Maria Nikiforova on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

)

, allegiance =

Born in

Born in  In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

Maria Nikiforova welcomed the outbreak of the

Maria Nikiforova welcomed the outbreak of the

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. But as Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. But as Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets

The Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets (russian: Украинская Народная Республика Советов, translit=Ukrainskaya Narodnaya Respublika Sovjetov) was a short-lived (1917–1918) Soviet republic of the Russian S ...

Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

, branch =

, serviceyears = 1914-1919

, rank = Atamansha

, unit =

, commands =

, battles =

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

* Macedonian front

Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

* Oleksandrivsk uprising

, mawards =

, footnotes =

Maria Hryhorivna Nikiforova ( uk, Марія Григорівна Нікіфорова; 1885–1919) was a Ukrainian anarchist partisan leader that led the Black Guards

Black Guards (russian: Чёрная гвардия, ) were armed groups of workers formed after the February Revolution and before the final Bolshevik suppression of other leftwing groups. They were the main strike force of the anarchists. They ...

during the Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

, becoming widely renowned as an atamansha.

A self-described terrorist from the age of 16, she was imprisoned for her activities in Russia but managed to escape to western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. With the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she took up the defencist line and joined the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

on the Macedonian front before returning to Ukraine with the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of governm ...

.

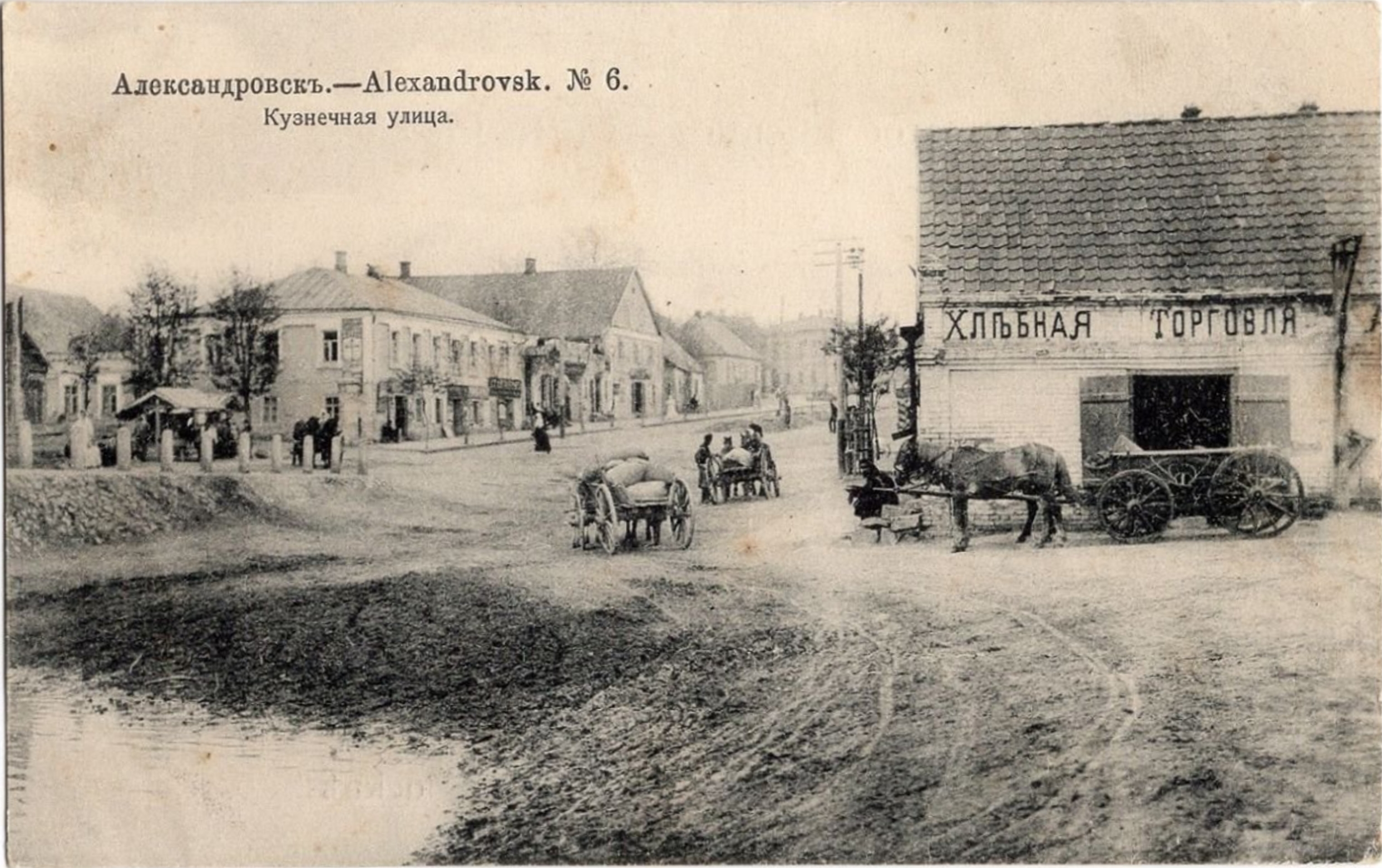

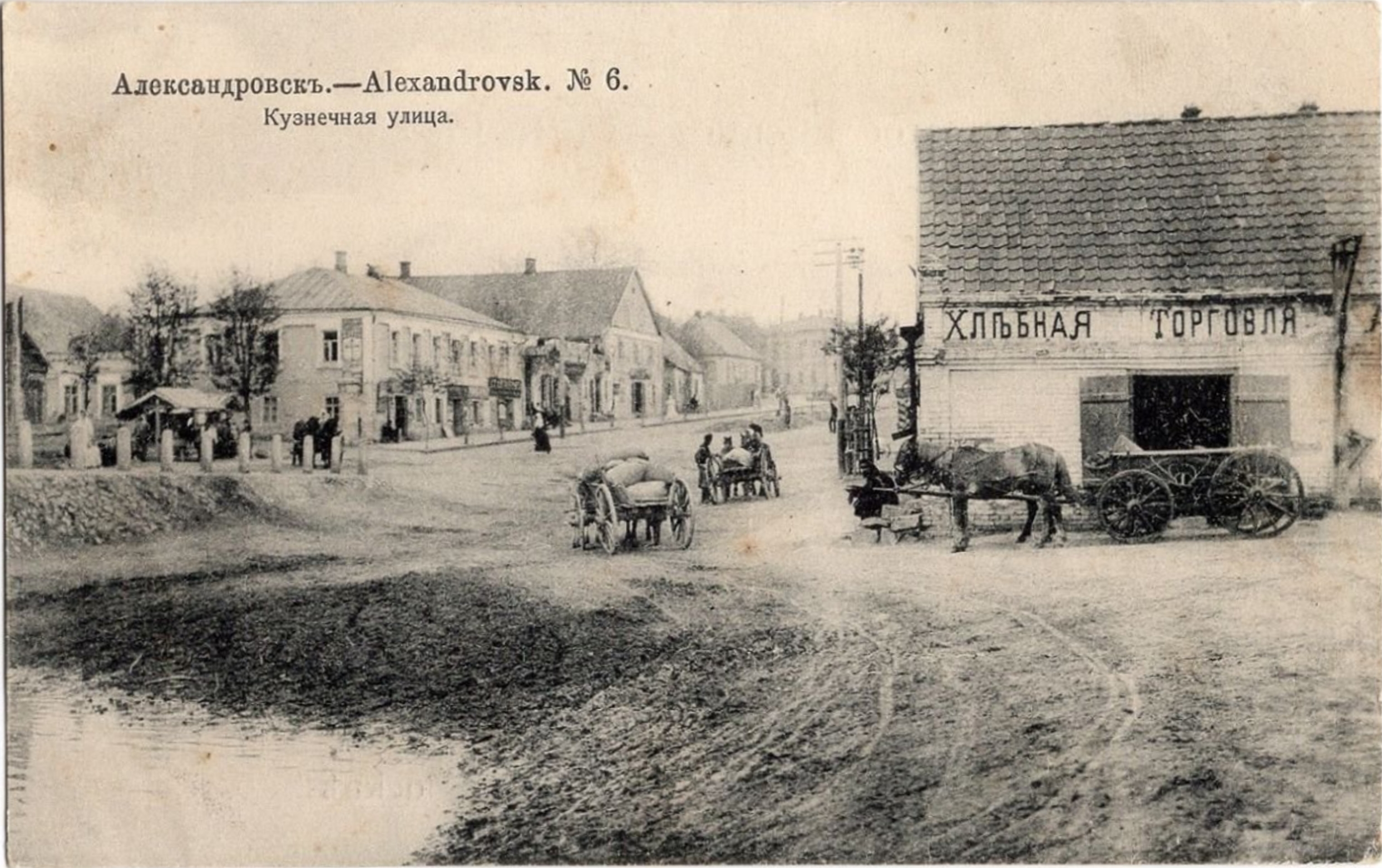

In her home city of Oleksandrivsk

Oleksandrivsk ( uk, Олекса́ндрівськ ) or Aleksandrovsk (russian: Алекса́ндровск ) is a small city in Luhansk Municipality, Luhansk Oblast (region) of Ukraine. Population:

Demographics

Native language as of the Uk ...

, she established an anarchist combat detachment and subsequently attacked the forces of the Russian Provisional Government

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government of the Russian Republic, announced two days before and established immediately ...

and the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

. After the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

escalated into a civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, she joined the side of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Republic (russian: Украинская Советская Республика, translit= Ukrainskaya Sovetskaya Respublika) was one of the earlier Soviet Ukrainian quasi-state formations ( Ukrainian People's Republic of ...

, leading her ''druzhina

In the medieval history of Kievan Rus' and Early Poland, a druzhina, drużyna, or družyna ( Slovak and cz, družina; pl, drużyna; ; , ''druzhýna'' literally a "fellowship") was a retinue in service of a Slavic chieftain, also called ''knyaz ...

'' in capturing Taurida

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' ( gr, Ταυρική or Ταυρικά), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' ( gr, Χερσόνησος Ταυρική, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the ...

and Yelysavethrad from the Ukrainian People's Army

The Ukrainian People's Army ( uk, Армія Української Народної Республіки), also known as the Ukrainian National Army (UNA) or as a derogatory term of Russian and Soviet historiography Petliurovtsy ( uk, Пет� ...

.

When Ukraine was invaded by the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

, she was forced to flee to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, where she was prosecuted for insubordination by the nascent Bolshevik government Under the leadership of Russian communist Vladimir Lenin, the Bolshevik Party seized power in the Russian Republic during a coup known as the October Revolution. Overthrowing the pre-existing Provisional Government, the Bolsheviks established a new ...

. When she returned to Ukraine, she briefly participated in the civilian activities of the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

but before long she had returned to terrorism. She aimed to assassinate the leaders of the White movement (Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

and Alexander Kolchak) but was caught and executed.

Biography

Early life and exile

Born in

Born in Oleksandrivsk

Oleksandrivsk ( uk, Олекса́ндрівськ ) or Aleksandrovsk (russian: Алекса́ндровск ) is a small city in Luhansk Municipality, Luhansk Oblast (region) of Ukraine. Population:

Demographics

Native language as of the Uk ...

in 1885, Maria's father had been an officer during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. At the age of 16, she left home and became a wage labor

Wage labour (also wage labor in American English), usually referred to as paid work, paid employment, or paid labour, refers to the socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer in which the worker sells their labour power under ...

er, working first as babysitter

Babysitting is temporarily caring for a child. Babysitting can be a paid job for all ages; however, it is best known as a temporary activity for early teenagers who are not yet eligible for employment in the general economy. It provides auton ...

, then as a retail clerk

A retail clerk, also known as a salesclerk, shop clerk, retail associate or (in the United Kingdom) shop assistant or customer service assistant, is a service role in a retail business.

A retail clerk obtains or receives merchandise, totals bil ...

, and ultimately as a factory worker, washing bottles in a vodka distillery.

Shortly after starting work, she joined a local anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

group, which had been established in the lead up to the 1905 Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

. Following a period of political probation, Nikiforova became involved in the group's campaign of "motiveless terrorism", during which she staged a number of bombings and expropriation missions, including armed robberies. When Nikiforova was captured, she attempted to commit suicide by blowing herself up, but the bomb failed and she was imprisoned. In 1908, her trial for murder and armed robbery resulted in Nikiforova being sentenced to capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, although this was later commuted to life imprisonment with hard labor, due to her young age. She served part of her sentence in the Petropavlovsk prison in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

before being exiled to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

in 1910.

After staging a prison riot, she escaped via the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, c ...

and subsequently went on to Japan. A group of Chinese anarchists

Anarchism in China was a strong intellectual force in the reform and revolutionary movements in the early 20th century. In the years before and just after the overthrow of the Qing dynasty Chinese anarchists insisted that a true revolution could ...

secured her passage to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, where she briefly stayed with other exiled Russian anarchists

Anarchism in Russia has its roots in the early mutual aid systems of the medieval republics and later in the popular resistance to the Tsarist autocracy and serfdom. Through the history of radicalism during the early 19th-century, anarchism d ...

and published articles in their Russian language newspapers. In 1912, she joined the anarchist movement

The history of anarchism is as ambiguous as anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anar ...

in Restoration Spain

The Restoration ( es, link=no, Restauración), or Bourbon Restoration (Spanish: ''Restauración borbónica''), is the name given to the period that began on 29 December 1874—after a coup d'état by General Arsenio Martínez Campos ended the F ...

and participated in a bank robbery in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

during which she was wounded and forced to clandestinely seek treatment in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

. Herself an intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical bin ...

woman, Nikiforova also reportedly underwent a medical intervention while being treated.

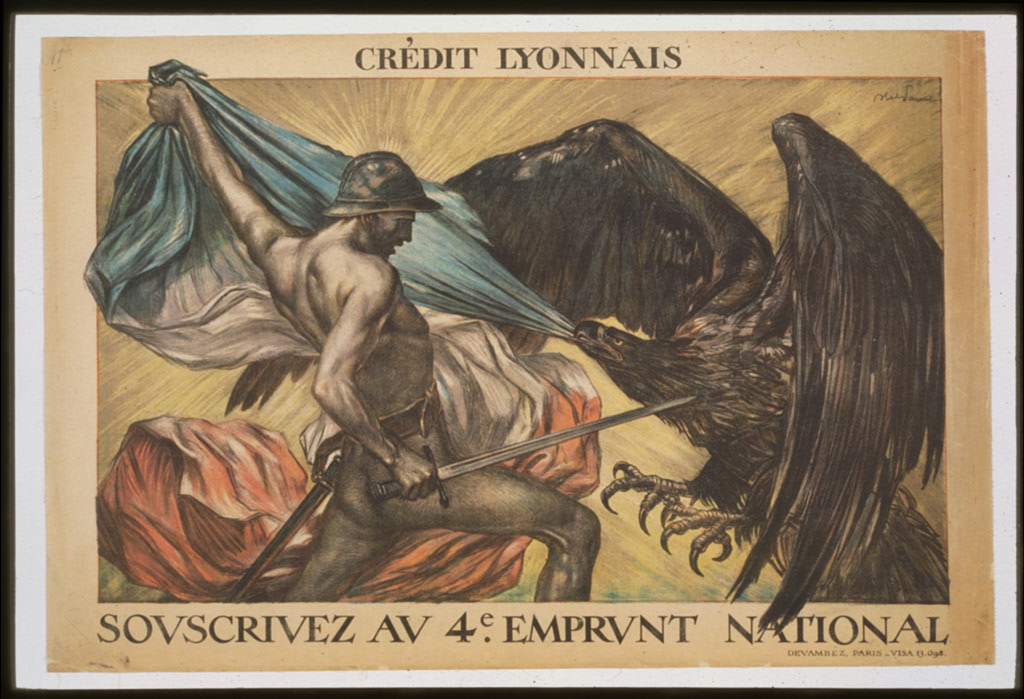

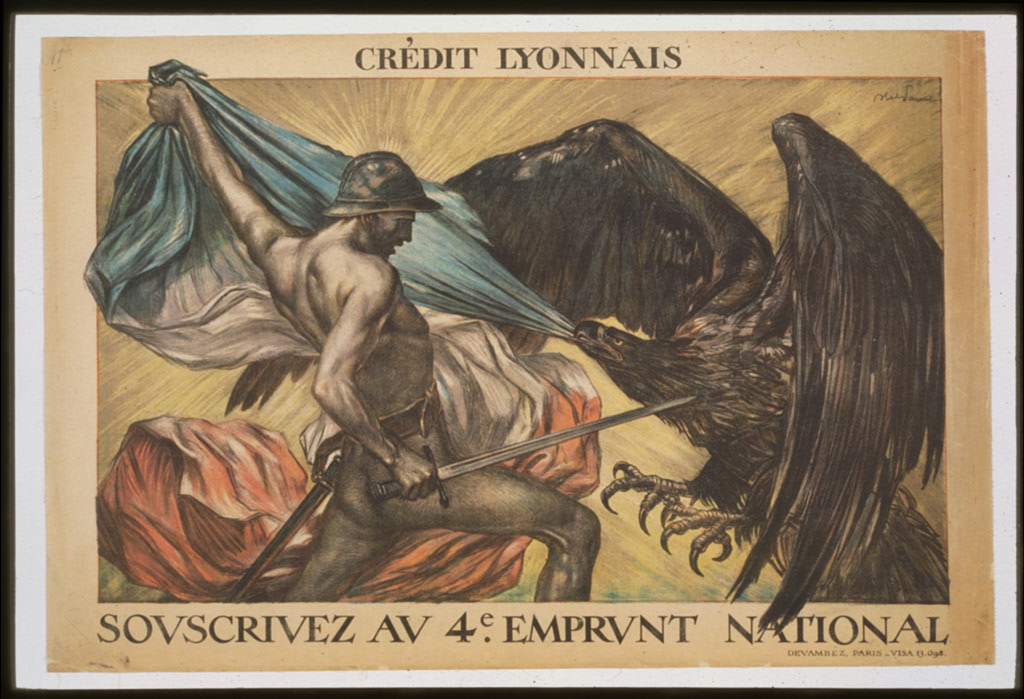

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat

In the cafes of the French capital, Nikiforova met a number of exiled Russian artists and politicians, one of which was the Ukrainian Social-Democrat Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko (russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович Анто́нов-Овсе́енко; ua, Володимир Антонов-Овсєєнко; 9 March 1883 – 10 February 1938), real surna ...

, and even became an artist herself, specializing in painting and sculpting. During this time, she also entered into a marriage of convenience with a Polish anarchist named Witold Brozstek, retaining her last name. Towards the end of 1913, she attended an anarchist conference in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, signing her name as "Marusya", a Slavic diminutive form

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A (abbreviated ) is a word-formati ...

of "Maria". With the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, she sided with Peter Kropotkin's anti-German position, in favor of the Allied powers. She joined up with the French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (french: Légion étrangère) is a corps of the French Army which comprises several specialties: infantry, Armoured Cavalry Arm, cavalry, Military engineering, engineers, Airborne forces, airborne troops. It was created ...

and subsequently graduated as an officer from a military college

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally provides education in a military environment, the exact definition depending on the country concerned. ...

. Nikiforova served on the Macedonian front before the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of governm ...

convinced her to quit the front and return home.

Return to Oleksandrivsk

When Nikiforova arrived in Petrograd, she found the city in a situation of " dual power", with both theProvisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

and the local soviet vying for control while the anarchists mostly acted as shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tra ...

of anti-government unrest. Nikiforova organized and spoke at pro-anarchist rallies in Kronstadt

Kronstadt (russian: Кроншта́дт, Kronshtadt ), also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt or Kronštádt (from german: link=no, Krone for " crown" and ''Stadt'' for "city") is a Russian port city in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city ...

, where she convinced thousands of sailors to participate in an uprising against the Provisional Government, although the lack of Bolshevik support ultimately led to its suppression. Nikiforova narrowly escaped the subsequent government crackdown in Petrograd and fled back to her home city of Oleksandrivsk, finally arriving in July 1917 after eight years in exile. Shortly after arrival, together with the city's 300-strong Anarchist Federation and supported by local factory workers, Nikiforova carried out the expropriation of the local distillery, donating part of the seized money to the local soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

. She soon established a 60-strong anarchist combat detachment and started accumulating armaments procured from attacks on police stations and warehouses, with which she hunted down and executed many of the city's army officers and landlords.

On 29 August 1917, she met with the peasant leader Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

in the anarchist-controlled town of Huliaipole

Huliaipole ( uk, Гуляйполе ; ) is a city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine. It is known as the birthplace of Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno. In 2021, it had a population of Huliaipole was attacked by Russian ...

, where she gave a speech advocating for an insurrection

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against the rule of the newly-established Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Council of Ukraine ( uk, Українська Центральна Рада, ) (also called the Tsentralna Rada or the Central Rada) was the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputie ...

, warning of a potential counter-revolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

. Partway through Nikiforova's speech, the anarchists received news from Petrograd of an attempted coup by Lavr Kornilov and resolved to form a Committee for the Defence of the Revolution (CDR). The CDR began making plans to seize weapons from the local bourgeoisie but Nikiforova countered with a plan of her own: to raid the nearby garrison at Orikhiv

Orikhiv ( uk, Орі́хів, ) is a city in Polohy Raion, Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine. As of January 2022 its population was approximately

History

Orikhiv was founded in about 1783 near the Konka River; it was incorporated in 1801. It is si ...

. By 10 September, she had pulled together 200 fighters, armed only with only a few dozen weapons, and set out for Orikhiv by train. Upon arrival, the anarchist detachment surrounded and captured the Russian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �ВSukhoputnyye voyska V}), also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Force ...

regiments. Nikiforova ordered the execution of all officers and disarmed the rank-and-file soldiers before letting them return to their homes. She delivered the captured weapons back to the CDR in Huliaipole, then returned to Oleksandrivsk herself.

Huliaipole subsequently began to receive threats from the local organ of the Provisional Government in Oleksandrivsk, which was disturbed by the rising anarchist influence in the region. Makhno responded by traveling to the city with Nikiforova as a guide and speaking directly to the local workers' organizations. After Makhno left the city, the authorities swiftly arrested and imprisoned Nikiforova. News of her arrest quickly spread; a delegation of workers demanded her release the next day. After being rebuffed by the Provisional Government, the workers forcibly brought the leader of the soviet to the prison and secured her release, following which Nikiforova gave a speech to the crowd, calling for anarchy. Anarchists from Huliaipole, who had been dispatched to attack Oleksandrivsk and force Nikiforova's release, celebrated upon hearing that their work had already been carried out.

During the subsequent election to the Oleksandrivsk soviet, the composition of the new body was distinctly more left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

and included a number of anarchist delegates.

Battle for Oleksandrivsk

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

as another step towards the "withering away of the state

Withering away of the state is a Marxist concept coined by Friedrich Engels referring to the idea that, with the realization of socialism, the state will eventually become obsolete and cease to exist as society will be able to govern itself without ...

". She set about establishing armed detachments known as the "Black Guards

Black Guards (russian: Чёрная гвардия, ) were armed groups of workers formed after the February Revolution and before the final Bolshevik suppression of other leftwing groups. They were the main strike force of the anarchists. They ...

" in Oleksandrivsk, preparing an organized anarchist response for a conflict that was rapidly escalating into civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. In November 1917, the Oleksandrivsk Soviet voted 147 to 95 in favor of joining the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

and refused to recognize the authority of the newly-proclaimed Russian Soviet Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

. Nikiforova responded by allying with the local revolutionary socialists

The Revolutionary Socialists ( ar, الاشتراكيون الثوريون; ) (RS) are a Trotskyist organisation in Egypt originating in the tradition of 'Socialism from Below'. Leading RS members include sociologist Sameh Naguib. The organisatio ...

, securing a clandestine shipment of weaponry and the support of the local detachment of the Black Sea Fleet. On 12 December, they launched their uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

, managing to overthrow the Soviet and reconstitute it with delegates from the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, Left SRs

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (russian: Партия левых социалистов-революционеров-интернационалистов) was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Revo ...

and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

.

On 25 December, Nikiforova and her detachment went to Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets

The Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets (russian: Украинская Народная Республика Советов, translit=Ukrainskaya Narodnaya Respublika Sovjetov) was a short-lived (1917–1918) Soviet republic of the Russian S ...

while also expropriating goods from the local shops and redistributing them to the population. A few days later, she led Black Guards into battle against the haydamak

The haidamakas, also haidamaky or haidamaks (singular ''haidamaka'', ua, Гайдамаки, ''Haidamaky'') were Ukrainian paramilitary outfits composed of commoners (peasants, craftsmen), and impoverished noblemen in the eastern part of the ...

s at Katerynoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

, capturing the city for the Soviets and personally disarming 48 soldiers. Civil war became an inevitability following the dissolution of the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, as the Bolsheviks began to look towards the anarchists around Nikiforova as a necessary base of support in Ukraine. While she had been away, her home city of Oleksandrivsk had fallen again under the control of the Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Council of Ukraine ( uk, Українська Центральна Рада, ) (also called the Tsentralna Rada or the Central Rada) was the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputie ...

after three days of fighting, forcing the local anarchist detachments to withdraw. On 2 January 1918, the city was again recaptured after the arrival of Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard lead ...

from Russia and Black Guards from Huliaipole, forcing the haydamaks in turn to retreat to right-bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine ( uk , Правобережна Україна, ''Pravoberezhna Ukrayina''; russian: Правобережная Украина, ''Pravoberezhnaya Ukraina''; pl, Prawobrzeżna Ukraina, sk, Pravobrežná Ukrajina, hu, Jobb p ...

. Two days later, a revolutionary committee (Revkom) was constituted as the center of soviet power in Oleksandrivsk. Nikiforova was elected as its deputy leader.

Although the haymadaks had fled, Cossacks were beginning to return from the external front in order to join up with Alexey Kaledin

Aleksei Maksimovich Kaledin (russian: Алексе́й Макси́мович Каледи́н; 24 October 1861 – 11 February 1918) was a Don Cossack Cavalry General who led the Don Cossack White movement in the opening stages of the Russian ...

's Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, and Oleksandrivsk was in the path towards their home regions of the Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

and Kuban. With the Black Guards scrambling to rally their defenses, a failed assault by the first wave of Cossacks ended in their disarmament by the Revkom. While the disarmament took place, the city politicians' speeches, attempting to rally the Cossacks to the cause of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

, were largely ignored and even mocked. But when Nikiforova spoke, calling on the "butchers of the Russian workers" to renounce the old ways of Tsarism, many of the Cossacks began to display humility; some openly wept and others maintained contact with the local anarchists. When the Cossacks departed, Makhno and Nikiforova returned to their duties in the Revkom. But after a dispute between the two regarding the sentencing of the prosecutor that had overseen Makhno's own imprisonment, Makhno decided to renounce his position and return to Huliaipole, leaving Nikiforova in place as the sole commander of Oleksandrivsk's Black Guards.

The Free Combat Druzhina

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. But as Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief,

In a joint operation together with the Huliaipole anarchists, Nikiforova launched another raid against the garrison in Orikhiv, seizing a cache of arms and sending them on to Huliaipole, rather than handing them over to her nominal commander Semyon Bogdanov. But as Nikiforova's Black Guards had helped to establish Soviet power in the eastern Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv, Katerynoslav and Oleksandrivsk, she enjoyed the unqualified support of the Ukrainian Soviet commander-in-chief, Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko (russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович Анто́нов-Овсе́енко; ua, Володимир Антонов-Овсєєнко; 9 March 1883 – 10 February 1938), real surna ...

, who gave her funds to upgrade her detachment, which became known as the .

Reinforced by extra troops, the Druzhina was supplied with artillery cannons, armored cars, tachanka

A tachanka ( ukr, тачанка, rus, тача́нка, pl, taczanka) was a horse-drawn machine gun, usually a cart (such as charabanc) or an open wagon with a heavy machine gun installed in the back. A tachanka ...

s, warhorses and even an armored train, which they decorated with a number of anarchist flags, leaving them better-equipped than even the units of the Red Guards. The militants of the Druzhina also largely rejected uniform

A uniform is a variety of clothing worn by members of an organization while participating in that organization's activity. Modern uniforms are most often worn by armed forces and paramilitary organizations such as police, emergency services, ...

, in favor of their own individual senses of fashion

Fashion is a form of self-expression and autonomy at a particular period and place and in a specific context, of clothing, footwear, lifestyle, accessories, makeup, hairstyle, and body posture. The term implies a look defined by the fashion i ...

. While the core of the group was personally loyal to Nikiforova, including a number of experienced veterans of the Black Sea Fleet, the larger section around them participated in the unit on a more ephemeral basis.

Travelling in echelon formation

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

s, which the Left SR politician Isaac Steinberg

Isaac Nachman Steinberg (russian: Исаак Нахман Штейнберг; 13 July 1888 – 2 January 1957) was a lawyer, Socialist Revolutionary, politician, a leader of the Jewish Territorialist movement and writer in Soviet Russia and in ex ...

compared to the mythical Flying Dutchman

The ''Flying Dutchman'' ( nl, De Vliegende Hollander) is a legendary ghost ship, allegedly never able to make port, but doomed to sail the seven seas forever. The myth is likely to have originated from the 17th-century Golden Age of the Du ...

, the Druzhina advanced against the forces of the White movement and the Ukrainian nationalists

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

. The Druzhina pushed as far as Crimea, where they captured Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

, sacked Livadia Palace

Livadia Palace (russian: Ливадийский дворец, uk, Лівадійський палац) is a former summer retreat of the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II, and his family in Livadiya, Crimea. The Yalta Conference was held there i ...

and liberated anarchist political prisoners in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

. Having participated in the establishment of the Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic, Nikiforova was elected to head the Peasant Soviet in Feodosia

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

and used her new position to establish more detachments of the Black Guards.

Battle for Yelysavethrad

The Druzhina then moved on to the central Ukrainian city of Yelysavethrad, bloodlessly capturing the city from the Ukrainian nationalists and establishing a revolutionary committee to oversee its transition to Soviet power. While occupying the city, she assassinated a Russian officer, expropriated local stores and redistributed basic necessities to the population, and established abarter

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists disti ...

economy for non-essential goods, all in open defiance the Bolshevik-controlled Revkom. Nikiforova accused the Revkom of being too tolerant towards the bourgeoisie and having constituted a new ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by exte ...

, even threatening to disperse the organ and shoot its chairman, due to her opposition to all forms of government. The Revkom responded by ordering her to leave the city, which she did a few days later, but only after looting the city's military college of all their weapons, leaving behind a newly-established local detachment of Black Guards.

The Central Council of Ukraine responded to the rapid Soviet advance by signing a treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

with the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

. With the support of the Ukrainian haydamaks, the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

and Imperial German Army launched an invasion of Ukraine, pushing the Soviet lines back again. When the German forces arrived at Yelysavethrad, the Revkom immediately evacuated, leaving a power vacuum in the city. While the occupying powers attempted to recruit men to its side, even conscripting the local peasantry into service, the Druzhina returned to occupy Yelysavethrad, taking over the local railway station and regularly touring the city to expropriate money from the bourgeoisie. After days of tense peace between the city's official government and the anarchists, a conflict broke out between the anarchists and local factory workers, giving the government forces an opportunity to move against the Druzhina. Although the anarchists managed to defend themselves against the assault, they were far outnumbered, forcing them to withdraw to Kanatovo, where they discovered that a number of their soldiers had been taken prisoner.

Red Guards led by attempted to retake the city, but they were surrounded and wiped out within hours of arrival, prompting the city authorities to beginning executing their prisoners of war. Nikiforova subsequently led the Druzhina in an assault by rail, digging in at the suburbs, where they were met by thousands of well-armed troops, who began spreading rumours to the local population that depicted Nikiforova as a sacrilegious bandit leader. The battle descended into a war of attrition, with constant artillery and machine gun fire exchanged between the trenches over the course of two days. On 26 February, the Druzhina was reinforced by a detachment of Red Guards from , but these troops were largely ineffective against the city's defenses. Under heavy bombardment, the Druzhina fell back to Znamianka, where they were reinforced by more Red Guards under the command of Mikhail Muravyov, fresh from their victory in the Battle of Kyiv. Although the city's authorities had requested reinforcements from the Central Powers, none arrived, leaving the city vulnerable to a Soviet assault. While the Ukrainian nationalists held off Nikiforova's advance from the north, led an assault against the largely undefended south, forcing the city to capitulate. The city's authorities complied with the Soviet demands and released Nikiforova's imprisoned soldiers, with the city ultimately remaining in Soviet hands until 19 March, when an Imperial German assault forced the Soviet forces to evacuate.

Retreat

The forces of theUkrainian Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Republic (russian: Украинская Советская Республика, translit= Ukrainskaya Sovetskaya Respublika) was one of the earlier Soviet Ukrainian quasi-state formations ( Ukrainian People's Republic of ...

were ultimately unable to withstand the combined assault of the Central Powers, with only sporadic resistance delaying the offensive. After leaving Yelysavethrad, the Druzhina stooped in Berezivka, where they came into conflict with another anarchist detachment led by Grigory Kotovsky

Grigory Ivanovich Kotovsky (russian: Григо́рий Ива́нович Кото́вский, ro, Grigore Kotovski; – August 6, 1925) was a Soviet military and political activist, and participant in the Russian Civil War. He made a career ...

, after Nikiforova had attempted to extort money from the town's inhabitants. The Druzhina subsequently abandoned their train and reformed as a cavalry detachment, arranging their horses by fur colour, with Nikiforova herself riding at the head on a white horse.

The Druzhina rendezvoused with other Soviet forces at , finding the local estate in the hands of the Bolshevik commander . Nikiforova immediately set about seizing the estate's goods and redistributing them to the local population, to the annoyance of Matveyev, who she was still formally subordinated to. Matveyev resolved to disarm the Druzhina before any more anarchists arrived at the rendezvous. He called a general meeting in which the principles of unity and discipline were to be discussed, but when Bolsheviks started making complaints about the anarchists, Nikiforova immediately understood the true purpose of the meeting and signalled her partisans to leave, escaping the village on horseback before they could be disarmed.

The Druzhina subsequently moved towards Oleksandrivsk, hoping to defend it from the Central Powers, but upon arrival found the city's Red Guards were already organizing their retreat. On 13 April, the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen

Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (german: Ukrainische Sitschower Schützen; uk, Українські cічові стрільці (УСС), translit=Ukraïnski sichovi stril’tsi (USS)) was a Ukrainian unit within the Austro-Hungarian Army d ...

were able to capture the city, finding the dead body of a woman that they mistakenly believed to be Nikiforova. On 18 April, they were followed by the Imperial German Army, which forced out the remaining Soviet forces, with the Druzhina being one of the last Soviet detachments to leave. They subsequently linked up with Nestor Makhno's forces in Tsarekostyantynivka, where they found out that Huliaipole had also fallen to the Ukrainian nationalists. Nikiforova proposed a mission to rescue captured members of the town's revolutionary committee, but after a number of Red commanders refused to join and news came in of the continued German advance, she abandoned the plan and continued to retreat east.

Trials

Following the Soviet defeat in Ukraine, the Bolsheviks no longer saw the use in their anarchist allies and repressions against the Russian anarchist movement began to be carried out by the Cheka. Upon Nikiforova's arrival inTaganrog

Taganrog ( rus, Таганрог, p=təɡɐnˈrok) is a port city in Rostov Oblast, Russia, on the north shore of the Taganrog Bay in the Sea of Azov, several kilometers west of the mouth of the Don River. Population:

History of Taganrog

Th ...

, she was immediately arrested on charges of looting and desertion, while the Druzhina was finally disarmed, in an operation overseen by the Ukrainian Bolshevik leader Volodymyr Zatonsky

Volodymyr Petrovych Zatonsky ( uk, Володи́мир Зато́нський, russian: Влади́мир Петро́вич Зато́нский ''Vladimir Petrovich Zatonsky''; July 27, 1888 – July 29, 1938) was a Soviet politician, aca ...

. The local anarchists and Left SRs demanded an explanation for Nikiforova's arrest, with Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko himself sending a telegram in support of the anarchists, while further arrivals of Ukrainian anarchists to the city began to make the situation untenable. In April 1918, a revolutionary tribunal

The Revolutionary Tribunal (french: Tribunal révolutionnaire; unofficially Popular Tribunal) was a court instituted by the National Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders. It eventually became one of the ...

was held by the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. With witnesses both for the prosecution and the defense in attendance, Nikiforova was confident that revolutionary justice would be upheld and she was ultimately acquitted on all charges.

The anarchists in Taganrog subsequently held a conference about the situation in Ukraine, during which Makhno and the Huliaipole anarchists decided they would return to southern Ukraine and carry out a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the Central Powers. Other anarchists joined Nikiforova's Druzhina, but the continued German offensive forced them to retreat to Rostov-on-Don, where they looted the local banks and burned all the bonds, deeds and loan agreement

A loan agreement is a contract between a borrower and a lender which regulates the mutual promises made by each party. There are many types of loan agreements, including "facilities agreements," "revolvers," " term loans," "working capital loans." ...

s they found in a public bonfire. Here too, Nikiforova noticed that the Bolsheviks were closing in on them and decided to take the Druzhina north towards Voronezh

Voronezh ( rus, links=no, Воро́неж, p=vɐˈronʲɪʂ}) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on ...

, and over the following months they moved between a number of towns along the Ukrainian border. After the defeat of the Central Powers forced them to withdraw from Ukraine, the Ukrainian State

The Ukrainian State ( uk, Українська Держава, translit=Ukrainska Derzhava), sometimes also called the Second Hetmanate ( uk, Другий Гетьманат, translit=Druhyi Hetmanat, link=no), was an anti-Bolshevik government ...

was overthrown by the Directorate of Ukraine

The Directorate, or Directory () was a provisional collegiate revolutionary state committee of the Ukrainian People's Republic, initially formed on November 13–14, 1918 during a session of the Ukrainian National Union in rebellion against Sk ...

under Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian Peop ...

, making room for the Druzhina to finally return to the country in late 1918. In the subsequent power struggle, the Druzhina managed to seize Odesa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrati ...

from the White movement, demolishing the prison before an armed intervention by the Allied Powers forced them to quit the city.

The Druzhina then moved on to Saratov, where it was again disarmed and Nikiforova herself was again arrested. But the Cheka were reluctant to execute her without trial and had her transferred to Moscow, where she was briefly held in Butyrka prison

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia it ...

. She was released on bail, posted by Apollon Karelin

Apollon Andreyevich Karelin ( Russian: Аполло́н Андре́евич Каре́лин; January 23, 1863, St. Petersburg - March 20, 1926, Moscow) was a Russian anarchist.

Born into a wealthy family, Karelin became radicalized in his y ...

and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, and she was reunited with her husband, who had taken a job in the new Soviet government. After a spell of working for the artistic institution Proletkult

Proletkult ( rus, Пролетку́льт, p=prəlʲɪtˈkulʲt), a portmanteau of the Russian words "proletarskaya kultura" (proletarian culture), was an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revolu ...

, Nikiforova's trial by revolutionary tribunal began on 21 January 1919. She was presented with the same charges that the Taganrog tribunal had already acquitted her of, with Georgy Pyatakov

Georgy (Yury) Leonidovich Pyatakov (russian: Гео́ргий Леони́дович Пятако́в; 6 August 1890 – 30 January 1937) was a leader of the Bolsheviks and a key Soviet politician during and after the 1917 Russian Revolution ...

accusing her again of looting and desertion. On 25 January, ''Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' announced that she had been found guilty of insubordination, although she had again been acquitted on the charges of looting, and that her punishment was a ban on holding any public office for six months.

Activities in Huliaipole

Almost immediately following the trial, Nikiforova set out for Huliaipole, now the center of an autonomous anarchist republic known as theMakhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

, as part of an agreement between Nestor Makhno's Revolutionary Insurgent Army and the Ukrainian Bolsheviks. Upon her arrival, Makhno had Nikiforova put in charge of the anarchists' hospitals, nurseries and schools, forbidding her from participating in military activities due to the terms of her sentence. Nikiforova's anti-Bolshevik attitude became an immediate problem for the Makhnovists, who were more focused on fighting the White movement, with Makhno himself physically removing her from a stage after she publicly denounced the Bolsheviks during a Regional Congress. When she briefly returned to Oleksandrivsk, any anarchists she met or stayed with were promptly arrested by the Cheka.

During the spring of 1919, Huliaipole was visited several times by a series of high-ranking Bolsheviks, during which Nikiforova acted as a hostess. Antonov-Ovseenko recalled meeting his "old acquaintance" on 28 April, while reviewing Makhno's troops and the city of Huliaipole. Seeking to clarify rumors of corruption and counter-revolutionary activity among Makhno's ranks and the soviet of the city, Antonov-Ovseenko wrote glowingly of his impression of Huliaipole. But Antonov-Ovseenko's attempts to lobby for military support for the anarchists faltered and his political power declined. Within weeks of his visit, he was replaced as commander-in-chief by Jukums Vācietis

Jukums Vācietis (russian: Иоаким Иоакимович Вацетис, link=no, ''Ioakim Ioakimovich Vatsetis''; 11 November 1873 – 28 July 1938) was a Latvian Soviet military commander. He was a rare example of a notable Soviet leader ...

.

Nevertheless, Antonov-Ovseenko's reports quickly attracted Lev Kamenev to himself visit Huliaipole the very next week. Nikiforova met Kamenev and his entourage at the train station, and offered to escort them into the city. After meeting Makhno and touring the city, Kamenev was impressed with Nikiforova, and upon returning to Katerynoslav

Dnipro, previously called Dnipropetrovsk from 1926 until May 2016, is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper Rive ...

, he telegraphed Moscow officials with an order that her sentence be reduced to half of its original term.

Capture and death

Following news of the reduction of her sentence, Nikiforova moved toBerdiansk

Berdiansk or Berdyansk ( uk, Бердя́нськ, translit=Berdiansk, ; russian: Бердя́нск, translit=Berdyansk ) is a port city in the Zaporizhzhia Oblast (province) in south-eastern Ukraine. It is on the northern coast of the Sea of ...

and began work on establishing a new detachment of Black Guards, bringing together a number of former Makhnovists and anarchist refugees, including her husband Witold Brzostek. But by June 1919, the Makhnovshchina

The Makhnovshchina () was an attempt to form a stateless anarchist society in parts of Ukraine during the Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It existed from 1918 to 1921, during which time free soviets and libertarian communes operated un ...

had been outlawed by the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

and the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

had launched an offensive against the Makhnovist rear, forcing the Ukrainian anarchists to regroup. While Makhno moved towards consolidating his military force, Nikiforova returned to her old ways, deciding to carry out a campaign of terrorism against all enemies of the Ukrainian anarchists. When the pair reunited at Tokmak Tokmak may refer to one of the following:

* Tokmak, Ukraine, a city in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Ukraine

*Tokmak, Uzbekistan, a city in Uzbekistan

*Tokmok, a city in Kyrgyzstan, often also spelt Tokmak

*Molochna

The Molochna (, russian: Моло́чн ...

, Nikiforova asked Makhno for money to fund her terrorist campaign. The meeting quickly devolved into a Mexican standoff as the two drew guns on each other, but Makhno ultimately decided to give her some of the insurgent army's funds.

Nikiforova subsequently split up her detachment into three and dispatched them to different fronts. She sent one group to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

, where they were ordered to assassinate Alexander Kolchak, the Supreme Ruler of the Russian State

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

* Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and pe ...

, but they were ultimately unable to locate him and instead decided to join the anti-White partisans. The other group went to Kharkiv

Kharkiv ( uk, wikt:Харків, Ха́рків, ), also known as Kharkov (russian: Харькoв, ), is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Ukraine.Cheka, but by the time they arrived the city had been evacuated and the prisoners had been shot. They decided to move on to

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, where they carried out a series of armed robberies to fund their planned operation to assassinate the Bolshevik Party leadership. On 25 September 1919, they managed to kill 12 and wound 55 other leading Bolsheviks in a bomb attack on a party meeting. The group was eventually wiped out during shoot outs with the Cheka, with the last remaining members blowing themselves up after being surrounded in a dacha.

Nikiforova and Brzostek themselves led the third group to Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, the headquarters of South Russia, where they planned to assassinate the White commander-in-chief Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (russian: Анто́н Ива́нович Дени́кин, link= ; 16 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New St ...

. However, on 11 August, the couple were recognized in Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

and arrested, forcing the rest of the group to quit Crimea and flee to the Kuban People's Republic

The Kuban People's Republic (KPR), or Kuban National Republic (KNR), (russian: Кубанская Народная Республика, Kubanskaya Narodnaya Respublika; uk, Кубанська Народна Республiка, Kubanska Narodn ...

, where they joined the region's anti-White partisans. After spending a month gathering evidence, on 16 September, Nikiforova and Brzostek were court-martialed by , the Governor of Sevastopol. Nikiforova was charged with having executed counter-revolutionaries, including White officers and the bourgeoisie, while Brzostek was charged simply with having been her husband during these events. Throughout the trial, Nikiforova displayed persistent contempt of court, swearing at the tribunal as her sentence was read. The couple were both found guilty and sentenced to execution by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are u ...

, with Nikiforova finally breaking down into tears as she said goodbye to her husband, before they were both shot.

On 20 September, the ''Oleksandrivsk Telegraph'' reported on Nikiforova's death, celebrating it as a victory for the White movement. Only two weeks later, the city was recaptured by the Makhnovshchina, definitively ending the White movement's control over southern Ukraine.

Political positions

Anarchism and revolution

In her youth, Nikiforova enteredanarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

politics and adopted militant tactics to pursue them. Throughout her years of activism, Nikiforova gave numerous speeches espousing her political opinions. However, transcriptions and quotes from her speeches scarcely survived the Soviet era, and she was not known to write her views in letters, essays, or articles. What is known of her speeches is that she was widely regarded for her charismatic oratory, which she used to expound anarchist views. Widely known as an anarchist, she was said to constantly wear entirely black clothing as a symbol of her libertarian philosophy.

During times of revolution, she favored immediate and complete redistribution of property owned by wealthy land owners, declaring, "The workers and peasants must, as quickly as possible, seize everything that was created by them over many centuries and use it for their own interests."

However, while she constantly spoke in favor of anarchist philosophy, she warned against vanguardism

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form orga ...

and elitism, insisting that anarchists could not guarantee positive social change. "The anarchists are not promising anything to anyone." She cautioned, "The anarchists only want people to be conscious of their own situation and seize freedom for themselves."

Conflicts with Soviet authority

Upon returning to Russia in 1917, Nikiforova was influenced byApollon Karelin

Apollon Andreyevich Karelin ( Russian: Аполло́н Андре́евич Каре́лин; January 23, 1863, St. Petersburg - March 20, 1926, Moscow) was a Russian anarchist.

Born into a wealthy family, Karelin became radicalized in his y ...

, a veteran anarchist who advocated a tactical strategy of "Soviet anarchism." Meeting her in Petrograd, Karelin's political tactics encouraged anarchist participation in Soviet institutions with the long term plan of directing them towards an anarchist agenda, provided these institutions did not deviate from revolutionary goals. In the event that they deviated from a radical agenda, anarchists were to rebel against them. Such institutional cooperation was widely disliked among anarchists, as they were largely a minority within such institutions, rendering their activity ineffectual.

Nikiforova agreed to ally with the Bolsheviks under special circumstances and negotiated to have herself appointed to a soviet institution, briefly becoming the Deputy leader of the Oleksandrivsk revkom {{no footnotes, date=May 2016A revolutionary committee or revkom (russian: Революционный комитет, ревком) were Bolshevik-led organizations in Soviet Russia and other Soviet republics established to serve as provisional gove ...

. She would go on to help establish footholds for Soviet power in several Ukrainian cities, demanding material support from Bolshevik agents in return, which she then used to pursue her anarchist agenda. Although she would ally herself with the Red Army on multiple occasions, she was constantly at odds with their commanders and personally antagonized several, arguing against some their practices on revolutionary grounds. Upon discovering that a Soviet commander was hoarding luxury goods looted from an aristocrat's home, she angrily confronted him for his selfishness. "The property of the estate owners doesn't belong to any particular detachment," she declared "but to the people as a whole. Let the people take what they want."

Legacy

Postmortem mythology

Rumours about her alleged survival persisted after Nikiforova's death and her legacy created an opportunity for copycats, with three women fighters adopting the name of "Marusya" as apseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

throughout the remainder of the Ukrainian War of Independence

The Ukrainian War of Independence was a series of conflicts involving many adversaries that lasted from 1917 to 1921 and resulted in the establishment and development of a Ukrainian republic, most of which was later absorbed into the Soviet U ...

. In 1919, a 25-year-old Ukrainian nationalist school teacher adopted the name Marusya Sokolovskaia and took command her late brother's cavalry detachment, before she was captured by the Reds and shot. In 1920-1921, Marusya Chernaya ( en, Black Maria) was also commander of a cavalry regiment in the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine

The Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine ( uk, Революційна Повстанська Армія України), also known as the Black Army or as Makhnovtsi ( uk, Махновці), named after their leader Nestor Makhno, was a ...

, before dying in battle against the Red Army. During the Tambov Rebellion

The Tambov Rebellion of 1920–1921 was one of the largest and best-organized peasant rebellions challenging the Bolshevik government during the Russian Civil War. The uprising took place in the territories of the modern Tambov Oblast and part ...

in Russia, one of the rebel commanders was a woman named Marusya Kosova, who disappeared after the suppression of the revolt.

In the years following her death, Nikiforova was also rumoured to have become a Soviet spy in Paris, where she was alleged to have been involved in the assassination of the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura

Symon Vasylyovych Petliura ( uk, Си́мон Васи́льович Петлю́ра; – May 25, 1926) was a Ukrainian politician and journalist. He became the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian Army and the President of the Ukrainian Peop ...

. Although the actual identity of the assassin was the Ukrainian Jewish anarchist Sholom Schwartzbard

Samuel "Sholem" Schwarzbard (russian: Самуил Исаакович Шварцбурд, ''Samuil Isaakovich Shvartsburd'', yi, שלום שװאַרצבאָרד, french: Samuel 'Sholem' Schwarzbard; 18 August 1886 – 3 March 1938) was a Jewis ...

.

Historiography

Nikiforova's illicit activities meant that she left very few records during her life, only emerging as a public figure during her final years as a military commander. Available accounts of her life have either come from her military service record or from the memoirs of her contemporaries, such asNestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

and Viktor Bilash

Viktor Fedorovych Bilash ( uk, Віктор Федорович Білаш; 1893 – 24 January 1938) was the Chief of Staff of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine (RIAU) under Nestor Makhno. A gifted military commander, Bilash himself pl ...

.

Nikiforova's biography was largely neglected by Soviet historiography

Soviet historiography is the methodology of history studies by historians in the Soviet Union (USSR). In the USSR, the study of history was marked by restrictions imposed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Soviet historiography i ...

, which focused its women's history

Women's history is the study of the role that women have played in history and the methods required to do so. It includes the study of the history of the growth of woman's rights throughout recorded history, personal achievement over a period of ...

largely on female Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, only ever referencing Nikiforova briefly and using negative depictions. She has likewise been largely neglected in Ukrainian historiography

Prehistoric Ukraine, as a part of the Pontic steppe in Eastern Europe, played an important role in Eurasian cultural contacts, including the spread of the Chalcolithic, the Bronze Age, Indo-European migrations and the domestication of the hors ...

, as her staunch anti-nationalist positions directly contradicted the historical narratives of Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

, as well as anarchist historiography, which has focused most of its attention on Nestor Makhno. Nevertheless, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, there has been a renewed interest in Nikiforova, with several essays and a biography about her life being published during the 21st century.

See also

;Lists * List of guerrillas *List of military commanders

This is a list of ''lists of military commanders''.

Asia Philippines

* List of generals of Manila

China

* List of generals of the People's Republic of China

India

* List of generals of Ranjit Singh

Europe France

* List of French generals of ...

*List of Ukrainians

This is a list of individuals who were born and lived in territories located in present-day Ukraine, including ethnic Ukrainians and those of other ethnicities.

Academics Mathematicians

* Selig Brodetsky (1888–1954), British mathematician, P ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Nikiforova, Maria Hryhorivna 1885 births 1919 deaths 20th-century executions by Russia 20th-century Ukrainian women politicians Anarchist partisans Anarcho-communists Anti-nationalism in Europe Executed anarchists Executed Ukrainian women Female revolutionaries French military personnel of World War I Intersex military personnel Intersex politicians Intersex women Makhnovshchina People convicted on terrorism charges People executed by Russia by firing squad Politicians from Zaporizhzhia People of the Russian Revolution People of the Russian Civil War Soviet people of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Ukrainian anarchists Ukrainian guerrillas Ukrainian rebels Ukrainian revolutionaries Ukrainian women in World War I Women in European warfare Women in war 1900–1945 Military personnel from Zaporizhzhia