Maritime history of Europe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Maritime history of Europe represents the era of recorded human interaction with the sea in the northwestern region of

The Maritime history of Europe represents the era of recorded human interaction with the sea in the northwestern region of

Egyptian sources mention regular shipments of copper from the island of

Egyptian sources mention regular shipments of copper from the island of

During the

During the

Also called the

Also called the

The

The

Around 1300, Venice began to develop the great galley of commerce, the ‘’galea grossa’’. It grew to carry a crew of more than 200 and weighed as much as 250 tons. These galleys took passengers and goods to

Around 1300, Venice began to develop the great galley of commerce, the ‘’galea grossa’’. It grew to carry a crew of more than 200 and weighed as much as 250 tons. These galleys took passengers and goods to

From the sixth to the eighteenth centuries, the maritime history of Europe had a profound impact on the rest of the world. The broadside-cannoned full-rigged sixteenth-century sailing ship provided the continent with a weapon to dominate the world.

During this time period, Europeans made remarkable inroads in maritime

From the sixth to the eighteenth centuries, the maritime history of Europe had a profound impact on the rest of the world. The broadside-cannoned full-rigged sixteenth-century sailing ship provided the continent with a weapon to dominate the world.

During this time period, Europeans made remarkable inroads in maritime  They developed new

They developed new

July 1779 saw the start of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, an attempt by France and Spain to wrest control of Gibraltar from the British. The

July 1779 saw the start of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, an attempt by France and Spain to wrest control of Gibraltar from the British. The

The Pharos of

The Pharos of

Early Maritime Maps Online

{{DEFAULTSORT:Maritime History Of Europe History of Europe

The Maritime history of Europe represents the era of recorded human interaction with the sea in the northwestern region of

The Maritime history of Europe represents the era of recorded human interaction with the sea in the northwestern region of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

in areas that include shipping

Freight transport, also referred as ''Freight Forwarding'', is the physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo. The term shipping originally referred to transport by sea but in American English, it has been ...

and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to bef ...

, shipwrecks

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. Shipwrecking may be intentional or unintentional. Angela Croome reported in January 1999 that there were approximately ...

, naval battle

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

s, and military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

installations and lighthouses

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

constructed to protect or aid navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation ...

and the development of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

.

Europe is situated between several navigable sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

s and intersected by navigable river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of ...

s running into them in a way which greatly facilitated the influence of maritime traffic and commerce. Great battles have been fought in the seas off of Europe that changed the course of history forever, including the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, the Battle of Gravelines at the eastern end of the English Channel in the summer of 1588, in which the “Invincible” Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an ar ...

was defeated, the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vice ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

’s U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

war.

Ancient times

Egyptian sources mention regular shipments of copper from the island of

Egyptian sources mention regular shipments of copper from the island of Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

, that arrived at the city of Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 8 ...

as early as 2,600 years BCE. The Minoans of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

are the earliest known European seafarers of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Little is known of their ships, but they reportedly traded pottery as far west as Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. According to the historian Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, by 1,900 years BCE. their King Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos (; grc-gre, Μίνως, ) was a King of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every nine years, he made King Aegeus pick seven young boys and seven young girls to be sent to Daedalus's creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten ...

commanded a navy and conquered the islands of the Aegean. The Mycenaeans would obtain maritime hegemony in the region around 1,600 BCE and hold it until the attacks of the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

, that disrupted the maritime culture and the naval balance of power in the Eastern Mediterranean

Eastern Mediterranean is a loose definition of the eastern approximate half, or third, of the Mediterranean Sea, often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea.

It typically embraces all of that sea's coastal zones, referring to commun ...

during the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near ...

between 1,200 and 900 years BCE.

During the following centuries the ancient Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

navies first began to use ships with two banks of oars and by the 6th century BCE. the three banked trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

had been adopted by all sea-faring Poleis. Alongside the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns, who since around 1,200 BCE. had settled in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

and Northern Africa, Greek trading fleets and navies dominated the Mediterranean until the ascent of Rome in the third and second century BCE.

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

ships, methods of engagement, movement and command under the Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

Strategos

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Helleni ...

Themistocles

Themistocles (; grc-gre, Θεμιστοκλῆς; c. 524–459 BC) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As ...

proved to be highly effective during the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

(499 to 449 BCE). Relatively small Greek forces successfully delayed the Persian fleet in a series of naval engagements in 480 BCE. Naval conflict culminated in the straits between the port of Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saro ...

and Salamis Island

Salamis ( ; el, Σαλαμίνα, Salamína; grc, label= Ancient and Katharevousa, Σαλαμίς, Salamís) is the largest Greek island in the Saronic Gulf, about off-coast from Piraeus and about west of central Athens. The chief city, S ...

during the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

(September 480 BCE), when 371 Greek trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizat ...

s and pentekonter

The penteconter (alt. spelling pentekonter, pentaconter, pentecontor or pentekontor; el, πεντηκόντερος, ''pentēkónteros'', "fifty-oared"), plural penteconters, was an ancient Greek galley in use since the archaic period.

In an ...

s defeated King Xerxes' Persian fleet of over 1,200 ships, that included Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

n, Egyptian, Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern co ...

n and Cypriot contingents. The city of Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, that had risen to naval supremacy among the Greek poleis was defeated in the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

and lost its fleet against the Peloponnesian League

The Peloponnesian League was an alliance of ancient Greek city-states, dominated by Sparta and centred on the Peloponnese, which lasted from c.550 to 366 BC. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 ...

under Lysander

Lysander (; grc-gre, Λύσανδρος ; died 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an en ...

in the Battle of Aegospotami

The Battle of Aegospotami was a naval confrontation that took place in 405 BC and was the last major battle of the Peloponnesian War. In the battle, a Spartan fleet under Lysander destroyed the Athenian navy. This effectively ended the war, since ...

in 405 BCE.

Around 325 B.C. Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης ''Pythéas ho Massaliōtēs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320–306 BC) was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colony ...

, a Greek geographer and explorer undertook a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe (modern-day Great Britain and Ireland) and beyond. In his account ''On The Ocean'' (Τὰ περὶ τοῦ Ὠκεανοῦ), that is only known through the writings of Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

, he introduces the idea of the land of Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shetland, northern Scotland, the island of Saar ...

and describes Celtic and Germanic tribes, the Arctic, polar ice and the midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon that occurs in the summer months in places north of the Arctic Circle or south of the Antarctic Circle, when the Sun remains visible at the local midnight. When the midnight sun is seen in the Arctic, ...

.

Maritime history of Republican and Imperial Rome

During the

During the First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

, the admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

conceived new and progressive ways of fleet construction, development and composition in order to successfully engage the Carthaginian navy. Victories at the Battle of Mylae

The Battle of Mylae took place in 260 BC during the First Punic War and was the first real naval battle between Carthage and the Roman Republic. This battle was key in the Roman victory of Mylae (present-day Milazzo) as well as Sicily itself. It ...

, the Battle of Cape Ecnomus, the Battle of Cape Hermaeum and the Battle of the Aegates

The Battle of the Aegates was a naval battle fought on 10 March 241 BC between the fleets of Carthage and Rome during the First Punic War. It took place among the Aegates Islands, off the western coast of the island of Sicily. The Carthagin ...

encouraged the Romans to pursue naval-based warfare and strategies in order to push the center of combat to the Carthaginian heartland in North Africa.

By the end of the Macedonian Wars in the latter half of the 2nd century BC, Roman control over the Aegean sea was undisputed and full hegemony over the entire Mediterranean Sea, now referred to as '' Mare Nostrum'' ("our sea") had been established.

Roman galleys

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be use ...

helped to build the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

. The empires’ struggle with Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

inspired them to build and to fight in war galleys, but the galleys did not have much cargo space, so “round ships” were constructed for trade, especially with Egypt. Many of these ships reached in length and were capable of carrying over a thousand tons of cargo. These ships used sail power alone to haul commodities in the mediterranean. The volume of trade that the Roman merchant fleet carried was larger than any other until the industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. We know quite a bit about these round ships, since Romans, like Egyptians and Greeks, left records in stone, sometimes even on a sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Gre ...

.

There were many shipwrecks of Roman vessels, which can be explained by the very large number of trading vessels during Roman times since the volume of sea trade in the mediterranean reached a quantity to be only equaled in the 19th century. This greatly increased the number of shipwrecks.

Byzantine Empire

The western Mediterranean came under the control of the barbarians, after theirinvasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing ...

split the Empire in two, while Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

dominated the eastern half of the sea. The eastern empire lasted until 1453, such was the efficiency of the Byzantine navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

, with its fleets armed with Byzantine fire (or Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon used by the Eastern Roman Empire beginning . Used to set fire to enemy ships, it consisted of a combustible compound emitted by a flame-throwing weapon. Some historians believe it could be ignited on contact w ...

), a mixture of naphtha

Naphtha ( or ) is a flammable liquid hydrocarbon mixture.

Mixtures labelled ''naphtha'' have been produced from natural gas condensates, petroleum distillates, and the distillation of coal tar and peat. In different industries and regions ' ...

oil and saltpetre

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and nitra ...

, fired through tubes in the bows of the ship. Enemy ships were often afraid to get too close to the Byzantine fleet, since the liquid fire gave the Byzantines a considerable advantage.

The Viking Age

Also called the

Also called the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

, the Norsemen raided towns and villages along the coasts of the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

, Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

, as far south as Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

and even attacked Pisa

Pisa ( , or ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for its leaning tower, the ci ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

in 860. They sailed up the Seine River

)

, mouth_location = Le Havre/Honfleur

, mouth_coordinates =

, mouth_elevation =

, progression =

, river_system = Seine basin

, basin_size =

, tributaries_left = Yonne, Loing, Eure, Risle

, tributaries ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, settled Normandy (which derives its name from the Norsemen), and settled Dublin after invading Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

. Varangians

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

were more concerned with trading than raiding, and sailed along Russian rivers and opened commercial routes to the " Online Etymo ...

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

as well as the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

.

The Vikings were the best naval architects of their day, and the Viking longship

Longships were a type of specialised Scandinavian warships that have a long history in Scandinavia, with their existence being archaeologically proven and documented from at least the fourth century BC. Originally invented and used by the Nor ...

was both large and versatile. A longship found at Oseberg, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of ...

, was , more than wide, and had a draft of only . The shallow draft enabled them to navigate far inland in shallow rivers. Later on during the Viking period some of the ships were reported to be over long.

"From the fury of the Norsemen, good Lord, deliver us," has entered apocryphal knowledge as a common prayer among the people of western Europe during the period of the Norse raiders from the late 8th century to the 11th century. According to the website ''Viking Answer Lady'',

which in turn cites Magnus Magnusson's ''Vikings!'' as its reference,

No 9th century text has ever been discovered containing these words, although numerous medieval litanies and prayers contain general formulas for deliverance against unnamed enemies. The closest documentable phrase is a single sentence, taken from an antiphony for churches dedicated to St. Vaast orSt. Medard Saint Medardus or St Medard (French: ''Médard'' or ''Méard'') (ca. 456–545) was the Bishop of Noyon. He moved the seat of the diocese from Vermand to Noviomagus Veromanduorum (modern Noyon) in northern France. Medardus was one of the most h ...: Summa pia gratia nostra conservando corpora et custodita, de gente fera Normannica nos libera, quae nostra vastat, Deus, regna, ”Oh highest, pious grace, free us, oh God, by preserving our bodies and those in our keeping from the cruel Norse people who ravage our realms.”.

The Hanseatic League

The

The Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label= Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

was a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchant guilds of towns and cities in northern and central Europe that established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

and most of Northern Europe between the 13th and 17th centuries.

Although trading alliances in the region were forming as early as 1157, the town of Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

did not form an alliance with Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

(which controlled access to salt routes from Lüneburg

Lüneburg (officially the ''Hanseatic City of Lüneburg'', German: ''Hansestadt Lüneburg'', , Low German ''Lümborg'', Latin ''Luneburgum'' or ''Lunaburgum'', Old High German ''Luneburc'', Old Saxon ''Hliuni'', Polabian ''Glain''), also called ...

), until 1241.

Trade was carried on chiefly by sea in order to escape tolls and political barriers, and at the end of the 15th century the Hanseatic League controlled some 60,000 tons of shipping. Although compasses were commonly being used in the Mediterranean during this period, the captains of Hanseatic vessels seemed slow to adopt the new technology, which put them in greater danger of wrecking. They also had to deal with pirates. During its zenith the alliance maintained trading posts and kontors in virtually all cities between London and Edinburgh in the west to Novgorod in the east and Bergen in Norway.

The League's power declined after 1450 due to a number of factors, such as the 15th-century crisis, the territorial lords' shifting policies towards greater commercial control, the silver crisis and when the great herring

Herring are forage fish, mostly belonging to the family of Clupeidae.

Herring often move in large schools around fishing banks and near the coast, found particularly in shallow, temperate waters of the North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocean ...

shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s disappeared in the Baltic. During the late 16th century and early 17th century, the League fell apart, as it was unable to deal with its own internal struggles, the rise of Swedish, Dutch and English merchants, and the social and political changes that accompanied the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Although a tight-fisted monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

, the League's need for more cargo space led to new designs in shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to bef ...

, and its free association of about 160 towns and villages was a historically unique economic

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

alliance that showed the benefits of well-regulated commerce

Commerce is the large-scale organized system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions directly and indirectly related to the exchange (buying and selling) of goods and services among two or more parties within local, regional, natio ...

.

Republic of Venice

Around 1300, Venice began to develop the great galley of commerce, the ‘’galea grossa’’. It grew to carry a crew of more than 200 and weighed as much as 250 tons. These galleys took passengers and goods to

Around 1300, Venice began to develop the great galley of commerce, the ‘’galea grossa’’. It grew to carry a crew of more than 200 and weighed as much as 250 tons. These galleys took passengers and goods to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

(now Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

), and to Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, and returned to Venice carrying luxury items. A sea route to the Indies discovered by Portugal signaled an end to the glory days of Venice's merchant galleys and spice trade, but the war galleys (or fighting galleys) lived on. The war galleys were mostly manned by prisoners of war or convicts, who were chained to benches, usually three to six per oar.

More than 3,000 Venetian merchant ships were in operation by the year 1450. The trading empire of the Republic of Venice lasted longer than any other in history, and even merchants vessels were required to carry weapons and passengers were expected to be armed and ready to fight. From the beginning of the 13th century until the end of the 18th century, the Republic ruled the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

, the Aegean and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

s. The Republic of Genoa was Venice's main rival, and many wars were fought between them. In 1298 the Genoese destroyed the Venetian fleet at Curzola, but were themselves defeated in 1354 at Sapienza in Greece.

The European Age of Discovery (1400–1600)

TheAge of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafa ...

started with the Portuguese navigators, where Prince Henry the Navigator

''Dom'' Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu (4 March 1394 – 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator ( pt, Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador), was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15t ...

started a maritime school in Portugal, eventually leading to new shipbuilding technologies including the caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing w ...

, the carrack

A carrack (; ; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal. Evolved from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for European trade ...

and the galleon

Galleons were large, multi-decked sailing ships first used as armed cargo carriers by European states from the 16th to 18th centuries during the age of sail and were the principal vessels drafted for use as warships until the Anglo-Dutch ...

. The Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the ...

led the Portuguese Kingdom to discover and map more of the globe, such as the remarkable voyage to find the sea route to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

via the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

. Initially Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( 1450 – 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lay in the o ...

left Portugal and rounded the Cape of Good Hope, with Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

reaching the southern tip of Africa and on-wards to India. It was the first time in history that humans had navigated from Europe around Africa to Asia, though the Fra Mauro map suggests that ships from India had crossed the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

in 1420. It led to the discovery of Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and South America, and the first circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the ...

around the world, with the Portuguese nobleman Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

, sailing around the world, across the entire Pacific Ocean for the first time.

At the beginning of the 16th century, sea clashes in the Indian Ocean as the decisive Battle of Diu, in 1509, marked a turning point in history: the shift from the Mediterranean and from the relatively isolated seas, disputed in antiquity and in the Middle Ages, to the oceans and to the European hegemony on a global scale.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

set sail in ''Santa Maria'' on what is probably history's most well known voyage of discovery on August 3, 1492. Leaving from the town of Palos, in southern Spain, Columbus headed west. After a brief stop in the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

for provisions and repairs, he set out for Asia. He reached San Salvador first, it is believed, (easternmost of the Bahamas) in October, and then sailed past Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, still searching for Asia. He returned home in 1493 to a hero's welcome, and within six months had 1,500 men and 17 vessels at his command.

The year 1571 saw the last great battle between galleys, when more than 400 Turkish and Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

vessels engaged each other on the Gulf of Patras. The Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states (comprising Spain and its Italian territories, several independent Italian states, and the Soverei ...

as it was called, saw some 38,000 men perish. Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

, author of ''Don Quixote'', was wounded during the battle.

In April 1587, Sir Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 158 ...

burned 37 Spanish ships in the harbor at Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, in southern Spain.

The publication of Jan Huygen van Linschoten

Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563 – 8 February 1611) was a Dutch merchant, trader and historian.

He travelled extensively along the East Indies regions under Portuguese influence and served as the archbishop's secretary in Goa between 1583 ...

's book ''Voyages'' provided a significant turning point in Europe's maritime history. Before the publication of this book, knowledge of the sea route to the Far East had been well guarded by the Portuguese for over a century. ''Voyages'' was published in several languages, including English and German (published in 1598), Latin (1599), and French (1610). Widely read by Europeans, the original Dutch edition and the French translation had second editions published.

Once knowledge of the sea route became available to all Europeans, more ships headed to East Asia. A Dutch fleet embarked on a voyage to India using Linschoten's charts in 1595. (The Dutch version of his book was published in 1596, but his sea charts had been published the previous year). The publication of the nautical maps enabled the Dutch and British East India companies to break the trade monopoly Portugal held with the East Indies. Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Europe was ushered into the age of discovery in large part thanks to his work.

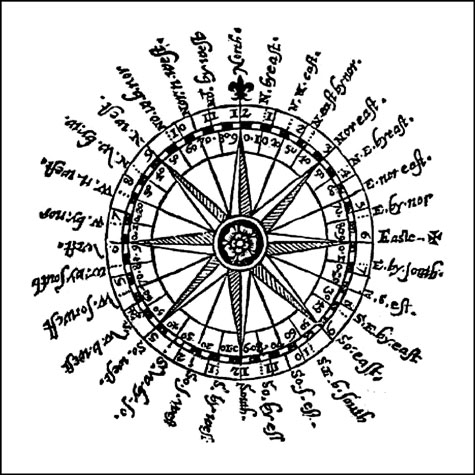

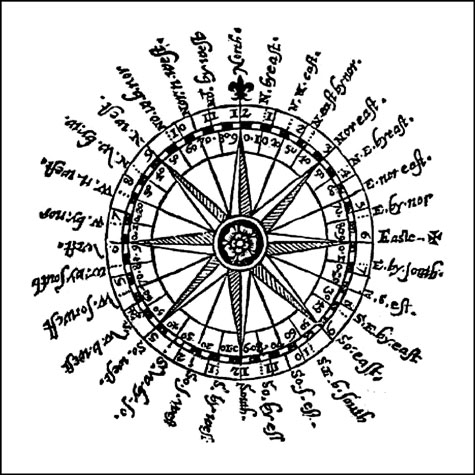

European innovations

innovation

Innovation is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services. ISO TC 279 in the standard ISO 56000:2020 defines innovation as "a new or changed enti ...

s. These innovations enabled them to expand overseas and set up colonies, most notably during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They developed new

They developed new sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails ma ...

arrangements for ships, skeleton-based shipbuilding, the Western “galea” (at the end of the 11th century), sophisticated navigational instruments, and detailed chart

A chart (sometimes known as a graph) is a graphical representation for data visualization, in which "the data is represented by symbols, such as bars in a bar chart, lines in a line chart, or slices in a pie chart". A chart can represent ...

s. After Isaac Newton published the ''Principia'', navigation was transformed. Starting in 1670, the entire world was measured using essentially modern latitude instruments and the best available clocks. In 1730 the sextant was invented and navigators rapidly replaced their astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

s.

Barbary pirates

For several centuries, from about the time of theCrusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

until the early 19th century, the Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli. This area was known in Europe ...

of northern Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

preyed on ships in the western Mediterranean Sea. In 1816, the Royal Navy, with assistance from the Dutch, destroyed the Barbary fleet in the port of Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques d ...

. The best-known pirate of this period may have been Barbarossa, the nickname of Khair ad Din, an Ottoman-Turkish admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

and privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

who was born on the island of Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

, (present-day Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

), and lived from about 1475–1546.

Siege of Gibraltar and the Battle of Trafalgar

July 1779 saw the start of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, an attempt by France and Spain to wrest control of Gibraltar from the British. The

July 1779 saw the start of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, an attempt by France and Spain to wrest control of Gibraltar from the British. The garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mili ...

survived all attacks, including an assault on September 13, 1782, that included 48 ships and 450 cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

. In October 1805, the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1 ...

took place, which involved 60 vessels, 27 British, and 33 French and Spanish. The British did not lose a single ship, and destroyed the enemy fleet, but Admiral Lord Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

died in the battle. It was the most significant naval battle of the beginning of the 19th century, and confirmed the British Navy's supremacy of the time.

Lighthouses

The Pharos of

The Pharos of Meloria

Meloria is a rocky skerry, surrounded by a shoal, off the Tuscan coast, in the Ligurian sea, north-west of Livorno.

Meloria shoal

The Meloria shoal is an attractive archaeological, naturalistic and historical region that makes part, since 2010 ...

is often considered the first lighthouse in Europe since Roman times. Meloria, a rocky islet off the Tuscan coast in the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

, was the location of two medieval naval battles. The Tower of Hercules

The Tower of Hercules ( es, Torre de Hércules) is the oldest existent lighthouse known. It has an ancient Roman origin on a peninsula about from the centre of A Coruña, Galicia, in north-western Spain. Until the 20th century, it was known as ...

(Torre de Hércules), in northwestern Spain, is almost 1,900 years old. The ancient Roman lighthouse stands near A Coruña

A Coruña (; es, La Coruña ; historical English: Corunna or The Groyne) is a city and municipality of Galicia, Spain. A Coruña is the most populated city in Galicia and the second most populated municipality in the autonomous community and ...

, Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, and is 57 metres (185 ft) in height. It is the oldest working Roman lighthouse in the world.

According to ''Smithsonian'', a lighthouse on the Gironde River in France, Cardovan Tower, was the first lighthouse to use a Fresnel lens in 1822. The light reportedly could be seen from more than at sea.

Oil spills

There have been several large oil spills off the coasts of Europe since 1967. They include: *''Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

'' — A Coruña, Spain, December 3, 1992

*''Amoco Cadiz

''Amoco Cadiz'' was a VLCC (very large crude carrier) owned by Amoco Transport Corp and transporting crude oil for Shell Oil. Operating under the Liberian flag of convenience, she ran aground on 16 March 1978 on Portsall Rocks, from the coa ...

'' — Brittany, France, March 16, 1978

* — Shetland Islands, January 5, 1993

*''Othello'' — Trälhavet Bay, Sweden, March 20, 1970

*''Prestige

Prestige refers to a good reputation or high esteem; in earlier usage, ''prestige'' meant "showiness". (19th c.)

Prestige may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Films

* ''Prestige'' (film), a 1932 American film directed by Tay Garnet ...

'' — Galicia, Spain, November 13, 2002

* — Cornwall, England, March 18, 1967

* West Cork oil spill — south of Fastnet Rock, Ireland, February 16, 2009

See also

*History of Europe

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first ea ...

*Maritime history

Maritime history is the study of human interaction with and activity at sea. It covers a broad thematic element of history that often uses a global approach, although national and regional histories remain predominant. As an academic subject, it ...

*Naval warfare

Naval warfare is combat in and on the sea, the ocean, or any other battlespace involving a major body of water such as a large lake or wide river. Mankind has fought battles on the sea for more than 3,000 years. Even in the interior of large la ...

*Timeline of maritime migration and exploration

This timeline is an incomplete list of significant events of human migration and exploration by sea. This timeline does not include migration and exploration over land, including migration across land that has subsequently submerged beneath the s ...

References

Further reading

* A Study of 16th Century Western Books on Korea: The Birth of an Image, Myongji University *Pryor, John, ''Maritime History'', University of Sydney, course outline *Villiers, Alan, ''Men Ships and the Sea'', National Geographic Society, 1962, pgs. 62, 70, 132 & 133External links

*National Maritime Museum, London{{DEFAULTSORT:Maritime History Of Europe History of Europe

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...