Mithradates VI of Pontus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης; 135–63 BC) was ruler of the

Mithridates Eupator Dionysus ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης Εὐπάτωρ Δῐόνῡσος) was a prince of mixed

Mithridates Eupator Dionysus ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης Εὐπάτωρ Δῐόνῡσος) was a prince of mixed

The next ruler of Bithynia,

The next ruler of Bithynia,

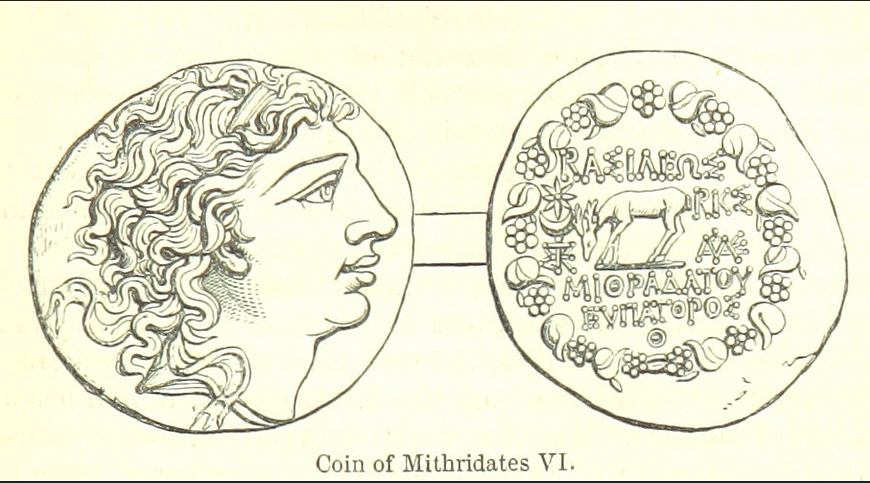

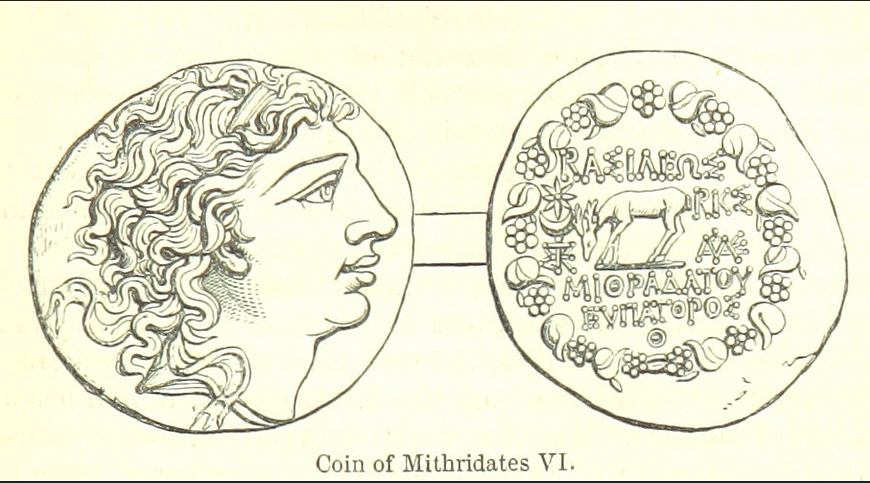

Where his ancestors pursued philhellenism as a means of attaining respectability and prestige among the Hellenistic kingdoms, Mithridates VI made use of Hellenism as a political tool. Greeks, Romans and Asians were welcome at his court. As protector of Greek cities on the Black Sea and in Asia against barbarism, Mithridates VI logically became protector of Greece and Greek culture, and used this stance in his clashes with Rome. Strabo mentions that Chersonesus buckled under the pressure of the barbarians and asked Mithridates VI to become its protector (7.4.3. c.308). The most impressive symbol of Mithridates VI's approbation with Greece (Athens in particular) appears at Delos: a heroon dedicated to the Pontic king in 102/1 by the Athenian Helianax, a priest of Poseidon Aisios. A dedication at Delos, by Dicaeus, a priest of Sarapis, was made in 94/93 BC on behalf of the Athenians, Romans, and "King Mithridates Eupator Dionysus". Greek styles mixed with Persian elements also abound on official Pontic coins – Perseus was favored as an intermediary between both worlds, East and West.

Certainly influenced by

Where his ancestors pursued philhellenism as a means of attaining respectability and prestige among the Hellenistic kingdoms, Mithridates VI made use of Hellenism as a political tool. Greeks, Romans and Asians were welcome at his court. As protector of Greek cities on the Black Sea and in Asia against barbarism, Mithridates VI logically became protector of Greece and Greek culture, and used this stance in his clashes with Rome. Strabo mentions that Chersonesus buckled under the pressure of the barbarians and asked Mithridates VI to become its protector (7.4.3. c.308). The most impressive symbol of Mithridates VI's approbation with Greece (Athens in particular) appears at Delos: a heroon dedicated to the Pontic king in 102/1 by the Athenian Helianax, a priest of Poseidon Aisios. A dedication at Delos, by Dicaeus, a priest of Sarapis, was made in 94/93 BC on behalf of the Athenians, Romans, and "King Mithridates Eupator Dionysus". Greek styles mixed with Persian elements also abound on official Pontic coins – Perseus was favored as an intermediary between both worlds, East and West.

Certainly influenced by

Ch. XXV, §§5–7

like

''Mitrídates ha muerto''

, Ignasi Ribó traces parallels between the historical figures of Mithridates and Osama Bin Laden. Within a postmodern narrative of the making and unmaking of history, Ribó suggests that the

''Mitrídates ha muerto''

Madrid, Bubok, 2010, * Mayor, Adrienne, ''The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy'' (Princeton, PUP, 2009). * Madsen, Jesper Majbom, Mithradates VI : Rome's perfect enemy. In: ''Proceedings of the Danish Institute in Athens'' Vol. 6, 2010, pp. 223–237. * Ballesteros Pastor, Luis, ''Pompeyo Trogo, Justino y Mitrídates. Comentario al'' Epítome de las Historias Filípicas ''(37,1,6–38,8,1)'' (''Spudasmata'' 154), Hildesheim-Zürich-New York, Georg Olms Verlag, 2013, .

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mithridates 06 Eupator 135 BC births 63 BC deaths 2nd-century BC Iranian people 1st-century BC Iranian people 1st-century BC rulers in Asia Achaemenid dynasty Ancient child rulers Ancient Pontic Greeks Deaths by blade weapons Iranian people of Greek descent Mithridatic Wars Mithridatic kings of Pontus Rulers of the Bosporan Kingdom

Kingdom of Pontus

Pontus ( grc-gre, Πόντος ) was a Hellenistic kingdom centered in the historical region of Pontus and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty (of Persian origin), which possibly may have been directly related to Darius the Great of the Achaemen ...

in northern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

's most formidable and determined opponents. He was an effective, ambitious and ruthless ruler who sought to dominate Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

region, waging several hard-fought but ultimately unsuccessful wars (the Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were three conflicts fought by Rome against the Kingdom of Pontus and its allies between 88 BC and 63 BC. They are named after Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus who initiated the hostilities after annexing the Roman provi ...

) to break Roman dominion over Asia and the Hellenic world. He has been called the greatest ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus. He cultivated an immunity to poisons by regularly ingesting sub-lethal doses; this practice, now called mithridatism

Mithridatism is the practice of protecting oneself against a poison by gradually self-administering non-lethal amounts. The word is derived from Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus, who so feared being poisoned that he regularly ingested small dos ...

, is named after him. After his death he became known as Mithridates the Great.

Etymology

''Mithridates'' is theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

attestation of the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

name ''Mihrdāt'', meaning "given by Mithra

Mithra ( ae, ''Miθra'', peo, 𐎷𐎰𐎼 ''Miça'') commonly known as Mehr, is the Iranian deity of covenant, light, oath, justice and the sun. In addition to being the divinity of contracts, Mithra is also a judicial figure, an all-seein ...

", the name of the ancient Iranian sun god. The name itself is derived from Old Iranian

The Iranian languages or Iranic languages are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

The Iranian languages are grouped ...

''Miθra-dāta-''.

Ancestry, family and early life

Mithridates Eupator Dionysus ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης Εὐπάτωρ Δῐόνῡσος) was a prince of mixed

Mithridates Eupator Dionysus ( grc-gre, Μιθραδάτης Εὐπάτωρ Δῐόνῡσος) was a prince of mixed Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ancestry. He claimed descent from Cyrus the Great, the family of Darius the Great, the Regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

Antipater, the generals of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

as well as the later kings Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

.

Mithridates was born in the Pontic city of Sinope, on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia, and was raised in the Kingdom of Pontus

Pontus ( grc-gre, Πόντος ) was a Hellenistic kingdom centered in the historical region of Pontus and ruled by the Mithridatic dynasty (of Persian origin), which possibly may have been directly related to Darius the Great of the Achaemen ...

. He was the first son among the children born to Laodice VI Laodice VI ( el, Λαοδίκη ΣΤ΄; died 115–113 BCE) was a Greek Seleucid princess and through marriage was a queen of the Kingdom of Pontus.

Biography

Laodice was the daughter born from the sibling union of the Seleucid rulers Antiochus IV ...

and Mithridates V Euergetes (reigned 150–120 BC). His father, Mithridates V, was a prince and the son of the former Pontic monarchs Pharnaces I of Pontus

Pharnaces I ( el, Φαρνάκης; lived 2nd century BC), fifth king of Pontus, was of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the son of King Mithridates III of Pontus and his wife Laodice, whom he succeeded on the throne. Pharnaces had two sibli ...

and his cousin-wife Nysa. His mother, Laodice VI, was a Seleucid princess and the daughter of the Seleucid monarchs Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes (; grc, Ἀντίοχος ὁ Ἐπιφανής, ''Antíochos ho Epiphanḗs'', "God Manifest"; c. 215 BC – November/December 164 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king who ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his dea ...

and his sister-wife Laodice IV

Laodice IV (flourished second half 3rd century BC and first half 2nd century BC) was a Greek Princess, Head Priestess and Queen of the Seleucid Empire. Antiochus III appointed Laodice in 193 BC, as the chief priestess of the state cult dedicated ...

.

Mithridates V was assassinated in about 120 BC in Sinope, poisoned by unknown persons at a lavish banquet which he held. He left the kingdom to the joint rule of his widow Laodice VI, and their elder son Mithridates VI, and younger son Mithridates Chrestus. Neither Mithridates VI nor his younger brother were of age, and their mother retained all power as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

for the time being. Laodice VI's regency over Pontus was from 120 BC to 116 BC (even perhaps up to 113 BC) and favored Mithridates Chrestus over Mithridates. During his mother's regency, Mithridates escaped from his mother's plots against him and went into hiding.

Mithridates emerged from hiding and returned to Pontus between 116 and 113 BC and was hailed as king. By this time he had grown to become a man of considerable stature and physical strength. He could combine extraordinary energy and determination with a considerable talent for politics, organization and strategy. Mithridates removed his mother and brother from the throne, imprisoning both, becoming the sole ruler of Pontus.Mayor, p. 394 Laodice VI died in prison, ostensibly of natural causes. Mithridates Chrestus may have died in prison also, or may have been tried for treason and executed. Mithridates gave both royal funerals. Mithridates took his younger sister Laodice, aged 16, as his first wife. His goals in doing so were to preserve the purity of their bloodline, to solidify his claim to the throne, to co-rule over Pontus, and to ensure the succession to his legitimate children.

Early reign

Mithridates entertained ambitions of making his state the dominant power on theBlack Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. He first subjugated Colchis

In Greco-Roman geography, Colchis (; ) was an exonym for the Georgian polity of Egrisi ( ka, ეგრისი) located on the coast of the Black Sea, centered in present-day western Georgia.

Its population, the Colchians are generally though ...

, a region east of the Black Sea occupied by present-day Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and prior to 164 BC, an independent kingdom. He then clashed for supremacy on the Pontic steppe with the Scythian

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Centra ...

king Palacus. The most important centres of Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, Tauric Chersonesus

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the ...

and the Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

readily surrendered their independence in return for Mithridates' promises to protect them against the Scythians, their ancient enemies. After several abortive attempts to invade the Crimea, the Scythians and the allied Rhoxolanoi suffered heavy losses at the hands of the Pontic general Diophantus and accepted Mithridates as their overlord.

The young king then turned his attention to Anatolia, where Roman power was on the rise. He contrived to partition Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia (; el, Παφλαγονία, Paphlagonía, modern translit. ''Paflagonía''; tr, Paflagonya) was an ancient region on the Black Sea coast of north-central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus (region), Pontus t ...

and Galatia with King Nicomedes III of Bithynia

Nicomedes III Euergetes ("the Benefactor", grc-gre, Νικομήδης Εὐεργέτης) was the king of Bithynia, from c. 127 BC to c. 94 BC. He was the son and successor of Nicomedes II of Bithynia.

Life

Memnon of Heraclea wrote that Nic ...

. It was probably on the occasion of the Paphlagonian invasion of 108 BC that Mithridates adopted the Bithynian era for use on his coins in honour of the alliance. This calendar era began with the first Bithynian king Zipoites I in 297 BC. It was certainly in use in Pontus by 96 BC at the latest.Jakob Munk Højte, "From Kingdom to Province: Reshaping Pontos after the Fall of Mithridates VI", in Tønnes Bekker-Nielsen (ed.), ''Rome and the Black Sea Region: Domination, Romanisation, Resistance'' (Aarhus University Press, 2006), 15–30.

Yet it soon became clear to Mithridates that Nicomedes was steering his country into an anti-Pontic alliance with the expanding Roman Republic. When Mithridates fell out with Nicomedes over control of Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

, and defeated him in a series of battles, the latter was constrained to openly enlist the assistance of Rome. The Romans twice interfered in the conflict on behalf of Nicomedes (95–92 BC), leaving Mithridates, should he wish to continue the expansion of his kingdom, with little choice other than to engage in a future Roman-Pontic war. By this time Mithridates had resolved to expel the Romans from Asia.

Mithridatic Wars

The next ruler of Bithynia,

The next ruler of Bithynia, Nicomedes IV of Bithynia

Nicomedes IV Philopator ( grc-gre, Νικομήδης Φιλοπάτωρ) was the king of Bithynia from c. 94 BC to 74 BC. (''numbered as III. not IV.'') He was the first son and successor of Nicomedes III of Bithynia.

Life

Memnon of Heraclea wro ...

, was a figurehead

In politics, a figurehead is a person who ''de jure'' (in name or by law) appears to hold an important and often supremely powerful title or office, yet ''de facto'' (in reality) exercises little to no actual power. This usually means that they ...

manipulated by the Romans. Mithridates plotted to overthrow him, but his attempts failed and Nicomedes IV, instigated by his Roman advisors, declared war on Pontus. Rome itself was at the time involved in the Social War, a civil war with its Italian allies; as a result, there were only two legions present in all of Roman Asia, both in Macedonia. These legions combined with Nicomedes IV's army to invade Mithridates' Kingdom of Pontus in 89 BC. Mithridates won a decisive victory, scattering the Roman-led forces. His victorious forces were welcomed throughout Anatolia. The following year, 88 BC, Mithridates orchestrated a genocide of Roman and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

settlers remaining in several major Anatolian cities, including Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

and Tralles, essentially wiping out the Roman presence in the region. As many as 80,000 people are said to have perished in the massacre. The episode is known as the Asiatic Vespers

The Asiatic Vespers (also known as the Asian Vespers, Ephesian Vespers, or the Vespers of 88 BC) refers to the massacres of Roman and other Latin-speaking peoples living in parts of western Anatolia in 88 BC by forces loyal to Mithridates VI Eupat ...

.Mayor

The Kingdom of Pontus comprised a mixed population in its Ionian Greek

Ionic Greek ( grc, Ἑλληνικὴ Ἰωνική, Hellēnikē Iōnikē) was a subdialect of the Attic–Ionic or Eastern dialect group of Ancient Greek.

History

The Ionic dialect appears to have originally spread from the Greek mainland acr ...

and Anatolian cities. The royal family moved the capital from Amasia to the Greek city of Sinope. Its rulers tried to fully assimilate the potential of their subjects by showing a Greek face to the Greek world and an Iranian/Anatolian face to the Eastern world. Whenever the gap between the rulers and their Anatolian subjects became greater, they would put emphasis on their Persian origins. In this manner, the royal propaganda claimed heritage both from Persian and Greek rulers, including Cyrus the Great, Darius I of Persia, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

. Mithridates too posed as a champion of Hellenism, but this was mainly to further his political ambitions; it is no proof that he felt a mission to promote its extension within his domains. Whatever his true intentions, the Greek cities (including Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

) defected to the side of Mithridates and welcomed his armies in mainland Greece, while his fleet besieged the Romans at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

. His neighbor to the southeast, the King of Armenia Tigranes the Great

Tigranes II, more commonly known as Tigranes the Great ( hy, Տիգրան Մեծ, ''Tigran Mets''; grc, Τιγράνης ὁ Μέγας ''Tigránes ho Mégas''; la, Tigranes Magnus) (140 – 55 BC) was King of Armenia under whom the ...

, established an alliance with Mithridates and married one of Mithridates’ daughters, Cleopatra of Pontus. The two rulers would continue to support each other in the coming conflict with Rome.

The Romans responded to the massacre of 88 BC by organising a large invasion force to defeat Mithridates and remove him from power. The First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War (89–85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule were led by Mithridates ...

, fought between 88 and 84 BC, saw Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history and became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force.

Sulla ha ...

force Mithridates out of Greece proper. After achieving victory in several battles, Sulla received news of trouble back in Rome posed by his rival Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbric and Jugurthine wars, he held the office of consul an unprecedented seven times during his career. He was also noted for his important refor ...

and hurriedly concluded peace talks with Mithridates. As Sulla returned to Italy, Lucius Licinius Murena was left in charge of Roman forces in Anatolia. The lenient peace treaty, which was never ratified by the Senate, allowed Mithridates VI to restore his forces. Murena attacked Mithridates in 83 BC, provoking the Second Mithridatic War from 83 to 81 BC. Mithridates defeated Murena's two green legions at the Battle of Halys in 82 BC before peace was again declared by treaty.

When Rome attempted to annex Bithynia (bequested to Rome by its last king) nearly a decade later, Mithridates attacked with an even larger army, leading to the Third Mithridatic War

The Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC), the last and longest of the three Mithridatic Wars, was fought between Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. Both sides were joined by a great number of allies dragging the entire east of the ...

from 73 BC to 63 BC. Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus (; 118–57/56 BC) was a Roman general and statesman, closely connected with Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In culmination of over 20 years of almost continuous military and government service, he conquered the eastern kingd ...

was sent against Mithridates and the Romans routed the Pontic forces at the Battle of Cabira

The Battle of Cabira was fought in 72 or 71 BC between forces of the Roman Republic under proconsul Lucius Licinius Lucullus and those of the Kingdom of Pontus under Mithridates the Great. It was a decisive Roman victory.

Background

Rome had ...

in 72 BC, driving Mithridates into exile in Tigranes' Armenia. While Lucullus was preoccupied fighting the Armenians, Mithridates surged back to retake Pontus by crushing four Roman legions under Valerius Triarius and killing 7,000 Roman soldiers at the Battle of Zela in 67 BC. He was routed by Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

's legions at the Battle of the Lycus in 66 BC.

After this defeat, Mithridates fled with a small army to Colchis and then over the Caucasus Mountains to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

and made plans to raise yet another army to take on the Romans. His eldest living son, Machares, viceroy of Cimmerian Bosporus, was unwilling to aid his father. Mithridates had Machares killed, and Mithridates took the throne of the Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

. He then ordered conscription and preparations for war. In 63 BC, another of his sons, Pharnaces II of Pontus

Pharnaces II of Pontus ( grc-gre, Φαρνάκης; about 97–47 BC) was the king of the Bosporan Kingdom and Kingdom of Pontus until his death. He was a monarch of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the youngest child born to King Mithrida ...

, led a rebellion against his father, joined by Roman exiles in the core of Mithridates' Pontic army. Mithridates withdrew to the citadel in Panticapaeum, where he committed suicide. Pompey buried Mithridates in the rock-cut tombs of his ancestors in Amasia, the old capital of Pontus.

Assassination conspiracy

During the time of the First Mithridatic War, a group of Mithridates' friends plotted to kill him. These were Mynnio and Philotimus ofSmyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, and Cleisthenes and Asclepiodotus of Lesbos. Asclepiodotus changed his mind and became an informant. He arranged to have Mithridates hide under a couch to hear the plot against him. The other conspirators were tortured and executed. Mithridates also killed all of the plotters' families and friends.

Representation of power

Where his ancestors pursued philhellenism as a means of attaining respectability and prestige among the Hellenistic kingdoms, Mithridates VI made use of Hellenism as a political tool. Greeks, Romans and Asians were welcome at his court. As protector of Greek cities on the Black Sea and in Asia against barbarism, Mithridates VI logically became protector of Greece and Greek culture, and used this stance in his clashes with Rome. Strabo mentions that Chersonesus buckled under the pressure of the barbarians and asked Mithridates VI to become its protector (7.4.3. c.308). The most impressive symbol of Mithridates VI's approbation with Greece (Athens in particular) appears at Delos: a heroon dedicated to the Pontic king in 102/1 by the Athenian Helianax, a priest of Poseidon Aisios. A dedication at Delos, by Dicaeus, a priest of Sarapis, was made in 94/93 BC on behalf of the Athenians, Romans, and "King Mithridates Eupator Dionysus". Greek styles mixed with Persian elements also abound on official Pontic coins – Perseus was favored as an intermediary between both worlds, East and West.

Certainly influenced by

Where his ancestors pursued philhellenism as a means of attaining respectability and prestige among the Hellenistic kingdoms, Mithridates VI made use of Hellenism as a political tool. Greeks, Romans and Asians were welcome at his court. As protector of Greek cities on the Black Sea and in Asia against barbarism, Mithridates VI logically became protector of Greece and Greek culture, and used this stance in his clashes with Rome. Strabo mentions that Chersonesus buckled under the pressure of the barbarians and asked Mithridates VI to become its protector (7.4.3. c.308). The most impressive symbol of Mithridates VI's approbation with Greece (Athens in particular) appears at Delos: a heroon dedicated to the Pontic king in 102/1 by the Athenian Helianax, a priest of Poseidon Aisios. A dedication at Delos, by Dicaeus, a priest of Sarapis, was made in 94/93 BC on behalf of the Athenians, Romans, and "King Mithridates Eupator Dionysus". Greek styles mixed with Persian elements also abound on official Pontic coins – Perseus was favored as an intermediary between both worlds, East and West.

Certainly influenced by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, Mithridates VI extended his propaganda from "defender" of Greece to the "great liberator" of the Greek world as war with the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

became inevitable. The Romans were easily translated into "barbarians", in the same sense as the Persian Empire during the war with Persia in the first half of the 5th century BC and during Alexander's campaign. How many Greeks genuinely agreed with this claim will never be known. It served its purpose; at least partially because of it, Mithridates VI was able to fight the First War with Rome on Greek soil, and maintain the allegiance of Greece. His campaign for the allegiance of the Greeks was aided in no small part by his enemy Sulla, who allowed his troops to sack the city of Delphi and plunder many of the city's most famous treasures to help finance his military expenses.

Death

After Pompey defeated him in Pontus, Mithridates VI fled to the lands north of the Black Sea in the winter of 66 BC in the hope that he could raise a new army and carry on the war through invading Italy by way of the Danube. His preparations proved to be too harsh on the local nobles and populace, and they rebelled against his rule. He reportedly attempted suicide by poison, which failed because of his immunity to the substance.A History of Rome, LeGlay, et al. 100 According to Appian's ''Roman History'', he then requested his Gallic bodyguard and friend, Bituitus, to kill him by the sword:Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

's ''Roman History'' records a different account:

At the behest of Pompey, Mithridates' body was later buried alongside his ancestors (in either Sinope or Amaseia). Mount Mithridat

Mount Mithridat is a large hill located in the center of Kerch, a city on the eastern Kerch Peninsula of Crimea. It is in elevation.

From the top of Mount Mithridat a scenic view spreads across the Strait of Kerch and the city of Kerch. Someti ...

in the central Kerch

Kerch ( uk, Керч; russian: Керчь, ; Old East Slavic: Кърчевъ; Ancient Greek: , ''Pantikápaion''; Medieval Greek: ''Bosporos''; crh, , ; tr, Kerç) is a city of regional significance on the Kerch Peninsula in the east of t ...

and the town of Yevpatoria in Crimea commemorate his name.

Mithridates' antidote

In his youth, after the assassination of his father Mithridates V in Mithridates is said to have lived in the wilderness for seven years, inuring himself to hardship. While there and after his accession, he cultivated an immunity to poisons by regularly ingesting sub-lethal doses of poisons, particularly thearsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

that killed his father Mithridates V. This form of hormesis

Hormesis is a characteristic of many biological processes, namely a biphasic or triphasic response to exposure to increasing amounts of a substance or condition. Within the hormetic zone, the biological response to low exposures to toxins and othe ...

is effective against some but not all toxins and subsequently became known as Mithridatism

Mithridatism is the practice of protecting oneself against a poison by gradually self-administering non-lethal amounts. The word is derived from Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus, who so feared being poisoned that he regularly ingested small dos ...

or Mithridatization. After he became king of Pontus, Mithridates continued to study poisons and develop antidotes, whose initial efficacies were tested on Pontic criminals condemned to death. Attalus III

Attalus III ( el, Ἄτταλος Γ΄) Philometor Euergetes ( – 133 BC) was the last Attalid king of Pergamon, ruling from 138 BC to 133 BC.

Biography

Attalus III was the son of king Eumenes II and his queen Stratonice of Pergamon, and ...

of Pergamon

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

(d. 133 BC) is also known to have studied poisons and antidotes in this way. In keeping with most medical practices of his era, Mithridates' antitoxin routines included a religious component; they were supervised by the ''Agari'', a group of Scythian shaman

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spir ...

s who never left him. (He was also reportedly guarded in his sleep by a horse, a bull, and a stag, which would whinny, bellow, and bleat whenever anyone approached the royal bed.) The Greek doctor Crateuas the Rootcutter may have worked directly under Mithridates or may have only been in correspondence with him. Mithridates was also said to have received samples including megalium and kyphi. from Zopyrus of Alexandria and treatises from Asclepiades in lieu of a requested visit. By the time of his death in Mithridates was reported to have developed a complex "universal antidote" against poisoning, which he took every day with cold spring water

A spring is a point of exit at which groundwater from an aquifer flows out on top of Earth's crust ( pedosphere) and becomes surface water. It is a component of the hydrosphere. Springs have long been important for humans as a source of fresh ...

and which became known as mithridate

Mithridate, also known as mithridatium, mithridatum, or mithridaticum, is a semi-mythical remedy with as many as 65 ingredients, used as an antidote for poisoning, and said to have been created by Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus in the 1st cent ...

or mithridatium. He was said to consume it daily. The original formula has been entirely lost, although Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

reports that Mithridates' various antidotes usually included the blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the cir ...

of Pontic ducks (possibly ruddy shelducks), which fed on poisonous plantsPliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

, '' Natural History''Ch. XXV, §§5–7

like

hellebore

Commonly known as hellebores (), the Eurasian genus ''Helleborus'' consists of approximately 20 species of herbaceous or evergreen perennial flowering plants in the family Ranunculaceae, within which it gave its name to the tribe of Helleboreae. ...

and hemlock and thus provided a kind of serum against them. Elsewhere, Pliny reports that surviving notes of Mithridates' work did not include exotic ingredients and that Pompey found an antidote recipe among Mithridates' notes that consisted of 2 dried walnut

A walnut is the edible seed of a drupe of any tree of the genus ''Juglans'' (family Juglandaceae), particularly the Persian or English walnut, '' Juglans regia''.

Although culinarily considered a "nut" and used as such, it is not a true ...

s, 2 figs, and 20 rue

''Ruta graveolens'', commonly known as rue, common rue or herb-of-grace, is a species of ''Ruta'' grown as an ornamental plant and herb. It is native to the Balkan Peninsula. It is grown throughout the world in gardens, especially for its bluis ...

leaves, which were supposed to be crushed together and taken with a pinch of salt by a person who had fasted

Fasting is the abstention from eating and sometimes drinking. From a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (see "Breakfast"), or to the metabolic state achieved after co ...

for at least one day.

The legions under Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

who had defeated Mithridates killed his secretary Callistratus and burnt some of his papers, but were also reported to have taken an extensive medicinal library and collection of specimens back to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where Pompey's slave Lenaeus translated them into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and the Roman doctors like A. Cornelius Celsus began prescribing various recipes under the name of Mithridates' antidote ( la, antidotum Mithridaticum). Numerous recipes survive from the 1st century, all consisting of a polypharmiceutical electuary including castor from willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

-consuming beavers and opium sweetened with honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

Pontic honey tending to contain mild amounts of poison from local plants like rhododendron and oleanderbut otherwise all differing in both ingredients and amounts. It seems likely Pompey and Lenaeus kept Mithridates' personal recipe secret, leading to various attempts to recreate it after their deaths. A foreign father and son both named Paccius seem to have become rich selling their own secret recipe under Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

. Around the same time, Celsus advocated taking an almond-sized amount of his ginger-heavy preparation daily with wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink typically made from fermented grapes. Yeast consumes the sugar in the grapes and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Different varieties of grapes and strains of yeasts are m ...

. Andromachus the Elder, Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unti ...

's court physician, developed theriac

Theriac or theriaca is a medical concoction originally labelled by the Greeks in the 1st century AD and widely adopted in the ancient world as far away as Persia, China and India via the trading links of the Silk Route. It was an alexipharmic, ...

() by supplementing the versions of Mithridates' formula known in his day with more opium, poppy seeds, and a homeopathic

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a dise ...

addition of viper flesh.. One of the vats uncovered at Pompeii seems to have been used to create this version of Mithridates' antidote. Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one ...

added still more opium and a skink in his version of the recipe. Of the plants shared across these early forms of mithridate, many seem to be strongly odoriferous or to exhibit antibacterial

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

and anti-inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory is the property of a substance or treatment that reduces inflammation or swelling. Anti-inflammatory drugs, also called anti-inflammatories, make up about half of analgesics. These drugs remedy pain by reducing inflammation as o ...

abilities; it is also noteworthy that bioactive alkaloids and poisons are ''not'' widely represented.

Mithridate and theriac continued to be staples of Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Islamic medicine

In the history of medicine, "Islamic medicine" is the science of medicine developed in the Middle East, and usually written in Arabic, the ''lingua franca'' of Islamic civilization.

Islamic medicine adopted, systematized and developed the medi ...

into the 19th century, consumed by Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

. and emperors, kings, and queens including Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

, Septimus Severus, Alfred the Great, Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

, Henry VIII, and Queen Elizabeth. Some medieval preparations had as many as 184 ingredients. Owing to the idea that disease could be caused by "internal poisons", the antidotes also came to be thought of as panacea

In Greek mythology, Panacea (Greek ''Πανάκεια'', Panakeia), a goddess of universal remedy, was the daughter of Asclepius and Epione. Panacea and her four sisters each performed a facet of Apollo's art:

* Panacea (the goddess of univers ...

s able to cure damage from falls, some illnesses, or even all illnesses. When it failed, the problem was believed to be improper preparation or storage, leading some jurisdictions to legally require its preparation in full view of the public in city squares.. Concerns about mithridate's purity and later inefficacy were closely involved with the development of medical and pharmaceutical regulation. Mithridate remains available from some doctors, particularly in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

. As early as Pliny

Pliny may refer to:

People

* Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), ancient Roman nobleman, scientist, historian, and author of ''Naturalis Historia'' (''Pliny's Natural History'')

* Pliny the Younger (died 113), ancient Roman statesman, orator, w ...

, however, some considered it quackery

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, ...

and its various components and proportions pseudoscientific. Chinese doctors ''Chinese Doctors'' () is a 2021 Chinese disaster film co-produced, co-cinematographed and directed by Andrew Lau and starring Zhang Hanyu, Yuan Quan, Zhu Yawen, Li Chen, with Jackson Yee and Oho Ou. The film follows the story of frontline medi ...

received samples of mithridate from Muslim ambassadors in the Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdom ...

but never popularized or advocated it. The Islamic scientist Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

, meanwhile, believed it may be helpful in some cases but cautioned against regular consumption by the healthy as it "could actually transform human nature into a kind of poison". It notably failed as a cure to plague and epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of non-communicable neurological disorders characterized by recurrent epileptic seizures. Epileptic seizures can vary from brief and nearly undetectable periods to long periods of vigorous shaking due to abnormal electrica ...

, and William Heberden's 1745 ''Antitheriaca'' ( grc-gre, Αντιθηριακα, ''Antithēriaka'') helped fully discredit it in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. By the 19th century, it was only being prescribed for dyspepsia

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier ...

or described as of historical interest only.

Mithridates as polyglot

InPliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

's account of famous polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Eu ...

s, Mithridates could speak the languages of all the twenty-two nations he governed. This reputation led to the use of Mithridates' name as title in some later works on comparative linguistics, such as Conrad Gessner

Conrad Gessner (; la, Conradus Gesnerus 26 March 1516 – 13 December 1565) was a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist. Born into a poor family in Zürich, Switzerland, his father and teachers quickly realised his tale ...

's ''Mithridates de differentiis linguarum'' (1555), and Adelung and Vater's ''Mithridates oder allgemeine Sprachenkunde'' (1806–1817).

Wives, mistresses and children

Mithridates VI had wives and mistresses, by whom he had several children. The names he gave his children are a representation of his Persian and Greek heritage and ancestry. His first wife was his sister Laodice. They were married from 115/113 BC until about 90 BC. They had several children. Their sons were Mithridates,Arcathius Arcathias ( grc, Ἀρκαθίας) was a Pontic prince of Persian and Greek Macedonian ancestry, and figure in the First Mithridatic War. Arcathias was a son of Mithridates VI of Pontus and his sister-wife Laodice.

In 89 BC, Arcathias joined Ne ...

, Machares and Pharnaces II of Pontus

Pharnaces II of Pontus ( grc-gre, Φαρνάκης; about 97–47 BC) was the king of the Bosporan Kingdom and Kingdom of Pontus until his death. He was a monarch of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the youngest child born to King Mithrida ...

.

Their daughters were Cleopatra of Pontus (sometimes called Cleopatra the Elder to distinguish her from her sister of the same name) and Drypetina

Drypetina, ''Dripetrua'' (died c. 66 BC) was a devoted daughter of King Mithridates VI of Pontus and his sister-wife Laodice.

Biography

Her name is the diminutive form of the name of Drypetis, daughter of the Achaemenid king Darius III. She ha ...

(a diminutive form of "Drypetis

Drypetis (died 323 BCE; sometimes Drypteis) was the daughter of Stateira I and Darius III of Persia. Drypetis was born between 350 and 345 BCE, and, along with her sister Stateira II, was a princess of the Achaemenid dynasty.

Capture and marriage ...

"). Drypetina was Mithridates VI's most devoted daughter. Her baby teeth never fell out, so she had a double set of teeth.

His second wife was a Greek Macedonian noblewoman, Monime. They were married from about 89/88 BC until 72/71 BC and had a daughter, Athenais, who married King Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia

Ariobarzanes II, surnamed ''Philopator'', "father-loving", ( grc, Ἀριοβαρζάνης Φιλοπάτωρ, Ariobarzánēs Philopátōr), was the king of Cappadocia from c. 63 BC or 62 BC to c. 51 BC. He was the son of King Ariobarz ...

. His next two wives were also Greek: he was married to his third wife Berenice of Chios, from 86 to 72/71 BC, and to his fourth wife Stratonice of Pontus, from sometime after 86 to 63 BC. Stratonice bore Mithridates a son Xiphares {{no footnotes, date=November 2018

Xiphares ( grc, Ξιφάρης; c. 85 – 65 BC) was, according to Appian, a Pontic prince who was the son of King Mithridates VI of Pontus from his concubine and later wife Stratonice of Pontus. During the Mithrid ...

. His fifth wife is unknown. His sixth wife Hypsicratea, famed for her loyalty and prowess in battle, was Caucasian, and they were married from an unknown date to 63 BC.

One of his mistresses was the Galatian Celtic princess Adobogiona the Elder. By Adobogiona, Mithridates had two children: a son called Mithridates I of the Bosporus

Mithridates II of the Bosporus, also known as Mithridates of Pergamon (flourished 1st century BC), was a nobleman from Anatolia. Mithridates was one of the sons born to King Mithridates VI of Pontus from his mistress, the Galatian Princess Adobo ...

and a daughter called Adobogiona the Younger

Adobogiona ( fl. c. 70 BC – c. 30 BC) was an illegitimate daughter of king Mithridates VI of Pontus. Her mother was the Galatian princess Adobogiona the Elder. After the death of her father, Adobogiona married the noble Castor Saecondarius, ...

.

His sons born from his concubines were Cyrus, Xerxes, Darius, Ariarathes IX of Cappadocia, Artaphernes, Oxathres, Phoenix (Mithridates' son by a mistress of Syrian descent), and Exipodras, named after kings of the Persian Empire, which he claimed ancestry from. His daughters born from his concubines were Nysa, Eupatra, Cleopatra the Younger, Mithridatis and Orsabaris Orsabaris, also spelt as Orsobaris ( el, , meaning in Persian: ''brilliant Venus'', flourished 1st century BC) was a Princess of the Kingdom of Pontus. She was a Queen of Bithynia by marriage to Socrates Chrestus and later married to Lycomedes of ...

. Nysa and Mithridatis, were engaged to the Egyptian Greek Pharaohs Ptolemy XII Auletes

Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus Philopator Philadelphus ( grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος Νέος Διόνυσος Φιλοπάτωρ Φιλάδελφος, Ptolemaios Neos Dionysos Philopatōr Philadelphos; – 51 BC) was a pharaoh of the Ptolemaic ...

and his brother Ptolemy of Cyprus.

In 63 BC, when the Kingdom of Pontus was annexed by the Roman general Pompey, the remaining sisters, wives, mistresses and children of Mithridates VI in Pontus were put to death. Plutarch, writing in his ''Lives'' (Pompey, v. 45), states that Mithridates' sister and five of his children took part in Pompey's triumphal procession on his return to Rome in 61 BC.

The Cappadocia

Cappadocia or Capadocia (; tr, Kapadokya), is a historical region in Central Anatolia, Turkey. It largely is in the provinces Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde.

According to Herodotus, in the time of the Ionian Re ...

n Greek nobleman and high priest of the temple-state of Comana, Cappadocia

Comana was a city of Cappadocia ( el, τὰ Κόμανα τῆς Καππαδοκίας) and later Cataonia ( la, Comana Cataoniae; frequently called Comana Chryse or Aurea, i.e. "the golden", to distinguish it from Comana in Pontus). The Hittit ...

, Archelaus was descended from Mithridates VI. He claimed to be a son of Mithridates VI; but the chronology suggests that Archelaus may actually have been a maternal grandson of the Pontic king, and the son of Mithridates VI's favourite general, who may have married one of the daughters of Mithridates VI.Mayor, p. 114

Cultural depictions

*The demise of Mithridates VI is detailed in the 1673 play ''Mithridate

Mithridate, also known as mithridatium, mithridatum, or mithridaticum, is a semi-mythical remedy with as many as 65 ingredients, used as an antidote for poisoning, and said to have been created by Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus in the 1st cent ...

'' written by Jean Racine

Jean-Baptiste Racine ( , ) (; 22 December 163921 April 1699) was a French dramatist, one of the three great playwrights of 17th-century France, along with Molière and Corneille as well as an important literary figure in the Western traditi ...

. This play is the basis for several 18th century operas including one of Mozart's earliest, known most commonly by its Italian name, ''Mitridate, re di Ponto

''Mitridate, re di Ponto'' ('' Mithridates, King of Pontus''), K. 87 (74a), is an opera seria in three acts by the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The libretto is by , after Giuseppe Parini's Italian translation of Jean Racine's play '' Mithrida ...

'' (1770).

*Mithridates is the subject of the opera '' Mitridate Eupatore'' (1707) by Alessandro Scarlatti.

*Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

included his "Mithridates" in his 1847 ''Poems''.

* Alexandre Dumas's novel '' The Count of Monte Cristo'' refers to the potential of a mithridate

Mithridate, also known as mithridatium, mithridatum, or mithridaticum, is a semi-mythical remedy with as many as 65 ingredients, used as an antidote for poisoning, and said to have been created by Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontus in the 1st cent ...

as an instrument both of defense and offence.

*William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

, amidst casting about for poetic themes in ''The Prelude

''The Prelude or, Growth of a Poet's Mind; An Autobiographical Poem '' is an autobiographical poem in blank verse by the English poet William Wordsworth. Intended as the introduction to the more philosophical poem ''The Recluse,'' which Wordsw ...

'' (Bk i vv 186 ff):

*James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

alludes to Mithridates' immunity to poison in his love poem ''Though I Thy Mithridates Were''.

*The poet A. E. Housman alludes to Mithridates' antidote in the final stanza of "Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff" in '' A Shropshire Lad'':

* Dorothy L. Sayers' detective novel

Detective fiction is a subgenre of crime fiction and mystery fiction in which an investigator or a detective—whether professional, amateur or retired—investigates a crime, often murder. The detective genre began around the same time as s ...

''Strong Poison

''Strong Poison'' is a 1930 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fifth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the first in which Harriet Vane appears.

Plot

The novel opens with mystery author Harriet Vane on trial for the murder of her forme ...

'', from 1929, has the protagonist, Lord Peter Wimsey

Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey (later 17th Duke of Denver) is the fictional protagonist in a series of detective novels and short stories by Dorothy L. Sayers (and their continuation by Jill Paton Walsh). A dilettante who solves mysteries fo ...

, solve a case of murder by arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, ...

poisoning, and quotes the last line from Housman's poem.

*In ''The Grass Crown

''The Grass Crown'' is the second historical novel in Colleen McCullough's ''Masters of Rome'' series, published in 1991.

The novel opens shortly after the action of ''The First Man in Rome''. Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla eat dinner ...

'', the second in the ''Masters of Rome

''Masters of Rome'' is a series of historical novels by Australian author Colleen McCullough, set in ancient Rome during the last days of the old Roman Republic; it primarily chronicles the lives and careers of Gaius Marius, Lucius Cornelius Su ...

'' series, Colleen McCullough describes in detail the various aspects of his life – the murder of Laodice, and the Roman Consul who, quite alone and surrounded by the Pontic army, ordered Mithridates to leave Cappadocia immediately and go back to Pontus – which he did.

*''The Last King'' is a historical novel by Michael Curtis Ford about the King and his exploits against the Roman Republic.

*Mithridates is a major character in Poul Anderson

Poul William Anderson (November 25, 1926 – July 31, 2001) was an American fantasy and science fiction author who was active from the 1940s until the 21st century. Anderson wrote also historical novels. His awards include seven Hugo Awards and ...

's novel ''The Golden Slave.''

*In the novel ''Mithridates is Dead'' (Spanish''Mitrídates ha muerto''

, Ignasi Ribó traces parallels between the historical figures of Mithridates and Osama Bin Laden. Within a postmodern narrative of the making and unmaking of history, Ribó suggests that the

September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commer ...

on the United States closely paralleled the massacre of Roman citizens in 88 B.C. and prompted similar consequences, namely the imperialist overstretch of the American and Roman republics respectively. Furthermore, he suggests that the ensuing Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were three conflicts fought by Rome against the Kingdom of Pontus and its allies between 88 BC and 63 BC. They are named after Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus who initiated the hostilities after annexing the Roman provi ...

were one of the key factors in the demise of Rome's republican regime, as well as in the spread of the Christian faith in Asia Minor and eventually throughout the whole Roman Empire. The novel implies that the current events in the world might have similar unforeseen consequences.

*In ''The King's Gambit'', the first volume of the SPQR series

The ''SPQR'' series is a series of historical mystery stories by John Maddox Roberts, published between 1990 and 2010, and set in the final years of the Roman Republic. SPQR (the original title of the first book, until the sequels came out) is ...

by John Maddox Roberts

John Maddox Roberts is an American author of science fiction, fantasy, and historical fiction including the ''SPQR'' series and '' Hannibal's Children''.

Personal life

John Maddox Roberts was born in Ohio and was raised in Texas, California, a ...

, the protagonist, Decius Metellus, becomes aware of a plot between Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

and Crassus to relieve Lucullus of command and allow Pompey to lead the final campaign against Mithradates. At the time of this novel, Decius reflects that Mithradates has successfully resisted Roman military campaigns for so long that the public has built him up as some kind of superhuman bogeyman

The Bogeyman (; also spelled boogeyman, bogyman, bogieman, boogie monster, boogieman, or boogie woogie) is a type of mythic creature used by adults to frighten children into good behavior. Bogeymen have no specific appearance and conceptions var ...

.

*Mithridates and his wife Monime are characters in Steven Saylor

Steven Saylor (born March 23, 1956) is an American author of historical novels. He is a graduate of the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied history and classics.

Saylor's best-known work is his '' Roma Sub Rosa'' historical myster ...

's 2015 novel ''Wrath of the Furies''.

See also

*Bosporan Kingdom

The Bosporan Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus (, ''Vasíleio toú Kimmerikoú Vospórou''), was an ancient Greco-Scythian state located in eastern Crimea and the Taman Peninsula on the shores of the Cimmerian Bosporus, ...

* Mithridatism

Mithridatism is the practice of protecting oneself against a poison by gradually self-administering non-lethal amounts. The word is derived from Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus, who so feared being poisoned that he regularly ingested small dos ...

(Mithridatization)

* Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were three conflicts fought by Rome against the Kingdom of Pontus and its allies between 88 BC and 63 BC. They are named after Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus who initiated the hostilities after annexing the Roman provi ...

* '' Epistula Mithridatis''

* Roman Crimea The Crimean Peninsula (at the time known as ''Taurica'') was under partial control of the Roman Empire during the period of 47 BC to c. 340 AD.

The territory under Roman control mostly coincided with the Bosporan Kingdom (although under Nero, from ...

References

Sources

* * * *Further reading

* Duggan, Alfred, ''He Died Old: Mithradates Eupator, King of Pontus'', 1958. * Ford, Michael Curtis, ''The Last King: Rome's Greatest Enemy'', New York, Thomas Dunne Books, 2004, * McGing, B. C. ''The Foreign Policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus'' (''Mnemosyne'', Supplements: 89), Leiden, Brill Academic Publishers, 1986, aperback* Cohen, Getzel M., ''Hellenistic Settlements in Europe, the Islands and Asia Minor'' (Berkeley, 1995). * Ballesteros Pastor, Luis. ''Mitrídates Eupátor, rey del Ponto''. Granada: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Granada, 1996, . * Ribó, Ignasi''Mitrídates ha muerto''

Madrid, Bubok, 2010, * Mayor, Adrienne, ''The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy'' (Princeton, PUP, 2009). * Madsen, Jesper Majbom, Mithradates VI : Rome's perfect enemy. In: ''Proceedings of the Danish Institute in Athens'' Vol. 6, 2010, pp. 223–237. * Ballesteros Pastor, Luis, ''Pompeyo Trogo, Justino y Mitrídates. Comentario al'' Epítome de las Historias Filípicas ''(37,1,6–38,8,1)'' (''Spudasmata'' 154), Hildesheim-Zürich-New York, Georg Olms Verlag, 2013, .

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mithridates 06 Eupator 135 BC births 63 BC deaths 2nd-century BC Iranian people 1st-century BC Iranian people 1st-century BC rulers in Asia Achaemenid dynasty Ancient child rulers Ancient Pontic Greeks Deaths by blade weapons Iranian people of Greek descent Mithridatic Wars Mithridatic kings of Pontus Rulers of the Bosporan Kingdom