Mellonomics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrew William Mellon (; March 24, 1855 – August 26, 1937), sometimes A. W. Mellon, was an American banker, businessman, industrialist, philanthropist, art collector, and politician. From the wealthy

In 1902, Mellon reorganized T. Mellon & Sons as the Mellon National Bank, a federally chartered National Bank. Andrew Mellon, Richard Mellon, and Frick drew up a new business arrangement in which the three of them jointly controlled the Union Trust Company, which in turn controlled Mellon National Bank. They also established Union Savings Bank, which accepted deposits by mail, and the Mellon banks flourished in the first years of the 20th century. While Mellon's financial empire prospered, his investments in other areas, including Pittsburgh's streetcar network, the Union Steel Company (which was bought out by U.S. Steel), and the Carborundum Company, also paid off handsomely. Another successful Mellon investment, the

In 1902, Mellon reorganized T. Mellon & Sons as the Mellon National Bank, a federally chartered National Bank. Andrew Mellon, Richard Mellon, and Frick drew up a new business arrangement in which the three of them jointly controlled the Union Trust Company, which in turn controlled Mellon National Bank. They also established Union Savings Bank, which accepted deposits by mail, and the Mellon banks flourished in the first years of the 20th century. While Mellon's financial empire prospered, his investments in other areas, including Pittsburgh's streetcar network, the Union Steel Company (which was bought out by U.S. Steel), and the Carborundum Company, also paid off handsomely. Another successful Mellon investment, the

Following Harding's victory in the 1920 presidential election, Harding considered various candidates for Secretary of the Treasury, including

Following Harding's victory in the 1920 presidential election, Harding considered various candidates for Secretary of the Treasury, including  As Treasury Secretary, Mellon focused on balancing the budget and paying off World War I debts in the midst of the

As Treasury Secretary, Mellon focused on balancing the budget and paying off World War I debts in the midst of the  Mellon instead advocated for the retention of a progressive income tax that would serve as an important, but not primary, source of revenue for the federal government. His so-called "scientific taxation" was designed to maximize federal revenue while minimizing the impact on business and industry. The central tenet of Mellon's tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive tax that affected only high-income earners. Mellon argued that such a reduction would minimize tax avoidance and would not affect federal revenue because it would lead to greater economic growth. He hoped that tax reform would encourage high earners to move their savings from tax-exempt state and municipal bonds to taxable, higher yield industrial stocks. Though much of the tax plan that he proposed had been developed by former Wilson administration officials Russell Cornell Leffingwell and Seymour Parker Gilbert, the press generally referred to it as the "Mellon Plan".Murnane (2004), pp. 820–822

The Revenue Act of 1918 had set a top marginal income tax rate of 73% and a corporate tax of approximately 10%. Due in part to the size of the U.S. public debt, which had grown from $1 billion before the war to $24 billion in 1921, the provisions of the Revenue Act of 1918 remained in place when Harding took office. In 1921, the Treasury Department and the

Mellon instead advocated for the retention of a progressive income tax that would serve as an important, but not primary, source of revenue for the federal government. His so-called "scientific taxation" was designed to maximize federal revenue while minimizing the impact on business and industry. The central tenet of Mellon's tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive tax that affected only high-income earners. Mellon argued that such a reduction would minimize tax avoidance and would not affect federal revenue because it would lead to greater economic growth. He hoped that tax reform would encourage high earners to move their savings from tax-exempt state and municipal bonds to taxable, higher yield industrial stocks. Though much of the tax plan that he proposed had been developed by former Wilson administration officials Russell Cornell Leffingwell and Seymour Parker Gilbert, the press generally referred to it as the "Mellon Plan".Murnane (2004), pp. 820–822

The Revenue Act of 1918 had set a top marginal income tax rate of 73% and a corporate tax of approximately 10%. Due in part to the size of the U.S. public debt, which had grown from $1 billion before the war to $24 billion in 1921, the provisions of the Revenue Act of 1918 remained in place when Harding took office. In 1921, the Treasury Department and the

As the economy recovered from recession and began to experience the prosperity of the

As the economy recovered from recession and began to experience the prosperity of the

Coolidge surprised many observers by announcing that he would not seek another term in August 1927. The decision left Hoover as the presumed front-runner for the

Coolidge surprised many observers by announcing that he would not seek another term in August 1927. The decision left Hoover as the presumed front-runner for the

Secretary Mellon had helped persuade the Federal Reserve Board to lower interest rates in 1921 and 1924; lower interest rates contributed to a booming economy, but they also encouraged stock market speculation. In 1928, responding to increasing fears of the dangers of speculation and a booming stock market, the Federal Reserve Board began raising interest rates. Mellon favored another interest rate increase in 1929, and in August 1929 the Federal Reserve Board raised the discount rate to six percent. The higher rate failed to curb speculation, and the activity on the stock market continued to grow. In October 1929, the

Secretary Mellon had helped persuade the Federal Reserve Board to lower interest rates in 1921 and 1924; lower interest rates contributed to a booming economy, but they also encouraged stock market speculation. In 1928, responding to increasing fears of the dangers of speculation and a booming stock market, the Federal Reserve Board began raising interest rates. Mellon favored another interest rate increase in 1929, and in August 1929 the Federal Reserve Board raised the discount rate to six percent. The higher rate failed to curb speculation, and the activity on the stock market continued to grow. In October 1929, the

Emulating his father, Mellon eschewed philanthropy for much of his life, but in the early 1900s, he began donating to local organizations such as the

Emulating his father, Mellon eschewed philanthropy for much of his life, but in the early 1900s, he began donating to local organizations such as the

The

The

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article on history of the Mellons and Mellon Financial

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mellon, Andrew W. 1855 births 1937 deaths 20th-century American politicians Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom American art collectors American bankers American Episcopalians American people of Scotch-Irish descent American philanthropists Coolidge administration cabinet members Great Depression in the United States Harding administration cabinet members Hoover administration cabinet members Mellon family National Gallery of Art Pennsylvania Republicans Politicians from Pittsburgh United States Secretaries of the Treasury University of Pittsburgh alumni Gilded Age Burials in Virginia Old Right (United States) Museum founders People acquitted of crimes 20th-century American diplomats

Mellon family

The Mellon family is a wealthy and influential American family from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The family includes Andrew Mellon, one of the longest-serving U.S. Treasury Secretaries, along with prominent members in the judicial, banking, financi ...

of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Pennsylvania, he established a vast business empire before moving into politics. He served as United States Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

from March 9, 1921 to February 12, 1932, presiding over the boom years of the 1920s and the Wall Street crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

. A conservative Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

, Mellon favored policies that reduced taxation and the national debt in the aftermath of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Mellon's father, Thomas Mellon

Thomas Mellon (February 3, 1813 – February 3, 1908) was an American entrepreneur, lawyer, and judge, best known as the founder of Mellon Bank and patriarch of the Mellon family of Pittsburgh.

Early life

Mellon was born to farmers Andrew Mell ...

, rose to prominence in Pittsburgh as a banker and attorney. Andrew began working at his father's bank, T. Mellon & Sons, in the early 1870s, eventually becoming the leading figure in the institution. He later renamed T. Mellon & Sons as Mellon National Bank and established another financial institution, the Union Trust Company. By the end of 1913, Mellon National Bank held more money in deposits than any other bank in Pittsburgh, and the second-largest bank in the region was controlled by Union Trust. In the course of his business career, Mellon owned or helped finance large companies including Alcoa, the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

, Old Overholt

Old Overholt is America's oldest continually maintained brand of whiskey, was founded in West Overton, Pennsylvania, in 1810. Old Overholt is a rye whiskey distilled by A. Overholt & Co., currently a subsidiary of Beam Suntory, which is a sub ...

whiskey, Standard Steel Car Company

The Standard Steel Car Company (SSC) was a manufacturer of railroad rolling stock in the United States that existed between 1902 and 1934.

Established in 1902 in Butler, Pennsylvania by John M. Hansen and "Diamond Jim" Brady, the company quic ...

, Westinghouse Electric Corporation

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was renamed "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in ...

, Koppers

Koppers is a global chemical and materials company based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States in an art-deco 1920s skyscraper, the Koppers Tower.

Structure

Koppers is an integrated global producer of carbon compounds, chemicals, and trea ...

, the Pittsburgh Coal Company

The Pittsburgh Terminal Coal Company was a bituminous coal mining company based in Pittsburgh and controlled by the Mellon family. It operated mines in the Pittsburgh Coalfield, including mines in Becks Run and Horning, Pennsylvania. Unusuall ...

, the Carborundum Company, Union Steel Company, the McClintic-Marshall Construction Company, Gulf Oil

Gulf Oil was a major global oil company in operation from 1901 to 1985. The eighth-largest American manufacturing company in 1941 and the ninth-largest in 1979, Gulf Oil was one of the so-called Seven Sisters oil companies. Prior to its merger ...

, and numerous others. He was also an influential donor to the Republican Party during the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Wes ...

and the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

.

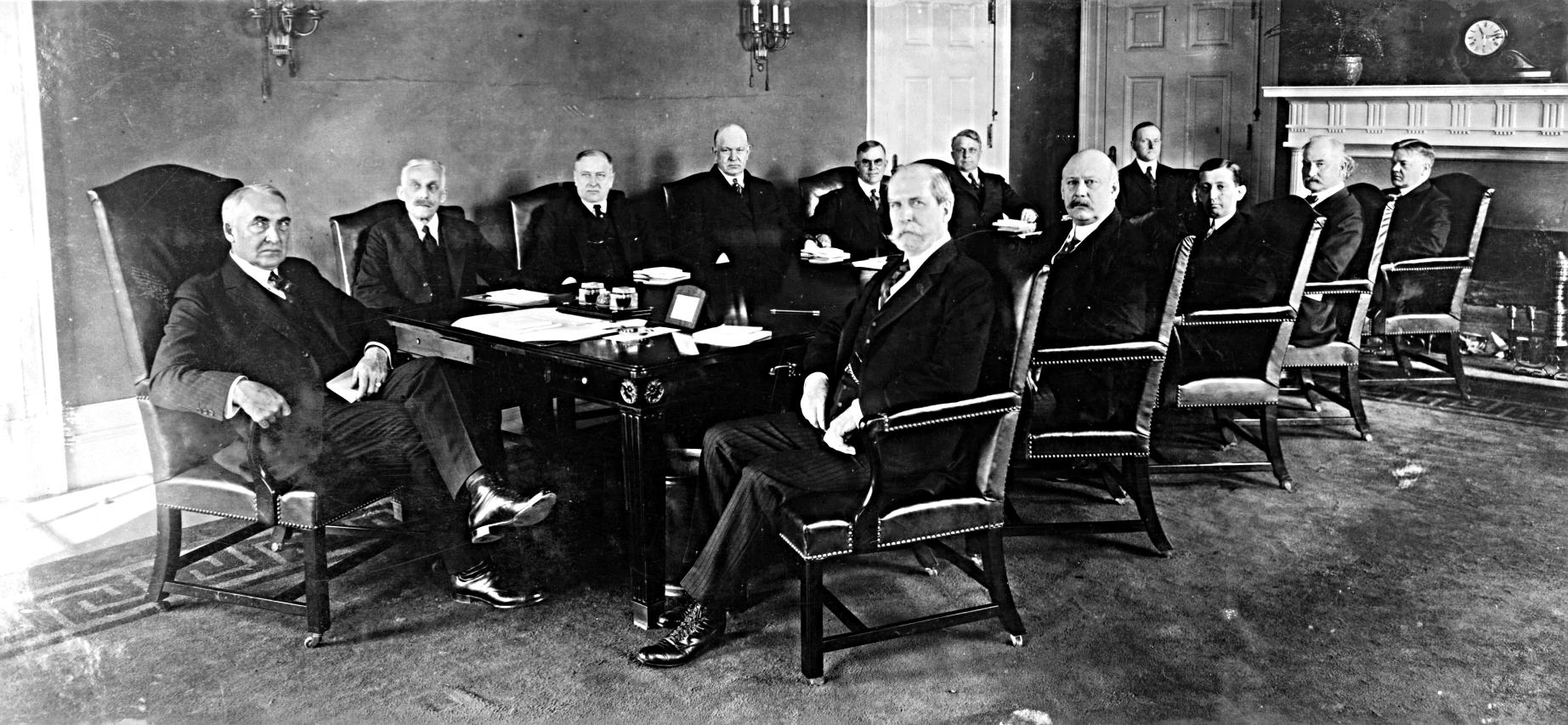

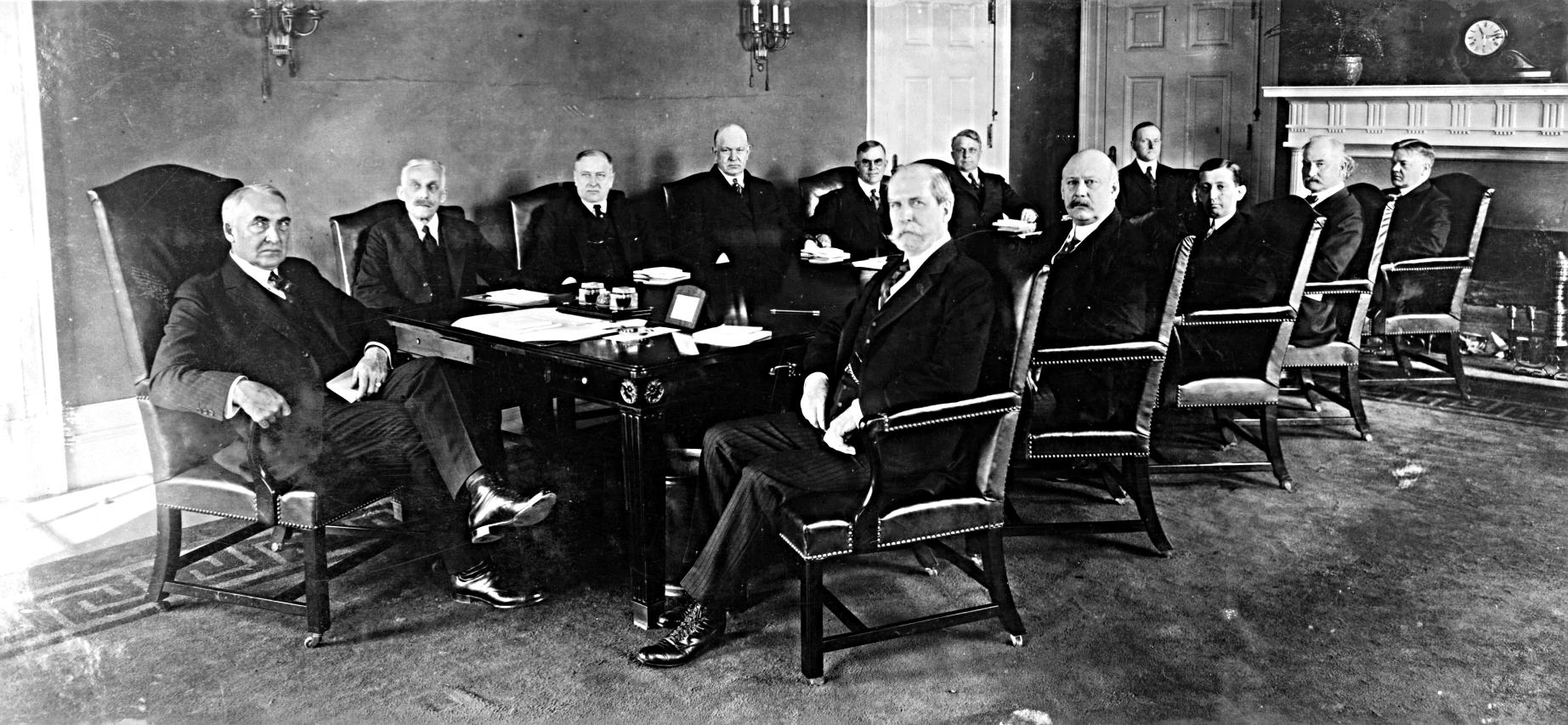

In 1921, newly elected president Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

chose Mellon as his Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

. Mellon would remain in office until 1932, serving under Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, all three of whom were members of the Republican Party. Mellon sought to reform federal taxation in the aftermath of World War I. He argued cutting tax rates on top earners would generate more tax revenue for the government, but otherwise left in place a progressive income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Tax ...

. Some of Mellon's proposals were enacted by the Revenue Act of 1921 and the Revenue Act of 1924

The United States Revenue Act of 1924 () (June 2, 1924), also known as the Mellon tax bill (after U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon) cut federal tax rates for 1924 income. The bottom rate, on income under $4,000, fell from 1.5% to 1 ...

, but it was not until the passage of the Revenue Act of 1926

The United States Revenue Act of 1926, , reduced inheritance and personal income taxes, cancelled many excise imposts, eliminated the gift tax and ended public access to federal income tax returns.

Passed by the 69th Congress, it was signed into ...

that the "Mellon plan" was fully realized. He also presided over a reduction in the national debt, which dropped substantially in the 1920s. Mellon's influence in state and national politics reached its zenith during Coolidge's presidency. Journalist William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 193 ...

noted that "so completely did Andrew Mellon dominate the White House in the days when the Coolidge administration was at its zenith that it would be fair to call the administration the reign of Coolidge and Mellon."

Mellon's national reputation collapsed following the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

and the onset of the Great Depression. Mellon participated in various efforts by the Hoover administration to revive the economy and maintain the international economic order, but he opposed direct government intervention in the economy. After Congress began impeachment proceedings against Mellon, President Hoover shifted Mellon to the position of United States ambassador to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarc ...

. Mellon returned to private life after Hoover's defeat in the 1932 presidential election by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

. Beginning in 1933, the federal government launched a tax fraud investigation on Mellon, leading to a high-profile case that ended with Mellon's estate paying significant sums to settle the matter. Shortly before his death, in 1937, Mellon helped establish the National Gallery of Art. His philanthropic efforts also played a major role in the later establishment of Carnegie Mellon University and the National Portrait Gallery.

Early life and ancestry

Mellon's paternal grandparents, both of whom were Ulster Scots, migrated to the United States fromCounty Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an administrative division for local government but retai ...

, Ireland, in 1818. With their son, Thomas Mellon

Thomas Mellon (February 3, 1813 – February 3, 1908) was an American entrepreneur, lawyer, and judge, best known as the founder of Mellon Bank and patriarch of the Mellon family of Pittsburgh.

Early life

Mellon was born to farmers Andrew Mell ...

, they settled in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania

Westmoreland County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 364,663. The county seat is Greensburg. Formed from, successively, Lancaster, Northumberland, and later Bedford co ...

. Thomas Mellon established a successful legal practice in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, and in 1843 he married Sarah Jane Negley, an heiress descended from some of the first settlers of Pittsburgh. Thomas became a wealthy landowner and real estate speculator, and he and his wife had eight children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Andrew Mellon, the fourth son and sixth child of Thomas and Sarah, was born in 1855. Though he lacked strong convictions about slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, Thomas Mellon became a prominent member of the local Republican Party, and in 1859 he won election to a position on the Pennsylvania court of common pleas

In Pennsylvania, the courts of common pleas are the trial courts of the Unified Judicial System of Pennsylvania (the state court system).

The courts of common pleas are the trial courts of general jurisdiction in the state. The name derives fro ...

. Because Thomas was suspicious of both private and public schools, he built a schoolhouse for his children and hired a teacher; Andrew attended this school beginning at age five.

In 1869, after leaving his judicial position, Thomas Mellon established T. Mellon & Sons, a bank located in Pittsburgh. Andrew joined his father at the bank, quickly becoming a valued employee despite being in his early teens. Andrew also attended Western University (which was later renamed the University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a public state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The university is composed of 17 undergraduate and graduate schools and colleges at its urban Pittsburgh campus, home to the univers ...

), but he never graduated. After leaving Western University, Andrew briefly worked at a lumber and coal business before joining T. Mellon & Sons as a full-time employee in 1873. That same year, the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

devastated the local and national economy, wiping out a portion of the Mellon fortune. With Andrew taking a leading role at T. Mellon & Sons, the bank quickly recovered, and by late 1874 the bank's deposits had reached the level they had been at before the onset of the Panic.

Business career, 1873–1920

Business career, 1873–1898

Mellon's role at T. Mellon & Sons continued to grow after 1873, and in 1876 he was given power of attorney to direct the operations of the bank. That same year, Thomas introduced his son toHenry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a maj ...

, a customer of the bank who would become one of Mellons's closest friends. In 1882, Thomas turned over full ownership of the bank to his son, but Thomas continued to be involved in the bank's activities. Five years later, Mellon's younger brother, Richard B. Mellon, joined T. Mellon & Sons as a co-owner and vice president.

During the 1880s, Mellon began to expand the bank's activities. Along with Frick, Mellon gained control of the Pittsburgh National Bank of Commerce, a national bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:

* a bank owned by the state

* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally (as opposed to regionally or locally or even internationally)

* in the United States, an ordinary p ...

that was authorized to print banknote

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

s. Mellon also acquired or helped found the Union Insurance Company, City Deposit Bank, the Fidelity Title and Trust Company, and the Union Trust Company. He branched out into industrial concerns, becoming a director of the Pittsburgh Petroleum Exchange and a co-founder of two natural gas companies that collectively controlled 35,000 acres of gas lands in the late 1880s. In 1890, Thomas Mellon transferred his properties to Andrew, who would manage the properties on behalf of himself, his parents, and his brothers. In late 1894, Thomas transferred all of his remaining assets to Andrew. Despite the large sums entrusted to Andrew, the businesses he ran were still fairly small in the 1890s; T. Mellon & Sons employed seven individuals in 1895.

In 1889, Mellon agreed to loan $25,000 to the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, a fledgling operation seeking to become the first successful industrial producer of aluminum. Mellon became a director of the company in 1891, and he and Richard played a major role in the establishment of aluminum factories in New Kensington, Pennsylvania

New Kensington, known locally as New Ken, is a city in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. It is situated along the Allegheny River, northeast of Pittsburgh. The population was 12,170 at the 2010 census.

History

Like much of Westmoreland Cou ...

, and Niagara Falls, New York. The company would emerge as one of the most profitable ventures invested in by the Mellons, and in 1907 it was renamed Alcoa.Cannadine (2006), p. 184 Moving into the petroleum industry, the Mellon family also established the Crescent Oil Company, the Crescent Pipeline Company, and the Bear Creek refinery. By 1894, the Mellon family's vertically integrated companies produced ten percent of the oil exported by the United States. Partly due to the difficult economic conditions caused by the onset of the Panic of 1893, in 1895 the Mellons sold their oil interests to Standard Oil. At roughly the same time they were selling their oil concerns, Andrew and Richard invested in the Carborundum Company, a producer of silicon carbide

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder and crystal s ...

. The brothers gained majority ownership of the Carborundum Company in 1898 and replaced the company's founder and president, Edward Goodrich Acheson

Edward Goodrich Acheson (March 9, 1856 – July 6, 1931) was an American chemist. Born in Washington, Pennsylvania, he was the inventor of the Acheson process, which is still used to make Silicon carbide (carborundum) and later a manufacturer of ...

, with a Carnegie protege, Frank W. Haskell. Mellon also invested in mining concerns, becoming vice president of the Trade Dollar Consolidated Mining Company.

Mellon and Henry Clay Frick enjoyed a long-lasting business and social relationship, and Frick frequently hosted Mellon, attorney Philander C. Knox

Philander Chase Knox (May 6, 1853October 12, 1921) was an American lawyer, bank director and politician. A member of the Republican Party, Knox served in the Cabinet of three different presidents and represented Pennsylvania in the United States ...

, inventor George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse Jr. (October 6, 1846 – March 12, 1914) was an American entrepreneur and engineer based in Pennsylvania who created the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry, receiving his first patent at the age ...

, and others for poker games. Frick and Mellon both joined the Duquesne Club

The Duquesne Club is a private social club in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, founded in 1873.

History

The Duquesne Club was founded in 1873. Its first president was John H. Ricketson. The club's present home, a Romanesque structure designed by Lon ...

and, after Frick established the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club was a Pennsylvania corporation which operated an exclusive and secretive retreat at a mountain lake near South Fork, Pennsylvania, for more than fifty extremely wealthy men and their families. The club was ...

, Mellon became one of that club's first members. The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club built the South Fork Dam

The South Fork Dam was an earthenwork dam forming Lake Conemaugh (formerly Western Reservoir, also known as the Old Reservoir and Three Mile Dam, a misnomer), an artificial body of water near South Fork, Pennsylvania, United States. On May 31, 1 ...

, which supported an artificial lake that the club used for boating and fishing. In 1889, the dam broke, causing the Johnstown Flood

The Johnstown Flood (locally, the Great Flood of 1889) occurred on Friday, May 31, 1889, after the catastrophic failure of the South Fork Dam, located on the south fork of the Little Conemaugh River, upstream of the town of Johnstown, Pennsylv ...

, which killed 2,000 people and destroyed 1,600 homes. In the aftermath of the flood, Knox led a legal defense that successfully argued that the club bore no legal responsibility for the flood. Mellon did not publicly comment on the flood, though he did donate $1,000 to a relief fund.

Business career, 1898–1920

By the late 1890s, Mellon had amassed a substantial fortune, but his wealth paled in comparison to that of better-known business leaders such asJohn D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

. In the late 1890s, the Union Trust Company emerged for the first time as one of Mellon's most important and profitable holdings after Mellon broadened the company's activities to include commercial banking. With an infusion of capital from Union Trust, Mellon underwrote the capitalization of National Glass and several other companies. He also became a co-owner of the McClintic-Marshall Construction Company and established Crucible Steel Company, the Pittsburgh Coal Company

The Pittsburgh Terminal Coal Company was a bituminous coal mining company based in Pittsburgh and controlled by the Mellon family. It operated mines in the Pittsburgh Coalfield, including mines in Becks Run and Horning, Pennsylvania. Unusuall ...

, and the Monongahela River Coal Company; the two coal companies collectively contributed 11 percent of the coal production of the United States. With Frick, Richard Mellon, and William Donner, Mellon co-founded Union Steel Company, which specialized in the production of nails and barbed wire. Though Frick had fallen out with steel magnate and long-time business partner Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

, Mellon received Carnegie's consent to venture into the steel industry. Responding to the growing emphasis on naval power in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, Mellon and Frick also became major shareholders in the New York Shipbuilding Corporation

The New York Shipbuilding Corporation (or New York Ship for short) was an American shipbuilding company that operated from 1899 to 1968, ultimately completing more than 500 vessels for the U.S. Navy, the United States Merchant Marine, the United ...

.

In 1902, Mellon reorganized T. Mellon & Sons as the Mellon National Bank, a federally chartered National Bank. Andrew Mellon, Richard Mellon, and Frick drew up a new business arrangement in which the three of them jointly controlled the Union Trust Company, which in turn controlled Mellon National Bank. They also established Union Savings Bank, which accepted deposits by mail, and the Mellon banks flourished in the first years of the 20th century. While Mellon's financial empire prospered, his investments in other areas, including Pittsburgh's streetcar network, the Union Steel Company (which was bought out by U.S. Steel), and the Carborundum Company, also paid off handsomely. Another successful Mellon investment, the

In 1902, Mellon reorganized T. Mellon & Sons as the Mellon National Bank, a federally chartered National Bank. Andrew Mellon, Richard Mellon, and Frick drew up a new business arrangement in which the three of them jointly controlled the Union Trust Company, which in turn controlled Mellon National Bank. They also established Union Savings Bank, which accepted deposits by mail, and the Mellon banks flourished in the first years of the 20th century. While Mellon's financial empire prospered, his investments in other areas, including Pittsburgh's streetcar network, the Union Steel Company (which was bought out by U.S. Steel), and the Carborundum Company, also paid off handsomely. Another successful Mellon investment, the Standard Steel Car Company

The Standard Steel Car Company (SSC) was a manufacturer of railroad rolling stock in the United States that existed between 1902 and 1934.

Established in 1902 in Butler, Pennsylvania by John M. Hansen and "Diamond Jim" Brady, the company quic ...

, was created in partnership with three former U.S. Steel executives. As part of the Texas oil boom

The Texas oil boom, sometimes called the gusher age, was a period of dramatic change and economic growth in the U.S. state of Texas during the early 20th century that began with the discovery of a large oil reserve, petroleum reserve near Beaum ...

, the Mellons also helped J. M. Guffey establish the Guffey Company. The Mellons later removed Guffey as the head of his company, and in 1907 they reorganized the Guffey Company as Gulf Oil

Gulf Oil was a major global oil company in operation from 1901 to 1985. The eighth-largest American manufacturing company in 1941 and the ninth-largest in 1979, Gulf Oil was one of the so-called Seven Sisters oil companies. Prior to its merger ...

and installed William Larimer Mellon Sr. (a son of Andrew Mellon's older brother, James Ross Mellon) as the head of Gulf Oil. The success of Mellon's financial empire and his varied investments made him, according to biographer David Cannadine, the "single most significant individual in the economic life and progress of western Pennsylvania" in the first decade of the 20th century.

The Panic of 1907 devastated several companies based in Pittsburgh, ending a period of strong growth. Some of Mellon's investments experienced a sustained down period after 1907, but most experienced a quick recovery. Mellon also became an investor in George Westinghouse

George Westinghouse Jr. (October 6, 1846 – March 12, 1914) was an American entrepreneur and engineer based in Pennsylvania who created the railway air brake and was a pioneer of the electrical industry, receiving his first patent at the age ...

's Westinghouse Electric Corporation

The Westinghouse Electric Corporation was an American manufacturing company founded in 1886 by George Westinghouse. It was originally named "Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company" and was renamed "Westinghouse Electric Corporation" in ...

after he helped prevent the company from going into bankruptcy. By the end of 1913, Mellon National Bank held more money in deposits than any other bank in Pittsburgh, and the Farmer's Deposit National Bank, which held the second-largest amount of deposits, was controlled by Mellon's Union Trust Company. In 1914, Mellon became a co-owner of Koppers

Koppers is a global chemical and materials company based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States in an art-deco 1920s skyscraper, the Koppers Tower.

Structure

Koppers is an integrated global producer of carbon compounds, chemicals, and trea ...

, which produced a more sophisticated coking oven than the one that had earlier been pioneered by Frick. He also served as a director of various other companies, including the Pennsylvania Railroad and the American Locomotive Company. Mellon was deeply involved in the financing of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, as the Union Trust Company and other Mellon institutions provided millions of dollars in loans to the United Kingdom and France, and Mellon himself invested in Liberty bond

A liberty bond (or liberty loan) was a war bond that was sold in the United States to support the Allied cause in World War I. Subscribing to the bonds became a symbol of patriotic duty in the United States and introduced the idea of financi ...

s.

Old Overholt whiskey

In 1887, Frick, Andrew, and Richard Mellon jointly purchasedOld Overholt

Old Overholt is America's oldest continually maintained brand of whiskey, was founded in West Overton, Pennsylvania, in 1810. Old Overholt is a rye whiskey distilled by A. Overholt & Co., currently a subsidiary of Beam Suntory, which is a sub ...

, a whiskey distillery located in West Overton, Pennsylvania

West Overton is located approximately southeast of Pittsburgh, in East Huntingdon Township, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is on PA 819 between the towns of Mount Pleasant and Scottdale. Its latitude is 40.117N and its lo ...

. At the time, Old Overholt was one of the largest and most respected whiskey producers in the country. In 1907, as prohibition became more popular across the country, Frick and Mellon removed their names from the distilling license but retained ownership in the company. It is believed that Mellon's connections in the Treasury Department are what allowed the company to secure a medicinal permit during Prohibition. This permit allowed Overholt to sell existing whiskey stocks to druggists for medicinal use. When Frick died in December 1919, he left his share to Mellon. In 1925, under pressure from prohibitionists, Mellon sold his share of the company to a New York grocer.

Early involvement in politics

Like his father, Mellon consistently supported the Republican Party, and he frequently donated to state and local party leaders. Through state party bossMatthew Quay

Matthew Stanley "Matt" Quay (September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his death in 1904. Quay's control ...

, Mellon influenced legislators to place high tariffs on aluminum products in the McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

of 1890. During the early 20th century, Mellon was dismayed by the rise of progressivism

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, tec ...

and the antitrust actions pursued by the presidential administrations of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, and Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. He especially opposed the Taft administration's investigations into Alcoa, which in 1912 signed a consent decree rather than going to trial. In the aftermath of World War I, he provided financial support to Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

and other Republicans in their successful campaign to prevent ratification of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

. Mellon attended the 1920 Republican National Convention as a nominal supporter of Pennsylvania Governor William Cameron Sproul

William Cameron Sproul (September 16, 1870 – March 21, 1928) was an American politician from Pennsylvania who served as a Republican member of the Pennsylvania State Senate from 1897 to 1919 and as the 27th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1919 ...

(Mellon hoped Senator Philander Knox would win the nomination), but the convention chose Senator Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

of Ohio as the party's presidential nominee. Mellon strongly approved of the party's conservative platform, and he served as a key fundraiser for Harding during the presidential campaign.

Political career, 1921–1933

Harding administration

Following Harding's victory in the 1920 presidential election, Harding considered various candidates for Secretary of the Treasury, including

Following Harding's victory in the 1920 presidential election, Harding considered various candidates for Secretary of the Treasury, including Frank Lowden

Frank Orren Lowden (January 26, 1861 – March 20, 1943) was an American Republican Party politician who served as the 25th Governor of Illinois and as a United States Representative from Illinois. He was also a candidate for the Republican pres ...

, John W. Weeks, Charles Dawes

Charles Gates Dawes (August 27, 1865 – April 23, 1951) was an American banker, general, diplomat, composer, and Republican politician who was the 30th vice president of the United States from 1925 to 1929 under Calvin Coolidge. He was a co-rec ...

, and, at the urging of Senator Knox, Andrew Mellon. By 1920, Mellon was little-known outside of banking circles, but his potential appointment to the cabinet received strong support from bankers and Pennsylvania Republican leaders like Knox, Senator Boies Penrose

Boies Penrose (November 1, 1860 – December 31, 1921) was an American lawyer and Republican politician from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

After serving in both houses of the Pennsylvania legislature, he represented Pennsylvania in the United ...

, and Governor Sproul. Mellon was reluctant to enter public life due to concerns about privacy and a belief that his ownership of various businesses, including Old Overholt distillery, would be a political liability. But Mellon also wanted to retire from active participation in business, and he saw a cabinet position as a prestigious capstone to his career.

Mellon agreed to accept appointment as Secretary of the Treasury in February 1921, and his nomination was quickly confirmed by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

. Though Mellon's supporters believed that he was highly qualified to address the economic issues facing the country, critics of the Harding administration saw the Mellon appointment as a sign that Harding would "reseat the power of special privileged interests, the powers of avarice and greed, the powers that seek self-aggrandizement at the expense of the general public". Harding paired the nomination of Mellon with that of Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

, who was distrusted by many of the same Senate Republicans who favored Mellon's candidacy. Before joining the cabinet, Mellon sold his banking stock to his brother, Richard, but he continued to hold his non-banking stock. Through Richard and other business associates, Mellon continued to be involved with the major decisions of the Mellon business empire during his time in public service, and he occasionally lobbied congressmen on behalf of his businesses. His fortune continued to grow, and at one point in the 1920s he paid more in federal income tax than any other individual save John Rockefeller and Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

.

As Treasury Secretary, Mellon focused on balancing the budget and paying off World War I debts in the midst of the

As Treasury Secretary, Mellon focused on balancing the budget and paying off World War I debts in the midst of the Depression of 1920–21

Depression may refer to:

Mental health

* Depression (mood), a state of low mood and aversion to activity

* Mood disorders characterized by depression are commonly referred to as simply ''depression'', including:

** Dysthymia, also known as pers ...

; he was largely unconcerned with international affairs and economic matters such as the unemployment rate. To Mellon's chagrin, his department was charged with enforcing Prohibition; he did not believe in teetotaling himself and viewed the law as unenforceable. Aside from balancing the budget, Mellon's top priority was an overhaul of the federal tax code. The income tax had become a major part of the federal government's revenue system with the passage of the Revenue Act of 1913, and federal taxation on income had increased during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

to provide funding for the war effort. According to M. Susan Murnane, major reforms to the federal income tax in the aftermath of World War I were "inevitable", but the exact nature of the tax system in the 1920s was debated by conservatives and progressives within the Republican Party. Unlike the progressives in his party, Mellon rejected the redistributive nature of the taxation system that had been left in place by the Wilson administration. Owing in part to the high debts left over from the war, Mellon did not join with some conservatives in the party, who favored the virtual abolition of the income tax in favor of high tariff rates, excise taxes, a national sales tax, or some combination thereof.

Mellon instead advocated for the retention of a progressive income tax that would serve as an important, but not primary, source of revenue for the federal government. His so-called "scientific taxation" was designed to maximize federal revenue while minimizing the impact on business and industry. The central tenet of Mellon's tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive tax that affected only high-income earners. Mellon argued that such a reduction would minimize tax avoidance and would not affect federal revenue because it would lead to greater economic growth. He hoped that tax reform would encourage high earners to move their savings from tax-exempt state and municipal bonds to taxable, higher yield industrial stocks. Though much of the tax plan that he proposed had been developed by former Wilson administration officials Russell Cornell Leffingwell and Seymour Parker Gilbert, the press generally referred to it as the "Mellon Plan".Murnane (2004), pp. 820–822

The Revenue Act of 1918 had set a top marginal income tax rate of 73% and a corporate tax of approximately 10%. Due in part to the size of the U.S. public debt, which had grown from $1 billion before the war to $24 billion in 1921, the provisions of the Revenue Act of 1918 remained in place when Harding took office. In 1921, the Treasury Department and the

Mellon instead advocated for the retention of a progressive income tax that would serve as an important, but not primary, source of revenue for the federal government. His so-called "scientific taxation" was designed to maximize federal revenue while minimizing the impact on business and industry. The central tenet of Mellon's tax plan was a reduction of the surtax, a progressive tax that affected only high-income earners. Mellon argued that such a reduction would minimize tax avoidance and would not affect federal revenue because it would lead to greater economic growth. He hoped that tax reform would encourage high earners to move their savings from tax-exempt state and municipal bonds to taxable, higher yield industrial stocks. Though much of the tax plan that he proposed had been developed by former Wilson administration officials Russell Cornell Leffingwell and Seymour Parker Gilbert, the press generally referred to it as the "Mellon Plan".Murnane (2004), pp. 820–822

The Revenue Act of 1918 had set a top marginal income tax rate of 73% and a corporate tax of approximately 10%. Due in part to the size of the U.S. public debt, which had grown from $1 billion before the war to $24 billion in 1921, the provisions of the Revenue Act of 1918 remained in place when Harding took office. In 1921, the Treasury Department and the House Ways and Means Committee

The Committee on Ways and Means is the chief tax-writing committee of the United States House of Representatives. The committee has jurisdiction over all taxation, tariffs, and other revenue-raising measures, as well as a number of other progra ...

jointly prepared a bill setting the top marginal rate at the level advocated by Mellon, but opposition in the Senate from progressives like Senator Robert M. La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

limited the size of the tax cuts. In November 1921, Congress passed and Harding signed the Revenue Act of 1921, which raised personal tax exemption

Tax exemption is the reduction or removal of a liability to make a compulsory payment that would otherwise be imposed by a ruling power upon persons, property, income, or transactions. Tax-exempt status may provide complete relief from taxes, redu ...

s and lowered the top marginal tax rate to 58%. Because it differed from his original proposals, Mellon was displeased by the bill. He also strongly disapproved of a "Bonus Bill" passed by Congress that would provide for additional compensation to veterans of World War I, partly because he feared it would interfere with his plans to reduce debt and taxes. With Mellon's support, Harding vetoed the bill, and Congress failed to override the veto.

Coolidge administration

As the economy recovered from recession and began to experience the prosperity of the

As the economy recovered from recession and began to experience the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties

The Roaring Twenties, sometimes stylized as Roaring '20s, refers to the 1920s decade in music and fashion, as it happened in Western society and Western culture. It was a period of economic prosperity with a distinctive cultural edge in the ...

, Mellon emerged as one of the most renowned figures in the Harding administration. One admiring congressman referred to Mellon as the "greatest Secretary of the Treasury since Alexander Hamilton". Harding died after suffering a stroke in August 1923, and he was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge. Mellon enjoyed closer relations with President Coolidge than he had with President Harding, and Coolidge and Mellon shared similar views on most major issues, including the necessity for further tax cuts. William Allen White

William Allen White (February 10, 1868 – January 29, 1944) was an American newspaper editor, politician, author, and leader of the Progressive movement. Between 1896 and his death, White became a spokesman for middle America.

At a 193 ...

, a contemporary journalist, stated that "so completely did Andrew Mellon dominate the White House in the days when the Coolidge administration was at its zenith that it would be fair to call the administration the reign of Coolidge and Mellon."Keller (1982), p. 777

Coolidge, Mellon, business organizations, and administration allies conducted a publicity campaign designed to convince wavering congressmen to support Mellon's tax plan. Their efforts were opposed by the coalition of Democrats and progressive Republicans that exercised effective control over the 68th Congress. In February 1924, the House Ways and Means Committee approved of a bill based on Mellon's plan, but an alliance of progressive Republicans and Democrats engineered passage of an alternative tax bill written by Democrat John Nance Garner; Garner's plan also reduced income taxes but set the top marginal tax rate at 46% rather than Mellon's preferred 33%. In June 1924, Coolidge signed the Revenue Act of 1924

The United States Revenue Act of 1924 () (June 2, 1924), also known as the Mellon tax bill (after U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon) cut federal tax rates for 1924 income. The bottom rate, on income under $4,000, fell from 1.5% to 1 ...

, which contained the income tax rates of Garner's bill and also increased the estate tax

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an es ...

. Coolidge signed the bill but simultaneously called for further tax cuts.Murnane (2004), pp. 833–836, 840–841 Congress also rejected Mellon's proposed constitutional amendment that would have barred the issuance of tax-exempt securities and, over Coolidge's veto, authorized a bonus to World War I veterans. Mellon did, however, win one legislative victory, as he convinced Congress to create the Board of Tax Appeals to adjudicate disputes between taxpayers and the government.

Mellon had originally planned to retire after one presidential term but decided to remain in the cabinet in the hope of presiding over the full enactment of his taxation proposals. In the 1924 presidential election, the Republicans campaigned on further tax cuts, while both the Democrats and third-party candidate Robert La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

denounced Mellon's tax proposals as "a device to relieve multi-millionaires at the expense of other taxpayers". Buoyed by the strong economy, and overcoming the scandals of the Harding years, Coolidge won re-election by a decisive margin. Coolidge saw his victory as a mandate to pursue his favored economic policies, including further tax cuts.

When Congress reconvened after the 1924 elections, it immediately began working on another bill designed to lower tax rates on the highest earners. In February 1926, Coolidge signed the Revenue Act of 1926

The United States Revenue Act of 1926, , reduced inheritance and personal income taxes, cancelled many excise imposts, eliminated the gift tax and ended public access to federal income tax returns.

Passed by the 69th Congress, it was signed into ...

, which reduced the top marginal rate to 25%. Mellon was extremely pleased by the passage of the act, because, unlike the Revenue Act of 1921 and the Revenue Act of 1924, the Revenue Act of 1926 closely reflected Mellon's proposals. In addition to cutting tax rates on top earners, the act also raised the personal exemption for federal income taxes, abolished the gift tax

In economics, a gift tax is the tax on money or property that one living person or corporate entity gives to another. A gift tax is a type of transfer tax that is imposed when someone gives something of value to someone else. The transfer must ...

, reduced the estate tax rate, and repealed a provision that had required the public disclosure of federal income tax returns. Meanwhile, the booming economy fostered a $400 million budget surplus in 1926, and the country's national debt dropped from $24 billion in early 1921 to $19.6 billion at the end of fiscal year 1926. Government revenues increased considerably under Mellon's plan, largely collected from higher-income earners.

With his top priority of tax reform accomplished, Mellon increasingly turned over management of the Treasury Department to his deputy, Ogden L. Mills. After the 1926 elections, Mellon and Mills sought to cut the corporate tax and fully repeal the estate tax. The Revenue Act of 1928 did indeed cut the corporate tax, but the estate tax was left unchanged. Mellon also focused on the construction of new federal buildings, and his efforts led to the construction of several buildings in the Federal Triangle. In 1928, Mellon stated that "in no other nation, and at no other time in the history of the world, have so many people enjoyed such a high degree of prosperity or maintained a standard of living comparable to that which prevails throughout this country today."

Responsibility for foreign relations lay with the State Department rather than the Treasury Department, and Benjamin Strong Jr. and other central bankers took the lead with regard to international monetary policy, but Mellon nonetheless exercised some influence in foreign affairs. He strongly opposed the cancellation of European debts from World War I but recognized that Britain and other countries would be unable to pay those debts without a renegotiation of terms. In 1923, Mellon and British Chancellor of the Exchequer Stanley Baldwin negotiated an agreement in which Britain promised to pay off the debts over a 62-year period. After the adoption of the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following Wor ...

, Mellon reached debt settlements with several other European countries. After protracted negotiations, the United States and France agreed to the Mellon-Berenger Agreement, which reduced France's debt and set terms for repayment.

Hoover administration

1928 election

1928 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1928.

Africa

* 1928 Southern Rhodesian general election

Asia

* 1928 Japanese general election

* 1928 Persian legislative election

* 1928 Philippine House of Representatives elections

* 1928 Philippin ...

, but many conservatives within the party opposed Hoover's candidacy. The conservative resistance to Hoover centered around Mellon, who controlled Pennsylvania's delegation at the 1928 Republican National Convention

The 1928 Republican National Convention was held at Convention Hall in Kansas City, Missouri, from June 12 to June 15, 1928.

Because President Coolidge had announced unexpectedly he would not run for re-election in 1928, Commerce Secretary H ...

and was influential with Republicans throughout the country. Though they had maintained an amicable relationship in public, Mellon privately distrusted Hoover, resented Hoover's engagement in the affairs of other cabinet departments, and feared that a President Hoover would move away from Mellon's tax policies. Several Republicans urged Mellon to run for president, but Mellon believed that he was too old to seek the presidency. Mellon attempted to convince Coolidge or Charles Evans Hughes to run, but neither heeded his appeals. In the months before the 1928 Republican Convention, Mellon maintained his neutrality in the presidential race, but with no compelling alternative Republican candidate willing to run, Mellon finally threw his support behind Hoover. With Mellon's backing, Hoover won the Republican nomination on the first ballot of the convention, and he went on to defeat Al Smith in the 1928 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1928.

Africa

* 1928 Southern Rhodesian general election

Asia

* 1928 Japanese general election

* 1928 Persian legislative election

* 1928 Philippine House of Representatives elections

* 1928 Philippin ...

. Defying widespread expectations that he would retire, Mellon chose to stay on as Secretary of the Treasury. Along with Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

and Secretary of Labor James J. Davis, Mellon is one of only three cabinet members to serve in the same post under three consecutive presidents.

Great Depression

Secretary Mellon had helped persuade the Federal Reserve Board to lower interest rates in 1921 and 1924; lower interest rates contributed to a booming economy, but they also encouraged stock market speculation. In 1928, responding to increasing fears of the dangers of speculation and a booming stock market, the Federal Reserve Board began raising interest rates. Mellon favored another interest rate increase in 1929, and in August 1929 the Federal Reserve Board raised the discount rate to six percent. The higher rate failed to curb speculation, and the activity on the stock market continued to grow. In October 1929, the

Secretary Mellon had helped persuade the Federal Reserve Board to lower interest rates in 1921 and 1924; lower interest rates contributed to a booming economy, but they also encouraged stock market speculation. In 1928, responding to increasing fears of the dangers of speculation and a booming stock market, the Federal Reserve Board began raising interest rates. Mellon favored another interest rate increase in 1929, and in August 1929 the Federal Reserve Board raised the discount rate to six percent. The higher rate failed to curb speculation, and the activity on the stock market continued to grow. In October 1929, the New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE, nicknamed "The Big Board") is an American stock exchange in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed ...

suffered the worst crash in its history in what was called "Black Tuesday

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

". As the vast majority of Americans did not own shares in the stock market, the crash did not immediately have disastrous effects on the U.S. economy as a whole. Mellon had little sympathy for the speculators who lost their money, and he was philosophically opposed to an interventionist economic policy designed to address the stock market crash. Nonetheless, Mellon immediately began calling for cuts to the discount rate, which would reach two percent in mid-1930, and successfully urged Congress to pass a bill providing for temporary, across-the-board tax cuts. Mellon supported the idea of asset liquidation to balance budgets, even if it meant shutting down entire industries.

By mid-1930, many, including Mellon, believed that the economy had already experienced the worst effects of the stock market crash. He did not object to the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act

The Tariff Act of 1930 (codified at ), commonly known as the Smoot–Hawley Tariff or Hawley–Smoot Tariff, was a law that implemented protectionist trade policies in the United States. Sponsored by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willi ...

, which raised tariff rates to one of the highest levels in U.S. history. Despite the optimism of Hoover and Mellon, in late 1930 the economy went into a deep slump, as gross national product declined dramatically and numerous workers lost their jobs. While numerous banks failed, Democrats won control of Congress in the 1930 mid-term elections. As the economy declined, so did Mellon's popularity, which was further damaged by his opposition to another bonus bill for veterans. In mid-1931, the country entered a deep depression and, at Hoover's request, Mellon negotiated a moratorium on German debt repayments. After Mellon returned to the United States in August 1931, he was confronted by another series of bank failures. Among the banks that failed was the Bank of Pittsburgh, the lone remaining major Pittsburgh bank not controlled by the Mellon family. Again following Hoover's lead, Mellon presided over the creation of the National Credit Association, a voluntary initiative among the larger banks that was designed to assist failing institutions. As the National Credit Association proved to be ineffective at stemming the tide of bank failures, Congress and the Hoover administration established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide federal loans to banks.

With the unemployment rate approaching twenty percent, Mellon became one of the most "loathed leaders" in the United States, second only to Hoover himself. Facing this unprecedented economic catastrophe, Mellon urged Hoover to refrain from using the government to intervene in the depression. Mellon believed that economic recessions, such as those that had occurred in 1873 and 1907, were a necessary part of the business cycle because they purged the economy. In his memoirs, Hoover wrote that Mellon advised him to "liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate. Purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. ... enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people."

Facing a large deficit, Mellon and Mills called for a return to the tax rates set by the Revenue Act of 1924 and also sought new taxes on automobiles, gasoline, and other items. Congress responded by passing the Revenue Act of 1932, which included many of the Treasury Department's proposals. In early 1932, Congressman Wright Patman

John William Wright Patman (August 6, 1893 – March 7, 1976) was an American politician. First elected in 1928, Patman served 24 consecutive terms in the United States House of Representatives for Texas's 1st congressional district from 1929 to ...

of Texas initiated impeachment proceedings against Mellon, contending that Mellon had violated numerous federal laws designed to prevent conflicts of interest. Though Mellon had defeated similar investigations in the past, his falling popularity left him unable to effectively counter Patman's charges. Hoover removed Mellon from Washington by offering him the position of ambassador to the United Kingdom. Mellon accepted the post, and Mills replaced his former boss as Secretary of the Treasury.

Mellon arrived in Britain in April 1932, receiving a friendly reception from a country he had often visited over the previous thirty years. From his post, he watched the collapse of the international economic order, including the debt accords that he had helped negotiate. He also convinced the British to allow Gulf Oil to operate in Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

, a British protectorate in the oil-rich region of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

. Defying Mellon's expectations, Hoover was defeated by Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

in the 1932 presidential election. Mellon left office when Hoover's term ended in March 1933, returning to private life after twelve years of government service.

Pennsylvania politics, 1921–1933

Knox and Penrose both died in 1921, leaving a power vacuum in Pennsylvania Republican politics. Along with his nephew, William Larimer Mellon, Mellon became an influential player in Pennsylvania politics, and their support helped ensure the elections of Senator David A. Reed and Senator George W. Pepper in 1922. Mellon was unable to assert the same level of control that Boies Penrose had had over state politics, and his leadership of the state party was challenged byWilliam Scott Vare

William Scott Vare (December 24, 1867August 7, 1934) was an American politician from Pennsylvania who served as a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives for Pennsylvania's 1st congressional district from 1912 to 1927. ...

of Philadelphia and progressive leader Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

, who won the 1922 Pennsylvania gubernatorial election. Nonetheless, Mellon would continue to exert an important influence on Pennsylvania politics throughout the 1920s, especially in senatorial elections and in Allegheny County. Mellon's influence over state politics waned in the early 1930s, as the progressive allies of Governor Pinchot took control of the state Republican Party.

Later life

Numerous financial institutions failed in the months prior to Roosevelt's inauguration, but Mellon National Bank, the Union Trust Company, and another Mellon banking operation, Mellbank Corporation, were all able to avoid closure. Mellon strongly opposed Roosevelt's New Deal policies, especially the1933 Banking Act

The Banking Act of 1933 () was a statute enacted by the United States Congress that established the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and imposed various other banking reforms. The entire law is often referred to as the Glass–Stea ...

, which required separation between commercial and investment banking. Mellon believed that the various New Deal policies, including Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

and unemployment insurance

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a comp ...

, undermined the free market system that had produced one of the largest economies in the world. Aside from banking reform, other New Deal policies, including regulations on utilities and coal mines and laws designed to promote labor unions, also affected Mellon's business empire. Additionally, the Revenue Act of 1934 The Revenue Act of 1934 (May 10, 1934, ch. 277, ) raised United States individual income tax rates marginally on higher incomes. The top individual income tax rate remained at 63 percent.

It was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt ...

and the Revenue Act of 1935 The Revenue Act of 1935, (Aug. 30, 1935), raised federal income tax on higher income levels, by introducing the "Wealth Tax". It was a progressive tax that took up to 75 percent of the highest incomes (over $1 million per year). The Congress separa ...

rescinded many of Mellon's tax policies and contained other provisions that were designed to increase taxation on top earners and corporations.

Even after leaving office, Mellon continued to be vilified by many in the public, and in 1933 Harvey O'Connor published a popular and unfavorable biography, ''Mellon's Millions''. Democrats won effective control of Allegheny County in the 1933 elections, and the following year Democrat Joseph F. Guffey won Pennsylvania's Senate election and George Howard Earle III

George Howard Earle III (December 5, 1890December 30, 1974) was an American politician and diplomat from Pennsylvania. He was a member of the prominent Earle and Van Leer families and the 30th Governor of Pennsylvania from 1935 to 1939. Earle ...

won the state's gubernatorial election. Mellon endured numerous attacks during these campaigns, and his unpopularity in Pittsburgh led him to spend most of his final years in Washington rather than his home town.

In the 1930s, the Roosevelt administration conducted several high-profile tax evasion prosecutions against individuals such as Thomas W. Lamont and Jimmy Walker

James John Walker (June 19, 1881November 18, 1946), known colloquially as Beau James, was mayor of New York City from 1926 to 1932. A flamboyant politician, he was a liberal Democrat and part of the powerful Tammany Hall machine. He was forced t ...

. In response to accusations levied by Republican Congressman Louis Thomas McFadden

Louis Thomas McFadden (July 25, 1876 – October 1, 1936) was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, serving from 1915 to 1935. A banker by trade, he was the chief sponsor of the 1927 McFadden Act ...

of Pennsylvania in early 1933, Attorney General Homer Cummings began an inquiry into Mellon's tax history. Between February 1935 and May 1936, the Board of Tax Appeals heard a widely covered case in which the federal government accused Mellon of tax fraud. During the proceedings, Mellon divulged numerous details of his business career that had previously been unknown to the public.

Mellon was diagnosed with cancer in November 1936. His health declined in 1937, and he died on August 26, 1937. Newspapers across the country took note of his death. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. stated that Mellon had lived through "an epoch in the economic history of the nation, and his passing takes one of the most important industrial and financial figures of our time". Mellon was buried at Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery, Upperville, Virginia

Upperville is a small unincorporated town in Fauquier County, Virginia, United States, along U.S. Route 50 fifty miles from downtown Washington, D.C., near the Loudoun County line. Founded in the 1790s along Pantherskin Creek, it was originally ...

. Months after Mellon's death, the Board of Tax Appeals handed down a ruling exonerating Mellon of all tax fraud charges.

Family

In the early 1880s, Mellon had a serious relationship with Fannie Larimer Jones, but he broke off the relationship after learning that she was suffering fromtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

. After this experience, Mellon refrained from courting women for several years. In 1898, while traveling with Frick and Frick's wife to Europe, Mellon met Nora McMullen, a nineteen-year-old Englishwoman of Ulster Scots ancestry. Mellon visited McMullen's home of Hertford Castle

Hertford Castle was built in Norman times by the River Lea in Hertford, the county town of Hertfordshire, England. Most of the internal buildings of the castle have been demolished. The main surviving section is the Tudor gatehouse, which is a Gr ...

in 1898 and 1899, and, after a period of courtship, Nora married Mellon in 1900. Nora gave birth to a daughter, Ailsa, in 1901. Nora disliked living in Pittsburgh, and she was unhappy in her marriage. By the end of 1903, she had begun an affair with Alfred George Curphey, who would also later be involved with the wife of George Vivian, 4th Baron Vivian

George Crespigny Brabazon Vivian, 4th Baron Vivian (21 January 1878 – 28 December 1940) was a British soldier from the Vivian family who served with distinction in both the Second Anglo-Boer War and World War I.

Early life

He was born at Con ...

. Mellon and Nora eventually reconciled, and in 1907 she gave birth to a son, Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

. The reconciliation proved short-lived, as Nora took up with Curphey again in 1908 and requested a divorce the following year. To avoid a public scandal, Andrew reluctantly agreed to a separation in 1909. Seeking to hold divorce proceedings privately before a judge rather than publicly before a jury, in 1911 Mellon convinced the Pennsylvania legislature to amend a law that had required a jury trial

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are used in a significan ...