The military career of Dwight D. Eisenhower began in June 1911, when

Eisenhower

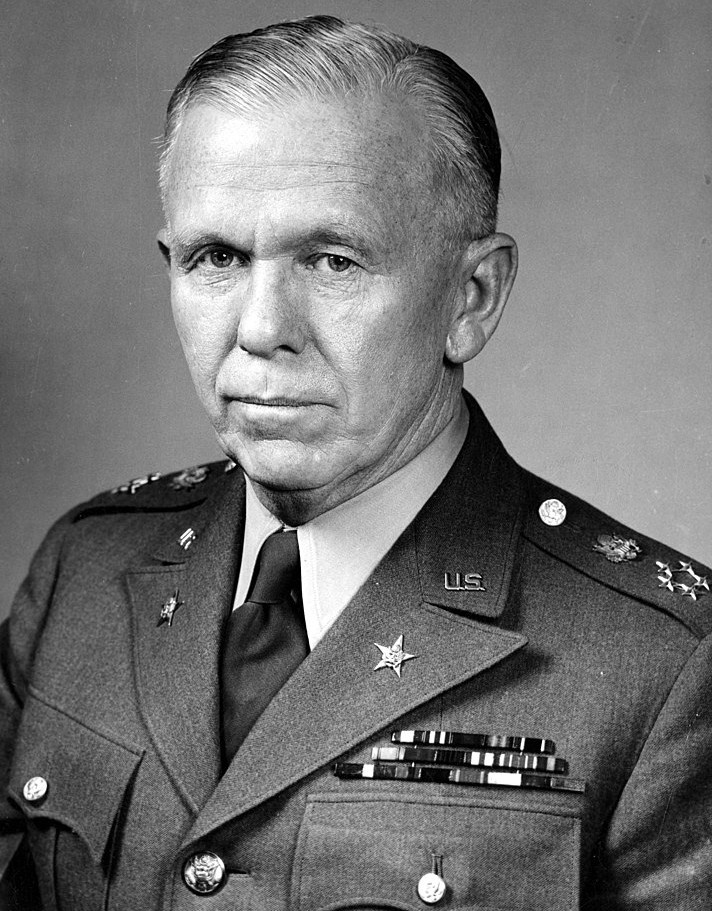

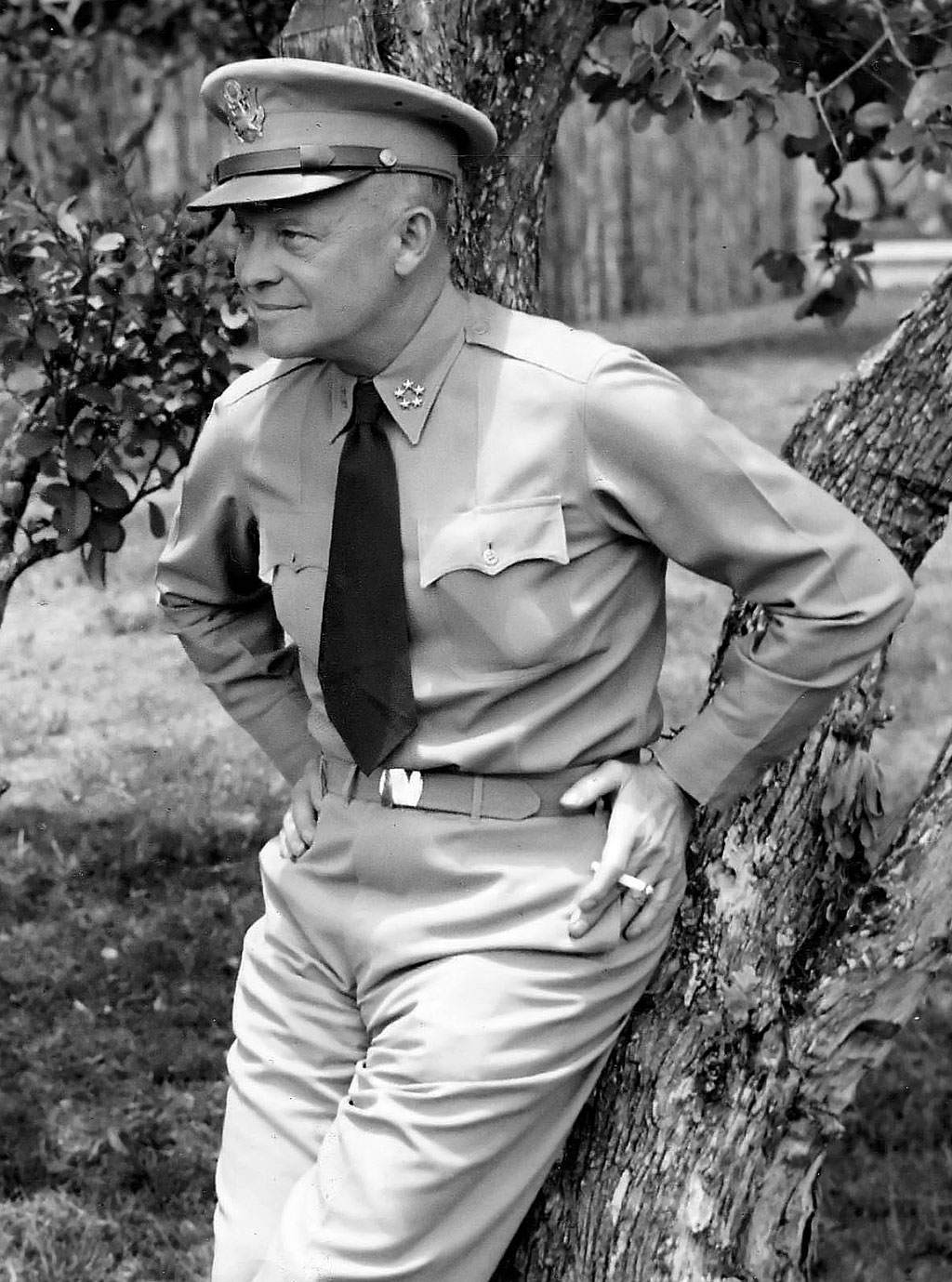

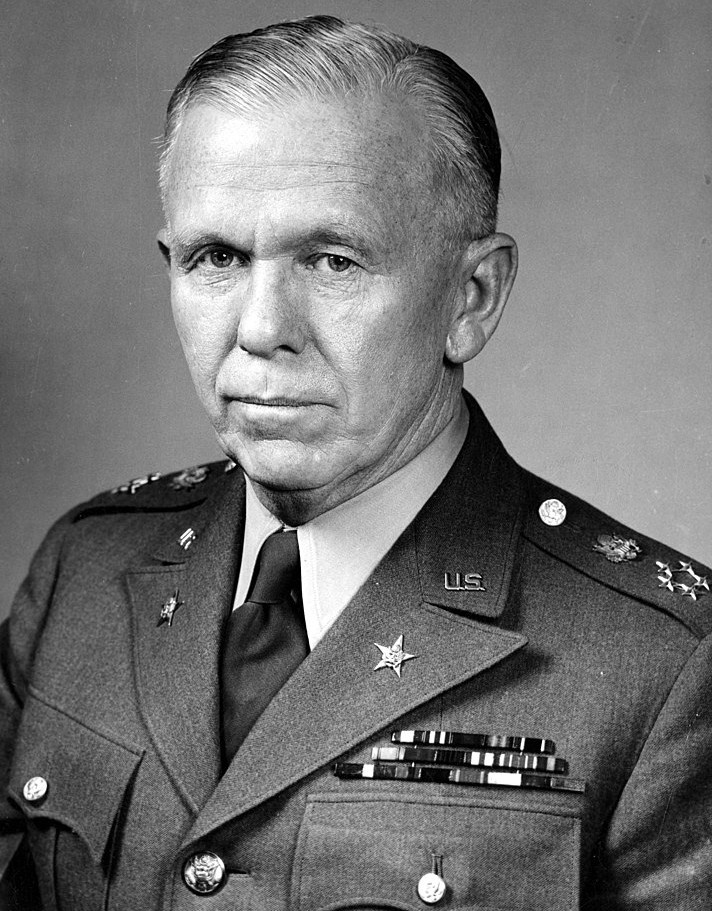

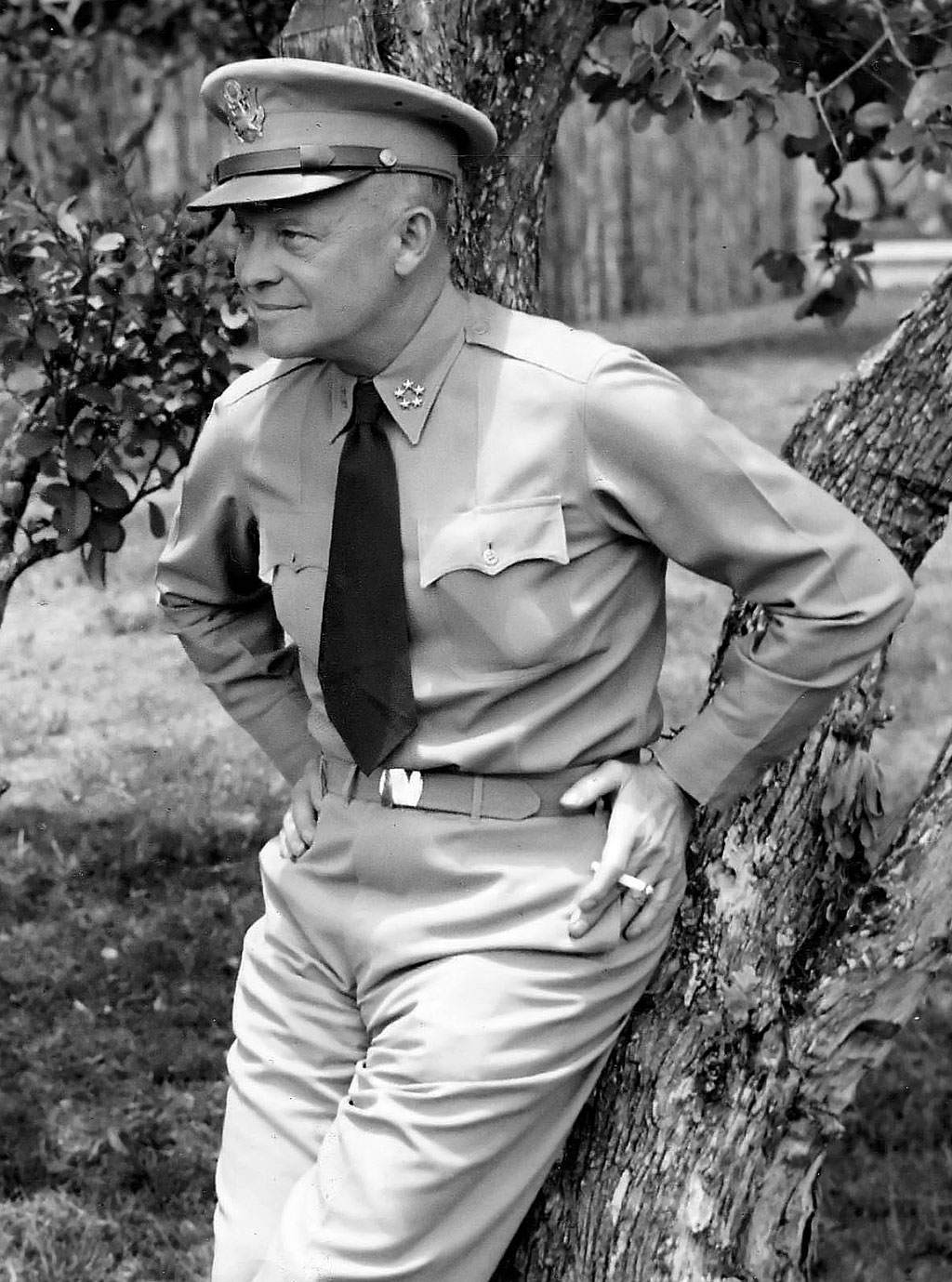

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

took the oath as a cadet at the

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

at West Point. He graduated from West Point and was commissioned as a

second lieutenant in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

in June 1915, in the same class as

Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893April 8, 1981) was a senior officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army. Bradley was the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and over ...

. He rose through the ranks over the next thirty years and became one of the most important

Allied generals of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, being promoted to

General of the Army in 1944. Eisenhower retired from the military after winning the

1952 presidential election, though his rank as General of the Army was restored by an act of Congress in March 1961.

After graduating from the

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1915, Eisenhower was assigned to the

19th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

. He served in the continental United States throughout

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, ending the war as the commander of a battalion that trained tank crews. After the war, he served as part of a

Transcontinental Motor Convoy

The Transcontinental Motor Convoys were early 20th century vehicle convoys, including three US Army truck trains, that crossed the United States (one was coast-to-coast) to the west coast. The 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy from Washington, ...

that traveled across the continental United States. In 1922, he was transferred to the

Panama Canal Zone, where he served under General

Fox Conner

Fox Conner (November 2, 1874 – October 13, 1951) was a Major general (United States), major general of the United States Army. He served as operations officer for the American Expeditionary Force during World War I, and is best remembered as a ...

. He then served on the

American Battle Monuments Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) is an independent agency of the United States government that administers, operates, and maintains permanent U.S. military cemeteries, memorials and monuments primarily outside the United States.

...

under the command of General

John J. Pershing. In 1929, he became the executive officer to General

George Van Horn Moseley

George Van Horn Moseley (September 28, 1874 – November 7, 1960) was a United States Army general. Following his retirement in 1938, he became controversial for his fiercely anti-immigrant and antisemitic views.

Early life and career

Moseley ...

, who served on the staff of

Assistant Secretary of War

The United States Assistant Secretary of War was the second–ranking official within the American Department of War from 1861 to 1867, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1890 to 1940. According to thMilitary Laws of the United States "The act of August 5 ...

Frederick Huff Payne

Frederick Huff Payne (November 10, 1876 – March 24, 1960) was the United States Assistant Secretary of War from 1930 to 1933, under President Herbert Hoover.

Biography

Payne was born on November 10, 1876 in Greenfield, Massachusetts to Samuel ...

. In 1935, Eisenhower accompanied General

Douglas MacArthur to the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where they served as military advisers charged with developing the

Philippine Army

The Philippine Army (PA) (Tagalog: ''Hukbong Katihan ng Pilipinas''; in literal English: ''Army of the Ground of the Philippines''; in literal Spanish: ''Ejército de la Tierra de la Filipinas'') is the main, oldest and largest branch of the ...

. Eisenhower returned to the United States in 1939 and took part in the

Louisiana Maneuvers as the chief of staff to General

Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose fr ...

.

After the United States entered World War II, General

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

assigned Eisenhower to the War Plans Division in Washington, D.C. Eisenhower became the commander of American forces in

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

in June 1942 and was assigned to lead

Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of

French North Africa

French North Africa (french: Afrique du Nord française, sometimes abbreviated to ANF) is the term often applied to the territories controlled by France in the North African Maghreb during the colonial era, namely Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. I ...

. After the success of Operation Torch, Eisenhower led the successful

Allied invasion of Tunisia, forcing the surrender of all Axis forces in May 1943. Eisenhower led the opening phases of the

Italian campaign, but was subsequently assigned to lead the Allied invasion of Western Europe in December 1943. He served as the supreme commander of

Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of

Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, and took command of subsequent operations in France. Following the success of Operation Overlord, the Allies quickly took control of much of Western Europe, but the Germans launched a major counter-attack in the

Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

. German resistance quickly collapsed following the Allied victory in that battle, and Eisenhower accepted the surrender of Germany in May 1945.

After the war, Eisenhower served as the commander of the American zone of occupation in Germany. In November 1945, he succeeded Marshall as the

chief of staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and ...

. Eisenhower left active duty in 1948 to become the president of

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, but rejoined the army in 1951 to become the first supreme commander of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. He left the army once again in 1952 to run for

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

; his presidential candidacy was successful and he served as president from January 1953 to January 1961.

Early years, 1915–1918

Eisenhower graduated with the

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

's class of 1915, "

the class the stars fell on

"The class the stars fell on" is an expression used to describe the class of 1915 at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. In the United States Army, the insignia reserved for generals is one or more stars. Of the 164 gradu ...

", ranked 61st in a class of 164. A knee injured playing football and aggravated while horseback riding that could have caused the government to later give Eisenhower a

medical discharge and disability pension, almost caused the army to not to commission him after graduation. This was acceptable to Eisenhower, who was curious about

gaucho

A gaucho () or gaúcho () is a skilled horseman, reputed to be brave and unruly. The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and the south of Chilean Patagonia. Gauchos became greatly admired and ...

life and began planning a trip to

Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

. West Point's chief medical officer offered to recommend him for a commission in the

Coast Artillery

Coastal artillery is the branch of the armed forces concerned with operating anti-ship artillery or fixed gun batteries in coastal fortifications.

From the Middle Ages until World War II, coastal artillery and naval artillery in the form of ...

, but Eisenhower viewed it as offering "a minimum of excitement" and preferred to become a civilian. The doctor then offered to recommend Eisenhower for a commission if he agreed not to seek appointment to the

Cavalry. Eisenhower intended to become an

Infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

officer, so he readily agreed. Because of the injury, West Point's academic board recommended against commissioning Eisenhower, but the doctor interceded successfully with the War Department and Eisenhower was commissioned as a

second lieutenant in September 1915.

Eisenhower requested to serve in the Insular Government of the

Philippine Islands

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, but was assigned to the

19th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

in

San Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

. While stationed there, Eisenhower served as the football coach for St. Louis College, now

St. Mary's University. He also met and married

Mamie Doud

Mary Geneva "Mamie" Eisenhower (; November 14, 1896 – November 1, 1979) was the first lady of the United States from 1953 to 1961 as the wife of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Born in Boone, Iowa, she was raised in a wealthy household in ...

, the daughter of a meat-processing facility owner from

Denver, Colorado

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

. Eisenhower performed security duties along the Mexican Border during the

Pancho Villa Expedition

The Pancho Villa Expedition—now known officially in the United States as the Mexican Expedition, but originally referred to as the "Punitive Expedition, U.S. Army"—was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the p ...

and received his first command assignment when he was chosen to lead the 19th Infantry's Company F.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

had broken out in Europe in 1914, and the U.S. joined the war on the side of the

Entente Powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

in April 1917. Like many 19th Infantry personnel, Eisenhower was promoted and assigned to the newly created

57th Infantry Regiment, where he served as the regimental supply officer. In September 1917, he was assigned to train reserve officers, first at

Fort Oglethrope and then at

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

.

In February 1918, he was transferred to

Camp Meade, Maryland

Fort George G. Meade is a United States Army installation located in Maryland, that includes the Defense Information School, the Defense Media Activity, the United States Army Field Band, and the headquarters of United States Cyber Command, the ...

, where he was assigned command of the 301st Heavy Tank Battalion. By the beginning of 1918, the United States Army did not have a single operational tank, but the battalion planned to use British-provided

Mark VI tank

The Mark VI was a British heavy tank project from the First World War.

Design

After having made plans for the continued development of the Mark I into the Mark IV, the Tank Supply Committee (the institute planning and controlling British tank ...

s after arriving in Europe. The 301st was initially scheduled to be deployed to Europe in early 1918, but in March 1918 the

tank corps

An armoured corps (also mechanized corps or tank corps) is a specialized military organization whose role is to conduct armoured warfare. The units belonging to an armoured corps include military staff, and are equipped with tanks and other armo ...

was established as an independent branch of the army, and Eisenhower's unit was assigned for further training at

Camp Colt

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

. After months of rudimentary training, the first tank, a

Renault FT

The Renault FT (frequently referred to in post-World War I literature as the FT-17, FT17, or similar) was a French light tank that was among the most revolutionary and influential tank designs in history. The FT was the first production tank to ...

, arrived in June 1918. In September, the "

Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case wa ...

" epidemic hit the camp, ultimately killing 175 of the roughly 10,000 men under his command. In October, Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and two weeks later he received orders to deploy to Europe. Shortly before the deployment, the war ended with the signing of the

Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

. Though Eisenhower and his tank crews never saw combat, he displayed excellent organizational skills, as well as an ability to accurately assess junior officers' strengths and make optimal placements of personnel. Despite his success as an organizer and trainer, during World War II rivals who had combat experience often sought to denigrate Eisenhower for his previous lack of combat experience.

Between wars

Tank warfare and transcontinental convoy, 1918–1921

With the end of World War I, the United States dramatically cut back military spending, and the number of active duty personnel in the army dropped from 2.4 million in late 1918 to about 150,000 in 1922. Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of

captain, but was almost immediately promoted to the rank of

major, the rank he held for the next sixteen years. Along with the rest of the tank corps, Eisenhower was assigned to

Fort George G. Meade

Fort George G. Meade is a United States Army installation located in Maryland, that includes the Defense Information School, the Defense Media Activity, the United States military bands#Army Field Band, United States Army Field Band, and the head ...

in Maryland. In 1919, he served on the

Transcontinental Motor Convoy

The Transcontinental Motor Convoys were early 20th century vehicle convoys, including three US Army truck trains, that crossed the United States (one was coast-to-coast) to the west coast. The 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy from Washington, ...

, an army vehicle exercise that traveled from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco at a pace of 5 mph. The convoy was designed both as a training event and as a way to publicize the need for better roads, and spurred many states to increase funding for road-building. Eisenhower's experience in the convoy would later influence his decision to help create the

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. T ...

in the 1950s.

He then returned to his duties at Camp Meade, serving as executive officer and then as commander of the 305th Tank Brigade, which fielded

Mark VIII tank

The Mark VIII tank also known as the Liberty or The International was a British-American tank design of the First World War intended to overcome the limitations of the earlier British designs and be a collaborative effort to equip France, the U ...

s. His new expertise in

tank warfare

Armoured warfare or armored warfare (mechanized forces, armoured forces or armored forces) (American English; see spelling differences), is the use of armored fighting vehicles in modern warfare. It is a major component of modern methods of ...

was strengthened by a close collaboration with

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

,

Sereno E. Brett, and other senior tank leaders; while Eisenhower commanded the 305th Tank Brigade, Patton commanded the 304th, which fielded the lighter

Renault FT

The Renault FT (frequently referred to in post-World War I literature as the FT-17, FT17, or similar) was a French light tank that was among the most revolutionary and influential tank designs in history. The FT was the first production tank to ...

tank and was also based at Camp Meade. Their leading-edge ideas of speed-oriented offensive tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors, who considered the new approach too radical and preferred to continue using tanks in a strictly supportive role for the infantry. After being threatened with a

court-martial by General

Charles S. Farnsworth, the chief of infantry, Eisenhower refrained from publishing theories that challenged existing tank doctrine. Although Secretary of War

Newton D. Baker and

Chief of Staff Peyton C. March both advocated for the continuation of the tank corps as an independent branch of the army, the

National Defense Act of 1920

The National Defense Act of 1920 (or Kahn Act) was sponsored by United States Representative Julius Kahn, Republican of California. This legislation updated the National Defense Act of 1916 to reorganize the United States Army and decentralize ...

folded the tank corps into the infantry. In 1921

Army Inspector General Eli Helmick found that Eisenhower had improperly received $250.76 in

housing allowance. Eisenhower claimed he had received the money with no intent to deceive, and he repaid it in full after Helmick made his finding. Helmick still pressed for a court-martial, and only the intervention of General

Fox Conner

Fox Conner (November 2, 1874 – October 13, 1951) was a Major general (United States), major general of the United States Army. He served as operations officer for the American Expeditionary Force during World War I, and is best remembered as a ...

, who told Pershing he wanted Eisenhower to serve as his executive officer in the

Panama Canal Zone, saved Eisenhower from possible imprisonment and dismissal from the service. Though Conner saved Eisenhower's career, Eisenhower still received a written reprimand that became part of his military record.

Service under Conner and Pershing, 1922–1929

Between 1922 and 1939, Eisenhower served under a succession of talented generals – Fox Conner,

John J. Pershing, and

Douglas MacArthur. Accompanied by Mamie, he served as General Conner's executive officer in Panama from 1922 to 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory, including the campaigns of

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, and

Carl von Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottfried (or Gottlieb) von Clausewitz (; 1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral", in modern terms meaning psychological, and political aspects of waging war. His mo ...

's ''

On War

''Vom Kriege'' () is a book on war and military strategy by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832. ...

''. Conner also shared his experiences working with the French and British during World War I, emphasizing the importance of the "art of persuasion" when dealing with allies. Eisenhower later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking, saying in 1962 that "Fox Conner was the ablest man I ever knew." Conner's comment on Eisenhower was, "

eis one of the most capable, efficient and loyal officers I have ever met." Conner would play a critical role in Eisenhower's career, often helping him gain choice assignments.

On Conner's recommendation,

and ranked in the top 10% of active-duty majors, in 1925–26 Eisenhower attended the

Command and General Staff College

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

(CGS) at

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

. He was worried that he would be disadvantaged by not having attended

Infantry School

A School of Infantry provides training in weapons and infantry tactics to infantrymen of a nation's military forces.

Schools of infantry include:

Australia

*Australian Army – School of Infantry, Lone Pine Barracks at Singleton, NSW.

France

...

like most of his classmates, but Conner assured him that his study in Panama was good preparation; Eisenhower graduated first in his CGS class of 245 officers. The army considered making him the head of the

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in al ...

program at a major university (Eisenhower would also have served as its football coach, doubling his pay) or a CGS faculty member, but assigned him as executive officer of the

24th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Benning, Georgia until 1927. Eisenhower disliked serving with the

Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo Soldiers originally were members of the 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, formed on September 21, 1866, at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This nickname was given to the Black Cavalry by Native American tribes who fought in t ...

regiment; many white officers viewed serving in an all-black unit as punishment for poor performance.

With Conner's help, Eisenhower was assigned to work under General Pershing on the

American Battle Monuments Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) is an independent agency of the United States government that administers, operates, and maintains permanent U.S. military cemeteries, memorials and monuments primarily outside the United States.

...

, which established monuments and cemeteries in Western Europe to honor fallen American soldiers. While serving on the commission, he produced ''A Guide to the American Battlefields in Europe'', a 282-page work which consisted largely of a history of the

American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

' battles on the

Western Front during World War I. He next attended the

Army War College, where he graduated first in his class in 1928. After graduating from the Army War College, he was reassigned to the American Battle Monuments Commission, arriving in

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

in August 1928. While in Europe, he learned to read (but not speak)

French, continued his study of World War I battles, and followed the contemporary politics of the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 19 ...

. In 1929, while helping General Pershing compile his memoirs, Eisenhower met Colonel

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

for the first time.

Service under Moseley and MacArthur, 1929–1939

In 1929, Eisenhower became the executive officer to General

George Van Horn Moseley

George Van Horn Moseley (September 28, 1874 – November 7, 1960) was a United States Army general. Following his retirement in 1938, he became controversial for his fiercely anti-immigrant and antisemitic views.

Early life and career

Moseley ...

, who served on the staff of

Assistant Secretary of War

The United States Assistant Secretary of War was the second–ranking official within the American Department of War from 1861 to 1867, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1890 to 1940. According to thMilitary Laws of the United States "The act of August 5 ...

Frederick Huff Payne

Frederick Huff Payne (November 10, 1876 – March 24, 1960) was the United States Assistant Secretary of War from 1930 to 1933, under President Herbert Hoover.

Biography

Payne was born on November 10, 1876 in Greenfield, Massachusetts to Samuel ...

. In this role, Eisenhower helped make national defense policy and studied wartime industrial mobilization and the relationship between government and industry. He formulated a 180-page mobilization plan, known as M-Day Plan, which was never utilized but which impressed his superiors. After Douglas MacArthur became army chief of staff, he assigned Moseley as Deputy Chief of Staff. Eisenhower officially remained on Moseley's staff, but he also worked as MacArthur's unofficial military secretary and served on the War Policies Commission, which studied the possibility of a constitutional amendment designed to clarify Congress's war-time powers. In 1932, he participated in MacArthur's violent clearing of the

Bonus March encampment in Washington, D.C. Eisenhower wrote and submitted MacArthur's official report regarding the incident, but he was privately critical of MacArthur's heavy-handed methods. President

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

was strongly criticized in the press for his administration's handling of Bonus March, even from papers that were normally sympathetic to his administration. In 1933, Eisenhower graduated from the Army Industrial College, which is now known as the

Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy.

In 1935, he accompanied MacArthur to the Philippines, where he was charged with developing the nascent

Philippine Army

The Philippine Army (PA) (Tagalog: ''Hukbong Katihan ng Pilipinas''; in literal English: ''Army of the Ground of the Philippines''; in literal Spanish: ''Ejército de la Tierra de la Filipinas'') is the main, oldest and largest branch of the ...

. Congress had passed the

Tydings–McDuffie Act

The Tydings–McDuffie Act, officially the Philippine Independence Act (), is an Act of Congress that established the process for the Philippines, then an American territory, to become an independent country after a ten-year transition period. ...

the previous year, setting the Philippines on the path to independence in 1946, and both MacArthur and Eisenhower remained on active duty in the U.S. army while serving as

military advisers to the Philippine government. Eisenhower declined the rank of brigadier general in the Philippine army, but was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the U.S. army in 1936. Eisenhower viewed the Philippine defense budget as inadequate, and he struggled to provide the army with modern weapons and sufficient training. He had strong philosophical disagreements with MacArthur regarding the role of the Philippine Army and the leadership qualities that an American army officer should exhibit and develop in his subordinates. The resulting antipathy between Eisenhower and MacArthur lasted the rest of their lives, though Eisenhower later emphasized that too much had been made of his disagreements with MacArthur. In his final official evaluation of Eisenhower, written during 1937, MacArthur wrote that Eisenhower was a "brilliant officer" who "in time of war ... should be promoted to General rank immediately." Historians have concluded that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the challenging personalities of

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, George S. Patton, George C. Marshall, and

Bernard Montgomery during World War II.

Eve of World War II, 1939–1941

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

invaded Poland in September 1939. By this time, Eisenhower had impressed his fellow officers with his administrative skills, but he had never held an active command above a brigade and few considered him a potential commander of major operations. Eisenhower returned to the United States in December 1939 and was assigned as commanding officer of 1st Battalion,

15th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Lewis. Eisenhower enjoyed his role as a commanding officer, writing later that his command of the 15th Infantry during maneuvers "fortified my conviction that I belonged with the troops; with them I was always happy." Eisenhower's time as commander of 1st Battalion was brief, because he was assigned as the regiment's executive officer. In June 1940, Congress promoted every officer in the army by one rank; Eisenhower officially became a

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

in March 1941. He hoped for a regimental command, but was disappointed when

Charles F. Thompson, commander of the

3rd Infantry Division, which was the 15th Infantry's higher headquarters, selected him to serve as the division's chief of staff. Eisenhower loyally acceded, and his success in the position was later viewed as one factor that caused the Army's senior leaders to identify Eisenhower as a candidate for positions of more rank and responsibility. General

Leonard T. Gerow asked Eisenhower to serve on his staff in the War Plans Division, but Eisenhower was determined to hold a command, and his ambivalent reply convinced Gerow to withdraw the request.

The army expanded from about 200,000 men in late 1939 to 1.4 million men in mid-1941. In March 1941, Eisenhower was assigned as chief of staff of the newly activated

IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

under Major General

Kenyon Joyce

Kenyon A. Joyce was a major general in the United States Army. He commanded the 1st Cavalry Division and later IX Corps in World War II.

Joyce was a prominent cavalry officer in the early outset of the war and was a mentor to a young George S. P ...

. In June 1941, he was appointed chief of staff to General

Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose fr ...

, Commander of the

Third Army at Fort Sam Houston. In mid-1941, the U.S. Army conducted the

Louisiana Maneuvers, the largest

military exercise that the army had ever conducted on U.S. soil. The

Second Army and the Third Army, which collectively had nearly 500,000 troops, conducted two mock battles that both ended in victory for the Third Army. The Third Army's success in the maneuvers impressed Eisenhower's superiors, and he was promoted to

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on October 3, 1941. Fellow officers predicted that he would become a major general in six months.

World War II

War Plans Division, 1941–1942

After the

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

in December 1941, the United States entered World War II. Almost immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor, General Marshall assigned Eisenhower as Deputy Chief of the War Plans Division in Washington. Marshall assigned him to coordinate the defense of the Philippines, and Eisenhower personally dispatched General

Patrick J. Hurley to Australia with $10 million to provide supplies to MacArthur. Biographer Jean Edward Smith writes that Marshall and Eisenhower developed a "father-son relationship"; it was widely assumed that Marshall would eventually lead major operations in Europe, and he initially sought to prepare Eisenhower to serve as his chief of staff during those operations. In February 1942, Eisenhower succeeded General Gerow as chief of the War Plans Division (later known as the Operations Division), and he was promoted to

major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

the following month, ''

Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' describing him as "one of the finest staff officers in the army".

Tasked with helping develop the army's grand strategy in the war, Eisenhower formulated a plan that centered on the build-up of U.S. forces in Britain, followed by an

invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity aggressively enter territory (country subdivision), territory owned by another such entity, gen ...

of Nazi-occupied Western Europe in April 1943. Eisenhower and Marshall both shared the conclusion of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

that the United States should pursue a

Europe first Europe first, also known as Germany first, was the key element of the grand strategy agreed upon by the United States and the United Kingdom during World War II. According to this policy, the United States and the United Kingdom would use the prepon ...

against the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. Though American and British leaders agreed to Eisenhower's proposed April 1943 invasion of Western Europe, competing priorities in other theaters of the war would repeatedly delay the invasion.

Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1943

Appointment in Europe

While assessing

Operation Bolero

Operation Bolero was the commonly used reference for the code name of the United States military troop buildup in the United Kingdom during World War II in preparation for the initial cross-channel invasion plan known as Operation Roundup, to be ...

, the build-up of Allied soldiers in Britain, Marshall and Eisenhower both came to the conclusion that General

James E. Chaney

James Eucene Chaney (March 16, 1885 – August 21, 1967) was a senior United States Army officer. He served in both World War I and World War II.

Early life

James Eucene Chaney was born in Chaneyville, Maryland. He studied at public schools ...

was unsuited to the task of leading American forces in Britain. Eisenhower recommended the appointment of a single American commander in the

European Theater of Operations (ETO), suggesting General

Joseph T. McNarney for the role. With the blessing of Stimson, Roosevelt, and Churchill, Marshall instead selected Eisenhower for the position, and Eisenhower was officially appointed as the commander of the ETO in June 1942; he was promoted to

lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

shortly thereafter.

Eisenhower retained Admiral

Harold Rainsford Stark

Harold Rainsford Stark (November 12, 1880 – August 20, 1972) was an officer in the United States Navy during World War I and World War II, who served as the 8th Chief of Naval Operations from August 1, 1939 to March 26, 1942.

Early life an ...

as the commander of U.S. naval forces in Europe, and selected General

Mark W. Clark

Mark Wayne Clark (May 1, 1896 – April 17, 1984) was a United States Army officer who saw service during World War I, World War II, and the Korean War. He was the youngest four-star general in the US Army during World War II.

During World War I ...

and General

Carl Spaatz as the respective commanders of U.S. ground troops and air forces in the theater. General

John C. H. Lee became the commander of the theater's logistical organization, and General

Walter Bedell Smith

General Walter Bedell "Beetle" Smith (5 October 1895 – 9 August 1961) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower's chief of staff at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) during the Tunisia Campai ...

became Eisenhower's chief of staff. His command involved important military and administrative duties, but one of his chief challenges was coordinating a multinational military and political alliance among combatants with contrasting military traditions and doctrines, as well a level of distrust. He also frequently met with the press and emerged as a public symbol of the Allied war effort.

Operation Torch

Overcoming objections from Eisenhower and Marshall, Prime Minister Churchill convinced Roosevelt that the Allies should delay an invasion of Western Europe and instead launch

Operation Torch, an invasion in North Africa. The U.S. and Britain had previously agreed to establish a

Combined Chiefs of Staff to serve as a unified command structure, and to appoint one individual as the commander of all

Allied forces in each

theater of war

In warfare, a theater or theatre is an area in which important military events occur or are in progress. A theater can include the entirety of the airspace, land and sea area that is or that may potentially become involved in war operations.

T ...

. Eisenhower became the commander of all Allied forces operating in the

Mediterranean Theater of Operations, making him the direct superior of both American and British officers.

The three-pronged Allied landing in North Africa, which biographer Jean Edward Smith describes as the "greatest amphibious operation that had ever been attempted" at that point in history, would take place on the Atlantic coast of

French Morocco and on the Mediterranean coast of

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. At the time, both Algeria and French Morocco were controlled by

Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its te ...

, an officially

neutral power that had been established in southern France following the French surrender to Germany in 1940. Vichy France had a complex relationship with the Allied Powers; it collaborated with Nazi Germany, but was recognized by the United States as the official government of France. Hoping to encourage French forces in Africa to support the Allied campaign, Eisenhower and diplomat

Robert Daniel Murphy

Robert Daniel Murphy (October 28, 1894 – January 9, 1978) was an American diplomat. He served as the first United States Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs when the position was established during the Eisenhower administration.

E ...

attempted to recruit General

Henri Giraud

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944.

Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from ...

, who lived in the Vichy-controlled part of France but was not part of its high command.

Eisenhower and Murphy were unable to gain Giraud's full support by the time of the landings, and French forces initially resisted the Allied landing. General

Alphonse Juin

Alphonse Pierre Juin (16 December 1888 – 27 January 1967) was a senior French Army general who became Marshal of France. A graduate of the École Spéciale Militaire class of 1912, he served in Morocco in 1914 in command of native troops. Upon ...

, the commander of Vichy forces in North Africa, quickly agreed to an armistice in

Algiers, but fighting continued at the other two landing spots. After it became clear that French forces in Africa would not accept Giraud as their commander, Murphy and General Clark negotiated an agreement with Admiral

François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service ...

, the commander-in-chief of Vichy armed forces, that granted the Allied Powers military access to French North Africa but confirmed French sovereignty over the region.

Though the agreement with Darlan provided for French cooperation in North Africa, Eisenhower was strongly criticized in the American and British press for his willingness to work with a Vichy official. Darlan was assassinated in December 1942 by Frenchman

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle (4 November 1922 – 26 December 1942) was a royalist member of the French resistance during World War II. He assassinated Admiral of the Fleet François Darlan, the former chief of government of Vichy France and t ...

, and Eisenhower appointed Giraud as the leader of French forces in Africa. Giraud would later become co-president of the

French Committee of National Liberation

The French Committee of National Liberation (french: Comité français de Libération nationale) was a provisional government of Free France formed by the French generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organi ...

(FCNL) alongside

Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

leader

Charles de Gaulle, but de Gaulle emerged as the clear leader of the organization, and the French war effort, by the end of 1943. Eisenhower, who had not actively supported either Giraud or de Gaulle after the initial campaign in French Africa, established a strong working relationship with de Gaulle for the remainder of the war.

Tunisia Campaign

Following the success of Operation Torch, the Allies launched an invasion of

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, which the Germans had taken control of during Operation Torch. Bolstered by superior tanks and air power, as well as favorable weather, the German forces established a strong defense of the city of

Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, leading to a stalemate in the campaign. The slow progress in Tunisia displeased many leading American and British officials, and General

Harold Alexander

Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis, (10 December 1891 – 16 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served with distinction in both the First and the Second World War and, afterwards, as Governor G ...

, the head of the British

Near East Command Near East Command was a Command of the British Armed Forces. It was only active from 1961 to 1962, but its subordinate Near East Land Forces was active from 1961 to as late as 1977.

History

In 1959 Middle East Command was divided into two command ...

, was appointed as Eisenhower's deputy commander. At the same time, Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of

general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

, making him the

twelfth four-star general in U.S. history. In February 1943, German forces launched a successful attack on General

Lloyd Fredendall

Lieutenant General Lloyd Ralston Fredendall (December 28, 1883 – October 4, 1963) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served during World War II. He is best known for his leadership failure during the Battle of Kasserine Pass ...

's

II Corps at the

Battle of Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a series of battles of the Tunisian campaign of World War II that took place in February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia.

The Axis forces, ...

. The II Corps collapsed and Eisenhower relieved Fredendall of command, but Allied forces prevented a German breakthrough. After the battle, the Allies continually built up their forces and slowly ground down German defenses. 250,000 Axis soldiers surrendered in May 1943, bringing an end to the

North African Campaign.

Italian Campaign

As the length of the Tunisia Campaign had made a cross-channel invasion of France impracticable in 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed that the next Allied target would be

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The July 1943

invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It bega ...

was overseen by Eisenhower and Alexander, with General

Bernard Montgomery and General George S. Patton each leading one of two simultaneous landings. Allied forces staged a successful landing, but they failed to prevent the retreat of a large portion of the German Army to mainland Italy. Shortly after the end of the campaign, Eisenhower severely reprimanded Patton after Patton

slapped two subordinates. Eisenhower refused to dismiss Patton in the midst of a public furor, though the slapping incidents may have played a role in his decision to recommend General

Omar Bradley

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893April 8, 1981) was a senior officer of the United States Army during and after World War II, rising to the rank of General of the Army. Bradley was the first chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and over ...

as the leader of preparations for the upcoming invasion of Western Europe.

During the campaign in Sicily, King

Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

Victor Emmanuel III (Vittorio Emanuele Ferdinando Maria Gennaro di Savoia; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. He also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia (1936–1941) and ...

arrested Prime Minister

Benito Mussolini and replaced him with

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, who secretly negotiated a surrender with the Allies. Germany responded by shifting several divisions to Italy, occupying

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, and establishing a

puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

, the

Italian Social Republic. The

Allied invasion of mainland Italy began in September 1943. In the aftermath of Italy's surrender, the Allies faced unexpectedly strong resistance from German forces under Field Marshal

Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' of the Luftwaffe during World War II who was subsequently convicted of war crimes. In a military career that spanned both world wars, Kesselring beca ...

, who nearly defeated

Operation Avalanche

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, but ...

, the Allied landing near the port of

Salerno. With 24 German divisions defending the country's rugged terrain, Italy quickly became a secondary theater in the war.

Operations in Western Europe, 1944–1945

Operation Overlord

In December 1943, President Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower—not Marshall—would lead

Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Western Europe. Roosevelt believed that Eisenhower's experience leading multinational and amphibious operations made him well qualified for the position, and he was unwilling to lose Marshall as chief of staff. Eisenhower retained Smith as his chief of staff, chose Air Chief Marshal Tedder as his deputy, and made Admiral

Bertram Ramsay and General John C. H. Lee the respective heads of naval operations and logistics in the theater. At the insistence of Churchill and the Combined Chiefs of Staff, he selected General Montgomery as commander of ground forces and Air Chief Marshal

Trafford Leigh-Mallory

Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, (11 July 1892 – 14 November 1944) was a senior commander in the Royal Air Force. Leigh-Mallory served as a Royal Flying Corps pilot and squadron commander during the First World War. Remaining in ...

as the commander of air forces in the theater. Prioritizing individuals with recent battle experience, he selected Bradley as the senior American field commander and General Spaatz as the head of the American strategic air force. Despite the earlier slapping incidents, Patton was chosen to command the

Third Army.

Eisenhower, as well as the officers and troops under him, had learned valuable lessons in their previous operations, preparing them for the most difficult campaign against the Germans—a beach landing assault in northern France. The starting point for the operation had been developed by a planning group led by General

Frederick E. Morgan; the plan called for a landing in

Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

rather than at

Pas-de-Calais, which was closer to Britain but was more heavily defended. Eisenhower and Montgomery jointly agreed to alter the plan in several ways, placing a greater emphasis on air superiority, increasing the number of soldiers committed to the operation, and establishing separate American and British landing zones across a wider area than had been originally envisioned. Eisenhower also helped secure de Gaulle's participation in the landing, partly by avoiding a diplomatic incident stemming from the arrest of several former Vichy officials who had assisted the Allies. Eisenhower believed that de Gaulle's cooperation was critical, not only for military operations but also for providing a government in France.

Drawing on the experience of Operation Avalanche, Eisenhower noted that it was "vital that the entire sum of our assault power, including the two Strategic Air Forces, be available for use during the critical stages of the attack." The final landing plan, largely devised by Montgomery, called for nine divisions to land at five zones. Three divisions of

airborne infantry

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in ai ...

would land behind the enemy lines in order to seize vital roads and bridges. Originally scheduled for May 1944, Operation Overlord was pushed back a month, largely due to landing craft shortages. For the same reason,

Operation Dragoon, the Allied landing in Southern France, would take place in August 1944 rather than contemporaneously with Overlord, as had originally been planned. Eisenhower insisted that the British give him exclusive command over all strategic air forces to facilitate the landing, to the point of threatening to resign unless Churchill relented, which he did.

High winds delayed Operation Overlord by a day, but Eisenhower chose to take advantage of a break in the weather and ordered the

Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and ...

to take place on June 6, 1944. The timing and location of the landings surprised the Germans, and they failed to reinforce the beachheads in a timely manner. Allied forces quickly secured four of the five landing zones, though the Germans put up a strong defense of

Omaha Beach. The Allies consolidated control of the landing zones and launched the next phase of the operation,

capturing the port of

Cherbourg by the end of June. By the end of July, over 1.5 million Allied soldiers and over 300,000 vehicles had landed in Normandy. The Allies repulsed a German counter-attack at the

Battle of the Falaise Pocket, bringing a close to the fighting in Normandy. Meanwhile, the Operation Dragoon landings were successful, as the Allies captured

Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

and began moving north. On the

Eastern Front, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

launched a major offensive known as

Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration (; russian: Операция Багратио́н, Operatsiya Bagration) was the codename for the 1944 Soviet Byelorussian strategic offensive operation (russian: Белорусская наступательная оп ...

, preventing Germany from sending reinforcements west.

Liberation of France and invasion of Germany

Once the coastal assault had succeeded, Eisenhower insisted on retaining personal control over the land battle strategy, and was immersed in the command and supply of multiple assaults. Encouraged by de Gaulle and the German commander

Dietrich von Choltitz, Eisenhower ordered the

liberation of Paris in late August. Von Cholitz surrendered the city on August 25, and de Gaulle triumphantly entered the city the following day. With German resistance collapsing sooner than had been expected, the Allies rapidly liberated most of France,

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and

Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

. General Montgomery proposed an assault through Germany's

Ruhr region, while General Bradley called for an attack further south into the

Saar

Saar or SAAR has several meanings:

People Given name

*Saar Boubacar (born 1951), Senegalese professional football player

* Saar Ganor, Israeli archaeologist

*Saar Klein (born 1967), American film editor

Surname

* Ain Saar (born 1968), Est ...

region; Eisenhower approved both operations. Eisenhower's decision to split up Allied forces and advance on a broad front strained logistics and gave the Germans time to retreat to more defensible positions closer to Germany.

In recognition of his senior position in the Allied command, on December 20, 1944, he was promoted to

General of the Army, equivalent to the rank of

field marshal in most European armies. That same month, the Germans launched a surprise counter offensive, the

Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

, which the Allies turned back in early 1945 after Eisenhower repositioned his armies and after improved weather allowed the Air Force to engage. Though many Allied soldiers lost their lives in the fighting, Germany suffered a decisive defeat in the battle.

After the Battle of the Bulge and the success of a massive Soviet offensive in early 1945, Eisenhower sent Air Chief Marshal Tedder to the Soviet Union to help establish a joint strategy for the

invasion of Germany. Eisenhower declined to engage the Soviets in a race for the German capital of

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, and instead prioritized linking up with Soviet forces as soon as possible. Allied soldiers reached the

Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

in early March,

capturing a key bridge near the town of

Remagen

Remagen ( ) is a town in Germany in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, in the district of Ahrweiler. It is about a one-hour drive from Cologne, just south of Bonn, the former West German capital. It is situated on the left (western) bank of the ...

before the Germans could destroy it. German resistance quickly collapsed, and on May 7, Eisenhower accepted the

surrender of Germany

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the "Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capit ...

.

Postwar military service

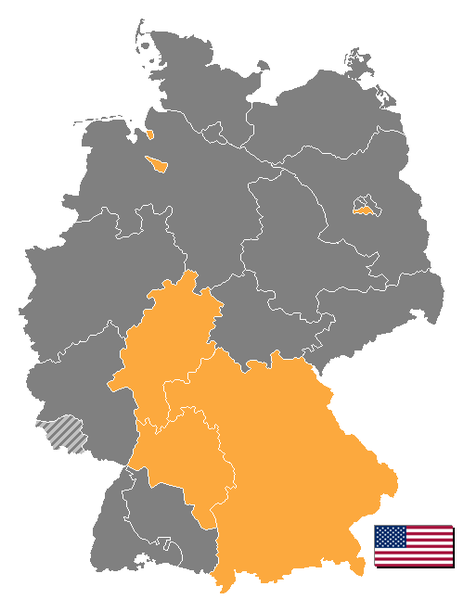

Occupation zone commander, 1945

Eisenhower, Montgomery, Soviet Marshal

Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

, and French General

Jean de Lattre de Tassigny met on June 5, 1945, agreeing to establish the

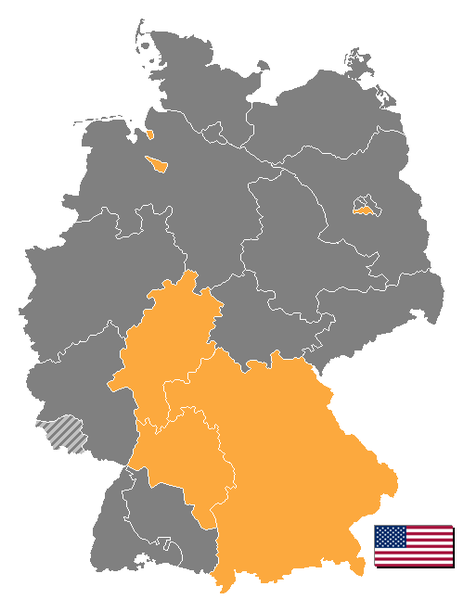

Allied Control Council, which provided for the joint governance of Germany by the four powers. Eisenhower became the military governor of the

American occupation zone

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

, located primarily in

Southern Germany

Southern Germany () is a region of Germany which has no exact boundary, but is generally taken to include the areas in which Upper German dialects are spoken, historically the stem duchies of Bavaria and Swabia or, in a modern context, Bavaria ...

and

headquartered

Headquarters (commonly referred to as HQ) denotes the location where most, if not all, of the important functions of an organization are coordinated. In the United States, the corporate headquarters represents the entity at the center or the top ...

at the

IG Farben Building

The IG Farben Building – also known as the Poelzig Building and the Abrams Building, formerly informally called The Pentagon of Europe – is a building complex in Frankfurt, Germany, which currently serves as the main structure of the West ...

in

Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , "Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its na ...

. In September 1945, Eisenhower removed General Patton from his command in

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

after the latter publicly expressed opposition to

denazification. The removal of Patton sent a strong signal to that official policies regarding denazification would be strictly observed. Though Eisenhower aggressively purged ex-Nazis, his actions largely reflected the American attitude that the broad German populace were victims of the Nazis.

In response to the devastation in Germany, including food shortages and an influx of refugees, he arranged distribution of American food and medical equipment. Upon discovery of the

Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

, he ordered camera crews to document evidence of the atrocities in them for use in the

Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

. He reclassified German

prisoners of war (POWs) in U.S. custody as

Disarmed Enemy Forces

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF, less commonly, Surrendered Enemy Forces) was a US designation for soldiers who surrendered to an adversary after hostilities ended, and for those POWs who had already surrendered and were held in camps in occupied Ge ...

(DEFs), who were no longer subject to the Geneva Convention. He also developed a strong working relationship with Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the commander of the

Soviet occupation zone

The Soviet Occupation Zone ( or german: Ostzone, label=none, "East Zone"; , ''Sovetskaya okkupatsionnaya zona Germanii'', "Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany") was an area of Germany in Central Europe that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a ...

in Germany. At Zhukov's request, he visited

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, where he observed Russian culture and met with Soviet leader

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

. Eisenhower learned of the secret

development of the atomic bomb weeks before the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; he expressed opposition to the bombings on the grounds that the use of atomic weaponry would increase post-war tensions.

Army Chief of Staff, 1945–1948

Following the end of the World War II, Marshall retired in November 1945. On Marshall's recommendation, President Truman selected Eisenhower as the new Chief of Staff of the Army. His main task in that role was the demobilization of millions of soldiers, but he also advised the president on military policy and made numerous public appearances in order to maintain public support for the army. Concerned that rapid demobilization would deprive the army of necessary manpower in its duties and fully return the military to its small, pre-war state, Eisenhower joined Truman in calling for some form of universal military service. Congress rejected the idea of universal service, though it did extend the

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940

The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, also known as the Burke–Wadsworth Act, , was the first peacetime conscription in United States history. This Selective Service Act required that men who had reached their 21st birthday b ...

.

Eisenhower was convinced in 1946 that the Soviet Union did not want war and that friendly relations could be maintained; he strongly supported the new

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

and favored its involvement in the control of atomic bombs. However, in formulating policies regarding the atomic bomb and relations with the Soviets, the administration of President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

largely ignored senior military leaders in favor of the State Department. By mid-1947, as East–West tensions over economic recovery in Germany and the

Greek Civil War

The Greek Civil War ( el, ο Eμφύλιος �όλεμος}, ''o Emfýlios'' 'Pólemos'' "the Civil War") took place from 1946 to 1949. It was mainly fought against the established Kingdom of Greece, which was supported by the United Kingdom and ...

escalated, Eisenhower had come to agree with the

containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which wa ...

policy of stopping Soviet expansion. Increasingly frustrated with his position of chief of staff, in 1948, he became the president of

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, an

Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight school ...

university in New York City. Nonetheless, he continued to advise the military on various matters. During his time at Columbia, he published his memoirs, which were titled ''

Crusade in Europe

''Crusade in Europe'' is a book of wartime memoirs by General Dwight D. Eisenhower published by Doubleday in 1948. Maps were provided by Rafael Palacios.

''Crusade in Europe'' is a personal account by one of the senior military figures of Wo ...

''.