Military career of L. Ron Hubbard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The military career of L. Ron Hubbard saw the future founder of Scientology serving in the United States Armed Forces as a member of the Marine Corps Reserve and, between 1941–50, the Navy Reserve. He saw active service between 1941–45, during

Hubbard joined the

Hubbard joined the

Hubbard was posted to the Office of the Cable Censor in

Hubbard was posted to the Office of the Cable Censor in

When Hubbard arrived in Portland, USS ''PC-815'' was in the last stages of its construction. The ship, a steel-hulled subchaser of the ''PC-461'' class, had been laid down on October 10, 1942, at the Albina shipworks. She was commissioned on April 21, 1943, with Hubbard in command and Lt (jg) Thomas Moulton, an officer with whom he had studied in Florida, as the ship's

When Hubbard arrived in Portland, USS ''PC-815'' was in the last stages of its construction. The ship, a steel-hulled subchaser of the ''PC-461'' class, had been laid down on October 10, 1942, at the Albina shipworks. She was commissioned on April 21, 1943, with Hubbard in command and Lt (jg) Thomas Moulton, an officer with whom he had studied in Florida, as the ship's  Hubbard nonetheless continued to claim that he had sunk at least one Japanese submarine. Years later, in 1956, he told Scientologists:

In another lecture, he commented:

After the war, the

Hubbard nonetheless continued to claim that he had sunk at least one Japanese submarine. Years later, in 1956, he told Scientologists:

In another lecture, he commented:

After the war, the  Following its return to Astoria, USS ''PC-815'' was ordered to escort a new aircraft carrier to San Diego, where the subchaser was to participate in exercises. Miller, p. 138 On June 28, 1943, Hubbard ordered his crew to fire four shells from the ship's 3-inch gun and a number of rifle and pistol shots in the direction of the Coronado Islands, off which the ship anchored for the night. He did not realize that the islands belonged to

Following its return to Astoria, USS ''PC-815'' was ordered to escort a new aircraft carrier to San Diego, where the subchaser was to participate in exercises. Miller, p. 138 On June 28, 1943, Hubbard ordered his crew to fire four shells from the ship's 3-inch gun and a number of rifle and pistol shots in the direction of the Coronado Islands, off which the ship anchored for the night. He did not realize that the islands belonged to

On the same day that Hubbard was sent a formal letter of admonition, he reported sick with complaints of epigastric pains and possible

On the same day that Hubbard was sent a formal letter of admonition, he reported sick with complaints of epigastric pains and possible

Hubbard's military career has attracted comment from a number of journalists and writers over the years. The claims made by the Church of Scientology were not challenged by some early writers; C.H. Rolph quoted without comment a 1968 Scientology biographical sketch circulated to British

Hubbard's military career has attracted comment from a number of journalists and writers over the years. The claims made by the Church of Scientology were not challenged by some early writers; C.H. Rolph quoted without comment a 1968 Scientology biographical sketch circulated to British

Re B & G (Minors)

985' Family Law Reports 134 and 493. Retrieved 2009-07-14. Hubbard's military service has subsequently been covered in detail by the British writers

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, as a naval Lieutenant (junior grade)

Lieutenant junior grade is a junior commissioned officer rank used in a number of navies.

United States

Lieutenant (junior grade), commonly abbreviated as LTJG or, historically, Lt. (j.g.) (as well as variants of both abbreviations), is ...

and later as a Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

. After the war he was mustered out of active service and resigned his commission in 1950.

As with many other aspects of L. Ron Hubbard

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (March 13, 1911 – January 24, 1986) was an American author, primarily of science fiction and fantasy stories, who is best known for having founded the Church of Scientology. In 1950, Hubbard authored '' Dianetic ...

's life, accounts of his military career are much disputed. Streeter, pp. 207–208 His account of his military service later formed a major element of his public persona, as depicted by his Scientologist followers. Atack, p. 70 The Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is a group of interconnected corporate entities and other organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, which is variously defined as a cult, a scientology as a business, bu ...

presents Hubbard as a "much-decorated war hero who commanded a corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

and during hostilities was crippled and wounded".Lamont Lamont or LaMont may refer to:

People

*Lamont (name), people with the surname or given name ''Lamont'' or ''LaMont''

* Clan Lamont, a Scottish clan

Places Canada

*Lamont, Alberta, a town in Canada

* Lamont County, a municipal district in Albert ...

, pp. 19–20 According to Scientology publications, he served as a "Commodore of Corvette squadrons" in "all five theaters of World War II" and was awarded "twenty-one medals and palms" for his service.Rolph

Rolph is a surname and a masculine given name, and may refer to:

Surname

* C. H. Rolph, pen-name of C. R. Hewitt (1901–1994), English police officer, journalist, editor, and author

* Ebony Rolph (born 1994), Australian basketball player

* Gary R ...

, p. 16 He was "severely wounded and was taken crippled and blinded" to a military hospital, where he "worked his way back to fitness, strength and full perception in less than two years, using only what he knew and could determine about Man and his relationship to the universe."

However, his official Navy service records indicate that "his military performance was, at times, substandard", that he was only awarded a handful of campaign medals and that he was never injured or wounded in combat and was never awarded a Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, w ...

. Most of his military service was spent ashore in the continental United States on administrative or training duties. He briefly commanded two anti-submarine vessels, and , in coastal waters off Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

and California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in 1942 and 1943 respectively. He was removed from command of both vessels and rated by his superiors as being unsuitable for independent duties and "lacking in the essential qualities of judgment, leadership and cooperation". Although Hubbard asserted that he had attacked and crippled or sunk two Japanese submarines off Oregon while in command of USS ''PC-815'', his claim was rejected by the commander of the Northwest Sea Frontier

Sea Frontiers were several, now disestablished, commands of the United States Navy as areas of defense against enemy vessels, especially submarines, along the U.S. coasts. They existed from 1 July 1941 until in some cases the 1970s. Sea Frontiers ...

after a subsequent investigation. He was hospitalized for the last seven months of his active service, not with injuries but with an acute duodenal ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines ...

.

The Church of Scientology rejects the official record and insists that Hubbard had a ''second'' set of records that the U.S. Navy has concealed. According to the Church's chief spokesman, if it was true that Hubbard had not been injured, "the injuries that he handled by the use of Dianetics procedures were never handled, because they were injuries that never existed; therefore, Dianetics is based on a lie; therefore, Scientology is based on a lie."

Montana Army National Guard and US Marine Corps Reserve

Hubbard's first military service was with theMontana Army National Guard

The Montana Army National Guard is a component of the United States Army and the United States National Guard. Nationwide, the Army National Guard comprises approximately one half of the US Army's available combat forces and approximately one t ...

, which he joined at the age of 16 in October 1927 while still at school, falsely stating that his age was 18. Enlisting at the State Armory in his home town of Helena, Montana

Helena (; ) is the capital city of Montana, United States, and the county seat of Lewis and Clark County.

Helena was founded as a gold camp during the Montana gold rush, and established on October 30, 1864. Due to the gold rush, Helena would ...

, he served as a private in the Headquarters Company of 163rd Infantry. In May 1930, at the age of 19, he joined the Marine Corps Reserve 20th Regiment, a training unit connected with George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, preside ...

, where he was a student from 1930–32.

Hubbard attributed his service in the regiment to his need for "a little recreation. Life was dull. Fellow came up to me and he says, 'The Marine Reserves are organizing a twentieth regiment. Why don't you come down?'" He made the dubious claim of being rapidly promoted to the rank of First Sergeant; Hubbard later explained his unusually rapid promotion as being due to his unit being newly formed and his superiors being unable to "find anyone else who could drill". He stated that he was rated 'excellent' for military efficiency, obedience and sobriety. On October 22, 1931, Hubbard received an honorable discharge

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and th ...

along with the annotation "not to be re-enlisted".

World War II

Australia

Hubbard joined the

Hubbard joined the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during the summer of 1941, a few months before the United States entered the Second World War. He applied in March 1941 and was commissioned as a lieutenant, junior grade

Lieutenant junior grade is a junior commissioned officer rank used in a number of navies.

United States

Lieutenant (junior grade), commonly abbreviated as LTJG or, historically, Lt. (j.g.) (as well as variants of both abbreviations), i ...

in the Naval Reserve on July 19, 1941. Hubbard was called to active duty in November. He specifically volunteered for "Special Service (intelligence duties)", an assignation recorded on his commission papers. He spent only a brief time in this nominal role with the Office of Naval Intelligence

The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) is the military intelligence agency of the United States Navy. Established in 1882 primarily to advance the Navy's modernization efforts, it is the oldest member of the U.S. Intelligence Community and serves ...

. After four months working in public relations and at the US Hydrographic Office, he spent three weeks at the Third Naval District

The naval district was a U.S. Navy military and administrative command ashore. Apart from Naval District Washington, the Districts were disestablished and renamed Navy Regions about 1999, and are now under Commander, Naval Installations Comman ...

in New York training for the role of Intelligence Officer.

Hubbard's training was curtailed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

on December 7, 1941, and on December 18 he was sent to the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

via Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

. He was put ashore in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

in January 1942 when his ship was re-routed. In 1963, Hubbard told Australian journalists that he had been "the only anti-aircraft battery in Australia in 1941–42... There was me and a Thompson submachine gun

The Thompson submachine gun (also known as the "Tommy Gun", "Chicago Typewriter", "Chicago Piano", “Trench Sweeper” or "Trench Broom") is a blowback-operated, air-cooled, magazine-fed selective-fire submachine gun, invented by United Stat ...

... I was a mail officer and I was replaced, I think, by a Captain, a couple of commanders and about 15 junior officers."

Another Church of Scientology account describes Hubbard as "Senior Officer Present Ashore in Brisbane, Australia" and asserts that "his duties included counter-intelligence and the organization of relief for beleaguered American forces on Bataan

Bataan (), officially the Province of Bataan ( fil, Lalawigan ng Bataan ), is a province in the Central Luzon region of the Philippines. Its capital is the city of Balanga while Mariveles is the largest town in the province. Occupying the entir ...

." Hubbard would claim that he had "sent on my own authority, four cargo ships loaded to the gunwales with machine gun ammunition, rifle ammunition and quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg cr ...

up to MacArthur." Col. Merle-Smith, the US Naval Attaché to Australia, subsequently accused Hubbard of sending blockade-runner '' Don Isidro'' "three thousand miles out of her way". Hubbard was ordered back to the United States at the instigation of the Attaché, who cabled Washington to complain about Hubbard:

Hubbard would later recall: "for the next two or three years I'd run into officers, and they would say "Hubbard? Hubbard? Hubbard? Are you the Hubbard that was in Australia?" And I'd say "Yes." And they's say "Oh!" Kind of, you know, horrified, like they didn't know whether they should quite talk to me or not, you know? Terrible man".

Hubbard stated on another occasion that he had been "one of the first officers back from the upper battle areas" and when "Melbourne found out ... there were enough troops in the area so the danger was over, so I went home. I wrote myself some orders and reported back to the US." According to the Church of Scientology, Hubbard was landed on the island of Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

"in the closing days of February 1942" to search for "stockpiled weapons and fast, shallow-draft vessels". He was cut off by invading Japanese "and was only able to escape the island after scrambling into a rubber raft and paddling out to meet an Australian destroyer".

In a 1956 lecture to Scientologists, Hubbard said:

In another lecture of the same year, Hubbard provided an alternative version of his return to the United States:

The US Navy's files do not record Hubbard spending any time on Java and do not show any evidence of wounds or injuries sustained in combat.

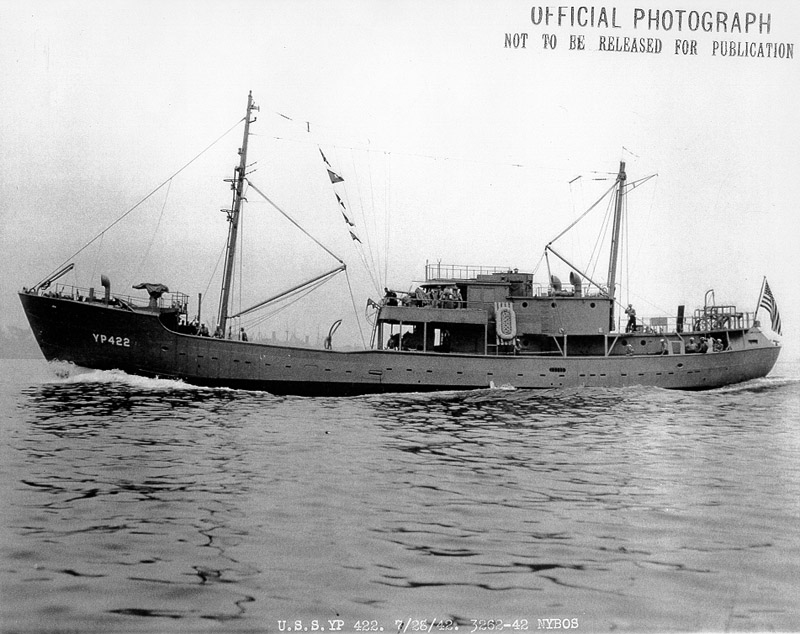

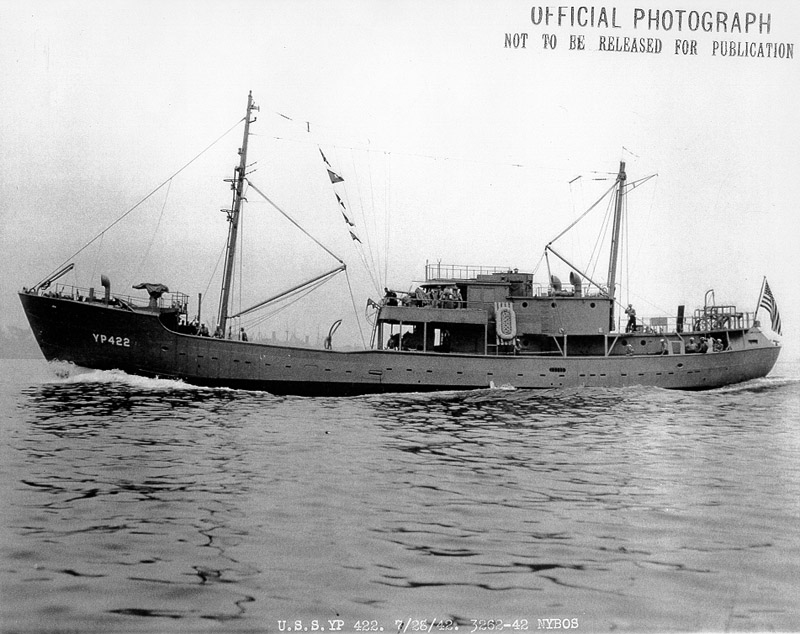

Atlantic service: USS ''YP-422'' and after

Hubbard was posted to the Office of the Cable Censor in

Hubbard was posted to the Office of the Cable Censor in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

after returning to the US at the end of March 1942. As the office had recently ceased to be an organ of Naval Intelligence, his status was amended to deck officer. He was also promoted (as part of a batch of other officers of the same grade) on June 15, 1942, to lieutenant, senior grade, the highest rank he was to hold during his active service.

In June 1942 he requested that he be assigned to sea duty in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

; he was sent instead to the shipyard of George Lawley & Son of Neponset, Massachusetts

Neponset is a district in the southeast corner of Dorchester, Boston, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing s ...

, where the fishing trawler MV ''Mist'' was being converted for military use as a naval yard patrol (YP) vessel. Atack, pp. 73–74. The navy commandeered numerous fishing vessels and redesignated them as YP boats, tasked with defending coastal waters against enemy submarines and delivering food and equipment to military personnel offshore; they were particularly prized for having refrigeration units. The vessel was commissioned as on July 28, 1942, having been refitted as a freighter armed with a 3-inch deck gun and two .30-caliber machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

s. In August, ''YP-422'' put to sea from the Boston Navy Yard to carry out a 27-hour training exercise.

However, Hubbard fell out with a senior officer at the shipyard and sent a critical memorandum to the Vice-Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO) in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The Commandant of the Navy Yard responded on September 25, 1942, by informing the VCNO that, in his view, Hubbard was "not temperamentally fitted for independent command" and requesting that Hubbard be removed and ordered to "other duty under immediate supervision of a more senior officer". Hubbard duly lost his command on October 1, 1942, and was ordered to New York, ending his service in the Atlantic.

Various accounts of Hubbard's service in the North Atlantic have been put forward by the Church of Scientology and Hubbard himself. The Church of Scientology states in one publication that Hubbard "took command of an antisubmarine escort vessel with Atlantic convoys". In a 1954 lecture, Hubbard asserted that he had been sent "to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in the very early part of the war to take command of a corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

" and had been given a crew made up of convicts from the Portsmouth Naval Prison

Portsmouth Naval Prison is a former U.S. Navy and Marine Corps prison on the grounds of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard (PNS) in Kittery, Maine. The building has the appearance of a castle. The reinforced concrete naval prison was occupied from 190 ...

. Hubbard stated in another lecture that he had been posted aboard "corvettes, North Atlantic. And I went on fighting submarines in the North Atlantic and doing other things and so on. And I finally got a set of orders for the ship. By that time I had the squadron."

Biographical accounts published by the Church of Scientology have described Hubbard as commanding the "Fourth British Corvette Squadron" and Hubbard himself stated that he "was running British corvettes during the war". A biographical interview with Hubbard published in 1956 speaks of him commanding "the former British corvette, the ''Mist''". (The only British naval vessel named ''Mist'' was an Admiralty drifter, one of a number of small wooden vessels constructed for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in 1918.) Hubbard also asserted that he had sustained wounds "aboard a corvette in the North Atlantic". A biographical profile published in 2008 by the Scientology-related imprint Galaxy Press

Galaxy Press is a trade name set up to publish and promote the fiction works

of L. Ron Hubbard, and the anthologies of the L. Ron Hubbard Writers of the Future contest.

The company was separated from Bridge Publications in the early 2000s, and ...

asserts that Hubbard "served with distinction in four theaters and was highly decorated for commanding corvettes in the North Pacific. He was also grievously wounded in combat ndlost many a close friend and colleague ..."

In November 1942, Hubbard was sent to the Submarine Chaser Training Center in Miami, Florida

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, for training on submarine chaser

A submarine chaser or subchaser is a small naval vessel that is specifically intended for anti-submarine warfare. Many of the American submarine chasers used in World War I found their way to Allied nations by way of Lend-Lease in World War II.

...

vessels. He subsequently undertook a ten-day anti-submarine warfare training course at the Fleet Sound School in Key West

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Island, it cons ...

and on January 17, 1943, he was posted to the Albina Engine & Machine Works in Portland, Oregon

Portland (, ) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the most populous co ...

, where he was to take command of the subchaser when she was commissioned. Atack, pp. 74–75.

Pacific service: USS ''PC-815''

When Hubbard arrived in Portland, USS ''PC-815'' was in the last stages of its construction. The ship, a steel-hulled subchaser of the ''PC-461'' class, had been laid down on October 10, 1942, at the Albina shipworks. She was commissioned on April 21, 1943, with Hubbard in command and Lt (jg) Thomas Moulton, an officer with whom he had studied in Florida, as the ship's

When Hubbard arrived in Portland, USS ''PC-815'' was in the last stages of its construction. The ship, a steel-hulled subchaser of the ''PC-461'' class, had been laid down on October 10, 1942, at the Albina shipworks. She was commissioned on April 21, 1943, with Hubbard in command and Lt (jg) Thomas Moulton, an officer with whom he had studied in Florida, as the ship's executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

. The ship left Portland on May 18 to travel down the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

to Astoria, Oregon

Astoria is a port city and the seat of Clatsop County, Oregon, United States. Founded in 1811, Astoria is the oldest city in the state and was the first permanent American settlement west of the Rocky Mountains. The county is the northwest corne ...

, where she took on ammunition. After participating for a day in an air-sea rescue operation, USS ''PC-815'' was ordered to sail to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

to commence its shakedown cruise.

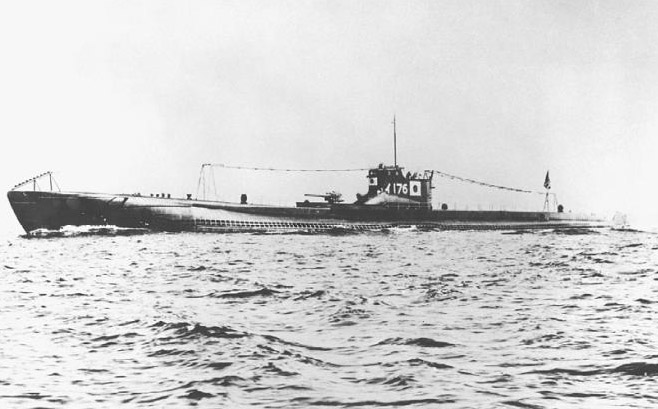

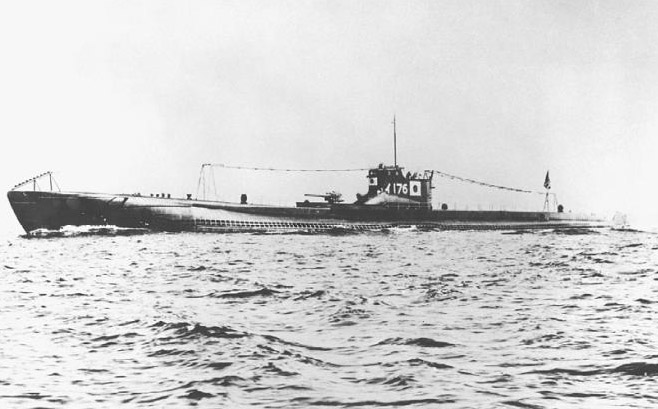

In the early hours of May 19, ''PC-815''s sonar detected what the crew believed to be an enemy submarine off Cape Lookout, about ten to twelve miles offshore. Over the next two and a half days, Hubbard ordered his crew to fire a total of 35 depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive Shock factor, hydraulic shock. Most depth ...

s and a number of gun rounds to target what Hubbard believed to be two Imperial Japanese Navy submarines. ''PC-815'' was joined by the US Navy blimps ''K-39'' and ''K-33'', the US Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, multi ...

patrol boats ''Bonham'' and ''78302'', and the subchasers USS ''SC-536'' and USS ''SC-537,'' to assist it in the search for the suspected enemy vessels. Hubbard was given temporary command of the vessels on the afternoon of May 19. The larger subchaser ''PC-778'' also joined the submarine search, though it found no indication of submarines and its commander was subsequently castigated by Hubbard for his refusal to lay its own larger stock of depth charges or resupply the ''PC-815''. Atack, p. 77–78

Hubbard stated in his eighteen-page after-action report that he had intended to force the submarine to surface so that it could be attacked by the surface vessels' guns. He reported that his vessel had seen oil on the surface, though ''PC-815'' took no samples, and asserted that the blimps had seen air bubbles, oil and a periscope, though the blimps' own reports did not corroborate this. No wreckage was seen, despite the heavy depth-charging. ''PC-815'' sustained some minor damage and three crew were injured during the incident when the ship's radio antenna was accidentally hit by gunfire. At midnight on 21 May, with depth charges exhausted and the presence of a submarine still unconfirmed by any other ship, ''PC-815'' was ordered back to Astoria.

The incident attracted the attention of the naval high command, as there had been a verified Japanese submarine attack against Fort Stevens about further north in June 1942 and there had been an invasion scare

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

in southern California earlier in 1942. Hubbard claimed to have "definitely sunk, beyond doubt" one submarine and critically damaged another. His view was not shared by his superiors. After reviewing the action reports and interviewing Hubbard and the other commanders present, Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher

Frank Jack Fletcher (April 29, 1885 – April 25, 1973) was an admiral in the United States Navy during World War II. Fletcher commanded five different task forces through WWII; he was the operational task force commander at the pivotal battle ...

noted: "An analysis of all reports convinces me that there was no submarine in the area. Lieutenant Commander Sullivan states that he was unable to obtain any evidence of a submarine except one bubble of air which is unexplained except by turbulence of water due to a depth charge explosion. The commanding officers of all ships except the ''PC-815'' state they had no evidence of a submarine and do not think a submarine was in the area." Fletcher also noted that there was a "known magnetic deposit in the area in which depth charges were dropped". The clear implication was that Hubbard had been targeting the deposit all along. Atack, pp. 77–79 Miller, pp. 132–137

Hubbard nonetheless continued to claim that he had sunk at least one Japanese submarine. Years later, in 1956, he told Scientologists:

In another lecture, he commented:

After the war, the

Hubbard nonetheless continued to claim that he had sunk at least one Japanese submarine. Years later, in 1956, he told Scientologists:

In another lecture, he commented:

After the war, the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

and the US Navy analysed the captured records of the Japanese navy to account for all of its vessels. Their reports do not list any Japanese submarine losses off the coast of the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

during the whole of the war. According to military records, ''I-76'' was destroyed off Buka Island in the western Pacific by , and on May 16, 1944. Hubbard's crew however, who were very loyal to him, shared his conviction that they had engaged an enemy submarine. His second-in-command, Thomas Moulton, later asserted that the Navy had hushed up the incident, fearing that the presence of Japanese submarines so close to the Pacific coast might cause panic.

Following its return to Astoria, USS ''PC-815'' was ordered to escort a new aircraft carrier to San Diego, where the subchaser was to participate in exercises. Miller, p. 138 On June 28, 1943, Hubbard ordered his crew to fire four shells from the ship's 3-inch gun and a number of rifle and pistol shots in the direction of the Coronado Islands, off which the ship anchored for the night. He did not realize that the islands belonged to

Following its return to Astoria, USS ''PC-815'' was ordered to escort a new aircraft carrier to San Diego, where the subchaser was to participate in exercises. Miller, p. 138 On June 28, 1943, Hubbard ordered his crew to fire four shells from the ship's 3-inch gun and a number of rifle and pistol shots in the direction of the Coronado Islands, off which the ship anchored for the night. He did not realize that the islands belonged to Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, an ally, nor that he had taken USS ''PC-815'' into Mexican territorial waters. Miller, p. 139 The islands were garrisoned by Mexican Navy personnel during the war.

The Mexican government complained and two days later, Hubbard found himself before a naval Board of Investigation in San Diego. He was found to have disregarded orders by carrying out an unsanctioned gunnery practice and violating Mexican waters. He was reprimanded and removed from command, effective July 7. Rear Admiral Frank A. Braisted commented, in a fitness report written shortly after the Coronado incident, that he "''consider dthis officer lacking in the essential qualities of judgment, leadership and cooperation. He acts without forethought as to probable results. He is believed to have been sincere in his efforts to make his ship efficient and ready. Not considered qualified for command or promotion at this time. Recommend duty on a large vessel where he can be properly supervised.''" Atack, p. 80

USS ''Algol'' and shore service

On the same day that Hubbard was sent a formal letter of admonition, he reported sick with complaints of epigastric pains and possible

On the same day that Hubbard was sent a formal letter of admonition, he reported sick with complaints of epigastric pains and possible malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

. In his Affirmations, Hubbard later recorded: "Your stomach trouble you used as an excuse to keep the Navy from punishing you." Wright, p. 53

After 77 days on the sick list, it was finally determined that he was suffering from a duodenal ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the inner lining of the stomach, the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while one in the first part of the intestines ...

. In October 1943, he asked to be transferred to landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

and was sent on a six-week training course at the Naval Small Craft Training Center in San Pedro, California

San Pedro ( ; Spanish: " St. Peter") is a neighborhood within the City of Los Angeles, California. Formerly a separate city, it consolidated with Los Angeles in 1909. The Port of Los Angeles, a major international seaport, is partially located wi ...

. Miller, p. 140 He was then ordered in December 1943 to join the crew of , an attack cargo ship, to assist with the ship's fitting out and crew training in Portland, Oregon. The vessel was commissioned in July 1944 with Hubbard aboard in the role of Navigation and Training Officer. Atack, p. 81 The next two months were occupied with training exercises off the California coast in preparation for the ship's envisaged departure in September for the western Pacific theater of operations.

Hubbard, however, applied instead to undertake a three-month training course in military administration at the School of Military Government, a faculty that had been established on the campus of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

, but was not part of the University itself, although Hubbard later asserted that he had been a Princeton student. Miller, p. 141 His commanding officer approved the detachment and gave Hubbard a generally good fitness report, rating him to be "of excellent personal and military character" though he "is very temperamental and often has his feelings hurt". On September 27, a curious incident occurred aboard USS ''Algol''; the ship's deck log records that Hubbard reported that he had discovered "an attempt at sabotage" consisting of a Coke bottle filled with gasoline with a cloth wick inserted, concealed among the ship's cargo. A few hours later Hubbard was ordered to depart the ship and proceed to Princeton.

In later years, Hubbard asserted that the 1955 film '' Mister Roberts'' was based on his service aboard USS ''Algol'' with Henry Fonda's eponymous character being based on Hubbard himself and James Cagney

James Francis Cagney Jr. (; July 17, 1899March 30, 1986) was an American actor, dancer and film director. On stage and in film, Cagney was known for his consistently energetic performances, distinctive vocal style, and deadpan comic timing. He ...

's tyrannical character based on the commander of ''Algol''. In a February 1956 lecture, Hubbard told Scientologists: "There was a story made about that vessel 'Algol'' by the way. It was called ''Mister Roberts''. You may have seen this picture or read the book." According to a Church of Scientology publication,

George Malko comments that "this laim

Laim (Central Bavarian: ''Loam'') is a district of Munich, Germany, forming the 25th borough of the city. Inhabitants: c. 49.000 (2005)

History

Originally its own independent locality, Laim was in existence before Munich. It was first documented ...

has never been substantiated" and notes that the author of the original novel, Thomas Heggen

Thomas Heggen (December 23, 1918 – May 19, 1949) was an American author best known for his 1946 novel '' Mister Roberts'' and its adaptations to stage and screen. Heggen became an Oklahoman in 1935, when in the depths of the Depression h ...

, "would only say about Roberts: "He is too good to be true, he is a pure invention."" The novel was reportedly "loosely based on eggen'sservice on the ".

At the conclusion of his course at the School of Military Government, Hubbard failed to pass his examinations – finishing only mid-way down the class list – and did not qualify for an overseas posting. He was posted in January 1945 to the Naval Civil Affairs Staging Area in Monterey, California

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bo ...

, for further training but, as he later acknowledged, he became depressed and fell ill with a duodenal ulcer. He reported sick with stomach pains in April 1945 and spent the remainder of the war on the sick list as a patient in Oak Knoll Naval Hospital

Naval Hospital Oakland, also known as Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, was a U.S. naval hospital located in Oakland, California that opened during World War II (1942) and closed in 1996 as part of the 1993 Base Realignment and Closure program. The site ...

in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

. Atack, p. 82 A Church of Scientology account asserts that "eventual combat wounds would finally preclude him from serving with American occupation forces".

In October 1945, a Naval Board found that he was "considered physically qualified to perform duty ashore, preferably within the continental United States", in reflection of his chronic ulcer. He was discharged from the hospital and mustered out of active service on December 6, 1945. Atack, p. 84 He resigned his commission in October 1950. According to the Church of Scientology, he quit because the US Navy had "attempted to monopolize all his researches and force him to work on a project "to make man more suggestible" and when he was unwilling, tried to blackmail him by ordering him back to active duty to perform this function. Having many friends he was able to instantly resign from the Navy and escape this trap." Hubbard himself told Scientologists:

According to the US Navy, "There is no evidence on record of an attempt to recall him to active duty."Original (18M)Alleged war wounds

As the psychologist and computer scientist Christopher Evans has noted, "One aspect of ubbard'swar record that is particularly confused, and again typical of the mixture of glamour and obscurantism which surrounds Hubbard and his past, is the matter of wounds or injuries suffered on active service." Hubbard asserted after the war that he had been "blinded with injured optic nerves, and lame with physical injuries to hip and back... Yet I worked my way back to fitness and strength in less than two years, using only what I knew about Man and his relationship to the universe." Accounts published by the Church of Scientology asserted that he had been "flown home in the late spring of 1942 in the secretary of the Navy's private plane as the first U.S.-returned casualty from the Far East". A 2006 publication goes further, describing him as "the first American casualty of South Pacific combat". Thomas Moulton, Hubbard's executive officer on USS ''PC-815'', testified in 1984 that Hubbard had said that he had been shot in theDutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

, and that on another occasion Hubbard had told him that his eyes had been damaged by the flash of a large-caliber gun. Hubbard himself told Scientologists in a taped lecture that he had suffered eye injuries after having had "a bomb go off in my face." He told Robert Heinlein, the science fiction writer, that "both of his feet had been broken (drumhead-type injury) when his last ship was bombed". It is important to note that a drumhead injury was not a foot injury, but rather an injury to the eardrum ( tympanic membrane), a common war injury at the time. According to Heinlein, Hubbard said that he "had had a busy war – sunk four times and wounded again and again". Hubbard was said to have been "twice been pronounced dead" and to have spent a year in a naval hospital which he "utilized in the study of endocrine substances and protein". The techniques that he developed "made possible not only his own recovery from injury, but helped other servicemen to regain their health". On another occasion, Hubbard said that he had been hospitalized because "I was utterly exhausted. I'd just been in combat theater after combat theater, you see, with no rest, no nothing between."

This account was challenged by a series of writers and journalists from the mid-1970s onwards. Writing in 1974, Evans noted that the Veterans Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing life-long healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers and ...

had confirmed that (even at that late stage in his life) Hubbard "receives $160 a month in compensation for disabilities incurred during the Second World War. However the conditions listed as being '40% disabling' are: duodenal ulcer, bursitis

Bursitis is the inflammation of one or more bursae (fluid filled sacs) of synovial fluid in the body. They are lined with a synovial membrane that secretes a lubricating synovial fluid. There are more than 150 bursae in the human body. The bursa ...

(right shoulder), arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

, and blepharoconjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis, also known as pink eye, is inflammation of the outermost layer of the white part of the eye and the inner surface of the eyelid. It makes the eye appear pink or reddish. Pain, burning, scratchiness, or itchiness may occur. The ...

." Evans noted: "a Navy Department spokesman has stated that 'an examination of Mr Hubbard's record does not reveal any evidence of injuries suffered while in the service of the United States Navy'."

Sixteen years later, the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

'' obtained Hubbard's medical records through the Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

. The records stated that Hubbard had told doctors that he had been "lamed" by a chronic hip infection, and that his eye problems were the result of conjunctivitis caused by exposure to "excessive tropical sunlight". Hubbard's post-war correspondence with the VA was also included, including letters in which he requested psychiatric treatment to address his "long periods of moroseness" and "suicidal inclinations". He continued to complain to the VA about various physical ailments into the 1950s, well after he had founded Dianetics

Dianetics (from Greek ''dia'', meaning "through", and ''nous'', meaning "mind") is a set of pseudoscientific ideas and practices regarding the metaphysical relationship between the mind and body created by science fiction writer L. Ron Hubba ...

. The ''Times'' noted that Hubbard had promised that Dianetics would provide "a cure for the very ailments that plagued the author himself then and throughout his life, including allergies, arthritis, ulcers and heart problems". Other documents on Hubbard's medical file stated that he had injured his back in 1942 after falling off a ship's ladder.

Claimed medals

Hubbard's war medals have also been an issue of contention. Although the Church of Scientology has stated that Hubbard was "highly decorated for duties under fire", the actual number of decorations said to have been awarded to Hubbard has varied considerably over the years. In a 1968 interview with British journalists, Hubbard showed his visitors sixteen war medals that he claimed to have been awarded. Miller, p. 290 A few months later, the Church of Scientology published a "Data Sheet on Lafayette Ron Hubbard" that stated that he had been awarded "Twenty-one medals and palms". (The "Data Sheet" lists Hubbard as the Commanding Officer (CO) of the USS ''Holland.) In May 1974, the Church asked the Navy Department to supply seventeen medals that he was said to have been awarded, including thePurple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, w ...

and Navy Commendation Medal, many of them with bronze service stars

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

denoting participation in military campaigns or multiple bestowals of the same award. The Navy sent only four medals, noting, "The records in this Bureau fail to establish Mr. Hubbard's entitlement to the other medals and awards listed in your response." Hubbard responded by circulating to Scientologists a photograph of 21 medals and palms that he said he had been awarded and explained that he had actually won 28, but that the missing seven had been awarded to him in secret because the naval high command was embarrassed that he had sunk two Japanese submarines in the United States' "back yard". Miller, p. 424–25 A 1994 biography published by the Church of Scientology states that he was awarded 29 medals and awards.

In 1990 the Church of Scientology released a document, said to be a copy of Hubbard's official record of service, to support its assertion that Hubbard had been awarded 21 medals and decorations. The Church asserts that Hubbard was awarded a "Unit Citation A unit citation is a formal, honorary mention by high authority of a military unit's specific and outstanding performance, notably in battle.

Similar mentions can also be made for individual soldiers.

Alternatively or concurrently, the unit can be ...

which is only awarded by the President to combat units that perform particularly meritorious service." Among the other awards listed on the record released by the Church is the British Victory Medal, an award issued for service in the British armed forces in the ''First'' World War and that was never awarded by itself. The Church's document also credits Hubbard with a Purple Heart with a Palm, implying two wounds received in action. However, the U.S. Navy uses gold and silver stars, not a palm, to indicate multiple wounds. The Church has distributed a photograph of medals said to have been won by Hubbard; two of the medals (specifically the National Defense Service Medal and the Armed Forces Reserve Medal) were not even created until after Hubbard left active service.

The Church's record lists Hubbard as commanding the "USS ''Mist''". Although USS ''YP-422'' was originally named ''Mist'' when it was in civilian service, it was never called USS ''Mist''; the only 20th-century US Navy vessel of that name listed in the '' Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships'' left naval service in 1919, when Hubbard was six years old. It is signed by "Howard D. Thompson, Lt. Cmdr.", who is not listed in the records of commissioned naval officers at that time. Archivist Eric Voelz of the National Personnel Records Center told ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' that the document is a forgery.

The ''Los Angeles Times'' commented, and NPR later confirmed, that the US Navy's version of the same record – a DD Form 214

DD, dd, or other variants may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*"D.D.", a track on mixtape ''Echoes of Silence'' by The Weeknd

* DD (character), a character in ''The Saga of Seven Suns'' novels by Kevin J. Anderson

*DD National or DD1, an Indi ...

– "indicates Hubbard received four medals during his Navy career, as well as two marksmanship medals" and noted "discrepancies" with the Scientology version. The four medals that the US Navy's record credits to Hubbard were the American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recognize those military service members who had served ...

, which was awarded to all members of the military in service at the time of the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

; the American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

, awarded to all service members who had performed duty in the American Theater of Operations during the war; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, awarded to all who had served in the Pacific Theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

; and the World War II Victory Medal, awarded to all who served during World War II. Miller, p. 144 According to the Department of the Navy, there was "no record of the additional decorations the church says Hubbard received".

Church officials have argued the Navy's records were "not only grossly incomplete but perhaps were falsified to conceal Hubbard's secret activities as an intelligence officer". In the 1980s the Church turned to L. Fletcher Prouty

Leroy Fletcher Prouty (January 24, 1917 – June 5, 2001)Carlson, Michael"L Fletcher Prouty: US officer obsessed by the conspiracy theory of President Kennedy's assassination"(obituary). ''The Guardian'' (June 21, 2001). Archived frothe original. ...

, a former U.S. Army colonel, who said that Hubbard's records had been falsified to cover up his "intelligence background". Prouty, who died in 2001, was a prominent conspiracy theorist best known for advocating John F. Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 spawned numerous conspiracy theories. These theories allege the involvement of the CIA, the Mafia, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro, the K ...

and was also associated with the anti-semitic Liberty Lobby group and the Lyndon LaRouche organization.

Documenting Hubbard's military career

Hubbard's military career has attracted comment from a number of journalists and writers over the years. The claims made by the Church of Scientology were not challenged by some early writers; C.H. Rolph quoted without comment a 1968 Scientology biographical sketch circulated to British

Hubbard's military career has attracted comment from a number of journalists and writers over the years. The claims made by the Church of Scientology were not challenged by some early writers; C.H. Rolph quoted without comment a 1968 Scientology biographical sketch circulated to British Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

in which Hubbard's war service was summarized, and in 1971 Paulette Cooper described as "true" the claim that Hubbard "was severely injured in the war (and in fact was in a lifeboat for many days, badly injuring his body and his eyes in the hot Pacific sun)". Others were more skeptical. George Malko attempted to verify Hubbard's "revealing, anonymously authored, and totally unsubstantiated biography" in 1970 but reported that "I was unable to confirm a single one of ubbard'scritical claims: that he had been crippled and blind, the nature of his 'discoveries,' and the medical records stating he had 'twice been pronounced dead. His inquiries were frustrated by the Navy's refusal to provide Hubbard's service record "without the written consent of the person whose records are concerned".

Information later released by the Navy and the Veterans Administration prompted some to express doubts. Christopher Evans commented in 1974 that "faced with this impressive, if annoyingly undetailed, record it is hard to assess the nature or extent of Hubbard's battle scars in the service of his country" but noted contradictions between claims of war wounds and the official record. In 1978, the ''Los Angeles Times'' described Hubbard's war record as "obscure" and quoted Navy spokesmen stating that Hubbard had not received a Purple Heart and had not been treated for any injuries sustained during his military career, contrary to the statements of the Church of Scientology.

By 1979, an amateur researcher, Michael Shannon, had gathered "a mountain of material which included some files that no one else had bothered to get copies of – for example, the log books of the Navy ships that Hubbard had served on, and his father's Navy service file". Although Shannon was unable to find a publisher, he sent a hundred-page portfolio of materials, including copies of some of Hubbard's naval and college records, to a number of "concerned individuals". His work also found its way to the Church of Scientology's archivist, Gerry Armstrong, who was undertaking a project to research an official authorized biography of L. Ron Hubbard. According to Jon Atack

''A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics and L. Ron Hubbard Exposed'' is a 1990 book about L.Ron Hubbard and the development of Dianetics and Scientology, authored by British former Scientologist Jon Atack. It was republished in 2013 with the ...

, "the archive largely confirmed Shannon's material. Armstrong and Shannon reached the same eventual destination from opposed starting points." In October 1980, Omar Garrison, a writer who had previously written two books favorable to Scientology, was hired by the Church to write Hubbard's biography based on the materials that Armstrong had collected.

Armstrong became disillusioned and left Scientology at the start of 1982. He was declared a " Suppressive Person" (an enemy of Scientology) by the Church. With Garrison's permission, Armstrong made copies of around 100,000 pages from the Hubbard archive and deposited them with attorneys for safe keeping. The Church responded by suing Armstrong for breach of confidence, theft and invasion of privacy. The suit went to trial in a California court in 1984 as '' Church of Scientology of California vs. Gerald Armstrong''. Hubbard's military career was a major focus of the case. Armstrong stated that he had "amassed approximately two thousand pages of documentation concerning Hubbard's wartime career: what he was doing what vessels he was on, fitness reports and medical and VA disability records. The truth is far different from the public representations." Garrison, who had by that time agreed to a settlement with the Church under which his manuscript would never be made public, told the court:

During the trial's four weeks of testimony, the court heard evidence from Thomas S. Moulton, Hubbard's second-in-command aboard the USS ''PC-815''. Moulton testified that Hubbard had told him that he had been involved in the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 and that he had been the only survivor of his destroyer, which had gone down with all hands save himself. The "submarine battle" of May 1943 was also described by Moulton and was hailed by a Church of Scientology attorney as "a new untold chapter to the history of the Pacific conflict during World War II; and new perspectives on the magnitude – and proximity – of Japanese naval operations off the U.S. coast during the war". Moulton also testified that Hubbard had told him that he had received combat injuries to his eyes and back. In response, documents contradicting Moulton's (and Hubbard's) account were read into the record by Armstrong's attorney, Michael Flynn.

The decision, by Judge Paul Breckenridge, found that Armstrong's fears of persecution by the Church were reasonable, and thus his conduct in turning over the documents in his possession to his attorneys was also reasonable. The judge issued a wide-ranging verdict, commenting of Hubbard that "the evidence portrays a man who has been virtually a pathological liar when it comes to his history, background and achievements." A few weeks later, a British judge ruled in a case heard at the Royal Courts of Justice that Hubbard had made a number of "false claims" about his military career: "That he was a much decorated war hero. He was not. That he commanded a corvette squadron. He did not. That he was awarded the Purple Heart, a gallantry decoration for those wounded in action. He was not wounded and was not decorated. That he was crippled and blinded in the war and cured himself with Dianetics techniques. He was not crippled and was not blinded." The judge, Mr. Justice Latey, noted: "There is no dispute about any of this. The evidence is unchallenged."Re B & G (Minors)

985' Family Law Reports 134 and 493. Retrieved 2009-07-14. Hubbard's military service has subsequently been covered in detail by the British writers

Russell Miller

Russell Miller (born 1938) is a British journalist and author of fifteen books, including biographies of Hugh Hefner, J. Paul Getty and L. Ron Hubbard.

While under contract to ''The Sunday Times Magazine'' he won four press awar ...

(''Bare-faced Messiah

''Bare-faced Messiah: The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard'' is a posthumous biography of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard by British journalist Russell Miller. First published in the United Kingdom on 26 October 1987, the book takes a critical p ...

'', 1987) and Jon Atack (''A Piece of Blue Sky

''A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics and L. Ron Hubbard Exposed'' is a 1990 book about L.Ron Hubbard and the development of Dianetics and Scientology, authored by British former Scientologist Jon Atack. It was republished in 2013 with the ...

'', 1990), by the ''Los Angeles Times'' in a six-part special report on Scientology published in June 1990, and by Lawrence Wright in ''The New Yorker'' in February 2011 and his book '' Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief'' (2013). The accuracy of Miller's account has been questioned; Marco Frenschkowski, writing in 1999, commented that Miller's book had "definitely exposed some inflated statements about Hubbard's early achievements" but had also been partly disproved by the Church of Scientology, though he did not state which elements had been disproved.

Naval career of Harry Ross Hubbard

L. Ron Hubbard's father, Lieutenant Commander Harry Ross Hubbard (1886–1975), was a United States Navy Supply Corps officer who served for over 30 years. His career included service during both world wars. He first enlisted in the Navy on September 1, 1904, and served until October 31, 1908. He then re-enlisted duringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on October 10, 1917, and was commissioned an assistant paymaster (with the rank of ensign) in the Supply Corps on October 16, 1918. He was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) on November 11, 1919. He was released from active duty on June 28, 1920, and was placed in an inactive status in the Naval Reserve.

He was commissioned in the Regular Navy and returned to active duty on September 17, 1921. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1922 and lieutenant commander in 1934. Although most Navy officers were promoted rapidly during World War II, Hubbard remained a lieutenant commander for the remainder of his career.

Hubbard's career included a number of routine assignments including: assistant paymaster for the submarine tender in 1918; supply officer for the aircraft tender (1919–1920) (during Hubbard's assignment to ''Aroostook'' she provided support to the historic NC-4

The NC-4 was a Curtiss NC flying boat that was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, albeit not non-stop. The NC designation was derived from the collaborative efforts of the Navy (N) and Curtiss (C). The NC series flying boats w ...

transatlantic flight); assistant supply officer for the battleship (1921–1923); under instruction at the School of Application of the Bureau of Supply and Accounts in Washington, D.C. (1923–1924); disbursing officer at the Puget Sound Navy Yard (1924–1927); officer in charge of the commissary at Naval Station Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

(1927–1929); disbursing officer Naval Hospital, Washington, D.C. (1927–1929); assistant supply officer, Puget Sound Navy Yard (1935–1938); and supply officer of the cruiser (1938–1941).

During World War II, Hubbard served officer in charge of the commissary at Mare Island Navy Yard (1941–1943); supply officer for the destroyer tender (1943–1945); and supply officer of Naval Station, Seattle, Washington (1945–1946), after which he retired.

While Hubbard was assigned to the destroyer tender ''Black Hawk'' during the last two years of the war, the ship was stationed at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

and Adak, Alaska. This was Hubbard's only service outside the continental United States during the war.

Commander Hubbard remained on active duty until he retired from the Navy in May 1946 at the age of 59, after a total of 32 years and 9 months of service.

Dates of rank

* Enlisted service, USN - 1 September 1904 to 31 October 1908 and 10 October 1917 to 15 October 1918 * Assistant Paymaster (with rank of ensign), USNRF - 16 October 1918 * Assistant Paymaster (with rank of lieutenant, junior grade), USNRF - 11 November 1919 * Released from active duty, inactive duty in Naval Reserve - 28 June 1920 * Returned to active duty as Assistant Paymaster (with rank of lieutenant, junior grade), USN - 17 September 1921 * Passed Assistant Paymaster (with rank of lieutenant), USN - 1 September 1922 * Paymaster (with rank of lieutenant commander), USN - 1 May 1934 * Retired - 31 May 1946Awards

* World War I Victory Medal *American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recognize those military service members who had served ...

with "FLEET" clasp

* American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

* Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

* World War II Victory Medal

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Military Career Of L. Ron Hubbard L. Ron HubbardHubbard Hubbard may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hubbard, Saskatchewan

*Hubbards, Nova Scotia

Canada/United States

* Mount Hubbard, a mountain on the Alaska/Yukon border

*Hubbard Glacier, a large freshwater glacier in Alaska and Yukon

Greenland

*Hubbard Gla ...

Hubbard Hubbard may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hubbard, Saskatchewan

*Hubbards, Nova Scotia

Canada/United States

* Mount Hubbard, a mountain on the Alaska/Yukon border

*Hubbard Glacier, a large freshwater glacier in Alaska and Yukon

Greenland

*Hubbard Gla ...

Hubbard Hubbard may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hubbard, Saskatchewan

*Hubbards, Nova Scotia

Canada/United States

* Mount Hubbard, a mountain on the Alaska/Yukon border

*Hubbard Glacier, a large freshwater glacier in Alaska and Yukon

Greenland

*Hubbard Gla ...

Hubbard Hubbard may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hubbard, Saskatchewan

*Hubbards, Nova Scotia

Canada/United States

* Mount Hubbard, a mountain on the Alaska/Yukon border

*Hubbard Glacier, a large freshwater glacier in Alaska and Yukon

Greenland

*Hubbard Gla ...

Hubbard Hubbard may refer to:

Places Canada

*Hubbard, Saskatchewan

*Hubbards, Nova Scotia

Canada/United States

* Mount Hubbard, a mountain on the Alaska/Yukon border

*Hubbard Glacier, a large freshwater glacier in Alaska and Yukon

Greenland

*Hubbard Gla ...

es:L. Ron Hubbard#Carrera militar