Michael Doheny on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

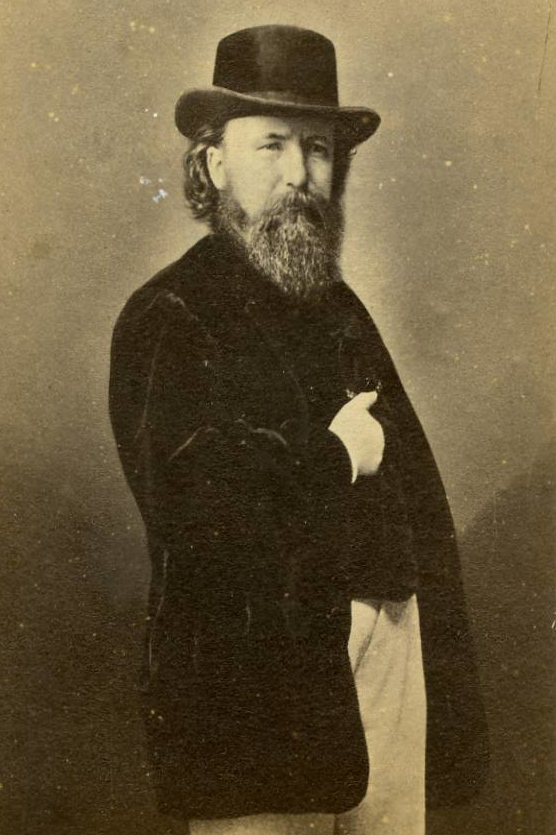

Michael Doheny (22 May 1805 – 1 April 1862Some references give 1862: ) was an Irish writer, lawyer, member of the

In 1830 Doheny acted as an election "warden" in the successful campaign of Thomas Wyse to become an MP for Tipperary. It was through Wyse's people that Doheny became involved in the

In 1830 Doheny acted as an election "warden" in the successful campaign of Thomas Wyse to become an MP for Tipperary. It was through Wyse's people that Doheny became involved in the

During the summer of 1847, Doheny began setting up "Confederate Clubs" around Tipperary as well as helping

During the summer of 1847, Doheny began setting up "Confederate Clubs" around Tipperary as well as helping

Upon immigrating to the

Upon immigrating to the

Text at Project Gutenberg

New York, 1867, and of two poems, "Achusha gal machree" and "The Outlaw's Wife."

Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

movement, and co-founder of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

, an Irish secret society which would go on to launch the Fenian Raids on Canada, Fenian Rising of 1867

The Fenian Rising of 1867 ( ga, Éirí Amach na bhFíníní, 1867, ) was a rebellion against British rule in Ireland, organised by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

After the suppression of the ''Irish People'' newspaper in September 1865 ...

and the Easter Rising of 1916, each of which was an attempt to bring about Irish Independence from Britain.

Early life

The third son of small farmer Michael Doheny, he was born at Brookhill, near Fethard, Co. Tipperary. Growing up he received a rudimentary education from an itinerant teacher while working on his father's farm. He would continue his formal education into his adult life while simultaneously acting as a teacher himself to local children. Doheny's ambition was to receive a formal legal education so that he could become a lawyer capable of seeking redress for members of his community, who were generally poor. Doheny's parents both died in quick succession during his teens, leaving Doheny's eldest brother, himself only in his teenage years, as head of the household. Doheny himself had to fight through a bout oftyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure. ...

at the age of 14. As Doheny became 20, his eldest brother also died and the family farm came into his procession. He subsequently sold it and continued to focus on his education.

Doheny was admitted to Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and W ...

in November 1834 and King's Inns

The Honorable Society of King's Inns ( ir, Cumann Onórach Óstaí an Rí) is the "Inn of Court" for the Bar of Ireland. Established in 1541, King's Inns is Ireland's oldest school of law and one of Ireland's significant historical environment ...

in 1835 before being called to the Irish bar in 1838. Doheny would set up business in Cashel, County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early 13th century, shortly after ...

, and would be appointed legal assessor to the borough of Cashel under the Municipal Corporations Act of 1840. This allowed him to successfully prosecute former borough officers for corruption such as misappropriation of funds and fraudulent transfers of property, which won Doheny wider acclaim.

Entering politics

In 1830 Doheny acted as an election "warden" in the successful campaign of Thomas Wyse to become an MP for Tipperary. It was through Wyse's people that Doheny became involved in the

In 1830 Doheny acted as an election "warden" in the successful campaign of Thomas Wyse to become an MP for Tipperary. It was through Wyse's people that Doheny became involved in the Repeal Association

The Repeal Association was an Irish mass membership political movement set up by Daniel O'Connell in 1830 to campaign for a repeal of the Acts of Union of 1800 between Great Britain and Ireland.

The Association's aim was to revert Ireland to th ...

. The Repeal Association was part of the movement in Ireland which sought to repeal the Act of Union, which had dissolved the Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland ( ga, Parlaimint na hÉireann) was the legislature of the Lordship of Ireland, and later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1297 until 1800. It was modelled on the Parliament of England and from 1537 comprised two ch ...

. It was in 1841 that he formally joined Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

's Repeal Association. In May 1841, Doheny was placed on the association's general committee. O'Connell found Doheny difficult to control and was unsettled by Doheny's queries into the association's financial management.

By 1842 Doheny had established himself as a successor lawyer in and around Cashel. It was in that year he married Mary Jane O'Dwyer, with whom he moved into a new house in Cashel alongside Mary Jane's mother. In the years to come Michael and Mary Jane would have four children together; Morgan, Michael, Edmond and Jane Doheny.

It was also in 1842 that Doheny began to associate with the more militant members of the repeal movement such as Thomas Davis. There was a divide in both age and class between the rural Doheny and the Davis' clique, many of whom looked down upon Doheny. Others, however, acknowledged him for his passion, with one of his colleagues anonymously remarked of Doheny that he was "rough, generous, bold, a son of the soil, slovenly in dress, red-haired and red-featured, but a true personification of the hopes, passions, and traditions of the people". Doheny assisted in the launch of The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

, a newspaper that served as an outlet for Young Irelander thoughts. Doheny was quickly annoyed when a significant number of his article were rejected by the editors. It was also around this period that Doheny published ''History of the American Revolution'' in the pages of the Nation.

It has been suggested by historians James Quinn and Desmond McCabe that Doheny may have been a better orator than a writer, and that he excelled more so during public meetings of the repeal movement around Tipperary and in Dublin. Viewing the large crowds who would come to attend these "monster" meetings in 1843, Doheny became to believe there was a military potential in these same people. Doheny would later claim that, alongside Thomas Davis and John Blake Dillon, he deliberately ran repeal meetings with military undertones in order to prepare the Irish peasantry for a future war with the British, however, historians have doubted the credibility of that claim and suggested it is a revisionist claim.

In 1845 Doheny was asked by the Repeal Association to use his legal knowledge to investigate if Irish Members of Parliament had the legal right to withdraw from the House of Commons (" Abstentionism"). Doheny reluctantly submitted that, in his legal opinion, that this course of action could result in legal action being taken against MPs who did so. This was not the answer that Daniel O'Connell wanted to hear and led to a souring of the relationship between the two. Tensions continued to mount between the two when O'Connell took offence to Doheny's view that University education in Ireland should be of a secular/non-denominational nature during public debates over the Maynooth College Act 1845

The Maynooth College Act 1845 (8 & 9 Vict. c. 25) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

St Patrick's College, Maynooth was established by the Maynooth College Act 1795 as a seminary for Ireland's Catholic priests. The British gove ...

. It was also in 1845 that a parliamentary seat became vacant in Tipperary. Doheny by now would have been a good candidate to stand for that seat, however, he was passed over for the selection by O'Connell's Repeal party.

In April 1846 William Smith O'Brien

William Smith O'Brien ( ga, Liam Mac Gabhann Ó Briain; 17 October 1803 – 18 June 1864) was an Irish nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) and a leader of the Young Ireland movement. He also encouraged the use of the Irish language. He ...

was imprisoned for a month for refusing to serve on a parliamentary committee. The controversy resulted in a stark split amongst the emerging Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

movement and O'Connell's Repealers. Doheny and the Younger Ireland backed O'Brien's conduct and became to voice their more radical views. The two groups formally split in July 1846, and Doheny was one of the hardliners who resisted any attempts at reconciliation. Subsequently, Doheny was one of the co-founders of the Irish Confederation

The Irish Confederation was an Irish nationalist independence movement, established on 13 January 1847 by members of the Young Ireland movement who had seceded from Daniel O'Connell's Repeal Association. Historian T. W. Moody described it as "t ...

on 13 January 1847.

Rebellion of 1848

During the summer of 1847, Doheny began setting up "Confederate Clubs" around Tipperary as well as helping

During the summer of 1847, Doheny began setting up "Confederate Clubs" around Tipperary as well as helping James Fintan Lalor

James Fintan Lalor (in Irish, Séamas Fionntán Ó Leathlobhair) (10 March 1809 – 27 December 1849) was an Irish revolutionary, journalist, and “one of the most powerful writers of his day.” A leading member of the Irish Confederation (You ...

's attempt to setup a tenant's league branch in Holycross

Holycross () is a village and civil parish in County Tipperary, Ireland. It is one of 21 civil parishes in the barony of Eliogarty. The civil parish straddles two counties and the baronies of Eliogarty and of Middle Third (South Tipperary). It ...

.

Doheny was amongst a small amount of Young Irelanders attracted to Lalor's revolutionary agrarian philosophy, however, he supported Smith O'Brien over John Mitchel

John Mitchel ( ga, Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist. In the Famine years of the 1840s he was a leading writer for ''The Nation'' newspaper produced by the ...

in January 1848 when Mitchel called for revolution. Doheny's position changed after Mitchel was convicted for treason felony

The Treason Felony Act 1848 (11 & 12 Vict. c. 12) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Parts of the Act are still in force. It is a law which protects the King and the Crown.

The offences in the Act w ...

in May, with Doheny now prepared to support an outright rebellion. In turn Doheny was arrested for seditious speechmaking on 12 July in Cashel. He was bailed out on 20 July, just 9 days before the beginning of the Young Ireland rebellion. Doheny's attempts to raise men up in Tipperary but his efforts were held back by William Smith O'Brien's indecisiveness.

After action in Ballingarry on 31 July fell apart, Doheny fled to the Mountain of Slievenamon

Slievenamon or Slievenaman ( ga, Sliabh na mBan , "mountain of the women") is a mountain with a height of in County Tipperary, Ireland. It rises from a plain that includes the towns of Fethard, Clonmel and Carrick-on-Suir. The mountain is stee ...

. For the next two months Doheny evaded the authorities alongside James Stephens all across Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following t ...

. Doheny eventually escaped Ireland by dressing as a priest and boarding a cattle ship travelling from Cork to Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

. From there Doheny immediately proceeded to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he reunited with Stephens. The two were joined by fellow rebel John O'Mahony

John Francis O'Mahony (1815 – 7 February 1877) was a Gaelic scholar and the founding member of the Fenian Brotherhood in the United States, sister organisation to the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Despite coming from a reasonably wealthy fa ...

. The trio remained in Paris for two months before departing for New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Life in the US

Upon immigrating to the

Upon immigrating to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, Doheny returned to practising law in order to support himself. However, he remained active in Irish Republican circles, of which there was no shortage in the city as it swelled with other Young Irelander exiles. There were tensions amongst the conservative and radical Young Irelanders in New York, exemplified by an incident involving Doheny and Thomas D'Arcy McGee

Thomas D'Arcy McGee (13 April 18257 April 1868) was an Irish-Canadian politician, Catholic spokesman, journalist, poet, and a Father of Canadian Confederation. The young McGee was an Irish Catholic who opposed British rule in Ireland, and w ...

. Accounts of the incident vary. One version suggests that McGee accused Doheny of boasting, drunkenness, and incompetence and in response, Doheny attempted to push McGee down an open cellar on the street they were walking. Historians James Quinn and Desmond McCabe note that John Blake Dillon made similar accusations against Doheny, and therefore they may not have been without foundation. Another account of the altercation between Doheny and McGee suggests that Doheny challenged McGee to a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the rapier and ...

, but McGee refused. Enraged, Doheny assaulted McGee. Apparently, McGee was arrested but not charged with a crime.

Unfortunately for Doheny, this was not the only violent altercation he was involved in during this first year in America. Doheny was involved in a public debate over the policies of Daniel O'Connell with O'Connell loyalist Patrick H. O’Conner. After the event, Doheny and O'Conner confronted each other in the street and got into a fistfight. A duel between the two was arranged, but supposedly on the day it was due to occur, O'Conner departed for Ireland.

In 1849 Doheny wrote the book ''The Felon's track'', which recounted in a very critical way the history of the repeal movement and the 1848 rebellion. Doheny was particularly critical of O'Connell's involvement. The book was quite successful and reprinted several times. In turn, Doheny became in demand as a speaker at Irish-American societies. Doheny also contributed a memoir on Geoffrey Keating

Geoffrey Keating ( ga, Seathrún Céitinn; c. 1569 – c. 1644) was a 17th-century historian. He was born in County Tipperary, Ireland, and is buried in Tubrid Graveyard in the parish of Ballylooby-Duhill. He became an Irish Catholic priest and a ...

, a 17th-century Irish historian from Doheny's native Tipperary, to John O'Mahony's translation of ''Foras Feasa ar Éirinn'', which O'Mahony was working on for several years.

Right from his initial arrival in New York, Doheny had become involved in the city's Irish-centric militias. In November 1851 Doheny was elected as Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment, and in September 1852 he became Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

of a new regiment the Irish Republican Rifles. These Irish controlled militias generally had Irish Independence as an objective but were often fraught with infighting over strategy and leadership battles.

In February 1856, Doheny and O'Mahony founded the Emmet Monument Association

The Emmet Monument Association (EMA) was a mid-nineteenth century secret military organization with the special purpose of training men to attack England and free Ireland. It was established in the mid-1850s, by John O'Mahony and Michael Dohen ...

, an organisation with the publicly stated goal of funding a monument to Irish rebel leader Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Prote ...

, but with the private goal of unifying Irish Republicans in America under one banner. Upon the outbreak of the Crimea War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

in March 1857, Doheny and O'Mahony met with the Russian consul in New York and sought to secure backing for another rebellion in Ireland from the Russian Empire. They presented the consul with a request from the various Irish militias for transport to Ireland for 2,000 men and arms for another 5,000. The request was sent back to Russia where supposedly there was some interest in the plan, however, ultimately the plot was considered unaffordable by the Russians. The failure to secure the backing of the Russians is suggested to have demoralised many of the Irish-American organisations, even causing some of them to fall apart.

Doheny and O'Mahony, responding to the fragmentation occurring, reached out to James Stephens in the autumn of 1857. Stephens agreed to aid them, but in return asked for undisputed leadership of any proposed grouping. Stephens had just founded the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

on 17 March 1858, and in turn, Doheny and O'Mahoney agreed to organise its American counterpart the Fenian Brotherhood

The Fenian Brotherhood () was an Irish republican organisation founded in the United States in 1858 by John O'Mahony and Michael Doheny. It was a precursor to Clan na Gael, a sister organisation to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). M ...

in early 1859. Simultaneously Doheny founded the short-lived newspaper ''the Phoenix'' to spread the ideals of the new Fenian movement.

Doheny was involved in the funeral arrangements for Terence Bellew MacManus in Ireland and acted as one of his pallbearers in a New York ceremony. Doheny travelled to Ireland in October 1861 to accompany the body home, where his spirits were lifted by the large crowds who came out not only to honour MacManus' body, but who cheered for "Colonel" Doheny. Doheny's morale was high for the enthusiasm he saw that he began to argue again for another rebellion in Ireland, but this line of thinking was overruled by James Stephens. After the funeral, Doheny made an emotional visit to Cashel in Tipperary where he was given a hero's welcome.

Death

Not long after the McManus funeral, Doheny himself died suddenly on 1 April 1862. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery inQueens, New York

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

.

Works

Doheny is best known as author of a small work, ''The Felon's Track,''Text at Project Gutenberg

New York, 1867, and of two poems, "Achusha gal machree" and "The Outlaw's Wife."

References

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Doheny, Michael 1805 births 1862 deaths Irish poets Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood People from County Tipperary Young Irelanders 19th-century poets