Lutheran Orthodoxy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lutheran orthodoxy was an era in the history of

In contrast,

In contrast,

The Inspiration of Scripture: A Study of the Theology of the 17th Century Lutheran Dogmaticians

'' London: Oliver and Boyd, 1957. Scholastic Lutheran theologians engaged in a twofold task. First, they collected texts, arranged them, supported them with arguments, and gave rebuttals based on the theologians before them. Second, they completed their process by going back to the pre-Reformation scholastics in order to gather additional material which they assumed the Reformation also accepted. Even though the Lutheran scholastic theologians added their own criticism to the pre-Reformation scholastics, they still had an important influence. Mainly, this practice served to separate their theology from direct interaction with Scripture. However, their theology was still built on Scripture as an authority that needed no external validation. Their scholastic method was intended to serve the purpose of their theology. Some dogmaticians preferred to use the synthetic method, while others used the analytic method, but all of them allowed Scripture to determine the form and content of their statements.

Scholasticism in the Luth. Church

” ''Lutheran Cyclopedia.'' New York: Scribner, 1899. pp. 434–5.

Sketch of the dogmaticians of Lutheran orthodoxy

from ''The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church'' by Heinrich Schmid

Lutheran Legacy

{{Authority control

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

, which began in 1580 from the writing of the ''Book of Concord

''The Book of Concord'' (1580) or ''Concordia'' (often referred to as the ''Lutheran Confessions'') is the historic doctrinal standard of the Lutheran Church, consisting of ten credal documents recognized as authoritative in Lutheranism since ...

'' and ended at the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. Lutheran orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

was paralleled by similar eras in Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

and tridentine Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

after the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

.

Lutheran scholasticism was a theological method that gradually developed during the era of Lutheran orthodoxy. Theologians used the neo-Aristotelian form of presentation, already popular in academia, in their writings and lectures. They defined the Lutheran faith and defended it against the polemic

Polemic () is contentious rhetoric intended to support a specific position by forthright claims and to undermine the opposing position. The practice of such argumentation is called ''polemics'', which are seen in arguments on controversial topic ...

s of opposing parties.

History

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

died in 1546, and Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

in 1560. After the death of Luther came the period of the Schmalkaldic War

The Schmalkaldic War (german: link=no, Schmalkaldischer Krieg) was the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire (simultaneously King Charles I ...

and disputes among Crypto-Calvinists

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luth ...

, Philippists

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Before Luther's death

''Philippists'' was the designation usually applied in the latter half of the sixteenth century to the followers of Phili ...

, Sacramentarians

The Sacramentarians were Christians during the Protestant Reformation who denied not only the Roman Catholic transubstantiation but also the Lutheran sacramental union (as well as similar doctrines such as consubstantiation).

During the turbule ...

, Ubiquitarians The Ubiquitarians, also called Ubiquists, were a Protestant sect that held that the body of Christ was everywhere, including the Eucharist. The sect was started at the Lutheran synod of Stuttgart, 19 December 1559, by Johannes Brenz (1499–15 ...

, and Gnesio-Lutherans

Gnesio-Lutherans (from Greek γνήσιος nesios genuine, authentic) is a modern name for a theological party in the Lutheran churches, in opposition to the Philippists after the death of Martin Luther and before the Formula of Concord. In t ...

.

Early orthodoxy: 1580–1600

The ''Book of Concord

''The Book of Concord'' (1580) or ''Concordia'' (often referred to as the ''Lutheran Confessions'') is the historic doctrinal standard of the Lutheran Church, consisting of ten credal documents recognized as authoritative in Lutheranism since ...

'' gave inner unity to Lutheranism, which had many controversies, mostly between Gnesio-Lutherans

Gnesio-Lutherans (from Greek γνήσιος nesios genuine, authentic) is a modern name for a theological party in the Lutheran churches, in opposition to the Philippists after the death of Martin Luther and before the Formula of Concord. In t ...

and Philippists

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Before Luther's death

''Philippists'' was the designation usually applied in the latter half of the sixteenth century to the followers of Phili ...

, in Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

outward pressure and in alleged "crypto-Calvinist

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luth ...

ic" influence. Lutheran theology became more stable in its theoretical definitions.

High orthodoxy: 1600–1685

Lutheran scholasticism

Lutheran orthodoxy was an era in the history of Lutheranism, which began in 1580 from the writing of the ''Book of Concord'' and ended at the Age of Enlightenment. Lutheran orthodoxy was paralleled by similar eras in Calvinism and tridentine ...

developed gradually, especially for the purpose of disputation with the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, and it was finally established by Johann Gerhard (1582-1637). Abraham Calovius (1612-1686) represents the climax of the scholastic paradigm

In science and philosophy, a paradigm () is a distinct set of concepts or thought patterns, including theories, research methods, postulates, and standards for what constitute legitimate contributions to a field.

Etymology

''Paradigm'' comes f ...

in orthodox Lutheranism. Other orthodox Lutheran theologians include (for example) Martin Chemnitz, Aegidius Hunnius

Aegidius Hunnius the Elder (21 December 1550 in Winnenden – 4 April 1603 in Wittenberg) was a Lutheran theologian of the Lutheran scholastic tradition and father of Nicolaus Hunnius.

Life

Hunnius went rapidly through the preparatory scho ...

, Leonhard Hutter

Leonhard Hutter (also ''Hütter'', Latinized as Hutterus; 19 January 1563 – 23 October 1616) was a German Lutheran theologian.

Life

He was born at Nellingen near Ulm. From 1581 he studied at the universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig, Heidelberg ...

(1563-1616), Nicolaus Hunnius, Jesper Rasmussen Brochmand, Salomo Glassius

Salomo Glassius (german: Salomon Glaß; 20 May 1593 – 27 July 1656) was a German theologian and biblical critic born at Sondershausen, in the principality of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen.

In 1612 he entered the University of Jena. In 1615, with ...

, Johann Hülsemann, Johann Conrad Dannhauer

Johann Conrad Dannhauer (b. at Köndringen (10 m. n. of Freiburg) 24 March 1603; d. at Strasburg 7 November 1666) was an Orthodox Lutheran theologian and teacher of Spener.

Dannhauer began his education in the gymnasium at Strasburg and was ...

, Valerius Herberger

Valerius Herberger (21 April 1562 – 18 May 1627) was a German Lutheran preacher and theologian.

Life

He was born at Fraustadt, Silesia (now Wschowa in Poland). He studied for three years at Freystadt in Silesia (now Kożuchów in Poland), and ...

, Johannes Andreas Quenstedt

Johannes Andreas Quenstedt (13 August 1617 – 22 May 1688) was a German Lutheran dogmatician in the Lutheran scholastic tradition.

Quenstedt was born at Quedlinburg, a nephew of Johann Gerhard. He was educated at the University of Helmstedt, 16 ...

, Johann Friedrich König and Johann Wilhelm Baier

Johann Wilhelm Baier (11 November 1647 – 19 October 1695) was a German theologian in the Lutheran scholastic tradition. He was born at Nuremberg, and died at Weimar.

He studied philology, especially Oriental, and philosophy at Altdorf from 16 ...

.

The theological heritage of Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

arose again in the Helmstedt

Helmstedt (; Eastphalian: ''Helmstidde'') is a town on the eastern edge of the German state of Lower Saxony. It is the capital of the District of Helmstedt. The historic university and Hanseatic city conserves an important monumental heritage o ...

School and especially in the theology of Georgius Calixtus

Georg Calixtus, Kallisøn/Kallisön, or Callisen (14 December 1586 – 19 March 1656) was a German Lutheran theologian who looked to reconcile all Christendom by removing all differences that he deemed "unimportant".

Biography

Calixtus was born ...

(1586-1656), which caused the syncretistic controversy

The syncretistic controversy was the theological debate provoked by the efforts of Georg Calixt and his supporters to secure a basis on which the Lutherans could make overtures to the Roman Catholic and the Reformed Churches. It lasted from 1640 ...

of 1640–1686. Another theological issue was the Crypto-Kenotic Controversy of 1619–1627.

Late orthodoxy: 1685–1730

Late orthodoxy was torn by influences fromrationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

and pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

. Orthodoxy produced numerous postil

A postil or postill ( la, postilla; german: Postille) was originally a term for Bible commentaries. It is derived from the Latin ''post illa verba textus'' ("after these words from Scripture"), referring to biblical readings. The word first occurs ...

s, which were important devotional readings. Along with hymns, they conserved orthodox Lutheran spirituality during this period of heavy influence from pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

and neology

Neology ("study of new hings) was the name given to the rationalist theology of Germany or the rationalisation of the Christian religion. It was preceded by slightly less radical Wolffism.

''Chambers English Dictionary'' of 1872 adds the appl ...

. Johann Gerhard, Heinrich Müller Heinrich Müller may refer to:

* Heinrich Müller (cyclist) (born 1926), Swiss cyclist

* Heinrich Müller (footballer, born 1888) (1888–1957), Swiss football player and manager

* Heinrich Müller (footballer, born 1909) (1909–2000), Austrian ...

and Christian Scriver

Christian Scriver (2 January 1629 – 5 April 1693) was a German Lutheran minister and devotional writer.

Biography

Christian Scriver was born at Rendsburg in the Duchy of Schleswig, Germany. He entered the University of Rostock in 1647. ...

wrote other kinds of devotional literature.

The last prominent orthodox Lutheran theologian before the Enlightenment and Neology

Neology ("study of new hings) was the name given to the rationalist theology of Germany or the rationalisation of the Christian religion. It was preceded by slightly less radical Wolffism.

''Chambers English Dictionary'' of 1872 adds the appl ...

was David Hollatz. A later orthodox theologian, Valentin Ernst Löscher, took part in a controversy against Pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

. Mediaeval mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

tradition continued in the works of Martin Moller, Johann Arndt

Johann Arndt (or Arnd; 27 December 155511 May 1621) was a German Lutheran theologian who wrote several influential books of devotional Christianity. Although reflective of the period of Lutheran Orthodoxy, he is seen as a forerunner of Pietism, a ...

and Joachim Lütkemann. Pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

became a rival of orthodoxy but adopted some orthodox devotional literature, such as those of Arndt, Scriver and Stephan Prätorius, which have often been later mixed with pietistic literature.

David Hollatz combined mystic and scholastic elements.

Content

Scholastic dogmaticians followed the historical order of God's saving acts. First Creation was taught, then the Fall, followed by Redemption, and finished by the Last Things.Hägglund, Bengt, ''History of Theology''. trans. Lund, Gene, L. St. Louis: Concordia, 1968. p. 302. This order, as an independent part of the Lutheran tradition, was not derived from any philosophical method. It was followed not only by those using the loci method, but also those using the analytical. The usual order of the loci: #Holy Scriptures #Trinity (includingChristology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Diff ...

and the doctrine of the Holy Spirit)

#Creation

#Providence

#Predestination

#Image of God

#Fall of Man

#Sin

#Free Will

#Law

#Gospel

#Repentance

#Faith and Justification

#Good Works

#Sacraments

#Church

#Three Estates

#Last Things

Lutheran scholasticism

Background

High Scholasticism inWestern Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two sub-divisions of Christianity ( Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the Old Catholi ...

aimed at an exhaustive treatment of theology, supplementing revelation by the deductions of reason. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

furnished the rules according to which it proceeded, and after a while he became the authority for both the source and process of theology.

Initial rejection

Lutheranism began as a vigorous protest against scholasticism, starting withMartin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

. Around the time he became a monk, Luther sought assurances about life, and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

and the scholastics William of Ockham

William of Ockham, OFM (; also Occam, from la, Gulielmus Occamus; 1287 – 10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and Catholic theologian, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small vil ...

and Gabriel Biel

Gabriel Biel (; 1420 to 1425 – 7 December 1495) was a German scholastic philosopher and member of the Canons Regular of the Congregation of Windesheim, who were the clerical counterpart to the Brethren of the Common Life.

Biel was born in Sp ...

. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 5. He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi Bartholomaeus Arnoldi, Augustinians, OSA (usually called Usingen; german: Bartholomäus Arnoldi von Usingen; 1465 – 9 September 1532) was an Augustinians, Augustinian friar and doctor of divinity who taught Martin Luther and later turned into his ...

von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers, and to test everything himself by experience. Marty, Martin. ''Martin Luther''. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 6. Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

, but none about the importance, for Luther, of loving God. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter's emphasis on reason. For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

, he believed, and Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

therefore became increasingly important to him.

In particular, Luther wrote theses 43 and 44 for his student Franz Günther to publicly defend in 1517 as part of earning his Baccalaureus Biblicus degree:It is not merely incorrect to say that without Aristotle no man can become a theologian; on the contrary, we must say: he is no theologian who does not become one without AristotleMartin Luther held that it was "not at all in conformity with the New Testament to write books about Christian doctrine." He noted that before the Apostles wrote books, they "previously preached to and converted the people with the physical voice, which was also their real apostolic and New Testament work." To Luther, it was necessary to write books to counter all the false teachers and errors of the present day, but writing books on Christian teaching came at a price. "But since it became necessary to write books, there is already a great loss, and there is uncertainty as to what is meant." Martin Luther taught preaching and lectured upon the

books of the Bible

A biblical canon is a set of texts (also called "books") which a particular Jewish or Christian religious community regards as part of the Bible.

The English word ''canon'' comes from the Greek , meaning " rule" or " measuring stick". The u ...

in an exegetical manner. To Luther, St. Paul was the greatest of all systematic theologians

Systematic may refer to:

Science

* Short for systematic error

* Systematic fault

* Systematic bias, errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by an inaccuracy (involving either the observation or measurement process) inherent ...

, and his Epistle to the Romans

The Epistle to the Romans is the sixth book in the New Testament, and the longest of the thirteen Pauline epistles. Biblical scholars agree that it was composed by Paul the Apostle to explain that salvation is offered through the gospel of Jes ...

was the greatest dogmatics textbook of all time.

Analysis of Luther's works, however, reveals a reliance on scholastic distinctions and modes of argument even after he had dismissed scholasticism entirely. Luther seems to be comfortable with the use of such theological methods so long as the content of theology is normed by scripture, though his direct statements regarding scholastic method are unequivocally negative.

Loci method

Beginning of the loci method

In contrast,

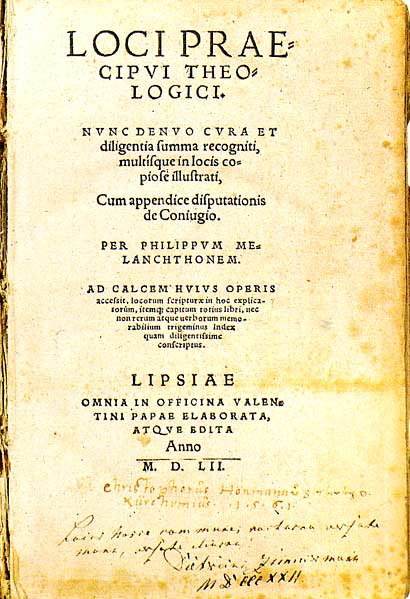

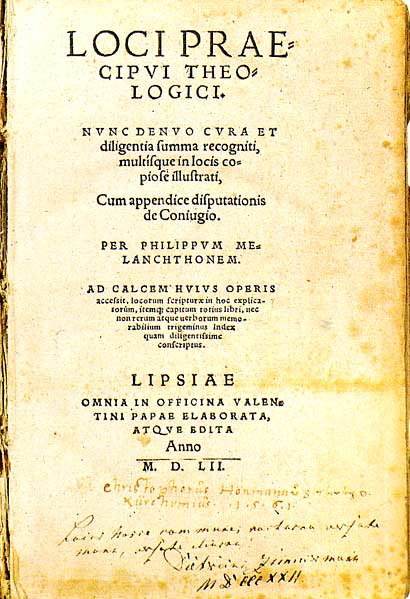

In contrast, Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

scarcely began to lecture on Romans before he decided to formulate and arrange the definitions of the common theological terms of the epistle in his '' Loci Communes''.

Flourishing of the loci method

Martin Chemnitz,Mathias Haffenreffer

Matthias Hafenreffer (24 June 1561 22 October 1619) was a German orthodox Lutheran theologian in the Lutheran scholastic tradition.

Born at Lorch (Württemberg), Hafenreffer was professor at Tübingen from 1592 until his death in 1617. He was ...

, and Leonhard Hutter

Leonhard Hutter (also ''Hütter'', Latinized as Hutterus; 19 January 1563 – 23 October 1616) was a German Lutheran theologian.

Life

He was born at Nellingen near Ulm. From 1581 he studied at the universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig, Heidelberg ...

simply expanded upon Melanchthon's ''Loci Communes''. With Chemnitz, however, a biblical method prevailed. At Melanchthon's suggestion he undertook a course of self-study. He began by carefully working through the Bible in the original languages while also answering questions that had previously puzzled him. When he felt ready to move on, he turned his attention to reading through the early theologians of the church slowly and carefully. Then he turned to current theological concerns and once again read painstakingly while making copious notes. His tendency was to constantly support his arguments with what is now known as biblical theology

Because scholars have tended to use the term in different ways, Biblical theology has been notoriously difficult to define.

Description

Although most speak of biblical theology as a particular method or emphasis within biblical studies, some scho ...

. He understood biblical revelation to be progressive—building from the earlier books to the later ones—and examined his supporting texts in their literary contexts and historical settings.

Analytic method

Properly speaking, Lutheran scholasticism began in the 17th century, when the theological faculty ofWittenberg

Wittenberg ( , ; Low Saxon: ''Wittenbarg''; meaning ''White Mountain''; officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg (''Luther City Wittenberg'')), is the fourth largest town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Wittenberg is situated on the River Elbe, north of ...

took up the scholastic method to fend off attacks by Jesuit theologians of the Second Scholastic Period of Roman Catholicism.

Origin of the analytic method

The philosophical school of neo-Aristotelianism began among Roman Catholics, for example, the universitiesPadua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

and Coimbra

Coimbra (, also , , or ) is a city and a municipality in Portugal. The population of the municipality at the 2011 census was 143,397, in an area of .

The fourth-largest urban area in Portugal after Lisbon, Porto, and Braga, it is the largest cit ...

. However, it spread to Germany by the late 16th century, resulting in a distinctly Protestant system of metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

associated with humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

. This scholastic system of metaphysics held that abstract concepts could explain the world in clear, distinct terms. This influenced the character of the scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientifi ...

.Hägglund, Bengt, ''History of Theology''. trans. Lund, Gene, L. St. Louis: Concordia, 1968. p. 300.

Jacopo Zabarella

Giacomo (or Jacopo) Zabarella (5 September 1533 – 15 October 1589) was an Italian Aristotelian philosopher and logician.

Life

Zabarella was born into a noble Paduan family. He received a humanist education and entered the University of Padua ...

, a natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

from Padua, taught that one could begin with a goal in mind and then explain ways to reach the goal. Although this was a scientific concept that Lutherans did not feel theology had to follow, by the beginning of the 17th century, Lutheran theologian Balthasar Mentzer

Balthazar, or variant spellings, may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Balthazar'' (novel), by Lawrence Durrell, 1958

* ''Balthasar'', an 1889 book by Anatole France

* '' Professor Balthazar'', a Croatian animated TV series, 1967-1978 ...

attempted to explain theology in the same way. Beginning with God as the goal, he explained the doctrine of man, the nature of theology, and the way man can attain eternal happiness with God. This form of presentation, called the analytic method, replaced the loci method used by Melancthon in his ''Loci Communes''. This method made the presentation of theology more uniform, as each theologian could present Christian teaching as the message of salvation and the way to attain this salvation.Hägglund, Bengt, ''History of Theology''. trans. Lund, Gene, L. St. Louis: Concordia, 1968. p. 301.

Flourishing of the analytic and synthetic methods

After the time of Johann Gerhard, Lutherans lost their attitude that philosophy was antagonistic to theology. Instead, Lutheran dogmaticians usedsyllogistic

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

...

arguments and the philosophical terms common in the neo-Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics. It covers the treatment of the so ...

of the time to make fine distinctions and enhance the precision of their theological method.Preus, Robert. The Inspiration of Scripture: A Study of the Theology of the 17th Century Lutheran Dogmaticians

'' London: Oliver and Boyd, 1957. Scholastic Lutheran theologians engaged in a twofold task. First, they collected texts, arranged them, supported them with arguments, and gave rebuttals based on the theologians before them. Second, they completed their process by going back to the pre-Reformation scholastics in order to gather additional material which they assumed the Reformation also accepted. Even though the Lutheran scholastic theologians added their own criticism to the pre-Reformation scholastics, they still had an important influence. Mainly, this practice served to separate their theology from direct interaction with Scripture. However, their theology was still built on Scripture as an authority that needed no external validation. Their scholastic method was intended to serve the purpose of their theology. Some dogmaticians preferred to use the synthetic method, while others used the analytic method, but all of them allowed Scripture to determine the form and content of their statements.

Abuse of the methods

Some Lutheran scholastic theologians, for example, Johann Gerhard, used exegetical theology along with Lutheran scholasticism. However, in Calov, even his exegesis is dominated by his use of the analytic method With Johann Friedrich König and his studentJohannes Andreas Quenstedt

Johannes Andreas Quenstedt (13 August 1617 – 22 May 1688) was a German Lutheran dogmatician in the Lutheran scholastic tradition.

Quenstedt was born at Quedlinburg, a nephew of Johann Gerhard. He was educated at the University of Helmstedt, 16 ...

, scholastic Lutheran theology reached its zenith. However the 20th century Lutheran scholar Robert Preus

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

was of the opinion that König went overboard with the scholastic method by overloading his small book, ''Theologia Positiva Acroamatica'' with Aristotelian distinctions. He noted that the scholastic method was inherently loaded with pitfalls. In particular, dogmaticians sometimes established cause and effect

Causality (also referred to as causation, or cause and effect) is influence by which one event, process, state, or object (''a'' ''cause'') contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (an ''effect'') where the cau ...

relationships without suitable links. When dogmaticians forced mysteries of the faith to fit into strict cause and effect relationships, they created "serious inconsistencies". In addition, sometimes they drew unneeded or baseless conclusions from the writings of their opponents, which not only was unproductive, but also harmed their own cause more than that of their rivals. Later orthodox dogmaticians tended to have an enormous number of artificial distinctions.

Merits of the methods

On the other hand, the Lutheran scholastic method, although often tedious and complicated, managed to largely avoid vagueness and the fallacy ofequivocation

In logic, equivocation ("calling two different things by the same name") is an informal fallacy resulting from the use of a particular word/expression in multiple senses within an argument.

It is a type of ambiguity that stems from a phrase havin ...

. As a result, their writings are understandable and prone to misrepresentation only by those entirely opposed to their theology. The use of scholastic philosophy also made Lutheran orthodoxy more intellectually rigorous. Theological questions could be resolved in a clean cut, even scientific, manner. The use of philosophy gave orthodox Lutheran theologians better tools to pass on their tradition than were otherwise available. It is also worth noting that it was only after neo-Aristotelian philosophical methods were ended that orthodox Lutheranism came to be criticized as austere, non-Christian formalism.

Distinction between scholastic theology and method

The term “scholasticism” is used to indicate both thescholastic theology

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

that arose during the pre-Reformation Church and the methodology associated with it. While Lutherans reject the theology of the scholastics, some accept their method. Jacobs, Henry Eyster. �Scholasticism in the Luth. Church

” ''Lutheran Cyclopedia.'' New York: Scribner, 1899. pp. 434–5.

Henry Eyster Jacobs

Henry Eyster Jacobs (November 10, 1844 – July 7, 1932) was an American religious educator, Biblical commentator and Lutheran theologian.

Biography

Jacobs was born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the son of professor Michael and Juliana M (Ey ...

writes of the scholastic method:

:The method is the application of the most rigorous appliances of logic to the formulation and analysis of theological definitions. The method ''per se'' cannot be vicious, as sound logic always must keep within its own boundaries. It became false, when logic, as a science that has only to do with the natural, and with the supernatural only so far as it has been brought, by revelation, within the sphere of natural apprehension, undertakes not only to be the test of the supernatural, but to determine all of its relations.

Worship and spirituality

Congregations maintained the fullMass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

rituals in their normal worship as suggested by Luther. In his ''Hauptgottesdienst'' (principal service of worship), Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

was celebrated on each Sunday and festival. The traditional parts of the service were retained and, sometimes, even incense

Incense is aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremony. It may also b ...

was also used. Services were conducted in vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

language, but in Germany, Latin was also present in both the Ordinary and Proper

Proper may refer to:

Mathematics

* Proper map, in topology, a property of continuous function between topological spaces, if inverse images of compact subsets are compact

* Proper morphism, in algebraic geometry, an analogue of a proper map for ...

parts of the service. This helped students maintain their familiarity with the language. As late as the time of Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

, churches in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

still heard Polyphonic

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords, ...

motets in Latin, Latin Glorias, chant

A chant (from French ', from Latin ', "to sing") is the iterative speaking or singing of words or sounds, often primarily on one or two main pitches called reciting tones. Chants may range from a simple melody involving a limited set of n ...

ed Latin collect

The collect ( ) is a short general prayer of a particular structure used in Christian liturgy.

Collects appear in the liturgies of Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, Methodist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian churches, among othe ...

s and The Creed sung in Latin by the choir.

Church music flourished and this era is considered as a "golden age" of Lutheran hymnody. Some hymnwriters include Philipp Nicolai

Philipp Nicolai (10 August 1556 – 26 October 1608) was a German Lutheran pastor, poet, and composer. He is most widely recognized as a hymnodist.

Biography

Philipp Nicolai was born at Mengeringhausen in Waldeck, Hesse, Germany where his ...

, Johann Heermann

Johann Heermann (11 October 158517 February 1647) was a German poet and hymnodist. He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 26 October with Philipp Nicolai and Paul Gerhardt.

Life

Heermann was born in Raudten ...

, Johann von Rist and Benjamin Schmolck in Germany, Haquin Spegel in Sweden, Thomas Hansen Kingo

Thomas Hansen Kingo (15 December 1634 – 14 October 1703 Odense) was a Danish bishop, poet and hymn-writer born at Slangerup, near Copenhagen. His work marked the high point of Danish baroque poetry.

His father was a weaver of modest means ...

in Denmark, Petter Dass

Petter Pettersen Dass (c. 1647 – 17 August 1707) was a Lutheran priest and the foremost Norwegian poet of his generation, writing both baroque hymns and topographical poetry.

Biography

He was born at Northern Herøy ( Dønna), Nordland, N ...

in Norway, Hallgrímur Pétursson

Hallgrímur Pétursson (1614 – 27 October 1674) was an Icelandic poet and a minister at Hvalsneskirkja and Saurbær in Hvalfjörður. Being one of the most prominent Icelandic poets, the Hallgrímskirkja in Reykjavík and the Hallgrímskirk ...

in Iceland, and Hemminki Maskulainen in Finland. The most famous orthodox Lutheran hymnwriter is Paul Gerhardt

Paul Gerhardt (12 March 1607 – 27 May 1676) was a German theologian, Lutheran minister and hymnodist.

Biography

Gerhardt was born into a middle-class family at Gräfenhainichen, a small town between Halle and Wittenberg. His father died in ...

. Prominent church musicians and composers include Michael Praetorius

Michael Praetorius (probably 28 September 1571 – 15 February 1621) was a German composer, organist, and music theorist. He was one of the most versatile composers of his age, being particularly significant in the development of musical forms ba ...

, Melchior Vulpius

Melchior Vulpius (c. 1570 in Wasungen – 7 August 1615 in Weimar) was a German singer and composer of church music.

Vulpius came from a poor craftsman's family. He studied at the local school in Wasungen (in Thuringia) with Johannes St ...

, Johann Hermann Schein, Heinrich Schütz

Heinrich Schütz (; 6 November 1672) was a German early Baroque composer and organist, generally regarded as the most important German composer before Johann Sebastian Bach, as well as one of the most important composers of the 17th century. He ...

, Johann Crüger

Johann Crüger (9 April 1598 – 23 February 1662) was a German composer of well-known hymns. He was also the editor of the most widely used Lutheran hymnal of the 17th century, '' Praxis pietatis melica''.

Early life and education

Crüger was b ...

, Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal a ...

and Bach. Generally, the 17th century was a more difficult time than the earlier period of Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, due in part to the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of batt ...

. Finland suffered a severe famine in 1696-1697 as part of what is now called the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Ma ...

, and almost one third of the population died. This struggle to survive can often be seen in hymns and devotional writings.

Evaluation

The era of Lutheran orthodoxy is not well known, and it has been very often looked at only through the view ofliberal theology

Religious liberalism is a conception of religion (or of a particular religion) which emphasizes personal and group liberty and rationality. It is an attitude towards one's own religion (as opposed to criticism of religion from a secular position ...

and pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christian life, including a social concern for the needy an ...

and thus underestimated. The wide gap between the theology of Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

and rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

has sometimes limited later theological neo-Lutheran

Neo-Lutheranism was a 19th-century revival movement within Lutheranism which began with the Pietist-driven '' Erweckung,'' or ''Awakening'', and developed in reaction against theological rationalism and pietism. This movement followed the Old Lu ...

and confessional Lutheran

Confessional Lutheranism is a name used by Lutherans to designate those who believe in the doctrines taught in the ''Book of Concord'' of 1580 (the Lutheran confessional documents) in their entirety. Confessional Lutherans maintain that faithfulne ...

attempts to understand and restore Lutheran orthodoxy.

More recently, a number of social historians, as well as historical theologians, have brought Lutheran orthodoxy to the forefront of their research. These scholars have expanded the understanding of Lutheran orthodoxy to include topics such as preaching and catechesis, devotional literature, popular piety, religious ritual, music and hymnody, and the concerns of cultural and political historians.

The most significant theologians of Orthodoxy can be said to be Martin Chemnitz and Johann Gerhard. Lutheran orthodoxy can also be reflected in such rulers as Ernst I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Altenburg

Ernest I, called "Ernest the Pious" (25 December 1601 – 26 March 1675), was a duke of Saxe-Gotha and Saxe-Altenburg. The duchies were later merged into Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.

He was the ninth but sixth surviving son of Johann II, Duke of Saxe ...

and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

.

See also

* '' Loci Theologici'' * Protestant scholasticism * Reformed orthodoxy *Scholastic Lutheran Christology

Scholastic Lutheran Christology is the orthodox Lutheran theology of Jesus, developed using the methodology of Lutheran scholasticism.

On the general basis of the Chalcedonian christology and following the

indications of the Scriptures as t ...

References

External links

Sketch of the dogmaticians of Lutheran orthodoxy

from ''The Doctrinal Theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church'' by Heinrich Schmid

Lutheran Legacy

{{Authority control

Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

Orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Church ...

Christianity in the early modern period

Christian theological movements

Scholasticism