Megabyzus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Megabyzus ( grc, Μεγάβυζος, a folk-etymological alteration of

After this Megabyzus became satrap of

After this Megabyzus became satrap of

I, 110

/ref> and of this time the final 18 months was occupied with the siege of Prosoptis.Thucydide

I, 109

/ref> According to Thucydides, at first Artaxerxes sent Megabazus to try and bribe the Spartans into invading

VIII, 126

/ref> It is clearly possible that the Persian forces did spend some prolonged time in training, since it took four years for them to respond to the Egyptian victory at Papremis. Although neither author gives many details, it is clear that when Megabyzus finally arrived in Egypt, he was able to quickly lift the siege of Memphis, defeating the Egyptians in battle, and driving the Athenians from Memphis.Diodoru

XI, 77

/ref>

Jona Lendering - Megabyzus

Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native speakers as ( ...

Bagabuxša, meaning "God saved") was an Achaemenid Persian general, son of Zopyrus

Zopyrus (; el, Ζώπυρος) (fl. 522 BC-500 BC) was a Persian nobleman mentioned in Herodotus' '' Histories''.

He was son of Megabyzus I, who helped Darius I in his ascension. According to Herodotus, when Babylon revolted against the ru ...

, satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

of Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c ...

, and grandson of Megabyzus I {{Short description, Key families during Persian Achaemenid era

Seven Achaemenid clans or seven Achaemenid houses were seven significant families that had key roles during the Achaemenid era. Only one of them had regnant pedigree.

Nobles of the s ...

, one of the seven conspirators who had put Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

on the throne. His father was killed when the satrapy rebelled in 484 BCE, and Megabyzus led the forces that recaptured the city, after which the statue of the god Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

was destroyed to prevent future revolts. Megabyzus subsequently took part in the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasio ...

(480-479 BCE). Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

claims that he refused to act on orders to pillage Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

, but it is doubtful such orders were ever given.

Revolt

According toCtesias

Ctesias (; grc-gre, Κτησίας; fl. fifth century BC), also known as Ctesias of Cnidus, was a Greek physician and historian from the town of Cnidus in Caria, then part of the Achaemenid Empire.

Historical events

Ctesias, who lived in the fi ...

, who is not especially reliable but is often our only source, Amytis, wife of Megabyzus and daughter of Xerxes, was accused of adultery shortly afterwards. As such, Megabyzus took part in the conspiracy of Artabanus to assassinate the emperor, but betrayed him before he could kill the new emperor Artaxerxes as well. In a battle, Artabanus' sons were killed and Megabyzus was wounded, but Amytis interceded on his behalf and he was cured.

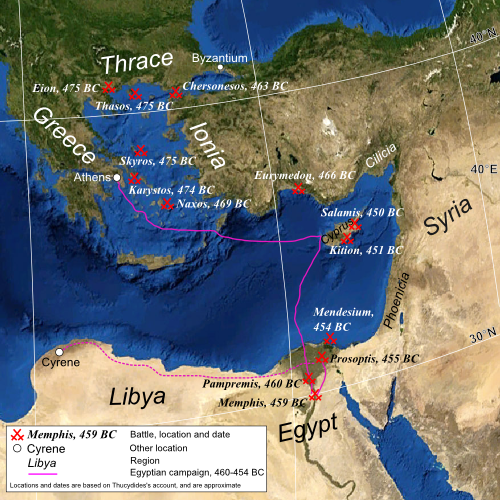

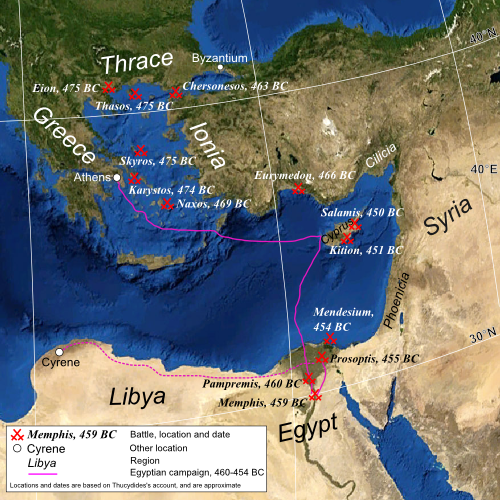

Egyptian campaign

After this Megabyzus became satrap of

After this Megabyzus became satrap of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. Together with Artabazus, satrap of Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empir ...

, he had command of the Persian armies sent to put down the revolt of Inarus

Inaros (II), also known as Inarus, (fl. ca. 460 BC) was an Egyptian rebel ruler who was the son of an Egyptian prince named Psamtik, presumably of the old Saite line, and grandson of Psamtik III. In 460 BC, he revolted against the Persians wit ...

in Egypt. They arrived in 456 BC, and within two years had put down the revolt, capturing Inarus and various Athenians supporting him.

Origin of the Egyptian campaign

WhenXerxes I

Xerxes I ( peo, 𐎧𐏁𐎹𐎠𐎼𐏁𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ξέρξης ; – August 465 BC), commonly known as Xerxes the Great, was the fourth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, ruling from 486 to 465 BC. He was the son and successor of D ...

was assassinated in 465 BCE, he was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes I

Artaxerxes I (, peo, 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎠 ; grc-gre, Ἀρταξέρξης) was the fifth King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, from 465 to December 424 BC. He was the third son of Xerxes I.

He may have been the " Artas ...

, but several parts of the Achaemenid empire soon revolted, foremost of which were Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, sou ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. The Egyptian Inarus

Inaros (II), also known as Inarus, (fl. ca. 460 BC) was an Egyptian rebel ruler who was the son of an Egyptian prince named Psamtik, presumably of the old Saite line, and grandson of Psamtik III. In 460 BC, he revolted against the Persians wit ...

defeated the Persian satrap of Egypt Achaemenes

Achaemenes ( peo, 𐏃𐎧𐎠𐎶𐎴𐎡𐏁 ; grc, Ἀχαιμένης ; la, Achaemenes) was the apical ancestor of the Achaemenid dynasty of rulers of Persia.

Other than his role as an apical ancestor, nothing is known of his life or a ...

, a brother of Artaxerxes, and took control of Lower Egypt. He contacted the Greeks, who were also officially still at war with Persia, and in 460 BCE, Athens sent an expeditionary force of 200 ships and 6000 heavy infantry to support Inarus. The Egyptian and Athenian troops defeated the local Persian troops of Egypt, and captured the city of Memphis, except for the Persian citadel which they besieged for several years.

Siege of Memphis (459–455 BCE)

The Athenians and Egyptians had settled down to besiege the local Persian troops in Egypt, at the White Castle. The siege evidently did not progress well, and probably lasted for at least four years, since Thucydides says that their whole expedition lasted 6 years,ThucydideI, 110

/ref> and of this time the final 18 months was occupied with the siege of Prosoptis.Thucydide

I, 109

/ref> According to Thucydides, at first Artaxerxes sent Megabazus to try and bribe the Spartans into invading

Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean ...

, to draw off the Athenian forces from Egypt. When this failed, he instead assembled a large army under Megabyzus, and dispatched it to Egypt. Diodorus has more or less the same story, with more detail; after the attempt at bribery failed, Artaxerxes put Megabyzus and Artabazus in charge of 300,000 men, with instructions to quell the revolt. They went first from Persia to Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

and gathered a fleet of 300 triremes from the Cilicians, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns and Cypriots, and spent a year training their men. Then they finally headed to Egypt. Modern estimates, however, place the number of Persian troops at the considerably lower figure of 25,000 men given that it would have been highly impractical to deprive the already strained satrapies of any more man power than that. Thucydides does not mention Artabazus, who is reported by Herodotus to have taken part in the second Persian invasion; Diodorus may be mistaken about his presence in this campaign.HerodotuVIII, 126

/ref> It is clearly possible that the Persian forces did spend some prolonged time in training, since it took four years for them to respond to the Egyptian victory at Papremis. Although neither author gives many details, it is clear that when Megabyzus finally arrived in Egypt, he was able to quickly lift the siege of Memphis, defeating the Egyptians in battle, and driving the Athenians from Memphis.Diodoru

XI, 77

/ref>

Siege of Prosopitis (455 BCE)

The Athenians now fell back to the island of Prosopitis in the Nile delta, where their ships were moored. There, Megabyzus laid siege to them for 18 months, until finally he was able to drain the river from around the island by digging canals, thus "joining the island to the mainland". In Thucydides's account the Persians then crossed over to the former island, and captured it. Only a few of the Athenian force, marching through Libya to Cyrene survived to return to Athens. In Diodorus's version, however, the draining of the river prompted the Egyptians (whom Thucydides does not mention) to defect and surrender to the Persians. The Persians, not wanting to sustain heavy casualties in attacking the Athenians, instead allowed them to depart freely to Cyrene, whence they returned to Athens. Since the defeat of the Egyptian expedition caused a genuine panic in Athens, including the relocation of the Delian treasury to Athens, Thucydides's version is probably more likely to be correct.Holland, p. 363.Cyprus campaign

They then turned their attention toCyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, which was under attack by the Athenians, led by Cimon

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, Κίμων; – 450BC) was an Athenian ''strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Batt ...

. Shortly afterwards hostilities between Persia and Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

ceased, called the peace of Callias.

Revolt

Some time later Megabyzus himself revolted. Ctesias tells us the reason was thatAmestris

Amestris ( el, Άμηστρις, ''Amēstris'', perhaps the same as Άμαστρις, ''Amāstris'', from Old Persian ''Amāstrī-'', "strong woman"; died c. 424 BC) was a Persian queen, the wife of Xerxes I of Persia, mother of Achaemenid King ...

had the captives from the Egyptian revolt executed, though Megabyzus had given his word that they would not be harmed.

Armies under Usiris of Egypt and then prince Menostanes, a nephew of the king, were sent against him, both foregoing battle for (non-fatal) duels between the generals, and in both cases Megabyzus was victorious. The king resolved to send his brother Artarius, the eunuch Artoxares and Amytis in a peace embassy. His honour restored, Megabyzus agreed to surrender and was pardoned, retaining his position. Some time later, Megabyzus saved Artaxerxes from a lion in a hunt and was subsequently exiled to Cyrtae for violating the royal prerogative to make the first kill, but he returned to Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo- Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

by pretending to be a leper

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria '' Mycobacterium leprae'' or '' Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve d ...

and was pardoned.

Megabyzus died shortly afterwards, at age 76. His son Zopyrus II

Zopyrus (; el, Ζώπυρος) (fl. 522 BC-500 BC) was a Persian nobleman mentioned in Herodotus' '' Histories''.

He was son of Megabyzus I, who helped Darius I in his ascension. According to Herodotus, when Babylon revolted against the ru ...

is known to have lived as an exile in Athens, and aided in its assault on Caunus during his father's exile, where he was killed by a rock.

References

External links

Jona Lendering - Megabyzus

See also

* Megabazus * Megabates {{Achaemenid rulers 5th-century BC deaths Persian people of the Greco-Persian Wars Military leaders of the Achaemenid Empire Year of birth unknown 5th-century BC Iranian people