Mammoth Cave on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mammoth Cave National Park is an American

As stated in the foundation document:

As stated in the foundation document:

The limestone layers of the

The limestone layers of the

The

The

The story of human beings in relation to Mammoth Cave spans five thousand years. Several sets of Native American remains have been recovered from Mammoth Cave, or other nearby caves in the region, in both the 19th and 20th centuries. Most

The story of human beings in relation to Mammoth Cave spans five thousand years. Several sets of Native American remains have been recovered from Mammoth Cave, or other nearby caves in the region, in both the 19th and 20th centuries. Most

Legend has it that the first European to visit Mammoth Cave was either John Houchin or his brother Francis Houchin, in 1797. While hunting, Houchin pursued a wounded bear to the cave's large entrance opening near the Green River. Some Houchin Family tales have John Decatur "Johnny Dick" Houchin as the discoverer of the cave, but this is highly unlikely because Johnny Dick was only 10 years old in 1797 and was unlikely to be out hunting bears at such an age. His father John is the more likely candidate from that branch of the family tree, but the most probable candidate for discoverer of Mammoth Cave is Francis "Frank" Houchin, whose land was much closer to the cave entrance than his brother John's. There is also the argument that their brother Charles Houchin, who was known as a great hunter and trapper, was the man who shot that bear and chased it into the cave. The shadow over Charles's claim is the fact that he was residing in Illinois until 1801. Contrary to this story is Brucker and Watson's ''The Longest Cave'', which asserts that the cave was "certainly known before that time." Caves in the area were known before the discovery of the entrance to Mammoth Cave. Even Francis Houchin had a cave entrance on his land very near the bend in the Green River known as the Turnhole, which is less than a mile from the main entrance of Mammoth Cave.

The land containing this historic entrance was first surveyed and registered in 1798 under the name of Valentine Simons. Simons began exploiting Mammoth Cave for its

Legend has it that the first European to visit Mammoth Cave was either John Houchin or his brother Francis Houchin, in 1797. While hunting, Houchin pursued a wounded bear to the cave's large entrance opening near the Green River. Some Houchin Family tales have John Decatur "Johnny Dick" Houchin as the discoverer of the cave, but this is highly unlikely because Johnny Dick was only 10 years old in 1797 and was unlikely to be out hunting bears at such an age. His father John is the more likely candidate from that branch of the family tree, but the most probable candidate for discoverer of Mammoth Cave is Francis "Frank" Houchin, whose land was much closer to the cave entrance than his brother John's. There is also the argument that their brother Charles Houchin, who was known as a great hunter and trapper, was the man who shot that bear and chased it into the cave. The shadow over Charles's claim is the fact that he was residing in Illinois until 1801. Contrary to this story is Brucker and Watson's ''The Longest Cave'', which asserts that the cave was "certainly known before that time." Caves in the area were known before the discovery of the entrance to Mammoth Cave. Even Francis Houchin had a cave entrance on his land very near the bend in the Green River known as the Turnhole, which is less than a mile from the main entrance of Mammoth Cave.

The land containing this historic entrance was first surveyed and registered in 1798 under the name of Valentine Simons. Simons began exploiting Mammoth Cave for its

In partnership with Valentine Simon, various other individuals would own the land through the

In partnership with Valentine Simon, various other individuals would own the land through the  In 1839,

In 1839,

The difficulties of farming life in the hardscrabble, poor soil of the cave-country influenced local owners of smaller nearby caves to see opportunities for commercial exploitation, particularly given the success of Mammoth Cave as a tourist attraction. The "Kentucky Cave Wars" was a period of bitter competition between local cave owners for tourist money. Broad tactics of deception were used to lure visitors away from their intended destination to other private show caves. Misleading signs were placed along the roads leading to the Mammoth Cave. A typical strategy during the early days of automobile travel involved representatives (known as "cappers") of other private show caves hopping aboard a tourist's car's running board, and leading the passengers to believe that Mammoth Cave was closed, quarantined, caved in or otherwise inaccessible.

In 1906, Mammoth Cave became accessible by

The difficulties of farming life in the hardscrabble, poor soil of the cave-country influenced local owners of smaller nearby caves to see opportunities for commercial exploitation, particularly given the success of Mammoth Cave as a tourist attraction. The "Kentucky Cave Wars" was a period of bitter competition between local cave owners for tourist money. Broad tactics of deception were used to lure visitors away from their intended destination to other private show caves. Misleading signs were placed along the roads leading to the Mammoth Cave. A typical strategy during the early days of automobile travel involved representatives (known as "cappers") of other private show caves hopping aboard a tourist's car's running board, and leading the passengers to believe that Mammoth Cave was closed, quarantined, caved in or otherwise inaccessible.

In 1906, Mammoth Cave became accessible by  Famed French cave explorer

Famed French cave explorer

As the last of the Croghan heirs died, advocacy momentum grew among wealthy citizens of Kentucky for the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. Private citizens formed the Mammoth Cave National Park Association in 1924. The park was authorized May 25, 1926.

Donated funds were used to purchase some farmsteads in the region, while other tracts within the proposed national park boundary were acquired by right of

As the last of the Croghan heirs died, advocacy momentum grew among wealthy citizens of Kentucky for the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. Private citizens formed the Mammoth Cave National Park Association in 1924. The park was authorized May 25, 1926.

Donated funds were used to purchase some farmsteads in the region, while other tracts within the proposed national park boundary were acquired by right of

Mammoth Cave National Park was officially dedicated on July 1, 1941. By coincidence, the same year saw the incorporation of the

Mammoth Cave National Park was officially dedicated on July 1, 1941. By coincidence, the same year saw the incorporation of the

By 1954, Mammoth Cave National Park's land holdings encompassed all lands within its outer boundary with the exception of two privately held tracts. One of these, the old Lee Collins farm, had been sold to Harry Thomas of Horse Cave, Kentucky, whose grandson, William "Bill" Austin, operated Collins Crystal Cave as a show cave in direct competition with the national park, which was forced to maintain roads leading to the property.

In February 1954, a two-week expedition under the auspices of the

By 1954, Mammoth Cave National Park's land holdings encompassed all lands within its outer boundary with the exception of two privately held tracts. One of these, the old Lee Collins farm, had been sold to Harry Thomas of Horse Cave, Kentucky, whose grandson, William "Bill" Austin, operated Collins Crystal Cave as a show cave in direct competition with the national park, which was forced to maintain roads leading to the property.

In February 1954, a two-week expedition under the auspices of the

During the 1960s, Cave Research Foundation (CRF) exploration and mapping teams had found passageways in the Flint Ridge Cave System that penetrated under Houchins Valley and came within of known passages in Mammoth Cave. In 1972, CRF Chief Cartographer John Wilcox pursued an aggressive program to finally connect the caves, fielding several expeditions from the Flint Ridge side as well as exploring leads in Mammoth Cave.

On a July 1972 trip, deep in the Flint Ridge Cave System, Patricia Crowther—with her slight frame of —crawled through a narrow canyon later dubbed the "Tight Spot", which acted as a filter for larger cavers. A subsequent trip past the Tight Spot on August 30, 1972, by Wilcox, Crowther, Richard Zopf, and Tom Brucker discovered the name "Pete H" inscribed on the wall of a river passage with an arrow pointing in the direction of Mammoth Cave. The name is believed to have been carved by Warner P. "Pete" Hanson, who was active in exploring the cave in the 1930s. Hanson had been killed in

During the 1960s, Cave Research Foundation (CRF) exploration and mapping teams had found passageways in the Flint Ridge Cave System that penetrated under Houchins Valley and came within of known passages in Mammoth Cave. In 1972, CRF Chief Cartographer John Wilcox pursued an aggressive program to finally connect the caves, fielding several expeditions from the Flint Ridge side as well as exploring leads in Mammoth Cave.

On a July 1972 trip, deep in the Flint Ridge Cave System, Patricia Crowther—with her slight frame of —crawled through a narrow canyon later dubbed the "Tight Spot", which acted as a filter for larger cavers. A subsequent trip past the Tight Spot on August 30, 1972, by Wilcox, Crowther, Richard Zopf, and Tom Brucker discovered the name "Pete H" inscribed on the wall of a river passage with an arrow pointing in the direction of Mammoth Cave. The name is believed to have been carved by Warner P. "Pete" Hanson, who was active in exploring the cave in the 1930s. Hanson had been killed in

Further connections between Mammoth Cave and smaller caves or cave systems have followed, notably to Proctor/Morrison Cave beneath nearby Joppa Ridge in 1979. Proctor Cave was discovered by Jonathan Doyle, a Union Army deserter during the Civil War, and was later owned by the Mammoth Cave Railroad, before being explored by the CRF. Morrison cave was discovered by George Morrison in the 1920s. This connection pushed the frontier of Mammoth exploration southeastward.

At the same time, discoveries made outside the park by an independent group called the Central Kentucky Karst Coalition or CKKC resulted in the survey of tens of miles in Roppel Cave east of the park. Discovered in 1976, Roppel Cave was briefly on the list of the nation's longest caves before it was connected to the Proctor/Morrison's section of the Mammoth Cave System on September 10, 1983. The connection was made by two mixed parties of CRF and CKKC explorers. Each party entered through a separate entrance and met in the middle before continuing in the same direction to exit at the opposite entrance. The resulting total surveyed length was near .

On March 19, 2005, a connection into the Roppel Cave portion of the system was surveyed from a small cave under Eudora Ridge, adding approximately three miles to the known length of the Mammoth Cave System. The newly found entrance to the cave, now termed the "Hoover Entrance", had been discovered in September 2003, by Alan Canon and James Wells. Incremental discoveries since then have pushed the total to more than .

It is certain that many more miles of cave passages await discovery in the region. Discovery of new natural entrances is a rare event: the primary mode of discovery involves the pursuit of side passages identified during routine systematic exploration of cave passages entered from known entrances.

Further connections between Mammoth Cave and smaller caves or cave systems have followed, notably to Proctor/Morrison Cave beneath nearby Joppa Ridge in 1979. Proctor Cave was discovered by Jonathan Doyle, a Union Army deserter during the Civil War, and was later owned by the Mammoth Cave Railroad, before being explored by the CRF. Morrison cave was discovered by George Morrison in the 1920s. This connection pushed the frontier of Mammoth exploration southeastward.

At the same time, discoveries made outside the park by an independent group called the Central Kentucky Karst Coalition or CKKC resulted in the survey of tens of miles in Roppel Cave east of the park. Discovered in 1976, Roppel Cave was briefly on the list of the nation's longest caves before it was connected to the Proctor/Morrison's section of the Mammoth Cave System on September 10, 1983. The connection was made by two mixed parties of CRF and CKKC explorers. Each party entered through a separate entrance and met in the middle before continuing in the same direction to exit at the opposite entrance. The resulting total surveyed length was near .

On March 19, 2005, a connection into the Roppel Cave portion of the system was surveyed from a small cave under Eudora Ridge, adding approximately three miles to the known length of the Mammoth Cave System. The newly found entrance to the cave, now termed the "Hoover Entrance", had been discovered in September 2003, by Alan Canon and James Wells. Incremental discoveries since then have pushed the total to more than .

It is certain that many more miles of cave passages await discovery in the region. Discovery of new natural entrances is a rare event: the primary mode of discovery involves the pursuit of side passages identified during routine systematic exploration of cave passages entered from known entrances.

Bridwell 1952 (inside back cover)

Faithful Visitor

First Park Superintendent R. Taylor Hoskins describes the yearly visits of "Pete" a tame summer tanager (''Piranga rubra''). In ''The Regional Review'', Vol VII, 1 and 2 (July–August 1941) * Hovey, Horace Carter (Hovey 1880) ''One Hundred Miles in Mammoth Cave in 1880: an early exploration of America's most famous cavern''. with introductory note by William R. Jones. Golden, Colorado: Outbooks. (Copyright 1982) * Hovey, Horace Carter ''Hovey's Handbook of The Mammoth Cave of Kentucky: A Practical Guide to the Regulation Routes''. (John P. Morton & Company, Louisville, Kentucky, 1909)

Full text transcription

* * Watson, Richard A., ed. (Watson 1981) ''The Cave Research Foundation: Origins and the First Twelve Years 1957–1968'' Mammoth Cave, Kentucky: Cave Research Foundation.

Mammoth Cave National Park website

Mammoth Cave National Park Association website

*

* {{Authority control Caves of Kentucky Historic American Engineering Record in Kentucky Limestone caves National parks in Kentucky Archaeological sites in Kentucky Show caves in the United States Civilian Conservation Corps in Kentucky Protected areas of Edmonson County, Kentucky Protected areas of Hart County, Kentucky Protected areas of Barren County, Kentucky Protected areas established in 1941 1941 establishments in Kentucky Biosphere reserves of the United States World Heritage Sites in the United States Landforms of Edmonson County, Kentucky Landforms of Hart County, Kentucky Landforms of Barren County, Kentucky

national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

in west-central Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, encompassing portions of Mammoth Cave, the longest cave system known in the world.

Since the 1972 unification of Mammoth Cave with the even-longer system under Flint Ridge to the north, the official name of the system has been the Mammoth–Flint Ridge Cave System. The park was established as a national park on July 1, 1941, a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

on October 27, 1981, an international Biosphere Reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

on September 26, 1990 and an International Dark Sky Park on October 28, 2021.

The park's are located primarily in Edmonson County

Edmonson County is a county located in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,126. Its county seat is Brownsville. The county was formed in 1825 and named for Captain John "Jack ...

, with small areas extending eastward into Hart and Barren

Barren primarily refers to a state of barrenness (infertility

Infertility is the inability of a person, animal or plant to reproduce by natural means. It is usually not the natural state of a healthy adult, except notably among certain eusoc ...

counties. The Green River runs through the park, with a tributary

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drai ...

called the Nolin River feeding into the Green just inside the park. Mammoth Cave is the world's longest known cave system with more than of surveyed passageways, which is nearly twice as long as the second-longest cave system, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

's Sac Actun underwater cave.

Park purpose

As stated in the foundation document:

As stated in the foundation document:

Geology

Mammoth Cave developed in thick Mississippian-agedlimestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

capped by a layer of sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

, which has made the system remarkably stable. It is known to include more than of passageway. New discoveries and connections add several miles to this figure each year. Mammoth Cave National Park was established to preserve the cave system.

The upper sandstone member is known as the Big Clifty Sandstone. Thin, sparse layers of limestone interspersed within the sandstone give rise to an epikarstic zone, in which tiny conduits (cave passages too small to enter) are dissolved by the natural acidity of groundwater. The epikarstic zone concentrates local flows of runoff into high-elevation springs which emerge at the edges of ridges. The resurgent water from these springs typically flows briefly on the surface before sinking underground again at elevation of the contact between the sandstone caprock

Caprock or cap rock is a more resistant rock type overlying a less resistant rock type,Kearey, Philip (2001). ''Dictionary of Geology'', 2nd ed., Penguin Reference, London, New York, etc., p. 41.. . analogous to an upper crust on a cake that is ha ...

and the underlying massive limestones. It is in these underlying massive limestone layers that the human-explorable caves of the region have naturally developed.

The limestone layers of the

The limestone layers of the stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostra ...

column beneath the Big Clifty, in increasing order of depth below the ridgetops, are the Girkin Formation, the Ste. Genevieve Limestone, and the St. Louis Limestone

The St. Louis Limestone is a large geologic formation covering a wide area of the midwest of the United States. It is named after an exposure at St. Louis, Missouri. It consists of sedimentary limestone with scattered chert beds, including t ...

. For example, the large Main Cave passage seen on the Historic Tour is located at the bottom of the Girkin and the top of the Ste. Genevieve Formation.

Each of the primary layers of limestone is divided further into named geological units and sub-units. One area of cave research involves correlating the stratigraphy with the cave survey produced by explorers. This makes it possible to produce approximate three-dimensional maps of the contours of the various layer boundaries without the necessity for test wells and extracting core samples.

The upper sandstone caprock is relatively hard for water to penetrate: the exceptions are where vertical cracks occur. This protective role means that many of the older, upper passages of the cave system are very dry, with no stalactite

A stalactite (, ; from the Greek 'stalaktos' ('dripping') via

''stalassein'' ('to drip') is a mineral formation that hangs from the ceiling of caves, hot springs, or man-made structures such as bridges and mines. Any material that is soluble ...

s, stalagmite

A stalagmite (, ; from the Greek , from , "dropping, trickling")

is a type of rock formation that rises from the floor of a cave due to the accumulation of material deposited on the floor from ceiling drippings. Stalagmites are typicall ...

s, or other formations which require flowing or dripping water to develop.

However, the sandstone caprock layer has been dissolved and eroded at many locations within the park, such as the Frozen Niagara room. The contact between limestone and sandstone can be found by hiking from the valley bottoms to the ridgetops: typically, as one approaches the top of a ridge, one sees the outcrops of exposed rock change in composition from limestone to sandstone at a well-defined elevation.

At one valley bottom in the southern region of the park, a massive sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

has developed. Known as Cedar Sink, the sinkhole features a small river entering one side and disappearing back underground at the other side.

Visiting

The

The National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational properti ...

offers several cave tours to visitors. Some notable features of the cave, such as Grand Avenue, Frozen Niagara, and Fat Man's Misery, can be seen on lighted tours ranging from one to six hours in length. Two tours, lit only by visitor-carried paraffin lamps, are popular alternatives to the electric-lit routes. Several "wild" tours venture away from the developed parts of the cave into muddy crawls and dusty tunnels.

The Echo River Tour, one of the cave's most famous attractions, took visitors on a boat ride along an underground river. The tour was discontinued for logistic and environmental reasons in the early 1990s.

Mammoth Cave headquarters and visitor center is located on Mammoth Cave Parkway. The parkway connects with Kentucky Route 70

Kentucky Route 70 (KY 70) is a long east-east state highway that originates at a junction with U.S. Route 60 (US 60) in Smithland in Livingston County, just east of the Ohio River. The route continues through the counties of Crittend ...

from the north and Kentucky Route 255 from the south within the park.

History

Prehistory

The story of human beings in relation to Mammoth Cave spans five thousand years. Several sets of Native American remains have been recovered from Mammoth Cave, or other nearby caves in the region, in both the 19th and 20th centuries. Most

The story of human beings in relation to Mammoth Cave spans five thousand years. Several sets of Native American remains have been recovered from Mammoth Cave, or other nearby caves in the region, in both the 19th and 20th centuries. Most mummies

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay furt ...

found represent examples of intentional burial, with ample evidence of pre-Columbian

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, ...

funerary practice.

An exception to purposeful burial was discovered when in 1935 the remains of an adult male were discovered under a large boulder. The boulder had shifted and settled onto the victim, a pre-Columbian miner, who had disturbed the rubble supporting it. The remains of the ancient victim were named "Lost John" and exhibited to the public into the 1970s, when they were interred in a secret location in Mammoth Cave for reasons of preservation as well as emerging political sensitivities with respect to the public display of Native American remains.

Research beginning in the late 1950s led by Patty Jo Watson, of Washington University in St. Louis has done much to illuminate the lives of the late Archaic and early Woodland peoples who explored and exploited caves in the region. Preserved by the constant cave environment, dietary evidence yielded carbon dates enabling Watson and others to determine the age of the specimens. An analysis of their content, also pioneered by Watson, allows determination of the relative content of plant and meat in the diet of either culture over a period spanning several thousand years. This analysis indicates a timed transition from a hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

culture to plant domestication

Plant breeding started with sedentary agriculture, particularly the domestication of the first agricultural plants, a practice which is estimated to date back 9,000 to 11,000 years. Initially, early human farmers selected food plants with particula ...

and agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

.

Another technique employed in archaeological research, at Mammoth Cave, was "experimental archaeology

Experimental archaeology (also called experiment archaeology) is a field of study which attempts to generate and test archaeological hypotheses, usually by replicating or approximating the feasibility of ancient cultures performing various tasks ...

" in which modern explorers were sent into the cave using the same technology as that employed by the ancient cultures whose leftover implements lie discarded in many parts of the cave. The goal was to gain insight into the problems faced by the ancient people who explored the cave, by placing the researchers in a similar physical situation.

Ancient human remains and artifacts within the caves are protected by various federal and state laws. One of the most basic facts to be determined about a newly discovered artifact is its precise location and situation. Even slightly moving a prehistoric artifact contaminates it from a research perspective. Explorers are properly trained not to disturb archaeological evidence, and some areas of the cave remain out-of-bounds for even seasoned explorers, unless the subject of the trip is archaeological research on that area.

Besides the remains that have been discovered in the portion of the cave accessible through the Historic Entrance of Mammoth Cave, the remains of cane torches used by Native Americans, as well as other artifacts such as drawings, gourd fragments, and woven grass moccasin slippers are found in the Salts Cave section of the system in Flint Ridge.

Though there is undeniable proof of their existence and use of the cave, there is no evidence of further use past the archaic period. Experts and scientists have no answer as to why this is, making it one of the greatest mysteries of Mammoth Cave to this day.

Earliest written history

The tract known as the "Pollard Survey" was sold byindenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

on September 10, 1791 in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

by William Pollard. of the "Pollard Survey" between the North bank of Bacon Creek

Bacon Creek is a glacial stream in Whatcom County, Washington. It originates in a glacier on the southwest face of Bacon Peak, flows into a small tarn, then flows over the Berdeen Falls. At the base of the waterfall, the creek turns southeast and ...

and the Green River were purchased by Thomas Lang, Jr., a British American merchant from Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, England on June 3, 1796, for £4,116/13s/0d (£4,116.65). The land was lost to a local county tax claim during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

.

Legend has it that the first European to visit Mammoth Cave was either John Houchin or his brother Francis Houchin, in 1797. While hunting, Houchin pursued a wounded bear to the cave's large entrance opening near the Green River. Some Houchin Family tales have John Decatur "Johnny Dick" Houchin as the discoverer of the cave, but this is highly unlikely because Johnny Dick was only 10 years old in 1797 and was unlikely to be out hunting bears at such an age. His father John is the more likely candidate from that branch of the family tree, but the most probable candidate for discoverer of Mammoth Cave is Francis "Frank" Houchin, whose land was much closer to the cave entrance than his brother John's. There is also the argument that their brother Charles Houchin, who was known as a great hunter and trapper, was the man who shot that bear and chased it into the cave. The shadow over Charles's claim is the fact that he was residing in Illinois until 1801. Contrary to this story is Brucker and Watson's ''The Longest Cave'', which asserts that the cave was "certainly known before that time." Caves in the area were known before the discovery of the entrance to Mammoth Cave. Even Francis Houchin had a cave entrance on his land very near the bend in the Green River known as the Turnhole, which is less than a mile from the main entrance of Mammoth Cave.

The land containing this historic entrance was first surveyed and registered in 1798 under the name of Valentine Simons. Simons began exploiting Mammoth Cave for its

Legend has it that the first European to visit Mammoth Cave was either John Houchin or his brother Francis Houchin, in 1797. While hunting, Houchin pursued a wounded bear to the cave's large entrance opening near the Green River. Some Houchin Family tales have John Decatur "Johnny Dick" Houchin as the discoverer of the cave, but this is highly unlikely because Johnny Dick was only 10 years old in 1797 and was unlikely to be out hunting bears at such an age. His father John is the more likely candidate from that branch of the family tree, but the most probable candidate for discoverer of Mammoth Cave is Francis "Frank" Houchin, whose land was much closer to the cave entrance than his brother John's. There is also the argument that their brother Charles Houchin, who was known as a great hunter and trapper, was the man who shot that bear and chased it into the cave. The shadow over Charles's claim is the fact that he was residing in Illinois until 1801. Contrary to this story is Brucker and Watson's ''The Longest Cave'', which asserts that the cave was "certainly known before that time." Caves in the area were known before the discovery of the entrance to Mammoth Cave. Even Francis Houchin had a cave entrance on his land very near the bend in the Green River known as the Turnhole, which is less than a mile from the main entrance of Mammoth Cave.

The land containing this historic entrance was first surveyed and registered in 1798 under the name of Valentine Simons. Simons began exploiting Mammoth Cave for its saltpeter

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate Salt (chemistry), salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ...

reserves.

According to family records passed down through the Houchin, and later Henderson families, John Houchin was bear hunting and the bear turned and began to chase him. He found the cave entrance when he ran into the cave for protection from the charging bear.

19th century

In partnership with Valentine Simon, various other individuals would own the land through the

In partnership with Valentine Simon, various other individuals would own the land through the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, when Mammoth Cave's saltpeter reserves became significant due to the Jefferson Embargo Act of 1807 which prohibited all foreign trade. The blockade starved the American military of saltpeter and therefore gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

. As a result, the domestic price of saltpeter rose and production based on nitrates extracted from caves such as Mammoth Cave became more lucrative.

In July 1812, the cave was purchased from Simon and other owners by Charles Wilkins and an investor from Philadelphia named Hyman Gratz. Soon the cave was being mined for calcium nitrate on an industrial scale, utilizing a labor force of 70 slaves to build and operate the soil leaching apparatus, as well as to haul the raw soil from deep in the cave to the central processing site.

A half-interest in the cave changed hands for ten thousand dollars (equivalent to over $150,000 in 2020). After the war when prices fell, the workings were abandoned and it became a minor tourist attraction centering on a Native American mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay fu ...

discovered nearby.

When Wilkins died his estate's executors sold his interest in the cave to Gratz. In the spring of 1838, the cave was sold by the Gratz brothers to Franklin Gorin, who intended to operate Mammoth Cave purely as a tourist attraction, the bottom long having since fallen out of the saltpeter market. Gorin was a slave owner, and used his slaves as tour guides. Stephen Bishop was one of these slaves and would make a number of important contributions to human knowledge of the cave, becoming one of Mammoth Cave's most celebrated historical figures.

Stephen Bishop, an African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and a guide to the cave during the 1840s and 1850s, was one of the first people to make extensive map

A map is a symbolic depiction emphasizing relationships between elements of some space, such as objects, regions, or themes.

Many maps are static, fixed to paper or some other durable medium, while others are dynamic or interactive. Although ...

s of the cave, and named many of the cave's features.

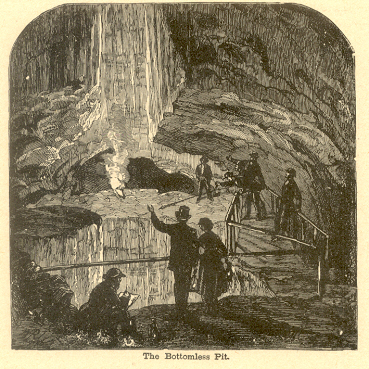

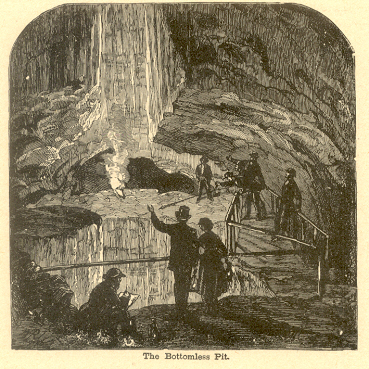

Stephen Bishop was introduced to Mammoth Cave in 1838 by Franklin Gorin. Gorin wrote, after Bishop's death: "I placed a guide in the cave – the celebrated and great Stephen, and he aided in making the discoveries. He was the first person who ever crossed the Bottomless Pit, and he, myself and another person whose name I have forgotten were the only persons ever at the bottom of Gorin's Dome to my knowledge."

"After Stephen crossed the Bottomless Pit, we discovered all that part of the cave now known beyond that point. Previous to those discoveries, all interest centered in what is known as the 'Old Cave' ... but now many of the points are but little known, although as Stephen was wont to say, they were 'grand, gloomy and peculiar'."

In 1839,

In 1839, John Croghan Dr. John Croghan (April 23, 1790 – January 11, 1849) was an American medical doctor and slave owner who helped establish the United States Marine Hospital of Louisville and organized some tuberculosis medical experiments and tours for Mammot ...

of Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

bought the Mammoth Cave Estate, including Bishop and its other slaves from their previous owner, Franklin Gorin. Croghan briefly ran an ill-fated tuberculosis hospital in the cave in 1842-43, the vapors of which he believed would cure his patients. A widespread epidemic of the period, tuberculosis would ultimately claim the life of Dr. Croghan in 1849.

In 1866 the first photos from within the Mammoth Cave were taken by Charles Waldack, a photographer from Cincinnati, Ohio, using a very dangerous method of flash photography called magnesium flash photography.

Throughout the 19th century, the fame of Mammoth Cave would grow so that the cave became an international sensation. At the same time, the cave attracted the attention of 19th century writers such as Robert Montgomery Bird

Robert Montgomery Bird (February 5, 1806 – January 23, 1854) was an American novelist, playwright, and physician.

Early life and education

Bird was born in New Castle, Delaware on February 5, 1806.Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. ''The Oxfor ...

, the Rev. Robert Davidson, the Rev. Horace Martin, Alexander Clark Bullitt, Nathaniel Parker Willis (who visited in June 1852), Bayard Taylor

Bayard Taylor (January 11, 1825December 19, 1878) was an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author, and diplomat. As a poet, he was very popular, with a crowd of more than 4,000 attending a poetry reading once, which was a record ...

(in May 1855), William Stump Forwood (in spring 1867), the naturalist John Muir

John Muir ( ; April 21, 1838December 24, 1914), also known as "John of the Mountains" and "Father of the National Parks", was an influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher, botanist, zoologist, glaciologis ...

(early September 1867), the Rev. Horace Carter Hovey, and others. As a result of the growing renown of Mammoth Cave, the cave boasted famous visitors such as actor Edwin Booth

Edwin Thomas Booth (November 13, 1833 – June 7, 1893) was an American actor who toured throughout the United States and the major capitals of Europe, performing Shakespearean plays. In 1869, he founded Booth's Theatre in New York. Some theatric ...

(his brother, John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth ...

, assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

in 1865), singer Jenny Lind

Johanna Maria "Jenny" Lind (6 October 18202 November 1887) was a Swedish opera singer, often called the "Swedish Nightingale". One of the most highly regarded singers of the 19th century, she performed in soprano roles in opera in Sweden and ...

(who visited the cave on April 5, 1851), and violinist Ole Bull

Ole Bornemann Bull (; 5 February 181017 August 1880) was a Norwegian virtuoso violinist and composer. According to Robert Schumann, he was on a level with Niccolò Paganini for the speed and clarity of his playing.

Biography

Background

Bull ...

who together gave a concert in one of the caves. Two chambers in the caves have since been known as "Booth's Amphitheatre" and "Ole Bull's Concert Hall".

Early 20th century: The Kentucky Cave Wars

The difficulties of farming life in the hardscrabble, poor soil of the cave-country influenced local owners of smaller nearby caves to see opportunities for commercial exploitation, particularly given the success of Mammoth Cave as a tourist attraction. The "Kentucky Cave Wars" was a period of bitter competition between local cave owners for tourist money. Broad tactics of deception were used to lure visitors away from their intended destination to other private show caves. Misleading signs were placed along the roads leading to the Mammoth Cave. A typical strategy during the early days of automobile travel involved representatives (known as "cappers") of other private show caves hopping aboard a tourist's car's running board, and leading the passengers to believe that Mammoth Cave was closed, quarantined, caved in or otherwise inaccessible.

In 1906, Mammoth Cave became accessible by

The difficulties of farming life in the hardscrabble, poor soil of the cave-country influenced local owners of smaller nearby caves to see opportunities for commercial exploitation, particularly given the success of Mammoth Cave as a tourist attraction. The "Kentucky Cave Wars" was a period of bitter competition between local cave owners for tourist money. Broad tactics of deception were used to lure visitors away from their intended destination to other private show caves. Misleading signs were placed along the roads leading to the Mammoth Cave. A typical strategy during the early days of automobile travel involved representatives (known as "cappers") of other private show caves hopping aboard a tourist's car's running board, and leading the passengers to believe that Mammoth Cave was closed, quarantined, caved in or otherwise inaccessible.

In 1906, Mammoth Cave became accessible by steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

with the construction of a lock and dam at Brownsville, Kentucky

Brownsville is a home rule-class city in Edmonson County, Kentucky, in the United States. It is the county seat and is a certified Kentucky Trail Town. The population was 836 at the time of the 2010 census, down from 921 at the 2000 census. It ...

.

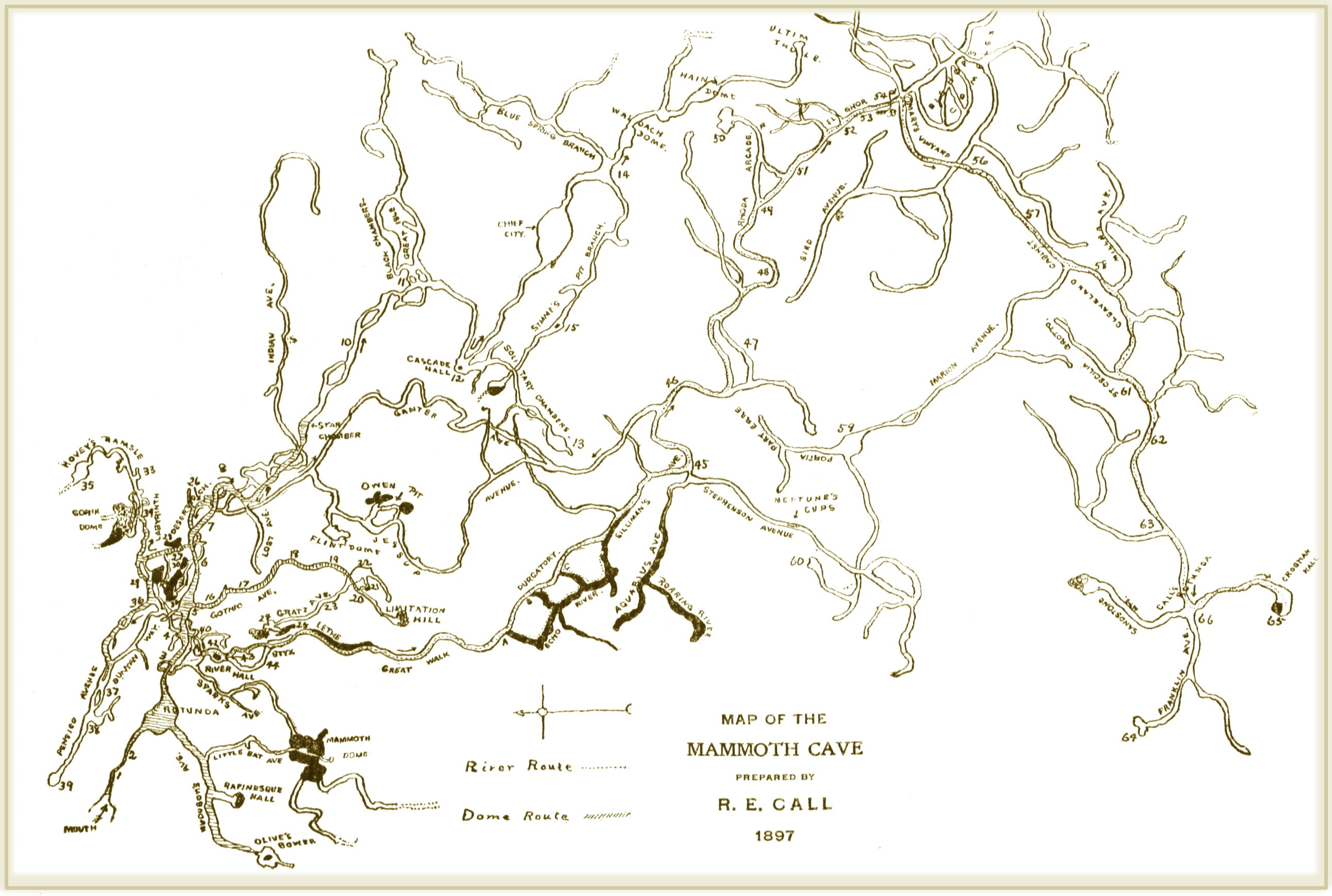

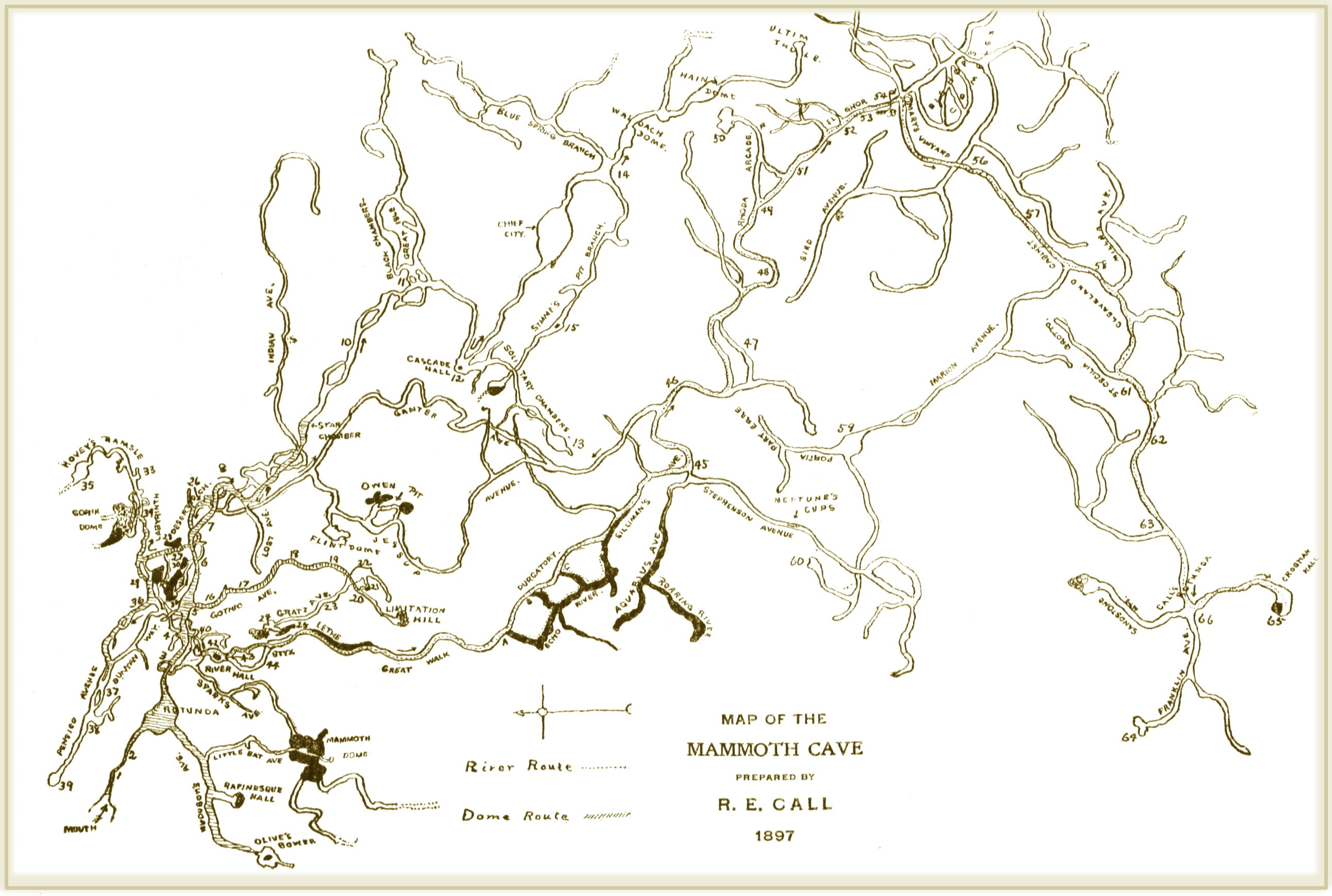

In 1908, Max Kämper, a young German mining engineer, arrived at the cave by way of New York. Kämper had just graduated from technical college and his family had sent him on a trip abroad as a graduation present. Originally intending to spend two weeks at Mammoth Cave, Kämper spent several months. With the assistance of Ed Bishop, a Mammoth Cave Guide, Kämper produced a remarkably accurate instrumental survey of many kilometers of Mammoth Cave, including many new discoveries. Reportedly, Kämper also produced a corresponding survey of the land surface overlying the cave: this information was to be useful in the opening of other entrances to the cave, as soon happened with the Violet City entrance.

The Croghan family suppressed the topographic element of Kämper's map, and it is not known to survive today, although the cave map portion of Kämper's work stands as a triumph of accurate cave cartography: not until the early 1960s and the advent of the modern exploration period would these passages be surveyed and mapped with greater accuracy. Kämper returned to Berlin, and from the point of view of the Mammoth Cave country, disappeared entirely. It was not until the turn of the 21st century that a group of German tourists, after visiting the cave, researched Kämper's family and determined his fate: the young Kämper was killed in trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artille ...

in World War I at the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place be ...

December 10, 1916.

Famed French cave explorer

Famed French cave explorer Édouard-Alfred Martel

Édouard-Alfred Martel (1 July 1859, Pontoise, Val-d'Oise – 3 June 1938, Montbrison), the 'father of modern speleology', was a world pioneer of cave exploration, study, and documentation. Martel explored thousands of caves in his native Fra ...

visited the cave for three days in October 1912. Without access to the closely held survey data, Martel was permitted to make barometric observations in the cave for the purpose of determining the relative elevation of different locations in the cave. He identified different levels of the cave and correctly noted that the level of the Echo River within the cave was controlled by that of the Green River on the surface. Martel lamented the 1906 construction of the dam at Brownsville, pointing out that this made a full hydrologic study of the cave impossible. Among his precise descriptions of the hydrogeologic setting of Mammoth Cave, Martel offered the speculative conclusion that Mammoth Cave was connected to Salts and Colossal Caves: this would not be proven correct until 60 years after Martel's visit.

In the early 1920s, George Morrison created, via blasting, a number of entrances to Mammoth Cave on land not owned by the Croghan Estate. Absent the data from the Croghan's secretive surveys, performed by Kämper, Bishop, and others, which had not been published in a form suitable for determining the geographic extent of the cave, it was now conclusively shown that the Croghans had been for years exhibiting portions of Mammoth Cave which were not under land they owned. Lawsuits were filed and, for a time, different entrances to the cave were operated in direct competition with each other.

In the early 20th century, Floyd Collins spent ten years exploring the Flint Ridge Cave System (the most important legacy of these explorations was the discovery of Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave and exploration in Salts Cave) before dying at Sand Cave, Kentucky, in 1925. While exploring Sand Cave, he dislodged a rock onto his leg while in a tight crawlway and was unable to be rescued before dying of starvation. Attempts to rescue Collins created a mass media sensation; the resulting publicity would draw prominent Kentuckians to initiate a movement which would soon result in the formation of Mammoth Cave National Park.

The national park movement (1926–1941)

As the last of the Croghan heirs died, advocacy momentum grew among wealthy citizens of Kentucky for the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. Private citizens formed the Mammoth Cave National Park Association in 1924. The park was authorized May 25, 1926.

Donated funds were used to purchase some farmsteads in the region, while other tracts within the proposed national park boundary were acquired by right of

As the last of the Croghan heirs died, advocacy momentum grew among wealthy citizens of Kentucky for the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. Private citizens formed the Mammoth Cave National Park Association in 1924. The park was authorized May 25, 1926.

Donated funds were used to purchase some farmsteads in the region, while other tracts within the proposed national park boundary were acquired by right of eminent domain

Eminent domain (United States, Philippines), land acquisition (India, Malaysia, Singapore), compulsory purchase/acquisition (Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, United Kingdom), resumption (Hong Kong, Uganda), resumption/compulsory acquisition (Austr ...

. In contrast to the formation of other national parks in the sparsely populated American West, thousands of people would be forcibly relocated in the process of forming Mammoth Cave National Park. Often eminent domain proceedings were bitter, with landowners paid what were considered to be inadequate sums. The resulting acrimony still resonates within the region.

For legal reasons, the federal government was prohibited from restoring or developing the cleared farmsteads while the private Association held the land: this regulation was evaded by the operation of "a maximum of four" CCC camps from May 22, 1933 to July 1942.

According to the National Park Service, "By May 22, 1936, 27,402 acres of land had been acquired and accepted by the Secretary of the Interior. The area was declared a national park on July 1, 1941 when the minimum of 45,310 acres (over 600 parcels) had been assembled."

Superintendent Hoskins later wrote of a summer tanager named Pete who arrived at the guide house on or around every April 20, starting in 1938. The bird ate from food held in the hands of the guides, to the delight of visitors, and provided food to his less-tame mate.

Birth of the national park (1941)

Mammoth Cave National Park was officially dedicated on July 1, 1941. By coincidence, the same year saw the incorporation of the

Mammoth Cave National Park was officially dedicated on July 1, 1941. By coincidence, the same year saw the incorporation of the National Speleological Society

The National Speleological Society (NSS) is an organization formed in 1941 to advance the exploration, conservation, study, and understanding of caves in the United States. Originally headquartered in Washington D.C., its current offices are in ...

. R. Taylor Hoskins, the second Acting Superintendent under the old Association, became the first official Superintendent, a position he held until 1951.

The New Entrance, closed to visitors since 1941, was reopened on December 26, 1951, becoming the entrance used for the beginning of the Frozen Niagara tour.

The longest cave (1954–1972)

By 1954, Mammoth Cave National Park's land holdings encompassed all lands within its outer boundary with the exception of two privately held tracts. One of these, the old Lee Collins farm, had been sold to Harry Thomas of Horse Cave, Kentucky, whose grandson, William "Bill" Austin, operated Collins Crystal Cave as a show cave in direct competition with the national park, which was forced to maintain roads leading to the property.

In February 1954, a two-week expedition under the auspices of the

By 1954, Mammoth Cave National Park's land holdings encompassed all lands within its outer boundary with the exception of two privately held tracts. One of these, the old Lee Collins farm, had been sold to Harry Thomas of Horse Cave, Kentucky, whose grandson, William "Bill" Austin, operated Collins Crystal Cave as a show cave in direct competition with the national park, which was forced to maintain roads leading to the property.

In February 1954, a two-week expedition under the auspices of the National Speleological Society

The National Speleological Society (NSS) is an organization formed in 1941 to advance the exploration, conservation, study, and understanding of caves in the United States. Originally headquartered in Washington D.C., its current offices are in ...

was organized at the invitation of Austin: this expedition became known as C-3, or the Collins Crystal Cave Expedition.

The C-3 expedition drew public interest, first from a photo essay published by Robert Halmi in the July 1954 issue of True Magazine and later from the publication of a double first-person account of the expedition, ''The Caves Beyond: The Story of the Collins Crystal Cave Expedition'' by Joe Lawrence, Jr. (then president of the National Speleological Society) and Roger Brucker

Roger W. Brucker (born July 27, 1929) is an American cave explorer and author of books about caves. He is most closely associated with Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, the world's longest cave, which he has been exploring and writing about since 1954. ...

. The expedition proved conclusively that passages in Crystal Cave extended toward Mammoth Cave proper, at least exceeding the Crystal Cave property boundaries. However, this information was closely held by the explorers: it was feared that the National Park Service might forbid exploration were this known.

In 1955 Crystal Cave was connected by survey with Unknown Cave, the first connection in the Flint Ridge system.

Some of the participants in the C-3 expedition wished to continue their explorations past the conclusion of the C-3 Expedition, and organized as the Flint Ridge Reconnaissance under the guidance of Austin, Jim Dyer, John J. Lehrberger and E. Robert Pohl. This organization was incorporated in 1957 as the Cave Research Foundation. The organization sought to legitimize the cave explorers' activity through the support of original academic and scientific research. Notable scientists who studied Mammoth Cave during this period include Patty Jo Watson (see section on prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

).

In March 1961, the Crystal Cave property was sold to the National Park Service for $285,000. At the same time, the Great Onyx Cave

Great Onyx Cave is a cave located in Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, United States. The National Park Service offers a commercial tour of the cave.

Discovery

Great Onyx Cave was discovered in 1915 by Edmund Turner. According to one st ...

property, the only other remaining private inholding

An inholding is privately owned land inside the boundary of a national park, national forest, state park, or similar publicly owned, protected area. In-holdings result from private ownership of lands predating the designation of the park or fores ...

, was purchased for $365,000. The Cave Research Foundation was permitted to continue their exploration through a Memorandum of Understanding with the National Park Service.

Colossal Cave was connected by survey to Salts Cave in 1960 and in 1961 Colossal-Salts cave was similarly connected to Crystal-Unknown cave, creating a single cave system under much of Flint Ridge. By 1972, the Flint Ridge Cave System had been surveyed to a length of , making it the longest cave in the world.

Flint–Mammoth connection (1972)

During the 1960s, Cave Research Foundation (CRF) exploration and mapping teams had found passageways in the Flint Ridge Cave System that penetrated under Houchins Valley and came within of known passages in Mammoth Cave. In 1972, CRF Chief Cartographer John Wilcox pursued an aggressive program to finally connect the caves, fielding several expeditions from the Flint Ridge side as well as exploring leads in Mammoth Cave.

On a July 1972 trip, deep in the Flint Ridge Cave System, Patricia Crowther—with her slight frame of —crawled through a narrow canyon later dubbed the "Tight Spot", which acted as a filter for larger cavers. A subsequent trip past the Tight Spot on August 30, 1972, by Wilcox, Crowther, Richard Zopf, and Tom Brucker discovered the name "Pete H" inscribed on the wall of a river passage with an arrow pointing in the direction of Mammoth Cave. The name is believed to have been carved by Warner P. "Pete" Hanson, who was active in exploring the cave in the 1930s. Hanson had been killed in

During the 1960s, Cave Research Foundation (CRF) exploration and mapping teams had found passageways in the Flint Ridge Cave System that penetrated under Houchins Valley and came within of known passages in Mammoth Cave. In 1972, CRF Chief Cartographer John Wilcox pursued an aggressive program to finally connect the caves, fielding several expeditions from the Flint Ridge side as well as exploring leads in Mammoth Cave.

On a July 1972 trip, deep in the Flint Ridge Cave System, Patricia Crowther—with her slight frame of —crawled through a narrow canyon later dubbed the "Tight Spot", which acted as a filter for larger cavers. A subsequent trip past the Tight Spot on August 30, 1972, by Wilcox, Crowther, Richard Zopf, and Tom Brucker discovered the name "Pete H" inscribed on the wall of a river passage with an arrow pointing in the direction of Mammoth Cave. The name is believed to have been carved by Warner P. "Pete" Hanson, who was active in exploring the cave in the 1930s. Hanson had been killed in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The passage was named Hanson's Lost River by the explorers.

Finally, on September 9, 1972, a six-person CRF team of Wilcox, Crowther, Zopf, Gary Eller, Stephen Wells, and Cleveland Pinnix (a National Park Service ranger) followed Hanson's Lost River downstream to discover its connection with Echo River in Cascade Hall of Mammoth Cave. With this linking of the Flint Ridge and Mammoth Cave systems, the "Everest of speleology" had been climbed. The integrated cave system contained of surveyed passages and had fourteen entrances.

Recent discoveries

Further connections between Mammoth Cave and smaller caves or cave systems have followed, notably to Proctor/Morrison Cave beneath nearby Joppa Ridge in 1979. Proctor Cave was discovered by Jonathan Doyle, a Union Army deserter during the Civil War, and was later owned by the Mammoth Cave Railroad, before being explored by the CRF. Morrison cave was discovered by George Morrison in the 1920s. This connection pushed the frontier of Mammoth exploration southeastward.

At the same time, discoveries made outside the park by an independent group called the Central Kentucky Karst Coalition or CKKC resulted in the survey of tens of miles in Roppel Cave east of the park. Discovered in 1976, Roppel Cave was briefly on the list of the nation's longest caves before it was connected to the Proctor/Morrison's section of the Mammoth Cave System on September 10, 1983. The connection was made by two mixed parties of CRF and CKKC explorers. Each party entered through a separate entrance and met in the middle before continuing in the same direction to exit at the opposite entrance. The resulting total surveyed length was near .

On March 19, 2005, a connection into the Roppel Cave portion of the system was surveyed from a small cave under Eudora Ridge, adding approximately three miles to the known length of the Mammoth Cave System. The newly found entrance to the cave, now termed the "Hoover Entrance", had been discovered in September 2003, by Alan Canon and James Wells. Incremental discoveries since then have pushed the total to more than .

It is certain that many more miles of cave passages await discovery in the region. Discovery of new natural entrances is a rare event: the primary mode of discovery involves the pursuit of side passages identified during routine systematic exploration of cave passages entered from known entrances.

Further connections between Mammoth Cave and smaller caves or cave systems have followed, notably to Proctor/Morrison Cave beneath nearby Joppa Ridge in 1979. Proctor Cave was discovered by Jonathan Doyle, a Union Army deserter during the Civil War, and was later owned by the Mammoth Cave Railroad, before being explored by the CRF. Morrison cave was discovered by George Morrison in the 1920s. This connection pushed the frontier of Mammoth exploration southeastward.

At the same time, discoveries made outside the park by an independent group called the Central Kentucky Karst Coalition or CKKC resulted in the survey of tens of miles in Roppel Cave east of the park. Discovered in 1976, Roppel Cave was briefly on the list of the nation's longest caves before it was connected to the Proctor/Morrison's section of the Mammoth Cave System on September 10, 1983. The connection was made by two mixed parties of CRF and CKKC explorers. Each party entered through a separate entrance and met in the middle before continuing in the same direction to exit at the opposite entrance. The resulting total surveyed length was near .

On March 19, 2005, a connection into the Roppel Cave portion of the system was surveyed from a small cave under Eudora Ridge, adding approximately three miles to the known length of the Mammoth Cave System. The newly found entrance to the cave, now termed the "Hoover Entrance", had been discovered in September 2003, by Alan Canon and James Wells. Incremental discoveries since then have pushed the total to more than .

It is certain that many more miles of cave passages await discovery in the region. Discovery of new natural entrances is a rare event: the primary mode of discovery involves the pursuit of side passages identified during routine systematic exploration of cave passages entered from known entrances.

Related and nearby caves

At least two other massive cave systems lie short distances from Mammoth Cave: theFisher Ridge Cave System

The Fisher Ridge Cave System is a cave system located in Hart County, Kentucky, United States, near Mammoth Cave National Park. As of November 2019 it had been mapped to a length of , making it the fifth-longest cave in the United States and th ...

and the Martin Ridge Cave System. The Fisher Ridge Cave System was discovered in January 1981 by a group of Michigan cavers associated with the Detroit Urban Grotto of the National Speleological Society

The National Speleological Society (NSS) is an organization formed in 1941 to advance the exploration, conservation, study, and understanding of caves in the United States. Originally headquartered in Washington D.C., its current offices are in ...

. So far, the Fisher Ridge Cave System has been mapped to . In 1976, Rick Schwartz discovered a large cave south of the Mammoth Cave park boundary. This cave became known as the Martin Ridge Cave System in 1996, as new exploration connected the 3 nearby caves of Whigpistle Cave (Schwartz's original entrance), Martin Ridge Cave, and Jackpot Cave. As of 2018, the Martin Ridge Cave System had been mapped to a length of , and exploration continued.

Climate

According to theKöppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, nota ...

system, Mammoth Cave National Park has a Humid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

(''Cfa''). According to the United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of comme ...

, the Plant Hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

at Mammoth Cave National Park Visitor Center at 722 ft (220 m) elevation is 6b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -3.2 °F (-19.6 °C).

Biology and ecosystem

The following species of bats inhabit the caverns:Indiana bat

The Indiana bat (''Myotis sodalis'') is a medium-sized mouse-eared bat native to North America. It lives primarily in Southern and Midwestern U.S. states and is listed as an endangered species. The Indiana bat is grey, black, or chestnut in colo ...

(''Myotis sodalis''), gray bat (''Myotis grisescens''), little brown bat (''Myotis lucifugus''), big brown bat (''Eptesicus fuscus''), and the eastern pipistrelle

The tricolored bat (''Perimyotis subflavus'') is a species of microbat native to eastern North America. Formerly known as the eastern pipistrelle, based on the incorrect belief that it was closely related to European ''Pipistrellus'' species, th ...

bat (''Pipistrellus subflavus'').

All together, these and more rare bat species such as the eastern small-footed bat had estimated populations of 9–12 million just in the Historic Section. While these species still exist in Mammoth Cave, their numbers are now no more than a few thousand at best. Ecological restoration of this portion of Mammoth Cave, and facilitating the return of bats, is an ongoing effort. Not all bat species here inhabit the cave; the red bat ('' Lasiurus borealis'') is a forest-dweller, as found underground only rarely.

Other animals which inhabit the caves include:

two genera of crickets ('' Hadenoecus subterraneus'') and ('' Ceuthophilus stygius'') ('' Ceuthophilus latens''), a cave salamander

A cave salamander is a type of salamander that primarily or exclusively inhabits caves, a group that includes several species. Some of these animals have developed special, even extreme, adaptations to their subterranean environments. Some speci ...

(''Eurycea lucifuga

The spotted-tail salamander (''Eurycea lucifuga''), also known as a "cave salamander", is a species of brook salamander.

Description

The spotted-tail salamander is a relatively large lungless salamander, ranging in total length from 10 to 20&nb ...

''), two genera of eyeless cave fish

Cavefish or cave fish is a generic term for fresh and brackish water fish adapted to life in caves and other underground habitats. Related terms are subterranean fish, troglomorphic fish, troglobitic fish, stygobitic fish, phreatic fish and ...

(''Typhlichthys subterraneus

''Typhlichthys subterraneus'', the southern cavefish, is a species of cavefish in the family Amblyopsidae endemic to karst regions of the eastern United States.

Taxonomy

''T. subterraneus'' is a one of five obligate troglobitic species in Ambl ...

'') and (''Amblyopsis spelaea

The northern cavefish or northern blindfish (''Amblyopsis spelaea'') is found in caves through Kentucky and southern Indiana. It is listed as a threatened species in the United States and the IUCN lists the species as near threatened.

During ...

''), a cave crayfish ('' Orconectes pellucidus''), and a cave shrimp (''Palaemonias ganteri

The Kentucky cave shrimp (''Palaemonias ganteri'') is an eyeless, troglobite shrimp. It lives in caves in Barren County, Edmonson County, Hart County and Warren County, Kentucky. The shrimp's shell has no pigment; the species is nearly transpa ...

'').

In addition, some surface animals may take refuge in the entrances of the caves but do not generally venture into the deep portions of the cavern system.

The section of the Green River that flows through the park is legally designated as "Kentucky Wild River" by the Kentucky General Assembly, through the Office of Kentucky Nature Preserves' Wild Rivers Program.

According to the A. W. Kuchler August William Kuchler (born ''August Wilhelm Küchler''; 1907–1999) was a German-born American geographer and naturalist who is noted for developing a plant association system in widespread use in the United States. Some of this database has bec ...

U.S. Potential natural vegetation

In ecology, potential natural vegetation (PNV), also known as Kuchler potential vegetation, is the vegetation that would be expected given environmental constraints (climate, geomorphology, geology) without human intervention or a hazard event ...

Types, Mammoth Cave National Park has an Oak/Hickory

Hickory is a common name for trees composing the genus ''Carya'', which includes around 18 species. Five or six species are native to China, Indochina, and India (Assam), as many as twelve are native to the United States, four are found in Mex ...

(''100'') potential vegetation type with an Eastern Hardwood Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest

Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest is a temperate climate terrestrial habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature, with broadleaf tree ecoregions, and with conifer and broadleaf tree mixed coniferous forest ecoregions.

These ...

(''25'') potential vegetation form.

Common fossils of the cave include crinoid

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

s, blastoid

Blastoids (class Blastoidea) are an extinct type of stemmed echinoderm, often referred to as sea buds. They first appear, along with many other echinoderm classes, in the Ordovician period, and reached their greatest diversity in the Mississi ...

s, and gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

s. The Mississippian limestone has yielded fossils of more than a dozen species of shark. In 2020, scientists reported the discovery of part of a '' Saivodus striatus'', a species comparable in size to a modern great white shark.

Name

The cave's name refers to the large width and length of the passages connecting to the Rotunda just inside the entrance. The name was used long before the extensive cave system was more fully explored and mapped, to reveal a mammoth length of passageways. No fossils of thewoolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with '' Mammuthus s ...

have ever been found in Mammoth Cave, and the name of the cave has nothing to do with this extinct mammal.

Cultural references

*A significant amount of the work of American poet Donald Finkel stems from his experiences caving in Mammoth Cave National Park. Examples include "Answer Back" from 1968, and the book-length ''Going Under'', published in 1978. *The layout for one of the earliest computer games, Will Crowther's 1976 ''Colossal Cave Adventure

''Colossal Cave Adventure'' (also known as ''Adventure'' or ''ADVENT'') is a text-based adventure game, released in 1976 by developer Will Crowther for the PDP-10 mainframe computer. It was expanded upon in 1977 by Don Woods. In the game, the ...

'', was based partly on the Mammoth Cave system.

*The video game ''Kentucky Route Zero

''Kentucky Route Zero'' is a point-and-click adventure game developed by Cardboard Computer and published by Annapurna Interactive. The game was first revealed in 2011 via the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter and is separated into five acts th ...

'' has a standalone expansion, set between its Acts III and IV, called ''Here And There Along The Echo'', which is a fictionalized hotline number providing information about the Echo River for "drifters" and "pilgrims". The game's third act itself also partially takes place within the Mammoth Cave system, and has references to ''Colossal Cave Adventure''.

*H. P. Lovecraft's 1918 short story " The Beast in the Cave" is set in "the Mammoth Cave".

*American rock band Guided by Voices referenced the cave in the 1990 song "Mammoth Cave" from their album '' Same Place the Fly Got Smashed''.

*The "Kentucky Mammoth Cave" is used as a metaphor for a sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

's stomach in chapter 75 of Herman Melville

Herman Melville ( born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. Among his best-known works are '' Moby-Dick'' (1851); '' Typee'' (1846), a ...

's 1851 novel ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

''.

*Fiction writer Lillie Devereux Blake

Lillie Devereux Blake (pen name, Tiger Lily; August 12, 1833 – December 30, 1913) was an American woman suffragist, reformer, and writer, born in Raleigh, North Carolina, and educated in New Haven, Connecticut. In her early years, Blake wrote se ...

writing for ''The Knickerbocker

''The Knickerbocker'', or ''New-York Monthly Magazine'', was a literary magazine of New York City, founded by Charles Fenno Hoffman in 1833, and published until 1865. Its long-term editor and publisher was Lewis Gaylord Clark, whose "Editor's ...

'' magazine in 1858 told a fictional story of a woman, Melissa, who murdered her tutor who did not return her love, by abandoning him in the cave without a lamp. According to the story, Melissa goes back into the cave fifteen years later to end her misery. Researcher Joe Nickell

Joe Nickell (born December 1, 1944) is an American skeptic and investigator of the paranormal.

Nickell is senior research fellow for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and writes regularly for their journal, ''Skeptical Inquirer''. He is also ...

writing for ''Skeptical Inquirer

''Skeptical Inquirer'' is a bimonthly American general-audience magazine published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI) with the subtitle: ''The Magazine for Science and Reason''.

Mission statement and goals

Daniel Loxton, writing in 2 ...

'' magazine explains that this gives "Credulous believers in ghosts... confirmation of their superstitious beliefs" who tell of hearing Melissa weeping and calling out for her murdered tutor. Nickell states that it is common to hear sounds in caves which "the brain interprets (as words and weeping)... it's called pareidolia

Pareidolia (; ) is the tendency for perception to impose a meaningful interpretation on a nebulous stimulus, usually visual, so that one sees an object, pattern, or meaning where there is none.

Common examples are perceived images of animals, ...

". Melissa is pure fiction, but author Blake did visit Mammoth Cave with her husband Frank Umsted, "traveling by train, steamer, and stagecoach".

Park superintendents