Lytta vesicatoria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Spanish fly (''Lytta vesicatoria'') is an aposematic emerald-green

The adult Spanish fly is a slender, soft-bodied metallic and

The adult Spanish fly is a slender, soft-bodied metallic and

Cantharidin, the principal active component in preparations of Spanish fly, was first isolated and named in 1810 by the French chemist

Cantharidin, the principal active component in preparations of Spanish fly, was first isolated and named in 1810 by the French chemist

beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

in the blister beetle

Blister beetles are beetles of the family Meloidae, so called for their defensive secretion of a blistering agent, cantharidin. About 7,500 species are known worldwide. Many are conspicuous and some are aposematically colored, announcing their ...

family (Meloidae). It is distributed across Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

.

The species and others in its family were used in traditional apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is a mostly archaic term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses '' materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons, and patients. The modern chemist (British English) or pharmacist (British and North Amer ...

preparations as "Cantharides". The insect is the source of the terpenoid cantharidin, a toxic blistering agent once used as an exfoliating agent, anti-rheumatic drug and an aphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases sexual desire, sexual attraction, sexual pleasure, or sexual behavior. Substances range from a variety of plants, spices, foods, and synthetic chemicals. Natural aphrodisiacs like cannabis or cocai ...

. The substance has also found culinary use in some blends of the North African spice mix '' ras el hanout''. Its various supposed benefits have been responsible for accidental poisonings.

Etymology and taxonomy

The generic name is from the Greek λύττα (''lytta''), meaning martial rage, raging madness, Bacchic frenzy, orrabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, ...

. The specific name is derived from Latin ''vesica'', blister.

''Lytta vesicatoria'' was formerly named ''Cantharis vesicatoria'', although the genus '' Cantharis'' is in an unrelated family, Cantharidae

The soldier beetles (Cantharidae) are relatively soft-bodied, straight-sided beetles. They are cosmopolitan in distribution. One of the first described species has a color pattern reminiscent of the red coats of early British soldiers, hence the ...

, the soldier beetles. It was classified there erroneously until the Danish zoologist Johan Christian Fabricius

Johan Christian Fabricius (7 January 1745 – 3 March 1808) was a Danish zoologist, specialising in "Insecta", which at that time included all arthropods: insects, arachnids, crustaceans and others. He was a student of Carl Linnaeus, and is co ...

corrected its name in his ''Systema entomologiae'' in 1775. He reclassified the Spanish fly as the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specim ...

of the new genus ''Lytta

'' Lytta vesicatoria'', the Spanish fly

''Lytta'' is a genus of blister beetles in the family Meloidae. There are about 70 described species in North America, and over 100 species worldwide.

Selected species

These species, and others, belong ...

'', in the family Meloidae.

Description and ecology

The adult Spanish fly is a slender, soft-bodied metallic and

The adult Spanish fly is a slender, soft-bodied metallic and iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

golden-green insect, one of the blister beetle

Blister beetles are beetles of the family Meloidae, so called for their defensive secretion of a blistering agent, cantharidin. About 7,500 species are known worldwide. Many are conspicuous and some are aposematically colored, announcing their ...

s. It is approximately wide by long.

The female lays her fertilised eggs on the ground, near the nest of a ground-nesting solitary bee. The larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

...

e are very active as soon as they hatch. They climb a flowering plant and await the arrival of a solitary bee

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyletic lineage within the superfami ...

. They hook themselves on to the bee using the three claws on their legs that give the first instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'', "form", "likeness") is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, between each moult (''ecdysis''), until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to grow or ...

larvae their name, triungulins (from Latin ''tri'', three, and ''ungulus'', claw). The bee carries the larvae back to its nest, where they feed on bee larvae and the bees' food supplies. The larvae are thus somewhere between predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill t ...

s and parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson h ...

s. The active larvae moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

into very different, more typically scarabaeoid larvae for the remaining two or more instars, in a development type called hypermetamorphosis. The adults emerge from the bees' nest and fly to the woody plants on which they feed.

The defensive chemical cantharidin, for which the beetle is known, is synthesised only by males; females obtain it from males during mating, as the spermatophore

A spermatophore or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especially salamanders and arthropods, and transferred in entirety to the female's ovipore during reproduction. Spermatophore ...

contains some. This may be a nuptial gift

A nuptial gift is a nutritional gift given by one partner in some animals' sexual reproduction practices.

Formally, a nuptial gift is a material presentation to a recipient by a donor during or in relation to sexual intercourse that is not simpl ...

, increasing the value of mating to the female, and thus increasing the male's reproductive fitness. Zoologists note that the conspicuous coloration, the presence of a powerful toxin, and the adults' aggregating behaviour in full view of any predators strongly suggest aposematism

Aposematism is the advertising by an animal to potential predators that it is not worth attacking or eating. This unprofitability may consist of any defences which make the prey difficult to kill and eat, such as toxicity, venom, foul taste ...

among the blistering meloid beetles.

Range and habitat

The Spanish fly is found across Eurasia, though it is a mainly a southern European species, with some records from southernGreat Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and Poland.

Adult beetles primarily feed on leaves of ash

Ash or ashes are the solid remnants of fires. Specifically, ''ash'' refers to all non-aqueous, non-gaseous residues that remain after something burns. In analytical chemistry, to analyse the mineral and metal content of chemical samples, ash ...

, lilac

''Syringa'' is a genus of 12 currently recognized species of flowering woody plants in the olive family or Oleaceae called lilacs. These lilacs are native to woodland and scrub from southeastern Europe to eastern Asia, and widely and commonl ...

, amur privet, honeysuckle

Honeysuckles are arching shrubs or twining vines in the genus ''Lonicera'' () of the family Caprifoliaceae, native to northern latitudes in North America and Eurasia. Approximately 180 species of honeysuckle have been identified in both con ...

and white willow

''Salix alba'', the white willow, is a species of willow native to Europe and western and central Asia.Meikle, R. D. (1984). ''Willows and Poplars of Great Britain and Ireland''. BSBI Handbook No. 4. .Rushforth, K. (1999). ''Trees of Britain ...

. It is occasionally found on plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found ...

, rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

, and elm.

Interaction with humans

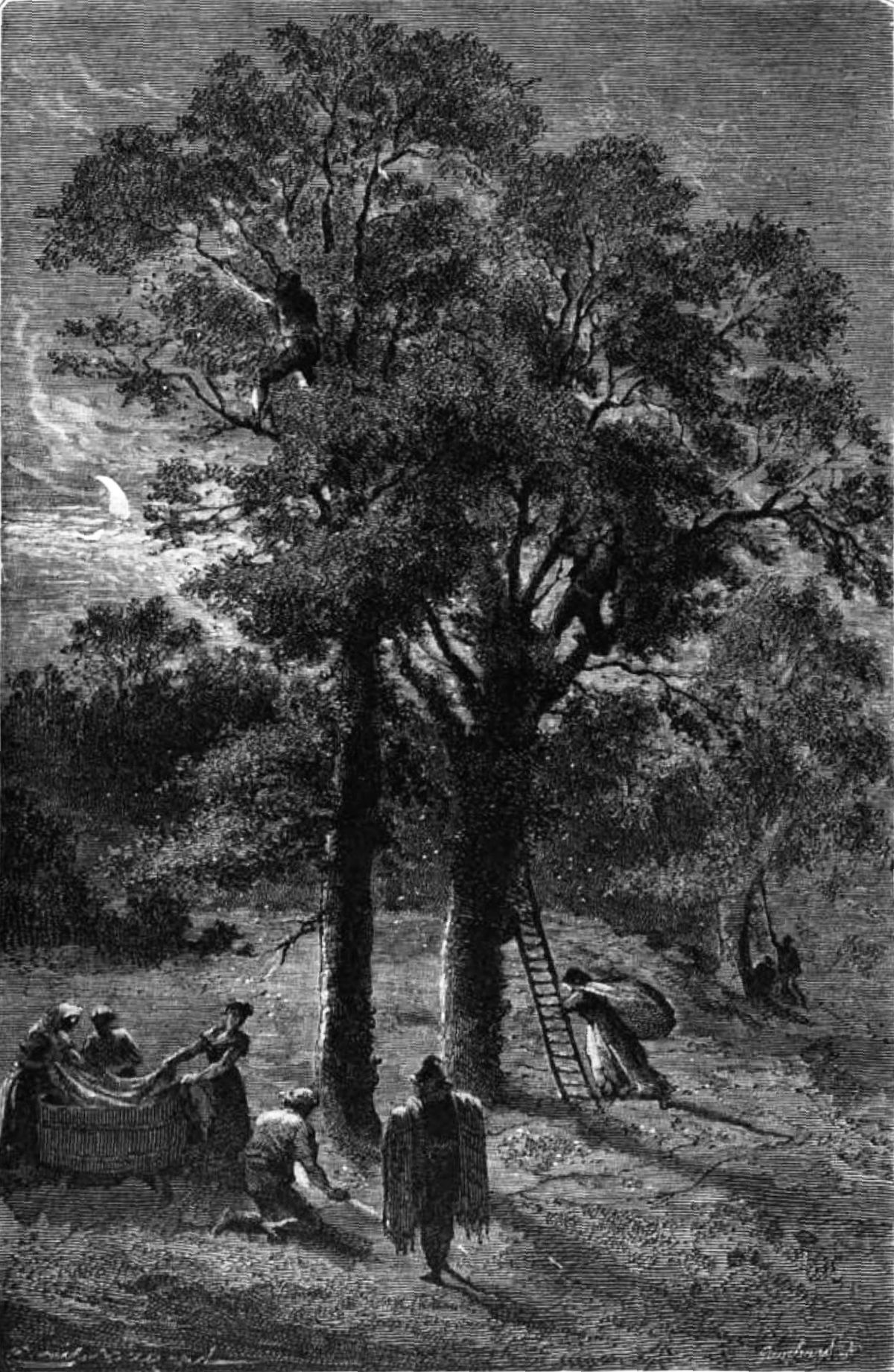

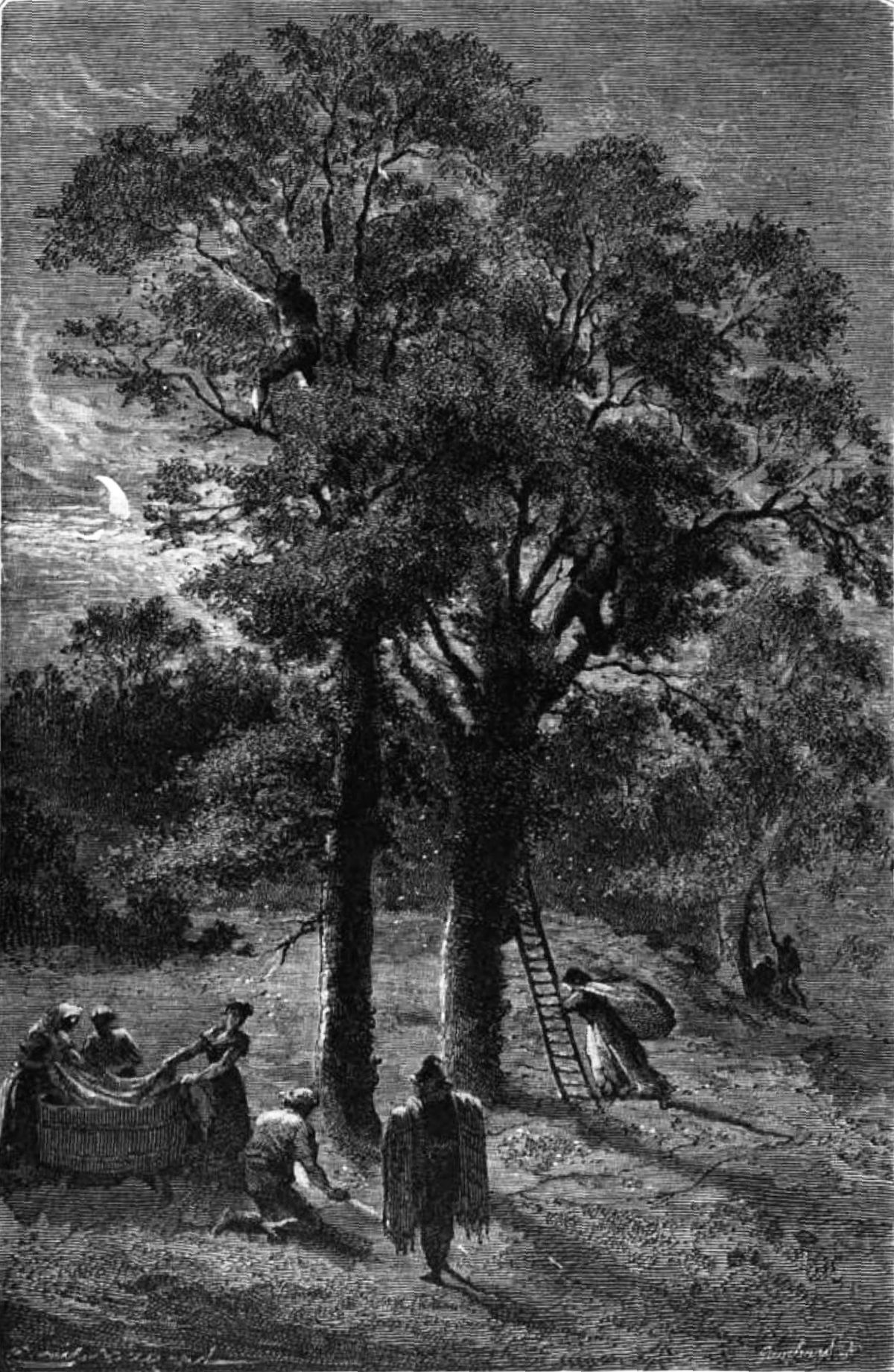

Preparation of cantharidin

Pierre Robiquet

Pierre Jean Robiquet (13 January 1780 – 29 April 1840) was a French chemist. He laid founding work in identifying amino acids, the fundamental building blocks of proteins. He did this through recognizing the first of them, asparagine, in 180 ...

, who demonstrated that it was the principal agent responsible for the aggressively blistering properties of this insect's egg coating. It was asserted at that time that it was as toxic as the most violent poisons then known, such as strychnine

Strychnine (, , US chiefly ) is a highly toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the e ...

.

Each beetle contains some 0.2–0.7 mg of cantharidin, males having significantly more than females. The beetle secretes the agent orally, and exudes it from its joints as a milky fluid. The potency of the insect as a blistering agent has been known since antiquity and the activity has been used in various ways. This has led to its small-scale commercial preparation and sale, in a powdered form known as ''cantharides'' (from the plural of Greek κανθαρίς, ''Kantharis'', beetle), obtained from dried and ground beetles. The crushed powder is of yellow-brown to brown-olive color with iridescent

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to gradually change color as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, feathers, butterfl ...

reflections, is of disagreeable scent, and is bitter to taste. Cantharidin, the active agent, is a terpenoid, and is produced by some other insects, such as '' Epicauta immaculata''.

Toxicity and poisonings

Cantharidin is dangerously toxic, inhibiting the enzyme phosphatase 2A. It causes irritation, blistering, bleeding and discomfort. These effects can escalate to erosion andbleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

of mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

in each system, sometimes followed by severe gastro-intestinal bleeding and acute tubular necrosis and glomerular destruction, resulting in gastro-intestinal and renal dysfunction, organ failure, and death.

Preparations of Spanish fly and its active agent have been implicated in both inadvertent Note: ''the active agent appears variously as cantharidin, and "cantharadin" or "canthariadin"'' (sic). and intentional poisonings. Arthur Kendrick Ford was imprisoned in 1954 for the unintended deaths of two women surreptitiously given candies laced with cantharidin, which he had intended to act as an aphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases sexual desire, sexual attraction, sexual pleasure, or sexual behavior. Substances range from a variety of plants, spices, foods, and synthetic chemicals. Natural aphrodisiacs like cannabis or cocai ...

. It has been suggested that George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

was treated with Spanish fly for epiglottitis

Epiglottitis is the inflammation of the epiglottis—the flap at the base of the tongue that prevents food entering the trachea (windpipe). Symptoms are usually rapid in onset and include trouble swallowing which can result in drooling, changes ...

, the condition which caused his death.

Currently the cantharidin in US, in the form of collodion, is used in the treatment of warts and molluscum.

Culinary uses

InMorocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

and other parts of North Africa, spice blends known as '' ras el hanout'' sometimes included as a minor ingredient "green metallic beetles", inferred to be ''L. vesicatoria'', although its sale in Moroccan spice markets was banned in the 1990s. ''Dawamesk'', a spread or jam made in North Africa and containing hashish

Hashish ( ar, حشيش, ()), also known as hash, "dry herb, hay" is a drug made by compressing and processing parts of the cannabis plant, typically focusing on flowering buds (female flowers) containing the most trichomes. European Monitoring ...

, almond paste

Almond paste is made from ground almonds or almond meal and sugar in equal quantities, with small amounts of cooking oil, beaten eggs, heavy cream or corn syrup added as a binder. It is similar to ''marzipan'', but has a coarser texture. Almond pas ...

, pistachio nuts, sugar, orange or tamarind

Tamarind (''Tamarindus indica'') is a leguminous tree bearing edible fruit that is probably indigenous to tropical Africa. The genus ''Tamarindus'' is monotypic, meaning that it contains only this species. It belongs to the family Fabacea ...

peel, clove

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, ''Syzygium aromaticum'' (). They are native to the Maluku Islands (or Moluccas) in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice, flavoring or fragrance in consumer products, ...

s, and other various spices, occasionally included cantharides.

Other uses

Inancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapt ...

, the beetles were mixed with human excrement, arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As and atomic number 33. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. Arsenic is a metalloid. It has various allotropes, b ...

, and wolfsbane to make the world's first recorded stink bomb

A stink bomb, sometimes called a stinkpot, is a device designed to create an unpleasant smell. They range in effectiveness from being used as simple pranks to military grade malodorants or riot control chemical agents.

History

A stink bomb ...

.

In ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Spanish fly was used to attempt to treat skin diseases, while in medieval Persia, Islamic medicine applied Spanish fly, named ''ḏarārīḥ'' (الذراح), to attempt to prevent rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, ...

.

In 19th century, Spanish fly was used externally mainly as blistering agent and local irritant; also, in chronic gonorrhoea, paralysis, lepra, ulcers therapy. ''L. vesicatoria'' was used internally as a diuretic stimulant and aphrodisiac.

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spanish fly Meloidae Abortifacients Beetles described in 1758 Poisonous animals Insect products Beetles of Europe Insects in culture