Mexican War for Independence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in

, Monografias, 1996; accessed 21 December 2018. This ephemeral Catholic monarchy was overthrown and a

Immediately after the Mexico City coup ousting Iturrigaray, juntas in Spain created the Supreme Central Junta of Spain and the Indies, on 25 September 1808 in Aranjuez. Its creation was a major step in the political development in the Spanish empire, once it became clear that there needed to be a central governing body rather than scattered juntas of particular regions. Joseph I of Spain had invited representatives from Spanish America to

Immediately after the Mexico City coup ousting Iturrigaray, juntas in Spain created the Supreme Central Junta of Spain and the Indies, on 25 September 1808 in Aranjuez. Its creation was a major step in the political development in the Spanish empire, once it became clear that there needed to be a central governing body rather than scattered juntas of particular regions. Joseph I of Spain had invited representatives from Spanish America to

From a small gathering at the Dolores church, other joined the rising including workers on local landed estates, prisoners liberated from jail, and a few members of a royal army regiment. Many estate workers' weapons were agricultural tools now to be used against the regime. Some were mounted and acted as a cavalry under the direction of their estate foremen. Others were poorly armed Indians with bows and arrows. The numbers joining the revolt rapidly swelled under Hidalgo's leadership, they began moving beyond the village of Dolores. Despite rising tensions following the events of 1808, the royal regime was largely unprepared for the suddenness, size, and violence of the movement.

From a small gathering at the Dolores church, other joined the rising including workers on local landed estates, prisoners liberated from jail, and a few members of a royal army regiment. Many estate workers' weapons were agricultural tools now to be used against the regime. Some were mounted and acted as a cavalry under the direction of their estate foremen. Others were poorly armed Indians with bows and arrows. The numbers joining the revolt rapidly swelled under Hidalgo's leadership, they began moving beyond the village of Dolores. Despite rising tensions following the events of 1808, the royal regime was largely unprepared for the suddenness, size, and violence of the movement.

The religious character of the movement was present from the beginning, embodied in leadership of the priest, Hidalgo. The movement's banner with image of the

The religious character of the movement was present from the beginning, embodied in leadership of the priest, Hidalgo. The movement's banner with image of the  The new viceroy quickly organized a defense, sending out the Spanish general Torcuato Trujillo with 1,000 men, 400 horsemen, and two cannons – all that could be found on such short notice. The crown had established a standing military in the late eighteenth century, granting non-Spaniards who served the ''fuero militar'', the only special privileges for mixed-race men were eligible. Indians were excluded from the military. Royal army troops of the professional army were supplemented by local militias. The regime was determined to crush the uprising and attempted to stifle malcontents who might be drawn to the insurgency.

The new viceroy quickly organized a defense, sending out the Spanish general Torcuato Trujillo with 1,000 men, 400 horsemen, and two cannons – all that could be found on such short notice. The crown had established a standing military in the late eighteenth century, granting non-Spaniards who served the ''fuero militar'', the only special privileges for mixed-race men were eligible. Indians were excluded from the military. Royal army troops of the professional army were supplemented by local militias. The regime was determined to crush the uprising and attempted to stifle malcontents who might be drawn to the insurgency.

Despite apparently having the advantage, Hidalgo retreated, against the counsel of Allende. This retreat, on the verge of apparent victory, has puzzled historians and biographers ever since. They generally believe that Hidalgo wanted to spare the numerous Mexican citizens in Mexico City from the inevitable sacking and plunder that would have ensued. His retreat is considered Hidalgo's greatest tactical error and his failure to act "was the beginning of his downfall." Hidalgo moved west and set up headquarters in

Despite apparently having the advantage, Hidalgo retreated, against the counsel of Allende. This retreat, on the verge of apparent victory, has puzzled historians and biographers ever since. They generally believe that Hidalgo wanted to spare the numerous Mexican citizens in Mexico City from the inevitable sacking and plunder that would have ensued. His retreat is considered Hidalgo's greatest tactical error and his failure to act "was the beginning of his downfall." Hidalgo moved west and set up headquarters in

Warfare in the northern Bajío region waned after the capture and execution of the insurgency's creole leadership, but the insurgency had already spread to other more southern regions, to the towns of Zitácuaro, Cuautla, Antequera (now Oaxaca) towns where a new leadership had emerged. Priests

Warfare in the northern Bajío region waned after the capture and execution of the insurgency's creole leadership, but the insurgency had already spread to other more southern regions, to the towns of Zitácuaro, Cuautla, Antequera (now Oaxaca) towns where a new leadership had emerged. Priests

With the execution of Morelos in 1815, Vicente Guerrero emerged as the most important leader of the insurgency. From 1815 to 1821 most of the fighting for independence from Spain was by guerrilla forces in the ''tierra caliente'' (hot country) of southern Mexico and to a certain extent in northern New Spain. In 1816,

With the execution of Morelos in 1815, Vicente Guerrero emerged as the most important leader of the insurgency. From 1815 to 1821 most of the fighting for independence from Spain was by guerrilla forces in the ''tierra caliente'' (hot country) of southern Mexico and to a certain extent in northern New Spain. In 1816,

Iturbide's assignment to the Oaxaca expedition in 1820 coincided with a successful military coup in Spain against the monarchy of Ferdinand VII. The coup leaders, part of an expeditionary force assembled to suppress the independence movements in the Americas, had turned against the autocratic monarchy. They compelled the reluctant Ferdinand to reinstate the liberal

Iturbide's assignment to the Oaxaca expedition in 1820 coincided with a successful military coup in Spain against the monarchy of Ferdinand VII. The coup leaders, part of an expeditionary force assembled to suppress the independence movements in the Americas, had turned against the autocratic monarchy. They compelled the reluctant Ferdinand to reinstate the liberal  With the situation changed in part because of the Spanish Constitution, Guerrero realized that creole elites might move toward independence and exclude the insurgents. For that reason, his reaching an accommodation with the royalist army became a pragmatic move. From the royalist point of view, forging an alliance with their former foes created a way forward to independence. If creoles had declared independence for their own political purposes without coming to terms with the insurgency in the south, then an independent Mexico would have to contend with rebels who could threaten a new nation. Iturbide initiated contact with Guerrero in January 1821, indicating he was weighing whether to abandon the royalist cause. Guerrero was receptive to listening to Iturbide's vague proposal, but was not going to commit without further clarification. Iturbide replied to Guerrero's demand for clarity, saying that he had a plan for a constitution, one apparently based on the 1812 Spanish liberal constitution. Guerrero responded that the failure of that constitution to address the grievances of many in New Spain, and particularly objected to that constitution's exclusion of

With the situation changed in part because of the Spanish Constitution, Guerrero realized that creole elites might move toward independence and exclude the insurgents. For that reason, his reaching an accommodation with the royalist army became a pragmatic move. From the royalist point of view, forging an alliance with their former foes created a way forward to independence. If creoles had declared independence for their own political purposes without coming to terms with the insurgency in the south, then an independent Mexico would have to contend with rebels who could threaten a new nation. Iturbide initiated contact with Guerrero in January 1821, indicating he was weighing whether to abandon the royalist cause. Guerrero was receptive to listening to Iturbide's vague proposal, but was not going to commit without further clarification. Iturbide replied to Guerrero's demand for clarity, saying that he had a plan for a constitution, one apparently based on the 1812 Spanish liberal constitution. Guerrero responded that the failure of that constitution to address the grievances of many in New Spain, and particularly objected to that constitution's exclusion of

Iturbide persuaded royalist officers to change sides and support independence as well as the mixed-race old insurgent forces. For some royalist commanders, their forces simply left, some of them amnestied former insurgents. The high military command in Mexico City deposed the viceroy, Juan Ruiz de Apodaca in July 1821, replacing him with an interim viceroy, royalist general Francisco Novella. By the time that the new viceroy

Iturbide persuaded royalist officers to change sides and support independence as well as the mixed-race old insurgent forces. For some royalist commanders, their forces simply left, some of them amnestied former insurgents. The high military command in Mexico City deposed the viceroy, Juan Ruiz de Apodaca in July 1821, replacing him with an interim viceroy, royalist general Francisco Novella. By the time that the new viceroy

In 1910, as part of the celebrations marking the centennial of the Hidalgo revolt of 1810, President

In 1910, as part of the celebrations marking the centennial of the Hidalgo revolt of 1810, President "Historiadores se reunen con miras al bicentenario de la consumación de la independencia en 2021". INAH, Gobierno de México.2019/09/10

accessed 20 March 2020

Chieftains of Mexican IndependenceImage of women participating in Mexican Independence Day celebrations, Los Angeles, 1935.

Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. {{Authority control

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

's independence from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional struggles that occurred within the same period, and can be considered a revolutionary civil war.

Independence was not an inevitable outcome, but events in Spain directly impacted the outbreak of the armed insurgency in 1810 and its course until 1821. Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

Bonaparte's invasion of Spain in 1808 touched off a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule, since he had placed his brother Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

on the Spanish throne after forcing the abdication of the Spanish monarch Charles IV. In Spain and many of its overseas possessions, the local response was to set up juntas ruling in the name of the Bourbon monarchy

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanish ...

. Delegates in Spain and overseas territories met in Cádiz, Spain, still under Spanish control, as the Cortes of Cádiz

The Cortes of Cádiz was a revival of the traditional '' cortes'' (Spanish parliament), which as an institution had not functioned for many years, but it met as a single body, rather than divided into estates as with previous ones.

The Genera ...

, and drafted the Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

. That constitution sought to create a new governing framework in the absence of the legitimate Spanish monarch. It tried to accommodate the aspirations of American-born Spaniards (''criollos

In Hispanic America, criollo () is a term used originally to describe people of Spanish descent born in the colonies. In different Latin American countries the word has come to have different meanings, sometimes referring to the local-born majo ...

'') for more local control and equal standing with Peninsular-born Spaniards, known locally as peninsulares

In the context of the Spanish Empire, a ''peninsular'' (, pl. ''peninsulares'') was a Spaniard born in Spain residing in the New World, Spanish East Indies, or Spanish Guinea. Nowadays, the word ''peninsulares'' makes reference to Peninsular ...

. This political process had far-reaching impacts in New Spain during the independence war and beyond. Pre-existing cultural, religious, and racial divides in Mexico played a major role in not only the development of the independence movement but also the development of the conflict as it progressed.

In September 1808, peninsular-born Spaniards in New Spain overthrew Viceroy José de Iturrigaray (1803–08), who had been appointed before the French invasion. In 1810, American-born Spaniards in favor of independence began plotting an uprising against Spanish rule. It occurred when the parish priest of the village of Dolores, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican W ...

, issued the Cry of Dolores

The Cry of Dolores ( es, Grito de Dolores, links=no, region=MX) occurred in Dolores, Mexico, on 16 September 1810, when Roman Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla rang his church bell and gave the call to arms that triggered the Mexican W ...

on 16 September 1810. The Hidalgo revolt began the armed insurgency for independence, lasting until 1821. The colonial regime did not expect the size and duration of the insurgency, which spread from the Bajío

El Bajío (the ''lowland'') is a cultural and geographical region within the central Mexican plateau which roughly spans from north-west of the Mexico City metropolitan area to the main silver mines in the northern-central part of the country. Thi ...

region north of Mexico City to the Pacific and Gulf Coasts. After Napoleon's defeat, Ferdinand VII succeeded to the throne of the Spanish Empire in 1814 and promptly repudiated the constitution, and returned to absolutist rule. When Spanish liberals overthrew the autocratic rule of Ferdinand VII in 1820, conservatives in New Spain saw political independence as a way to maintain their position. Former royalists and old insurgents allied under the Plan of Iguala

The Plan of Iguala, also known as The Plan of the Three Guarantees ("Plan Trigarante") or Act of Independence of North America, was a revolutionary proclamation promulgated on 24 February 1821, in the final stage of the Mexican War of Independenc ...

and forged the Army of the Three Guarantees

At the end of the Mexican War of Independence, the Army of the Three Guarantees ( es, Ejército Trigarante or ) was the name given to the army after the unification of the Spanish troops led by Agustín de Iturbide and the Mexican insurgent troo ...

. The momentum of independence saw the collapse of the royal government in Mexico and the Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guara ...

ended the conflict.

The mainland of New Spain was organized as the First Mexican Empire

The Mexican Empire ( es, Imperio Mexicano, ) was a constitutional monarchy, the first independent government of Mexico and the only former colony of the Spanish Empire to establish a monarchy after independence. It is one of the few modern-era ...

, led by Agustín de Iturbide

Agustín de Iturbide (; 27 September 178319 July 1824), full name Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu and also known as Agustín of Mexico, was a Mexican army general and politician. During the Mexican War of Independence, he built ...

.''Mexico independiente, 1821–1851'', Monografias, 1996; accessed 21 December 2018. This ephemeral Catholic monarchy was overthrown and a

federal republic

A federal republic is a federation of states with a republican form of government. At its core, the literal meaning of the word republic when used to reference a form of government means: "a country that is governed by elected representatives ...

was declared in 1823 and codified in the Constitution of 1824

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1824 ( es, Constitución Federal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos de 1824) was enacted on October 4 of 1824, after the overthrow of the Mexican Empire of Agustin de Iturbide. In the new Fr ...

. After some Spanish reconquest attempts, including the expedition of Isidro Barradas in 1829, Spain under the rule of Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successi ...

recognized the independence of Mexico in 1836.

Prior challenges to crown rule

There is evidence that from an early period in post-conquest Mexican history that some began articulating the idea of a separate Mexican identity, though this was reserved to elite Creole circles. Despite that, challenges to Spanish imperial power before the insurgency for independence were rare, though some are of note. One early challenge was by Spanish conquerors whoseencomienda

The ''encomienda'' () was a Spanish labour system that rewarded conquerors with the labour of conquered non-Christian peoples. The labourers, in theory, were provided with benefits by the conquerors for whom they laboured, including military ...

grants from the crown, rewards for conquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, ...

were to be ended following the deaths of the current grant holders. The encomenderos' conspiracy included Don Martín Cortés (son of Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

). Martín Cortés was exiled, and other conspirators were executed. Another challenge occurred in 1624, when elites ousted the reformist viceroy who sought to break up rackets from which they profited and curtail opulent displays of clerical power. Viceroy Marqués de Gelves was removed, following an urban riot of Mexico City commoners in 1624 stirred up by those elites. The crowd was reported to have shouted, "Long live the King! Love live Christ! Death to bad government! Death to the heretic Lutheran iceroy Gelves Arrest the viceroy!" The attack was against Gelves, seen as a bad representative of the crown and not against the monarchy or colonial rule itself. In 1642, there was also a brief conspiracy in the mid-seventeenth century to unite American-born Spaniards, blacks, Indians and casta

() is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas it also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical f ...

s against the Spanish crown and proclaim Mexican independence. The man seeking to bring about independendence called himself Don Guillén Lampart y Guzmán, an Irishman born William Lamport

William Lamport (or Lampart) (1611/1615 – 1659) was an Irish Catholic adventurer, known in Mexico as "Don Guillén de Lamport (or Lombardo) y Guzmán". He was tried by the Mexican Inquisition for sedition and executed in 1659. He claimed to b ...

. Lamport's conspiracy was discovered, and he was arrested by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

in 1642, and executed fifteen years later for sedition

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, esta ...

. There is a statue of Lamport in the mausoleum at the base of the Angel of Independence

The Angel of Independence, most commonly known by the shortened name ''El Ángel'' and officially known as ''Monumento a la Independencia'' ("Monument to Independence"), is a victory column on a roundabout on the major thoroughfare of Paseo de ...

in Mexico City.

At the end of the seventeenth century, there was a major riot in Mexico City, where a plebeian mob attempted to burn down the viceroy's palace and the archbishop's residence. A painting by Cristóbal de Villalpando

Cristóbal de Villalpando (ca. 1649 – 20 August 1714) was a Baroque Criollo artist from New Spain, arts administrator and captain of the guard. He painted prolifically and produced many Baroque works now displayed in several Mexican cathedrals ...

shows the damage of the 1692 ''tumulto''. Unlike the earlier riot in 1624 in which elites were involved and the viceroy ousted, with no repercussions against the instigators, the 1692 riot was by plebeians alone and racially motivated. The rioters attacked key symbols of Spanish power and shouted political slogans. "Kill the merican-bornSpaniards and the ''Gachupines'' berian-born Spaniardswho eat our corn! We go to war happily! God wants us to finish off the Spaniards! We do not care if we die without confession! Is this not our land?" The viceroy attempted to address the cause of the riot, a hike in maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

prices that affected the urban poor. But the 1692 riot "represented class warfare that put Spanish authority at risk. Punishment was swift and brutal, and no further riots in the capital challenged the Pax Hispanica."

Food shortages, due to a growing population and severe droughts led to two food riots, one in 1785 and one in 1808. The first riot was more severe than the second and both culminated in violence and anger at officials of the colonial regime. However, there is no direct link between these riots and the independence movement, although the 1808–1809 food shortage may have been a contributory factor for popular resentment at the current political regime.

The various indigenous rebellions in the colonial era were often to throw off crown rule, but local rebellions to redress perceived wrongs not deal with by authorities. They were not a broad independence movement as such. However, during the war of independence, issues at the local level in rural areas constituted what some historians has called "the other rebellion." Van Young, Eric ''The Other Rebellion: Popular Violence, Ideology, and the Mexican Struggle for Independence, 1810–1821''. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

Before the events of 1808 upended the political situation in New Spain, there was an isolated and abortive 1799 Conspiracy of the Machetes

The Conspiracy of the Machetes ( es, La Conspiración de los Machetes) was an unsuccessful rebellion against the Spanish in New Spain in 1799. Although the conspiracy posed no threat to Spanish rule, nevertheless it was a shock to the rulers. Com ...

by a small group in Mexico City seeking independence.

Age of Revolution, Spain and New Spain

The eighteenth and early nineteenth-centuryAge of Revolution

The Age of Revolution is a period from the late-18th to the mid-19th centuries during which a number of significant revolutionary movements occurred in most of Europe and the Americas. The period is noted for the change from absolutist monarc ...

was already underway when the 1808 Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula destabilized not only Spain but also Spain's overseas possessions. In 1776, the Anglo-American Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centu ...

and the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

successfully gained their independence in 1783, with the help of both the Spanish Empire and Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

's French monarchy. Louis XVI was toppled in the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

of 1789, with the aristocrats and the king himself losing his head in revolutionary violence. The rise of military strongman Napoleon Bonaparte brought some order within France, but the turmoil there set the stage for the black slave revolt in the French sugar colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

(Haiti) in 1791. The Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on ...

obliterated the slavocracy

A slavocracy, also known as a plantocracy, is a ruling class, political order or government composed of (or dominated by) slave owners and plantation owners.

A number of early European colonies in the New World were largely plantocracies, usually ...

and gained independence for Haiti in 1804.

Political and economic instability

Tensions in New Spain were growing after the mid-eighteenth-centuryBourbon reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of the new Crown's ...

. With the reforms the crown sought to increase the power of the Spanish state, decrease the power of the Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

, rationalize and tighten control over the royal bureaucracy by placing peninsular-born officials rather than American-born, and increase revenues to the crown by a series of measures that undermined the economic position of American-born elites. The reforms were an attempt to revive the political and economic fortunes of the Spanish empire, but many historians see the reforms as accelerating the breakdown of its unity. This involved often removing large quantities of wealth that had been obtained in Mexico, before exporting to other parts of the empire to fund the many wars the Spanish were fighting. The crown removed privileges (''fuero

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

eclesiástico'') from ecclesiastics that had a disproportionate impact on American-born priests, who filled the ranks of the lower clergy in New Spain. A number of parish priests, most famously Miguel Hidalgo

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican Wa ...

and José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

, subsequently became involved in the insurgency for independence. When the crown expelled the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

from Spain and the overseas empire in 1767, it had a major impact on elites in New Spain, whose Jesuit sons were sent into exile, and cultural institutions, especially universities and colleges where they taught were affected. In New Spain there were riots in protest of their expulsion.

Colonial rule was not based on outright coercion, until the early nineteenth century, since the crown did not have sufficient personnel and firepower to enforce its rule. Rather, the crown's hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

and legitimacy to rule was accepted and ruled through institutions acting as mediators between competing groups, many organized as corporate entities. These were ecclesiastics, mining entrepreneurs, elite merchants, as well as indigenous communities. The crown's creation of a standing military in the 1780s began to shift the political calculus since the crown could now use an armed force to impose rule. To aid building a standing military, the crown created set of corporate privileges (''fuero

(), (), () or () is a Spanish legal term and concept. The word comes from Latin , an open space used as a market, tribunal and meeting place. The same Latin root is the origin of the French terms and , and the Portuguese terms and ; all ...

'') for the military. For the first time, mixed-race castas and blacks had access to corporate privileges, usually reserved for white elites. Silver entrepreneurs and large-scale merchants also had access to special privileges. Lucrative overseas trade was in the hands of family firms based in Spain with ties to New Spain. Silver mining was the motor of the economy of New Spain, but also fueled the economies of Spain and the entire Atlantic world. That industry was in the hands of peninsula-born mine owners and their elite merchant investors. The crown imposed new regulations to boost their revenues from their overseas territories, particularly the consolidation of loans held by the Catholic Church. The 1804 Act of Consolidation called for borrowers to immediately repay the entire principal of the loan rather than stretch payments over decades. Borrowers were criollo land owners who could in no way repay large loans on short notice. The impact threatened the financial stability of elite Americans. The crown's forced extraction of funds is considered by some a key factor in Creoles considering political independence.

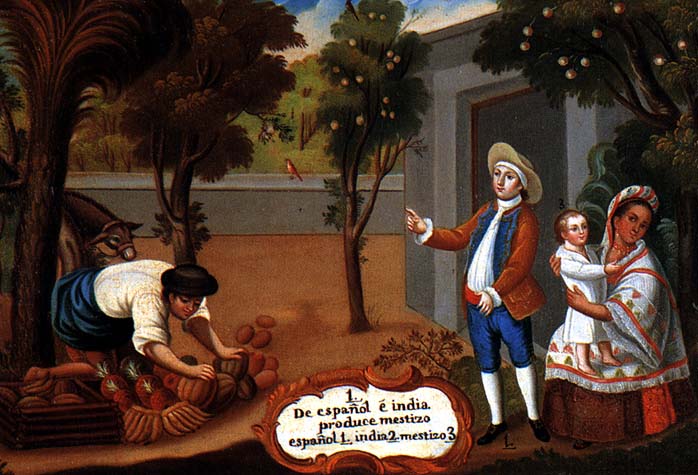

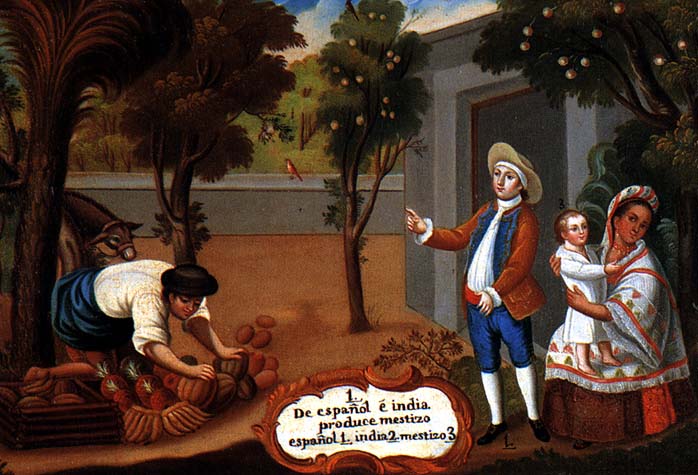

Religious, racial, and cultural tensions

Within the Spanish Empire there was an unofficial yet apparent racial hierarchy which affected the social mobility of those not at the top of society. White, Spanish-born Peninsulares were at the top where many occupied the highest levels of government. This was followed by Mexican-born pure Spanish descendents, who also occupied most government positions, and Creoles. Below this were indigenous groups, African-Mexicans and mixed race Mexicans. Many Creole elites deeply resented the lack of social mobility this brought as only Peninsular-born Spaniards could occupy the highest levels of government. This contributed to their reasoning behind backing the move for independence, to achieve power. They did not wish to overthrow the status quo entirely, as this would threaten their lucrative position in Mexican society. Instead, they wished to move up the social ladder, unable to under the unspoken racial hierarchy of the regime. Religious tension is arguably one of the biggest contributions to tension before the French invasion of Spain in 1808. Many Creoles, Mexican Spaniards and the majority of indigenous, mixed and African groups in Mexico practisedMexican Catholicism

, native_name_lang =

, image = Catedral_de_México.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt =

, caption = The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral.

, abbreviation =

, type = ...

while the ruling Peninsulares preferred Modern Catholicism. Mexican or traditional catholicism often worshipped through the use of relics, symbols and artifacts where they believe the Holy Spirit existed in the physical form of the artefact, and was a mix of traditional indigenous forms of worship and Catholicism. This contrasted with the view of modern Catholicism that many Peninsulares shared, where God was worshipped through divine artifacts and relics, but there was no religious presence within the physical artifact. Laws prohibiting Lay preachers, a major part of Mexican Catholicism, from preaching and restrictions on villagers to engage in processions around communal land to protect from unwanted spirits caused much outcry and prompted a multitude of legal battles between indigenous groups and the colonial regime through the separate indigenous courts. Not only this, but new laws essentially forcing indigenous groups to learn Spanish in schools and the taxation of Cofradias or Confraternities

A confraternity ( es, cofradía; pt, confraria) is generally a Christian voluntary association of laypeople created for the purpose of promoting special works of Christian charity or piety, and approved by the Church hierarchy. They are most ...

negatively affected the literacy and living standards in villages.

The ruling white Spanish elite and the majority of the country had very different views not only in culture and religion but on the role of government and social relations, with many elites viewing the government as a tool for progressing their own power, while indigenous groups saw the government as a communal vessel.

Leading up to the crisis in 1808 both Creole and Mexican-born Spaniards, and indigenous and mixed groups had come to dislike the colonial regime for different reasons.

French invasion of Spain and political crisis in New Spain, 1808–09

The Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula destabilized not only Spain but also Spain's overseas possessions. The viceroy was the "king’s living image" in New Spain. In 1808 viceroy José de Iturrigaray (1803–1808) was in office when Napoleon's forces invaded Iberia and deposed the Spanish monarch Charles IV and Napoleon's brotherJoseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the m ...

was declared the monarch. This turn of events set off a crisis of legitimacy. Viceroy Iturrigaray had been appointed by Charles IV, so his legitimacy to rule was not in doubt. In Mexico City, the city council (''ayuntamiento''), a stronghold of American-born Spaniards, began promoting ideas of autonomy for New Spain, and declaring New Spain to be on an equal basis to Spain. Their proposal would have created a legitimate, representative, and autonomous government in New Spain, but not necessarily breaking from the Spanish Empire. Opposition to that proposal came from conservative elements, including the peninsular-born judges of the High Court (''Audiencia''), who voiced peninsulars’ interests. Iturrigaray attempted to find a compromise between the two factions, but failed. Upon hearing the news of the Napoleonic invasion some elites suspected that Iturrigaray intended to declare the viceroyalty a sovereign state and perhaps establish himself as head of a new state. With the support of the archbishop, Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont, landowner Gabriel de Yermo

Gabriel J. de Yermo (1757 Sodupe, near Bilbao, Spain – 1813, Mexico City) was a wealthy landowner in New Spain, leader of the anti-independence party, and leader of the coup that overthrew Viceroy José de Iturrigaray in 1808.

Life before t ...

, the merchant guild of Mexico City ('' consulado''), and other members of elite society in the capital, Yermo led a coup d'état against the viceroy. They stormed the Viceregal Palace in Mexico City, the night of 15 September 1808, deposing the viceroy, and imprisoning him along with some American-born Spanish members of the city council. The peninsular rebels installed Pedro de Garibay

Pedro de Garibay (1729, Alcalá de Henares, Spain – July 7, 1815, Mexico City) was a Spanish military officer and, from September 16, 1808 to July 19, 1809, viceroy of New Spain.

Military career

Born in Alcalá de Henares in 1729 (some sour ...

as viceroy. Since he was not a crown appointee, but rather the leader of a rebel faction, creoles viewed him as an illegitimate representative of the crown. The event radicalized both sides. For creoles, it was clear that to gain power they needed to form conspiracies against peninsular rule, and later they took up arms to achieve their goals. Garibay was of advanced years and held office for just a year, replaced by Archbishop Lizana y Beaumont, also holding office for about a year. There was a precedent for the archbishop serving as viceroy, and given that Garibay came to power by coup, the archbishop had more legitimacy as ruler. Francisco Javier Venegas

Francisco Javier Venegas de Saavedra y Ramínez de Arenzana, 1st Marquess of Reunión and New Spain, KOC (1754 in Zafra, Badajoz, Spain – 1838 in Zafra, Spain) was a Spanish general in the Spanish War of Independence and later viceroy of ...

was appointed viceroy and landed in Veracruz in August, reaching Mexico City 14 September 1810. The next day, Hidalgo issued his call to arms in Dolores. Immediately after the Mexico City coup ousting Iturrigaray, juntas in Spain created the Supreme Central Junta of Spain and the Indies, on 25 September 1808 in Aranjuez. Its creation was a major step in the political development in the Spanish empire, once it became clear that there needed to be a central governing body rather than scattered juntas of particular regions. Joseph I of Spain had invited representatives from Spanish America to

Immediately after the Mexico City coup ousting Iturrigaray, juntas in Spain created the Supreme Central Junta of Spain and the Indies, on 25 September 1808 in Aranjuez. Its creation was a major step in the political development in the Spanish empire, once it became clear that there needed to be a central governing body rather than scattered juntas of particular regions. Joseph I of Spain had invited representatives from Spanish America to Bayonne

Bayonne (; eu, Baiona ; oc, label= Gascon, Baiona ; es, Bayona) is a city in Southwestern France near the Spanish border. It is a commune and one of two subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine r ...

, France for a constitutional convention to discuss their status in the new political order. It was a shrewd political move, but none accepted the invitation. However, it became clear to the Supreme Central Junta that keeping his overseas kingdoms loyal was imperative. Silver from New Spain was vital for funding the war against France. The body expanded to include membership from Spanish America, with the explicit recognition that they were kingdoms in their own right and not colonies of Spain. Elections were set to send delegates to Spain to participate in the Supreme Central Junta. Although in the Spanish Empire there was not an ongoing tradition of high level representative government, found in Britain and British North America, towns in Spain and New Spain had elected representative ruling bodies, the ''cabildos Cabildo can refer to:

* Cabildo (council), a former Spanish municipal administrative unit governed by a council

* Cabildo abierto, or open cabildo, a Latin American political action for convening citizens to make important decisions

* Cabildo (Cuba ...

'' or ''ayuntamiento

''Ayuntamiento'' ()In other languages of Spain:

* ca, ajuntament ().

* gl, concello ().

* eu, udaletxea (). is the general term for the town council, or ''cabildo'', of a municipality or, sometimes, as is often the case in Spain and Latin Amer ...

s'', which came to play an important political role when the legitimate Spanish monarch was ousted in 1808. The successful 1809 elections in Mexico City for delegates to be sent to Spain had some precedents.

The Hidalgo revolt (1810–1811)

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (), was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican W ...

is now considered the father of Mexican independence. His uprising on 16 September 1810 is considered the spark igniting the Mexican War of Independence. He inspired tens of thousands of ordinary men to follow him, but did not organize them into a disciplined fighting force or have a broad military strategy, but he did want to destroy the old order. Fellow insurgent leader and second in command, Ignacio Allende

Ignacio José de Allende y Unzaga (, , ; January 21, 1769 – June 26, 1811), commonly known as Ignacio Allende, was a captain of the Spanish Army in New Spain who came to sympathize with the Mexican independence movement. He attended the secr ...

, said of Hidalgo, "Neither were his men amenable to discipline, nor was Hidalgo interested in regulations." Hidalgo issued a few important decrees in the later stage of the insurgency, but did not articulate a coherent set of goals much beyond his initial call to arms denouncing bad government. Only following Hidalgo's death in 1811 under the leadership of his former seminary student, Father José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

, was a document created that made explicit the goals of the insurgency, the ''Sentimientos de la Nación

''Sentimientos de la Nación'' ("Feelings of the Nation"; occasionally rendered as "Sentiments of the Nation") was a document presented by José María Morelos y Pavón, leader of the insurgents in the Mexican War of Independence, to the National ...

'' ("Sentiments of the Nation") (1813). One clear point was political independence from Spain. Despite its having only a vague ideology, Hidalgo's movement demonstrated the massive discontent and power of Mexico's plebeians as an existential threat to the imperial regime. The government focused its resources on defeating Hidalgo's insurgents militarily and in tracking down and publicly executing its leadership. But by then the insurgency had spread beyond its original region and leadership.

Hidalgo was a learned priest who knew multiple languages, had a significant library, and was friends men who held Enlightenment views. He held the important position of rector of the Seminary of San Nicolás, but had run afoul of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

for unorthodox beliefs and speaking against the monarchy. He had already sired two daughters with Josefa Quintana. Following the death of his brother Joaquín in 1803, Hidalgo, who was having money problems due to debts on landed estates he owned, became curate of the poor parish of Dolores. He became member of a group of well-educated American-born Spaniards in Querétaro

Querétaro (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Querétaro ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Querétaro, links=no; Otomi: ''Hyodi Ndämxei''), is one of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. It is divided into 18 municipalities. Its cap ...

. They met under the guise of being a literary society, supported by the wife of crown official (''corregidor'') Miguel Domínguez, Josefa Ortíz de Domínguez, known now as "La Corregidora." Instead the members discussed the possibility of a popular rising, similar to one that already had recently been quashed in Valladolid (now Morelia

Morelia (; from 1545 to 1828 known as Valladolid) is a city and municipal seat of the municipality of Morelia in the north-central part of the state of Michoacán in central Mexico. The city is in the Guayangareo Valley and is the capital and lar ...

) in 1809 in the name of Ferdinand VII.Guedea, Virginia, "Hidalgo Revolt" in ''Encyclopedia of Mexico''. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 638. Hidalgo was friends with Ignacio Allende

Ignacio José de Allende y Unzaga (, , ; January 21, 1769 – June 26, 1811), commonly known as Ignacio Allende, was a captain of the Spanish Army in New Spain who came to sympathize with the Mexican independence movement. He attended the secr ...

, a captain in the regiment of Dragoons in New Spain, who was also among the conspirators. The "Conspiracy of Querétaro" began forming cells in other Spanish cities in the north, including Celaya

Celaya (; ) is a city and its surrounding municipality in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico, located in the southeast quadrant of the state. It is the third most populous city in the state, with a 2005 census population of 310,413. The municipality f ...

, Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, San Miguel el Grande

San Miguel El Grande is a town and municipality in Oaxaca in south-western Mexico. The municipality covers an area of 4705 km².

It is part of the Tlaxiaco District in the south of the Mixteca Region

The Mixteca Region is a region in the s ...

, now named after Allende. Allende had served in a royal regiment during the rule of José de Iturrigaray, who was overthrown in 1808 by peninsular Spaniards who considered him too sympathetic to the grievances of American-born Spaniards. With the ouster of the viceroy, Allende turned against the new regime and was open to the conspiracy for independence. Hidalgo joined the conspiracy, and with Allende vouching for him rose to being one of its leaders. Word of the conspiracy got to crown officials, and the corregidor Domínguez cracked down, but his wife Josefa was able to warn Allende who then alerted Hidalgo. At this point there was no firm ideology or action plan, but the tip-off galvanized Hidalgo to action. On Sunday, 16 September 1810 with his parishioners gathered for mass, Hidalgo issued his call to arms, the ''Grito de Dolores

A ''grito'' or ''grito mexicano'' (, Spanish for "shout") is a common Mexican interjection, used as an expression.

Characteristics

This interjection is similar to the ''yahoo'' or '' yeehaw'' of the American cowboy during a hoedown, with added ...

''. It is unclear what Hidalgo actually said, since there are different accounts. The one which became part of the official record of accusation against Hidalgo was "Long live religion! Long live Our Most Holy Mother of Guadalupe! Long live Fernando VII! Long live America and down with bad government!"

From a small gathering at the Dolores church, other joined the rising including workers on local landed estates, prisoners liberated from jail, and a few members of a royal army regiment. Many estate workers' weapons were agricultural tools now to be used against the regime. Some were mounted and acted as a cavalry under the direction of their estate foremen. Others were poorly armed Indians with bows and arrows. The numbers joining the revolt rapidly swelled under Hidalgo's leadership, they began moving beyond the village of Dolores. Despite rising tensions following the events of 1808, the royal regime was largely unprepared for the suddenness, size, and violence of the movement.

From a small gathering at the Dolores church, other joined the rising including workers on local landed estates, prisoners liberated from jail, and a few members of a royal army regiment. Many estate workers' weapons were agricultural tools now to be used against the regime. Some were mounted and acted as a cavalry under the direction of their estate foremen. Others were poorly armed Indians with bows and arrows. The numbers joining the revolt rapidly swelled under Hidalgo's leadership, they began moving beyond the village of Dolores. Despite rising tensions following the events of 1808, the royal regime was largely unprepared for the suddenness, size, and violence of the movement.

Virgin of Guadalupe

Our Lady of Guadalupe ( es, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe ( es, Virgen de Guadalupe), is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus associated with a series of five Marian apparitions, which are believed t ...

, seized by Hidalgo from the church at Atotonilco, was symbolically important. The "dark virgin" was seen as a protector of dark-skinned Mexicans, and now seen as well as a liberator. Many men in Hidalgo's forces put the image of Guadalupe on their hats. Supporters of the imperial regime took as their patron the Virgin of Remedios, so that religious symbolism was used by both insurgents and royalists. There were a number of parish priests and other lower clergy in the insurgency, most prominently Hidalgo and José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

, but the Church hierarchy was flatly opposed. Insurgents were excommunicated by the clergy and clerics preached sermons against the insurgency.Guedea, Virginia. "The Old Colonialism Ends, the New Colonialism Begins" in ''The Oxford History of Mexico''. New York: Oxford University Press 2000, p. 289.

They were not organized in any formal fashion, more of a mass movement than an army. Hidalgo inspired his followers, but did not organize or train them as a fighting force, nor impose order and discipline on them. A few militia men in uniform joined Hidalgo's movement and attempted to create some military order and discipline, but they were few in number. The bulk of the royal army remained loyal to the imperial regime, but Hidalgo's rising had caught them unprepared and their response was delayed. Hidalgo's early victories gave the movement momentum, but "the lack of weapons, trained soldiers, and good officers meant that except in unusual circumstances the rebels could not field armies capable of fighting conventional battles against the royalists."

The growing insurgent force marched through towns including San Miguel el Grande and Celaya, where they met little resistance, and gained more followers. When they reached the town of Guanajuato on 28 September

Events Pre-1600

*48 BC – Pompey disembarks at Pelusium upon arriving in Egypt, whereupon he is assassinated by order of King Ptolemy XIII.

* 235 – Pope Pontian resigns. He is exiled to the mines of Sardinia, along with Hippolytus ...

, they found Spanish forces barricaded inside the public granary, Alhóndiga de Granaditas

The Alhóndiga de Granaditas (Regional Museum of Guanajuato) ( public grain exchange) is an old grain storage building in Guanajuato City, Mexico. This historic building was created to replace an old grain exchange near the city's river. The name ...

. Among them were some 'forced' Royalists, creoles who had served and sided with the Spanish. By this time, the rebels numbered 30,000 and the battle was horrific. They killed more than 500 European and American Spaniards, and marched on toward Mexico City.

The new viceroy quickly organized a defense, sending out the Spanish general Torcuato Trujillo with 1,000 men, 400 horsemen, and two cannons – all that could be found on such short notice. The crown had established a standing military in the late eighteenth century, granting non-Spaniards who served the ''fuero militar'', the only special privileges for mixed-race men were eligible. Indians were excluded from the military. Royal army troops of the professional army were supplemented by local militias. The regime was determined to crush the uprising and attempted to stifle malcontents who might be drawn to the insurgency.

The new viceroy quickly organized a defense, sending out the Spanish general Torcuato Trujillo with 1,000 men, 400 horsemen, and two cannons – all that could be found on such short notice. The crown had established a standing military in the late eighteenth century, granting non-Spaniards who served the ''fuero militar'', the only special privileges for mixed-race men were eligible. Indians were excluded from the military. Royal army troops of the professional army were supplemented by local militias. The regime was determined to crush the uprising and attempted to stifle malcontents who might be drawn to the insurgency.

Ignacio López Rayón

Ignacio López Rayón (July 31, 1773 in Tlalpujahua, Intendancy of Valladolid (present-day Michoacán), New Spain – February 2, 1832 in Mexico City) was a general who led the insurgent forces of his country after Miguel Hidalgo's death, ...

joined Hidalgo's forces whilst passing near Maravatío

Maravatío is a municipality in the Mexican state of Michoacán, representing 1.17% of its land area, or 691.55 km2.

Etymology

The modern word Maravatío comes from the Purépecha word Marhabatio, meaning a precious place or thing.

Hist ...

, Michoacan while en route to Mexico City and on 30 October, Hidalgo's army encountered Spanish military resistance at the Battle of Monte de las Cruces

The Battle of Monte de las Cruces was one of the pivotal battles of the early Mexican War of Independence, in October 1810.

It was fought between the insurgent troops of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and Ignacio Allende against the New Spain royalist ...

. As the Hidalgo and his forces surrounded Mexico City, a group of 2,5000 royalists women joined together under Ana Iraeta de Mier, to create and distribute pamphlets based on their loyalty towards Spain and help fellow loyalist families. Hidalgo's forces continued to fight and achieved victory. When the cannons were captured by the rebels, the surviving Royalists retreated to the city.

Despite apparently having the advantage, Hidalgo retreated, against the counsel of Allende. This retreat, on the verge of apparent victory, has puzzled historians and biographers ever since. They generally believe that Hidalgo wanted to spare the numerous Mexican citizens in Mexico City from the inevitable sacking and plunder that would have ensued. His retreat is considered Hidalgo's greatest tactical error and his failure to act "was the beginning of his downfall." Hidalgo moved west and set up headquarters in

Despite apparently having the advantage, Hidalgo retreated, against the counsel of Allende. This retreat, on the verge of apparent victory, has puzzled historians and biographers ever since. They generally believe that Hidalgo wanted to spare the numerous Mexican citizens in Mexico City from the inevitable sacking and plunder that would have ensued. His retreat is considered Hidalgo's greatest tactical error and his failure to act "was the beginning of his downfall." Hidalgo moved west and set up headquarters in Guadalajara

Guadalajara ( , ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th largest city by population in Mexico, while the Guadalaj ...

, where one of the worst incidents of violence against Spanish civilians occurred, a month of massacres from 12 December 1810 (the Feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe) to 13 January 1811. At his trial followoing his capture later that year, Hidalgo admitted to ordering the murders. None "were given a trial, nor was there any reason to do so, since he knew perfectly well they were innocent." In Guadalajara, the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe suddenly disappeared from insurgents' hats and there were many desertions.

The royalist forces, led by Félix María Calleja del Rey

Félix María Calleja del Rey y de la Gándara ( es, Félix María Calleja del Rey, primer conde de Calderón) (November 1, 1753, Medina del Campo, Spain – July 24, 1828, Valencia, Spain) was a Spanish military officer and viceroy of N ...

, were becoming more effective against disorganized and poorly armed of Hidalgo, defeating them at a bridge on the Calderón River The Calderón River is a tributary of the Lerma Santiago River that flows westward from the Altos region of Jalisco to its junction with the Lerma Santiago River in Tonalá.

The River contains a number of dams, including the Elías González Ch� ...

, forcing the rebels to flee north towards the United States, perhaps hoping they would attain financial and military support. They were intercepted by Ignacio Elizondo

Francisco Ignacio Elizondo Villarreal, (born Salinas Valley, New Kingdom of León, New Spain, March 9, 1766 - died San Marcos, Texas, New Spain, c. September 12, 1813), was a royalist military officer during the Mexican war of independence ag ...

, who pretended to join the fleeing insurgent forces. Hidalgo and his remaining soldiers were captured in the state of Coahuila

Coahuila (), formally Coahuila de Zaragoza (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Coahuila de Zaragoza ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Coahuila de Zaragoza), is one of the 32 states of Mexico.

Coahuila borders the Mexican states of N ...

at the Wells of Baján

Wells of Baján ( es, Norias de Baján) are water wells located between Saltillo and Monclova in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila. The small community near the wells is called Acatita de Baján. In the first phase of the Mexican War of In ...

(''Norias de Baján''). When the insurgents adopted the tactics of guerrilla warfare and operated where it was effective, such as in the hot country of southern Mexico, they were able to undermine the royalist army. Around Guanajuato

Guanajuato (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Guanajuato), is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city i ...

, regional insurgent leader for a time successfully combined insurgency with banditry. With the capture of Hidalgo and the creole leadership in the north, this phase of the insurgency was at an end.

The captured rebel leaders were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death, except for Mariano Abasolo

Jose Mariano de Abasolo (1783–1816) was a Mexican revolutionist, born at Dolores, Guanajuato. He participated in the revolution started by Miguel Hidalgo.

Biography

In 1809 he belonged to one of the first conspiracy groups located in Val ...

, who was sent to Spain to serve a life sentence in prison. Allende, Jiménez, and Aldama were executed on 26 June 1811, shot in the back as a sign of dishonor. Hidalgo, as a priest, had to undergo a civil trial and review by the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

. He was eventually stripped of his priesthood, found guilty, and executed on 30 July 1811. The heads of Hidalgo, Allende, Aldama, and Jiménez were preserved and hung from the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas of Guanajuato as a grim warning to those who dared follow in their footsteps.

Insurgency in the South under Morelos, 1811–1815

Warfare in the northern Bajío region waned after the capture and execution of the insurgency's creole leadership, but the insurgency had already spread to other more southern regions, to the towns of Zitácuaro, Cuautla, Antequera (now Oaxaca) towns where a new leadership had emerged. Priests

Warfare in the northern Bajío region waned after the capture and execution of the insurgency's creole leadership, but the insurgency had already spread to other more southern regions, to the towns of Zitácuaro, Cuautla, Antequera (now Oaxaca) towns where a new leadership had emerged. Priests José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

and Mariano Matamoros

Mariano Matamoros y Guridi (August 14, 1770 – February 3, 1814) was a Mexican Roman Catholic priest and revolutionary rebel soldier of the Mexican War of Independence, who fought for independence against Spain in the early 19th century.

B ...

, as well as Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

, Guadalupe Victoria

Guadalupe Victoria (; 29 September 178621 March 1843), born José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, was a Mexican general and political leader who fought for independence against the Spanish Empire in the Mexican War of Independence. ...

, and Ignacio López Rayón

Ignacio López Rayón (July 31, 1773 in Tlalpujahua, Intendancy of Valladolid (present-day Michoacán), New Spain – February 2, 1832 in Mexico City) was a general who led the insurgent forces of his country after Miguel Hidalgo's death, ...

carried on the insurgency on a different basis, organizing their forces, using guerrilla tactics, and importantly for the insurgency, creating organizations and creating written documents that articulated the insurgents' goals.

Following the execution of Hidalgo and other insurgents, leadership of the remaining insurgent movement initially coalesced under Ignacio López Rayón

Ignacio López Rayón (July 31, 1773 in Tlalpujahua, Intendancy of Valladolid (present-day Michoacán), New Spain – February 2, 1832 in Mexico City) was a general who led the insurgent forces of his country after Miguel Hidalgo's death, ...

, a civilian lawyer and businessman. He had been stationed in Saltillo, Coahuila with 3,500 men and 22 cannons. When he heard of the capture of the insurgent leaders, he fled south on 26 March 1811 to continue the fight. He subsequently fought the Spanish in the battles of Puerto de Piñones, Zacatecas

, image_map = Zacatecas in Mexico (location map scheme).svg

, map_caption = State of Zacatecas within Mexico

, coordinates =

, coor_pinpoint =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type ...

, El Maguey, and Zitácuaro

Zitácuaro, officially known as Heroica Zitácuaro, is a city in the Mexican state of Michoacán. The city is the administrative centre for the surrounding municipality of the same name, which lies at the extreme eastern side of Michoacán and ...

.

In an important step, Rayón organized the '' Suprema Junta Gubernativa de América'' (Supreme National Governing Junta of America), which claimed legitimacy to lead the insurgency. Rayón articulated '' Elementos constitucionales'', which states that "Sovereignty arises directly from the people, resides in the person of Ferdinand VII, and is exercised by the ''Suprema Junta Gubernativa de América''. The Supreme Junta generated a flood of detailed regulations and orders. On the ground, Father José María Morelos

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón () (30 September 1765 – 22 December 1815) was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of ...

pursued successful military engagements, accepting the authority of the Supreme Junta. After winning victories and taking the port of Acapulco

Acapulco de Juárez (), commonly called Acapulco ( , also , nah, Acapolco), is a city and major seaport in the state of Guerrero on the Pacific Coast of Mexico, south of Mexico City. Acapulco is located on a deep, semicircular bay and has ...

, then the towns Tixtla, Izúcar, and Taxco, Morelos was besieged for 72 days by royalist troops under Calleja at Cuautla. The Junta failed to send aid to Morelos. Morelos's troops held out and broke out of the siege, going on to take Antequera, (now Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, Huāxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the Federative Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 570 municipaliti ...

). The relationship between Morelos and the Junta soured, with Morelos complaining, "Your disagreements have been of service to the enemy."

Morelos was a real contrast to Hidalgo, although both were rebel priests. Both had sympathy for Mexico's downtrodden, but Morelos was of mixed-race while Hidalgo was an American-born Spaniard, so Morelos experientially understood racial discrimination in the colonial order. On more practical grounds, Morelos built an organized and disciplined military force, while Hidalgo's followers lacked arms, training, or discipline, an effective force that the royal army took seriously. Potentially Morelos could have taken the colony's second largest city, Puebla de los Angeles, situated halfway between the port of Veracruz and the capital, Mexico City. To avert that strategic disaster, which would have left the capital cut off from its main port, viceroy Venegas transferred Calleja from the Bajío to deal with Morelos's forces. Morelos's forces moved south and took Oaxaca, allowing him to control most of the southern region. During this period, the insurgency had reason for optimism and formulated documents declaring independence and articulating a vision for a sovereign Mexico.

Morelos was not ambitious to become leader of the insurgency, but it was clear that he was recognized by insurgents as its supreme military commander. He moved swiftly and decisively, stripping Rayón of power, dissolving the Supreme Junta, and in 1813, Morelos convened the Congress of Chilpancingo

The Congress of Chilpancingo ( es, Congreso de Chilpancingo), also known as the Congress of Anáhuac, was the first, independent congress that replaced the Assembly of Zitácuaro, formally declaring itself independent from the Spanish crown. It w ...

, also known as the Congress of Anáhuac. The congress brought together representatives of the insurgency together. Morelos formulated his Sentiments of the Nation, addressed to the congress. In point 1, he clearly and flatly states that "America is free and independent of Spain." On 6 November of that year, the Congress signed the first official document of independence, known as the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America

The Solemn Act of Northern America's Declaration of Independence ( es, Acta Solemne de la Declaración de Independencia de la América Septentrional) is the first Mexican legal historical document which established the separation of Mexico from S ...

. In addition to declaring independence from Spain, the Morelos called for the establishment of Catholicism as the only religion (but with certain restrictions), the abolition of slavery and racial distinctions between and of all other nations," going on in point 5 to say, "sovereignty springs directly from the People." His second point makes the "Catholic Religion" the only one permissible, and that "Catholic dogma shall be sustained by the Church hierarchy" (point 4). The importance of Catholicism is further emphasized to mandate December 12, the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe, as a day to honor her. A provision of key importance to dark-skinned plebeians (point 15) is "That slavery is proscribed forever, , as well as the distinctions of caste ace so that all shall be equal; and that the only distinction between one American and another shall be that between vice and virtue.". Also important for Morelos's vision of the new nation was equality before the law (point 13), rather than maintaining special courts and privileges ( fueros) to particular groups, such as churchmen, miners, merchants, and the military.

The Congress elected Morelos as the head of the executive branch of government, as well as supreme commander of the insurgency, coordinating its far-flung components. The formal statement by the Congress of Chilpancingo, the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence, is an important formal document in Mexican history, since it declares Mexico an independent nation and lays out its powers as a sovereign state to make war and peace, to appoint ambassadors, and to have standing with the Papacy, rather than indirectly through the Spanish monarch. The document enshrines Roman Catholicism the sole religion.

Calleja Calleja is a surname found in Spain (as well as countries people of Hispanic descent) and Malta. It is unclear whether the Maltese and Spanish surnames are related or a coincidence, perhaps caused by romanization.

Variations

Variations in spelli ...

restructured the royal army in an attempt to crush the insurgency, creating commands in Puebla, Valladolid (now Morelia), Guanajuato, and Nueva Galicia, with experienced peninsular military officers to lead them. American-born officer Agustín de Iturbide

Agustín de Iturbide (; 27 September 178319 July 1824), full name Agustín Cosme Damián de Iturbide y Arámburu and also known as Agustín of Mexico, was a Mexican army general and politician. During the Mexican War of Independence, he built ...

was part of this royalist leadership. Brigadier Ciriaco de Llano captured and executed Mariano Matamoros

Mariano Matamoros y Guridi (August 14, 1770 – February 3, 1814) was a Mexican Roman Catholic priest and revolutionary rebel soldier of the Mexican War of Independence, who fought for independence against Spain in the early 19th century.

B ...

, an effective insurgent. After the dissolution of the Congress of Chilpancingo, Morelos was captured 5 November 1815, interrogated, was tried and executed by firing squad. With his death, conventional warfare ended and guerrilla warfare continued uninterrupted.

Insurgency under Vicente Guerrero, 1815–1820

With the execution of Morelos in 1815, Vicente Guerrero emerged as the most important leader of the insurgency. From 1815 to 1821 most of the fighting for independence from Spain was by guerrilla forces in the ''tierra caliente'' (hot country) of southern Mexico and to a certain extent in northern New Spain. In 1816,

With the execution of Morelos in 1815, Vicente Guerrero emerged as the most important leader of the insurgency. From 1815 to 1821 most of the fighting for independence from Spain was by guerrilla forces in the ''tierra caliente'' (hot country) of southern Mexico and to a certain extent in northern New Spain. In 1816, Francisco Javier Mina

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name ''Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed " Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comunitatis'' (father of ...

, a Spanish military leader who had fought against Ferdinand VII, joined the independence movement. Mina and 300 men landed at ''Rio Santander'' (Tamaulipas

Tamaulipas (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tamaulipas ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Tamaulipas), is a state in the northeast region of Mexico; one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Federal Entiti ...

) in April, in 1817 and fought for seven months until his capture by royalist forces in November 1817.

Two insurgent leaders arose: Guadalupe Victoria

Guadalupe Victoria (; 29 September 178621 March 1843), born José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix, was a Mexican general and political leader who fought for independence against the Spanish Empire in the Mexican War of Independence. ...

(born José Miguel Fernández y Félix) in Puebla

Puebla ( en, colony, settlement), officially Free and Sovereign State of Puebla ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Puebla), is one of the 32 states which comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 217 municipalities and its cap ...

and Vicente Guerrero

Vicente Ramón Guerrero (; baptized August 10, 1782 – February 14, 1831) was one of the leading revolutionary generals of the Mexican War of Independence. He fought against Spain for independence in the early 19th century, and later served as ...

in the village of Tixla, in what is now the state of Guerrero

Guerrero is one of the 32 states that comprise the 32 Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided in 81 municipalities and its capital city is Chilpancingo and its largest city is Acapulcocopied from article, GuerreroAs of 2020, Guerrero the pop ...

. Both gained allegiance and respect from their followers. Believing the situation under control, the Spanish viceroy issued a general pardon to every rebel who would lay down his arms. Many did lay down their arms and received pardons, but when the opportunity arose, they often returned to the insurgency. The royal army controlled the major cities and towns, but whole swaths of the countryside were not pacified. From 1816 to 1820, the insurgency was stalemated, but not stamped out. Royalist military officer, Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. usually known as Santa Ann ...

led amnestied former insurgents, pursuing insurgent leader Guadalupe Victoria. Insurgents attacked key roads, vital for commerce and imperial control, such that the crown sent a commander from Peru, Brigadier Fernando Miyares y Mancebo, to build a fortified road between the port of Veracruz and Jalapa, the first major stopping point on the way to Mexico City. The rebels faced stiff Spanish military resistance and the apathy of many of the most influential criollos.