Manchurian incident on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mukden Incident, or Manchurian Incident, known in Chinese as the 9.18 Incident (九・一八), was a

Japanese economic presence and political interest in Manchuria had been growing ever since the end of the

Japanese economic presence and political interest in Manchuria had been growing ever since the end of the

Believing that a conflict in Manchuria would be in the best interests of Japan, Kwantung Army Colonel

Believing that a conflict in Manchuria would be in the best interests of Japan, Kwantung Army Colonel

Colonel

Colonel  The plan was executed when 1st Lieutenant Suemori Komoto of the Independent Garrison Unit (獨立守備隊) of the 29th Infantry Regiment, which guarded the South Manchuria Railway, placed explosives near the tracks, but far enough away to do no real damage. At around 10:20 pm (22:20), September 18, the explosives were detonated. However, the explosion was minor and only a 1.5-meter section on one side of the rail was damaged. In fact, a train from Changchun passed by the site on this damaged track without difficulty and arrived in Shenyang at 10:30 pm (22:30).CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL EVENTS FROM 1931 THROUGH 1943, WITH OSTENSIBLE REASONS ADVANCED FOR THE OCCURRENCE THEREOF

The plan was executed when 1st Lieutenant Suemori Komoto of the Independent Garrison Unit (獨立守備隊) of the 29th Infantry Regiment, which guarded the South Manchuria Railway, placed explosives near the tracks, but far enough away to do no real damage. At around 10:20 pm (22:20), September 18, the explosives were detonated. However, the explosion was minor and only a 1.5-meter section on one side of the rail was damaged. In fact, a train from Changchun passed by the site on this damaged track without difficulty and arrived in Shenyang at 10:30 pm (22:30).CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL EVENTS FROM 1931 THROUGH 1943, WITH OSTENSIBLE REASONS ADVANCED FOR THE OCCURRENCE THEREOF

78th Congress, 2d Session. ''"An explosion undoubtedly occurred on or near the railroad between 10 and 10:30 p.m. on September 18th, but the damage, if any, to the railroad did not in fact prevent the punctual arrival of the south-bound train from Changchun, and was not in itself sufficient to justify military action. The military operations of the Japanese troops during this night, ... cannot be regarded as measures of legitimate self-defense..."'' pinion of Commission of Inquiry ibid., p. 71

Because of these circumstances, the central government turned to the international community for a peaceful resolution. The Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a strong protest to the Japanese government and called for the immediate stop to Japanese military operations in Manchuria, and appealed to the League of Nations, on September 19. On October 24, the League of Nations passed a resolution mandating the withdrawal of Japanese troops, to be completed by 16 November. However, Japan rejected the League of Nations resolution and insisted on direct negotiations with the Chinese government. Negotiations went on intermittently without much result.

On November 20, a conference in the Chinese government was convened, but the Guangzhou faction of the Kuomintang insisted that Chiang Kai-shek step down to take responsibility for the Manchurian debacle. On December 15, Chiang resigned as the Chairman of the Nationalist Government and was replaced as

Because of these circumstances, the central government turned to the international community for a peaceful resolution. The Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a strong protest to the Japanese government and called for the immediate stop to Japanese military operations in Manchuria, and appealed to the League of Nations, on September 19. On October 24, the League of Nations passed a resolution mandating the withdrawal of Japanese troops, to be completed by 16 November. However, Japan rejected the League of Nations resolution and insisted on direct negotiations with the Chinese government. Negotiations went on intermittently without much result.

On November 20, a conference in the Chinese government was convened, but the Guangzhou faction of the Kuomintang insisted that Chiang Kai-shek step down to take responsibility for the Manchurian debacle. On December 15, Chiang resigned as the Chairman of the Nationalist Government and was replaced as

online

* * Ogata, Sadako N. ''Defiance in Manchuria: the making of Japanese foreign policy, 1931-1932'' (U of California Press, 1964). * Yoshihashi, Takehiko. ''Conspiracy at Mukden: the rise of the Japanese military'' (Yale UP, 1963

online

* Wright, Quincy (1932-02). "The Manchurian Crisis". ''American Political Science Review''. 26 (1): 45–76.

World War II Database- Manchurian Incident

Article on Japanese military cliques and their involvement in The Mukden Incident from Japanese Press Translations 1945–46

{{Authority control Conflicts in 1931 Conflicts in 1932 Battles of the Second Sino-Japanese War Combat incidents False flag operations 1931 in China 1932 in China History of Manchuria 1931 in Japan 1932 in Japan League of Nations Acts of sabotage

false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext for the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

.

On September 18, 1931, Lieutenant Suemori Kawamoto of the Independent Garrison Unit of the 29th Japanese Infantry Regiment () detonated a small quantity of dynamite close to a railway line owned by Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

's South Manchuria Railway

The South Manchuria Railway ( ja, 南満州鉄道, translit=Minamimanshū Tetsudō; ), officially , Mantetsu ( ja, 満鉄, translit=Mantetsu) or Mantie () for short, was a large of the Empire of Japan whose primary function was the operatio ...

near Mukden (now Shenyang

Shenyang (, ; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly known as Fengtian () or by its Manchu name Mukden, is a major Chinese sub-provincial city and the provincial capital of Liaoning province. Located in central-north Liaoning, it is the provi ...

). The explosion was so weak that it failed to destroy the track, and a train passed over it minutes later. The Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emper ...

accused Chinese dissidents of the act and responded with a full invasion that led to the occupation of Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

, in which Japan established its puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

six months later. The deception was exposed by the Lytton Report

are the findings of the Lytton Commission, entrusted in 1931 by the League of Nations in an attempt to evaluate the Mukden Incident, which led to the Empire of Japan's Japanese invasion of Manchuria, seizure of Manchuria.

The five-member commiss ...

of 1932, leading Japan to diplomatic isolation and its March 1933 withdrawal from the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

.

The bombing act is known as the Liutiao Lake Incident (, Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

: , ''Ryūjōko-jiken''), and the entire episode of events is known in Japan as the Manchurian Incident (Kyūjitai

''Kyūjitai'' ( ja, 舊字體 / 旧字体, lit=old character forms) are the traditional forms of kanji, Chinese written characters used in Japanese. Their simplified counterparts are ''shinjitai'' ( ja, 新字体, lit=new character forms, la ...

: , Shinjitai

are the simplified forms of kanji used in Japan since the promulgation of the Tōyō Kanji List in 1946. Some of the new forms found in ''shinjitai'' are also found in Simplified Chinese characters, but ''shinjitai'' is generally not as extensi ...

: , ''Manshū-jihen'') and in China as the September 18 Incident ().

Background

Japanese economic presence and political interest in Manchuria had been growing ever since the end of the

Japanese economic presence and political interest in Manchuria had been growing ever since the end of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

(1904–1905). The Treaty of Portsmouth

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

that ended the war had granted Japan the lease of the South Manchuria Railway branch (from Changchun

Changchun (, ; ), also romanized as Ch'angch'un, is the capital and largest city of Jilin Province, People's Republic of China. Lying in the center of the Songliao Plain, Changchun is administered as a , comprising 7 districts, 1 county and 3 ...

to Lüshun) of the China Far East Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (al ...

. The Japanese government, however, claimed that this control included all the rights and privileges that China granted to Russia in the 1896 Li–Lobanov Treaty, as enlarged by the Kwantung Lease Agreement of 1898. This included absolute and exclusive administration within the South Manchuria Railway Zone

The South Manchuria Railway Zone ( ja, 南満州鉄道附属地, translit=Minami Manshū Tetsudō Fuzoku-chi; ) or SMR Zone, was the area of Japanese extraterritorial rights in northeast China, in connection with the operation of the South Man ...

. Japanese railway guards were stationed within the zone to provide security for the trains and tracks; however, these were regular Japanese soldiers, and they frequently carried out maneuvers outside the railway areas.

Meanwhile, the newly formed Chinese government was trying to reassert its authority over the country after over a decade of fragmented warlord dominance. They started to claim that treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

between China and Japan were invalid. China also announced new acts, so the Japanese people

The are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Japanese archipelago."人類学上は,旧石器時代あるいは縄文時代以来,現在の北海道〜沖縄諸島(南西諸島)に住んだ集団を祖先にもつ人々。" () Ja ...

(including Koreans

Koreans ( South Korean: , , North Korean: , ; see names of Korea) are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Korean Peninsula.

Koreans mainly live in the two Korean nation states: North Korea and South Korea (collectively and simply r ...

and Taiwanese

Taiwanese may refer to:

* Taiwanese language, another name for Taiwanese Hokkien

* Something from or related to Taiwan (Formosa)

* Taiwanese aborigines, the indigenous people of Taiwan

* Han Taiwanese, the Han people of Taiwan

* Taiwanese people, r ...

as both regions were under Japanese rule at this time) who had settled frontier lands, opened stores or built their own houses in China were expelled without any compensation. Manchurian warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

Chang Tso-lin tried to deprive Japanese concessions too, but he was assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

by the Japanese Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

. Chang Hsueh-liang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

, Chang Tso-lin's son and successor, joined the Nanjing Government led by Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

from anti-Japanese sentiment

Anti-Japanese sentiment (also called Japanophobia, Nipponophobia and anti-Japanism) involves the hatred or fear of anything which is Japanese, be it its culture or its people. Its opposite is Japanophilia.

Overview

Anti-Japanese sentim ...

. Official Japanese objections to the oppression against Japanese nationals within China were rejected by the Chinese authorities.

The 1929 Sino-Soviet conflict (July–November) over the Chinese Eastern Railroad

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

(CER) further increased the tensions in the Northeast that would lead to the Mukden Incident. The Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

victory over Chang Hsueh-liang's forces not only reasserted Soviet control over the CER in Manchuria but revealed Chinese military weaknesses that Japanese Kwantung Army officers were quick to note.

The Soviet Red Army performance also stunned Japanese officials. Manchuria was central to Japan's East Asia policy. Both the 1921 and 1927 Imperial Eastern Region Conferences reconfirmed Japan's commitment to be the dominant power in Manchuria. The 1929 Red Army victory shook that policy to the core and reopened the Manchurian problem. By 1930, the Kwantung Army realized they faced a Red Army that was only growing stronger. The time to act was drawing near and Japanese plans to conquer the Northeast were accelerated.

In April 1931, a national leadership conference of China was held between Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

and Chang Hsueh-liang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

in Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

. They agreed to put aside their differences and assert China's sovereignty in Manchuria strongly. On the other hand, some officers of the Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

began to plot to invade Manchuria secretly. There were other officers who wanted to support plotters in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

.

Events

Believing that a conflict in Manchuria would be in the best interests of Japan, Kwantung Army Colonel

Believing that a conflict in Manchuria would be in the best interests of Japan, Kwantung Army Colonel Seishirō Itagaki

was a Japanese military officer and politician who served as a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and War Minister from 1938 to 1939.

Itagaki was a main conspirator behind the Mukden Incident and held prestigious chief of ...

and Lieutenant Colonel Kanji Ishiwara independently devised a plan to prompt Japan to invade Manchuria by provoking an incident from Chinese forces stationed nearby. However, after the Japanese Minister of War Jirō Minami

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and Governor-General of Korea between 1936 and 1942. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Life and military career

Born to an ex-''samurai'' family in Hiji, Ōita Prefe ...

dispatched Major General Yoshitsugu Tatekawa

was a lieutenant-general in the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II. He played an important role in the Mukden Incident in 1931 and as Japanese ambassador to the Soviet Union he negotiated the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact in 1941.

Biograp ...

to Manchuria for the specific purpose of curbing the insubordination and militarist

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mil ...

behavior of the Kwantung Army, Itagaki and Ishiwara knew that they no longer had the luxury of waiting for the Chinese to respond to provocations, but had to stage their own.

Itagaki and Ishiwara chose to sabotage the rail section in an area near Liutiao Lake (; ''liǔtiáohú''). The area had no official name and was not militarily important, but it was only eight hundred meters away from the Chinese garrison of Beidaying (; ''běidàyíng''), where troops under the command of the "Young Marshal" Chang Hsueh-liang were stationed. The Japanese plan was to attract Chinese troops by an explosion and then blame them for having caused the disturbance in order to provide a pretext for a formal Japanese invasion. In addition, they intended to make the sabotage appear more convincing as a calculated Chinese attack on an essential target, thereby making the expected Japanese reaction appear as a legitimate measure to protect a vital railway of industrial and economic importance. The Japanese press labeled the site "Liǔtiáo Ditch" (; ''liǔtiáogōu'') or "Liǔtiáo Bridge" (; ''liǔtiáoqiáo''), when in reality, the site was a small railway section laid on an area of flat land. The choice to place the explosives at this site was to preclude the extensive rebuilding that would have been necessitated had the site actually been a railway bridge.

Incident

Colonel

Colonel Seishirō Itagaki

was a Japanese military officer and politician who served as a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and War Minister from 1938 to 1939.

Itagaki was a main conspirator behind the Mukden Incident and held prestigious chief of ...

, Lieutenant Colonel Kanji Ishiwara, Colonel Kenji Doihara

was a Japanese army officer. As a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, he was instrumental in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

As a leading intelligence officer, he played a key role to the Japanese machinations that ...

, and Major Takayoshi Tanaka had completed plans for the incident by May 31, 1931.

The plan was executed when 1st Lieutenant Suemori Komoto of the Independent Garrison Unit (獨立守備隊) of the 29th Infantry Regiment, which guarded the South Manchuria Railway, placed explosives near the tracks, but far enough away to do no real damage. At around 10:20 pm (22:20), September 18, the explosives were detonated. However, the explosion was minor and only a 1.5-meter section on one side of the rail was damaged. In fact, a train from Changchun passed by the site on this damaged track without difficulty and arrived in Shenyang at 10:30 pm (22:30).CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL EVENTS FROM 1931 THROUGH 1943, WITH OSTENSIBLE REASONS ADVANCED FOR THE OCCURRENCE THEREOF

The plan was executed when 1st Lieutenant Suemori Komoto of the Independent Garrison Unit (獨立守備隊) of the 29th Infantry Regiment, which guarded the South Manchuria Railway, placed explosives near the tracks, but far enough away to do no real damage. At around 10:20 pm (22:20), September 18, the explosives were detonated. However, the explosion was minor and only a 1.5-meter section on one side of the rail was damaged. In fact, a train from Changchun passed by the site on this damaged track without difficulty and arrived in Shenyang at 10:30 pm (22:30).CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR INTERNATIONAL EVENTS FROM 1931 THROUGH 1943, WITH OSTENSIBLE REASONS ADVANCED FOR THE OCCURRENCE THEREOF78th Congress, 2d Session. ''"An explosion undoubtedly occurred on or near the railroad between 10 and 10:30 p.m. on September 18th, but the damage, if any, to the railroad did not in fact prevent the punctual arrival of the south-bound train from Changchun, and was not in itself sufficient to justify military action. The military operations of the Japanese troops during this night, ... cannot be regarded as measures of legitimate self-defense..."'' pinion of Commission of Inquiry ibid., p. 71

Invasion of Manchuria

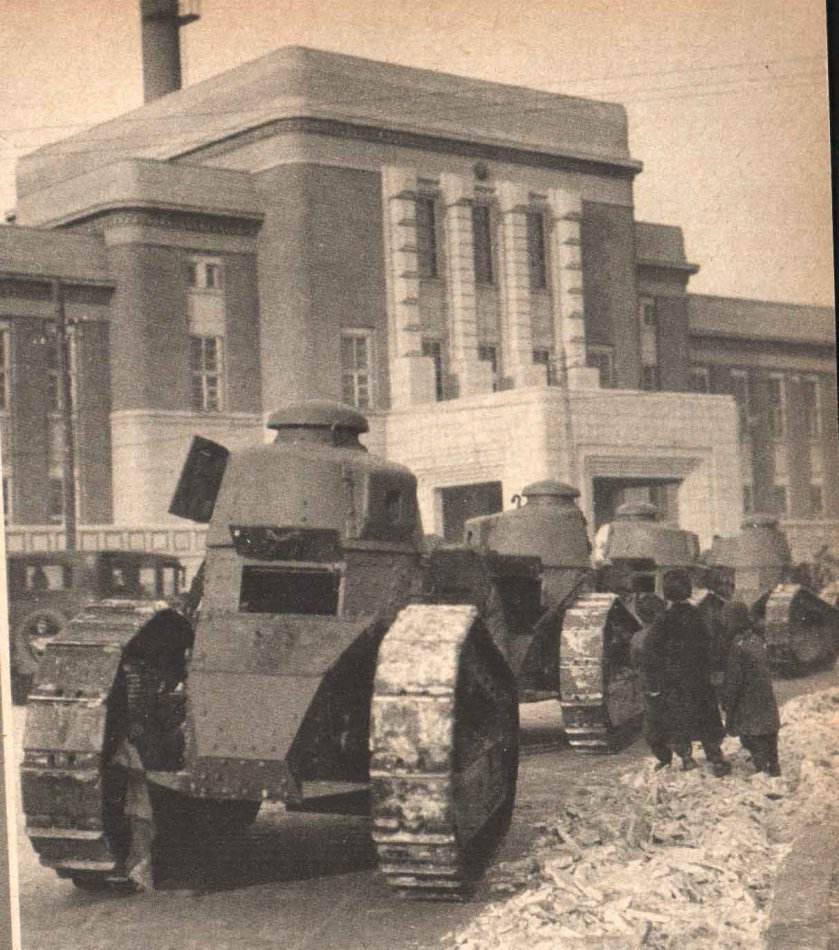

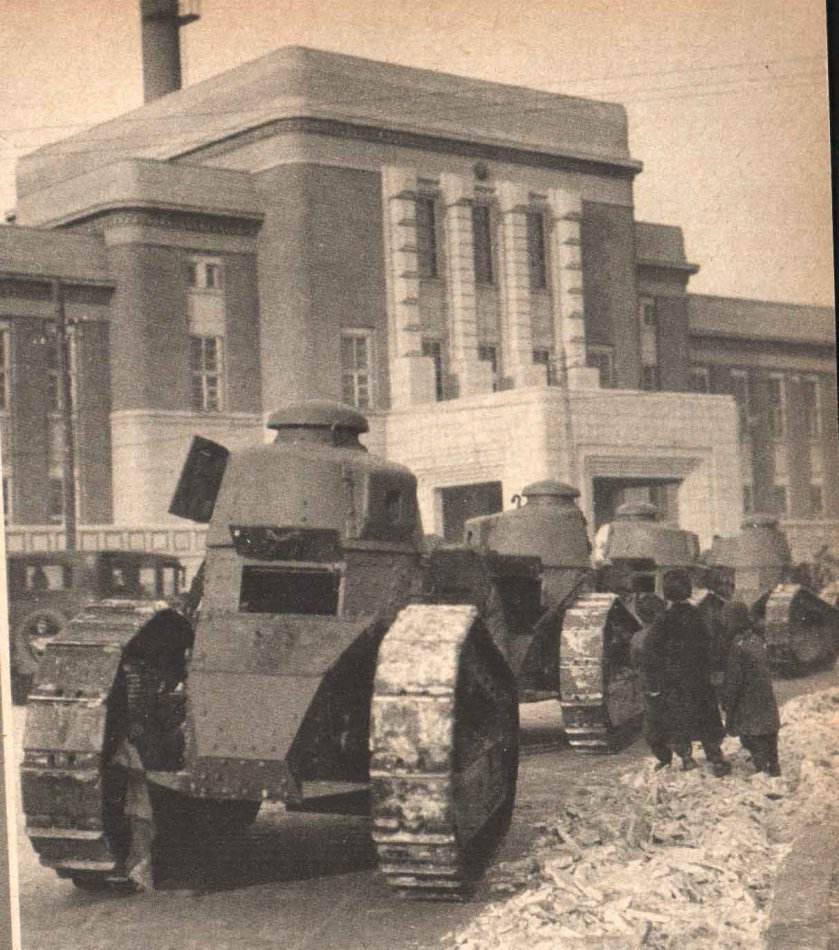

On the morning of September 19, two artillery pieces installed at theMukden

Shenyang (, ; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly known as Fengtian () or by its Manchu name Mukden, is a major Chinese sub-provincial city and the provincial capital of Liaoning province. Located in central-north Liaoning, it is the provinc ...

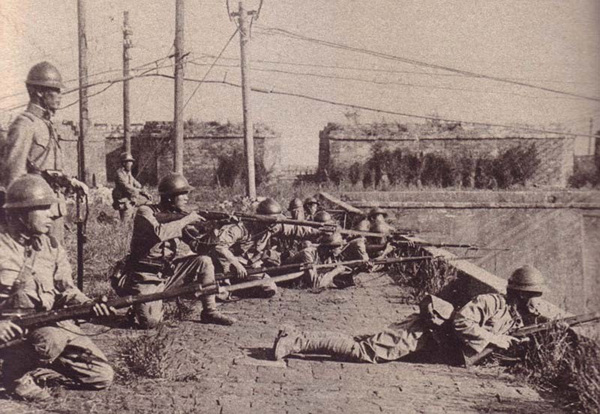

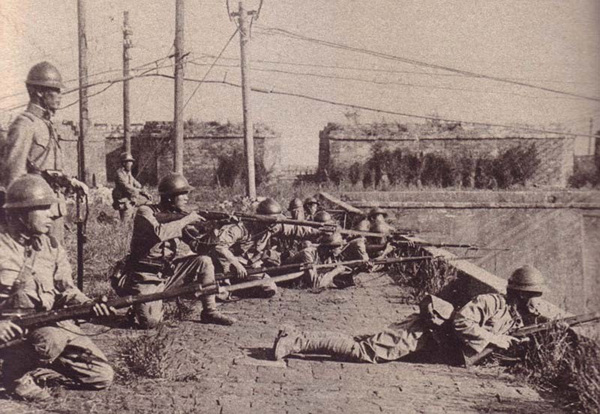

officers' club opened fire on the Chinese garrison nearby, in response to the alleged Chinese attack on the railway. Chang Hsueh-liang's small air force was destroyed, and his soldiers fled their destroyed Beidaying barracks, as five hundred Japanese troops attacked the Chinese garrison of around seven thousand. The Chinese troops were no match for the experienced Japanese troops. By the evening, the fighting was over, and the Japanese had occupied Mukden at the cost of five hundred Chinese lives and only two Japanese lives.

At Dalian

Dalian () is a major sub-provincial port city in Liaoning province, People's Republic of China, and is Liaoning's second largest city (after the provincial capital Shenyang) and the third-most populous city of Northeast China. Located on ...

in the Kwantung Leased Territory

The Kwantung Leased Territory ( ja, 關東州, ''Kantō-shū''; ) was a leased territory of the Empire of Japan in the Liaodong Peninsula from 1905 to 1945.

Japan first acquired Kwantung from the Qing Empire in perpetuity in 1895 in the Tr ...

, Commander-in-Chief of the Kwantung Army General Shigeru Honjō was at first appalled that the invasion plan was enacted without his permission, but he was eventually convinced by Ishiwara to give his approval after the act. Honjō moved the Kwantung Army headquarters to Mukden and ordered General Senjuro Hayashi of the Chosen Army of Japan

The was an army of the Imperial Japanese Army that formed a garrison force in Korea under Japanese rule. The Korean Army consisted of roughly 350,000 troops in 1914.

History

Japanese forces occupied large portions of the Empire of Korea du ...

in Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

to send in reinforcements. At 04:00 on 19 September, Mukden was declared secure.

Chang Hsueh-liang personally ordered his men not to put up a fight and to store away any weapons when the Japanese invaded. Therefore, the Japanese soldiers proceeded to occupy and garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mili ...

the major cities of Changchun and Antung

Andong / Antung ( Wade-Giles) (), or Liaodong () was a former province in Northeast China, located in what is now part of Liaoning and Jilin provinces. It was bordered on the southeast by the Yalu River, which separated it from Korea.

History

Th ...

and their surrounding areas with minimal difficulty. However, in November, General Ma Zhanshan, the acting governor of Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang () Postal romanization, formerly romanized as Heilungkiang, is a Provinces of China, province in northeast China. The standard one-character abbreviation for the province is (). It was formerly romanized as "Heilungkiang". It is th ...

, began resistance with his provincial army, followed in January by Generals Ting Chao

Ding Chao (; 1883–1950s) was a military general of the Republic of China, known for his defense of Harbin during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and 1932.

Biography

Ding Chao's forces commenced mobilization in November 1931 at the r ...

and Li Du

Li Du (; 1880–1956) was a leading general in the Jilin Self-Defence Army (JSDA). The JSDA was one of the Anti-Japanese volunteer armies led by general Ma Zhanshan which resisted the Empire of Japan's invasion of northeast China in 1932.

Follow ...

with their local Jilin

Jilin (; Postal romanization, alternately romanized as Kirin or Chilin) is one of the three Provinces of China, provinces of Northeast China. Its capital and largest city is Changchun. Jilin borders North Korea (Rasŏn, North Hamgyong, R ...

provincial forces. Despite this resistance, within five months of the Mukden Incident, the Imperial Japanese Army had overrun all major towns and cities in the provinces of Liaoning

Liaoning () is a coastal province in Northeast China that is the smallest, southernmost, and most populous province in the region. With its capital at Shenyang, it is located on the northern shore of the Yellow Sea, and is the northernmo ...

, Jilin

Jilin (; Postal romanization, alternately romanized as Kirin or Chilin) is one of the three Provinces of China, provinces of Northeast China. Its capital and largest city is Changchun. Jilin borders North Korea (Rasŏn, North Hamgyong, R ...

, and Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang () Postal romanization, formerly romanized as Heilungkiang, is a Provinces of China, province in northeast China. The standard one-character abbreviation for the province is (). It was formerly romanized as "Heilungkiang". It is th ...

.

Aftermath

Chinese public opinion strongly criticized Chang Hsueh-liang for his non-resistance to the Japanese invasion. While the Japanese presented a real threat, the Kuomintang directed most of their efforts towards eradication of the communist party. Many charged that Chang'sNortheastern Army

The Northeastern Army (), was the Chinese army of the Fengtien clique until the unification of China in 1928. From 1931 to 1933 it faced the Japanese forces in northeast China, Jehol and Hebei, in the early years of the Second Sino-Japanese Wa ...

of nearly a quarter million could have withstood the Kwantung Army of only 11,000 men. In addition, his arsenal in Manchuria was considered the most modern in China, and his troops had possession of tanks, around 60 combat aircraft, 4000 machine guns, and four artillery battalions.

Chang Hsueh-liang's seemingly superior force was undermined by several factors. The first was that the Kwantung Army had a strong reserve force that could be transported by railway from Korea, which was a Japanese colony, directly adjacent to Manchuria. Secondly, more than half of Chang's troops were stationed south of the Great Wall

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand Li (unit), ''li'' wall") is a series of fortifications that were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against Eurasian noma ...

in Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and ...

Province, while the troops north of the wall were scattered throughout Manchuria. Therefore, deploying Chang's troops north of the Great Wall meant that they lacked the concentration needed to fight the Japanese effectively. Most of Chang's troops were under-trained, poorly led, poorly fed, and had poor morale and questionable loyalty compared to their Japanese counterparts. Japanese secret agents had permeated Chang's command because of his and his father Chang Tso-lin's past reliance on Japanese military advisers. The Japanese knew the Northeastern Army very well and were able to conduct operations with ease.

The Chinese government was preoccupied with numerous internal problems, including the issue of the newly independent Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, sou ...

government of Hu Hanmin

Hu Hanmin (; born in Panyu, Guangdong, Qing dynasty, China, 9 December 1879 – Kwangtung, Republic of China, 12 May 1936) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was one of the early conservative right factional leaders in the Kuomintang ...

, Communist Party of China

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

insurrections, and terrible flooding of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

that created tens of thousands of refugees. Moreover, Chang himself was not in Manchuria at the time, but was in a hospital in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

to raise money for the flood victims. However, in the Chinese newspapers, Chang was ridiculed as "General Nonresistance" ().

Because of these circumstances, the central government turned to the international community for a peaceful resolution. The Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a strong protest to the Japanese government and called for the immediate stop to Japanese military operations in Manchuria, and appealed to the League of Nations, on September 19. On October 24, the League of Nations passed a resolution mandating the withdrawal of Japanese troops, to be completed by 16 November. However, Japan rejected the League of Nations resolution and insisted on direct negotiations with the Chinese government. Negotiations went on intermittently without much result.

On November 20, a conference in the Chinese government was convened, but the Guangzhou faction of the Kuomintang insisted that Chiang Kai-shek step down to take responsibility for the Manchurian debacle. On December 15, Chiang resigned as the Chairman of the Nationalist Government and was replaced as

Because of these circumstances, the central government turned to the international community for a peaceful resolution. The Chinese Foreign Ministry issued a strong protest to the Japanese government and called for the immediate stop to Japanese military operations in Manchuria, and appealed to the League of Nations, on September 19. On October 24, the League of Nations passed a resolution mandating the withdrawal of Japanese troops, to be completed by 16 November. However, Japan rejected the League of Nations resolution and insisted on direct negotiations with the Chinese government. Negotiations went on intermittently without much result.

On November 20, a conference in the Chinese government was convened, but the Guangzhou faction of the Kuomintang insisted that Chiang Kai-shek step down to take responsibility for the Manchurian debacle. On December 15, Chiang resigned as the Chairman of the Nationalist Government and was replaced as Premier of the Republic of China

The Premier of the Republic of China, officially the President of the Executive Yuan ( Chinese: 行政院院長), is the head of the government of the Republic of China of Taiwan and leader of the Executive Yuan. The premier is nominally the ...

(head of the Executive Yuan

The Executive Yuan () is the executive branch of the government of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Its leader is the Premier, who is appointed by the President of the Republic of China, and requires confirmation by the Legislative Yuan.

...

) by Sun Fo

Sun Fo or Sun Ke (; 21 October 1891 – 13 September 1973), courtesy name Zhesheng (), was a high-ranking official in the government of the Republic of China. He was the son of Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China, and his fir ...

, son of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

. Jinzhou

Jinzhou (, ), formerly Chinchow, is a coastal prefecture-level city in central-west Liaoning province, China. It is a geographically strategic city located in the Liaoxi Corridor, which connects most of the land transports between North Chin ...

, another city in Liaoning, was lost to the Japanese in early January 1932. As a result, Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

replaced Sun Fo as the Premier.

On January 7, 1932, United States Secretary of State Henry Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and D ...

issued his Stimson Doctrine

The Stimson Doctrine is the policy of nonrecognition of states created as a result of a war of aggression. The policy was implemented by the United States government, enunciated in a note of January 7, 1932, to the Empire of Japan and the Repub ...

, that the United States would not recognize any government that was established as the result of Japanese actions in Manchuria. On January 14, a League of Nations commission, headed by Victor Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton

Victor Alexander George Robert Bulwer-Lytton, 2nd Earl of Lytton, (9 August 1876 – 25 October 1947), styled Viscount Knebworth from 1880 to 1891, was a British politician and colonial administrator. He served as Governor of Bengal between 192 ...

, disembarked at Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

to examine the situation. In March, the puppet state of Manchukuo

Manchukuo, officially the State of Manchuria prior to 1934 and the Empire of (Great) Manchuria after 1934, was a puppet state of the Empire of Japan in Manchuria from 1932 until 1945. It was founded as a republic in 1932 after the Japanese ...

was established, with the former emperor of China, Puyi

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

, installed as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

.Nish, ''Japan's Struggle with Internationalism: Japan, China, and the League of Nations, 1931–3'' (1993).

On October 2, the Lytton Report

are the findings of the Lytton Commission, entrusted in 1931 by the League of Nations in an attempt to evaluate the Mukden Incident, which led to the Empire of Japan's Japanese invasion of Manchuria, seizure of Manchuria.

The five-member commiss ...

was published and rejected the Japanese claim that the Manchurian invasion and occupation was an act of self-defense, although it did not assert that the Japanese had perpetrated the initial bombing of the railroad. The report ascertained that Manchukuo was the product of Japanese military aggression in China, while recognizing that Japan had legitimate concerns in Manchuria because of its economic ties there. The League of Nations refused to acknowledge Manchukuo as an independent nation. Japan resigned from the League of Nations in March 1933.

Colonel Kenji Doihara used the Mukden Incident to continue his campaign of disinformation. Since the Chinese troops at Mukden had put up such poor resistance, he told Manchukuo Emperor Puyi that this was proof that the Chinese remained loyal to him. Japanese intelligence used the incident to continue the campaign to discredit the murdered Chang Tso-lin and his son Chang Hsueh-liang for "misgovernment" of Manchuria. In fact, drug trafficking and corruption had largely been suppressed under Chang Tso-lin.

Controversy

Different opinions still exist as to who caused the explosion on the Japanese railroad at Mukden. Strong evidence points to young officers of the Japanese Kwantung Army having conspired to cause the blast, with or without direct orders fromTokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

. Post-war investigations confirmed that the original bomb planted by the Japanese failed to explode, and a replacement had to be planted. The resulting explosion enabled the Japanese Kwantung Army to accomplish their goal of triggering a conflict with Chinese troops stationed in Manchuria and the subsequent establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo.

The 9.18 Incident Exhibition Museum (九・一八歷史博物館) at Shenyang, opened by the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

on September 18, 1991, takes the position that the explosives were planted by Japan. The Yūshūkan

The ("Place to commune with a noble soul") is a Japanese military and war museum located within Yasukuni Shrine in Chiyoda, Tokyo. As a museum maintained by the shrine, which is dedicated to the souls of soldiers who died fighting on behalf of th ...

museum, located within Yasukuni Shrine

is a Shinto shrine located in Chiyoda, Tokyo. It was founded by Emperor Meiji in June 1869 and commemorates those who died in service of Japan, from the Boshin War of 1868–1869, to the two Sino-Japanese Wars, 1894–1895 and 1937–1945 resp ...

in Tokyo, also places the blame on members of the Kwantung Army.

David Bergamini

David Howland Bergamini (11 October 1928 – 3 September 1983, in Tokyo) was an American author who wrote books on 20th-century history and popular science, notably mathematics.

Bergamini was interned as an Allied civilian in a Japanese concentr ...

's book ''Japan's Imperial Conspiracy'' (1971) has a detailed chronology of events in both Manchuria and Tokyo surrounding the Mukden Incident. Bergamini concludes that the greatest deception was that the Mukden Incident and Japanese invasion were planned by junior or hot-headed officers, without formal approval by the Japanese government. However, historian James Weland has concluded that senior commanders had tacitly allowed field operatives to proceed on their own initiative, then endorsed the result after a positive outcome was assured.

In August 2006, the ''Yomiuri Shimbun

The (lit. ''Reading-selling Newspaper'' or ''Selling by Reading Newspaper'') is a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka, and other major Japanese cities. It is one of the five major newspapers in Japan; the other four are ...

'', Japan's top-selling newspaper, published the results of a year-long research project into the general question of who was responsible for the " Shōwa war". With respect to the Manchurian Incident, the newspaper blamed ambitious Japanese militarists, as well as politicians who were impotent to rein them in or prevent their insubordination.

Debate has also focused on how the incident was handled by the League of Nations and the subsequent Lytton Report. A. J. P. Taylor wrote that "In the face of its first serious challenge", the League buckled and capitulated. The Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

(1921) guaranteed a certain degree of Japanese hegemony in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

. Any intervention on the part of America would be a breach of the already mentioned agreement. Furthermore, Britain was in crisis, having been recently forced off the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from th ...

. Although a power in East Asia at the time, Britain was incapable of decisive action. The only response from these powers was "moral condemnation".

Remembrance

Each year at 10:00 am on 18 September, air-raid sirens sound for several minutes in numerous major cities across China. Provinces include Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Hainan, and others.In popular culture

* The Mukden Incident is depicted in ''The Adventures of Tintin

''The Adventures of Tintin'' (french: Les Aventures de Tintin ) is a series of 24 bande dessinée#Formats, ''bande dessinée'' albums created by Belgians, Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, who wrote under the pen name Hergé. The series was one ...

'' comic ''The Blue Lotus

''The Blue Lotus'' (french: link=no, Le Lotus bleu) is the fifth volume of ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Commissioned by the conservative Belgian newspaper for its children's supplement , it wa ...

'', although the book places the bombing near Shanghai. Here it is performed by Japanese agents and the Japanese exaggerate the incident.

* The Chinese patriotic song ''Along the Songhua River

"Along the Songhua River" () is a patriotic song from the War of Resistance in both the Republic of China (now in Taiwan) and the People's Republic of China.

History

The song describes the lives of the people who had lost their homeland along th ...

'' describes the lives of the people who had lost their homeland in Northeast China after the Mukden Incident.

* In Akira Kurosawa's 1946 film ''No Regrets for Our Youth

is a 1946 Japanese film written and directed by Akira Kurosawa. It is based on the 1933 Takigawa incident.

The film stars Setsuko Hara, Susumu Fujita, Takashi Shimura and Denjirō Ōkōchi. Fujita's character was inspired by the real-life Hotsumi ...

'', the subject of the Mukden Incident is debated.

* See also Junji Kinoshita

was the foremost playwright of modern drama in postwar Japan. He was also a translator and scholar of Shakespeare's plays. Kinoshita’s achievements were not limited to Japan.Kinoshita, Junji. Between God and Man: A Judgment on War Crimes: a Play ...

's play ''A Japanese Called Otto'',''Patriots and Traitors: Sorge and Ozaki: A Japanese Cultural Casebook'', MerwinAsia: 2009, pp. 101–197 which opens with the characters discussing the Mukden Incident.

* The 2010 Japanese anime

is Traditional animation, hand-drawn and computer animation, computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside of Japan and in English, ''anime'' refers specifically to animation produced in Japan. However, in Japan and in Japane ...

''Night Raid 1931

, is a Japanese anime television series produced by A-1 Pictures and Aniplex and directed by Atsushi Matsumoto. The 13-episode anime aired in Japan on the TV Tokyo television network starting April 5, 2010. ''Senkō no Night Raid'' is the secon ...

'' is a 13-episode spy/pulp series set in 1931 Shanghai and Manchuria. Episode 7, "Incident", specifically covers the Mukden Incident.

* The violent manga

Manga ( Japanese: 漫画 ) are comics or graphic novels originating from Japan. Most manga conform to a style developed in Japan in the late 19th century, and the form has a long prehistory in earlier Japanese art. The term ''manga'' is ...

''Gantz

''Gantz'' (stylized as ''GANTZ'') is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Hiroya Oku. It was serialized in Shueisha's ''seinen'' manga magazine ''Weekly Young Jump'' from June 2000 to June 2013, with its chapters collected i ...

'' has a reference when an elder says that an occurrence reminds him of the "Manchurian Incident".

* Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

death metal

Death metal is an extreme subgenre of heavy metal music. It typically employs heavily distorted and low-tuned guitars, played with techniques such as palm muting and tremolo picking; deep growling vocals; aggressive, powerful drumming, fe ...

band Hail of Bullets

Hail of Bullets was a Dutch old school death metal supergroup from Rotterdam. The band's lyrical content deals with the Second World War, and is based upon the research of vocalist Martin van Drunen, who has been described as the band's "resident ...

covers the event in the song "The Mukden Incident" on their 2010 album ''On Divine Winds

''On Divine Winds'' is the second album from Hail of Bullets, an old school death metal band formed by current and former members of Asphyx and Gorefest. ''On Divine Winds'' continued the band's focus upon the Second World War, this time focusi ...

'', a concept album

A concept album is an album whose tracks hold a larger purpose or meaning collectively than they do individually. This is typically achieved through a single central narrative or theme, which can be instrumental, compositional, or lyrical. Some ...

about the Pacific Ocean theatre of World War II

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.

* The television drama ''Kazoku Game'' () deals with the history textbook controversy in episode 4, mentioning the Mukden Incident.

* The 1969 novel black rain by Masuji Ibuse mentions the incident on numerous occasions.

See also

* Events preceding World War II in Asia ** Jinan incident (May 1928) **Huanggutun incident

The Huanggutun incident (), also known as the , was the assassination of the Fengtian warlord and Generalissimo of the Military Government of China Zhang Zuolin near Shenyang on 4 June 1928.

Zhang was killed when his personal train was destroy ...

(Japanese assassination of the Chinese head of state Generalissimo Zhang Zuolin

Zhang Zuolin (; March 19, 1875 June 4, 1928), courtesy name Yuting (雨亭), nicknamed Zhang Laogang (張老疙瘩), was an influential Chinese bandit, soldier, and warlord during the Warlord Era in China. The warlord of Manchuria from 1916 to ...

on 4 June 1928)

** Northeast Flag Replacement (by Zhang Xueliang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

on 29 December 1928)

* Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

** Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

(1931)

** January 28 Incident (Shanghai, 1932)

** Defense of the Great Wall

The defense of the Great Wall () (January 1 – May 31, 1933) was a campaign between the armies of Republic of China and Empire of Japan, which took place before the Second Sino-Japanese War officially commenced in 1937 and after the Japanese in ...

(1933)

** Marco Polo Bridge Incident

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident, also known as the Lugou Bridge Incident () or the July 7 Incident (), was a July 1937 battle between China's National Revolutionary Army and the Imperial Japanese Army.

Since the Japanese invasion of Manchuri ...

(7 July 1937)

* History of Sino-Japanese relations#Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II

* History of the Republic of China

The history of the Republic of China begins after the Qing dynasty in 1912, when the Xinhai Revolution and the formation of the Republic of China put an end to 2,000 years of imperial rule. The Republic experienced many trials and tribulations a ...

* Military of the Republic of China

The Republic of China Armed Forces (ROC Armed Forces) are the armed forces of the Taiwan, Republic of China (ROC), Republic of China (1912–1949), once based in mainland China and currently in its Free area of the Republic of China, remainin ...

* National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * * Lucas, David G. ''Strategic Disharmony: Japan, Manchuria, and Foreign Policy'' (Air War College, 1995online

* * Ogata, Sadako N. ''Defiance in Manchuria: the making of Japanese foreign policy, 1931-1932'' (U of California Press, 1964). * Yoshihashi, Takehiko. ''Conspiracy at Mukden: the rise of the Japanese military'' (Yale UP, 1963

online

* Wright, Quincy (1932-02). "The Manchurian Crisis". ''American Political Science Review''. 26 (1): 45–76.

External links

World War II Database- Manchurian Incident

Article on Japanese military cliques and their involvement in The Mukden Incident from Japanese Press Translations 1945–46

{{Authority control Conflicts in 1931 Conflicts in 1932 Battles of the Second Sino-Japanese War Combat incidents False flag operations 1931 in China 1932 in China History of Manchuria 1931 in Japan 1932 in Japan League of Nations Acts of sabotage