Madison Grant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a

He was also a developer of

He was also a developer of

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

At the postwar

At the postwar

''The Caribou.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902. * "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903.

''The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904. *

The Rocky Mountain Goat.

' Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905.

''The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. *

New ed.

rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918 *

Rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921. *

Fourth rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936. *

Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California

'' New York: Zoological Society, 1919.Reprinted i

''The National Geographic''

Vol. XXXVII, January/June, 1920.

''Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana.''

Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919.

''The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America''

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

"The Depletion of American Forests"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894. * "The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks", ''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVII, 1894.

"A Canadian Moose Hunt"

In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), ''Hunting in Many Lands.'' New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895.

"The Future of Our Fauna"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', No. 34, June 1909.

"History of the Zoological Society"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910.

"Condition of Wild Life in Alaska"

In: ''Hunting at High Altitudes.'' New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913.

"Wild Life Protection"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916.

"The Passing of the Great Race"

''Geographical Review'', Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916.

"The Physical Basis of Race"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. III, January 1917.

"Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity"

''The Journal of Heredity'', Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919.

"Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. VII, August 1921. * "Racial Transformation of America", ''The North American Review'', March 1924. * "America for the Americans", ''The Forum'', September 1925.

"Grant, Madison"

''American National Biography''. Oxford University Press. Online. * Degler, Carl N. (1991). ''In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought''. Oxford University Press. * Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 38 (3), pp. 523–540. * Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). ''The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.1 (2020): 3-18. * Leonard, Thomas C. ''Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era'' (Princeton UP, 2016) * Leonard, Thomas C. " 'More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era." ''History of Political Economy// 35.4 (2003): 687-712

online

* Marcus, Alan P. "The Dangers of the Geographical Imagination in the US Eugenics Movement." ''Geographical Review'' 111.1 (2021): 36-56. * Purdy, Jedediah (2015)

"Environmentalism's Racist History"

''

excerpt

* Spiro, Jonathan P. "Nordic vs. Anti-Nordic: The Galton Society and the American Anthropological Association", ''Patterns of Prejudice'' 36#1 (2002): 35–48. * Regal, Brian (2002). ''Henry Fairfield Osborn: Race and the Search for the Origins of Man''. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. * Regal, Brian (2004). "Maxwell Perkins and Madison Grant: Eugenics Publishing at Scribners", ''Princeton University Library Chronicle'' 65#2, pp. 317–341.

Excerpts from ''Passing of the Great Race'' used at the Nuremberg Trials

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Grant, Madison 1865 births 1937 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American writers 20th-century American anthropologists Amateur anthropologists American eugenicists American conservationists American conspiracy theorists American hunters American nationalists American people of English descent American people of French descent American political writers American white supremacists American zoologists Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Columbia Law School alumni Deaths from nephritis Lawyers from New York City Nordicism Philanthropists from New York (state) Race and intelligence controversy Proponents of scientific racism Writers from New York City Yale University alumni

eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching deeds in conservation than for his advocacy of Nordicism

Nordicism is an ideology of racism which views the historical race concept of the " Nordic race" as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and seminal Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book '' The Passing of the Great Ra ...

, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming tha ...

" as superior.

As a eugenicist, Grant was the author of ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, self-styled anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics, Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theo ...

'' (1916), one of the most famous racist texts, and played an active role in crafting immigration restriction and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) were laws passed by most states that prohibited interracial marriage, and in some cases also prohibited interracial sexual relations. Some such laws predate the e ...

. As a conservationist, he is credited with the saving of species including the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the ...

, helped create the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and is the largest metropolitan zoo in ...

, Glacier National Park, and Denali National Park

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is an American national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali, the highest mountain in North America. The park and contiguous preserve ...

, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League

Save the Redwoods League is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to protect and restore coast redwood (''Sequoia sempervirens'') and giant sequoia (''Sequoiadendron giganteum'') trees through the preemptive purchase of development rights ...

. Grant developed much of the discipline of wildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. It attempts to balance the needs of wildlife with the needs of people using the best availabl ...

.

Early life

Grant was born in New York City, New York, the son ofGabriel Grant

Dr. Gabriel Grant (September 4, 1826, Newark, New Jersey – November 8, 1909, Manhattan, New York ) was an American doctor and Union Army major who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at the American Civil War Battle of Fair Oaks. ...

, a physician and American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

surgeon, and Caroline Manice. Madison Grant's mother was a descendant of Jessé de Forest Jessé de Forest (1576 – October 22, 1624) was the leader of a group of Walloon Huguenots who fled Europe due to religious persecutions. They emigrated to the New World, where he planned to found New-Amsterdam, which is currently New York Ci ...

, the Walloon Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

who in 1623 recruited the first band of colonists to settle in New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva ...

, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

's territory on the American East Coast. On his father's side, Madison Grant's first American ancestor was Richard Treat, dean of Pitminster Church in England, who in 1630 was one of the first Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

settlers of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. Grant's forebears through Treat's line include Robert Treat

Robert Treat (February 23, 1624July 12, 1710) was a New England Puritan colonial leader, militia officer and governor of the Connecticut Colony between 1683 and 1698. In 1666 he helped found Newark, New Jersey.

Biography

Treat was born in Pitm ...

(a colonial governor of New Jersey), Robert Treat Paine

Robert Treat Paine (March 11, 1731 – May 11, 1814) was an American lawyer, politician and Founding Father of the United States who signed the Continental Association and the Declaration of Independence as a representative of Massachusetts. ...

(a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

), Charles Grant (Madison Grant's grandfather, who served as an officer in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

), and Gabriel Grant

Dr. Gabriel Grant (September 4, 1826, Newark, New Jersey – November 8, 1909, Manhattan, New York ) was an American doctor and Union Army major who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at the American Civil War Battle of Fair Oaks. ...

(father of Madison), a prominent physician and the health commissioner of Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat, seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County and the second largest city within the New Yo ...

. Grant was a lifelong resident of New York City.

Grant was the oldest of four siblings. The children's summers, and many of their weekends, were spent at Oatlands, the Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

country estate built by their grandfather DeForest Manice in the 1830s. As a child, he attended private schools and traveled Europe and the Middle East with his father. He attended Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

, graduating early and with honors in 1887. He received a law degree from Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (Columbia Law or CLS) is the law school of Columbia University, a private Ivy League university in New York City. Columbia Law is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious law schools in the world and has always ranked i ...

, and practiced law after graduation; however, his interests were primarily those of a naturalist. He never married and had no children. He first achieved a political reputation when he and his brother, De Forest Grant, took part in the 1894 electoral campaign of New York mayor William Lafayette Strong.

Conservation efforts

Thomas C. Leonard wrote that "Grant was a cofounder of the American environmental movement, a crusading conservationist who preserved the California redwoods; saved the American bison from extinction; fought for stricter gun control laws; helped create Glacier and Denali national parks; and worked to preserve whales, bald eagles, and pronghorn antelopes." Grant was a friend of several U.S. presidents, includingTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gre ...

. He is credited with saving many natural species from extinction, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League

Save the Redwoods League is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to protect and restore coast redwood (''Sequoia sempervirens'') and giant sequoia (''Sequoiadendron giganteum'') trees through the preemptive purchase of development rights ...

with Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to the British Army in colonial Africa, and for teach ...

, John C. Merriam

John Campbell Merriam (October 20, 1869 – October 30, 1945) was an American paleontologist, educator, and conservationist. The first vertebrate paleontologist on the West Coast of the United States, he is best known for his taxonomy of ver ...

, and Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

in 1918. He is also credited with helping develop the first deer hunting laws in New York state, legislation which spread to other states as well over time.

He was also a developer of

He was also a developer of wildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. It attempts to balance the needs of wildlife with the needs of people using the best availabl ...

; he believed its development to be harmonized with the concept of eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

. Grant helped to found the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and is the largest metropolitan zoo in ...

, build the Bronx River Parkway

The Bronx River Parkway (sometimes abbreviated as the Bronx Parkway) is a long parkway in downstate New York in the United States. It is named for the nearby Bronx River, which it parallels. The southern terminus of the parkway is at Story Aven ...

, save the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the ...

as an organizer of the American Bison Society

The American Bison Society (ABS) was founded in 1905 to help save the bison from extinction and raise public awareness about the species by pioneering conservationists and sportsmen including Ernest Harold Baynes (the Society's first secretary), ...

, and helped to create Glacier National Park and Denali National Park

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is an American national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali, the highest mountain in North America. The park and contiguous preserve ...

. In 1906, as Secretary of the New York Zoological Society

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

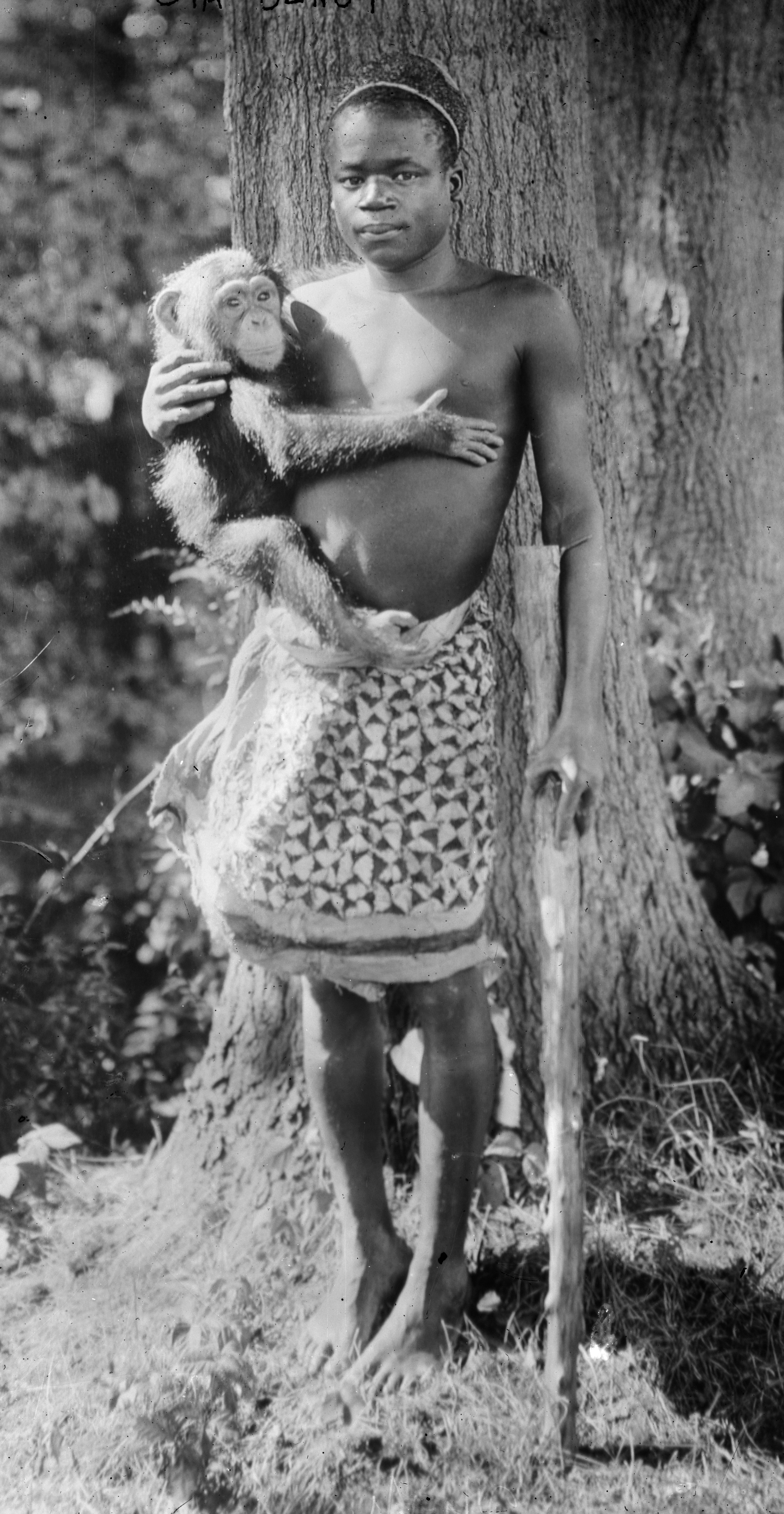

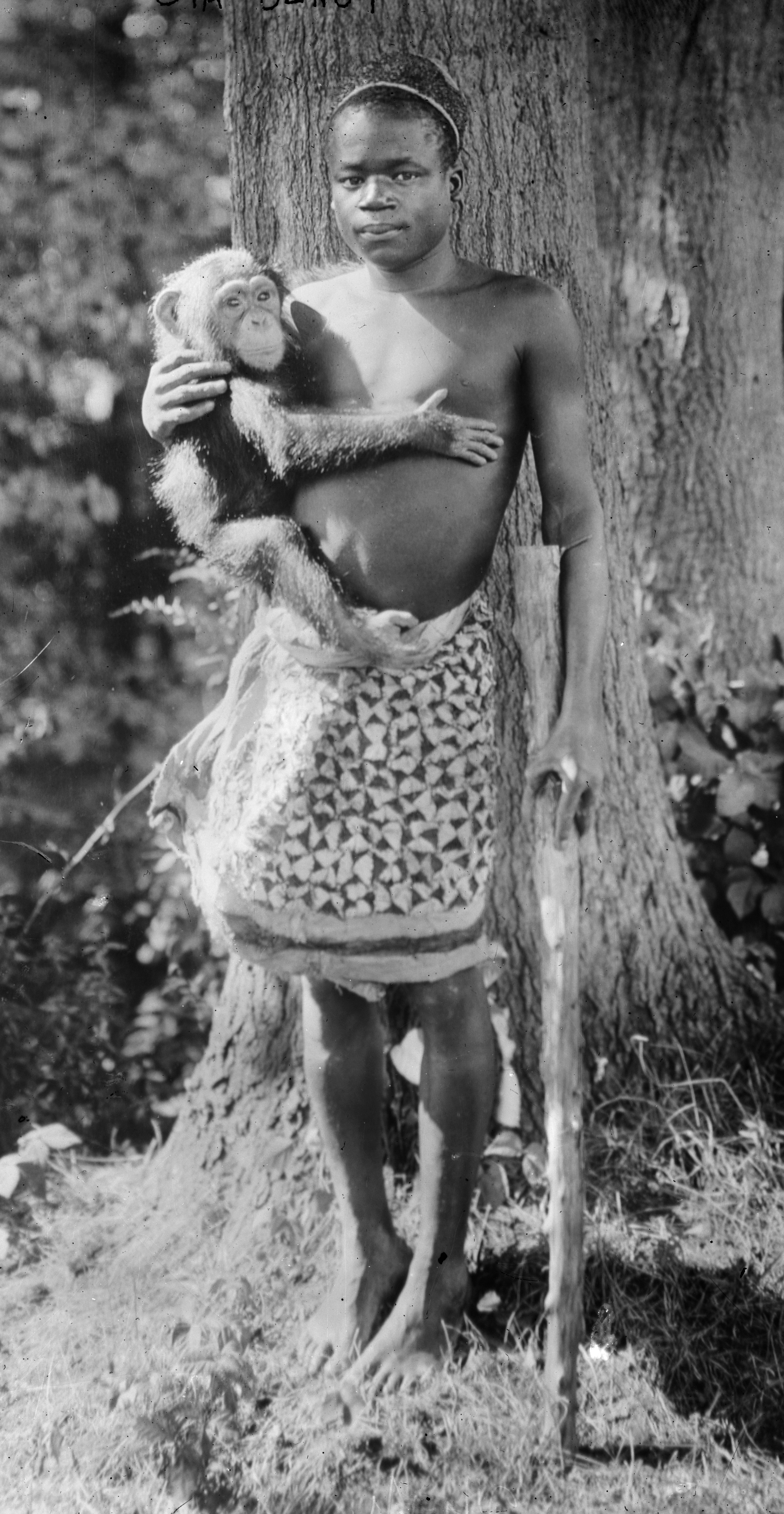

, he lobbied to put Ota Benga

Ota Benga ( – March 20, 1916) was a Mbuti ( Congo pygmy) man, known for being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been pur ...

, a Congolese man from the Mbuti people

The Mbuti people, or Bambuti, are one of several indigenous pygmy groups in the Congo region of Africa. Their languages are Central Sudanic languages and Bantu languages.

Subgroups

Bambuti are pygmy hunter-gatherers, and are one of the o ...

(a tribe of "pygmies"), on display alongside apes at the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and is the largest metropolitan zoo in ...

.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he served on the boards of many eugenic

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and philanthropic societies, including the board of trustees at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

, as director of the American Eugenics Society

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, vice president of the Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class found ...

, a founding member of the Galton Society, and one of the eight members of the International Committee of Eugenics. He was awarded the gold medal of the Society of Arts and Sciences in 1929. In 1931, the world's largest tree (in Dyerville, California) was dedicated to Grant, Merriam, and Osborn by the California State Board of Parks in recognition for their environmental efforts. A subspecies of caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

was named after Grant as well ('' Rangifer tarandus granti'', also known as Grant's Caribou). He was an early member of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United Sta ...

(a big game hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

organization) since 1893, and he mobilized its wealthy members to influence the government to conserve vast areas of land against encroaching industries. He was the head of the New York Zoological Society

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

from 1925 until his death.

Historian Jonathan Spiro has argued that Grant's interests in conservationism and eugenics were not unrelated: both are hallmarks of the early 20th-century Progressive movement, and both assume the need for various types of stewardship over their charges. In Grant's mind, natural resources needed to be conserved for the Nordic Race, to the exclusion of other races. Grant viewed the Nordic race lovingly as he did any of his endangered species, and considered the modern industrial society as infringing just as much on its existence as it did on the redwoods. Like many eugenicists, Grant saw modern civilization as a violation of "survival of the fittest", whether it manifested itself in the over-logging of the forests, or the survival of the poor via welfare or charity.

Nordicism

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, self-styled anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics, Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theo ...

'' (1916), an elaborate work of racial hygiene

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal ...

attempting to explain the racial history of Europe. The most significant of Grant's concerns was with the changing "stock" of American immigration of the early 20th century (characterized by increased numbers of immigrants from Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and Eastern Europe, as opposed to Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and Northern Europe), ''Passing of the Great Race'' was a "racial" interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, stating race as the basic motor of civilization.

Similar ideas were proposed by prehistorian Gustav Kossinna in Germany. Grant promoted the idea of the "Nordic race

The Nordic race was a racial concept which originated in 19th century anthropology. It was considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists divided the Caucasian race, claiming tha ...

", a loosely defined biological-cultural grouping rooted in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and S ...

, as the key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book was ''The racial basis of European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early ...

''. As an avid eugenicist, Grant further advocated the separation, quarantine, and eventual collapse of "undesirable" traits and "worthless race types" from the human gene pool and the promotion, spread, and eventual restoration of desirable traits and "worthwhile race types" conducive to Nordic society:

In the book, Grant recommends segregating In taxonomy, a segregate, or a segregate taxon is created when a taxon is split off from another taxon. This other taxon will be better known, usually bigger, and will continue to exist, even after the segregate taxon has been split off. A segregate ...

"unfavorable" races in ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

s, by installing civil organizations through the public health system to establish quasi-dictatorships in their particular fields. He states the expansion of non-Nordic race types in the Nordic system of freedom would actually mean a slavery to desires, passions, and base behaviors.

In turn, this corruption of society would lead to the subjection of the Nordic community to "inferior" races, who would in turn long to be dominated and instructed by "superior" ones utilizing authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic vot ...

powers. The result would be the submergence of the indigenous Nordic races under a corrupt and enfeebled system dominated by inferior races, and both in turn would be subjected by a new ruling race class.

Nordic theory, in Grant's formulation, was similar to many 19th-century racial philosophies, which divided the human species into primarily three distinct races: Caucasoids

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

(based in Europe - Whites), Negroids (based in Africa - Blacks), and Mongoloids (based in Asia - Asians). Nordic theory, however, further subdivided Caucasoids (Whites) into three groups: Nordics (who inhabited Northern Europe and other parts of the continent), Alpines

Alpines is a British duo based in Kingston upon Thames in South London, made up of Bob Matthews (guitar and production) and Catherine Pockson (pianist, singer and songwriter). Since forming in 2010, the band has toured and supported The Naked a ...

(whose territory included central Europe and parts of Asia), and Mediterraneans (who inhabited Southern Europe, North Africa, parts of Ireland and Wales, and the Middle East).

In Grant's view, Nordics probably evolved in a climate that "must have been such as to impose a rigid elimination of defectives through the agency of hard winters and the necessity of industry and foresight in providing the year's food, clothing, and shelter during the short summer. Such demands on energy, if long continued, would produce a strong, virile, and self-contained race which would inevitably overwhelm in battle nations whose weaker elements had not been purged by the conditions of an equally severe environment." The "Proto-Nordic" human, Grant reasoned, probably evolved in eastern Germany, Poland and Russia, before migrating northward to Scandinavia.

The Nordic, in his theory, was '' Homo europaeus'', the white man ''par excellence''. "It is everywhere characterized by certain unique specializations, namely, wavy brown or blond hair and blue, gray or light brown eyes, fair skin, high, narrow and straight nose, which are associated with great stature, and a long skull, as well as with abundant head and body hair." Grant categorized the Alpines as being the lowest of the three European races, with the Nordics as the pinnacle of civilization.

Grant, while aware of the "Nordic migration theory" into the Mediterranean, appears to reject this theory as an explanation for the high civilization features of the Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

.

Grant also considered North Africa as part of Mediterranean Europe:

Yet while Grant recognized Mediterraneans to have abilities in art, as quoted above, later in the text, he pondered if the Mediterranean achievements in civilization were due to Nordic original ideals and structure:

According to Grant, Nordics were in a dire state in the modern world, where, because of their abandonment of cultural values, rooted in religious or superstitious proto-racialism, they were close to committing "race suicide" by miscegenation and by being outbred by inferior stock taking advantage of the situation. Nordic theory was strongly embraced by the racial hygiene movement in Germany in the early 1920s and 1930s, in which, however, they typically used the term "Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

" instead of "Nordic", although the principal Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

ideologist, Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head o ...

, preferred "Aryo-Nordic" or "Nordic-Atlantean".

The book passed through multiple printings in the United States, and was translated into other languages, including German in 1925. By 1937, the book had sold 16,000 copies in the United States alone. In the introductions, Grant acknowledged his "great indebtedness" to three individuals: to Henry Fairfield Osborn, whose ''Men of the Old Stone Age Their Environment, Life and Art'' (1915) was a source of information for Grant's chapter on "Paleolithic Man," and to Mr. M. T. Pyne and Mr. Stewart Davison for their assistance and many helpful suggestions."

Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould (; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely read authors of popular science of his generation. Goul ...

described ''The Passing of the Great Race'' as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism". Grant's work was embraced by proponents of the National Socialist

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

movement in Germany and was the first non-German book ordered to be reprinted by the Nazis when they took power. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

wrote to Grant, "The book is my Bible."

Grant's work is considered one of the most influential and vociferous works of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

and eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

to come out of the United States. One of his long-time opponents was the anthropologist Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

. Grant disliked Boas and for several years tried to get him fired from his position at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. Boas and Grant were involved in a bitter struggle for control over the discipline of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

in the United States, while they both served (along with others) on the National Research Council Committee on Anthropology after the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

.

Grant represented the " hereditarian" branch of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

at the time, despite his relatively amateur status, and was staunchly opposed to and by Boas himself (and the latter's students), who advocated cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The portma ...

. Boas and his students eventually wrested control of the American Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropologists, ...

from Grant and his supporters, who had used it as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the ...

organization for his brand of anthropology. In response, Grant, along with American eugenicist and biologist Charles B. Davenport

Charles Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement.

Early life and education

Davenport was born in Stamford, Connecticut, to Amzi Benedict Davenport, a ...

, in 1918 founded the Galton Society as an alternative to Boas.

Immigration restriction

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class found ...

from 1922 to his death. Acting as an expert on world racial data, Grant also provided statistics for the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

to set the quotas on immigrants from certain European countries. Even after passing the statute, Grant continued to be irked that even a smattering of non-Nordics were allowed to immigrate to the country each year. He also assisted in the passing and prosecution of several anti-miscegenation

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different races. Anti-mi ...

laws, including the Racial Integrity Act of 1924

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasia ...

in the state of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

, where he sought to codify his particular version of the "one-drop rule

The one-drop rule is a legal principle of racial classification that was prominent in the 20th-century United States. It asserted that any person with even one ancestor of black ancestry ("one drop" of "black blood")Davis, F. James. Frontlin" ...

" into law.

Though Grant was extremely influential in legislating his view of racial theory, he began to fall out of favor in the United States in the early 1930s. The declining interest in his work has been attributed both to the effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, which resulted in a general backlash against Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism refers to various theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economics and politics, and which were largely defined by scholars in We ...

and related philosophies, and to the changing dynamics of racial issues in the United States during the interwar period. Rather than subdivide Europe into separate racial groups, the bi-racial (black vs. white) theory of Grant's protegé Lothrop Stoddard

Theodore Lothrop Stoddard (June 29, 1883 – May 1, 1950) was an American historian, journalist, political scientist, conspiracy theorist, white supremacist, and white nationalist. Stoddard wrote several books which advocated eugenics and sci ...

became more dominant in the aftermath of the Great Migration of African-Americans from Southern States to Northern and Western ones (Guterl 2001).

Legacy

According to historian of economics Thomas C. Leonard:Prominent American eugenicists, including movement leadersLeonard wrote that Grant also opposed war, had doubts about imperialism, and supportedCharles Davenport Charles Benedict Davenport (June 1, 1866 – February 18, 1944) was a biologist and eugenicist influential in the American eugenics movement. Early life and education Davenport was born in Stamford, Connecticut, to Amzi Benedict Davenport, ...and Madison Grant, were conservatives. They identified fitness with social and economic position, and they also were hard hereditarians, dubious of theLamarckian Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...inheritance clung to by progressives. But as eugenicists, these conservatives were not classical liberals. Like all eugenicists, they were illiberal. Conservatives do not object to state coercion so long as it is used for what they regard as the right purposes, and these men were happy to trample on individual rights to obtain the greater good of improved hereditary health....Historians invariably style Madison Grant a conservative, because he was a blueblood clubman from a patrician family, and his best- known work, ''The Passing of the Great Race,'' is a museum piece of scientific racism. But Grant’s eugenic ideas originated from a corner of the conservative impulse intimately connected to Progressivism: conservation.

birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

.

Grant became a part of popular culture in 1920s America, especially in New York. Grant's conservationism and fascination with zoological natural history made him influential among the New York elite, who agreed with his cause, most notably Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. Author F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and excess of the Jazz Age—a term he popularize ...

featured a reference to Grant in ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby ...

''. Tom Buchanan, a fatuous Long Island aristocrat married to Daisy, was reading a book called ''The Rise of the Colored Empires'' by "this man Goddard", blending Grant's ''Passing of the Great Race'' and his colleague Lothrop Stoddard

Theodore Lothrop Stoddard (June 29, 1883 – May 1, 1950) was an American historian, journalist, political scientist, conspiracy theorist, white supremacist, and white nationalist. Stoddard wrote several books which advocated eugenics and sci ...

's ''The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy

''The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World-Supremacy'' (1920), by Lothrop Stoddard, is a book about racialism and geopolitics, which describes the collapse of white supremacy and colonialism because of the population growth amo ...

''.

Grant left no offspring when he died in 1937 of nephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Types

* Glomerulonephritis is inflammation ...

. Several hundred people attended Grant's funeral, and he was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story " The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch ...

in Tarrytown, New York

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on the Metro-North ...

. He left a bequest of $25,000 to the New York Zoological Society

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator ...

to create "The Grant Endowment Fund for the Protection of Wild Life", $5,000 to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 int ...

, and another $5,000 to the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United Sta ...

. Relatives destroyed his personal papers and correspondence after his death.

At the postwar

At the postwar Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

, three pages of excerpts from Grant's ''Passing of the Great Race'' were introduced into evidence by the defense of Karl Brandt, Hitler's personal physician and head of the Nazi euthanasia program, in order to justify the population policies of the Third Reich, or at least indicate that they were not ideologically unique to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

.

Grant's works of "scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

" have been cited to demonstrate that many of the genocidal and eugenic ideas associated with the Third Reich did not arise specifically in Germany, and in fact that many of them had origins in other countries, including the United States. As such, because of Grant's well-connected and influential friends, he is often used to illustrate the strain of race-based eugenic thinking in the United States, which had some influence until the Second World War. Because of the use made of Grant's eugenics work by the policy-makers of Nazi Germany, his work as a conservationist has been somewhat ignored and obscured, as many organizations with which he was once associated (such as the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an environmental organization with chapters in all 50 United States, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded on May 28, 1892, in San Francisco, California, by Scottish-American preservationist John Muir, who b ...

) wanted to minimize their association with him. His racial theories, which were popularized in the 1920s, are today seen as discredited. The work of Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the movements known as historical ...

and his students, Ruth Benedict

Ruth Fulton Benedict (June 5, 1887 – September 17, 1948) was an American anthropologist and folklorist.

She was born in New York City, attended Vassar College, and graduated in 1909. After studying anthropology at the New School of Social Re ...

and Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural anthropologist who featured frequently as an author and speaker in the mass media during the 1960s and the 1970s.

She earned her bachelor's degree at Barnard C ...

, demonstrated that there were no inferior or superior races.

On June 15, 2021, California State Parks removed a memorial to Madison Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park placed in the park in 1948. The monument's removal is part of a broader effort in California Parks to address outdated exhibits and interpretations related to the founders of Save the Redwoods. In spring 2022, California State Parks will install a new interpretive panel, co-written with academic scholars, that tells a fuller story about Grant, his conservation legacy, and his central role in the eugenics movement.

Works

''The Caribou.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902. * "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903.

''The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904. *

The Rocky Mountain Goat.

' Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905.

''The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. *

New ed.

rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918 *

Rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921. *

Fourth rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936. *

Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California

'' New York: Zoological Society, 1919.Reprinted i

''The National Geographic''

Vol. XXXVII, January/June, 1920.

''Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana.''

Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919.

''The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America''

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

Selected articles

"The Depletion of American Forests"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894. * "The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks", ''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVII, 1894.

"A Canadian Moose Hunt"

In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), ''Hunting in Many Lands.'' New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895.

"The Future of Our Fauna"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', No. 34, June 1909.

"History of the Zoological Society"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910.

"Condition of Wild Life in Alaska"

In: ''Hunting at High Altitudes.'' New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913.

"Wild Life Protection"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916.

"The Passing of the Great Race"

''Geographical Review'', Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916.

"The Physical Basis of Race"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. III, January 1917.

"Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity"

''The Journal of Heredity'', Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919.

"Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. VII, August 1921. * "Racial Transformation of America", ''The North American Review'', March 1924. * "America for the Americans", ''The Forum'', September 1925.

See also

*Racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagoni ...

* Institutional racism

Institutional racism, also known as systemic racism, is a form of racism that is embedded in the laws and regulations of a society or an organization. It manifests as discrimination in areas such as criminal justice, employment, housing, health ...

* Eugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the Genetics, genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th c ...

* Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

References

Further reading

* "Madison Grant, 71, Zoologist, Is Dead", ''The New York Times'' (May 31, 1937), p. 15. * Allen, Garland E. (2013). "'Culling the Herd': Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940," ''Journal of the History of Biology'' 46, pp. 31–72. *Barkan, Elazar (1992). ''The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. * Cooke, Kathy J. (2000)"Grant, Madison"

''American National Biography''. Oxford University Press. Online. * Degler, Carl N. (1991). ''In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought''. Oxford University Press. * Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 38 (3), pp. 523–540. * Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). ''The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.1 (2020): 3-18. * Leonard, Thomas C. ''Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era'' (Princeton UP, 2016) * Leonard, Thomas C. " 'More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era." ''History of Political Economy// 35.4 (2003): 687-712

online

* Marcus, Alan P. "The Dangers of the Geographical Imagination in the US Eugenics Movement." ''Geographical Review'' 111.1 (2021): 36-56. * Purdy, Jedediah (2015)

"Environmentalism's Racist History"

''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

''.

*

* Spiro, Jonathan P. ''Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant'' (Univ. of Vermont Press, 2009excerpt

* Spiro, Jonathan P. "Nordic vs. Anti-Nordic: The Galton Society and the American Anthropological Association", ''Patterns of Prejudice'' 36#1 (2002): 35–48. * Regal, Brian (2002). ''Henry Fairfield Osborn: Race and the Search for the Origins of Man''. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. * Regal, Brian (2004). "Maxwell Perkins and Madison Grant: Eugenics Publishing at Scribners", ''Princeton University Library Chronicle'' 65#2, pp. 317–341.

External links

*Excerpts from ''Passing of the Great Race'' used at the Nuremberg Trials

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Grant, Madison 1865 births 1937 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American writers 20th-century American anthropologists Amateur anthropologists American eugenicists American conservationists American conspiracy theorists American hunters American nationalists American people of English descent American people of French descent American political writers American white supremacists American zoologists Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Columbia Law School alumni Deaths from nephritis Lawyers from New York City Nordicism Philanthropists from New York (state) Race and intelligence controversy Proponents of scientific racism Writers from New York City Yale University alumni