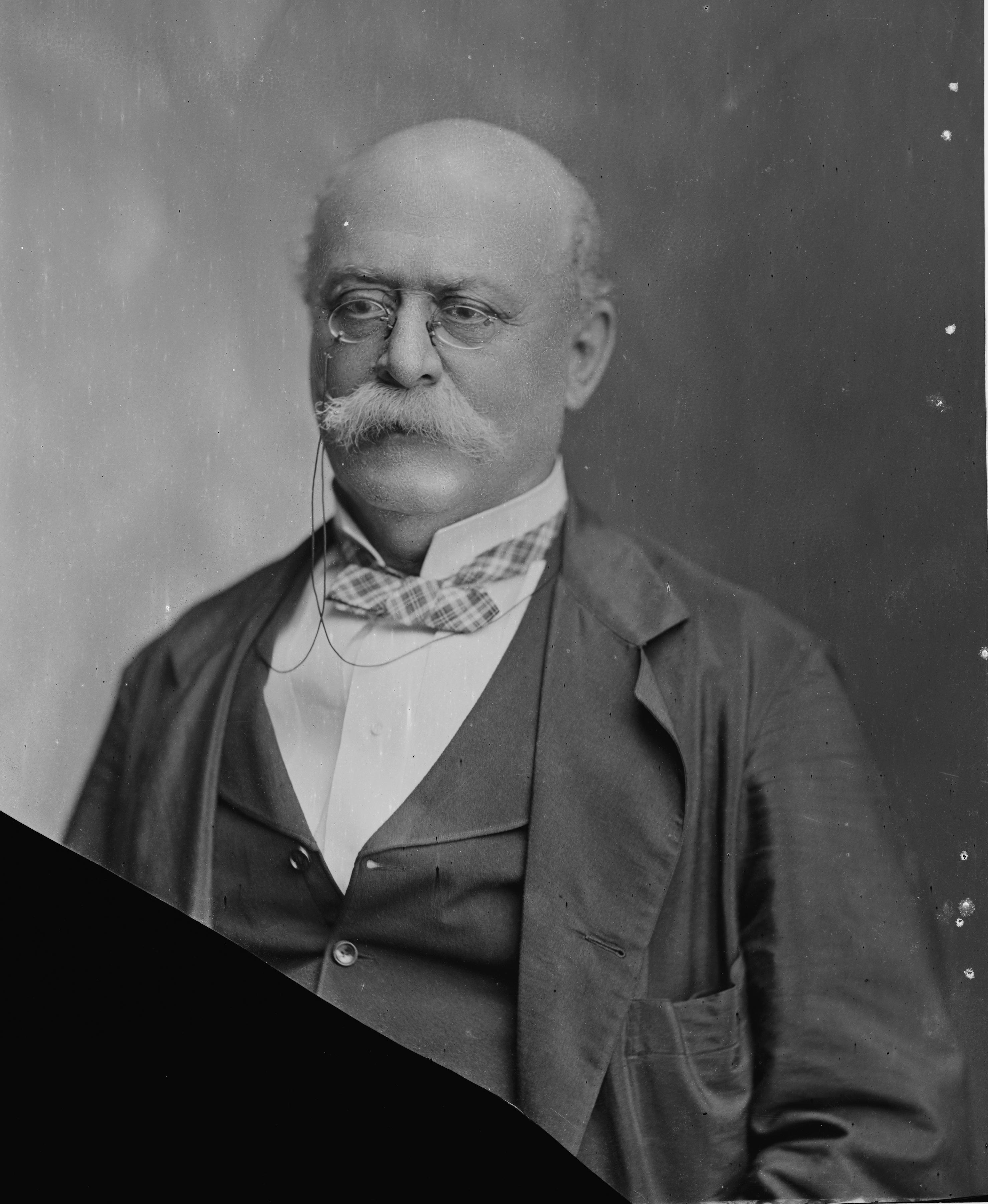

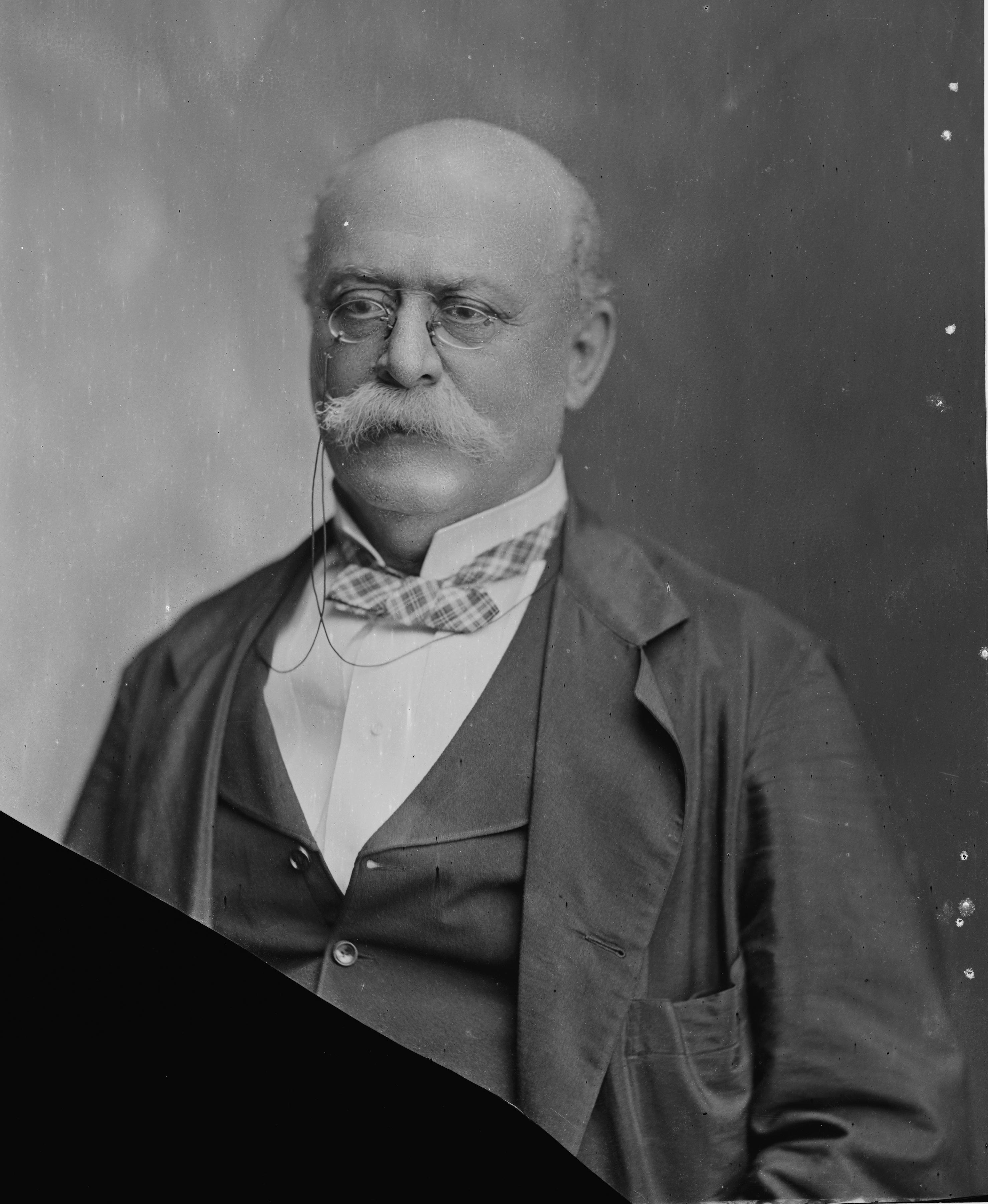

Louis M. Goldsborough on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough (February 18, 1805 – February 20, 1877) was a

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough (February 18, 1805 – February 20, 1877) was a

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough (February 18, 1805 – February 20, 1877) was a

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough (February 18, 1805 – February 20, 1877) was a rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He held several sea commands during the Civil War, including that of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic ...

. He was also noted for contributions to nautical scientific research.

His younger brother, John R. Goldsborough, was also a U.S. Navy officer who served during the Civil War and who later became a commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

.

Biography

Louis Malesherbes Goldsborough was born in Washington, D.C., in 1805, the son of a chief clerk at theUnited States Department of the Navy

The United States Department of the Navy (DoN) is one of the three military departments within the Department of Defense of the United States of America. It was established by an Act of Congress on 30 April 1798, at the urging of Secretary o ...

. He was appointed midshipman in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

by Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Paul Hamilton on June 28, 1812. At the time of his appointment, he was seven years old, and Goldsborough did not actually begin serving until February 13, 1816, when he reported for duty at the Washington Navy Yard

The Washington Navy Yard (WNY) is the former shipyard and ordnance plant of the United States Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. It is the oldest shore establishment of the U.S. Navy.

The Yard currently serves as a ceremonial and administrat ...

.

In 1831 Goldsborough married Elizabeth Wirt, daughter of William Wirt, U.S. Attorney General from 1817 to 1829. Together, they had three children: William, Louis, and Elizabeth.

In 1833, after helping lead German emigrants to Wirt's Estates near Monticello, Florida

Monticello ( ) is the only city in Jefferson County, Florida, United States. The population was 2,506 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Jefferson County. The city is named after Monticello, the estate of the county's namesake, Thomas ...

, Goldsborough took leave from the Navy to command a steamboat expedition, and later mounted volunteers in the Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

.

Naval service

During the Aegean Anti-Piracy Campaign, Goldsborough led a four-boat night expedition from ''Porpoise'' in October 1827 to rescue British merchantbrig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the latter part ...

''Comet'' from Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

s. In 1830 he was appointed first officer in charge of the newly created Depot of Charts and Instruments at Washington, the crude beginning of the United States Hydrographic Office

The United States Hydrographic Office prepared and published maps, charts, and nautical books required in navigation.

The office was established by an act of 21 June 1866 as part of the Bureau of Navigation, Department of the Navy.

It was trans ...

. Goldsborough suggested creation of the depot and initiated the collection and centralization of the instruments, books and charts that were scattered among several Navy yards. After two years he was relieved by Lieutenant Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

.

After cruising the Pacific in the frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

''United States'', he participated in the bombardment of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

in ''Ohio'' during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. He served consecutively as: commander of a detachment in the expedition against Tuxpan

Tuxpan (or Túxpam, fully Túxpam de Rodríguez Cano) is both a municipality and city located in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The population of the city was 78,523 and of the municipality was 134,394 inhabitants, according to the INEGI censu ...

; senior officer of a commission which explored California and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

(1849–1850); superintendent of the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

(1853–1857); and commander of the Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

Squadron (1859–1861).

Civil War service

Goldsborough was given command of theAtlantic Blockading Squadron

The Atlantic Blockading Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy created in the early days of the American Civil War to enforce the Union blockade of the ports of the Confederate States. It was formed in 1861 and split up the same year for th ...

in September 1861, relieving Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham

Rear Admiral Silas Horton Stringham (November 7, 1798 – February 7, 1876) was an officer of the United States Navy who saw active service during the War of 1812, the Second Barbary War, and the Mexican–American War, and who commanded the Atla ...

. In October of that year the Atlantic squadron was split into the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic ...

and South Atlantic Blockading Squadron

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

The blockade was proclaimed by President Abraham Lincoln in April 1861, and required the monitoring of of Atlantic ...

; Goldsborough took command of the North squadron, and Flag Officer Samuel Francis DuPont

Samuel Francis Du Pont (September 27, 1803 – June 23, 1865) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy, and a member of the prominent Du Pont family. In the Mexican–American War, Du Pont captured San Diego, and was made commander of the Ca ...

assumed command of the South squadron. On January 3, 1862, both officers were promoted to the newly created rank of Flag Officer (equivalent to the rank of Commodore which would be created 5 months later). During his command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which he commanded from its inception to September 1862, he led his fleet off North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, where in cooperation with troops under General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, he captured Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina, United States. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of Engl ...

and destroyed a small Confederate fleet.

Peninsula Campaign

After aiding the capture of Roanoke Island, Goldsborough and his command were sent toHampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic ...

at the request of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

to help protect Union forces landing on the Virginia Peninsula at the start of the Peninsula Campaign. Goldsborough refused to be placed under McClellan's direct command, telling Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox that he would instead ''cooperate'' with McClellan. After sending six of his vessels to attack the Gloucester Point batteries, Goldsborough withdrew them, saying the area was too dangerous for his ships—even though none of them sustained any damage—and fearful of a return appearance by CSS ''Virginia'', which had laid waste to a Union naval force in Hampton Roads while Goldsborough was at Roanoke Island.

At the start of the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

, Goldsborough was asked again, this time by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, to come to McClellan's aid. Goldsborough continued to hold back his fleet, forcing Lincoln to accept a recommendation by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878), nicknamed "Father Neptune", was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was awarded after supporting Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed ...

to detach ships under Goldsborough's command and place them under Commodore Charles Wilkes

Charles Wilkes (April 3, 1798 – February 8, 1877) was an American naval officer, ship's captain, and explorer. He led the United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842).

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), he commanded ' during the ...

, who as a lieutenant had relieved Goldsborough at the Depot of Charts and Instruments (see above), and who would report directly to Welles. This move, coupled with newspaper accounts critical of the Navy, so seriously hurt Goldsborough that he requested that he be relieved. He was promoted to rear admiral in August 1862, and in September passed command of the squadron to Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee. Goldsborough would finish the war performing administrative duties in Washington, D.C.

Post-Civil War service and death

In June 1865, Goldsborough became the first commander of theEuropean Squadron

The European Squadron, also known as the European Station, was a part of the United States Navy in the late 19th century and the early 1900s. The squadron was originally named the Mediterranean Squadron and renamed following the American Civil Wa ...

, formerly the Mediterranean Squadron. In 1868, Goldsborough returned to Washington and took command of the Washington Navy Yard, a position he held until he retired in 1873.

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star " admiral" rank. It is often rega ...

Louis M. Goldsborough died in Washington, D.C. on February 20, 1877.

Dates of rank

*Midshipman – June 18, 1812 *Lieutenant – January 13, 1825 *Commander – September 8, 1841 *Captain – September 14, 1855 *Flag Officer – January 3, 1862 *Rear Admiral – July 16, 1862 *Retired List – October 6, 1873 *Died – February 20, 1877Namesakes

The United States Navy has named three ships USS ''Goldsborough'' in honor of Admiral Goldsborough.See also

*List of Superintendents of the United States Naval Academy

The Superintendent of the United States Naval Academy is its commanding officer. The position is a statutory office (), and is roughly equivalent to the chancellor or president of an American civilian university. The officer appointed is, by tradi ...

References

: {{DEFAULTSORT:Goldsborough, Louis M. 1805 births 1877 deaths Union Navy admirals United States Navy rear admirals Superintendents of the United States Naval Academy United States Navy personnel of the Mexican–American War People of Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War