Mehmed Talaat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mehmed Talaat (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha,; tr, Talat Paşa, links=no was an Ottoman politician and convicted war criminal of the late Ottoman Empire who served as its leader from 1913 to 1918. Talaat Pasha was chairman of the

The Ottoman Empire was ruled by the sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ran a modern autocracy, complete with a secret police, mass surveillance, and censorship. This autocracy in turn produced a culture of suspicion as well as a spirit of clandestine rebellion in many Ottoman citizens, young Talaat included. He was caught sending a telegram saying "Things are going well. I'll soon reach my goal." He was confronted by the police for this telegram, and claimed that the message was to his dalliance, who defended him. With two of his friends from the post office, he was charged with tampering with the official telegraph and was arrested in 1893.

After being released from prison, he joined the

The Ottoman Empire was ruled by the sultan Abdul Hamid II, who ran a modern autocracy, complete with a secret police, mass surveillance, and censorship. This autocracy in turn produced a culture of suspicion as well as a spirit of clandestine rebellion in many Ottoman citizens, young Talaat included. He was caught sending a telegram saying "Things are going well. I'll soon reach my goal." He was confronted by the police for this telegram, and claimed that the message was to his dalliance, who defended him. With two of his friends from the post office, he was charged with tampering with the official telegraph and was arrested in 1893.

After being released from prison, he joined the

In the 1912 election known as the "election of clubs", Union and Progress won a lopsided victory against the Freedom and Accord Party due to widespread employment of electoral fraud and violence. As a result, Freedom and Accord organized a group in the military known as the

In the 1912 election known as the "election of clubs", Union and Progress won a lopsided victory against the Freedom and Accord Party due to widespread employment of electoral fraud and violence. As a result, Freedom and Accord organized a group in the military known as the

Once Şevket Pasha was out of the picture due to his assassination on 12 July 1913, the CUP established a de facto

Once Şevket Pasha was out of the picture due to his assassination on 12 July 1913, the CUP established a de facto

Throughout the

Throughout the

On 24 April 1915, Talaat Pasha issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople, including

On 24 April 1915, Talaat Pasha issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople, including  Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. He had several conversations with the

Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. He had several conversations with the

On 4 February 1917, Talaat finally replaced

On 4 February 1917, Talaat finally replaced  Many social reforms were introduced, including modernization of the calendar, employment of women as nurses, charitable organizations, in army shops, and in labor battalions behind the front and new faculties in Istanbul University for architecture, arts, and music. One particular piece of controversial social reform was the 1917 " Temporal Family Law" which was a significant advance in

Many social reforms were introduced, including modernization of the calendar, employment of women as nurses, charitable organizations, in army shops, and in labor battalions behind the front and new faculties in Istanbul University for architecture, arts, and music. One particular piece of controversial social reform was the 1917 " Temporal Family Law" which was a significant advance in

Talaat Pasha delivered a farewell speech in the last CUP congress on 1 November, where it was decided to dissolve the party. With Enver, Cemal, Nazım, Şakir, Azmi, and Osman Bedri, he fled the Ottoman capital on a German

Talaat Pasha delivered a farewell speech in the last CUP congress on 1 November, where it was decided to dissolve the party. With Enver, Cemal, Nazım, Şakir, Azmi, and Osman Bedri, he fled the Ottoman capital on a German

The British government exerted diplomatic pressure on the

The British government exerted diplomatic pressure on the

With most CUP leaders in exile, the

With most CUP leaders in exile, the

/ref> Tehlirian admitted to the shooting, but, after a cursory two-day trial, he was found innocent by a German court on grounds of

Many of Talaat's contemporaries wrote of his charm but also of a melancholy spirit. Some occasionally noticed his

Many of Talaat's contemporaries wrote of his charm but also of a melancholy spirit. Some occasionally noticed his

Google Books

* * *

* ttp://www.homepage-link.to/turkey/morgenthau1.html Interview with Talaat Pasha by Henry Morgenthau – American Ambassador to Constantinople 1915br>Talaat Pasha's report on the Armenian GenocideMehmet Talaat (1874–1921) and his role in the Greek Genocide

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Talaat 1874 births 1921 deaths People from Kardzhali People convicted by the Ottoman Special Military Tribunal Pashas People sentenced to death in absentia Assassinated people from the Ottoman Empire Deaths by firearm in Germany 20th-century Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire Recipients of Ottoman royal pardons Committee of Union and Progress politicians Pan-Turkists Ottoman people of World War I Young Turks Treaty of Brest-Litovsk negotiators People from the Ottoman Empire of Pomak descent People assassinated by Operation Nemesis Armenian genocide perpetrators Sayfo perpetrators Government ministers of the Ottoman Empire Political office-holders in the Ottoman Empire People from Edirne Politicians of the Ottoman Empire Turkish nationalists Turkish revolutionaries Talaat Talaat Talaat Pasha Greek genocide perpetrators Murdered criminals

Union and Progress Party

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

, which operated a one-party dictatorship in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and later on became Grand Vizier (Prime Minister) during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He was one of the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

and other ethnic cleansings during his time as Minister of Interior Affairs.

Born in Kırcaali (Kardzhali), Adrianople (Edirne) Vilayet, Mehmed Talaat grew up to despise Sultan Abdul Hamid II's autocracy. He was an early member of the Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP), a secret revolutionary Young Turk organization, and over time became its leader. After the CUP succeeded in restoring the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

and parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

in the 1908 Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

, Talaat was elected as a deputy from Adrianople to the Chamber of Deputies and later became Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

. He played an important role in the downfall of Abdul Hamid the next year during the 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

by organizing a counter government. Multiple crises in the Empire including the 31 March Incident, attacks on Rumelian Muslims in the Balkan Wars, and the power struggle with the Freedom and Accord Party made Talaat and the Unionists disillusioned with multicultural Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, tr, Osmanlıcılık) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the social cohesion needed to keep mille ...

and political pluralism, turning them into hard-line authoritarian Turkish nationalists

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and ...

.

After the 1913 coup and Mahmud Şevket Pasha's assassination, the Ottoman Empire was ruled by Union and Progress in a one-party dictatorship, whose leaders were the triumvirate of Talaat, İsmail Enver, and Ahmed Cemal (known as the Three Pashas

The Three Pashas also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha (1874–1921), the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War ...

), of whom Talaat as its civilian leader was politically most powerful. Talaat and Enver were influential bringing the Ottoman Empire into the First World War. During World War I, he ordered on 24 April 1915 the arrest and deportation of Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

(now Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

), most of them being ultimately murdered, and on 30 May 1915 requested the Temporary Law of Deportation

The Temporary Law of Deportation, also known as the Tehcir Law (; from ''tehcir'', an Ottoman Turkish word meaning "deportation" or "forced displacement" as defined by the Turkish Language Institute), or, officially by the Republic of Turkey, th ...

; these events initiated the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

. He is widely considered the main perpetrator of the genocide, and is thus held responsible for the death of around 1 million Armenians.

In a move that established total Unionist control over the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

, Talaat Pasha became Grand Vizier in 1917, and introduced many social reforms. Talaat personally negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russia's ...

with the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, regaining parts of Eastern Anatolia which were occupied by Russia since 1878, and won the race to Baku on the Caucasus front. However breakthroughs by the Allies in the Macedonia and Palestine fronts meant defeat for the Ottomans and the downfall of the CUP. On the night of 2–3 November 1918, Talaat Pasha and other members of the CUP's central committee fled the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Special Military Tribunal convicted Talaat and sentenced him to death ''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'' for subverting the constitution, profiteering from the war, and organizing massacres against Greeks and Armenians. Exiled in Berlin, he supported the Turkish Nationalists

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and ...

led by Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) in Turkey's War of Independence. He was assassinated in Berlin in 1921 by Soghomon Tehlirian, a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

, as part of Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis () was a program to assassinate both Ottoman perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and officials of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic responsible for the massacre of Armenians during the September Days of 1918 in Baku. Maste ...

.

Early life: 1874–1908

Childhood

Mehmed Talaat was born in 1874 in Kırcaali, Adrianople (Edirne) Vilayet into a middle-class family ofRomani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

and Pomak

Pomaks ( bg, Помаци, Pomatsi; el, Πομάκοι, Pomáki; tr, Pomaklar) are Bulgarian-speaking Muslims inhabiting northwestern Turkey, Bulgaria and northeastern Greece. The c. 220,000 strong ethno-confessional minority in Bulgaria is ...

descent. His father, Ahmet Vasıf, was a kadı from Çeplece, a nearby village. His mother Hürmüz was from a family that migrated from Dedeler village, Kayseri. Talaat also had two sisters. Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018). p.41 Talaat's family fled to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

when their home was occupied by Russian troops during the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war, an experience that contributed to Talaat's nationalism. His father died when Talaat was eleven years old.

Talaat had a powerful build and a dark complexion. His manners were gruff, which caused him to be expelled from the military secondary school at the age of sixteen without a certificate after a conflict with his teacher. Without earning a degree, he joined the staff of a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

company as a postal clerk in Adrianople to provide for his family. His salary was not high, so he worked after hours as a Turkish language

Turkish ( , ), also referred to as Turkish of Turkey (''Türkiye Türkçesi''), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 80 to 90 million speakers. It is the national language of Turkey and Northern Cyprus. Significant sma ...

teacher in the Alliance Israelite School which served the Jewish community of Adrianople. At the age of 21 Talaat was involved in a love affair with the daughter of the Jewish headmaster for whom he worked.

Activism against Abdul Hamid II

Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP), a secret revolutionary Young Turk organization which was agitating against Abdul Hamid's autocracy. In 1896 he was imprisoned for having been part of a CUP cell together with his brother-in-law. Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2018), pp, 44 Sentenced to three years in jail, Talaat was pardoned after serving two years but exiled to Salonika (Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

), where he became a postal clerk in July 1898. Between 1898 and 1908 he served as a postman on the staff of the Salonika Post Office, during which he continued his revolutionary activities in secret. He was promoted to municipal chief clerk in April 1903, following which he could afford to bring his mother and sisters to Salonika. His job in the postal administration gave him the opportunity to smuggle into the city newspapers published by the dissidents abroad.Ahmet Aslan, Türk Basınında Talat Paşa Suikastı ve Yansımaları, ''İstanbul Üniversitesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü Yüksek Lisans Tezi, İstanbul 2010'' Talaat met then economics professor, later friend and CUP Finance Minister Mehmed Cavid

Mehmet Cavit Bey, Mehmed Cavid Bey or Mehmed Djavid Bey ( ota, محمد جاوید بك; 1875 – 26 August 1926) was an Ottoman economist, newspaper editor and leading politician during the dissolution period of the Ottoman Empire. A founding m ...

in Salonika Law School, where he took classes to supplement his lackluster education. The government was still monitoring his activities, and he was almost exiled again to Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

. However the Inspector General for Macedonia Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha

Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha ( ota, حسین حلمی پاشا tr, Hüseyin Hilmi Paşa, also spelled Hussein Hilmi Pasha) (1 April 1855 – 1922) was an Ottoman statesman and imperial administrator. He was twice the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empir ...

was partial towards the secret committee and intervened, and Talaat returned to Salonika to work as a school principal.

In September 1906, the Ottoman Freedom Committee (OFC) was formed as another secret Young Turk organization based in Salonika. The founders of the OFC included Talaat, the CUP's future general secretary Dr. Midhat Şükrü, Mustafa Rahmi, and İsmail Canbulat. Many officers of the Third Army were recruited into the OFC, including the future heroes of the revolution Ahmed Niyazi and İsmail Enver. Under Talaat's initiative, the Salonika-based OFC merged with Ahmet Rıza

Ahmet Rıza Bey (1858 – 26 February 1930) was an Ottoman-born Turkish politician, educator, and a prominent member of the Young Turks, during the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. He was also a key early leader of the Committee ...

's Paris-based CUP in September 1907, and the group became the internal center of the CUP in the Ottoman Empire. Talaat was briefly secretary-general

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the internal CUP, while Bahattin Şakir Baha al-Din or Bahaa ad-Din ( ar, بهاء الدين, Bahāʾ al-Dīn, splendour of the faith), or various variants like Bahauddin, Bahaeddine or (in Turkish) Bahattin, may refer to:

Surname

* A. K. M. Bahauddin, Bangladeshi politician and the M ...

was secretary-general of the external CUP. After the revolution, Talaat's more radical and militant internal CUP would see themselves supplant the older cadre of Young Turks that was Rıza's network of exiles.

Rise to power: 1908–1913

Young Turk Revolution and aftermath

The Unionists found themselves at the behest of a spontaneous revolution in 1908, which commenced with Niyazi and Enver's flight into the Albanian hinterlands. Talaat's role during theYoung Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

was to organize a plot to assassinate the garrison commander of Salonika, Ömer Nazım, who was a Hamidian loyalist and spy master of the area. Nazım survived his hired '' Fedai'' with injury, but the incident, as well as other assassinations carried out by the CUP during the revolution, intimidated the Hamidian establishment enough to reopen the parliament and reinstate the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. For the first time in three decades, an election was held for the Chamber of Deputies, which this time featured political parties. Talaat was easily elected into parliament as Union and Progress's candidate for deputy of Adrianople, and then was elected the parliament's vice-president. Talaat was the most important politician in the Ottoman Empire between 1908 and 1918.

A year later in the 31 March Incident

The 31 March Incident ( tr, 31 Mart Vakası, , , or ) was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Pr ...

, what started out as an anti-Unionist demonstration in the capital quickly turned into an anticonstitutionalist-monarchist counter revolution where Abdul Hamid attempted to reestablish his autocracy. The Grand Vizier Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha was forced to resign for Ahmed Tevfik Pasha. Khachatur Malumian

Khachatur Malumian ( hy, Խաչատուր Մալումյան), also known as Edgar Aknuni (''Aknouni or Agnouni''; hy, Էտկար Ակնունի) (1863 in Meghri, Russian Empire – 1915) was an Armenian journalist and political activist. ...

, leader of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

(ARF), hid Talaat and Dr. Nazım in his house while mob violence targeted MPs. Three days later, Talaat and 100 MPs escaped Constantinople for Ayastefanos (Yeşilköy

(; meaning "Green Village"; prior to 1926, San Stefano or Santo Stefano el, Άγιος Στέφανος, Ágios Stéfanos, tr, Ayastefanos) is an affluent neighbourhood ( tr, mahalle) in the district of Bakırköy, Istanbul, Turkey, on the M ...

) to organize a separate national assembly from the volatile situation in Constantinople, and declared the change in government illegal. Relief came in the form of pro-constitutionalist forces known as the Action Army

The Action Army ( tr, Ḥareket Ordusu), also translated as the Army of Action, was a force formed by elements of the Ottoman Army sympathetic to the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) during the 31 March Incident, sometimes referred to as the ...

led by Mahmud Şevket Pasha, which stopped in Ayastefanos before marching on the capital; it was secretly agreed there that Abdul Hamid would be replaced by his brother. After the reactionary revolt was crushed, Talaat bullied the Shaykh al-Islam Sahip Molla to get a fatwa for Abdul Hamid's deposition, and convinced Tevfik Pasha to step down and return Hilmi Pasha to the premiership. With the fatwa, the parliament voted to depose Abdul Hamid II. Talaat and Ahmed Muhtar Pasha

Ahmed Muhtar Pasha ( ota, احمد مختار پاشا; 1 November 1839 – 21 January 1919) was a prominent Ottoman field marshal and Grand Vizier, who served in the Crimean and Russo-Turkish wars. Ahmed Muhtar Pasha was appointed as ...

headed the delegation to announce to Prince Reşad of his ascension to the throne.

In August 1909 Mehmed Talaat led a 17-member parliamentary delegation to Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

. He learned there that he was appointed Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

in Hilmi Pasha's cabinet reshuffle, becoming the second Unionist with a cabinet position (first being Cavid as Finance Minister

A finance minister is an executive or cabinet position in charge of one or more of government finances, economic policy and financial regulation.

A finance minister's portfolio has a large variety of names around the world, such as "treasury", ...

). He continued Hamidian era anti-Zionist restrictions in Ottoman Palestine

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

, as well as enforce imperial rule in revolting provinces like Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares ...

and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

. That year, Louis Rambert, director of the Régie des Tabacs, wrote that Talaat was "the acknowledged head of the Committee of Union and Progress and the Young Turks." Biographer Hans-Lukas Kieser

Hans-Lukas Kieser (born 1957) is a Swiss historian of the late Ottoman Empire and Turkey, Professor of modern history at the University of Zurich and president of the Research Foundation Switzerland-Turkey in Basel. He is an author of books and ar ...

writes that he was under the influence of Bahattin Şakir Baha al-Din or Bahaa ad-Din ( ar, بهاء الدين, Bahāʾ al-Dīn, splendour of the faith), or various variants like Bahauddin, Bahaeddine or (in Turkish) Bahattin, may refer to:

Surname

* A. K. M. Bahauddin, Bangladeshi politician and the M ...

and Mehmed Nazım before 1908, but after late 1909 he had an increased interest in the new Central Committee member Ziya Gökalp

Mehmet Ziya Gökalp (23 March 1876 – 25 October 1924) was a Turkish sociologist, writer, poet, and politician. After the 1908 Young Turk Revolution that reinstated constitutionalism in the Ottoman Empire, he adopted the pen name Gökalp ("ce ...

and his more revolutionary and Pan-Turkist

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), with its aim bei ...

ideas.

Due to an increasingly toxic political climate, Talaat stepped down as Interior Minister in March 1911 for his fellow committee-man Halil Menteşe

Halil Menteşe (1874–1948) was a Turkish government minister and politician, who was a well known official of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). He was the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the President of the Chamber of Deputies in th ...

. For a short time he was Minister of Post and Telegraph in January 1912.

Crisis for the committee

In the 1912 election known as the "election of clubs", Union and Progress won a lopsided victory against the Freedom and Accord Party due to widespread employment of electoral fraud and violence. As a result, Freedom and Accord organized a group in the military known as the

In the 1912 election known as the "election of clubs", Union and Progress won a lopsided victory against the Freedom and Accord Party due to widespread employment of electoral fraud and violence. As a result, Freedom and Accord organized a group in the military known as the Savior Officers

Savior or Saviour may refer to:

*A person who helps people achieve salvation, or saves them from something

Religion

* Mahdi, the prophesied redeemer of Islam who will rule for seven, nine or nineteen years

* Maitreya

* Messiah, a saviour or li ...

to bring down the CUP dominated legislature. Talaat urged for Şevket Pasha, who was appointed Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

after the 31 March Incident, to resign as in the lead-up to the coup d'état, something he wrote that he regretted once Şevket Pasha did so in support of the Savior Officers. Eventually, pro-CUP Grand Vizier Said Pasha had to acquiesce to the Savior Officers demands, and the parliament was dissolved with a new election to take place in autumn of 1912. It was no longer safe for Unionists to be in the open, and it was plausible that the CUP would be banned by the government. Talaat had to once again lay low, hiding with Midhat Şükrü, Hasan Tahsin, and Cemal Azmi in Tahsin's brother-in-law's house. By 1912 Talaat definitely abandoned the belief that constitutionalism and rule of law could unite the multi-ethnic and fragmented " Ottoman nation", which was the original ''raison d'être'' of the Young Turks, and turned to more radical politics. He and other high ranking CUP leaders organized and gave speeches in a pro-war rally against the Balkan nations in Sultanahmet Square before the Balkan Wars broke out.

The Savior Officer-backed government of Ahmed Muhtar Pasha

Ahmed Muhtar Pasha ( ota, احمد مختار پاشا; 1 November 1839 – 21 January 1919) was a prominent Ottoman field marshal and Grand Vizier, who served in the Crimean and Russo-Turkish wars. Ahmed Muhtar Pasha was appointed as ...

fell soon after when the Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

achieved decisive victory over the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

. Talaat volunteered for the war, but was dismissed from the army for distributing political propaganda. The CUP's headquarters in Salonika had to be relocated to Constantinople when the city fell to Greece, while his hometown of Adrianople was besieged by the Bulgarians. The imperial capital swelled with Rumelian Muslims refugees that were expelled from the Balkans. The scheduled election had to be canceled, and Kâmil Pasha

Mehmed Kâmil Pasha ( ota, محمد كامل پاشا مصري زاده; tr, Kıbrıslı Mehmet Kâmil Paşa, "Mehmed Kamil Pasha the Cypriot"), also spelled as Kiamil Pasha (1833 – 14 November 1913), was an Ottoman statesman and liberal poli ...

's government started peace negotiations with the Balkan League in December. Following rumors that the government was willing to surrender Adrianople which was still under siege, Talaat and Enver began plotting a coup. The coup launched on 23 January 1913, known as the Raid on the Sublime Porte

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

, succeeded in overthrowing the government, with Kâmil Pasha and his cabinet resigning for Mahmud Şevket Pasha's national unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other nat ...

which this time included the CUP, and resumed fighting. Talaat and Enver urged Şevket Pasha to accept the Grand Vezierate, but mutual distrust between the generalissimo and the committee meant Talaat only came back as deputy Interior Minister, so he employed ''komiteci'' politics to stay influential. He urged for the Empire to continue fighting in the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

to relieve Adrianople, as well as order the arrests against leading Freedom and Accord members and journalists in the subsequent state of emergency. However, with demands from the great powers to surrender Adrianople and a deteriorating military situation, Şevket Pasha and the CUP finally acknowledged defeat.

Union and Progress regime: 1913–1918

Consolidating power

Once Şevket Pasha was out of the picture due to his assassination on 12 July 1913, the CUP established a de facto

Once Şevket Pasha was out of the picture due to his assassination on 12 July 1913, the CUP established a de facto one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

in the Ottoman Empire. Talaat returned as interior minister in Said Halim Pasha's cabinet. He kept this post until the CUP's fall from power following the Ottoman Empire's surrender in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1918. Talaat, with Enver and commandant Ahmet Cemal

Ahmed Djemal ( ota, احمد جمال پاشا, Ahmet Cemâl Paşa; 6 May 1872 – 21 July 1922), also known as Cemal Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one of the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I.

Djemal wa ...

, formed a group later known as the Three Pashas

The Three Pashas also known as the Young Turk triumvirate or CUP triumvirate consisted of Mehmed Talaat Pasha (1874–1921), the Grand Vizier (prime minister) and Minister of the Interior; Ismail Enver Pasha (1881–1922), the Minister of War ...

. These men were a triumvirate

A triumvirate ( la, triumvirātus) or a triarchy is a political institution ruled or dominated by three individuals, known as triumvirs ( la, triumviri). The arrangement can be formal or informal. Though the three leaders in a triumvirate are ...

that ran the Ottoman government until the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in October 1918. However historian Hans-Lukas Kieser asserts that this state of rule by triumvirate was accurate for only the years 1913–1914, and thereafter Talaat was the sole dictator of the Ottoman Empire, especially once he became Grand Vizier in 1917. Erik Jan Zürcher instead asserts a rule of diarchy, with Talaat leader of the civilian government and Enver the military, especially after Cemal Pasha's dispatch to Syria. Kieser asserts his Ottoman Empire was not a totalitarian state, but a balance of many factions maintained through kickbacks and corruption. Strong governors had much maneuverability to themselves, provided they execute Talaat and the central committee's new Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

programmes.

That summer came Bulgaria's attack on Greece and Serbia, starting the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies r ...

. Talaat was able to procure an important loan from the Régie to ensure success in retaking Adrianople. The Ottomans soon joined the war, retaking the city even though the great powers had forced the Ottomans to surrender Adrianople only months earlier. Talaat symbolically joined the army and took part in the recapture. This was a failure of diplomacy by the great powers; for Talaat and the committee, this moment made them learn to not take international diplomacy seriously if the situation on the ground reflected otherwise. He led the negotiations with Bulgaria in the Constantinople conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( tr, Tersane Konferansı "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constan ...

, which resulted in a population exchange and formalizing Ottoman reassertion of sovereignty over Adrianople. Talaat would negotiate another peace with Greece too. This peace was very tenuous however, as Talaat, Enver Pasha, and Mahmud Celal (Bayar), secretary of the local CUP branch, organized the deportations of Rûm in the Smyrna Vilayet, which almost started a war with Greece. Talaat was confronted by the sultan when the sultan learned of the deportations , but insisted that the stories of persecution of Rûm

Rūm ( ar, روم , collective; singulative: Rūmī ; plural: Arwām ; fa, روم Rum or Rumiyān, singular Rumi; tr, Rûm or , singular ), also romanized as ''Roum'', is a derivative of the Aramaic (''rhπmÈ'') and Parthian (''frwm'') ...

were fabricated by the Empire's enemies.

Between 1911 and 1914 the Ottoman Empire negotiated with the European powers and the ARF

ARF may refer to:

Organizations

* Advertising Research Foundation

* Animal Rescue Foundation

* Armenian Revolutionary Federation

* ASEAN Regional Forum

People

* Cahit Arf (1910–1997), Turkish mathematician

Science, medicine, and mathematics

* ...

on reform in the East. He attended multiple meetings with leading Armenian politicians Krikor Zohrab

Krikor Zohrab ( hy, Գրիգոր Զոհրապ; 26 June 1861 – 1915) was an influential Armenian writer, politician, and lawyer from Constantinople (now Istanbul). At the onset of the Armenian genocide he was arrested by the Turkish government an ...

, Karekin Pastermadjian

Garegin or Karekin Pastermadjian ( classical hy, Գարեգին Փաստրմաճեան), better known by his '' nom de guerre'' Armen Garo or Armen Karo (Արմէն Գարօ; 9 February 1872 – 23 March 1923) was an Armenian activist and p ...

, Bedros Hallachian, and Vartkes Serengülian

Vartkes Serengülian ( hy, Վարդգէս Սէրէնկիւլեան; also known as Hovhannes hy, Յովհաննէս or Gisak) (1871, Erzurum – 1915, Urfa), was an Ottoman Armenian political and social activist, and a member of Ottoman Parl ...

, however lack of trust between the old allies of the committee and the ARF and growing radicalism within the CUP slowed negotiations. Under overwhelming diplomatic pressure, a reform package was finally produced in December 1914, but it would be soon terminated under wartime conditions and an about-face by the committee on the Armenian question. On 6 September, Talaat Pasha sent a telegram to the governors of Hüdâvendigâr ( Bursa), İzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey. It is located at the Gulf of İzmit in the Sea of Marmara, about east of Istanbul, on the northwestern part of Anatolia.

As of the last 31/12/2019 estimation, the ...

, Canik, Adrianople, Adana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, wh ...

, Aleppo, Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

, Bitlis

Bitlis ( hy, Բաղեշ '; ku, Bidlîs; ota, بتليس) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Bitlis Province. The city is located at an elevation of 1,545 metres, 15 km from Lake Van, in the steep-sided valley of the Bitlis R ...

, Van, Sivas

Sivas (Latin and Greek: ''Sebastia'', ''Sebastea'', Σεβάστεια, Σεβαστή, ) is a city in central Turkey and the seat of Sivas Province.

The city, which lies at an elevation of in the broad valley of the Kızılırmak river, is ...

, Mamuretülaziz (Elazığ

Elazığ () is a city in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey, and the administrative centre of Elazığ Province and Elazığ District. It is located in the uppermost Euphrates valley. The plain on which the city extends has an altitude of . ...

), and Diyarbekir to prepare for the arrests of Ottoman Armenian

Armenians in the Ottoman Empire (or Ottoman Armenians) mostly belonged to either the Armenian Apostolic Church or the Armenian Catholic Church. They were part of the Armenian millet until the Tanzimat reforms in the nineteenth century equa ...

citizens. Armenians and Assyrians within the Empire began organising themselves into militias

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

to protect themselves as the Special Organisation, a Unionist paramilitary, started harassing them.

Entering World War I

Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era ( ota, ایكنجی مشروطیت دورى; tr, İkinci Meşrutiyet Devri) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 dissolution of the ...

, the Ottoman Empire was diplomatically isolated, which it paid for dearly through territorial losses in the Balkans. Therefore, on 9 May, Talaat and Ahmet İzzet Pasha

Ahmad ( ar, أحمد, ʾAḥmad) is an Arabic male given name common in most parts of the Muslim world. Other spellings of the name include Ahmed and Ahmet.

Etymology

The word derives from the root (ḥ-m-d), from the Arabic (), from the ve ...

met with Czar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

and Sergei Sazanov to propose an alliance with Russia, which ended up falling through. Talaat, Enver, and Halil Halil is a common Turkish male given name. It is equivalent to the Arabic given name and surname Khalil or its variant Khaleel.

Notable persons with the name include:

* Halil Akbunar (born 1993), Turkish footballer

* Halil Akkaş (born 1983), ...

were successful in securing a secret alliance with Germany during the July Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, which led to the outbreak of World War I (1914–1918). The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Pri ...

. Following the sale of the '' Goeben'' and '' Breslau'' to the Ottoman Empire, the three convinced Cemal Pasha to agree to a naval strike against Russia. The resulting declarations of war saw many resign from the government, including Cavid, which saddened Talaat. He became finance minister in Cavid's place.

With the expectation that the new war would free the Empire of its constraints on its sovereignty by the great powers, Talaat went ahead with accomplishing major goals of the CUP; unilaterally abolishing the centuries-old Capitulations, prohibiting foreign postal services, terminating Lebanon's autonomy, and suspending the reform package for the Eastern Anatolian provinces that had been in effect for just seven months. This unilateral action prompted a joyous rally in Sultanahmet Square.

Talaat and his committee hoped to save the Ottoman Empire by quickly and decisively establishing Turan

Turan ( ae, Tūiriiānəm, pal, Tūrān; fa, توران, Turân, , "The Land of Tur") is a historical region in Central Asia. The term is of Iranian origin and may refer to a particular prehistoric human settlement, a historic geographical re ...

by capitalizing on the declaration of Jihad. But Enver Pasha's decisive defeat in Sarikamish and Cemal Pasha's failure to take Suez meant Talaat had to come to terms with the reality on the ground, which made him fall into a depression. He worked to keep morale afloat on the crumbling Caucasian front by relaying false information of successes in wars in the Balkans which weren't even happening.

Armenian genocide

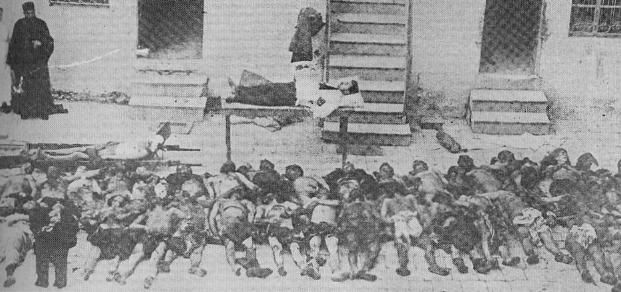

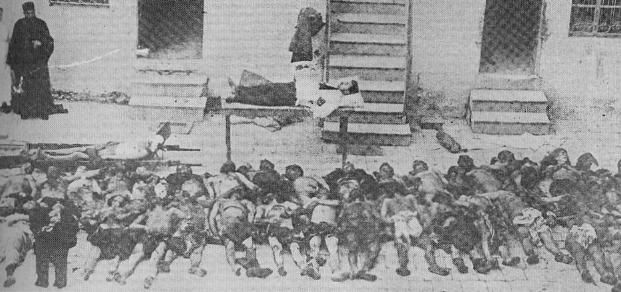

A report presented to Talaat and Cevdet Bey (governor of Van Vilayet) by ARF membersArshak Vramian

Arshak Vramian ( hy, Արշակ Վռամյան, Arshag Vramian, born Onnik Derdzakian; 1871 – 4 April 1915) was an Armenian revolutionary and a leading member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation; he was a member of the party's Central Commi ...

and Vahan Papazian on atrocities committed by the Special Organisation against Armenians in Van created more friction between the two organisations. However, the Unionists were still not yet confident enough to purge Armenians from politics or pursue policies of ethnic engineering. Victory of the defence of the Bosphorus on 18 March though galvanized Talaat, and he decided to take action by starting the machinations of the destruction of Christian minorities in the Ottoman Empire. On 24 April 1915, Talaat Pasha issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople, including

On 24 April 1915, Talaat Pasha issued an order to close all Armenian political organizations operating within the Ottoman Empire and arrest Armenians connected to them, justifying the action by stating that the organizations were controlled from outside the empire, were inciting upheavals behind the Ottoman lines, and were cooperating with Russian forces. This order resulted in the arrest on the night of 24–25 April 1915 of 235 to 270 Armenian community leaders in Constantinople, including Dashnak

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

and Hunchak

The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (SDHP) ( hy, Սոցիալ Դեմոկրատ Հնչակյան Կուսակցություն; ՍԴՀԿ, translit=Sots’ial Demokrat Hnch’akyan Kusakts’ut’yun), is the oldest continuously-operating Armenian ...

politicians, clergymen, physicians, authors, journalists, lawyers, and teachers, the majority of whom were eventually murdered, including his colleagues Zohrab and Serengülian. Although the mass killings of Armenian civilians had begun in Van several weeks earlier, these mass arrests in Constantinople are considered by many commentators to be the start of the Armenian genocide.

He then issued the order for the Tehcir Law

The Temporary Law of Deportation, also known as the Tehcir Law (; from ''tehcir'', an Ottoman Turkish word meaning "deportation" or "forced displacement" as defined by the Turkish Language Institute), or, officially by the Republic of Turkey, the ...

of 1 June 1915 to 8 February 1916 that allowed for the mass deportation of Armenians, a principal means of carrying out what is now recognized as a genocide against Armenians. The deportees did not receive any humanitarian assistance and there is no evidence that the Ottoman government provided the extensive facilities and supplies that would have been necessary to sustain the life of hundreds of thousands of Armenian deportees during their forced march to the Syrian Desert or after. Meanwhile, the deportees were subject to periodic rape and massacre. Talaat, who was a telegraph operator from a young age, had installed a telegraph machine in his own home and sent "sensitive" telegrams during the course of the deportations. This was confirmed by his wife Hayriye, who stated that she often saw him using it to give direct orders to what she believed were provincial governors.

Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. He had several conversations with the

Numerous diplomats and notable figures confronted Talaat Pasha over the deportations and news of massacres. He had several conversations with the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

ambassador, Henry Morgenthau, Sr.

Henry Morgenthau (; April 26, 1856 – November 25, 1946) was a German-born American lawyer and businessman, best known for his role as the ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Morgenthau was one of the most prominent Americans w ...

On 2 August 1915 Talaat told him that "that our Armenian policy is absolutely fixed and that nothing can change it. We will not have the Armenians anywhere in Anatolia. They can live in the desert but nowhere else." In another exchange, he demanded from Morgenthau the list of the holders of American insurance policies belonging to Armenians in an effort to appropriate the funds to the state. Morgenthau refused. Talaat told him in a later conversation that:

Talaat believed Armenian deportation avenged the Muslim expulsions of the Balkan Wars, and resettled Muhacir

Muhacir or Muhajir (from ar, مهاجر, translit=muhājir, lit=migrant) are the estimated 10 million Ottoman Muslim citizens, and their descendants born after the onset of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, mostly Turks but also Albanians ...

in abandoned Armenian property.

The Assyrian Christian community was also targeted by the Unionist government in what is now known as the Seyfo

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish ...

. Talaat ordered the governor of Van to remove the Assyrian population in Hakkâri, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, however this anti-Assyrian policy couldn't be implemented nationally.

Meanwhile, deportations of the Rûm

Rūm ( ar, روم , collective; singulative: Rūmī ; plural: Arwām ; fa, روم Rum or Rumiyān, singular Rumi; tr, Rûm or , singular ), also romanized as ''Roum'', is a derivative of the Aramaic (''rhπmÈ'') and Parthian (''frwm'') ...

were put on hold as Germany wished for a Greek ally or neutrality, however for the sake of their alliance, German reaction to the deportations of Armenians was muted. The participation of the Ottoman Empire as an ally against the Entente powers

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

was crucial to German grand strategy in the war, and good relations were needed. Following Russian breakthrough in the Caucasus and signs that Greece would side with the Allied powers after all, the CUP was finally able to resume operations against the Greeks of the empire, and Talaat ordered the deportation of the Pontus Greeks of the Black Sea coast.

Talaat was also a leading force in the Turkification

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

and deportation of Kurds. In May 1916 he mandated Kurds be deported to the western region of Anatolia, and prohibited the resettlement of Kurds to the south in order to prevent Kurds from becoming Arabized

Arabization or Arabisation ( ar, تعريب, ') describes both the process of growing Arab influence on non-Arab populations, causing a language shift by the latter's gradual adoption of the Arabic language and incorporation of Arab culture, aft ...

. He was a major force behind the policies regarding the resettlement of Kurds and wanted to be informed of whether the Kurds would really be turkified or not and how they got along with the Turkish inhabitants in the areas where they had been resettled too. Talaat outlined that nowhere in the Empire's vilayets should the Kurdish population be more than 5%. To that end, Balkan Muslim and Turkish refugees were prioritised to be resettled in Urfa

Urfa, officially known as Şanlıurfa () and in ancient times as Edessa, is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Şanlıurfa Province. Urfa is situated on a plain about 80 km east of the Euphrates River. Its climate features ex ...

, Maraş, and Antep

Gaziantep (), previously and still informally called Aintab or Antep (), is a major city and capital of the Gaziantep Province, in the westernmost part of Turkey's Southeastern Anatolia Region and partially in the Mediterranean Region, approximat ...

, while some Kurds were deported to Central Anatolia. Kurds were also supposed to be resettled in abandoned Armenian property, however negligence by resettlement authorities still resulted in the deaths of many Kurds by famine.

Approximately 1.7 million Christians (including 200,000 Greeks and 100,000 Lebanese Christians and Druze) died during World War I and the total Ottoman war deaths of some 3.7 million amounted to 14% of the prewar population. According to the Ottoman Interior Ministry, the population of Ottoman Armenians decreased to 284,000 from 1,256,000.

Premiership

On 4 February 1917, Talaat finally replaced

On 4 February 1917, Talaat finally replaced Said Halim Pasha

Mehmed Said Halim Pasha ( ota, سعيد حليم پاشا ; tr, Sait Halim Paşa; 18 or 28 January 1865 or 19 February 1864 – 6 December 1921) was an Ottoman statesman of Albanian originDanişmend (1971), p. 102 who served as Grand Vizier o ...

(a puppet of the committee anyway) by becoming the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, while also retaining the Ministry of the Interior. This made him the first member of parliament to become a Prime Minister in Ottoman (and Turkish) history. This move completed the Unionist party-state, as he was both Grand Vizier and chairman of the Union and Progress Party.

On 15 February, Talaat Pasha gave a speech to parliament of his program, expressing his will to reform to bring Ottoman society on par with European civilization. Like first president of the succeeding republic, Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), would later say similarly, Talaat Pasha believed that there was "only one civilization in the world urope nd that Turkeyto be saved, must be joined to civilization." Another point brought up was cracking down on corruption, much of which he was responsible for and never followed through with.

Many social reforms were introduced, including modernization of the calendar, employment of women as nurses, charitable organizations, in army shops, and in labor battalions behind the front and new faculties in Istanbul University for architecture, arts, and music. One particular piece of controversial social reform was the 1917 " Temporal Family Law" which was a significant advance in

Many social reforms were introduced, including modernization of the calendar, employment of women as nurses, charitable organizations, in army shops, and in labor battalions behind the front and new faculties in Istanbul University for architecture, arts, and music. One particular piece of controversial social reform was the 1917 " Temporal Family Law" which was a significant advance in women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

and secularism in Ottoman matrimonial law

Marriage law refers to the legal requirements that determine the validity of a marriage, and which vary considerably among countries. See also Marriage Act.

Summary table

Rights and obligations

A marriage, by definition, bestows ...

. When it came to religious reform, the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

was translated into (Ottoman) Turkish, and even the call to prayer

A call to prayer is a summons for participants of a faith to attend a group worship or to begin a required set of prayers. The call is one of the earliest forms of telecommunication, communicating to people across great distances. All religions ...

was held in Turkish in a few select mosques in the capital. These pre-Kemalist secularisation and modernisation reforms paved the way for further and more far reaching reforms by Atatürk's regime.

During this time tensions flared between Talaat and Enver. Enver won out in a conflict over prioritizing rationing in favor of the army. In response Talaat established the Ministry of Rationing

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian mi ...

, and appointed Kara Kemal as its head. In a play of ''zugzwang

Zugzwang (German for "compulsion to move", ) is a situation found in chess and other turn-based games wherein one player is put at a disadvantage because of their obligation to make a move; a player is said to be "in zugzwang" when any legal move ...

'' after the Balfour Declaration, Talaat reproached with the Zionist movement

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Jew ...

, promising to open up Jewish immigration to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

. This promise did not reflect ground conditions, as his first year as Grand Vizier saw the loss of Jerusalem and Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

.

However territorial loss in the south coincided with diplomatic success with the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty in March 1918, with Talaat himself negotiating for the Ottoman Empire, resulting in the return of Kars, Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the second largest city of Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's southwest. It is situated in a subtropical zone at the foot of t ...

, and Ardahan

Ardahan (, ka, არტაანი, tr, hy, Արդահան, translit=Ardahan Russian: Ардаган) is a city in northeastern Turkey, near the Georgian border.

It is the capital of Ardahan Province.

History

Ancient and medieval

Ardaha ...

to Ottoman rule after their loss forty years ago. Another treaty with the Caucasian states signed in Batum strengthened the Ottoman's position in a future drive on Baku, which was accomplished by September. Spring 1918 was the zenith of Unionist power and Talaat Pasha's political career, followed by a slow realization of defeat in WWI over the summer. In a conversation with Cavid, Talaat felt trapped between three "fires": Enver Pasha, who was becoming increasingly erratic and overly optimistic after the breakthrough in the Caucasus; the new sultan Mehmed VI, an anti-Unionist who was more assertive than his deceased half brother, and the Allied armies advancing from the West and the South. In October 1918, the British defeated both Ottoman armies they faced in the Palestinian front. Simultaneously on the Macedonian front, Bulgaria capitulated to the allies, leaving no sufficient forces to check an advance on the Ottoman capital. With defeat certain (and growing unrest from years of unfettered corruption) Talaat Pasha announced his intention to resign on 8 October 1918 and lead a caretaker government for a few more days. Ahmed İzzet Pasha became the new Grand Vizier and signed the Armistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by th ...

with the Allies, ending hostilities in the Middle East on 30 October.

Exile: 1918–1921

Escape to Germany

Talaat Pasha delivered a farewell speech in the last CUP congress on 1 November, where it was decided to dissolve the party. With Enver, Cemal, Nazım, Şakir, Azmi, and Osman Bedri, he fled the Ottoman capital on a German

Talaat Pasha delivered a farewell speech in the last CUP congress on 1 November, where it was decided to dissolve the party. With Enver, Cemal, Nazım, Şakir, Azmi, and Osman Bedri, he fled the Ottoman capital on a German torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

that night where they landed in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, Crimea and scattered from there. Before escaping the Ottoman Empire, he wrote a letter to İzzet Pasha promising his return to the country. Public opinion was shocked by the departure of Talaat Pasha, even though he had been known to turn a blind eye on corrupt ministers appointed because of their associations with the CUP.

Talaat, Nazım, and Şakir wound up in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

on 10 November, the day after Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

fled the city due to the November Revolution. The new chancellor, Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (; 4 February 187128 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on t ...

of the SPD

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been t ...

, signed the documents secretly allowing Talaat asylum in Germany, where he and Nazım settled in a flat at Hardenbergerstraße 4 ( Ernst-Reuter Square), Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Prussia, it is best known for Charlottenburg Palace, the ...

, under the pseudonym "Ali Sâî Bey". Next to his apartment he founded the "Oriental Club" (Şark Kulübesi), where anti-Entente Muslims and European activists met. Though he was a wanted man in the Ottoman Empire and Britain, Talaat managed to attend the Socialist International

The Socialist International (SI) is a political international or worldwide organisation of political parties which seek to establish democratic socialism. It consists mostly of socialist and labour-oriented political parties and organisations ...

in the Netherlands. He was also able to travel to Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, and Denmark. In all of these visits, he lobbied against the new Allied world-order, specifically against their designs on the Ottoman Empire. Behind bars for his role in the Sparticist uprising, Karl Radek reconnected Talaat (their previous encounter being on opposite sides of the negotiating table at Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

) who frequently visited him at Moabit prison. Despite his mobility, his exile was one of practical poverty. At one point wishing to start a newspaper, he didn't have enough money to do so, so he wrote his memoirs instead.

Questioned whether he would return and join the Turkish nationalist movement, Talaat declined, arguing that Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk) is now the new leader. He held regular correspondences with Mustafa Kemal from Berlin. Unlike Enver, Kemal had friendly relations with Talaat, with Kemal addressing Talaat as his "brother" in their communiques. Even though he effectively endorsing Mustafa Kemal as his "successor", from Berlin Talaat was able to directly issue orders to Turkish commanders in the opening stages of the Turkish War of Independence

The Turkish War of Independence "War of Liberation", also known figuratively as ''İstiklâl Harbi'' "Independence War" or ''Millî Mücadele'' "National Struggle" (19 May 1919 – 24 July 1923) was a series of military campaigns waged by th ...

. He also kept in contact with Tevfik Rüştü (Aras), Halide Edip (Adıvar), Celal (Bayar), Abdülkadir Cami (Baykut) and Nuri (Conker). The Ankara government

The Government of the Grand National Assembly ( tr, Büyük Millet Meclisi Hükûmeti), self-identified as the State of Turkey () or Turkey (), commonly known as the Ankara Government (),Kemal Kirişci, Gareth M. Winrow: ''The Kurdish Question and ...

sent the ambassadors Bekir Sami (Kunduh) and Galip Kemali (Söylemezoğlu) to meet with Talaat and support his network that assisted the Turkish nationalist movement from abroad. Through these efforts, he was able to cobble together a disparate coalition of Turkish nationalists, German nationalists, and Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

.

After the failure of the Kapp Putsch

The Kapp Putsch (), also known as the Kapp–Lüttwitz Putsch (), was an attempted coup against the German national government in Berlin on 13 March 1920. Named after its leaders Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz, its goal was to undo th ...

Talaat offered comments in the subsequent press conference, criticizing the putschists for their dilettantism, exclaiming "A putsch without a cabinet ready at hand was just childish."

Trial and conviction

The British government exerted diplomatic pressure on the

The British government exerted diplomatic pressure on the Ottoman Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

and brought to trial the Ottoman leaders who had held positions of responsibility between 1914 and 1918 for having perpetrated the Armenian genocide. İzzet Pasha was pressured early on by the British to arrest Talaat, but he didn't order his arrest nor order his extradition from Germany until a Constantinople court demanded it. With the allied occupation of Constantinople

The occupation of Istanbul ( tr, İstanbul'un İşgali; 12 November 1918 – 4 October 1923), the capital of the Ottoman Empire, by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces, took place in accordance with the Armistice of Mudros, which ended Ot ...

, İzzet Pasha resigned. Ahmet Tevfik Pasha took the position of grand vizier the same day that Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

ships entered the Golden Horn. Talaat's remaining property was confiscated during Tevfik Pasha's premiership, which lasted until 4 March 1919. He was replaced by Damat Ferid Pasha

Damat Mehmed Adil Ferid Pasha ( ota, محمد عادل فريد پاشا tr, Damat Ferit Paşa; 1853 – 6 October 1923), known simply as Damat Ferid Pasha, was an Ottoman liberal statesman, who held the office of Grand Vizier, the ' ...

, whose first order was the arrest of leading members of Union and Progress. Those who were caught were put under arrest at the Bekirağa division and were subsequently exiled to Malta. Courts-martials were then organized to punish the CUP for the empire's ill-conceived involvement in World War I.

By January 1919, a report to Sultan Mehmed VI accused over 130 suspects, most of whom were high officials. The indictment accused the main defendants, including Talaat, of being "mired in an unending chain of bloodthirstiness, plunder and abuses". They were accused of deliberately engineering Turkey's entry into the war "by a recourse to a number of vile tricks and deceitful means". They were also accused of "the massacre and destruction of the Armenians" and of trying to "pile up fortunes for themselves" through "the pillage and plunder" of their possessions. The indictment alleged that "The massacre and destruction of the Armenians were the result of decisions by the Central Committee of Ittihadd". The court released its verdict on 5 July 1919: Talaat's title of Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignitar ...

was stripped, and he, Enver, Cemal, Nazım, and Şakir were condemned to death in absentia.

Monitoring by British intelligence

The British government continued to monitor Talaat's activities after the war. The British government had intelligence reports indicating that he had gone to Germany, and the British High Commissioner pressured Ferid Pasha and the Sublime Porte to request that Germany extradite him to the Ottoman Empire. Germany was well aware of Talaat's presence but refused to surrender him. The last official interview Talaat granted was toAubrey Herbert

Colonel The Honourable Aubrey Nigel Henry Molyneux Herbert (3 April 1880 – 26 September 1923), of Pixton Park in Somerset and of Teversal, in Nottinghamshire, was a British soldier, diplomat, traveller, and intelligence officer associat ...

, a British intelligence agent. During this interview, Talaat maintained at several points that the CUP had always sought British friendship and advice, but claimed that Britain had never replied to such overtures in any meaningful way.

Assassination and funeral

With most CUP leaders in exile, the

With most CUP leaders in exile, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

organized a plot to assassinate the perpetrators of the Armenian Genocide, known as Operation Nemesis

Operation Nemesis () was a program to assassinate both Ottoman perpetrators of the Armenian genocide and officials of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic responsible for the massacre of Armenians during the September Days of 1918 in Baku. Maste ...

. On 15 March 1921 Talaat was assassinated with a single bullet as he came out of his Hardenbergstraße flat to purchase a pair of gloves. His assassin was a Dashnak

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

member from Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses the double-headed eagle as ...

named Soghomon Tehlirian, whose entire family was killed during the genocide.Operationnemesis.com/ref> Tehlirian admitted to the shooting, but, after a cursory two-day trial, he was found innocent by a German court on grounds of

temporary insanity

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the ...