Mary Seacole on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mary Jane Seacole (;Anionwu E.N. (2012) Mary Seacole: nursing care in many lands. ''British Journal of Healthcare Assistants'' 6(5), 244–248. 23 November 1805 – 14 May 1881) was a British-Jamaican nurse and businesswoman who set up the "British Hotel" behind the lines during the

Statue of 'nurse' Mary Seacole will do Florence Nightingale a disservice

' (2012)The Nightingale Society - /nightingalesociety.com/correspondence/statue/ Correspondence on the Seacole Statue/ref>

National Library of Jamaica. Retrieved 4 April 2019. In the 18th century, Jamaican doctresses mastered folk medicine, including the use of hygiene and herbs. They had a vast knowledge of tropical diseases, and had a general practitioner's skill in treating ailments and injuries, acquired from having to look after the illnesses of fellow slaves on sugar plantations.Robinson, p. 10. At Blundell Hall, Seacole acquired her nursing skills, which included the use of hygiene, ventilation, warmth, hydration, rest, empathy, good nutrition and care for the dying. Blundell Hall also served as a convalescent home for military and naval staff recuperating from illnesses such as cholera and yellow fever. Seacole's autobiography says she began experimenting in medicine, based on what she learned from her mother, by ministering to a doll and then progressing to pets before helping her mother treat humans. Because of her family's close ties with the army, she was able to observe the practices of military doctors, and combined that knowledge with the West African remedies she acquired from her mother. In Jamaica in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, neonatal deaths were more than a quarter of total births. However, Seacole, using traditional West African herbal remedies and hygienic practices, boasted that she never lost a mother or her child. Seacole was proud of both her Jamaican and Scottish ancestry and called herself a Creole In her autobiography, ''The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole'', she writes: "I am a Creole, and have good Scots blood coursing through my veins. My father was a soldier of an old Scottish family." Robinson speculates that she may technically have been a

The epidemic raged through the population. Seacole later expressed exasperation at their feeble resistance, claiming they "bowed down before the plague in slavish despair". She performed an

The epidemic raged through the population. Seacole later expressed exasperation at their feeble resistance, claiming they "bowed down before the plague in slavish despair". She performed an

The Crimean War lasted from October 1853 until 1 April 1856 and was fought between the

The Crimean War lasted from October 1853 until 1 April 1856 and was fought between the  Seacole often went out to the troops as a sutler, selling her provisions near the British camp at Kadikoi, and nursing casualties brought out from the trenches around Sevastopol or from the Tchernaya valley. She was widely known to the British Army as "Mother Seacole".

Apart from serving officers at the British Hotel, Seacole also provided catering for spectators at the battles, and spent time on Cathcart's Hill, some north of the British Hotel, as an observer. On one occasion, attending wounded troops under fire, she dislocated her right thumb, an injury which never healed entirely.Seacole, Chapter XVI. In a dispatch written on 14 September 1855,

Seacole often went out to the troops as a sutler, selling her provisions near the British camp at Kadikoi, and nursing casualties brought out from the trenches around Sevastopol or from the Tchernaya valley. She was widely known to the British Army as "Mother Seacole".

Apart from serving officers at the British Hotel, Seacole also provided catering for spectators at the battles, and spent time on Cathcart's Hill, some north of the British Hotel, as an observer. On one occasion, attending wounded troops under fire, she dislocated her right thumb, an injury which never healed entirely.Seacole, Chapter XVI. In a dispatch written on 14 September 1855,

After the end of the war, Seacole returned to England destitute and in poor health. In the conclusion to her autobiography, she records that she "took the opportunity" to visit "yet other lands" on her return journey, although Robinson attributes this to her impecunious state requiring a roundabout trip. She arrived in August 1856 and opened a canteen with Day at

After the end of the war, Seacole returned to England destitute and in poor health. In the conclusion to her autobiography, she records that she "took the opportunity" to visit "yet other lands" on her return journey, although Robinson attributes this to her impecunious state requiring a roundabout trip. She arrived in August 1856 and opened a canteen with Day at  In researching his biography of

In researching his biography of

Seacole joined the

Seacole joined the

While well known at the end of her life, Seacole rapidly faded from public memory in Britain. She was cited as an example of "hidden" black history in

While well known at the end of her life, Seacole rapidly faded from public memory in Britain. She was cited as an example of "hidden" black history in  British buildings and organisations now commemorate her by name. One of the first was the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at Thames Valley University, which created the NHS Specialist Library for Ethnicity and Health, a web-based collection of research-based evidence and good practice information relating to the health needs of minority ethnic groups, and other resources relevant to multi-cultural health care. There is another Mary Seacole Research Centre, this one at

British buildings and organisations now commemorate her by name. One of the first was the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at Thames Valley University, which created the NHS Specialist Library for Ethnicity and Health, a web-based collection of research-based evidence and good practice information relating to the health needs of minority ethnic groups, and other resources relevant to multi-cultural health care. There is another Mary Seacole Research Centre, this one at

NHS Leadership Academy

has developed a six-month leadership course called the Mary Seacole Programme, which is designed for first time leaders in healthcare. An exhibition to celebrate the bicentenary of her birth opened at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London in March 2005. Originally scheduled to last for a few months, the exhibition was so popular that it was extended to March 2007. A campaign to erect a statue of Seacole in London was launched on 24 November 2003, chaired by

A campaign to erect a statue of Seacole in London was launched on 24 November 2003, chaired by

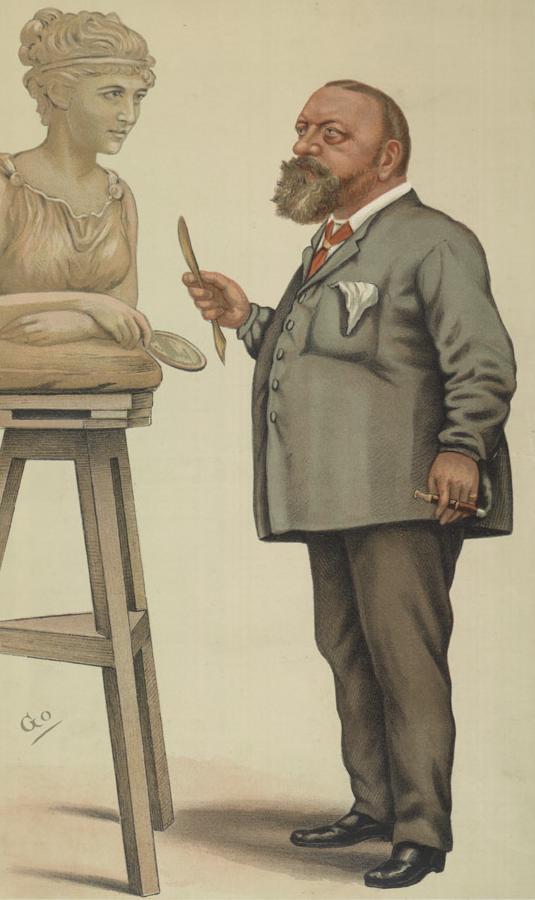

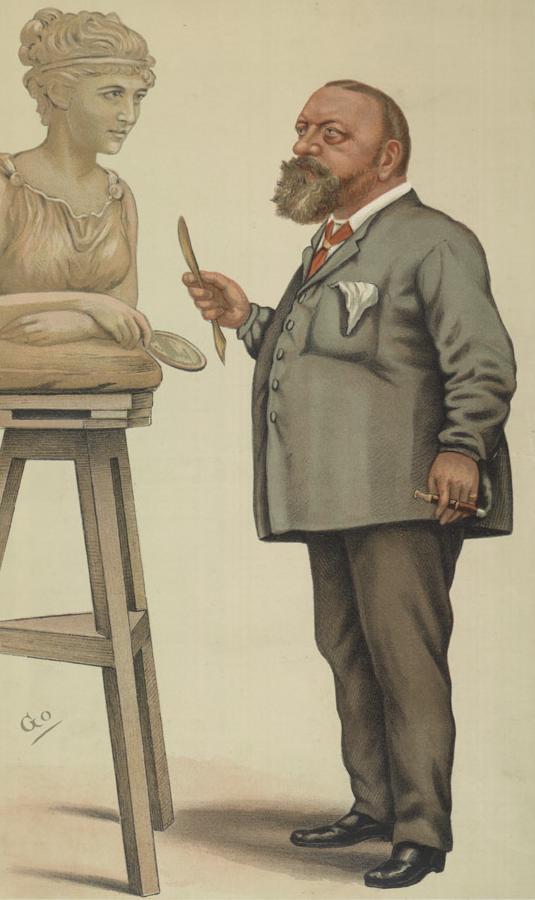

''History Today'', Volume 62, Issue 9, 2012. but it was unveiled on 30 June 2016. The words written by Russell in ''The Times'' in 1857 are etched on to Seacole's statue: "I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them, and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead."Kashmira Gander

''The Independent'', 24 June 2016. The making of the Jennings statue was recorded in the ITV documentary ''

"Rubbishing Mary Seacole is another move to hide the contributions of black people"

''The Guardian'', 21 June 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2019. An article by Lynn McDonald in ''The Times Literary Supplement'' asked "How did Mary Seacole come to be viewed as a pioneer of modern nursing?", comparing her unfavourably with Kofoworola Pratt who was the first black nurse in the NHS, and concluded "She deserves much credit for rising to the occasion, but her tea and lemonade did not save lives, pioneer nursing or advance health care". Jennings has suggested that Seacole's race has played a part in the resistance by some of Nightingale's supporters. The American academic Gretchen Gerzina has also affirmed this theory, claiming that many of the supposed criticisms leveled at Seacole are due to her race. One criticism of Seacole made by supporters of Nightingale is that she was not trained at an accredited medical institution. However, Jamaican women such as 18th century practitioners

''Huffington Post'', 7 January 2013. Susan Sheridan has argued that the leaked proposal to remove Seacole from the National Curriculum is part of "a concentration solely on large-scale political and military history and a fundamental shift away from social history." Many commentators do not accept the view that Seacole's accomplishments were exaggerated. British social commentator has opined that many of the claims that Seacole's achievements were exaggerated have come from an establishment that is determined to suppress and hide the black contribution to British history. Helen Seaton claims that Nightingale fitted the Victorian ideal of a heroine more than Seacole, and that Seacole managing to overcome

"Ministering on distant shores"

''The Guardian'', 14 February 2004. * ontains a photograph* Jay Margrave: ''Can her Glory ever Fade?: A Life of Mary Seacole'', Goldenford Publishers Ltd, 2016 () * Sandra Pouchet Paquet. "The Enigma of Arrival: The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands," ''African American Review'' (1992) 26#4 pp. 651–66

in JSTOR

* Helen Rappaport, ''No Place for Ladies: The Untold Story of Women in the Crimean War'', Arum, 2007. * Helen Rappaport, ''In Search of Mary Seacole: The making of a cultural icon'', Simon and Schuster, 2022. * Ziggi Alexander & Audrey Dewjee, ''Mary Seacole: Jamaican National Heroine and Doctress in the Crimean War'', Brent Library Service, 1982 ( pb) * Ziggi Alexander, "Let it Lie Upon the Table: The Status of Black Women's Biography in the UK", ''Gender & History'', Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring 1990, pp. 22–33 (ISSN 0953-5233) * Lynn McDonald, “Wonderful Adventures--How did Mary Seacole come to be viewed as a Pioneer of Modern Nursing?” Times Literary Supplement (6 December 2013):14-15. * Lynn McDonald, “Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole: Which is the Forgotten Hero of Health Care and Why.” Scottish Medical Journal 59,1 (1 February 2014):66-69; “Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole on Nursing and Health Care.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 69,11 (November 2013).

"History – Historic Figures: Mary Seacole (1805 – 1881)"

BBC, 2014. *"Mary Seacole Fundraising Ball." ''The Bristol Mercury'', 1857. *National Geographic Society. /www.nationalgeographic.org/news/mary-seacole/ "Mary Seacole."''National Geographic Society'', National Geographic, 15 October 2012. *Seacole, Mary. /digital.library.upenn.edu/women/seacole/adventures/adventures.html#I "ADVENTURES OF MRS. SEACOLE." ''The Story of My Life.'' Philadelphia: Jas. B. Rodgers Printing Co. {{DEFAULTSORT:Seacole, Mary 1805 births 1881 deaths English people of Jamaican descent English people of Scottish descent Jamaican people of Scottish descent British people of the Crimean War Jamaican nurses Women nurses Women of the Victorian era English women writers Jamaican women writers Jamaican autobiographers Black British women writers Black British people in health professions People from Kingston, Jamaica Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica) Converts to Roman Catholicism Burials at St Mary's Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green Women autobiographers 19th-century English women writers 19th-century Jamaican people Black British history 19th-century British businesswomen Free people of color

Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

.Bonnie McKay Harmer, ''Silenced in history: A historical study of Mary Seacole'' (2010). She described the hotel as "a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers", and provided succour for wounded service men on the battlefield, nursing many of them back to health. Coming from a tradition of Jamaican and West African " doctresses", Seacole displayed "compassion, skills and bravery while nursing soldiers during the Crimean War", through the use of herbal remedies. She was posthumously awarded the Jamaican Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

in 1991. In 2004, she was voted the greatest black Briton in a survey conducted in 2003 by the black heritage website Every Generation.

It has been argued that Seacole was the first British nurse practitioner

A nurse practitioner (NP) is an advanced practice registered nurse and a type of mid-level practitioner. NPs are trained to assess patient needs, order and interpret diagnostic and laboratory tests, diagnose disease, formulate and prescribe ...

(in the sense of a practising nurse with advanced medical skills). Hoping to assist with nursing the wounded on the outbreak of the Crimean War, Seacole applied to the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

to be included among the nursing contingent but was refused, so she travelled independently and set up her hotel and tended to the battlefield wounded. She became popular among service personnel, who raised money for her when she faced destitution after the war. In 1857 a four-day fundraising gala took place in London to honour Seacole. About 40,000 attended, including veterans.

She was largely forgotten for almost a century after her death. Her autobiography, ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'' (1857), was the first autobiography written by a black woman in Britain, although some aspects of its accuracy have been questioned. The erection of a statue of her at St Thomas' Hospital, London, on 30 June 2016, describing her as a "pioneer", generated some controversy and opposition, especially among those concerned with Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War ...

's legacy.The Guardian Opinion - Lynn McDonald Statue of 'nurse' Mary Seacole will do Florence Nightingale a disservice

' (2012)The Nightingale Society - /nightingalesociety.com/correspondence/statue/ Correspondence on the Seacole Statue/ref>

Early career and background

Mary Jane Seacole was born Mary Jane Grant on November 23, 1805 in Kingston, in theColony of Jamaica

The Crown Colony of Jamaica and Dependencies was a British colony from 1655, when it was captured by the English Protectorate from the Spanish Empire. Jamaica became a British colony from 1707 and a Crown colony in 1866. The Colony was prima ...

as a member of the community of free black people in Jamaica

Free black people in Jamaica fell into two categories. Some secured their freedom officially, and lived within the slave communities of the Colony of Jamaica. Others ran away from slavery, and formed independent communities in the forested mountai ...

. She was the daughter of James Grant, a Scottish''Scotland on Sunday'', 16 May 2010, p. 10. Lieutenant in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

.Seacole, Chapter 1. Her mother, Mrs Grant, nicknamed "The Doctress", was a healer who used traditional Caribbean and African herbal medicines. Mrs Grant also ran Blundell Hall, a boarding house at 7, East Street."Mary Seacole (1805-1881)"National Library of Jamaica. Retrieved 4 April 2019. In the 18th century, Jamaican doctresses mastered folk medicine, including the use of hygiene and herbs. They had a vast knowledge of tropical diseases, and had a general practitioner's skill in treating ailments and injuries, acquired from having to look after the illnesses of fellow slaves on sugar plantations.Robinson, p. 10. At Blundell Hall, Seacole acquired her nursing skills, which included the use of hygiene, ventilation, warmth, hydration, rest, empathy, good nutrition and care for the dying. Blundell Hall also served as a convalescent home for military and naval staff recuperating from illnesses such as cholera and yellow fever. Seacole's autobiography says she began experimenting in medicine, based on what she learned from her mother, by ministering to a doll and then progressing to pets before helping her mother treat humans. Because of her family's close ties with the army, she was able to observe the practices of military doctors, and combined that knowledge with the West African remedies she acquired from her mother. In Jamaica in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, neonatal deaths were more than a quarter of total births. However, Seacole, using traditional West African herbal remedies and hygienic practices, boasted that she never lost a mother or her child. Seacole was proud of both her Jamaican and Scottish ancestry and called herself a Creole In her autobiography, ''The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole'', she writes: "I am a Creole, and have good Scots blood coursing through my veins. My father was a soldier of an old Scottish family." Robinson speculates that she may technically have been a

quadroon

In the colonial societies of the Americas and Australia, a quadroon or quarteron was a person with one quarter African/ Aboriginal and three quarters European ancestry.

Similar classifications were octoroon for one-eighth black (Latin root ''oc ...

. Seacole emphasises her personal vigour in her autobiography, distancing herself from the contemporary stereotype of the "lazy Creole", She was proud of her black ancestry, writing, "I have a few shades of deeper brown upon my skin which shows me related – and I am proud of the relationship – to those poor mortals whom you once held enslaved, and whose bodies America still owns."Seacole, Chapter II.

Mary Seacole spent some years in the household of an elderly woman, whom she called her "kind patroness", before returning to her mother. She was treated as a member of her patroness's family and received a good education. As the educated daughter of a Scottish officer and a free black woman with a respectable business, Seacole would have held a high position in Jamaican society.

In about 1821, Seacole visited London, staying for a year, and visited her relatives in the merchant Henriques family. Although London had a number of black people, she records that a companion, a West Indian with skin darker than her own "dusky" shades, was taunted by children. Seacole herself was "only a little brown"; she was nearly white according to one of her biographers, Dr. Ron Ramdin. She returned to London approximately a year later, bringing a "large stock of West Indian pickles and preserves for sale". Her later travels would be without a chaperone or sponsor – an unusually independent practice at a time when women had limited rights.

In the Caribbean, 1826–51

After returning to Jamaica, Seacole cared for her "old indulgent patroness" through an illness, finally returning to the family home at Blundell Hall after the death of her patroness (a woman who gave financial support to her) a few years later. Seacole then worked alongside her mother, occasionally being called to provide nursing assistance at the British Army hospital atUp-Park Camp

Up-Park Camp (often Up Park Camp) was the headquarters of the British Army in Jamaica from the late 18th century to independence in 1962. From that date, it has been the headquarters of the Jamaica Defence Force. It is located in the heart ...

. She also travelled the Caribbean, visiting the British colony of New Providence

New Providence is the most populous island in the Bahamas, containing more than 70% of the total population. It is the location of the national capital city of Nassau, whose boundaries are coincident with the island; it had a population of 246 ...

in The Bahamas, the Spanish colony of Cuba

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Cana ...

, and the new Republic of Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and so ...

. Seacole records these travels, but omits mention of significant current events, such as the Christmas Rebellion in Jamaica of 1831, the abolition of slavery in 1833, and the abolition of "apprenticeship" in 1838.

She married Edwin Horatio Hamilton Seacole in Kingston on 10 November 1836. Her marriage, from betrothal to widowhood, is described in just nine lines at the conclusion of the first chapter of her autobiography. Robinson reports the legend in the Seacole family that Edwin was an illegitimate son of Lord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought a ...

and his mistress, Emma Hamilton, who was adopted by Thomas, a local "surgeon, apothecary and man midwife" (Seacole's will indicates that Horatio Seacole was Nelson's godson: she left a diamond ring to her friend, Lord Rokeby, "given to my late husband by his godfather Viscount Nelson", but there was no mention of this godson in Nelson's own will or its codicils.) Edwin was a merchant and seems to have had a poor constitution. The newly married couple moved to Black River and opened a provisions store which failed to prosper. They returned to Blundell Hall in the early 1840s.

During 1843 and 1844, Seacole suffered a series of personal disasters. She and her family lost much of the boarding house in a fire in Kingston on 29 August 1843. Blundell Hall burned down, and was replaced by New Blundell Hall, which was described as "better than before". Then her husband died in October 1844, followed by her mother. After a period of grief, in which Seacole says she did not stir for days, she composed herself, "turned a bold front to fortune", and assumed the management of her mother's hotel. She put her rapid recovery down to her hot Creole blood, blunting the "sharp edge of ergrief" sooner than Europeans who she thought "nurse their woe secretly in their hearts".

Seacole absorbed herself in work, declining many offers of marriage. She later became known to the European military visitors to Jamaica who often stayed at Blundell Hall. She treated and nursed patients in the cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

epidemic of 1850, which killed some 32,000 Jamaicans.

In Central America, 1851–54

In 1850, Seacole'shalf-brother

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the subject. A male sibling is a brother and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised separa ...

Edward moved to Cruces, Panama, which was then part of the Republic of New Granada

The Republic of New Granada was a 1831–1858 centralist unitary republic consisting primarily of present-day Colombia and Panama with smaller portions of today's Costa Rica, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru and Brazil. On 9 May 1834, the national flag wa ...

. There, approximately up the Chagres River from the coast, he followed the family trade by establishing the Independent Hotel to accommodate the many travellers between the eastern and western coasts of the United States (the number of travellers had increased enormously, as part of the 1849 California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California f ...

). Cruces was the limit of navigability of the Chagres River during the rainy season, which lasts from June to December.Robinson, p. 61. Travellers would ride on donkeys approximately along the Las Cruces trail from Panama City

Panama City ( es, Ciudad de Panamá, links=no; ), also known as Panama (or Panamá in Spanish), is the capital and largest city of Panama. It has an urban population of 880,691, with over 1.5 million in its metropolitan area. The city is loca ...

on the Pacific Ocean coast to Cruces, and then down-river to the Atlantic Ocean at Chagres

Chagres (), once the chief Atlantic port on the isthmus of Panama, is now an abandoned village at the historical site of Fort San Lorenzo ( es, Fuerte de San Lorenzo). The fort's ruins and the village site are located about west of Colón, on ...

(or vice versa). In the dry season, the river subsided, and travellers would switch from land to the river a few miles farther downstream, at Gorgona. Most of these settlements have now been submerged by Gatun Lake, formed as part of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a condui ...

.

In 1851, Seacole travelled to Cruces to visit her brother. Shortly after her arrival, the town was struck by cholera, a disease which had reached Panama in 1849.Seacole, Chapter IV. Seacole was on hand to treat the first victim, who survived, which established Seacole's reputation and brought her a succession of patients as the infection spread. The rich paid, but she treated the poor for free. Many, both rich and poor, succumbed. She eschewed opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy '' Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which ...

, preferring mustard

Mustard may refer to:

Food and plants

* Mustard (condiment), a paste or sauce made from mustard seeds used as a condiment

* Mustard plant, one of several plants, having seeds that are used for the condiment

** Mustard seed, seeds of the mustard p ...

rubs and poultice

A poultice, also called a cataplasm, is a soft moist mass, often heated and medicated, that is spread on cloth and placed over the skin to treat an aching, inflamed, or painful part of the body. It can be used on wounds, such as cuts.

'Poultice ...

s, the laxative

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lubri ...

calomel (mercurous chloride

Mercury(I) chloride is the chemical compound with the formula Hg2Cl2. Also known as the mineral calomel (a rare mineral) or mercurous chloride, this dense white or yellowish-white, odorless solid is the principal example of a mercury(I) compound. ...

), sugars of lead (lead(II) acetate

Lead(II) acetate (Pb(CH3COO)2), also known as lead acetate, lead diacetate, plumbous acetate, sugar of lead, lead sugar, salt of Saturn, or Goulard's powder, is a white crystalline chemical compound with a slightly sweet taste. Like many other l ...

), and rehydration with water boiled with cinnamon

Cinnamon is a spice obtained from the inner bark of several tree species from the genus '' Cinnamomum''. Cinnamon is used mainly as an aromatic condiment and flavouring additive in a wide variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury dishes, breakf ...

. While her preparations had moderate success, she faced little competition, the only other treatments coming from a "timid little dentist", who was an inexperienced doctor sent by the Panamanian government, and the Roman Catholic Church.

The epidemic raged through the population. Seacole later expressed exasperation at their feeble resistance, claiming they "bowed down before the plague in slavish despair". She performed an

The epidemic raged through the population. Seacole later expressed exasperation at their feeble resistance, claiming they "bowed down before the plague in slavish despair". She performed an autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any d ...

on an orphan child for whom she had cared, which gave her "decidedly useful" new knowledge. At the end of this epidemic she herself contracted cholera, forcing her to rest for several weeks. In her autobiography, ''The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', she describes how the residents of Cruces responded: "When it became known that their "yellow doctress" had the cholera, I must do the people of Cruces the justice to say that they gave me plenty of sympathy, and would have shown their regard for me more actively, had there been any occasion."

Cholera was to return again: Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

passed through Cruces in July 1852, on military duty; a hundred and twenty men, a third of his party, died of the disease there or shortly afterwards en route to Panama City.Robinson, p. 54.

Despite the problems of disease and climate, Panama remained the favoured route between the coasts of the United States. Seeing a business opportunity, Seacole opened the British Hotel, which was a restaurant rather than a hotel. She described it as a "tumble down hut," with two rooms, the smaller one to be her bedroom, the larger one to serve up to 50 diners. She soon added the services of a barber.

As the wet season ended in early 1852, Seacole joined other traders in Cruces in packing up to move to Gorgona. She records a white American giving a speech at a leaving dinner in which he wished that "God bless the best yaller woman he ever made" and asked the listeners to join with him in rejoicing that "she's so many shades removed from being entirely black". He went on to say that "if we could bleach her by any means we would ..and thus make her acceptable in any company as she deserves to be".Seacole, Chapter VI. Seacole replied firmly that she did not "appreciate your friend's kind wishes with respect to my complexion. If it had been as dark as any nigger's, I should have been just as happy and just as useful, and as much respected by those whose respect I value." She declined the offer of "bleaching" and drank "to you and the general reformation of American manners". Salih notes Seacole's use here of eye dialect, set against her own English, as an implicit inversion of the day's caricatures of "black talk". Seacole also comments on the positions of responsibility taken on by escaped African-American slaves in Panama, as well as in the priesthood, the army, and public offices, commenting that "it is wonderful to see how freedom and equality elevate men".Seacole, Chapter V. She also records an antipathy between Panamanians and Americans, which she attributes in part to the fact that so many of the former had once been slaves of the latter.

In Gorgona, Seacole briefly ran a females-only hotel. In late 1852, she travelled home to Jamaica. Already delayed, the journey was further made difficult when she encountered racial discrimination while trying to book passage on an American ship. She was forced to wait for a later British boat. In 1853, soon after arriving home, Seacole was asked by the Jamaican medical authorities to provide nursing care to victims of a severe outbreak of yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

. She found that she could do little, because the epidemic was so severe. Her memoirs state that her own boarding house was full of sufferers and she saw many of them die. Although she wrote, "I was sent for by the medical authorities to provide nurses for the sick at Up-Park Camp

Up-Park Camp (often Up Park Camp) was the headquarters of the British Army in Jamaica from the late 18th century to independence in 1962. From that date, it has been the headquarters of the Jamaica Defence Force. It is located in the heart ...

," she did not claim to bring nurses with her when she went. She left her sister with some friends at her house, went to the camp (about a mile, or 1.6 km, from Kingston), "and did my best, but it was little we could do to mitigate the severity of the epidemic." However, in Cuba Seacole is remembered with great fondness by those she nursed back to health, where she became known as "the Yellow Woman from Jamaica with the cholera medicine".

Seacole returned to Panama in early 1854 to finalise her business affairs, and three months later moved to the New Granada Mining Gold Company establishment at Fort Bowen Mine some away near Escribanos.Seacole, Chapter VII. The superintendent, Thomas Day, was related to her late husband. Seacole had read newspaper reports of the outbreak of war against Russia before she left Jamaica, and news of the escalating Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

reached her in Panama. She determined to travel to England to volunteer as a nurse with experience in herbal healing skills, to experience the "pomp, pride and circumstance of glorious war" as she described it in Chapter I of her autobiography. A part of her reasoning for going to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

was that she knew some of the soldiers that were deployed there. In her autobiography she explains how she heard that soldiers whom she had cared for and nursed back to health in the 97th and 48th regiments were being shipped back to England in preparation for the fighting on the Crimean Peninsula.

Crimean War, 1853–56

The Crimean War lasted from October 1853 until 1 April 1856 and was fought between the

The Crimean War lasted from October 1853 until 1 April 1856 and was fought between the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

and an alliance of the United Kingdom, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

, and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

. The majority of the conflict took place on the Crimean peninsula

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and Turkey.

Many thousands of troops from all the countries involved were drafted to the area, and disease broke out almost immediately. Hundreds perished, mostly from Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium '' Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting an ...

. Hundreds more would die waiting to be shipped out, or on the voyage. Their prospects were little better when they arrived at the poorly staffed, unsanitary and overcrowded hospitals which were the only medical provision for the wounded. In Britain, a trenchant letter in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' on 14 October triggered Sidney Herbert, Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, to approach Florence Nightingale to form a detachment of nurses to be sent to the hospital to save lives. Interviews were quickly held, suitable candidates selected, and Nightingale left for Turkey on 21 October.

Seacole travelled from Navy Bay in Panama to England, initially to deal with her investments in gold-mining businesses. She then attempted to join the second contingent of nurses to the Crimea. She applied to the War Office and other government offices, but arrangements for departure were already underway. In her memoir, she wrote that she brought "ample testimony" of her experience in nursing, but the only example officially cited was that of a former medical officer of the West Granada Gold-Mining Company. However, Seacole wrote that this was just one of the testimonials she had in her possession.Seacole, Chapter VIII. Seacole wrote in her autobiography, "Now, I am not for a single instant going to blame the authorities who would not listen to the offer of a motherly yellow woman to go to the Crimea and nurse her ‘sons’ there, suffering from cholera, diarrhœa, and a host of lesser ills. In my country, where people know our use, it would have been different; but here it was natural enough – although I had references, and other voices spoke for me – that they should laugh, good-naturedly enough, at my offer."

Seacole also applied to the Crimean Fund, a fund raised by public subscription to support the wounded in Crimea, for sponsorship to travel there, but she again met with refusal. Seacole questioned whether racism was a factor in her being turned down. She wrote in her autobiography, "Was it possible that American prejudices against colour had some root here? Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?"Seacole, ''Wonderful Adventures'', Chapter VIII, pp. 73-81. An attempt to join the contingent of nurses was also rebuffed, as she wrote, "Once again I tried, and had an interview this time with one of Miss Nightingale's companions. She gave me the same reply, and I read in her face the fact, that had there been a vacancy, I should not have been chosen to fill it." Seacole did not stop after being rebuffed by the Secretary-at-War, she soon approached his wife, Elizabeth Herbert, who also informed her "that the full complement of nurses had been secured" (Seacole 78, 79).

Nightingale reportedly wrote, "I had the greatest difficulty in repelling Mrs Seacole's advances, and in preventing association between her and my nurses (absolutely out of the question!)...Anyone who employs Mrs Seacole will introduce much kindness - also much drunkenness and improper conduct".

Seacole finally resolved to travel to Crimea using her own resources and to open the British Hotel. Business card

Business cards are cards bearing business information about a company or individual. They are shared during formal introductions as a convenience and a memory aid. A business card typically includes the giver's name, company or business af ...

s were printed and sent ahead to announce her intention to open an establishment, to be called the "British Hotel", near Balaclava, which would be "a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers". Shortly afterwards, her Caribbean acquaintance, Thomas Day, arrived unexpectedly in London, and the two formed a partnership. They assembled a stock of supplies, and Seacole embarked on the Dutch screw-steamer ''Hollander'' on 27 January 1855 on its maiden voyage, to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. The ship called at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, where Seacole encountered a doctor who had recently left Scutari. He wrote her a letter of introduction to Nightingale.Seacole, Chapter IX.

Seacole visited Nightingale at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari, where she asked for a bed for the night. Seacole wrote of Selina Bracebridge

Selina Bracebridge (née Mills; 1800 – 1874) was a British artist, medical reformer, and travel writer.

Selina Bracebridge studied art under the celebrated artist Samuel Prout, and travelled widely as part of her art education.

She marri ...

, an assistant of Nightingale, "Mrs. B. questions me very kindly, but with the same look of curiosity and surprise. What object has Mrs. Seacole in coming out? This is the purport of her questions. And I say, frankly, to be of use somewhere; for other considerations I had not, until necessity forced them upon me. Willingly, had they accepted me, I would have worked for the wounded, in return for bread and water. I fancy Mrs. B— thought that I sought for employment at Scutari, for she said, very kindly – "Miss Nightingale has the entire management of our hospital staff, but I do not think that any vacancy – " Seacole informed Bracebridge that she intended to travel to Balaclava the next day to join her business partner. She reports that her meeting with Nightingale was friendly, with Nightingale asking "What do you want, Mrs. Seacole? Anything we can do for you? If it lies in my power, I shall be very happy."Seacole, Chapter IX. Seacole told her of her "dread of the night journey by caïque

A caïque ( el, καΐκι, ''kaiki'', from tr, kayık) is a traditional fishing boat usually found among the waters of the Ionian Sea, Ionian or Aegean Sea, and also a light skiff used on the Bosporus. It is traditionally a small wooden trading ...

" and the improbability of being able to find the ''Hollander'' in the dark. A bed was then found for her and breakfast sent her in the morning, with a "kind message" from Bracebridge. A footnote in the memoir states that Seacole subsequently "saw much of Miss Nightingale at Balaclava," but no further meetings are recorded in the text.

After transferring most of her stores to the transport ship ''Albatross'', with the remainder following on the ''Nonpareil'', she set out on the four-day voyage to the British bridgehead into Crimea at Balaclava.Seacole, Chapter X. Lacking proper building materials, Seacole gathered abandoned metal and wood in her spare moments, with a view to using the debris to build her hotel. She found a site for the hotel at a place she christened Spring Hill, near Kadikoi

Kadikoi ( crh, Qadıköy, russian: Кадыкой) in the 19th century was a village on the Crimean peninsula, in Ukraine, about one mile north of Balaklava. The Battle of Balaclava (also known as the Battle of Kadikoi to Russian historians) was ...

, some along the main British supply road from Balaclava to the British camp near Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, and within a mile of the British headquarters.Seacole, Chapter XI.

The hotel was built from the salvaged driftwood, packing cases, iron sheets, and salvaged architectural items such as glass doors and window-frames, from the village of Kamara, using hired local labour. The new British Hotel opened in March 1855. An early visitor was Alexis Soyer

Alexis Benoît Soyer (4 February 18105 August 1858) was a French chef who became the most celebrated cook in Victorian England. He also tried to alleviate suffering of the Irish poor in the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), and contributed a p ...

, a noted French chef who had travelled to Crimea to help improve the diet of British soldiers. He records meeting Seacole in his 1857 work ''A Culinary Campaign'' and describes Seacole as "an old dame of a jovial appearance, but a few shades darker than the white lily". Seacole requested Soyer's advice on how to manage her business, and was advised to concentrate on food and beverage service, and not to have beds for visitors because the few either slept on board ships in the harbour or in tents in the camp.Alexis Soyer, ''Soyer's Culinary Campaign'',(London: G. Routledge, 1857), p. 233.

The hotel was completed in July at a total cost of £800. It included a building made of iron, containing a main room with counters and shelves and storage above, an attached kitchen, two wooden sleeping huts, outhouses, and an enclosed stable-yard.Seacole, Chapter XII. The building was stocked with provisions shipped from London and Constantinople, as well as local purchases from the British camp near Kadikoi and the French camp at nearby Kamiesch

Kamiesch is a sea inlet and adjoining port, sited on the Chersonese or Khersones peninsula, three miles SW of the city centre of Sevastopol and ten miles WNW of Balaklava in the Crimean peninsula. During the Crimean war, French invading forces us ...

. Seacole sold anything – "from a needle to an anchor"—to army officers and visiting sightseers. Meals were served at the Hotel, cooked by two black cooks, and the kitchen also provided outside catering.

Despite constant thefts, particularly of livestock, Seacole's establishment prospered. Chapter XIV of ''Wonderful Adventures'' describes the meals and supplies provided to officers. They were closed at 8 pm daily and on Sundays. Seacole did some of the cooking herself: "Whenever I had a few leisure moments, I used to wash my hands, roll up my sleeves, and roll out pastry." When called to "dispense medications," she did so.Seacole, Chapter XIV. Soyer was a frequent visitor, and praised Seacole's offerings,Seacole, Chapter XV. noting that she offered him champagne on his first visit.

To Soyer, near the time of departure, Florence Nightingale acknowledged favourable views of Seacole, consistent with their one known meeting in Scutari. Soyer's remarks—he knew both women—show pleasantness on both sides. Seacole told him of her encounter with Nightingale at the Barrack Hospital: "You must know, M Soyer, that Miss Nightingale is very fond of me. When I passed through Scutari, she very kindly gave me board and lodging." When he related Seacole's inquiries to Nightingale, she replied "with a smile: 'I should like to see her before she leaves, as I hear she has done a deal of good for the poor soldiers.'" Nightingale, however, did not want her nurses associating with Seacole, as she wrote to her brother-in-law.

Seacole often went out to the troops as a sutler, selling her provisions near the British camp at Kadikoi, and nursing casualties brought out from the trenches around Sevastopol or from the Tchernaya valley. She was widely known to the British Army as "Mother Seacole".

Apart from serving officers at the British Hotel, Seacole also provided catering for spectators at the battles, and spent time on Cathcart's Hill, some north of the British Hotel, as an observer. On one occasion, attending wounded troops under fire, she dislocated her right thumb, an injury which never healed entirely.Seacole, Chapter XVI. In a dispatch written on 14 September 1855,

Seacole often went out to the troops as a sutler, selling her provisions near the British camp at Kadikoi, and nursing casualties brought out from the trenches around Sevastopol or from the Tchernaya valley. She was widely known to the British Army as "Mother Seacole".

Apart from serving officers at the British Hotel, Seacole also provided catering for spectators at the battles, and spent time on Cathcart's Hill, some north of the British Hotel, as an observer. On one occasion, attending wounded troops under fire, she dislocated her right thumb, an injury which never healed entirely.Seacole, Chapter XVI. In a dispatch written on 14 September 1855, William Howard Russell

Sir William Howard Russell, (28 March 182011 February 1907) was an Irish reporter with ''The Times'', and is considered to have been one of the first modern war correspondents. He spent 22 months covering the Crimean War, including the Sieg ...

, special correspondent of ''The Times'', wrote that she was a "warm and successful physician, who doctors and cures all manner of men with extraordinary success. She is always in attendance near the battlefield to aid the wounded and has earned many a poor fellow's blessing." Russell also wrote that she "redeemed the name of sutler", and another that she was "both a Miss Nightingale and a hef. Seacole made a point of wearing brightly coloured, and highly conspicuous, clothing—often bright blue, or yellow, with ribbons in contrasting colours. While Lady Alicia Blackwood later recalled that Seacole had "... personally spared no pains and no exertion to visit the field of woe, and minister with her own hands such things as could comfort or alleviate the suffering of those around her; freely giving to such as could not pay ...".

Her peers, though wary at first, soon found out how important Seacole was for both medical assistance and morale. One British medical officer described Seacole in his memoir as "The acquaintance of a celebrated person, Mrs. Seacole, a coloured women who out of the goodness of her heart and at her own expense, supplied hot tea to the poor sufferers ounded men being transported from the peninsula to the hospital at Scutari while they are waiting to be lifted into the boats…. She did not spare herself if she could do any good to the suffering soldiers. In rain and snow, in storm and tempest, day after day she was at her self-chosen post with her stove and kettle, in any shelter she could find, brewing tea for all who wanted it, and they were many. Sometimes more than 200 sick would be embarked in one day, but Mrs. Seacole was always equal, to the occasion". But Seacole did more than carry tea to the suffering soldiers. She often carried bags of lint, bandages, needles and thread to tend to the wounds of soldiers.

In late August, Seacole was on the route to Cathcart's Hill for the final assault on Sevastopol on 7 September 1855. French troops led the storming, but the British were beaten back. By dawn on Sunday 9 September, the city was burning out of control, and it was clear that it had fallen: the Russians retreated to fortifications to the north of the harbour. Later in the day, Seacole fulfilled a bet, and became the first British woman to enter Sevastopol after it fell.Seacole, Chapter XVII. Having obtained a pass, she toured the broken town, bearing refreshments and visiting the crowded hospital by the docks, containing thousands of dead and dying Russians. Her foreign appearance led to her being stopped by French looters, but she was rescued by a passing officer. She looted some items from the city, including a church bell, an altar candle, and a three-metre (10 ft) long painting of the Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone (; ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer-songwriter and actress. Widely dubbed the " Queen of Pop", Madonna has been noted for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, songwriting, a ...

.

After the fall of Sevastopol, hostilities continued in a desultory fashion.Seacole, Chapter XVIII. The business of Seacole and Day prospered in the interim period, with the officers taking the opportunity to enjoy themselves in the quieter days. There were theatrical performances and horse-racing events for which Seacole provided catering.

Seacole was joined by a 14-year-old girl, Sarah, also known as Sally. Soyer described her as "the Egyptian beauty, Mrs Seacole's daughter Sarah", with blue eyes and dark hair. Nightingale alleged that Sarah was the illegitimate offspring of Seacole and Colonel Henry Bunbury. However, there is no evidence that Bunbury met Seacole, or even visited Jamaica, at a time when she would have been nursing her ailing husband. Ramdin speculates that Thomas Day could have been Sarah's father, pointing to the unlikely coincidences of their meeting in Panama and then in England, and their unusual business partnership in Crimea.

Peace talks began in Paris in early 1856, and friendly relations opened between the Allies and the Russians, with a lively trade across the River Tchernaya.Seacole, Chapter XIX. The Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 March 1856, after which the soldiers left Crimea. Seacole was in a difficult financial position, her business was full of unsaleable provisions, new goods were arriving daily, and creditors were demanding payment. She attempted to sell as much as possible before the soldiers left, but she was forced to auction many expensive goods for lower-than-expected prices to the Russians who were returning to their homes. The evacuation of the Allied armies was formally completed at Balaclava on 9 July 1856, with Seacole "... conspicuous in the foreground ... dressed in a plaid riding-habit ...". Seacole was one of the last to leave Crimea, returning to England "poorer than heleft it". Though she had left poorer, her impact on the soldiers was invaluable to the soldiers she treated, changing their perceptions about her as described in ''the Illustrated London News:'' "Perhaps at first the authorities looked askant at the woman-volunteer; but they soon found her worth and utility; and from that time until the British army left the Crimea, Mother Seacole was a household word in the camp...In her store on Spring Hill she attended many patients, cared for many sick, and earned the good will and gratitude of hundreds".Literature Review. ''The Illustrated London News''. Elm House, 25 July 1857, pg. 105.

Sociology professor Lynn McDonald is co-founder of The Nightingale Society, which promotes the legacy of Nightingale, who did not see eye-to-eye with Seacole. McDonald believes that Seacole's role in the Crimean War was overplayed:

However, historians maintain that claims dismissing Seacole's work as mainly "tea and lemonade" do a disservice to the tradition of Jamaican "doctresses", such as Seacole's mother, Cubah Cornwallis

Cubah Cornwallis (died 1848) (often spelled Coubah, Couba, Cooba or Cuba) was a nurse or "doctress" and Obeah woman who lived in the colony of Jamaica during the late 18th and 19th century.

Early life

Little is known of her early life although re ...

, Sarah Adams and Grace Donne, who all used herbal remedies and hygienic practices in the late eighteenth century, long before Nightingale took up the mantle. Social historian Jane Robinson argues in her book ''Mary Seacole: The Black Woman who invented Modern Nursing'' that Seacole was a huge success, and she became known and loved by everyone from the rank and file to the royal family. Mark Bostridge

Mark Bostridge is a British writer and critic, known for his historical biographies.

He was educated at Westminster School and read Modern History at St Anne's College, Oxford, from 1979 to 1984. At Oxford, he was awarded the Gladstone Memorial P ...

pointed out that Seacole's experience far outstripped Nightingale's, and that the Jamaican's work comprised preparing medicines, diagnosis, and minor surgery. ''The Times'' war correspondent William Howard Russell

Sir William Howard Russell, (28 March 182011 February 1907) was an Irish reporter with ''The Times'', and is considered to have been one of the first modern war correspondents. He spent 22 months covering the Crimean War, including the Sieg ...

spoke highly of Seacole's skill as a healer, writing "A more tender or skilful hand about a wound or a broken limb could not be found among our best surgeons."

Back in London, 1856–60

After the end of the war, Seacole returned to England destitute and in poor health. In the conclusion to her autobiography, she records that she "took the opportunity" to visit "yet other lands" on her return journey, although Robinson attributes this to her impecunious state requiring a roundabout trip. She arrived in August 1856 and opened a canteen with Day at

After the end of the war, Seacole returned to England destitute and in poor health. In the conclusion to her autobiography, she records that she "took the opportunity" to visit "yet other lands" on her return journey, although Robinson attributes this to her impecunious state requiring a roundabout trip. She arrived in August 1856 and opened a canteen with Day at Aldershot

Aldershot () is a town in Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme northeast corner of the county, southwest of London. The area is administered by Rushmoor Borough Council. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Alder ...

, but the venture failed through lack of funds. She attended a celebratory dinner for 2,000 soldiers at Royal Surrey Gardens

Royal Surrey Gardens were pleasure gardens in Newington, Surrey, London in the Victorian period, slightly east of The Oval. The gardens occupied about to the east side of Kennington Park Road, including a lake of about . It was the site of Su ...

in Kennington

Kennington is a district in south London, England. It is mainly within the London Borough of Lambeth, running along the boundary with the London Borough of Southwark, a boundary which can be discerned from the early medieval period between the ...

on 25 August 1856, at which Nightingale was chief guest of honour. Reports in ''The Times'' on 26 August and ''News of the World

The ''News of the World'' was a weekly national red top tabloid newspaper published every Sunday in the United Kingdom from 1843 to 2011. It was at one time the world's highest-selling English-language newspaper, and at closure still had one ...

'' on 31 August indicate that Seacole was also fêted by the huge crowds, with two "burly" sergeants protecting her from the pressure of the crowd. However, creditors who had supplied her firm in Crimea were in pursuit. She was forced to move to 1, Tavistock Street, Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

in increasingly dire financial straits. The Bankruptcy Court in Basinghall Street declared her bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor ...

on 7 November 1856. Robinson speculates that Seacole's business problems may have been caused in part by her partner, Day, who dabbled in horse trading and may have set up as an unofficial bank, cashing debts. 4

At about this time, Seacole began to wear military medals. These are mentioned in an account of her appearance in the bankruptcy court in November 1856.Robinson, p.167. A bust by George Kelly, based on an original by Count Gleichen from around 1871, depicts her wearing four medals, three of which have been identified as the British Crimea Medal

The Crimea Medal was a campaign medal approved on 15 December 1854, for issue to officers and men of British units (land and naval) which fought in the Crimean War of 1854–56 against Russia. The medal was awarded with the British version of th ...

, the French Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

and the Turkish Order of the Medjidie medal. Robinson says that one is "apparently" a Sardinian award (Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

having joined Britain and France in supporting Turkey against Russia in the war). The Jamaican '' Daily Gleaner'' stated in her obituary on 9 June 1881 that she had also received a Russian medal, but it has not been identified. However, no formal notice of her award exists in the ''London Gazette

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major se ...

'', and it seems unlikely that Seacole was formally rewarded for her actions in Crimea; rather, she may have bought miniature or "dress" medals to display her support and affection for her "sons" in the Army.

Seacole's plight was highlighted in the British press. As a consequence a fund was set up, to which many prominent people donated money, and on 30 January 1857, she and Day were granted certificates discharging them from bankruptcy. Day left for the Antipodes to seek new opportunities, but Seacole's funds remained low. She moved from Tavistock Street to cheaper lodgings at 14 Soho Square in early 1857, triggering a plea for subscriptions from ''Punch

Punch commonly refers to:

* Punch (combat), a strike made using the hand closed into a fist

* Punch (drink), a wide assortment of drinks, non-alcoholic or alcoholic, generally containing fruit or fruit juice

Punch may also refer to:

Places

* Pu ...

'' on 2 May. However, in ''Punch''s 30 May edition, she was heavily criticised for a letter she sent begging her favorite magazine, which she claimed to have often read to her British Crimean War patients, to assist her in gaining donations. After quoting her letter in full the magazine provides a satiric cartoon of the activity she describes, captioned "Our Own Vivandière," describing Seacole as a female sutler. The article observes: "It will be evident, from the foregoing, that Mother Seacole has sunk much lower in the world, and is also in danger of rising much higher in it, than is consistent with the honour of the British army, and the generosity of the British public." While urging the public to donate, the commentary's tone can be read as ironic: "Who would give a guinea to see a mimic-sutler woman, and a foreigner, frisk and amble about on the stage, when he might bestow the money on a genuine English one, reduced to a two-pair back, and in imminent danger of being obliged to climb into an attic?"

In researching his biography of

In researching his biography of Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during the Crimean War ...

, the first major biography in fifty years, Mark Bostridge

Mark Bostridge is a British writer and critic, known for his historical biographies.

He was educated at Westminster School and read Modern History at St Anne's College, Oxford, from 1979 to 1984. At Oxford, he was awarded the Gladstone Memorial P ...

uncovered a letter in the archive at the home of Nightingale's sister Parthenope, which showed that Nightingale had made a contribution to Seacole's fund, indicating that she saw value at that time in Seacole's work in the Crimea.

Further fund-raising and literary mentions kept Seacole in the public eye. In May 1857 she wanted to travel to India, to minister to the wounded of the Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against the rule of the British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion began on 10 May 1857 in the for ...

, but she was dissuaded by both the new Secretary of War, Lord Panmure

Fox Maule-Ramsay, 11th Earl of Dalhousie, (22 April 18016 July 1874), known as Fox Maule before 1852, as The Lord Panmure between 1852 and 1860, was a British politician.

Ancestry

Dalhousie was the eldest son of William Maule, 1st Baron Pan ...

, and her financial troubles. Fund-raising activities included the "Seacole Fund Grand Military Festival", which was held at the Royal Surrey Gardens

Royal Surrey Gardens were pleasure gardens in Newington, Surrey, London in the Victorian period, slightly east of The Oval. The gardens occupied about to the east side of Kennington Park Road, including a lake of about . It was the site of Su ...

, from Monday 27 July to Thursday 30 July 1857. This successful event was supported by many military men, including Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Lord Rokeby (who had commanded the 1st Division in Crimea) and Lord George Paget; more than 1,000 artists performed, including 11 military bands and an orchestra conducted by Louis Antoine Jullien

Louis George Maurice Adolphe Roche Albert Abel Antonio Alexandre Noë Jean Lucien Daniel Eugène Joseph-le-brun Joseph-Barême Thomas Thomas Thomas-Thomas Pierre Arbon Pierre-Maurel Barthélemi Artus Alphonse Bertrand Dieudonné Emanuel Josué V ...

, which was attended by a crowd of circa 40,000. The one-shilling entrance charge was quintupled for the first night, and halved for the Tuesday performance. However, production costs had been high and the Royal Surrey Gardens Company was itself having financial problems. It became insolvent immediately after the festival, and as a result Seacole only received £57, one quarter of the profits from the event. When eventually the financial affairs of the ruined Company were resolved, in March 1858, the Indian Mutiny was over. Writing of his 1859 journey to the West Indies, the British novelist Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

described visiting Mrs. Seacole's sister's hotel in Kingston in his ''The West Indies and the Spanish Main'' (Chapman & Hall, 1850). Besides remarking on the pride of the servants and their firm insistence that they be treated politely by guests, Trollope remarked that his hostess, "though clean and reasonable in her charges, clung with touching tenderness to the idea that beefsteak and onions, and bread and cheese and beer, comprised the only diet proper to an Englishman."

''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands''

A 200-page autobiographical account of her travels was published in July 1857 by James Blackwood as ''Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands'', the first autobiography written by a black woman in Britain. Priced at oneshilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence ...

and six pence

A penny is a coin ( pennies) or a unit of currency (pl. pence) in various countries. Borrowed from the Carolingian denarius (hence its former abbreviation d.), it is usually the smallest denomination within a currency system. Presently, it is t ...

(1/6) a copy, the cover bears a striking portrait of Seacole in red, yellow and black ink. Robinson speculates that she dictated the work to an editor, identified in the book only as W.J.S., who improved her grammar and orthography. In the work Seacole deals with the first 39 years of her life in one short chapter. She then expends six chapters on her few years in Panama, before using the following 12 chapters to detail her exploits in Crimea. She avoids mention of the names of her parents and precise date of birth. In the first chapter, she talks about how her practice of medicine began on animals, such as cats and dogs. Most of the animals caught diseases from their owners, and she would cure them with homemade remedies. Within the book, Mrs. Seacole discusses how when she returned from the Crimean War she was poor, whereas others in her same position returned to England rich. Mrs. Seacole shares the respect she gained from the men in the Crimean War. The soldiers would refer to her as "mother" and would ensure her safety by personally guarding her on the battlefield. A short final "Conclusion" deals with her return to England, and lists supporters of her fund-raising effort, including Rokeby, Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar

Prince William Augustus Edward of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, , PC(Ire) (11 October 1823 – 16 November 1902) was a British military officer of German parents. After a career in the Grenadier Guards, he became Major General commanding the Brigade ...

, the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister ...

, the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle ...

, William Russell, and other prominent men in the military. Also within the Conclusion, she describes all of her career adventures experienced in the Crimean War as pride and pleasure. The book was dedicated to Major-General Lord Rokeby, commander of the First Division. In a brief preface

__NOTOC__

A preface () or proem () is an introduction to a book or other literary work written by the work's author. An introductory essay written by a different person is a '' foreword'' and precedes an author's preface. The preface often close ...

, the ''Times'' correspondent William Howard Russell wrote, "I have witnessed her devotion and her courage ... and I trust that England will never forget one who has nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead."

The ''Illustrated London News'' received the autobiography favourably agreeing with the statements made in the preface "If singleness of heart, true charity and Christian works – of trials and sufferings, dangers and perils, encountered boldly by a helpless women on her errand of mercy in the camp and in the battlefield can excite sympathy or move curiosity, Mary Seacole will have many friends and many readers".

In 2017 Robert McCrum

John Robert McCrum (born 7 July 1953) is an English writer and editor, holding senior editorial positions at Faber and Faber over seventeen years, followed by a long association with ''The Observer''.

Early life

The son of Michael William McC ...

chose it as one of the 100 best nonfiction books, calling it "gloriously entertaining".

Later life, 1860–81

Seacole joined the

Seacole joined the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

circa 1860, and returned to a Jamaica changed in her absence as it faced economic downturn. She became a prominent figure in the country. However, by 1867 she was again running short of money, and the Seacole fund was resurrected in London, with new patrons including the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

, the Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the city of Edinburgh in Scotland, was a substantive title that has been created three times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not prod ...

, the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

, and many other senior military officers. The fund burgeoned, and Seacole was able to buy land on Duke Street in Kingston, near New Blundell Hall, where she built a bungalow

A bungalow is a small house or cottage that is either single-story or has a second story built into a sloping roof (usually with dormer windows), and may be surrounded by wide verandas.

The first house in England that was classified as a b ...

as her new home, plus a larger property to rent out.

By 1870, Seacole was back in London, living at 40 Upper Berkley St., St. Marylebone. Robinson speculates that she was drawn back by the prospect of rendering medical assistance in the Franco-Prussian War. It seems likely that she approached Sir Harry Verney (the husband of Florence Nightingale's sister Parthenope) Member of Parliament for Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

who was closely involved in the British National Society for the Relief of the Sick and Wounded. It was at this time Nightingale wrote her letter to Verney insinuating that Seacole had kept a "bad house" in Crimea, and was responsible for "much drunkenness and improper conduct".

In London, Seacole joined the periphery of the royal circle. Prince Victor (a nephew of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

; as a young Lieutenant he had been one of Seacole's customers in Crimea) carved a marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

bust

Bust commonly refers to:

* A woman's breasts

* Bust (sculpture), of head and shoulders

* An arrest

Bust may also refer to:

Places

* Bust, Bas-Rhin, a city in France

*Lashkargah, Afghanistan, known as Bust historically

Media

* ''Bust'' (magazin ...

of her in 1871 that was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1872. Seacole also became personal masseuse

Massage is the manipulation of the body's soft tissues. Massage techniques are commonly applied with hands, fingers, elbows, knees, forearms, feet or a device. The purpose of massage is generally for the treatment of body stress or pain. In E ...

to the Princess of Wales

Princess of Wales (Welsh: ''Tywysoges Cymru'') is a courtesy title used since the 14th century by the wife of the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. The current title-holder is Catherine (née Middleton).

The title was fi ...

who suffered with white leg and rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including ar ...

.