Lord Howe swamphen on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The white swamphen (''Porphyrio albus''), also known as the Lord Howe swamphen, Lord Howe gallinule or white gallinule, is an

In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from ''P. albus'' in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: ''P. raperi''. Mathews also considered ''P. albus'' distinct enough to warrant a new genus, ''Kentrophorina'', due to having a claw (or

In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from ''P. albus'' in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: ''P. raperi''. Mathews also considered ''P. albus'' distinct enough to warrant a new genus, ''Kentrophorina'', due to having a claw (or

The length of the white swamphen has been given as 36 cm (14 in) and 55 cm (22 in), making it similar to the Australasian swamphen in size. Its wings were proportionally the shortest of all swamphens. The wing of the Vienna specimen is mm long, the tail is , the culmen with its frontal shield (the fleshy plate on the head) is , the tarsus is , and the middle toe is long. The wing of the Liverpool specimen is long, the tarsus is and the middle toe is . Its tail and beak are damaged, and cannot be reliably measured. The white swamphen differed from most other swamphens (except the Australasian swamphen) in having a short middle toe; it is the same length as the tarsus, or longer, in other species. The white swamphen's tail was also the shortest. Both specimens have a claw (or spur) on their wings; it is longer and more discernible in the Vienna specimen, and sharp and buried in the feathers of the Liverpool specimen. This feature is variable among other kinds of swamphen. The softness of the

The length of the white swamphen has been given as 36 cm (14 in) and 55 cm (22 in), making it similar to the Australasian swamphen in size. Its wings were proportionally the shortest of all swamphens. The wing of the Vienna specimen is mm long, the tail is , the culmen with its frontal shield (the fleshy plate on the head) is , the tarsus is , and the middle toe is long. The wing of the Liverpool specimen is long, the tarsus is and the middle toe is . Its tail and beak are damaged, and cannot be reliably measured. The white swamphen differed from most other swamphens (except the Australasian swamphen) in having a short middle toe; it is the same length as the tarsus, or longer, in other species. The white swamphen's tail was also the shortest. Both specimens have a claw (or spur) on their wings; it is longer and more discernible in the Vienna specimen, and sharp and buried in the feathers of the Liverpool specimen. This feature is variable among other kinds of swamphen. The softness of the  Phillip gave a detailed description in 1789, possibly based on a live bird he received in Sydney:

Phillip gave a detailed description in 1789, possibly based on a live bird he received in Sydney:

BOC; Birds of Lord Howe Island by Julian Hume

– presentation of Lord Howe Island birds by

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

species of rail which lived on Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland Po ...

, east of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. It was first encountered when the crews of British ships visited the island between 1788 and 1790, and all contemporary accounts and illustrations were produced during this time. Today, two skins exist: the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of seve ...

in the Natural History Museum of Vienna, and another in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

's World Museum. Although historical confusion has existed about the provenance

Provenance (from the French ''provenir'', 'to come from/forth') is the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object. The term was originally mostly used in relation to works of art but is now used in similar senses i ...

of the specimens and the classification and anatomy of the bird, it is now thought to have been a distinct species endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to Lord Howe Island and most similar to the Australasian swamphen

The Australasian swamphen (''Porphyrio melanotus'') is a species of swamphen (''Porphyrio'') occurring in eastern Indonesia (the Moluccas, Aru and Kai Islands), Papua New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand. In New Zealand, it is known as the puk ...

. Subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

bones have also been discovered since.

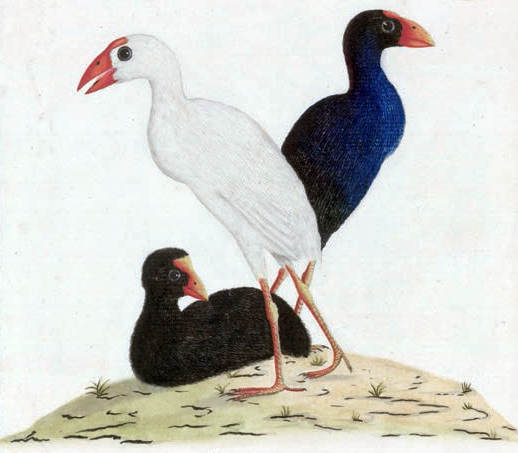

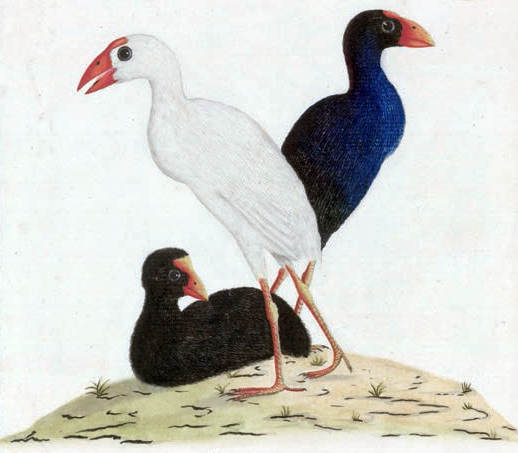

The white swamphen was long. Both known skins have mainly-white plumage, although the Liverpool specimen also has dispersed blue feathers. This is unlike other swamphens

''Porphyrio'' is the swamphen or swamp hen bird genus in the rail family. It includes some smaller species which are usually called "purple gallinules", and which are sometimes separated as genus ''Porphyrula'' or united with the gallinules pr ...

, but contemporary accounts indicate birds with all-white, all-blue, and mixed blue-and-white plumage. The chicks were black, becoming blue and then white as they aged. Although this has been interpreted as due to albinism

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

, it may have been progressive greying in which feathers lose their pigment with age. The bird's bill, frontal shield and legs were red, and it had a claw (or spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

) on its wing. Little was recorded about the white swamphen's behaviour. It may not have been flightless, but was probably a poor flier. This and its docility made the bird easy prey for visiting humans, who killed it with sticks. Reportedly once common, the species may have been hunted to extinction before 1834, when Lord Howe Island was settled.

Taxonomy

Lord Howe Island

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand, part of the Australian state of New South Wales. It lies directly east of mainland Po ...

is a small, remote island about east of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. Ships first arrived on the island in 1788, including two which supplied the British penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

on Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together wit ...

and three transport ships of the British First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command o ...

. When passed the island, the ship's commander named it after First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

Richard Howe. Crews of the visiting ships captured native birds (including white swamphens), and all contemporary descriptions and depictions of the species were made between 1788 and 1790. The bird was first mentioned by the master of HMS ''Supply'', David Blackburn, in a 1788 letter to a friend. Other accounts and illustrations were produced by Arthur Bowes Smyth, the fleet's naval officer and surgeon, who drew the first known illustration of the species; Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Greenwich Hospital School from June 1751 until ...

, governor of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

; and George Raper, midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

of . Secondhand accounts also exist, and at least ten contemporary illustrations are known. The accounts indicate that the population varied, and individual bird plumage was white, blue, or mixed blue-and-white.

In 1790, the white swamphen was scientifically described and named by the surgeon John White in a book about his time in New South Wales. He named the bird '' Fulica alba'', the specific name being derived from the Latin word for white (''albus''). White found the bird most similar to the western swamphen (''Porphyrio porphyrio'', then in the genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

''Fulica''). Although he apparently never visited Lord Howe Island, White may have questioned sailors and based some of his description on earlier accounts. He said he had described a skin at the Leverian Museum, and his book included an illustration of the specimen by the artist Sarah Stone. It is uncertain when (and how) the specimen arrived at the museum. This skin, the holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of sever ...

of the species, was purchased by the Natural History Museum of Vienna in 1806 and is catalogued as specimen NMW 50.761. The naturalist John Latham listed the bird as '' Gallinula alba'' in a later 1790 work, and wrote that it may have been a variety of purple swamphen (or " gallinule").

One other white swamphen specimen is in Liverpool's World Museum, where it is catalogued as specimen NML-VZ D3213. Obtained by the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James C ...

, it later entered the collection of the traveller William Bullock and was purchased by Lord Stanley; Stanley's son donated it to Liverpool's public museums in 1850. Although White said that the first specimen was obtained from Lord Howe Island, the provenance

Provenance (from the French ''provenir'', 'to come from/forth') is the chronology of the ownership, custody or location of a historical object. The term was originally mostly used in relation to works of art but is now used in similar senses i ...

of the second has been unclear; it was originally said to have come from New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island coun ...

, resulting in taxonomic confusion. Phillip wrote that the bird could also be found on Norfolk Island and elsewhere, but Latham said it could be found only on Norfolk Island. When the first specimen was sold by the Leverian Museum, it was listed as coming from New Holland (which Australia was called at the time)—perhaps because it was sent from Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

. A note by the naturalist Edgar Leopold Layard

Edgar Leopold Layard MBOU, (23 July 1824 – 1 January 1900) was a British diplomat and a naturalist mainly interested in ornithology and to a lesser extent the molluscs. He worked for a significant part of his life in Ceylon and late ...

on a contemporary illustration of the bird by Captain John Hunter inaccurately stated that it only lived on Ball's Pyramid

Ball's Pyramid is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera lying southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean. It is high, while measuring in length and only across, making it the tallest volcanic stack in the world. B ...

, an islet

An islet is a very small, often unnamed island. Most definitions are not precise, but some suggest that an islet has little or no vegetation and cannot support human habitation. It may be made of rock, sand and/or hard coral; may be permanen ...

off Lord Howe Island.

The Zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck

Coenraad Jacob Temminck (; 31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist and museum director.

Biography

Coenraad Jacob Temminck was born on 31 March 1778 in Amsterdam in the Dutch Republic. From his father, Jacob Temmi ...

assigned the white swamphen to the swamphen genus ''Porphyrio'' as ''P. albus'' in 1820, and the zoologist George Robert Gray

George Robert Gray FRS (8 July 1808 – 6 May 1872) was an English zoologist and author, and head of the ornithological section of the British Museum, now the Natural History Museum, in London for forty-one years. He was the younger brother ...

considered it an albino

Albinism is the congenital absence of melanin in an animal or plant resulting in white hair, feathers, scales and skin and pink or blue eyes. Individuals with the condition are referred to as albino.

Varied use and interpretation of the term ...

variety of the Australasian swamphen

The Australasian swamphen (''Porphyrio melanotus'') is a species of swamphen (''Porphyrio'') occurring in eastern Indonesia (the Moluccas, Aru and Kai Islands), Papua New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand. In New Zealand, it is known as the puk ...

(''P. melanotus'') as ''P. m. varius alba'' in 1844. The belief that the bird was simply an albino was held by several later writers, and many failed to notice that White cited Lord Howe Island as the origin of the Vienna specimen. In 1860 and 1873, the ornithologist August von Pelzeln said that the Vienna specimen had come from Norfolk Island, and assigned the species to the genus ''Notornis'' as ''N. alba''; the takahē (''P. hochstetteri'') of New Zealand was also placed in that genus at the time. In 1873, the naturalist Osbert Salvin agreed that the Lord Howe Island bird was similar to the takahē, although he had apparently never seen the Vienna specimen, basing his conclusion on a drawing provided by von Pelzeln. Salvin included a takahē-like illustration of the Vienna specimen by the artist John Gerrard Keulemans, based on von Pelzeln's drawing, in his article.

In 1875, the ornithologist George Dawson Rowley George Dawson Rowley (3 May 1822 – 21 November 1878) was an English amateur ornithologist who published a series called Ornithological Miscellany in which he reprinted notes on bird studies of the time. He studied at Eton and Trinity college and w ...

noted differences between the Vienna and Liverpool specimens and named a new species based on the latter: ''P. stanleyi'', named after Lord Stanley. He believed that the Liverpool specimen was a juvenile from Lord Howe Island or New Zealand, and continued to believe that the Vienna specimen was from Norfolk Island. Despite naming the new species, Rowley considered the possibility that ''P. stanleyi'' was an albino Australasian swamphen and considered the Vienna bird more similar to the takahē. In 1901, the ornithologist Henry Ogg Forbes had the Liverpool specimen dismounted so he could examine it for damage. Forbes found it similar enough to the Vienna specimen to belong to the same species, ''N. alba''. The zoologist Walter Rothschild

Lionel Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, (8 February 1868 – 27 August 1937) was a British banker, politician, zoologist and soldier, who was a member of the Rothschild family. As a Zionist leader, he was pres ...

considered the two species distinct from each other in 1907, but placed them both in the genus ''Notornis''. Rothschild thought that the image published by Phillip in 1789 depicted ''N. stanleyi'' from Lord Howe Island, and the image published by White in 1790 showed ''N. alba'' from Norfolk Island. He disagreed that the specimens were albinos, thinking instead that they were evolving into a white species. Rothschild published an illustration of ''N. alba'' by Keulemans where it is similar to a takahē, inaccurately showing it with dark primary feathers

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

, although the Vienna specimen on which it was based is all white. In 1910, the ornithologist Tom Iredale

Tom Iredale (24 March 1880 – 12 April 1972) was an English-born ornithologist and malacologist who had a long association with Australia, where he lived for most of his life. He was an autodidact who never went to university and lacked forma ...

demonstrated that there was no proof of the white swamphen existing anywhere but on Lord Howe Island and noted that early visitors to Norfolk Island (such as Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

and Lieutenant Philip Gidley King

Captain Philip Gidley King (23 April 1758 – 3 September 1808) was a British politician who was the third Governor of New South Wales.

When the First Fleet arrived in January 1788, King was detailed to colonise Norfolk Island for defence ...

) did not mention the bird. In 1913, after examining the Vienna specimen, Iredale concluded that the bird belonged in the genus ''Porphyrio'' and did not resemble the takahē.

In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from ''P. albus'' in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: ''P. raperi''. Mathews also considered ''P. albus'' distinct enough to warrant a new genus, ''Kentrophorina'', due to having a claw (or

In 1928, the ornithologist Gregory Mathews discussed a 1790 painting by Raper which he thought differed enough from ''P. albus'' in proportions and colouration that he named a new species based on it: ''P. raperi''. Mathews also considered ''P. albus'' distinct enough to warrant a new genus, ''Kentrophorina'', due to having a claw (or spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

) on one wing. In 1936, he conceded that ''P. raperi'' was a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are al ...

of ''P. albus''. The ornithologist Keith Alfred Hindwood

Keith Alfred Hindwood (1904-1971) was a Sydney-based Australian businessman and amateur ornithologist. He joined the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union (RAOU) in 1924, served as President 1944–1946, and was elected a Fellow of the RAOU i ...

agreed that the bird was an albino ''P. melanotus'' in 1932, and pointed out that the naturalists Johann Reinhold Forster

Johann Reinhold Forster (22 October 1729 – 9 December 1798) was a German Reformed (Calvinist) pastor and naturalist of partially Scottish descent who made contributions to the early ornithology of Europe and North America. He is best known ...

and Georg Forster

Johann George Adam Forster, also known as Georg Forster (, 27 November 1754 – 10 January 1794), was a German naturalist, ethnologist, travel writer, journalist and revolutionary. At an early age, he accompanied his father, Johann Reinhold ...

(his son) did not record the bird when Cook's ship visited Norfolk Island in 1774. In 1940, Hindwood found the white swamphen so closely related to the Australasian swamphen that he considered them subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

of the same species: ''P. albus albus'' and ''P. albus melanotus'' (since ''albus'' is the older name). Hindwood suggested that the population on Lord Howe Island was white; blue Australasian swamphens occasionally arrived (stragglers from elsewhere have been found on the island) and bred with the white birds, accounting for the blue and partially-blue individuals in the old accounts. He also pointed out that Australasian swamphens are prone to white feathering. In 1941, the biologist Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, philosopher of biology, and historian of science. His ...

proposed that the white swamphen was a partially-albinistic population of Australasian swamphens. Mayr suggested that the blue swamphens remaining on Lord Howe Island were not stragglers, but had survived because they were less conspicuous than the white ones. In 1967, the ornithologist James Greenway

James Cowan Greenway (April 7, 1903 – June 10, 1989) was an American ornithologist. An eccentric, shy, and often reclusive man, his survey of extinct and vanishing birds provided the base for much subsequent work on bird conservation.

Early y ...

also considered the white swamphen a subspecies (with ''P. stanleyi'' a synonym) and considered the white individuals albinos. He suggested that the similarities between the wing feathers of the white swamphen and the takahē were due to parallel evolution in two isolated populations of reluctant fliers.

The ornithologist Sidney Dillon Ripley

Sidney Dillon Ripley II (September 20, 1913 – March 12, 2001) was an American ornithologist and wildlife conservationist. He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution for 20 years, from 1964 to 1984, leading the institution throu ...

found the white swamphen to be intermediate between the takahē and the purple swamphen in 1977, based on patterns of the leg-scutes, and reported that X-rays of bones also showed similarities with the takahē. He considered only the Vienna specimen to be a white swamphen, whereas he considered the Liverpool specimen to be an albino Australasian swamphen (listing ''P. stanleyi '' as a junior synonym of that bird) from New Zealand. In 1991, the ornithologist Ian Hutton reported subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

bones of the white swamphen. Hutton agreed that the birds described as having white-and-blue feathers were hybrids between the white swamphen and the Australasian swamphen, an idea also considered by the ornithologists Barry Taylor and Ber van Perlo in 2000. In 2000, the writer Errol Fuller

Errol Fuller (born 19 June 1947) is an English writer and artist who lives in Tunbridge Wells, Kent. He was born in Blackpool, Lancashire, grew up in South London, and was educated at Addey and Stanhope School. He is the author of a series of bo ...

said that since swamphens are widespread colonists, it would be expected that populations would evolve similarly to the takahē when they found refuges without mammals (losing flight and becoming bulkier with stouter legs, for example); this was the case with the white swamphen. Fuller suggested that they could be called "white takahēs", which had been alluded to earlier; the white birds may have been a colour morph

In biology, polymorphism is the occurrence of two or more clearly different morphs or forms, also referred to as alternative ''phenotypes'', in the population of a species. To be classified as such, morphs must occupy the same habitat at the s ...

of the population, or the blue birds may have been Australasian swamphens which associated with the white birds.

In 2015, the biologists Juan C. Garcia-R. and Steve A. Trewick analysed the DNA of the purple swamphens. They found that the white swamphen was most closely related to the Philippine swamphen

Philippine swamphen (''Porphyrio pulverulentus'' Temminck, 1826) is a species of swamphen occurring in The Philippines. It used to be considered a subspecies of the purple swamphen The purple swamphen has been split into the following species:

* ...

(''P. pulverulentus''), and the black-backed swamphen

The black-backed swamphen (''Porphyrio indicus'') is a species of swamphen occurring from southeast Asia to Sulawesi and Borneo. It used to be considered a subspecies of the purple swamphen The purple swamphen has been split into the following sp ...

(''P. indicus'') more closely related to both than to other species in its region. Garcia-R. and Trewick used DNA from the Vienna specimen, but were unable to obtain usable DNA from the Liverpool specimen. They suggested that the white swamphen may have descended from a few migrant Philippine swamphens during the late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

(about 500,000 years ago), dispersing over other islands. This indicates a complex history, since their lineages are not recorded on the islands between them; according to the biologists, such results (based on ancient DNA sources) should be treated with caution. Although many purple swamphen taxa had been considered subspecies of the species ''P. porphyrio'', they considered this a paraphyletic

In taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In ...

(unnatural) grouping since they found different species to group among the subspecies. The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

below shows the phylogenetic position of the white swamphen according to the 2015 study:

The ornithologists Hein van Grouw and Julian P. Hume concluded in 2016 that many of the old accounts had errors in the bird's provenance, that it was endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to Lord Howe Island, and suggested when the specimens were collected (between March and May 1788) and under which circumstances they arrived in England. They concluded that the white swamphen was a valid species which changed colouration with age, after reconstructing the colouration of juvenile birds before turning white (which was distinct from other swamphens). Van Grouw and Hume found the white swamphen anatomically more similar to the Australasian swamphen than the Philippine swamphen, and suggested that studies with more-complete data sets than the earlier DNA might yield different results. Due to their anatomical similarities, geographic proximity and the recolonisation of Lord Howe and Norfolk Island by Australasian swamphens, they found it likely that the white swamphen was descended from Australasian swamphens.

In 2021, Hume and colleagues reported the results of their palaeontological reconnaissance of Lord Howe Island, which included the discovery of subfossil white swamphen bones. A complete pelvis and representatives of most limb bones were found in the dunes of Blinky Beach (situated at the end of an airport runway), and the authors stated these would provide new insight into the morphology and behaviour of the species.

Description

The length of the white swamphen has been given as 36 cm (14 in) and 55 cm (22 in), making it similar to the Australasian swamphen in size. Its wings were proportionally the shortest of all swamphens. The wing of the Vienna specimen is mm long, the tail is , the culmen with its frontal shield (the fleshy plate on the head) is , the tarsus is , and the middle toe is long. The wing of the Liverpool specimen is long, the tarsus is and the middle toe is . Its tail and beak are damaged, and cannot be reliably measured. The white swamphen differed from most other swamphens (except the Australasian swamphen) in having a short middle toe; it is the same length as the tarsus, or longer, in other species. The white swamphen's tail was also the shortest. Both specimens have a claw (or spur) on their wings; it is longer and more discernible in the Vienna specimen, and sharp and buried in the feathers of the Liverpool specimen. This feature is variable among other kinds of swamphen. The softness of the

The length of the white swamphen has been given as 36 cm (14 in) and 55 cm (22 in), making it similar to the Australasian swamphen in size. Its wings were proportionally the shortest of all swamphens. The wing of the Vienna specimen is mm long, the tail is , the culmen with its frontal shield (the fleshy plate on the head) is , the tarsus is , and the middle toe is long. The wing of the Liverpool specimen is long, the tarsus is and the middle toe is . Its tail and beak are damaged, and cannot be reliably measured. The white swamphen differed from most other swamphens (except the Australasian swamphen) in having a short middle toe; it is the same length as the tarsus, or longer, in other species. The white swamphen's tail was also the shortest. Both specimens have a claw (or spur) on their wings; it is longer and more discernible in the Vienna specimen, and sharp and buried in the feathers of the Liverpool specimen. This feature is variable among other kinds of swamphen. The softness of the rectrices

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tai ...

(tail feathers) and the lengths of the secondary

Secondary may refer to: Science and nature

* Secondary emission, of particles

** Secondary electrons, electrons generated as ionization products

* The secondary winding, or the electrical or electronic circuit connected to the secondary winding i ...

and wing covert feathers relative to the primary feathers appear to have been intermediate between those of the purple swamphen and the takahē.

Although the known skins are mostly white, contemporary illustrations depict some blue individuals; others had a mixture of white and blue feathers. Their legs were red or yellow, but the latter colour may be present only on dried specimens. The bill and frontal shield were red, and the iris was red or brown. According to notes written on an illustration by an unknown artist (in the collection of the artist Thomas Watling, inaccurately dated 1792), the chicks were black and became bluish-grey and then white as they matured. The Vienna specimen is pure white, but the Liverpool specimen has yellowish reflections on its neck and breast, blackish-blue feathers speckled on the head (concentrated near the upper surface of the shield) and neck, blue feathers on the breast, and purplish-blue feathers on the shoulders, back, scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

r, and lesser covert feathers. Some of the rectrices (tail feathers) are purplish-brown, and some of the scapular feathers and those on the mid-back are sooty-brown at the base and sooty-blue further up. The central rectrices are sooty-brown and bluish. This colouration indicates that the Liverpool specimen was a younger bird than the Vienna specimen, and the latter had reached the final stage of maturity. Since the Liverpool specimen preserves some of its original colour, van Grouw, and Hume were able to reconstruct its natural colouration before becoming white. It differed from other swamphens in having blackish-blue lores, forehead, crown, nape, and hind neck; purple-blue mantle, back, and wings; a darker rump and upper-tail covert feathers; and dark greyish-blue underparts.

Phillip gave a detailed description in 1789, possibly based on a live bird he received in Sydney:

Phillip gave a detailed description in 1789, possibly based on a live bird he received in Sydney:

Condition of the specimens

The Vienna specimen is today astudy skin

Bird collections are curated repositories of scientific specimens consisting of birds and their parts. They are a research resource for ornithology, the science of birds, and for other scientific disciplines in which information about birds is us ...

with its legs outstretched (not a taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proc ...

mount), but van Grouw and Hume suggested that Stone's 1790 illustration showed its original mounted pose. It is in good condition; although the legs are faded to a pale orange-brown, they were probably reddish in the living bird. It has no yellowish or purple feathers, contradicting Rothschild's observation. Forbes suggested that the Liverpool specimen was "remade" and mounted after Stone's illustration, though its present pose is dissimilar. Keulemans's illustration of the mount shows the present pose, so Forbes was either incorrect or a new pose was based on Keulemans's image. The Liverpool specimen is in good condition, although it has lost some feathers from its head and neck. The bill is broken, and its rhamphotheca

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food, ...

(the keratinous covering of the bill) is missing; the underlying bone was painted red to simulate an undamaged bill, which has caused some confusion. The legs have also been painted red, and there is no indication of their original colouration. The reason only white specimens are known today may be collecting bias; unusually-coloured specimens are more likely to be collected than normally-coloured ones.

Behaviour and ecology

The white swamphen inhabited wooded lowland areas in wetlands. Nothing was recorded about its social and reproductive behaviour and its nest, eggs and call were never described. Presumably it did not migrate. Blackburn's 1788 account is the only one that mentions the diet of this bird: Some contemporary accounts indicated that the bird was flightless. Rowley considered the Liverpool specimen (representing the separate species ''P. stanleyi'') capable of flight, due to its longer wings; Rothschild believed that both were flightless, although he was inconsistent about whether their wings were the same length. Van Grouw and Hume found that both specimens showed evidence of an increased terrestrial lifestyle (including decreased wing length, more robust feet and short toes), and were in the process of becoming flightless. Although it may still have been capable of flight, it was behaviourally flightless, similar to other island birds, such as some parrots. Though the white swamphen was similar in size to the Australasian swamphen, it had proportionally shorter wings and therefore a higherwing load

In aerodynamics, wing loading is the total mass of an aircraft or flying animal divided by the area of its wing. The stalling speed of an aircraft in straight, level flight is partly determined by its wing loading. An aircraft or animal with a ...

– perhaps the highest of all swamphens. Upon the discovery of subfossil pelvic and limb bones in 2021, Hume and colleagues preliminarily stated that these bones were much more robust in the white swamphen than in the volant Australasian swamphen, a trait common in flightless rails.

Van Grouw and Hume pointed out that a white colour aberration in birds is rarely caused by albinism (which is less common than formerly believed), but by leucism

Leucism () is a wide variety of conditions that result in the partial loss of pigmentation in an animal—causing white, pale, or patchy coloration of the skin, hair, feathers, scales, or cuticles, but not the eyes. It is occasionally spelled ...

or progressive greying – a phenomenon van Grouw described in 2012 and 2013. These conditions produce white feathers due to the absence of cells which produce the pigment melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

. Leucism is inherited, and the white feathering is present in juveniles and does not change with age; progressive greying causes normally-coloured juveniles to lose pigment-producing cells with age, and they become white as they moult

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

. Since contemporary accounts indicate that the white swamphen turned from black to bluish-grey and then white, Van Grouw and Hume concluded that it underwent inheritable progressive greying. Progressive greying is a common cause of white feathers in many types of birds (including rails), although such specimens have sometimes been inaccurately referred to as albinos. The condition does not affect carotenoid

Carotenoids (), also called tetraterpenoids, are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, ...

pigments (red and yellow), and the bill and legs of the white swamphens retained their colouration. The large number of white individuals on Lord Howe Island may be due to its small founding population, which would have facilitated the spread of inheritable progressive greying.

Extinction

Although the white swamphen was considered common during the late 18th century, it appears to have disappeared quickly; the period from the island's discovery to the last mention of living birds is only two years (1788–90). It had probably vanished by 1834, when Lord Howe Island was first settled, or during the following decade. Whalers and sealers had used the island for supplies, and may have hunted the bird toextinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the Endling, last individual of the species, although the Functional ext ...

. Habitat destruction probably did not play a role, and animal predators (such as rats and cats) arrived later. Several contemporary accounts stress the ease with which the island's birds were hunted, and the large number which could be taken to provision ships. In 1789, White described how the white swamphen could be caught:

The fact that they could be killed with sticks may have been due to their poor flying ability, which would have made them vulnerable to human predation. With no natural enemies on the island, they were tame and curious. The physician John Foulis conducted a mid-1840s ornithological survey on the island but did not mention the bird, so it was almost cetainly extinct by that time. In 1909, the writer Arthur Francis Basset Hull

Arthur Francis Basset Hull (1862–1945) was an Australian public servant, naturalist and philatelist. He signed the Roll of Distinguished Philatelists in 1921.

Tasmania

Hull was born on 10 October 1862 in Hobart.

In 1883–1889 Hull worked ...

expressed hope that the bird still survived in unexplored mountains.

Eight types of bird have become extinct due to human interference since Lord Howe Island was discovered, including the Lord Howe pigeon (''Columba vitiensis godmanae''), the Lord Howe parakeet (''Cyanoramphus subflavescens''), the Lord Howe gerygone (''Gerygone insularis''), the Lord Howe fantail (''Rhipidura fuliginosa cervina''), the Lord Howe thrush (''Turdus poliocephalus vinitinctus''), the robust white-eye (''Zosterops strenuus'') and the Lord Howe starling (''Aplonis fusca hulliana''). The extinction of so many native birds is similar to extinctions on several other islands, such as the Mascarenes.

See also

*List of recently extinct bird species

Around 129 species of birds have become extinct since 1500, and the rate of extinction seems to be increasing. The situation is exemplified by Hawaii, where 30% of all known recently extinct bird taxa originally lived. Other areas, such as Gua ...

References

External links

BOC; Birds of Lord Howe Island by Julian Hume

– presentation of Lord Howe Island birds by

Julian Hume

Julian Pender Hume (born 3 March 1960) is an English palaeontologist, artist and writer who lives in Wickham, Hampshire. He was born in Ashford, Kent, and grew up in Portsmouth, England. He attended Crookhorn Comprehensive School between 1971 an ...

, including the white swamphen.

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1050513

white swamphen

Extinct birds of Lord Howe Island

Extinct flightless birds

Bird extinctions since 1500

white swamphen

Taxa named by John White (surgeon)