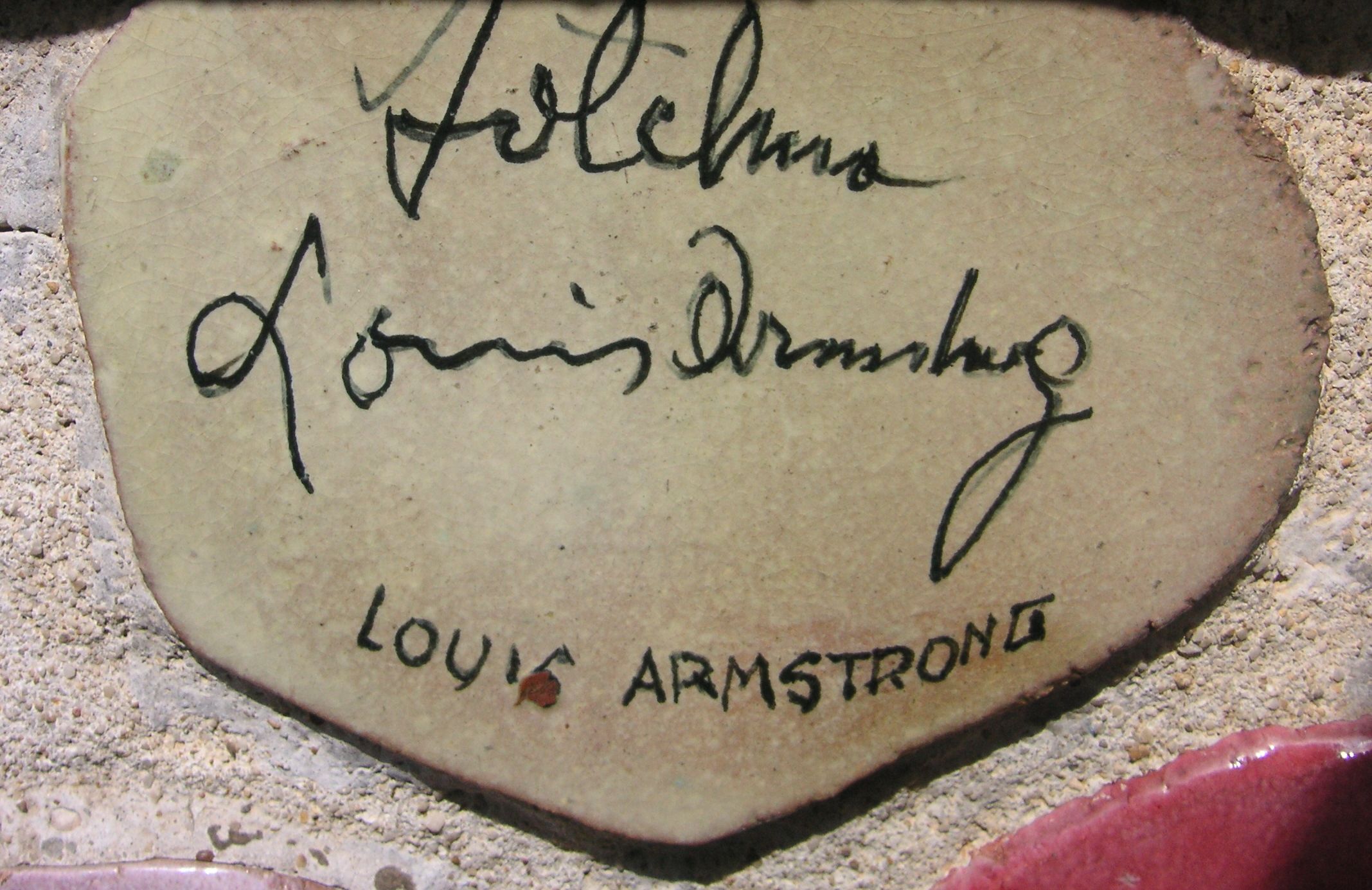

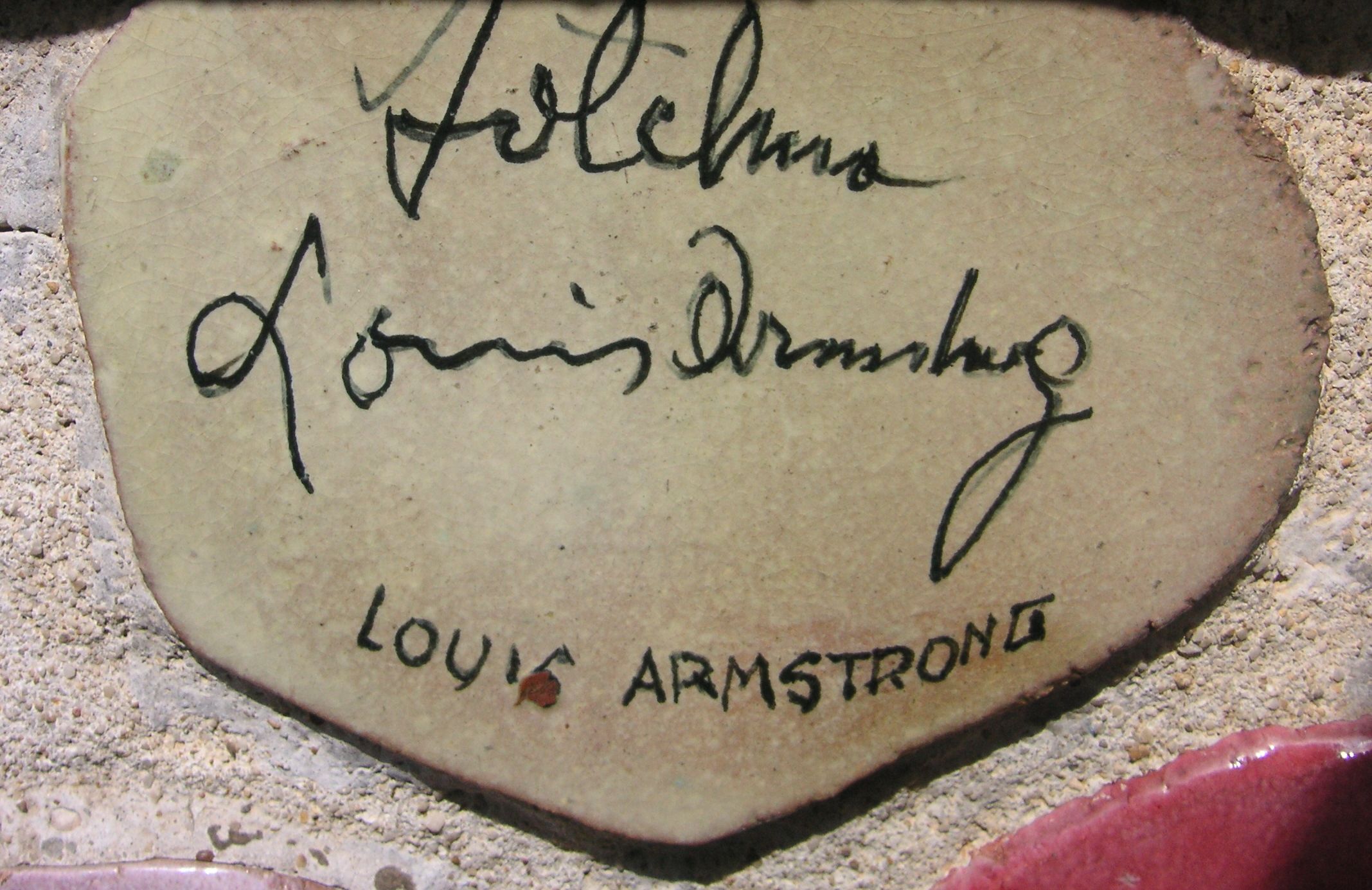

Louis Armstong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American

Armstrong was born in on August 4, 1901. His parents were Mary Estelle "Mayann" Albert and William Armstrong. Mary Albert was from

Armstrong was born in on August 4, 1901. His parents were Mary Estelle "Mayann" Albert and William Armstrong. Mary Albert was from

Early in his career, Armstrong played in brass bands and

Early in his career, Armstrong played in brass bands and

The Hot Five included

The Hot Five included

The Great Depression of the early 1930s was especially hard on the jazz scene. The Cotton Club closed in 1936 after a long downward spiral and many musicians stopped playing altogether as club dates evaporated. Bix Beiderbecke died and Fletcher Henderson's band broke up. King Oliver made a few records but otherwise struggled.

The Great Depression of the early 1930s was especially hard on the jazz scene. The Cotton Club closed in 1936 after a long downward spiral and many musicians stopped playing altogether as club dates evaporated. Bix Beiderbecke died and Fletcher Henderson's band broke up. King Oliver made a few records but otherwise struggled.

After spending many years on the road, Armstrong settled permanently in Queens, New York in 1943, in contentment with his fourth wife, Lucille. Although subject to the vicissitudes of

After spending many years on the road, Armstrong settled permanently in Queens, New York in 1943, in contentment with his fourth wife, Lucille. Although subject to the vicissitudes of

By the 1950s, Armstrong was a widely beloved American icon and cultural ambassador who commanded an international fanbase. However, a growing generation gap became apparent between him and the young jazz musicians who emerged in the postwar era such as

By the 1950s, Armstrong was a widely beloved American icon and cultural ambassador who commanded an international fanbase. However, a growing generation gap became apparent between him and the young jazz musicians who emerged in the postwar era such as

In the 1960s, he toured

In the 1960s, he toured

Armstrong was performing at the Brick House in

Armstrong was performing at the Brick House in

Armstrong was colorful and charismatic. His autobiography vexed some biographers and historians because he had a habit of telling tales, particularly about his early childhood when he was less scrutinized, and his embellishments lack consistency.Bergreen (1997), pp. 7–11.

In addition to being an entertainer, Armstrong was a leading personality. He was beloved by an American public that usually offered little access beyond their public celebrity to even the greatest

Armstrong was colorful and charismatic. His autobiography vexed some biographers and historians because he had a habit of telling tales, particularly about his early childhood when he was less scrutinized, and his embellishments lack consistency.Bergreen (1997), pp. 7–11.

In addition to being an entertainer, Armstrong was a leading personality. He was beloved by an American public that usually offered little access beyond their public celebrity to even the greatest

The nicknames "Satchmo" and "Satch" are short for "Satchelmouth". The nickname origin is uncertain. The most common tale that biographers tell is the story of Armstrong as a young boy in New Orleans dancing for pennies. He scooped the coins off the street and stuck them into his mouth to prevent bigger children from stealing them. Someone dubbed him "satchel mouth" for his mouth acting as a satchel. Another tale is that because of his large mouth, he was nicknamed "satchel mouth" which was shortened to "Satchmo".

Early on he was also known as "Dipper", short for "Dippermouth", a reference to the piece ''Dippermouth Blues'' and something of a riff on his unusual

The nicknames "Satchmo" and "Satch" are short for "Satchelmouth". The nickname origin is uncertain. The most common tale that biographers tell is the story of Armstrong as a young boy in New Orleans dancing for pennies. He scooped the coins off the street and stuck them into his mouth to prevent bigger children from stealing them. Someone dubbed him "satchel mouth" for his mouth acting as a satchel. Another tale is that because of his large mouth, he was nicknamed "satchel mouth" which was shortened to "Satchmo".

Early on he was also known as "Dipper", short for "Dippermouth", a reference to the piece ''Dippermouth Blues'' and something of a riff on his unusual

In his early years, Armstrong was best known for his virtuosity with the cornet and trumpet. Along with his "clarinet-like figurations and high notes in his cornet solos", he was also known for his "intense rhythmic 'swing', a complex conception involving ... accented upbeats, upbeat to downbeat slurring, and complementary relations among rhythmic patterns." The most lauded recordings on which Armstrong plays trumpet include the Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions, as well as those of the

In his early years, Armstrong was best known for his virtuosity with the cornet and trumpet. Along with his "clarinet-like figurations and high notes in his cornet solos", he was also known for his "intense rhythmic 'swing', a complex conception involving ... accented upbeats, upbeat to downbeat slurring, and complementary relations among rhythmic patterns." The most lauded recordings on which Armstrong plays trumpet include the Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions, as well as those of the

During his long career he played and sang with some of the most important instrumentalists and vocalists of the time, including Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines,

During his long career he played and sang with some of the most important instrumentalists and vocalists of the time, including Bing Crosby, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines,  In the week beginning May 9, 1964, his recording of the song " Hello, Dolly!" went to number one. An album of the same title was quickly created around the song, and also shot to number one, knocking

In the week beginning May 9, 1964, his recording of the song " Hello, Dolly!" went to number one. An album of the same title was quickly created around the song, and also shot to number one, knocking

In 1937, Armstrong was the first African American to host a The Fleischmann's Yeast Hour#Guests, nationally broadcast radio show. In 1969, he had a cameo role in Gene Kelly's film version of '' Hello, Dolly!'' as the bandleader Louis where he sang the title song with actress

In 1937, Armstrong was the first African American to host a The Fleischmann's Yeast Hour#Guests, nationally broadcast radio show. In 1969, he had a cameo role in Gene Kelly's film version of '' Hello, Dolly!'' as the bandleader Louis where he sang the title song with actress

Against his doctor's advice, Armstrong played a two-week engagement in March 1971 at the Waldorf-Astoria's Empire Room. At the end of it, he was hospitalized for a myocardial infarction, heart attack. He was released from the hospital in May, and quickly resumed practicing his trumpet playing. Still hoping to get back on the road, Armstrong died of a heart attack in his sleep on July 6, 1971, two days after celebrating his alleged 71st birthday, and a month before his actual 70th birthday. He was residing in Corona, Queens, New York City, at the time of his death. He was interred in Flushing Cemetery, Flushing, Queens, Flushing, in Queens, New York City.

His honorary pallbearers included Bing Crosby,

Against his doctor's advice, Armstrong played a two-week engagement in March 1971 at the Waldorf-Astoria's Empire Room. At the end of it, he was hospitalized for a myocardial infarction, heart attack. He was released from the hospital in May, and quickly resumed practicing his trumpet playing. Still hoping to get back on the road, Armstrong died of a heart attack in his sleep on July 6, 1971, two days after celebrating his alleged 71st birthday, and a month before his actual 70th birthday. He was residing in Corona, Queens, New York City, at the time of his death. He was interred in Flushing Cemetery, Flushing, Queens, Flushing, in Queens, New York City.

His honorary pallbearers included Bing Crosby,

''Underneath a Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall''

. Bloomsbury Publishers, 2002.

trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

er and vocalist

Singing is the act of creating musical sounds with the voice. A person who sings is called a singer, artist or vocalist (in jazz and/or popular music). Singers perform music (arias, recitatives, songs, etc.) that can be sung with or withou ...

. He was among the most influential figures in jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a m ...

. His career spanned five decades and several eras in the history of jazz.

Armstrong was born and raised in . Coming to prominence in the 1920s as an inventive trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

and cornet player, Armstrong was a foundational influence in jazz, shifting the focus of the music from collective improvisation to solo performance. Around 1922, he followed his mentor, Joe "King" Oliver

Joseph Nathan "King" Oliver (December 19, 1881 – April 8/10, 1938) was an American jazz cornet player and bandleader. He was particularly recognized for his playing style and his pioneering use of mutes in jazz. Also a notable composer, he wr ...

, to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

to play in the . In Chicago, he spent time with other popular jazz musicians, reconnecting with his friend Bix Beiderbecke and spending time with Hoagy Carmichael

Hoagland Howard Carmichael (November 22, 1899 – December 27, 1981) was an American musician, composer, songwriter, actor and lawyer. Carmichael was one of the most successful Tin Pan Alley songwriters of the 1930s, and was among the first ...

and Lil Hardin

Lillian Hardin Armstrong (née Hardin; February 3, 1898 – August 27, 1971) was an American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, singer, and bandleader. She was the second wife of Louis Armstrong, with whom she collaborated on many recordings in ...

. He earned a reputation at "cutting contest

A cutting contest was a musical battle between various stride piano players from the 1920s to the 1940s, and to a lesser extent in improvisation contests on other jazz instruments during the swing era.

Up to the present time, the expression ''cu ...

s", and his fame reached band leader Fletcher Henderson. Henderson persuaded Armstrong to come to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, where he became a featured and musically influential band soloist and recording artist. Hardin became Armstrong's second wife and they returned to Chicago to play together and then he began to form his own "Hot" jazz bands. After years of touring, he settled in Queens, New York

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

, and by the 1950s, he was a national musical icon, assisted in part, by his appearances on radio and in film and television, in addition to his concerts.

With his instantly recognizable rich, gravelly voice, Armstrong was also an influential singer and skillful improviser, bending the lyrics and melody of a song. He was also skilled at scat singing

In vocal jazz, scat singing is vocal improvisation with wordless vocables, nonsense syllables or without words at all. In scat singing, the singer improvises melodies and rhythms using the voice as an instrument rather than a speaking medium. ...

. Armstrong is renowned for his charismatic stage presence and voice as well as his trumpet playing. By the end of Armstrong's life, his influence had spread to popular music in general. Armstrong was one of the first popular African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

entertainers to "cross over" to wide popularity with white (and international) audiences. He rarely publicly politicized his race, to the dismay of fellow African Americans, but took a well-publicized stand for desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

in the Little Rock crisis

Little is a synonym for small size and may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Little'' (album), 1990 debut album of Vic Chesnutt

* ''Little'' (film), 2019 American comedy film

*The Littles, a series of children's novels by American author John P ...

. He was able to access the upper echelons of American society at a time when this was difficult for black men.

Armstrong appeared in films such as ''High Society

High society, sometimes simply society, is the behavior and lifestyle of people with the highest levels of wealth and social status. It includes their related affiliations, social events and practices. Upscale social clubs were open to men based ...

'' (1956) alongside Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly

Grace Patricia Kelly (November 12, 1929 – September 14, 1982) was an American actress who, after starring in several significant films in the early to mid-1950s, became Princess of Monaco by marrying Prince Rainier III in April 1956.

Kelly ...

, and Frank Sinatra, and '' Hello, Dolly!'' (1969) starring Barbra Streisand

Barbara Joan "Barbra" Streisand (; born April 24, 1942) is an American singer, actress and director. With a career spanning over six decades, she has achieved success in multiple fields of entertainment, and is among the few performers awar ...

. He received many accolades including three Grammy Award

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by many as the most pr ...

nominations and a win for his vocal performance of '' Hello, Dolly!'' in 1964. In 2017, he was posthumously inducted into the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Early life

Armstrong was born in on August 4, 1901. His parents were Mary Estelle "Mayann" Albert and William Armstrong. Mary Albert was from

Armstrong was born in on August 4, 1901. His parents were Mary Estelle "Mayann" Albert and William Armstrong. Mary Albert was from Boutte, Louisiana

Boutte is a census-designated place (CDP) in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 3,075 at the 2010 census, and 3,054 in 2020.

Geography

Boutte is located at (29.901060, -90.386434).

According to the United States C ...

, and gave birth at home when she was about sixteen. Less than a year and a half later, they had a daughter, Beatrice "Mama Lucy" Armstrong (1903-1987), who was raised by Albert. William Armstrong abandoned the family shortly thereafter.Giddins (2001), pp. 2223

Louis Armstrong was raised by his grandmother until the age of five when he was returned to his mother. He spent his youth in poverty in a rough neighborhood known as The Battlefield, on the southern section of Rampart Street

Rampart Street (french: rue du Rempart) is a historic avenue located in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The section of Rampart Street downriver from Canal Street is designated as North Rampart Street, which forms the inland or northern border of the Fr ...

. At six he attended the Fisk School for Boys, a school that accepted black children in the racially segregated system of New Orleans.

At the age of 6, Armstrong lived with his mother and sister and worked for the Karnoffskys, a family of Lithuanian Jews

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks () are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent are ...

, at their home. He would help their two sons, Morris and Alex, collect "rags and bones" and deliver coal. In 1969, while recovering from heart and kidney problems at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City, Armstrong wrote ''Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, LA., the year of 1907'', a memoir describing his time working for the Karnofsky family.

Armstrong writes about singing "Russian Lullaby" with the Karnofsky family when their baby son David was put to bed and credits the family with teaching him to sing "from the heart." Curiously, Armstrong quotes lyrics for it that appear to be the same as the "Russian Lullaby," copyrighted by Irving Berlin

Irving Berlin (born Israel Beilin; yi, ישראל ביילין; May 11, 1888 – September 22, 1989) was a Russian-American composer, songwriter and lyricist. His music forms a large part of the Great American Songbook.

Born in Imperial Russ ...

in 1927, about twenty years after Armstrong remembered singing it as a child. Gary Zucker, Armstrong's doctor at Beth Israel hospital in 1969, shared Berlin's song lyrics with him, and Armstrong quoted them in the memoir. This inaccuracy may simply be because he wrote the memoir over 60 years after the events described. Regardless, the Karnoffskys treated Armstrong extremely well. Knowing he lived without a father, they fed and nurtured him.

In his memoir, ''Louis Armstrong + the Jewish Family in New Orleans, La., the Year of 1907'', he described his discovery that this family was also subject to discrimination by "other white folks" who felt that they were better than Jews: "I was only seven years old but I could easily see the ungodly treatment that the white folks were handing the poor Jewish family whom I worked for." He wrote about what he learned from them: "how to live—real life and determination." His first musical performance may have been at the side of the Karnoffskys' junk wagon. To distinguish them from other hawkers, he tried playing a tin horn to attract customers. Morris Karnoffsky gave Armstrong an advance toward the purchase of a cornet from a pawn shop.

Armstrong wore a Star of David until the end of his life in memory of this family who had raised him.

When Armstrong was eleven, he dropped out of school.Bergreen (1997), pp. 27, 57–60. His mother moved into a one-room house on Perdido Street with Armstrong, Lucy, and her common-law husband, Tom Lee, next door to her brother Ike and his two sons. Armstrong joined a quartet of boys who sang in the streets for money. He also got into trouble. Cornetist Bunk Johnson

Willie Gary "Bunk" Johnson (December 27, 1879 – July 7, 1949) was an American prominent jazz trumpeter in New Orleans. Johnson gave the year of his birth as 1879, although there is speculation that he may have been younger by as much as a dec ...

said he taught the eleven-year-old to play by ear at Dago Tony's honky tonk. (In his later years Armstrong credited King Oliver.) He said about his youth, "Every time I close my eyes blowing that trumpet of mine — I look right in the heart of good old New Orleans ... It has given me something to live for."

Borrowing his stepfather's gun without permission, he fired a blank into the air and was arrested on December 31, 1912. He spent the night at New Orleans Juvenile Court, then was sentenced the next day to detention at the Colored Waif's Home. Life at the home was spartan. Mattresses were absent; meals were often little more than bread and molasses. Captain Joseph Jones ran the home like a military camp and used corporal punishment.

Armstrong developed his cornet skills by playing in the band. Peter Davis, who frequently appeared at the home at the request of Captain Jones, became Armstrong's first teacher and chose him as bandleader. With this band, the thirteen-year-old Armstrong attracted the attention of Kid Ory

Edward "Kid" Ory (December 25, 1886 – January 23, 1973) was an American jazz composer, trombonist and bandleader. One of the early users of the glissando technique, he helped establish it as a central element of New Orleans jazz.

He was ...

.

On June 14, 1914, Armstrong was released into the custody of his father and his new stepmother, Gertrude. He lived in this household with two stepbrothers for several months. After Gertrude gave birth to a daughter, Armstrong's father never welcomed him, so he returned to his mother, Mary Albert. In her small home, he had to share a bed with his mother and sister. His mother still lived in The Battlefield, leaving him open to old temptations, but he sought work as a musician. He found a job at a dance hall owned by Henry Ponce, who had connections to organized crime. He met the six-foot tall drummer Black Benny, who became his guide and bodyguard. Around the age of fifteen, he pimped for a prostitute named Nootsy, but that relationship failed after she stabbed Armstrong in the shoulder and his mother choked her nearly to death.

He briefly studied shipping management at the local community college, but was forced to quit after being unable to afford the fees.Bergreen (1997), p. 44. While selling coal in Storyville, he heard spasm bands, groups that played music out of household objects. He heard the early sounds of jazz from bands that played in brothels and dance halls such as Pete Lala's, where King Oliver

Joseph Nathan "King" Oliver (December 19, 1881 – April 8/10, 1938) was an American jazz cornet player and bandleader. He was particularly recognized for his playing style and his pioneering use of mutes in jazz. Also a notable composer, he wr ...

performed.Bergreen (1997), pp. 4547.

Career

Riverboat education

Early in his career, Armstrong played in brass bands and

Early in his career, Armstrong played in brass bands and riverboat

A riverboat is a watercraft designed for inland navigation on lakes, rivers, and artificial waterways. They are generally equipped and outfitted as work boats in one of the carrying trades, for freight or people transport, including luxury un ...

s in New Orleans, first on an excursion boat in September 1918. He traveled with the band of Fate Marable

Fate Marable (December 2, 1890 – January 16, 1947) was an American jazz pianist and bandleader.

Early life

Marable was born in Paducah, Kentucky to James and Elizabeth Lillian (Wharton) Marable, a piano teacher. Fate had five siblings, includin ...

, which toured on the steamboat ''Sidney'' with the Streckfus Steamers line up and down the Mississippi River. Marable was proud of his musical knowledge, and he insisted that Armstrong and other musicians in his band learn sight reading

In music, sight-reading, also called ''a prima vista'' (Italian meaning "at first sight"), is the practice of reading and performing of a piece in a music notation that the performer has not seen or learned before. Sight-singing is used to descri ...

. Armstrong described his time with Marable as "going to the University", since it gave him a wider experience working with written arrangements. In 1919, Armstrong's mentor, King Oliver

Joseph Nathan "King" Oliver (December 19, 1881 – April 8/10, 1938) was an American jazz cornet player and bandleader. He was particularly recognized for his playing style and his pioneering use of mutes in jazz. Also a notable composer, he wr ...

decided to go north and resigned his position in Kid Ory's band; Armstrong replaced him. He also became second trumpet for the Tuxedo Brass Band The Tuxedo Brass Band, sometimes called the Original Tuxedo Brass Band, was one of the most highly regarded brass bands of New Orleans, Louisiana in the 1910s and 1920s.

It was led by Papa Celestin starting about 1910. Many noted jazz greats play ...

.

Throughout his riverboat experience, Armstrong's musicianship began to mature and expand. At twenty, he could read music. He became one of the first jazz musicians to be featured on extended trumpet solos, injecting his own personality and style. He also started singing in his performances.

Chicago recordings

In 1922, Armstrong moved to Chicago at the invitation of King Oliver, although Armstrong would return to New Orleans periodically for the rest of his life. Playing second cornet to Oliver in Oliver's Creole Jazz Band in the black-only Lincoln Gardens in Chicago's black neighborhood, he could make enough money to quit his day jobs. Although race relations were poor, Chicago was booming. The city had jobs for blacks making good wages at factories with some left over for entertainment. Oliver's band was among the most influential jazz bands in Chicago in the early 1920s. Armstrong lived luxuriously in his own apartment with his first private bath. Excited as he was to be in Chicago, he began his career-long pastime of writing letters to friends in New Orleans. Armstrong could blow two hundred high Cs in a row. As his reputation grew, he was challenged tocutting contest

A cutting contest was a musical battle between various stride piano players from the 1920s to the 1940s, and to a lesser extent in improvisation contests on other jazz instruments during the swing era.

Up to the present time, the expression ''cu ...

s by other musicians.

His first studio recordings were with Oliver for Gennett Records on April 56, 1923. They endured several hours on the train to remote Richmond, Indiana, and the band was paid little. The quality of the performances was affected by lack of rehearsal, crude recording equipment, bad acoustics, and a cramped studio. These early recordings were true acoustic, the band playing directly into a large funnel connected directly to the needle making the groove in the master recording. (Electrical recording was not invented until 1926 and Gennett installed it later.) Because Armstrong's playing was so loud, when he played next to Oliver, Oliver couldn't be heard on the recording. Armstrong had to stand fifteen feet away from Oliver, in a far corner of the room.

Lil Hardin

Lillian Hardin Armstrong (née Hardin; February 3, 1898 – August 27, 1971) was an American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, singer, and bandleader. She was the second wife of Louis Armstrong, with whom she collaborated on many recordings in ...

, who Armstrong would marry in 1924, urged Armstrong to seek more prominent billing and develop his style apart from the influence of Oliver. At her suggestion, Armstrong began to play classical music in church concerts to broaden his skills; and he began to dress more in more stylish attire to offset his girth. Her influence eventually undermined Armstrong's relationship with his mentor, especially concerning his salary and additional money that Oliver held back from Armstrong and other band members. Armstrong's mother, May Ann Albert, came to visit him in Chicago during the summer of 1923 after being told that Armstrong was "out of work, out of money, hungry, and sick"; Hardin located and decorated an apartment for her to live in while she stayed.

Fletcher Henderson Orchestra

Armstrong and Oliver parted amicably in 1924. Shortly afterward, Armstrong received an invitation to go to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, the top African-American band of the time. He switched to the trumpet to blend in better with the other musicians in his section. His influence on Henderson's tenor sax soloist,Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November 21, 1904 – May 19, 1969), nicknamed "Hawk" and sometimes "Bean", was an American jazz tenor saxophonist.Yanow, Scot"Coleman Hawkins: Artist Biography" AllMusic. Retrieved December 27, 2013. One of the first p ...

, can be judged by listening to the records made by the band during this period.

Armstrong adapted to the tightly controlled style of Henderson, playing trumpet and experimenting with the trombone. The other members were affected by Armstrong's emotional style. His act included singing and telling tales of New Orleans characters, especially preachers. The Henderson Orchestra played in prominent venues for white patrons only, including the Roseland Ballroom

The Roseland Ballroom was a multipurpose hall, in a converted ice skating rink, with a colorful ballroom dancing pedigree, in New York City's theater district, on West 52nd Street in Manhattan.

The venue, according to its website, accommodat ...

, with arrangements by Don Redman

Donald Matthew Redman (July 29, 1900 – November 30, 1964) was an American jazz musician, arranger, bandleader, and composer.

Biography

Redman was born in Piedmont, Mineral County, West Virginia, United States. His father was a music teacher ...

. Duke Ellington's orchestra went to Roseland to catch Armstrong's performances.

During this time, Armstrong recorded with Clarence Williams (a friend from New Orleans), the Williams Blue Five, Sidney Bechet

Sidney Bechet (May 14, 1897 – May 14, 1959) was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer. He was one of the first important soloists in jazz, and first recorded several months before trumpeter Louis Armstrong. His erratic tempe ...

, and blues singers Alberta Hunter, Ma Rainey

Gertrude "Ma" Rainey ( Pridgett; April 26, 1886 – December 22, 1939) was an American blues singer and influential early blues recording artist. Dubbed the "Mother of the Blues", she bridged earlier vaudeville and the authentic expression of s ...

, and Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1894 – September 26, 1937) was an American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the " Empress of the Blues", she was the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. Inducted into the Rock a ...

.

The Hot Five

In 1925, Armstrong returned to Chicago largely at the insistence of Lil, who wanted to expand his career and his income. In publicity, much to his chagrin, she billed him as "The World's Greatest Trumpet Player". For a time he was a member of the Lil Hardin Armstrong Band and working for his wife. He formedLouis Armstrong and his Hot Five Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ...

and recorded the hits "Potato Head Blues

"Potato Head Blues" is a Louis Armstrong composition regarded as one of his finest recordings. It was made by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven for Okeh Records in Chicago, Illinois on May 10, 1927. It was recorded during a remarkably productiv ...

" and "Muggles

In J. K. Rowling's '' Harry Potter'' series, a Muggle () is a person who lacks any sort of magical ability and was not born in a magical family. Muggles can also be described as people who do not have any magical blood inside them. It differs f ...

". The word "muggles" was a slang term for marijuana, something he used often during his life.

The Hot Five included

The Hot Five included Kid Ory

Edward "Kid" Ory (December 25, 1886 – January 23, 1973) was an American jazz composer, trombonist and bandleader. One of the early users of the glissando technique, he helped establish it as a central element of New Orleans jazz.

He was ...

(trombone), Johnny Dodds (clarinet), Johnny St. Cyr

Johnny St. Cyr (April 17, 1890 – June 17, 1966) was an American jazz banjoist and guitarist. For banjo his by far most used type in records at least was the six string one. On a famous “action photo” with Jelly Roll Morton’s Red Hot Pepp ...

(banjo), Lil Armstrong on piano, and usually no drummer. Over a twelve-month period starting in November 1925, this quintet produced twenty-four records. Armstrong's band leading style was easygoing, as St. Cyr noted, "One felt so relaxed working with him, and he was very broad-minded ... always did his best to feature each individual." Among the Hot Five and Seven records were "Cornet Chop Suey", "Struttin' With Some Barbecue", "Hotter Than that" and "Potato Head Blues", all featuring highly creative solos by Armstrong. According to Thomas Brothers, recordings, such as "Struttin' with Some Barbeque", were so superb, "planned with density and variety, bluesyness, and showiness," that the arrangements were probably showcased at the Sunset Café. His recordings soon after with pianist Earl "Fatha" Hines

Earl Kenneth Hines, also known as Earl "Fatha" Hines (December 28, 1903 – April 22, 1983), was an American jazz pianist and bandleader. He was one of the most influential figures in the development of jazz piano and, according to one source, " ...

, their famous 1928 " Weather Bird" duet and Armstrong's trumpet introduction to and solo in "West End Blues

"West End Blues" is a multi-strain twelve-bar blues composition by Joe "King" Oliver. It is most commonly performed as an instrumental, although it has lyrics added by Clarence Williams.

King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopators made the first rec ...

", remain some of the most influential improvisations in jazz history. Young trumpet players across the country bought these recordings and memorized his solos.

Armstrong was now free to develop his personal style as he wished, which included a heavy dose of effervescent jive, such as "Whip That Thing, Miss Lil" and "Mr. Johnny Dodds, Aw, Do That Clarinet, Boy!"

Armstrong also played with Erskine Tate

Erskine Tate (January 14, 1895, Memphis, Tennessee, – December 17, 1978, Chicago) was an American jazz violinist and bandleader.

Tate moved to Chicago in 1912 and was an early figure on the Chicago jazz scene, playing with his band, the Ven ...

's Little Symphony, which played mostly at the Vendome Theatre. They furnished music for silent movies and live shows, including jazz versions of classical music, such as "Madame Butterfly

''Madama Butterfly'' (; ''Madame Butterfly'') is an opera in three acts (originally two) by Giacomo Puccini, with an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa.

It is based on the short story " Madame Butterfly" (1898) by John Lut ...

", which gave Armstrong experience with longer forms of music and with hosting before a large audience. He began scat singing

In vocal jazz, scat singing is vocal improvisation with wordless vocables, nonsense syllables or without words at all. In scat singing, the singer improvises melodies and rhythms using the voice as an instrument rather than a speaking medium. ...

(improvised vocal jazz using nonsensical words) and was among the first to record it, on the Hot Five recording " Heebie Jeebies" in 1926. The recording was so popular that the group became the most famous jazz band in the United States, even though they had seldom performed live. Young musicians across the country, black or white, were turned on by Armstrong's new type of jazz.

After separating from Lil, Armstrong started to play at the Sunset Café for Al Capone's associate Joe Glaser Joseph G. Glaser (December 17, 1896 – June 6, 1969) was an artist manager known for his involvement in the careers of jazz musicians, including Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday.

Biography

Glaser was the son of a Chicago family of Russian Jewi ...

in the Carroll Dickerson

Carroll Dickerson (November 1, 1895 – October 9, 1957) was a Chicago and New York-based dixieland jazz violinist and bandleader, probably better known for his extensive work with Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines or his more brief work to ...

Orchestra, with Earl Hines on piano, which was renamed Louis Armstrong and his Stompers, though Hines was the music director and Glaser managed the orchestra. Hines and Armstrong became fast friends and successful collaborators. It was at the Sunset Café that Armstrong accompanied singer Adelaide Hall. It was during Hall's tenure at the venue that she experimented, developed and expanded her scat singing with Armstrong's guidance and encouragement.

In the first half of 1927, Armstrong assembled his Hot Seven group, which added drummer Al "Baby" Dodds and tuba player, Pete Briggs, while preserving most of his original Hot Five lineup. John Thomas replaced Kid Ory on trombone. Later that year he organized a series of new Hot Five sessions which resulted in nine more records. In the last half of 1928, he started recording with a new group: Zutty Singleton

Arthur James "Zutty" Singleton (May 14, 1898 – July 14, 1975) was an American jazz drummer.

Career

Singleton was born in Bunkie, Louisiana, United States, and raised in New Orleans. According to his ''Jazz Profiles'' biography, his unusual ...

(drums), Earl Hines (piano), Jimmy Strong (clarinet), Fred Robinson (trombone), and Mancy Carr (banjo).

The Harlem Renaissance

Armstrong made a huge impact during the 1920s Harlem Renaissance. His music touched well-known writer Langston Hughes. Hughes admired Armstrong and acknowledged him as one of the most recognized musicians of the era. Hughes wrote many books that celebrated jazz and recognized Armstrong as one of the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance's newfound love of African-American culture. The sound of jazz, along with musicians such as Armstrong, helped shape Hughes as a writer. Just like the musicians, Hughes wrote his words with jazz. Armstrong changed jazz during the Harlem Renaissance. As "The World's Greatest Trumpet Player" during this time, Armstrong cemented his legacy and continued a focus on his vocal career. His popularity brought together many black and white audiences.Emerging as a vocalist

Armstrong returned to New York in 1929, where he played in the pit orchestra for the musical ''Hot Chocolates'', an all-black revue written by Andy Razaf and pianist Fats Waller. He made a cameo appearance as a vocalist, regularly stealing the show with his rendition of " Ain't Misbehavin'". His version of the song became his biggest selling record yet. Armstrong started to work atConnie's Inn Connie's Inn was a Harlem, New York City, nightclub established in 1923 by Connie Immerman ''(né'' Conrad Immerman; 1893–1967) in partnership with two of his brothers, George (1884–1944) and Louie Immerman (1882–1955). Having immigrated from ...

in Harlem, chief rival to the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

, a venue for elaborately staged floor shows, and a front for gangster Dutch Schultz

Dutch Schultz (born Arthur Simon Flegenheimer; August 6, 1901October 24, 1935) was an American mobster. Based in New York City in the 1920s and 1930s, he made his fortune in organized crime-related activities, including bootlegging and the n ...

. Armstrong had considerable success with vocal recordings, including versions of songs composed by his old friend Hoagy Carmichael

Hoagland Howard Carmichael (November 22, 1899 – December 27, 1981) was an American musician, composer, songwriter, actor and lawyer. Carmichael was one of the most successful Tin Pan Alley songwriters of the 1930s, and was among the first ...

. His 1930s recordings took full advantage of the RCA ribbon microphone

A ribbon microphone, also known as a ribbon velocity microphone, is a type of microphone that uses a thin aluminum, duraluminum or nanofilm of electrically conductive ribbon placed between the poles of a magnet to produce a voltage by electromag ...

, introduced in 1931, which imparted warmth to vocals and became an intrinsic part of the 'crooning

Crooner is a term used to describe primarily male singers who performed using a smooth style made possible by better microphones which picked up quieter sounds and a wider range of frequencies, allowing the singer to access a more dynamic range ...

' sound of artists like Bing Crosby. Armstrong's interpretation of Carmichael's " Stardust" became one of the most successful versions of this song ever recorded, showcasing Armstrong's unique vocal sound and style and his innovative approach to singing songs that were already standards.

Armstrong's radical re-working of Sidney Arodin and Carmichael's " Lazy River" (recorded in 1931) encapsulated his groundbreaking approach to melody and phrasing. The song begins with a brief trumpet solo, then the main melody is introduced by sobbing horns, memorably punctuated by Armstrong's growling interjections at the end of each bar: "Yeah! ..."Uh-huh"..."Sure"..."Way down, way down." In the first verse, he ignores the notated melody and sings as if playing a trumpet solo, pitching most of the first line on a single note and using strongly syncopated phrasing. In the second stanza he breaks into an almost fully improvised melody, which then evolves into a classic passage of Armstrong "scat singing".

As with his trumpet playing, Armstrong's vocal innovations served as a foundation for jazz vocal interpretation. The uniquely gravelly coloration of his voice became an archetype that was endlessly imitated. His scat singing was enriched by his matchless experience as a trumpet soloist. His resonant, velvety lower-register tone and bubbling cadences on sides such as "Lazy River" exerted a huge influence on younger white singers such as Bing Crosby.

Work during hard times

The Great Depression of the early 1930s was especially hard on the jazz scene. The Cotton Club closed in 1936 after a long downward spiral and many musicians stopped playing altogether as club dates evaporated. Bix Beiderbecke died and Fletcher Henderson's band broke up. King Oliver made a few records but otherwise struggled.

The Great Depression of the early 1930s was especially hard on the jazz scene. The Cotton Club closed in 1936 after a long downward spiral and many musicians stopped playing altogether as club dates evaporated. Bix Beiderbecke died and Fletcher Henderson's band broke up. King Oliver made a few records but otherwise struggled. Sidney Bechet

Sidney Bechet (May 14, 1897 – May 14, 1959) was an American jazz saxophonist, clarinetist, and composer. He was one of the first important soloists in jazz, and first recorded several months before trumpeter Louis Armstrong. His erratic tempe ...

became a tailor, later moving to Paris and Kid Ory returned to New Orleans and raised chickens.

Armstrong moved to Los Angeles in 1930 to seek new opportunities. He played at the New Cotton Club in Los Angeles with Lionel Hampton on drums. The band drew the Hollywood crowd, which could still afford a lavish night life, while radio broadcasts from the club connected with younger audiences at home. Bing Crosby and many other celebrities were regulars at the club. In 1931, Armstrong appeared in his first movie, ''Ex-Flame'', and was also convicted of marijuana possession but received a suspended sentence. He returned to Chicago in late 1931 and played in bands more in the Guy Lombardo

Gaetano Alberto "Guy" Lombardo (June 19, 1902 – November 5, 1977) was an Italian-Canadian-American bandleader, violinist, and hydroplane racer.

Lombardo formed the Royal Canadians in 1924 with his brothers Carmen, Lebert and Victor, and oth ...

vein and he recorded more standards. When the mob insisted that he get out of town, Armstrong visited New Orleans, had a hero's welcome, and saw old friends. He sponsored a local baseball team known as Armstrong's Secret Nine and had a cigar named after him. But soon he was on the road again. After a tour across the country shadowed by the mob, he fled to Europe.

After returning to the United States, he undertook several exhausting tours. His agent Johnny Collins's erratic behavior and his own spending ways left Armstrong short of cash. Breach of contract violations plagued him. He hired Joe Glaser Joseph G. Glaser (December 17, 1896 – June 6, 1969) was an artist manager known for his involvement in the careers of jazz musicians, including Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday.

Biography

Glaser was the son of a Chicago family of Russian Jewi ...

as his new manager, a tough mob-connected wheeler-dealer, who began to straighten out his legal mess, mob troubles and debts. Armstrong also began to experience problems with his fingers and lips, aggravated by his unorthodox playing style. As a result, he branched out, developing his vocal style and making his first theatrical appearances. He appeared in movies again, including Crosby's 1936 hit '' Pennies from Heaven''. In 1937, Armstrong substituted for Rudy Vallee

Rudy or Rudi is a masculine given name, sometimes short for Rudolf, Rudolph, Rawad, Rudra, Ruairidh, or variations thereof, a nickname and a surname which may refer to:

People Given name or nickname

*Rudolf Rudy Andeweg (born 1952), Dutch poli ...

on the CBS radio network and became the first African American to host a sponsored, national broadcast.

Reviving his career with the All Stars

After spending many years on the road, Armstrong settled permanently in Queens, New York in 1943, in contentment with his fourth wife, Lucille. Although subject to the vicissitudes of

After spending many years on the road, Armstrong settled permanently in Queens, New York in 1943, in contentment with his fourth wife, Lucille. Although subject to the vicissitudes of Tin Pan Alley

Tin Pan Alley was a collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated the popular music of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It originally referred to a specific place: West 28th Street ...

and the gangster-ridden music business, as well as anti-black prejudice, he continued to develop his playing.

Bookings for big bands tapered off during the 1940s due to changes in public tastes. Ballrooms closed and there was competition from other types of music, especially pop vocals, becoming more popular than big band music. It became impossible under such circumstances to finance a 16-piece touring band.

A widespread revival of interest in the 1940s in the traditional jazz of the 1920s made it possible for Armstrong to consider a return to the small-group musical style of his youth. Armstrong was featured as a guest artist with Lionel Hampton's band at the famed second Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is a Major League Baseball (MLB) stadium on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is the home of the Chicago Cubs, one of the city's two MLB franchises. It first opened in 1914 as Weeghman Park for Charles Weeghman's Chicago ...

in Los Angeles, produced by Leon Hefflin Sr.

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again fro ...

, on October 12, 1946. He also led a highly successful small-group jazz concert at New York Town Hall on May 17, 1947, featuring Armstrong with trombonist/singer Jack Teagarden

Weldon Leo "Jack" Teagarden (August 20, 1905 – January 15, 1964) was an American jazz trombonist and singer. According to critic Scott Yannow of Allmusic, Teagarden was the preeminent American jazz trombone player before the bebop era of the 19 ...

. During the concert, Armstrong and Teagarden performed a duet on Hoagy Carmichael's " Rockin' Chair" they then recorded for Okeh Records.

Armstrong's manager, Joe Glaser, changed the Armstrong big band on August 13, 1947 into a six-piece traditional jazz group featuring Armstrong with (initially) Teagarden, Earl Hines and other top swing and Dixieland musicians, most of whom were previously leaders of big bands. The new group was announced at the opening of Billy Berg's Supper Club.

This smaller group was called Louis Armstrong and His All Stars and included at various times Earl "Fatha" Hines, Barney Bigard, Edmond Hall

Edmond Hall (May 15, 1901 – February 11, 1967) was an American jazz clarinetist and bandleader. Over his career, Hall worked extensively with many leading performers as both a sideman and bandleader and is possibly best known for the 1941 ch ...

, Jack Teagarden, Trummy Young

James "Trummy" Young (January 12, 1912 – September 10, 1984) was an American trombonist in the swing era. He established himself as a star during his 12 years performing with Louis Armstrong in Armstrong's All Stars. He had one hit with his v ...

, Arvell Shaw

Arvell Shaw (September 15, 1923 – December 5, 2002) was an American jazz double-bassist, best known for his work with Louis Armstrong.

Life and career

He was born on September 15, 1923 in St. Louis, Missouri. Shaw learned to play tuba in high ...

, Billy Kyle

William Osborne Kyle (July 14, 1914 – February 23, 1966) was an American jazz pianist. He is perhaps best known as an accompanist.

Biography

Kyle was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. He began playing the piano in school and ...

, Marty Napoleon

Marty Napoleon (June 2, 1921 – April 27, 2015) was an American jazz pianist. He replaced Earl Hines in Louis Armstrong's All Stars band in 1952. In 1946 he worked with Gene Krupa and went on to work with his uncle Phil Napoleon, a trumpeter, ...

, Big Sid "Buddy" Catlett, Cozy Cole

William Randolph "Cozy" Cole (October 17, 1909 – January 9, 1981) was an American jazz drummer who worked with Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong among others and led his own groups.

Life and career

William Randolph Cole was born in East Or ...

, Tyree Glenn

Tyree Glenn, born William Tyree Glenn (November 23, 1912, Corsicana, Texas, United States, – May 18, 1974, Englewood, New Jersey), was an American trombone and vibraphone player.

Biography

Tyree played trombone and vibraphone with local Texas ...

, Barrett Deems

Barrett Deems (March 1, 1914 – September 15, 1998) was an American swing drummer from Springfield, Illinois, United States. He worked in bands led by Jimmy Dorsey, Louis Armstrong, Red Norvo, and Muggsy Spanier.

In ''High Society'', a 195 ...

, Mort Herbert, Joe Darensbourg

Joe Darensbourg (July 9, 1906 – May 24, 1985) was an American, New Orleans-based jazz clarinetist and saxophonist, notable for his work with Buddy Petit, Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Creath, Fate Marable, Andy Kirk, Kid Ory, Wingy Manone

...

, Eddie Shu

Eddie Shu ''(ne'' Edward Shulman; 18 March 1918 New York City — 4 July 1986) was an American jazz musician who played saxophone, clarinet, trumpet, harmonica, and accordion. He was also a comedic ventriloquist.

Career

Shu learned violin and ...

, Joe Muranyi

Joseph P. Muranyi (January 14, 1928 – April 20, 2012) was an American jazz clarinetist, producer and critic.

Muranyi studied with Lennie Tristano but was primarily interested in early jazz styles such as Dixieland and swing. After playing ...

and percussionist Danny Barcelona.

On February 28, 1948, Suzy Delair sang the French song "C'est si bon

"" (; ) is a French popular song composed in 1947 by Henri Betti with the lyrics by André Hornez. The English lyrics were written in 1949 by Jerry Seelen. The song has been adapted in several languages.

History

In July 1947, Henri Bet ...

" at the Hotel Negresco

The Hotel Negresco is a hotel and site of the restaurant ''Le Chantecler'', located on the Promenade des Anglais on the Baie des Anges in Nice, France. It was named after Henri Negresco (1868–1920), who had the palatial hotel constructed in 191 ...

during the first Nice Jazz Festival

The Nice Jazz Festival (, ), held annually since 1948 in Nice, on the French Riviera, is "the first jazz festival of international significance." At the inaugural festival, Louis Armstrong and his All Stars were the headliners. Frommer's calls i ...

. Louis Armstrong was present and loved the song. On June 26, 1950, he recorded the American version of the song (English lyrics by Jerry Seelen

Jerome Lincoln Seelen (March 11, 1912 - September 12, 1981) was an American screenwriter and lyricist .

Biography

Jerry Seelen wrote lyrics for songs in musical films and wrote screenplays for radio and television.

During his lyricist career, ...

) in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

with Sy Oliver

Melvin James "Sy" Oliver (December 17, 1910 – May 28, 1988) was an American jazz arranger, trumpeter, composer, singer and bandleader.

Life

Sy Oliver was born in Battle Creek, Michigan, United States. His mother was a piano teacher, and his ...

and his Orchestra. When it was released, the disc was a worldwide success and the song was then performed by the greatest international singers.

He was the first jazz musician to appear on the cover of ''Time'' magazine, on February 21, 1949. Louis Armstrong and his All Stars were featured at the ninth Cavalcade of Jazz concert also at Wrigley Field

Wrigley Field is a Major League Baseball (MLB) stadium on the North Side of Chicago, Illinois. It is the home of the Chicago Cubs, one of the city's two MLB franchises. It first opened in 1914 as Weeghman Park for Charles Weeghman's Chicago ...

in Los Angeles produced by Leon Hefflin Sr.

Leon, Léon (French) or León (Spanish) may refer to:

Places

Europe

* León, Spain, capital city of the Province of León

* Province of León, Spain

* Kingdom of León, an independent state in the Iberian Peninsula from 910 to 1230 and again fro ...

held on June 7, 1953, along with Shorty Rogers

Milton "Shorty" Rogers (born Milton Rajonsky; April 14, 1924 – November 7, 1994) was an American jazz musician, one of the principal creators of West Coast jazz. He played trumpet and flugelhorn and was in demand for his skills as an arrang ...

, Roy Brown, Don Tosti and His Mexican Jazzmen, Earl Bostic

Eugene Earl Bostic (April 25, 1913 – October 28, 1965) was an American alto saxophonist. Bostic's recording career was diverse, his musical output encompassing jazz, swing, jump blues and the post-war American rhythm and blues style, which he ...

, and Nat "King" Cole.

Over 30 years, Armstrong played more than 300 performances a year, making many recordings and appearing in over thirty films.

A jazz ambassador

By the 1950s, Armstrong was a widely beloved American icon and cultural ambassador who commanded an international fanbase. However, a growing generation gap became apparent between him and the young jazz musicians who emerged in the postwar era such as

By the 1950s, Armstrong was a widely beloved American icon and cultural ambassador who commanded an international fanbase. However, a growing generation gap became apparent between him and the young jazz musicians who emerged in the postwar era such as Charlie Parker

Charles Parker Jr. (August 29, 1920 – March 12, 1955), nicknamed "Bird" or "Yardbird", was an American jazz saxophonist, band leader and composer. Parker was a highly influential soloist and leading figure in the development of bebop, a form ...

, Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926September 28, 1991) was an American trumpeter, bandleader, and composer. He is among the most influential and acclaimed figures in the history of jazz and 20th-century music. Davis adopted a variety of musi ...

, and Sonny Rollins. The postwar generation regarded their music as abstract art and considered Armstrong's vaudevillian style, half-musician and half-stage entertainer, outmoded and Uncle Tomism. "... he seemed a link to minstrelsy that we were ashamed of." He called bebop "Chinese music". While touring Australia in 1954, he was asked if he could play bebop. "'Bebop?' he husked. 'I just play music. Guys who invent terms like that are walking the streets with their instruments under their arms'".

In the 1960s, he toured

In the 1960s, he toured Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

and Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

.

After finishing his contract with Decca Records, he went freelance and recorded for other labels. He continued an intense international touring schedule, but in 1959 he suffered a heart attack in Italy and had to rest.

In 1964, after over two years without setting foot in a studio, he recorded his biggest-selling record, " Hello, Dolly!", a song by Jerry Herman

Gerald Sheldon Herman (July 10, 1931December 26, 2019) was an American composer and lyricist, known for his work in Broadway theatre.

One of the most commercially successful Broadway songwriters of his time, Herman was the composer and lyricist ...

, originally sung by Carol Channing

Carol Elaine Channing (January 31, 1921 – January 15, 2019) was an American actress, singer, dancer and comedian who starred in Broadway and film musicals. Her characters usually had a fervent expressiveness and an easily identifiable voice, ...

. Armstrong's version remained on the Hot 100 for 22 weeks, longer than any other record produced that year, and went to No. 1 making him, at 62 years, 9 months and 5 days, the oldest person to accomplish that feat. His hit dislodged The Beatles

The Beatles were an English rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the most influential band of all time and were integral to the developmen ...

from the No. 1 position they had occupied for 14 consecutive weeks with three different songs.

Armstrong toured well into his 60s, even visiting part of the Communist Bloc in 1965. He also toured Africa, Europe, and Asia under the sponsorship of the US State Department with great success, earning the nickname "Ambassador Satch" and inspiring Dave Brubeck to compose his jazz musical '' The Real Ambassadors''. By 1968, he was approaching 70 and his health was failing. His heart and kidney ailments forced him to stop touring. He did not perform publicly in 1969 and spent most of the year recuperating at home. Meanwhile, his longtime manager Joe Glaser died. By the summer of 1970, his doctors pronounced him fit enough to resume live performances. He embarked on another world tour, but a heart attack forced him to take a break for two months.

Armstrong made his last recorded trumpet performances on his 1968 album '' Disney Songs the Satchmo Way''.

Personal life

Pronunciation of name

The Louis Armstrong House Museum website states: In a memoir written forRobert Goffin

Robert Goffin (21 May 1898 – 27 June 1984) was a Belgian lawyer, author, and poet, credited with writing the first "serious" book on jazz, ''Aux Frontières du Jazz'' in 1932.Epperson.

Life

Robert Goffin was born in Ohain, Brabant Province i ...

between 1943 and 1944, Armstrong stated, "All white folks call me Louie," suggesting that he himself did not, or that no whites addressed him by one of his nicknames such as Pops. That said, Armstrong was registered as "Lewie" for the 1920 U.S. Census. On various live records he is called "Louie" on stage, such as on the 1952 "Can Anyone Explain?" from the live album ''In Scandinavia vol.1''. The same applies to his 1952 studio recording of the song "Chloe", where the choir in the background sings "Louie ... Louie", with Armstrong responding "What was that? Somebody called my name?". "Lewie" is the French pronunciation of "Louis" and is commonly used in Louisiana.

Family

Armstrong was performing at the Brick House in

Armstrong was performing at the Brick House in Gretna, Louisiana

Gretna is the second-largest city in, and parish seat of, Jefferson Parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

"Gretna, Louisiana (LA) Detailed Profile" (notes),

''City Data'', 2007, webpage:

C-Gretna

"Census 2000 Data for the State of Lou ...

, when he met Daisy Parker, a local prostitute, and started an affair as a client. He returned to Gretna on several occasions to visit her. He found the courage to look for her home to see her away from work. There he found out she had a common-law husband. Not long after that fiasco, Parker traveled to Armstrong's home on Perdido Street.Bergreen (1997), 134–137. They checked into Kid Green's hotel that evening. On the next day, March 19, 1919, Armstrong and Parker married at City Hall. They adopted a three-year-old boy, Clarence, whose mother, Armstrong's cousin Flora, had died soon after giving birth. Clarence Armstrong was mentally disabled as a result of a head injury at an early age, and Armstrong spent the rest of his life taking care of him. His marriage to Parker ended when they separated in 1923.

On February 4, 1924, he married Lil Hardin Armstrong

Lillian Hardin Armstrong (née Hardin; February 3, 1898 – August 27, 1971) was an American jazz pianist, composer, arranger, singer, and bandleader. She was the second wife of Louis Armstrong, with whom she collaborated on many recordings in ...

, King Oliver's pianist. She had divorced her first husband a few years earlier. His second wife helped him develop his career, but they separated in 1931 and divorced in 1938. Armstrong then married Alpha Smith. His relationship with Alpha began while he was playing at the Vendome during the 1920s and continued long after. His marriage to her lasted four years; they divorced in 1942. Louis then married Lucille Wilson, a singer at the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a New York City nightclub from 1923 to 1940. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue (1923–1936), then briefly in the midtown Theater District (1936–1940).Elizabeth Winter"Cotton Club of Harlem (1923- )" Blac ...

in New York, in October 1942. They remained married until his death in 1971.

Armstrong's marriages produced no offspring. However, in December 2012, 57-year-old Sharon Preston-Folta claimed to be his daughter from a 1950s affair between Armstrong and Lucille "Sweets" Preston, a dancer at the Cotton Club. In a 1955 letter to his manager, Joe Glaser, Armstrong affirmed his belief that Preston's newborn baby was his daughter, and ordered Glaser to pay a monthly allowance of $400 ($ in dollars) to mother and child.

Personality

Armstrong was colorful and charismatic. His autobiography vexed some biographers and historians because he had a habit of telling tales, particularly about his early childhood when he was less scrutinized, and his embellishments lack consistency.Bergreen (1997), pp. 7–11.

In addition to being an entertainer, Armstrong was a leading personality. He was beloved by an American public that usually offered little access beyond their public celebrity to even the greatest

Armstrong was colorful and charismatic. His autobiography vexed some biographers and historians because he had a habit of telling tales, particularly about his early childhood when he was less scrutinized, and his embellishments lack consistency.Bergreen (1997), pp. 7–11.

In addition to being an entertainer, Armstrong was a leading personality. He was beloved by an American public that usually offered little access beyond their public celebrity to even the greatest African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

performers, and he was able to live a private life of access and privilege afforded to few other African Americans during that era.

He generally remained politically neutral, which at times alienated him from members of the black community who expected him to use his prominence within white America to become more outspoken during the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

. However, he did criticize President Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

for not acting forcefully enough on civil rights.

Health problems

The trumpet is notoriously hard on thelips

The lips are the visible body part at the mouth of many animals, including humans. Lips are soft, movable, and serve as the opening for food intake and in the articulation of sound and speech. Human lips are a tactile sensory organ, and can be ...

, and Armstrong suffered from lip damage over most of his life. This was due to his aggressive style of playing and preference for narrow mouthpieces that would stay in place more easily, but which tended to dig into the soft flesh of his inner lip. During his 1930s European tour, he suffered an ulceration so severe that he had to stop playing entirely for a year. Eventually he took to using salves and creams on his lips and also cutting off scar tissue with a razor blade. By the 1950s, he was an official spokesman for Ansatz-Creme Lip Salve.

During a backstage meeting with trombonist Marshall Brown in 1959, Armstrong received the suggestion to see a doctor and receive proper treatment for his lips instead of relying on home remedies, but he did not get around to that until his final years, by which point his health was failing and the doctors considered surgery too risky.

Also in 1959, Armstrong was hospitalized for pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

while on tour in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Doctors were concerned about his lungs and heart, but by June 26 he rallied.

Nicknames

The nicknames "Satchmo" and "Satch" are short for "Satchelmouth". The nickname origin is uncertain. The most common tale that biographers tell is the story of Armstrong as a young boy in New Orleans dancing for pennies. He scooped the coins off the street and stuck them into his mouth to prevent bigger children from stealing them. Someone dubbed him "satchel mouth" for his mouth acting as a satchel. Another tale is that because of his large mouth, he was nicknamed "satchel mouth" which was shortened to "Satchmo".

Early on he was also known as "Dipper", short for "Dippermouth", a reference to the piece ''Dippermouth Blues'' and something of a riff on his unusual

The nicknames "Satchmo" and "Satch" are short for "Satchelmouth". The nickname origin is uncertain. The most common tale that biographers tell is the story of Armstrong as a young boy in New Orleans dancing for pennies. He scooped the coins off the street and stuck them into his mouth to prevent bigger children from stealing them. Someone dubbed him "satchel mouth" for his mouth acting as a satchel. Another tale is that because of his large mouth, he was nicknamed "satchel mouth" which was shortened to "Satchmo".

Early on he was also known as "Dipper", short for "Dippermouth", a reference to the piece ''Dippermouth Blues'' and something of a riff on his unusual embouchure

Embouchure () or lipping is the use of the lips, facial muscles, tongue, and teeth in playing a wind instrument. This includes shaping the lips to the mouthpiece of a woodwind instrument or the mouthpiece of a brass instrument. The word is o ...

.

The nickname "Pops" came from Armstrong's own tendency to forget people's names and simply call them "Pops" instead. The nickname was turned on Armstrong himself. It was used as the title of a 2010 biography of Armstrong by Terry Teachout.

After a competition at the Savoy, he was crowned and nicknamed "King Menelik", after the Emperor of Ethiopia, for slaying " ofay jazz demons".

Race

Armstrong celebrated his heritage as anAfrican American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

man from a poor New Orleans neighborhood and tried to avoid what he called "putting on airs". Many younger black musicians criticized Armstrong for playing in front of segregated audiences and for not taking a stronger stand in the American civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the United ...

. When he did speak out, it made national news, including his criticism of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, calling him "two-faced" and "gutless" because of his inaction during the conflict

Conflict may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Conflict'' (1921 film), an American silent film directed by Stuart Paton

* ''Conflict'' (1936 film), an American boxing film starring John Wayne

* ''Conflict'' (1937 film) ...

over school desegregation

Desegregation is the process of ending the separation of two groups, usually referring to races. Desegregation is typically measured by the index of dissimilarity, allowing researchers to determine whether desegregation efforts are having impact o ...

in Little Rock, Arkansas

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

in 1957. As a protest, Armstrong cancelled a planned tour of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

on behalf of the State Department saying, "The way they're treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell"; he could not represent his government abroad when it was in conflict with its own people.

The FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

kept a file on Armstrong for his outspokenness about integration.

Religion

When asked about his religion, Armstrong answered that he was raised aBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

, always wore a Star of David, and was friends with the pope. He wore the Star of David in honor of the Karnoffsky family who took him in as a child and lent him money to buy his first cornet. He was baptized a Catholic in the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in New Orleans, and he met Pope Pius XII and Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

.

Personal habits

Armstrong was concerned with his health. He usedlaxatives

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Laxatives vary as to how they work and the side effects they may have. Certain stimulant, lub ...

to control his weight, a practice he advocated both to acquaintances and in the diet plans he published under the title ''Lose Weight the Satchmo Way''. Armstrong's laxative of preference in his younger days was Pluto Water, but when he discovered the herbal remedy Swiss Kriss, he became an enthusiastic convert, extolling its virtues to anyone who would listen and passing out packets to everyone he encountered, including members of the British Royal Family. Armstrong also appeared in humorous, risqué, cards that he had printed to send to friends. The cards bore a picture of him sitting on a toilet—as viewed through a keyhole—with the slogan ''"Satch says, 'Leave it all behind ya!'"'' The cards have sometimes been incorrectly described as ads for Swiss Kriss. In a live recording of "Baby, It's Cold Outside

"Baby, It's Cold Outside" is a popular song written by Frank Loesser in 1944 and popularized in the 1949 film '' Neptune's Daughter''. While the lyrics make no mention of a holiday, it is commonly regarded as a Christmas song owing to its winter ...

" with Velma Middleton

Velma Middleton (September 1, 1917 – February 10, 1961) was an American jazz vocalist and entertainer who sang with Louis Armstrong's big bands and small groups from 1942 until her death.

Biography

Middleton was born in Holdenville, Okl ...

, he changes the lyric from "Put another record on while I pour" to "Take some Swiss Kriss while I pour". His laxative use began as a child when his mother would collect dandelion

''Taraxacum'' () is a large genus of flowering plants in the family Asteraceae, which consists of species commonly known as dandelions. The scientific and hobby study of the genus is known as taraxacology. The genus is native to Eurasia and Nor ...

s and peppergrass around the railroad tracks to give to her children for their health.

Armstrong was a heavy marijuana smoker for much of his life and spent nine days in jail in 1930 after being arrested outside a club for drug possession. He described marijuana as "a thousand times better than whiskey".

The concern with his health and weight was balanced by his love of food, reflected in such songs as "Cheesecake", "Cornet Chop Suey", and "Struttin' with Some Barbecue", though the latter was written about a fine-looking companion, and not food. He kept a strong connection throughout his life to the cooking of New Orleans, always signing his letters, "Red beans and rice

Red beans and rice is an emblematic dish of Louisiana Creole cuisine (not originally of Cajun cuisine) traditionally made on Mondays with Kidney beans, vegetables (bell pepper, onion, and celery), spices (thyme, cayenne pepper, and bay leaf) a ...

ly yours ...".

A fan of Major League Baseball, he founded a team in New Orleans that was known as Raggedy Nine and transformed the team into his Armstrong's " Secret Nine Baseball".

Writings

Armstrong's gregariousness extended to writing. On the road, he wrote constantly, sharing favorite themes of his life with correspondents around the world. He avidly typed or wrote on whatever stationery was at hand, recording instant takes on music, sex, food, childhood memories, his heavy "medicinal" marijuana use, and even his bowel movements, which he gleefully described.Social organizations

Louis Armstrong was not, as claimed, a Freemason. Although he has been cited as a member of Montgomery Lodge No. 18 (Prince Hall) in New York, no such lodge ever existed. Armstrong did state in his autobiography that he was a member of the Knights of Pythias, which although real, is not a Masonic group. During the krewe's 1949 Mardi Gras parade, Armstrong presided as King of theZulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club

The Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club (founded 1916) is a fraternal organization in New Orleans, Louisiana which puts on the Zulu parade each year on Mardi Gras Day. Zulu is New Orleans' largest predominantly African American carnival organizati ...

, for which he was featured on the cover of ''Time'' magazine.

Music

Horn playing and early jazz