, then part of the ...

.

Ukraine first declared its independence with the invasion of Bolsheviks in late 1917. Following the conclusion of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and with the Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet Wa ...

, Ukraine was partitioned once again between Poland and the Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. The Bolshevik-occupied portion of the territory became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, with some boundary adjustments.

In 1922, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, together with the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

and the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

, conventional_long_name = Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

, common_name = Transcaucasian SFSR

, p1 = Armenian Soviet Socialist RepublicArmenian SSR

, flag_p1 = Flag of SSRA ...

, became the founding members of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. The Soviet famine of 1932–33

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

or Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

killed an estimated 6 to 8 million people in the Soviet Union, the majority of them in Ukraine.famine of 1932–33", ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Quote: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33 – a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself." In 1941, the Soviet Union was invaded by Germany and its other allies. Many Ukrainians initially regarded the

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

soldiers as liberators from Soviet rule, while others formed an anti-German partisan movement. Some elements of the Ukrainian nationalist underground formed a Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army ( uk, Українська повстанська армія, УПА, translit=Ukrayins'ka povstans'ka armiia, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and later partisan formation. During World ...

that fought both Soviet and Nazi forces. In 1945, Ukraine was made one of the founding members of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

even though it was part of the Soviet Union. In 1954 the Crimean Oblast

During the existence of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, different governments existed within the Crimean Peninsula. From 1921 to 1936, the government in the Crimean Peninsula was known as the Crimean Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic; ...

was transferred from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

at the end of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, Ukraine became an independent state, formalized with a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

. With the enlargement of the European Union

The European Union (EU) has expanded a number of times throughout its history by way of the accession of new member states to the Union. To join the EU, a state needs to fulfil economic and political conditions called the Copenhagen criteria ...

in 2004, Ukraine became an area of overlapping spheres of influence between the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

and the Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

. This manifested in a political division between the "pro-European" Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austr ...

and the "pro-Russian" Eastern Ukraine

Eastern Ukraine or east Ukraine ( uk, Східна Україна, Skhidna Ukrayina; russian: Восточная Украина, Vostochnaya Ukraina) is primarily the territory of Ukraine east of the Dnipro (or Dnieper) river, particularly Khar ...

, which led to an ongoing series of political turmoil, including the Orange Revolution

The Orange Revolution ( uk, Помаранчева революція, translit=Pomarancheva revoliutsiia) was a series of protests and political events that took place in Ukraine from late November 2004 to January 2005, in the immediate afterm ...

, the Euromaidan

Euromaidan (; uk, Євромайдан, translit=Yevromaidan, lit=Euro Square, ), or the Maidan Uprising, was a wave of demonstrations and civil unrest in Ukraine, which began on 21 November 2013 with large protests in Maidan Nezalezhno ...

protests, and the Russian invasion.

The 19th century

Following the 17th century failed attempt to regain statehood in the form of the

Following the 17th century failed attempt to regain statehood in the form of the Cossack Hetmanate

The Cossack Hetmanate ( uk, Гетьманщина, Hetmanshchyna; or ''Cossack state''), officially the Zaporizhian Host or Army of Zaporizhia ( uk, Військо Запорозьке, Viisko Zaporozke, links=no; la, Exercitus Zaporoviensis) ...

, the future Ukrainian territory again ended up divided between three empires: the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

.

In the second half of the 18th century, Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

instigated hysteria in the local Eastern Orthodox population by promising protection from Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and support leading to an armed conflict Koliivshchyna

The Koliivshchyna ( uk, Коліївщина, pl, koliszczyzna) was a major haidamaky rebellion that broke out in Right-bank Ukraine in June 1768, caused by money (Dutch ducats coined in Saint Petersburg) sent by Russia to Ukraine to pay for th ...

in the neighboring right-bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine ( uk , Правобережна Україна, ''Pravoberezhna Ukrayina''; russian: Правобережная Украина, ''Pravoberezhnaya Ukraina''; pl, Prawobrzeżna Ukraina, sk, Pravobrežná Ukrajina, hu, Jobb p ...

which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

and resulting in the Polish Bar Confederation

The Bar Confederation ( pl, Konfederacja barska; 1768–1772) was an association of Polish nobles ( szlachta) formed at the fortress of Bar in Podolia (now part of Ukraine) in 1768 to defend the internal and external independence of the Polis ...

, Russian military invasion of Poland and its internal affairs, and successful partitions of the last. By the end of the 18th century, most of Ukraine was completely annexed by Russia. At the same time the Russian Empire gradually gained control over the area of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

coast (northern Pontic coast) which was part of the Ottoman realm at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish Wars

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

of 1735–39, 1768–74, 1787–92.

The lands were generously given to the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

, and the unfree peasantry were transferred to cultivate the Pontic steppe. Forcing the local Nogai population out and resettling the Crimean Greeks, Catherine the Great renamed all populated places and invited other European settlers to these newly conquered lands: Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

, Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

(Black Sea Germans

The Black Sea Germans (german: Schwarzmeerdeutsche; russian: черноморские немцы; uk, чорноморські німці) are ethnic Germans who left their homelands (starting in the late-18th century, but mainly in the e ...

, Crimea Germans

The Crimea Germans (german: Krimdeutsche) were ethnic German settlers who were invited to settle in the Crimea as part of the East Colonization.

History

From 1783 onwards, there was a systematic settlement of Russians, Ukrainians, and Germans to ...

, Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (german: Wolgadeutsche, ), russian: поволжские немцы, povolzhskiye nemtsy) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov a ...

), Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

*Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

*Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

* Swiss Internation ...

, and others. Some Estonian Swedes were deported to southern Ukraine. Since then there exists the old Swedish village of Gammalsvenskby

Gammalsvenskby ( sv, Gammölsvänskbi, label=Gammalsvenska, lit=Old Swedish Village; uk, Старошведське, translit=Staroshvedske; german: Alt-Schwedendorf) is a former village that is now a neighbourhood of Zmiivka ( uk, Зміїв ...

–Zmiivka.

Ukrainian writers and intellectuals were inspired by the nationalistic spirit stirring other European peoples existing under other imperial governments. Russia, fearing separatism, imposed strict limits on attempts to elevate the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state lan ...

and culture, even banning its use and study. The Russophile

Russophilia (literally love of Russia or Russians) is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture. The antonym is Russophobia. In the 19th Cen ...

policies of Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cult ...

and Panslavism led to an exodus of a number some Ukrainian intellectuals into Western Ukraine, while others embraced a Pan-Slavic or Russian identity, with many Russian authors or composers of the 19th century being of Ukrainian origin (notably Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

).

In the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

most of the elite that ruled Galicia were of Austrian or Polish descent, with the Ruthenians

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sou ...

mostly representing the peasantry. During the 19th century, Russophilia

Russophilia (literally love of Russia or Russians) is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture. The antonym is Russophobia. In the 19th Century, ...

was a common occurrence among the Slavic population, but the mass exodus of Ukrainian intellectuals escaping from Russian repression in Eastern Ukraine, as well as the intervention of Austrian authorities, caused the movement to be replaced by Ukrainophilia

Ukrainophilia is the love of or identification with Ukraine and Ukrainians; its opposite is Ukrainophobia. The term is used primarily in a political and cultural context. "Ukrainophilia" and "Ukrainophile" are the terms used to denote pro-Ukrai ...

, which would then cross-over into the Russian Empire.

First World War, the revolutions and aftermath

When World War I and series of revolutions across Europe, including theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

in Russia, shattered many existing empires such as the Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

and Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

ones, people of Ukraine were caught in the middle. Between 1917 and 1919, several separate Ukrainian republics manifested independence, the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

, the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, the Ukrainian State

The Ukrainian State ( uk, Українська Держава, translit=Ukrainska Derzhava), sometimes also called the Second Hetmanate ( uk, Другий Гетьманат, translit=Druhyi Hetmanat, link=no), was an anti-Bolshevik government ...

, the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

, and numerous Bolshevik revkoms.

As the area of Ukraine fell into warfare and anarchy, it was also fought over by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Austrian forces, the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

of Bolshevik Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, the White Forces of General Denikin, the Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 62,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military history stre ...

, anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

s led by Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

. Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

itself was occupied by many different armies. The city was captured by the Bolsheviks on 9 February 1918, by the Germans on 2 March 1918, by the Bolsheviks a second time on 5 February 1919, by the White Army on 31 August 1919, by Bolsheviks for a third time on 15 December 1919, by the Polish Army on 6

May 1920, and finally by the Bolsheviks for the fourth time on 12 June 1920.

The defeat in the Polish-Ukrainian War and then the failure of the Piłsudski's and Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian People' ...

's '' Warsaw agreement of 1920'' to oust the Bolsheviks during the 1920 Kiev Offensive led almost to the occupation of Poland itself. This led to the Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

, which culminated in the signing of the Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet Wa ...

in March 1921. The Peace of Riga divided the disputed territories between Poland and Soviet Russia. Specifically, the part of Ukraine west of the Zbruch

The Zbruch ( uk, Збруч, pl, Zbrucz) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.Збруч< ...

river was incorporated into Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, while the eastern portion became part of the Soviet Union as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

. The first capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest city and municipality in Ukraine.

; in 1934, the capital was relocated to Kyiv.

Interbellum

Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian national idea lived on during the inter-war years and was even spread to a large territory with the traditionally mixed population in the east and south that became part of the Ukrainian Soviet republic. The

The Ukrainian national idea lived on during the inter-war years and was even spread to a large territory with the traditionally mixed population in the east and south that became part of the Ukrainian Soviet republic. The Ukrainian culture

The culture of Ukraine is the composite of the material and spiritual values of the Ukrainian people that has formed throughout the history of Ukraine. It is closely intertwined with ethnic studies about ethnic Ukrainians and Ukrainian histor ...

even enjoyed a revival due to Bolshevik concessions in the early Soviet years (until the early-1930s) known as the policy of Korenization

Korenizatsiia or korenization ( rus, коренизация, p=kərʲɪnʲɪˈzatsɨjə, , "indigenization") was an early policy of the Soviet Union for the integration of non-Russian nationalities into the governments of their specific Soviet ...

("indigenization"). In these years, an impressive Ukrainization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

program was implemented throughout the republic. Alongside this a number of national territorial units were set aside for non-Ukrainian ethnic groups. As well as an autonomous republic in the west for Ukraine's Molovian people several national raions including 8 Russian, 7 German, 4 Greek, 4 Bulgarian, 3 Jewish and 1 Polish national raion existed in this period.

The rapidly developed Ukrainian language-based education system dramatically raised the literacy of the Ukrainophone rural population. Simultaneously, the newly literate ethnic Ukrainians migrated to the cities, which became rapidly largely Ukrainianised—in both population and in education. Similarly expansive was an increase in Ukrainian language publishing and overall eruption of Ukrainian cultural life.

At the same time, the usage of Ukrainian was continuously encouraged in the workplace and in government affairs as the recruitment of indigenous cadre was implemented as part of the korenisation policies. While initially, the party and government apparatus was mostly Russian-speaking, by the end of the 1920s the ethnic Ukrainians composed over one half of the membership in the Ukrainian communist party, the number strengthened by the accession of Borotbists

The Borotbists (Fighters) (1918–1920) was a left-nationalist political party in Ukraine. It is not be associated with its Russian affiliated counterparts - the Ukrainian Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Borbysts) and the Ukrainian Comm ...

, a formerly indigenously Ukrainian "independentist" and non-Bolshevik communist party.

Despite the ongoing Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

-wide antireligious campaign, the Ukrainian national Orthodox church was created called the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, Українська автокефальна православна церква (УАПЦ), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

(UAOC). The Bolshevik government initially saw the national church as a tool in their goal to suppress the Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

always viewed with the great suspicion by the regime for its being the cornerstone of pre-revolutionary Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

and the initially strong opposition it took towards the regime change. Therefore, the government tolerated the new Ukrainian national church for some time and the UAOC gained a wide following among the Ukrainian peasantry.

The change in the Soviet economic policies towards the fast-pace

The change in the Soviet economic policies towards the fast-pace industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

was marked by the 1928 introduction of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's first piatiletka (a five-year plan). Industrialization brought about a dramatic economic and social transformation in traditionally agricultural Ukraine. In the first piatiletkas the industrial output of Ukraine quadrupled as the republic underwent a record industrial development. The massive influx of the rural population to the industrial centers increased the urban population from 19% to 34%.

Soviet collectivisation

However, industrialization had a heavy cost for the peasantry, demographically a backbone of the Ukrainian nation. To satisfy the state's need for increased food supplies and finance industrialization, Stalin instituted a program of collectivization of agriculture, which profoundly affected Ukraine, often referred to as the "breadbasket of the USSR". In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the state combined the peasants' lands and animals into collective farms. Starting in 1929, a policy of enforcement was applied, using regular troops and secret police to confiscate lands and materials where necessary. Many resisted, and a desperate struggle by the peasantry against the authorities ensued. Some slaughtered their livestock rather than turn it over to the collectives. Wealthier peasants were labeled "kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

s", enemies of the state. Tens of thousands were executed and about 100,000 families were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan.

Forced collectivization had a devastating effect on agricultural productivity. Despite this, in 1932 the Soviet government increased Ukraine's production quotas by 44%, ensuring that they could not be met. Soviet law required that the members of a collective farm would receive no grain until government quotas were satisfied. The authorities in many instances exacted such high levels of procurement from collective farms that starvation became widespread.

The

The Soviet famine of 1932–33

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, called Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

in Ukrainian, claimed up to 10 million Ukrainian lives as peasants' food stocks were forcibly removed by Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

's regime by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

secret police. As elsewhere, the precise number of deaths by starvation in Ukraine may never be precisely known. That said, the most recent demographic studies suggest that over 4 million Ukrainians perished in the first six months of 1933 alone, a figure that increases if population losses from 1931, 1932 and 1934 are also included, along with those from adjacent territories inhabited primarily by Ukrainians (but politically part of the Russian Federated Soviet Socialist Republic), such as the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ady, Пшызэ) is a historical and geographical region of Southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and the Caucasus, and separated ...

.

The Soviet Union suppressed information about this genocide, and as late as the 1980s admitted only that there was some hardship because of kulak sabotage and bad weather. Non-Soviets maintain that the famine was an avoidable, deliberate act of genocide.

The times of industrialization and collectivization also brought about a wide campaign against "nationalist deviation" which in Ukraine translated into an assault on the national political and cultural elite. The first wave of purges between 1929 and 1934 targeted the revolutionary generation of the party that in Ukraine included many supporters of Ukrainization

Ukrainization (also spelled Ukrainisation), sometimes referred to as Ukrainianization (or Ukrainianisation) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of ...

. The next 1936–1938 wave of political purges eliminated much of the new political generation that replaced those that perished in the first wave and halved the membership of the Ukrainian communist party.Encyclopædia BritannicaUkraine

article, page 51. The purged Ukrainian political leadership was largely replaced by the cadre sent from

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

that was also largely "rotated" by Stalin's purges. As the policies of Ukrainisation were halted (1931) and replaced by massive Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cult ...

approximately four-fifths of the Ukrainian cultural elite, intellectuals, writers, artists and clergy, had been "eliminated", executed or imprisoned, in the following decade. Mass arrests of the hierarchy and clergy of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

The Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church (UAOC; uk, Українська автокефальна православна церква (УАПЦ), Ukrayinska avtokefalna pravoslavna tserkva (UAPC)) was one of the three major Eastern Orthod ...

culminated in the liquidation of the church in 1930.

Galicia and Volhynia under Polish rule

Following the end of World War I, the eastern part of the former Austrian province of

Following the end of World War I, the eastern part of the former Austrian province of Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, as well as Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, which had belonged to the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, became the area of a Polish-Ukrainian War. The Ukrainians claimed these lands because they made up the majority of the population there (except for cities, such as Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

), while the Poles saw these provinces as Eastern Borderlands

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic, it ...

, a historical part of their country. The war was won by the Poles, and their rule over these disputed lands was cemented after another Polish victory, in the Polish-Soviet War. While some Ukrainians supported Poland, their hopes for independence or autonomy were quickly dashed.

In the interbellum period, eastern Galicia was divided into three administrative units

Administrative division, administrative unit,Article 3(1). country subdivision, administrative region, subnational entity, constituent state, as well as many similar terms, are generic names for geographical areas into which a particular, ind ...

— Lwów Voivodeship

Lwów Voivodeship ( pl, Województwo lwowskie) was an administrative unit of interwar Poland (1918–1939). Because of the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland in accordance with the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, it became occupied by both the Weh ...

, Stanisławów Voivodeship

Stanisławów Voivodeship ( pl, Województwo stanisławowskie) was an administrative district of the interwar Poland (1920–1939). It was established in December 1920 with an administrative center in Stanisławów. The voivodeship had an area o ...

, and Tarnopol Voivodeship, while in Volhynia, Wołyń Voivodeship was created. The Ukrainian majority of these lands was often treated as second-class citizens by the Polish authorities. The conflict escalated in the 1930s, with terrorist actions of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists ( uk, Організація українських націоналістів, Orhanizatsiya ukrayins'kykh natsionalistiv, abbreviated OUN) was a Ukrainian ultranationalist political organization esta ...

resulting in increasingly heavy-handed actions by the Polish government. The tensions were further exacerbated by the arrival of thousands of osadnik

Osadniks ( pl, osadnik/osadnicy, "settler/settlers, colonist/colonists") were veterans of the Polish Army and civilians who were given or sold state land in the ''Kresy'' (current Western Belarus and Western Ukraine) territory ceded to Poland by P ...

s, or Polish settlers, who were granted land, especially in Volhynia. Henryk Józewski

Henryk Jan Józewski (Kyiv, August 6, 1892 - April 23, 1981, Warsaw) was a Polish visual artist, politician, a member of government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, later an administrator during the Second Polish Republic.

A member of Polish-in ...

advocated a self-governance autonomy for Ukrainians in Volhynia 1928–1938.

Polish rule over the provinces ended in September 1939, following Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

and Soviet attack. After the Battle of Lviv, units of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

entered regional capital, Lviv, and following the staged Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, both eastern Galicia and Volhynia were annexed by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

A few days after the Germans invaded Poland, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

told an aide his long-term goal was the spread of Communism in Eastern Europe:

Now olandis a fascist state, oppressing the Ukrainians, Belorussians and so forth. The annihilation of that state under current conditions would mean one fewer bourgeois fascist state to contend with! What would be the harm if as a result of the rout off Poland we were to extend the socialist system onto new territories and populations.Historian

Geoffrey Roberts

Geoffrey Roberts (born 1952) is a British historian of World War II working at University College Cork. He specializes in Soviet diplomatic and military history of World War II. He was professor of modern history at University College Cork (UC ...

notes that the comments marked a change from the previous "popular front" policy of Communist Party cooperation with other parties. He adds, "Stalin's immediate purpose was to present an ideological rationale for the Red Army's forthcoming invasion of Poland" and his main message was the need to avoid a revolutionary civil war." Historian Timothy D. Snyder suggests that, "Stalin may have reasoned that returning Galicia and Volhynia to Soviet Ukraine would help co-opt Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French ...

. Stalin perhaps saw a way to give both Ukrainians and Poles something they wanted, while binding them to the USSR."

World War II

Following the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland, including

Following the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland, including Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

with its Ukrainian population. Next, after France surrendered to Germany, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

ceded Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

and northern Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter Berge ...

to Soviet demands. The Ukrainian SSR incorporated northern and southern districts of Bessarabia, the northern Bukovina, and additionally the Soviet-occupied Hertsa region

The Hertsa region, also known as the Hertza region ( uk, Край Герца, Kraj Herca; ro, Ținutul Herța), is a region around the town of Hertsa within Chernivtsi Raion in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, n ...

, but ceded the western part of the Moldavian ASSR

* ro, Proletari din toate țările, uniți-vă! (Moldovan Cyrillic: )

* uk, Пролетарі всіх країн, єднайтеся!

* russian: Пролетарии всех стран, соединяйтесь!

, title_leader = First Secr ...

to the newly created Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic ( ro, Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească, Moldovan Cyrillic: ) was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union which existed from 1940 to 1991. The republic was formed on 2 August 1940 ...

. All these territorial gains were internationally recognized by the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

The Paris Peace Treaties (french: Traités de Paris) were signed on 10 February 1947 following the end of World War II in 1945.

The Paris Peace Conference lasted from 29 July until 15 October 1946. The victorious wartime Allied powers (princi ...

.

When Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

with its allies invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, many Ukrainians and Polish people, particularly in the west where they had experienced two years of harsh Soviet rule, initially regarded the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

soldiers as liberators. Retreating Soviets murdered thousands of prisoners. Some Ukrainian activists of the national movement hoped for momentum to establish an independent state of Ukraine. German policies initially gave some encouragement to such hopes through the vague promises of sovereign 'Greater Ukraine' as the Germans were trying to take advantage of anti-Soviet, anti-Ukrainian, anti-Polish, and anti-Jewish sentiments. A local Ukrainian auxiliary police was formed as well as Ukrainian SS division, 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Galicia (1st Ukrainian)

The 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) (german: 14. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS alizische Nr. 1}; uk, 14а Гренадерська Дивізія СС (1а галицька)), known as the 14th SS-Volunteer Division ...

. However, after the initial period of limited tolerance, the German policies soon abruptly changed and the Ukrainian national movement was brutally crushed.

Some Ukrainians, however, utterly resisted the Nazi onslaught from its start and a partisan movement immediately spread over the occupied territory. Some elements of the Ukrainian nationalist underground formed a Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army ( uk, Українська повстанська армія, УПА, translit=Ukrayins'ka povstans'ka armiia, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and later partisan formation. During World ...

that fought both Soviet and Nazi forces. In some western regions of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army survived underground and continued the resistance against the Soviet authorities well into the 1950s, though many Ukrainian civilians were murdered in this conflict by both sides.

The Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population's possible dissatisfaction with Soviet political and economic policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, and deported many Ukrainians to forced labour in Germany. In their active resistance to Nazi Germany, the Ukrainians comprised a significant share of the Red Army and its leadership as well as the underground and resistance movements.

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at seven million, including over a million Jews shot and killed by the ''

The Nazi administrators of conquered Soviet territories made little attempt to exploit the population's possible dissatisfaction with Soviet political and economic policies. Instead, the Nazis preserved the collective-farm system, systematically carried out genocidal policies against Jews, and deported many Ukrainians to forced labour in Germany. In their active resistance to Nazi Germany, the Ukrainians comprised a significant share of the Red Army and its leadership as well as the underground and resistance movements.

Total civilian losses during the war and German occupation in Ukraine are estimated at seven million, including over a million Jews shot and killed by the ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

''.

Many civilians fell victim to atrocities, forced labor, and even massacres of whole villages in reprisal for attacks against Nazi forces. Of the estimated eleven million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis, about 16% (1.7 million) were ethnic Ukrainians. Moreover, Ukraine saw some of the biggest battles of the war starting with the encirclement of Kyiv (the city itself fell to the Germans on 19 September 1941 and was later acclaimed as a ''

Many civilians fell victim to atrocities, forced labor, and even massacres of whole villages in reprisal for attacks against Nazi forces. Of the estimated eleven million Soviet troops who fell in battle against the Nazis, about 16% (1.7 million) were ethnic Ukrainians. Moreover, Ukraine saw some of the biggest battles of the war starting with the encirclement of Kyiv (the city itself fell to the Germans on 19 September 1941 and was later acclaimed as a ''Hero City Hero City may refer to:

* Hero City (Soviet Union), awarded 1965–1985 to cities now in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine

* Hero City of Ukraine, awarded 2022

* Hero Cities of Yugoslavia, awarded 1970–1975

* Leningrad Hero City Obelisk, a monument

...

'') where more than 660,000 Soviet troops were taken captive, to the fierce defense of Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, and on to the victorious storming across the Dnieper river

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

. According to the researcher Rolf Michaelis who is referring to the SS-Hauptamt's document No. 8699/42, the Police Battalion "Ostland" (Field Post Number 47769) resided in the Reichskommissariat Ukraine

During World War II, (abbreviated as RKU) was the civilian occupation regime () of much of Nazi German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of modern-day Belarus and pre-war Second Polish Republic). It was governed by the Reic ...

in 1941–1942, and was one of the main executioners of the Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

s. The Police Battalion "Ostland" was an Ordnungspolizei

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (), abbreviated ''Orpo'', meaning "Order Police", were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo organisation was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction ...

unit that served in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

under the command of the Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe ...

. The battalion established in October 1941 carried out punitive duties.

On June 28, 1941, the town of Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast ( province), as well as the surrounding Rivne ...

(Równe) was captured by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, which later established the city as the administrative center of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine

During World War II, (abbreviated as RKU) was the civilian occupation regime () of much of Nazi German-occupied Ukraine (which included adjacent areas of modern-day Belarus and pre-war Second Polish Republic). It was governed by the Reic ...

. In July 1941 the 1st company of the Police Battalion "Ostland" was in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, the rest of the battalion was in Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast ( province), as well as the surrounding Rivne ...

. In October 1941 the battalion was sent to Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

(Lwów). At the time, roughly half of Równe's inhabitants were Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. About 23,000 of these people were taken to a pine grove in Sosenki and slaughtered by the 1st company of the Police Battalion "Ostland" between November 6, and 8, 1941 (1st company). A ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

was established for the remaining ca 5,000 Jews.Rolf Michaelis, ''Der Einsatz der Ordnungspolizei 1939–1945. Polizei-Bataillone, SS-Polizei-Regimenter''. Michaelis Verlag – Berlin, 2008. Stefan Klemp: ''Nicht ermittelt. Polizeibataillone und die Nachkriegsjustiz. Ein Handbuch.'' 2. Aufl., Klartext, Essen 2011, S. 296–301. As reported on May 11, 1942, ca 1,000 Jews were executed in Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative stat ...

. Wolfgang Curilla: ''Die deutsche Ordnungspolizei und der Holocaust im Baltikum und in Weissrussland, 1941–1944.'' F. Schöningh, Paderborn 2006, .

On July 13–14, 1942, the remaining population of the Równe ghetto – about 5,000 Jews – was sent by train some 70 kilometres north to Kostopil (Kostopol) where they were murdered by the 1st company of the Police Battalion "Ostland" in a quarry near woods outside the town. The Równe ghetto was subsequently liquidated. As reported on July 14, 1942: The battalion or elements of it provided security along with the Ukrainische Hilfspolizei

The ''Ukrainische Hilfspolizei'' or the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police ( ua, Українська допоміжна поліція, Ukrains'ka dopomizhna politsiia) was the official title of the local police formation (a type of hilfspolizei) set up ...

for a transport of the Jews from the Riga Ghetto to the Riga Central Station __NOTOC__

Riga Central Station ( lv, Rīgas Centrālā stacijа) is the main railway station in Riga, Latvia. It is known as the main point of Riga due to its central location, and most forms of public transport stop in this area. Part of the build ...

using the wagons (1st company). July 15, 1942 another thousand Jews were executed in the same place. As reported on June 27, 1942, ca 8,000 Jews were executed near the town of Słonim

Slonim ( be, Сло́нім, russian: Сло́ним, lt, Slanimas, lv, Sloņima, pl, Słonim, yi, סלאָנים, ''Slonim'') is a city in Grodno Region, Belarus, capital of the Slonimski rajon. It is located at the junction of the Šča ...

. As reported on July 28, 1942, ca 6,000 Jews were executed in Minsk.

In November 1942 the Police Battalion Ostland together with an artillery regiment, and three other German Ordnungspolizei

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (), abbreviated ''Orpo'', meaning "Order Police", were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo organisation was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction ...

battalions under the command of ''Befehlshaber der Ordnungspolizei im Reichskommissariat Ukraine'' and ''SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Polizei'' Otto von Oelhafen, took part in a joint anti-partisan operation near Ovruch

Ovruch ( uk, Овруч, pl, Owrucz, yi, , russian: О́вруч) is a city in Korosten Raion, in the Zhytomyr Oblast (province) of northern Ukraine. Prior to 2020, it was the administrative center of the former Ovruch Raion (district). It has ...

(Owrucz) with over 50 villages burnt down and over 1,500 people executed. In a village 40 people were burnt alive for revenge for the killing of the SS-Untersturmführer

(, ; short: ''Ustuf'') was a paramilitary rank of the German ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) first created in July 1934. The rank can trace its origins to the older SA rank of ''Sturmführer'' which had existed since the founding of the SA in 1921. ...

Türnpu(u). In February 1943 the battalion was sent to Reval, Estland with Polizei Füsilier Bataillon 293. By March 31, 1943, the Estnische Legion had 37 officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

s, 175 noncoms and 62 private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

s of the Police Battalion "Ostland".

Kyiv was recaptured by the Soviet Red Army on 6 November 1943.

During a period of March 1943 to the end of 1944 Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army ( uk, Українська повстанська армія, УПА, translit=Ukrayins'ka povstans'ka armiia, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and later partisan formation. During World ...

committed several massacres on the Polish civilian population in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia having every signs of genocide (Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia ( pl, rzeź wołyńska, lit=Volhynian slaughter; uk, Волинська трагедія, lit=Volyn tragedy, translit=Volynska trahediia), were carried out in German-occupied Poland by th ...

). The death toll numbered up to 100 000, mostly children and women.Timothy SnyderA fascist hero in democratic Kiev

. New York Review of Books. February 24, 2010J. P. Himka

Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history

University of Alberta. 28 March 2011. p. 4 Late October 1944 the last territory of current Ukraine (near

Uzhhorod

Uzhhorod ( uk, У́жгород, , ; ) is a city and municipality on the river Uzh in western Ukraine, at the border with Slovakia and near the border with Hungary. The city is approximately equidistant from the Baltic, the Adriatic and the ...

, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

) was cleared of Germany troops; this is annually celebrated in Ukraine (on 28 October) as the " anniversary of the liberation of Ukraine from the Nazis".

Late March 2019 former members of armed units of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists ( uk, Організація українських націоналістів, Orhanizatsiya ukrayins'kykh natsionalistiv, abbreviated OUN) was a Ukrainian ultranationalist political organization esta ...

, former Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army ( uk, Українська повстанська армія, УПА, translit=Ukrayins'ka povstans'ka armiia, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and later partisan formation. During World ...

members and former members of the Polissian Sich/Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army, members of the Ukrainian Military Organization and Carpathian Sich

The Carpathian Sich ( uk, Організація народної оборони Карпатська Січ, Orhanizatsiia narodnoii oborony Karpatska Sich – National Defense Organization Carpathian Sich) This meant that for the first time they could receive veteran benefits, including free public transport, subsidized medical services, annual monetary aid, and public utilities discounts (and will enjoy the same social benefits as former Ukrainian soldiers

,

Law recognizing Ukrainian Insurgent Army fighters as veterans enforced

,

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1979-113-04, Lager Winnica, gefangene Russen.jpg, Vinnytsia, July 1941. Some 2.8 million Soviet POWs were killed in just eight months of 1941–42

File:Einsatzgruppen murder Jews in Ivanhorod, Ukraine, 1942.jpg, Executions of Kyiv

After World War II some amendments to the Constitution of the

After World War II some amendments to the Constitution of the

On January 21, 1990, over 300,000 Ukrainians organised a human chain for Ukrainian independence between

On January 21, 1990, over 300,000 Ukrainians organised a human chain for Ukrainian independence between

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

).Former WWII nationalist guerrillas granted veteran status in Ukraine,

Kyiv Post

The ''Kyiv Post'' is the oldest English-language newspaper in Ukraine, founded in October 1995 by Jed Sunden.

History

American Jed Sunden founded the ''Kyiv Post'' weekly newspaper on Oct. 18, 1995 and later created KP Media for his holdings. ...

(26 March 2019)Law recognizing Ukrainian Insurgent Army fighters as veterans enforced

,

112 Ukraine

112 Ukraine ( uk, 112 Україна) was a private Ukrainian TV channel which provided 24-hour news coverage. 112 Ukraine was available on satellites AMOS 2/3, via the DVB-T2 network, and was also available in packages of all major Ukrainian ca ...

(26 March 2019) (There had been several previous attempts to provide former Ukrainian nationalist fighters with official veteran status, especially during the 2005-2009 administration President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Viktor Yushenko

Viktor Andriyovych Yushchenko ( uk, Віктор Андрійович Ющенко, ; born 23 February 1954) is a Ukrainian politician who was the third president of Ukraine from 23 January 2005 to 25 February 2010.

As an informal leader of th ...

, but all failed.)

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

by German army mobile killing units (Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

) near Ivangorod

Ivangorod ( rus, Иванго́род, p=ɪvɐnˈɡorət; et, Jaanilinn; vot, Jaanilidna) is a town in Kingiseppsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the east bank of the Narva river which flows along the Estonia–Russia int ...

, 1942

File:Cherkaschyna deportation 1942.jpg, Ukrainians being deported to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

for forced labor, 1942

File:Lipikach.jpg, Massacres of Poles in Volhynia

The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia ( pl, rzeź wołyńska, lit=Volhynian slaughter; uk, Волинська трагедія, lit=Volyn tragedy, translit=Volynska trahediia), were carried out in German-occupied Poland by the ...

in 1943

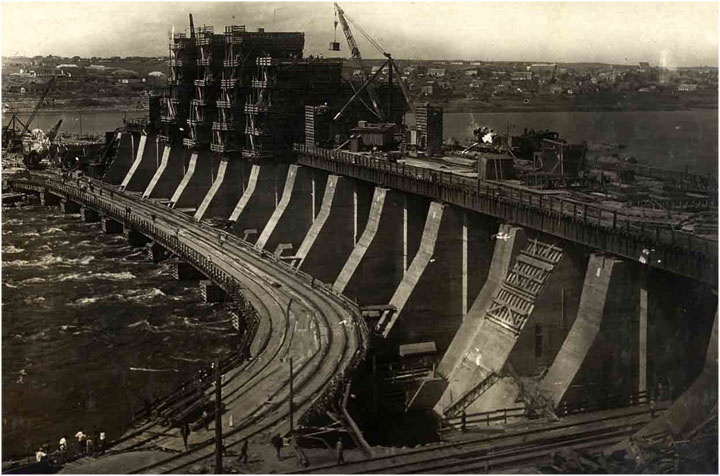

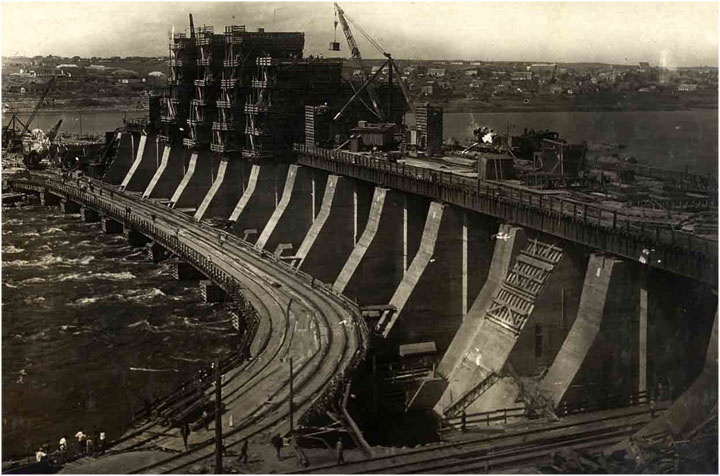

File:ZaporizhiaCombat.jpg, Battle of the dam in Zaporizhia, 1943

Post-war (1945–91)

After World War II some amendments to the Constitution of the

After World War II some amendments to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

were accepted, which allowed it to act as a separate subject of international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

in some cases and to a certain extent, remaining a part of the Soviet Union at the same time. In particular, these amendments allowed the Ukrainian SSR to become one of founding members of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

(UN) together with the Soviet Union and the Byelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

. This was part of a deal with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

to ensure a degree of balance in the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

, which, the USSR opined, was unbalanced in favor of the Western Bloc. In its capacity as a member of the UN, the Ukrainian SSR was an elected member of the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

in 1948–1949 and 1984–1985.

Over the next decades, the Ukrainian republic not only surpassed pre-war levels of industry and production but also was the spearhead of Soviet power. Ukraine became the centre of Soviet arms industry