Military history of Australia during the Second Boer War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The military history of Australia during the Boer War is complex, and includes a period of history in which the six formerly autonomous British Australian colonies federated to become the

The military history of Australia during the Boer War is complex, and includes a period of history in which the six formerly autonomous British Australian colonies federated to become the

A Boer force of mostly farmer volunteers, formed up as mounted infantry, armed primarily with German built

A Boer force of mostly farmer volunteers, formed up as mounted infantry, armed primarily with German built

The Australian contribution consisted of five phases. The first was the contingents each government dispatched in response to the outbreak of the war. Although hostilities only commenced on 10 October 1899, the first squadron of New South Wales Lancers arrived in

The Australian contribution consisted of five phases. The first was the contingents each government dispatched in response to the outbreak of the war. Although hostilities only commenced on 10 October 1899, the first squadron of New South Wales Lancers arrived in

In the months prior to the departure of the first Federal Contingent, The 1st

In the months prior to the departure of the first Federal Contingent, The 1st

The beginning of 1900 saw the first Australian contingents deploying to the north of the Cape Colony. The new year begun much as the previous one had ended though, with the British suffering a further defeat at the

The beginning of 1900 saw the first Australian contingents deploying to the north of the Cape Colony. The new year begun much as the previous one had ended though, with the British suffering a further defeat at the

DFD = 'Died From Disease'

Australia and the Boer War, 1899–1902

– Australian War Memorial

The Boer War

– National Archives of Australia

The Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) An Australian Perspective

– The Australian Boer War Memorial

The Boer War

– Culture Portal

The Boer War: Army, Nation and Empire

– The Australian Army {{Australian Military History Second Boer War

The military history of Australia during the Boer War is complex, and includes a period of history in which the six formerly autonomous British Australian colonies federated to become the

The military history of Australia during the Boer War is complex, and includes a period of history in which the six formerly autonomous British Australian colonies federated to become the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. At the outbreak of the Second Boer War, each of these separate colonies maintained their own, independent military forces, but by the cessation of hostilities, these six armies had come under a centralised command to form the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), who ...

.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, an escalating conflict between the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

and the Boer republics of southern Africa, led to the outbreak of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

, which lasted from 11 October 1899, until 31 May 1902. In a show of support for the empire, the governments of the self-governing British colonies of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, Natal, Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

and the six Australian colonies all offered men to participate in the conflict. The Australian contingents, numbering over 16,000 men, were the largest contribution from the Empire, and a further 7,000 Australian men served with other colonial or irregular units. At least 60 Australian women also served in the conflict as nurses.R.L. Wallace, Australians at the Boer War, AGPS, Canberra, 1976.

Background

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

first gained control of the southern tip of Africa during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

. The Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

built the first Cape settlement in 1652, bringing southern Africa into the Dutch Empire. In 1795 revolutionary France

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

invaded and occupied the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

, and established a puppet allied-state there, known as the Batavian Republic

The Batavian Republic ( nl, Bataafse Republiek; french: République Batave) was the successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. It was proclaimed on 19 January 1795 and ended on 5 June 1806, with the accession of Louis Bon ...

. All the former colonies of the Dutch Republic came under the control of the Batavian Republic, who were allied to France, Britain's enemy in the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

.Thompson, L. The Unification of South Africa 1902–1910, Oxford University Press 1960

Realising the Cape's strategic importance for control of the seas and access to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

and the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

, Britain attacked the Batavian Republic's outpost at the Cape of Good Hope in the Battle of Muizenberg

The Invasion of the Cape Colony, also known as the Battle of Muizenberg, was a British military expedition launched in 1795 against the Dutch Cape Colony at the Cape of Good Hope. The Dutch colony at the Cape, established and controlled by the ...

. The British victory in the battle brought about the establishment of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

. Although it was briefly returned to the Batavian Republic in 1803 under the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

, a resumption of hostilities saw Britain again take control of the Cape Colony in 1806 following the Battle of Blaauwberg

The Battle of Blaauwberg, also known as the Battle of Cape Town, fought near Cape Town on Wednesday 8 January 1806, was a small but significant military engagement. After a British victory, peace was made under the Treaty Tree in Woodstock. ...

. This battle established permanent British rule over the Cape.

Unhappy with British rule, the Southern African Dutch, known as Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this a ...

, migrated further north, establishing the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

(Transvaal Republic), Natal, and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

.

British imperial and commercial interests increasingly impinged on the Boer republics, who resented British influence in their affairs. The majority of the territory of Natal was annexed by the British in 1843, and although the British government formally recognised the two remaining Boer republics in the 1850s, they then annexed the Transvaal in 1877. Tired of British aggression towards them, the Boers finally hit back, leading to the outbreak of the First Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

. Lasting from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881, the First Boer War was a humiliating reversal for the British, who suffered a disastrous loss at the Battle of Majuba Hill

The Battle of Majuba Hill on 27 February 1881 was the final and decisive battle of the First Boer War that was a resounding victory for the Boers. The British Major General Sir George Pomeroy Colley occupied the summit of the hill on the night ...

on 27 February 1881, and were compelled to sign the Pretoria Convention

The Pretoria Convention was the peace treaty that ended the First Boer War (16 December 1880 to 23 March 1881) between the Transvaal Boers and Great Britain. The treaty was signed in Pretoria on 3 August 1881, but was subject to ratification by ...

, which granted the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

under a nominal British suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

.

Just six years later in 1886, gold was discovered in the Republic, and a large influx of British prospectors

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by Mining engineering#Pre-mining, exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

...

(referred to as uitlanders

Uitlander, Afrikaans for "foreigner" (lit. "outlander"), was a foreign (mainly British) migrant worker during the Witwatersrand Gold Rush in the independent Transvaal Republic following the discovery of gold in 1886. The limited rights granted to ...

by the Boers) increasingly led to confrontation with the Boers. What began as an internal problem for the South African Republic soon became an international problem, as Britain sought to protect, and even extend the rights of its citizens within the South African Republic. Britain had been unhappy with the outcome of the First Boer War, and wished to restore influence over the Transvaal.

Under the pretext of negotiating uitlander rights, Britain sought to gain control over the gold and diamond mining industries, and demanded a franchising policy, which they knew would be unacceptable to the Boers. When the negotiations failed to come to an acceptable outcome, British foreign secretary Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

issued an ultimatum to the South African Republic. Realising that war was inevitable, President Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

gave Britain a 48-hour deadline to withdraw its troops from their borders. When Britain failed to comply, the South African Republic, along with their allies, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State declared war on Britain and set about launching pre-emptive strikes into British held territory.

Outbreak of hostilities

A Boer force of mostly farmer volunteers, formed up as mounted infantry, armed primarily with German built

A Boer force of mostly farmer volunteers, formed up as mounted infantry, armed primarily with German built Mauser

Mauser, originally Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik ("Royal Württemberg Rifle Factory"), was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols has been produced since the 1870s for the German arm ...

Model 1895 rifles. The effectiveness and superiority of this weapon over the British Lee–Metford

The Lee–Metford rifle (a.k.a. ''Magazine Lee–Metford'', abbreviated ''MLM'') was a bolt-action British army service rifle, combining James Paris Lee's rear-locking bolt system and detachable magazine with an innovative seven groove rifled b ...

and Lee–Enfield Mark I, led to the development of the Pattern 1913 Enfield, and the upgrading of the Lee–Enfield to the SMLE Mark III, which would be the stock rifle of choice for most British Empire armies in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. These highly mobile mounted infantry formed the basis of the Boer Commando

The Boer Commandos or "Kommandos" were volunteer military units of guerilla militia organized by the Boer people of South Africa. From this came the term "commando" into the English language during the Second Boer War of 1899-1902 as per Costica ...

, which was the primary organisational unit of the Boers.

At the outbreak of hostilities, a superior rifle was not the only advantage held by the Boers. The British forces in southern Africa were still composed mostly of infantry, while most of the Boers were skilled horsemen, who used their superior mobility to good advantage. Realising that continuing to engage the British in set-piece battles where British troops could utilize their superior numbers would result in a quick defeat, the Boers adopted tactics of hit-and-run guerilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ...

attacks, picking off men, and disrupting supply lines.Reitz, Deneys (1930). Commando: A Boer Journal of the Boer War. London: Faber and Faber.

The Boers first struck at the Battle of Kraaipan on 12 October 1899. Late at night, 800 commandos rode south into the Cape Colony, attacking the British garrison at Kraaipan and cutting railway and telegraph lines. Although the British repelled their advance at the Battle of Talana Hill

The Battle of Talana Hill, also known as the Battle of Glencoe, was the first major clash of the Second Boer War. A frontal attack by British infantry supported by artillery drove Boers from a hilltop position, but the British suffered heavy casu ...

, and the Battle of Elandslaagte

The Battle of Elandslaagte (21 October 1899) was a battle of the Second Boer War, and one of the few clear-cut tactical victories won by the British during the conflict. However, the British force retreated afterwards, throwing away their advan ...

, the Boers continued to pour south, besieging the British settlement of Ladysmith and advancing on Mafeking and Kimberley.

As the Boers established siege-guns around Ladysmith, the British commander of the garrison there, Sir George Stuart White, attempted a sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining supp ...

with cavalry against the Boer gun positions, but the attack was a disaster, and a state of siege followed as both side attempted to consolidate their position.

Arrival of the Australians

The involvement of men from the Australian colonies in the Second Boer War was complex. They included the official contingents dispatched by each of the six colonial governments, Australians who were already in southern Africa working as gold-miners enlisting in British or Cape Colony regiments such as theBushveldt Carbineers

The Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) were a short-lived, irregular mounted infantry regiment, raised in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

The 320-strong regiment was formed in February 1901 and commanded by an Australian, Colonel R. W. Leneha ...

, men who made their own way to participate, and others who joined privately raised units such as Doyle's Australian Scouts.Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (Third ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. After Australia federated to become the Commonwealth of Australia, the men of the six separate colonial contingents were reorganised into new Commonwealth contingents. Although in a minority, some Australians were anti-imperialists, and supported the Boer cause. Although their number is uncertain, it is known that some Australians, such as Arthur Alfred Lynch

Arthur Alfred Lynch (16 October 1861 – 25 March 1934) was an Irish Australian civil engineer, physician, journalist, author, soldier, anti-imperialist and polymath. He served as MP in the UK House of Commons as member of the Irish Parli ...

, participated in the conflict on the Boer side. Upon the outbreak of hostilities, the British government initially requested troops from New South Wales, which had previously provided the New South Wales Lancers

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

serving in the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

in Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

. Although they were armed with rifles, the NSW Lancers did go into action during the Boer War charging with their lances on more than one occasion.

As planning advanced, and the need for troop numbers increased, this request was soon forwarded to each of the colonies. The War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

devised a plan for two contingents of 125 men each from New South Wales and Victoria, and one contingent of 125 men each from Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

, Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, and Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

, to be attached to separate British units. The six colonial governments each held their own parliamentary debates about the support that would be offered. Although there were elements of opposition within each government, support was general and widespread in each colony.

Britain realised the value of troops from the Australian colonies. The climates and geography of Southern Africa and Australia were quite similar, and most Australian soldiers, the vast majority of whom were trained as mounted rifles

Mounted infantry were infantry who rode horses instead of marching. The original dragoons were essentially mounted infantry. According to the 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Mounted rifles are half cavalry, mounted infantry merely specially m ...

, were well-suited to operating in such terrain. Britain was also quick to understand the need for further horsemen, as the Boers operated with a high degree of mobility across the Southern African grasslands, often referred to romantically as 'the vastness of the veld

Veld ( or ), also spelled veldt, is a type of wide open rural landscape in :Southern Africa. Particularly, it is a flat area covered in grass or low scrub, especially in the countries of South Africa, Lesotho, Eswatini, Zimbabwe and Bot ...

t'. At that time, most British troops were recruited from within urban environments, and although their ability as soldiers was not questioned, they did not have the natural horsemanship

Natural horsemanship is a collective term for a variety of horse training techniques which have seen rapid growth in popularity since the 1980s. The techniques vary in their precise tenets but generally share principles of "a kinder and gentler ...

and bush craft of the Australians, many of whom came from rural backgrounds.

The Australian contribution consisted of five phases. The first was the contingents each government dispatched in response to the outbreak of the war. Although hostilities only commenced on 10 October 1899, the first squadron of New South Wales Lancers arrived in

The Australian contribution consisted of five phases. The first was the contingents each government dispatched in response to the outbreak of the war. Although hostilities only commenced on 10 October 1899, the first squadron of New South Wales Lancers arrived in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

on 2 November to join the British force assembled under the command of General Sir Redvers Henry Buller. The Lancers had been training in England at the time, and were quickly dispatched to southern Africa as soon as permission was received from the Government of New South Wales

The Government of New South Wales, also known as the NSW Government, is the States and territories of Australia, Australian state democratic administrative authority of New South Wales. It is currently held by a coalition of the Liberal Party o ...

.

By 22 November the Lancers were already conducting patrols, and were soon attacked near Belmont, where they forced their attackers to withdraw after inflicting serious casualties upon them. The NSW Lancers were again called into action at the Battle of Modder River

The Battle of Modder River ( af, Slag van die Twee Riviere, lit=Battle of the two rivers) was an engagement in the Boer War, fought at Modder River, on 28 November 1899. A British column under Lord Methuen, that was attempting to relieve the ...

, where along with Lord Methuen's British column, they attempted to relieve the siege of Kimberley. Although they forced the Boers to retreat, the British suffered heavy casualties in the attempt, and also had to withdraw, allowing the Boers to re-establish their trench lines.

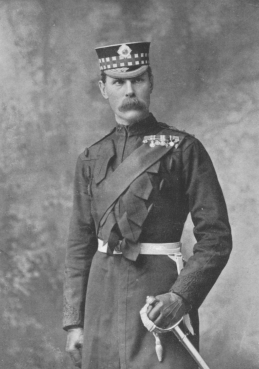

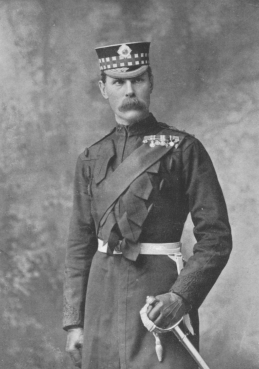

As they had less distance to travel, the Western Australian contingent, consisting solely of the 1st Western Australian Mounted Infantry arrived in mid-November, were the first to arrive directly from Australia, and were quickly dispatched for Natal. On 26 November, the first contingents of infantry from South Australia (1st South Australian Mounted Rifles), Tasmania (Tasmanian Mounted Infantry), Victoria (1st Victorian Mounted Rifles) and Western Australia arrived in Cape Town, and despite retaining their own independent commands, for logistical reasons they were designated as the '1st Australian Regiment', and came under overall command of Major-General Sir John Charles Hoad

Major General Sir John Charles Hoad (25 January 1856 – 6 October 1911) was an Australian military leader, best known as the Australian Army's second Chief of the General Staff.Warren Perry'Hoad, Sir John Charles (1856–1911)' Australian Dict ...

. The 1st Queensland Mounted Infantry had also arrived to join them by mid-December. Another mounted infantry unit from New South Wales, known as the 1st Australian Horse

The 1st Australian Horse was a mounted infantry regiment of the Colony of New South Wales that was formed in 1897. The 1st Australian Horse wore distinctive myrtle green uniforms with black embroidery.

History

Formation

The regiment was rais ...

, also arrived in December. Despite their name, they were raised purely from within the Colony of New South Wales, although this unit would go on to become the precursor of the first Australian Light Horse

Australian Light Horse were mounted troops with characteristics of both cavalry and mounted infantry, who served in the Second Boer War and World War I. During the inter-war years, a number of regiments were raised as part of Australia's part-t ...

unit. Hoad ordered the combined force to ride north towards the Orange River

The Orange River (from Afrikaans/Dutch: ''Oranjerivier'') is a river in Southern Africa. It is the longest river in South Africa. With a total length of , the Orange River Basin extends from Lesotho into South Africa and Namibia to the north ...

, where they were to link up with the Kimberley Relief Force under Lieutenant-General Lord Methuen.

Although they were in the Cape Colony at the time, no units from the Australian colonies were involved in the Black Week

Black Week refers to the week of 10–17 December 1899 during the Second Boer War, when the British Army suffered three devastating defeats by the Boer Republics at the battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso. In total, 2,776 British ...

between 10 and 17 December, in which Britain suffered three successive defeats at the Battle of Stormberg

The Battle of Stormberg was the first British defeat of Black Week, in which three successive British forces were defeated by Boer irregulars in the Second Boer War.

Background

When the British first drew up a plan of campaign against the Boer ...

, the Battle of Magersfontein

The Battle of MagersfonteinSpelt incorrectly in various English texts as "Majersfontein", "Maaghersfontein" and "Maagersfontein". ( ) was fought on 11 December 1899, at Magersfontein, near Kimberley, South Africa, on the borders of the Cape Co ...

, and the Battle of Colenso

The Battle of Colenso was the third and final battle fought during the Black Week of the Second Boer War. It was fought between British and Boer forces from the independent South African Republic and Orange Free State in and around Colenso, N ...

. The Boers knew that Empire forces would be sent to reinforce the British positions, and so sought to strike quickly against them.

By mid-December, the first two contingents of New South Wales Mounted Rifles (A Squadron and E Squadron), and the first contingent of Queensland Mounted Infantry (1st Queensland Mounted infantry) had both also arrived directly from Australia.

Aboriginal soldiers

Until recently it was thought that approximately 50 Aboriginal trackers went to South Africa to serve with the British forces against the Boers during the Boer War (1899–1902), after being personally requested by Lord Kitchener. The role that they supposedly played during the war was described in an article 'The Black Trackers of Bloemfontein' in Land Rights magazine (1990) by Indigenous historian David Huggonson. Several historians, including Dr Dale Kerwin, an Indigenous research fellow atGriffith University

Griffith University is a public research university in South East Queensland on the east coast of Australia. Formally founded in 1971, Griffith opened its doors in 1975, introducing Australia's first degrees in environmental science and Asian ...

, determined that the lack of surviving information about these Aboriginal trackers was partially due to the uncertainty around whether they had managed to return to Australia. Dr Kerwin claimed that a group of fifty black trackers may not have been allowed to return to Australia at the end of the war in 1902 due to the White Australia Policy

The White Australia policy is a term encapsulating a set of historical policies that aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin, especially Asians (primarily Chinese) and Pacific Islanders, from immigrating to Australia, starting i ...

.

According to extensive research by independent scholar, Peter Bakker (Melbourne), the ‘fifty black trackers’ story is a myth that arose from the misinterpretation of a few scant historical documents. Bakker's research arguably debunks the ‘fifty black trackers’ claim and challenges the entire narrative regarding Aboriginal participation in the Boer War. His research has led to the recognition of several Aboriginal men who saw service as regular privates or troopers who earned their place in their units on the basis of being capable horsemen, good shots with a rifle and their hardy bushcraft skills. Of the ten identified men of Aboriginal descent who had served in the Boer War (as of 2020) Bakker found that only one did not return to Australia. Contrary to prevailing narrative of former researchers, Bakker also found that none of the identified men served as trackers for their units or were from Queensland; where historians predicted most of the Aboriginal participants in the war to have originated.  In the months prior to the departure of the first Federal Contingent, The 1st

In the months prior to the departure of the first Federal Contingent, The 1st Australian Commonwealth Horse

The Australian Commonwealth Horse (ACH) was a mounted infantry unit of the Australian Army formed for service during the Second Boer War in South Africa in 1902 and was the first expeditionary military unit established by the newly formed Common ...

, on the 18 February 1902, a short article titled "The Melbourne Enrolment" appeared in The Queenslander on 25 January 1902, stating that: "the number of men so far attested for the Federal Contingent is 212. Two black trackers. Davis and F. King, have been taken on the strength". On 18 February 1902 a photograph appeared in the Town and Country Journal, which included a photograph of a man labelled "F King Black Tracker". According to Bakker's research, there is no evidence that Davis or F. King departed with this unit for overseas service but another Aboriginal man did: Jack Alick Bond. Jack's image can be seen numbered as 67 in a group photograph directly above that of F. King on the same page in the Australian Town and Country Journal

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Aus ...

.

A Yuin Aboriginal man, Jack Alick Bond, from Krawarree, New South Wales, has the unique distinction of not only having served in two tours of active duty in the Boer War but also receiving his Queen's South Africa medal in person from the Duke of Cornwall and York during the Royal Visit to Sydney on 30 May 1901. Jack Alick Bond had worked as a police tracker prior to enlisting as Trooper 1063 in a New South Wales colonial unit, the First Australian Horse, in 1900. Jack re-enlisted for a second tour as Trooper 356 in the First 1st Australian Commonwealth Horse

The Australian Commonwealth Horse (ACH) was a mounted infantry unit of the Australian Army formed for service during the Second Boer War in South Africa in 1902 and was the first expeditionary military unit established by the newly formed Common ...

in January 1902. Other men of Aboriginal descent that served in Boer War include Robert Charles Searle (Western Australia), William Charles Westbury (South Australia), Arthur Wellington (Victoria) and William Stubbings (New South Wales).

Counter-offensives

The beginning of 1900 saw the first Australian contingents deploying to the north of the Cape Colony. The new year begun much as the previous one had ended though, with the British suffering a further defeat at the

The beginning of 1900 saw the first Australian contingents deploying to the north of the Cape Colony. The new year begun much as the previous one had ended though, with the British suffering a further defeat at the Battle of Spion Kop

The Battle of Spioen Kop ( nl, Slag bij Spionkop; af, Slag van Spioenkop) was a military engagement between British forces and two Boer Republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, during the campaign by the British to ...

on 23 and 24 January, adding to the set-backs of Black Week. Despite the defeat at Spion Kop, reinforcements were flooding in from both Britain and the Empire. The 1st New South Wales Mounted Rifles, 'A' Field Battery of the NSW Artillery, the NSW Medical Team, and the 2nd Victorian Mounted Rifles all arrived in February, and the 2nd Queensland Mounted Infantry arrived in March. These Australian units joined the British forces being assembled by Lord Roberts, who had replaced General Buller in January, following concerns over his leadership through the bleak losses of the previous December.

Lord Roberts was placed in command of a five-division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

strong force of reinforcements sent to launch a counter-invasion of the Orange Free State. By mid-February his force amounted to over 180,000 men, the largest British expeditionary force deployed on overseas operations up to that date. His original plan had involved his column conducting an offensive north along the railway from Cape Town to Bloemfontein, and onto Pretoria. When they progressed north, they discovered the beleaguered forces under siege at Ladysmith and Kimberley. Upon discovering the nature of the situation with the sieges, Roberts broke his force up into several detachments to deal with each of the sieges. One force was commanded by Lieutenant-General John French, and consisted primarily of cavalry. French's detachment also included the New South Wales Lancers, Queensland Mounted Infantry, and New South Wales Army Medical Corps.

The British victory at Modder River had finally permitted the relief of Kimberley, and the retreating Boers were chased down and again engaged at the Battle of Paardeberg

The Battle of Paardeberg or Perdeberg ("Horse Mountain") was a major battle during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was fought near ''Paardeberg Drift'' on the banks of the Modder River in the Orange Free State near Kimberley.

Lord Methuen adv ...

which took place between 18 and 27 February 1900. The New South Wales Mounted Rifles and 1st Queensland Mounted Infantry both took part in this engagement, with the NSW Rifles managing to capture the Boer General Piet Cronjé. His capture caused a massive blow to Boer morale over the rest of the conflict. The British column broke the siege of Ladysmith

The siege of Ladysmith was a protracted engagement in the Second Boer War, taking place between 2 November 1899 and 28 February 1900 at Ladysmith, Natal.

Background

As war with the Boer republics appeared likely in June 1899, the War Offic ...

on 28 February, and entered Bloemfontein

Bloemfontein, ( ; , "fountain of flowers") also known as Bloem, is one of South Africa's three capital cities and the capital of the Free State province. It serves as the country's judicial capital, along with legislative capital Cape To ...

on 13 March. Despite suffering heavy casualties from both battle and disease, the British continued to drive on towards Pretoria

Pretoria () is South Africa's administrative capital, serving as the seat of the executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to South Africa.

Pretoria straddles the Apies River and extends eastward into the foothi ...

.

The second wave of units from the Australian colonies began to arrive in April. This wave consisted primarily of the ''Bushmen contingents''. The men for these newly raised units were recruited from a wide range of locales and had been primarily funded through either public subscription, or the donations of wealthy citizens who wished to be seen as contributing to the war effort. These units were again mounted infantry, and consisted of men with a natural skill at horsemanship, riflery and bushcraft

Bushcraft is the use and practice of skills, thereby acquiring and developing knowledge and understanding, in order to survive and thrive in a natural environment.

Bushcraft skills provide for the basic physiological necessities for human li ...

who were thought to be able to counter the skills of the Boer Commandoes. The 1st Bushmen Contingent (NSW), Queensland Citizen Bushmen

The Queensland Citizen Bushmen, also known as the 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry, was a mounted infantry regiment raised in Queensland for service during the Second Boer War. Formed as part of the third Queensland contingent with an original ...

, South Australian Citizen Bushmen, Tasmanian Citizen Bushmen, Victorian Citizen Bushmen, and Western Australian Citizen Bushmen all landed and headed towards Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

in April.

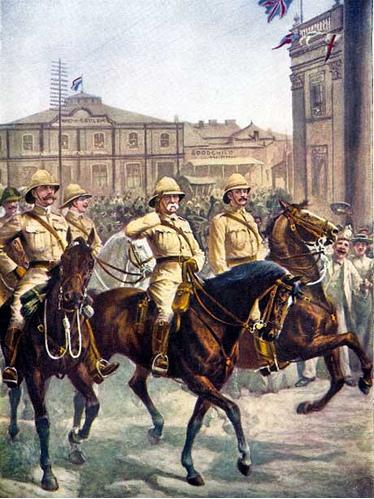

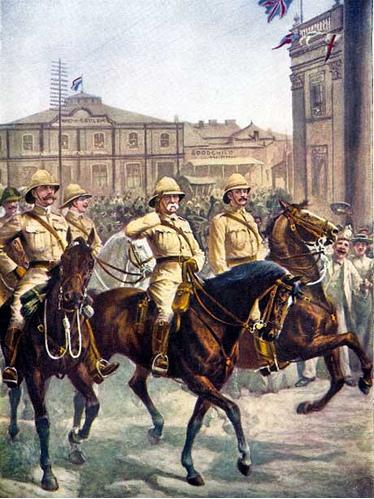

By May, the Australian contingents numbered over 3,000, and they were involved in the thick of the fighting, including the action at Driefontein

Driefontein is the Driefontein Mine in the West Witwatersrand Basin (West Wits) mining field. The West Wits field was discovered in 1931 and commenced operations with Venterspost Gold Mine in 1939. In 1952, the West Driefontein mine is opened. I ...

, and the Relief of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mafikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son of ...

on 17 May, which provoked wild celebrations on the streets of London. The third contingents from the Australian colonies had also begun to arrive in southern Africa. These were ‘Imperial Bushmen’ units, which were identical in composition, recruitment and structure as the preceding ‘bushmen’ units, except that they had been funded by the Imperial government in London as opposed to local subscription and donation. The British government had been so impressed by the performance of the Australian units that they had decided to fund the raising of additional units.

An outbreak of typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

badly affected the British and Empire forces, but they were soon able to resume their campaign. Roberts’ column was again halted briefly at Kroonstad due to problems with supplies, but after 10 days they continued the push towards Johannesburg. On 28 May The Orange Free State was formally annexed, and renamed as the Orange River Colony. By 30 May, Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a Megacity#List of megacities, megacity, and is List of urban areas by p ...

had also fallen into the hands of Lord Roberts’ force, and four days later the Boers were retreating from Pretoria. Men from all of the Australian units were in some way involved in the taking of Johannesburg.

Pretoria, the capital of Transvaal Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

fell into British hands on 5 June. The first men into Pretoria, were the New South Wales Mounted Rifles, whose commander, Lt. William Watson persuaded the Boers to surrender the capital.

Heavy fighting soon again broke out in the Battle of Diamond Hill

The Battle of Diamond Hill (Donkerhoek) () was an engagement of the Second Boer War that took place on 11 and 12 June 1900 in central Transvaal.

Background

The Boer forces retreated to the east by the time the capital of the South African ...

on 11 and 12 June, fought to prevent the Boer reinforcements from recapturing Pretoria. Men from each of the Australian contingents, most notable the New South Wales, and Western Australian Mounted Rifles all took part in this battle, which was seen as a victory by both sides. Lord Roberts was pleased to have forced the Boers to retreat from Pretoria, but the forces of Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer Wa ...

had inflicted heavy casualties on the British forces.

Orange Free State President Martinus Theunis Steyn

Martinus (or Marthinus) Theunis Steyn (; 2 October 1857 – 28 November 1916) was a South African lawyer, politician, and statesman. He was the sixth and last president of the independent republic the Orange Free State from 1896 to 1902.

Earl ...

, and President Paul Kruger

Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger (; 10 October 1825 – 14 July 1904) was a South African politician. He was one of the dominant political and military figures in 19th-century South Africa, and President of the South African Republic (or ...

of the South African Republic, had both retreated with surviving elements of their governments, into eastern Transvaal. Roberts was determined to capture the rebel presidents to end any opposition to British rule. He joined up with Buller's remaining forced from Natal, and advanced into the eastern Transvaal against them.

The British met a 5,000 strong Boer force under General Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer Wa ...

at the Battle of Bergendal

The Battle of Berg-en-dal (also known as the Battle of Belfast or Battle of Dalmanutha) took place in South Africa during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

The battle was the last set-piece battle of the war, although the war was still to last another t ...

which lasted from 21 to 27 August, and would prove to be the last set-piece battle of the war. Despite fierce resistance, the Boers were overwhelmed by the 20,000 strong British force. The broken Boers retreated from the field, and the next day, 28 August, the British marched into Machadodorp

Machadodorp, also known by its official name eNtokozweni, is a small town situated on the N4 road, near the edge of the escarpment in the Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The Elands River runs through the town. There is a natural radioactive ...

, hoping to capture the Boer presidents. They had already left for Nelspruit

Mbombela (also known as Nelspruit) is a city in northeastern South Africa. It is the capital of the Mpumalanga province. Located on the Crocodile River, Mbombela lies about by road west of the Mozambique border, east of Johannesburg and north ...

, where the temporarily established their governments. With the British still in pursuit, Kruger and his former Transvaal government ministers were nearly cornered. However, the Queen of the Netherlands felt a high degree of sympathy towards the Boers, and offered Kruger a means of escape. Ignoring a Royal Navy blockade, 20-year-old Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands

Wilhelmina (; Wilhelmina Helena Pauline Maria; 31 August 1880 – 28 November 1962) was Queen of the Netherlands from 1890 until her abdication in 1948. She reigned for nearly 58 years, longer than any other Dutch monarch. Her reign saw World Wa ...

sent the Dutch warship '' De Gelderland'' to their rescue. Kruger escaped to live in exile in Switzerland, but died there in 1904.Neil G. Speed, Born to Fight, Caps & Flints Press, Melbourne, 2002. (an Australian Maj. Charles Ross DSO who served with Canadian Scouts)

The Battle of Bergendal had forced the Boers to abandon their hopes of achieving an outcome through direct, military confrontation of the enemy. But despite their defeats much of the Boer army remained intact, and Botha dispersed his men to Lydenburg

Lydenburg, officially known as Mashishing, is a town in Thaba Chweu Local Municipality, on the Mpumalanga highveld, South Africa. It is situated on the Sterkspruit/Dorps River tributary of the Lepelle River at the summit of the Long Tom Pass. ...

and Barberton to begin a new phase of the conflict.

With all of the major population centres under British control, Roberts declared the war to be over on 3 September 1900, and formally annexed the South African Republic, declaring all formerly Boer territory to be under British control.

Guerrilla warfare phases

The loss of the capitals did not deter the Boers. Instead, they moved their campaign into a phase ofguerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

, in which Boer commandos operating in small groups, picked off men through sniping, disrupted troop movements and supply lines, and launched ambush attacks on individual or isolated units, or launched larger-scale raids against important targets.

Realising the campaign had been progressing well for the British, the Boer commanders had earlier met in secret in Kroonstad, and planned out their guerrilla campaign against British supply and communication lines. The first major attack of this new phase was the attack at Sanna's Post on 31 March 1900, in which Boer commander Christiaan de Wet led a force of 2,000 commandos from the former Orange Free State in a major attack on Bloemfontein's waterworks system 23 miles (37 km) east of the city. In the same attack they also ambushed a British convoy killing 155 British soldiers, and capturing seven guns, 117 wagons and 428 prisoners.

To sustain their guerrilla campaign, the Boers needed a regular supply of food, ammunition and equipment. In an effort to obtain such supplies, Koos de la Rey

Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey (22 October 1847 – 15 September 1914), better known as Koos de la Rey, was a South African military officer who served as a Boer general during the Second Boer War. also had a political career and was one of the ...

led a 3,000 strong Boer attack on the British post at Brakfontein on the Elands River in Western Transvaal on 4 August 1900. At the time, it was lightly defended by 300 Australians, comprising 105 New South Wales Citizens' Bushmen, 141 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry, 2 Tasmanian Bushmen, 42 Victorian Bushmen, and 9 West Australian Bushmen, as well as an additional 201 Rhodesian Volunteers. De le Rey's force surrounded the outpost, but magnanimously offered to deliver the Australians to the nearest British position unharmed if they surrendered the supplies they were guarding. The commanding officer of the camp, Colonel Charles Hore, refused the offer. The Boers bombarded the Australian position with artillery fire. In two days they fired over 2,500 shells at the Elands River outpost. The defenders suffered 32 casualties, but continued to repulse any attempt to seize the outpost. The Boers turned back a relief force sent to assist the Australians, but were unable to take the position itself. After 11 days without success, and with the prospect of further reinforcements arriving, the Boers broke their siege and withdrew. The Australians and Rhodesians had successfully defended the Elands River outpost, and were eventually relieved on 16 August. The Boer commander, Koos de la Rey, was quoted as saying:

In response to the Boers desperate need of supplies, the British command changed tactics, adopting a counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

approach. They established heavily defended blockhouses along supply-lines, and used a scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, commun ...

policy, burning houses and crops, and interning Boers in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

. This caused the costs of the campaign to rise dramatically, and began to have a negative impact on the popularity of the campaign amongst ordinary Australians. Some even started to feel sympathy for the Boers.

Formation of the Commonwealth

TheCommonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

came into existence on 1 January 1901 as a result of the federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

of the Australian colonies, and defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense indus ...

was made a responsibility of the new centralised, federal government. This brought about the creation of the Department of Defence Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philippin ...

, and two months later on 1 March 1901, the formation of the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), who ...

.

All existing military units of each of the six colonies were transferred into the Australian Army, which at the time of formation consisted of 28,923 colonial soldiers, including 1,457 professional soldiers, 18,603 paid militia and 8,863 unpaid volunteers, including those on active service in South Africa. For practical reasons, and so as not to disrupt the ongoing war effort in South Africa, individual units continued to be administered under the various colonial Acts until the Defence Act 1903 brought all of the units under one piece of legislation.

In reality the only clear indication of the Australian men's new allegiance to the Commonwealth, was in the form of hat-badge changing ceremonies that took place in the field. The colonial troop's original badges of their home colony were replaced with Rising Sun Badges, the symbol of the newly formed Australian Army. It was also not practical or economical for the men to adopt a single uniform, or standardise equipment, and so each colonial unit continued to utilise their original uniforms and equipment.

After Federation in 1901, eight Australian Commonwealth Horse

The Australian Commonwealth Horse (ACH) was a mounted infantry unit of the Australian Army formed for service during the Second Boer War in South Africa in 1902 and was the first expeditionary military unit established by the newly formed Common ...

battalions of the newly created Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), who ...

were also sent to South Africa, although they saw little fighting before the war ended.Odgers 1994, p. 32. Some Australians later joined local South African irregular units, instead of returning home after discharge. These soldiers were part of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

, and were subject to British military discipline. Such units included the Bushveldt Carbineers

The Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) were a short-lived, irregular mounted infantry regiment, raised in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

The 320-strong regiment was formed in February 1901 and commanded by an Australian, Colonel R. W. Leneha ...

which gained notoriety as the unit in which Harry "Breaker" Morant and Peter Handcock served in before their - to this day controversial and contested legitimate - court martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

under the British military code of the day, and their subsequent further controversial execution for what has been labelled the first war crimesOdgers 1994, p. 48. tribunal by some historians.

Closing stages

By the beginning of 1901, British forces were in control of almost all Boer territory, with the exception of some zones in northern Transvaal. While the Boers continued to conduct raids against British infrastructure and supply lines, their ability to disrupt British operations, or launch significant attacks had been totally reduced. Boers returned to their local districts in the hope that locals that knew them would offer sustenance and support. Although the Boers continued to hit back when they could, once the armies were dispersed their effectiveness diminished greatly. By mid-1901, the bulk of the fighting was over, and British mounted units would ride at night to attack Boer farmhouses or encampments, overwhelming them with superior numbers. Indicative of warfare in last months of 1901, the New South Wales Mounted Rifles traveled 1,814 miles (2,919 km) and were involved in thirteen skirmishes, killing 27 Boers, wounding 15, and capturing 196 for the loss of 5 dead and 19 wounded. Other notable Australian actions included Sunnyside, Slingersfontein, Pink Hill, Rhenosterkop and Haartebeestefontein. By 1902, British and colonial forces were concentrating on denying remaining Boers the ability to move their forces across Southern Africa. The scorched-earth tactics implemented by Lord Kitchener were by this point beginning to starve the Boers into submission. The British began to utilise "sweeper columns", consisting ofmounted infantry

Mounted infantry were infantry who rode horses instead of marching. The original dragoons were essentially mounted infantry. According to the 1911 ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Mounted rifles are half cavalry, mounted infantry merely speciall ...

, which ranged across entire districts scouring them for Boer guerillas, suspected or otherwise.

The British policy of containment and dispersal had been highly effective, and by March 1902, all significant opposition from the Boers had ended. In March, the British offered peace terms, but these were rejected by Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer Wa ...

. Suffering from disease and starvation, the last of the Boers surrendered in May, and on 31 May 1902, thirty delegates from the former South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

and Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

met British officials in Vereeniging

Vereeniging () is a town located in the south of Gauteng province, South Africa, situated where the Klip River empties into the northern loop of the Vaal River. It is also one of the constituent parts of the Vaal Triangle region and was formerly s ...

to discuss terms. Out of the negotiations Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

and Lord Kitchener produced the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided f ...

(also known as the Peace of Vereeniging), in which the Boer republics agreed to end hostilities, surrender their independence, and swear allegiance to the crown. In exchange, a general amnesty would be granted, no death penalties would be administered, and Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

would be permitted in schools and courts.

Although a brief period of self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

as British dominions followed, Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

, Colony of Natal

The Colony of Natal was a British colony in south-eastern Africa. It was proclaimed a British colony on 4 May 1843 after the British government had annexed the Boer Natalia Republic, Republic of Natalia, and on 31 May 1910 combined with three o ...

, Orange River Colony

The Orange River Colony was the British colony created after Britain first occupied (1900) and then annexed (1902) the independent Orange Free State in the Second Boer War. The colony ceased to exist in 1910, when it was absorbed into the Union ...

, and Transvaal were soon abolished by the South Africa Act 1909

The South Africa Act 1909 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which created the Union of South Africa from the British Cape Colony, Colony of Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal Colony. The Act also made provisions for ...

, which created a new British dominion over the whole of southern Africa, known as the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

.

Conclusion

Troops from the Australian colonies were widely considered to be very effective on the British side, well able to match the Boers tactics of high mobility warfare due to similar upbringings and working lives. Australians were not always successful however, suffering a number of heavy losses late in the war. On 12 June 1901, the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles lost 19 killed and 42 wounded at Wilmansrust, near Middleburg after poor security allowed a force of 150 Boers to surprise them. Three of the Australians were subsequently court-martialled for inciting mutiny.Odgers 1994, p. 47. On 30 October 1901, Victorians of the Scottish Horse Regiment also suffered heavy casualties at Gun Hill, although 60 Boers were also killed in the engagement. Meanwhile, at Onverwacht on 4 January 1902, the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen lost 13 killed and 17 wounded in the Battle of Onverwacht. Ultimately the Boers were defeated however, and the war ended on 31 May 1902. In all 16,175 Australians served in South Africa, and perhaps another 10,000 enlisted as individuals in Imperial units; casualties included 251 killed in action, 267 died of disease and 43 missing in action, while a further 735 were wounded. The war had the third largest number of fatalities in Australia's military history, behind only the world wars. In all likelihood, the total number of men from the Australian colonies to have served in the Second Boer War is probably between 20,000 and 25,000, making it the second largest contingent behind British troops. Five Australians were awarded theVictoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

. These were Neville Howse of the New South Wales Army Medical Corps; Trooper John Hutton Bisdee of the Tasmanian Imperial Bushmen; Lieutenant Guy Wylly of the Tasmanian Imperial Bushmen; Lieutenant Frederick William Bell of the West Australian Mounted Infantry; and Lieutenant Leslie Cecil Maygar

Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Cecil Maygar, (27 May 1868 – 1 November 1917) was an Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He was ...

of the 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles.Grebert, R. Australian Victoria Cross Recipients

Australian units involved in the Boer War

KIA = 'Killed in action'DFD = 'Died From Disease'

New South Wales

Queensland

South Australia

Tasmania

Victoria

Western Australia

Commonwealth of Australia

Australians also fought in the following units which were either privately raised or were raised in South Africa, but were not official units of the Australian colonies, or of the Commonwealth of Australia: * Australian Regiment * Australian Mounted Infantry Brigade * Australian Commonwealth Regiment *Bushveldt Carbineers

The Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) were a short-lived, irregular mounted infantry regiment, raised in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

The 320-strong regiment was formed in February 1901 and commanded by an Australian, Colonel R. W. Leneha ...

* Canadian Scouts

* 3rd Bushmen Regiment

* 4th Imperial Bushmen

* Composite Bushmen Regiment

* Cameron’s Scouts

* Doyle’s Australian Scouts

* Hasler’s Scouts

Timeline of the Australian contribution to the Second Boer War

See also

*Military history of Australia

The military history of Australia spans the nation's 230-year modern history, from the early Australian frontier wars between Aboriginals and Europeans to the ongoing conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 21st century. Although this h ...

* Australian Army battle honours of the Second Boer War

Notes

References

* Bufton, (1905). ''Tasmanians in the Transvaal War''. * Dennis, Peter; et al. (1995). ''The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History''. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. . * Dennis, Peter; et al. (2008). ''The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History'' (Second ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand. . * Festburg, Alfred S. and Barry J. Videon (1971). ''Uniforms of the Australian Colonies''. Hill of Content Publishing: Melbourne. * Field, L.M. (1979). ''The Forgotten War: Australian Involvement in the South African Conflict of 1899–1902''. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. * Grebert, R. (1990). ''Australian Victoria Cross Recipients''. * Grey, Jeffrey (1999). ''A Military History of Australia'' (Second ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. . * Grey, Jeffrey (2008). ''A Military History of Australia'' (Third ed.). Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. . * * Odgers, George (1994). ''100 Years of Australians at War''. Sydney: Lansdowne. . * Reay, WT (1901). ''Australians in War: With the Australian Regiment from Melbourne to Bloemfontein''. Melbourne: Massina. * Speed, Neil G. (2002). ''Born to Fight''. Caps & Flints Press, Melbourne. (an Australian Maj. Charles Ross DSO who served with Canadian Scouts) . * Thompson, L. (1960). ''The Unification of South Africa 1902–1910'', Oxford University Press. * Wallace, Robert (1912). ''The Australians at the Boer War''. Melbourne: Australian Government Printers. * Wilcox, Craig (2002). ''Australia's Boer War. The War in South Africa 1899–1902''. Oxford University Press. .Further reading

*External links

Australia and the Boer War, 1899–1902

– Australian War Memorial

– National Archives of Australia

– The Australian Boer War Memorial

The Boer War

– Culture Portal

The Boer War: Army, Nation and Empire

– The Australian Army {{Australian Military History Second Boer War