Lord George Gordon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lord George Gordon (26 December 1751 – 1 November 1793) was a British politician best known for lending his name to the

The Old Bailey and Newgate

', ch.XVIII, pp.204–219, T. Fisher Unwin, London 1902

Gordon associated only with pious Jews; in his passionate enthusiasm for his new faith, he refused to deal with any Jew who compromised the

Gordon associated only with pious Jews; in his passionate enthusiasm for his new faith, he refused to deal with any Jew who compromised the

Lord George Gordon and Cabalistic Freemasonry: Beating Jacobite Swords into Jacobin Ploughshares

by Marsha Keith Schuchard {{DEFAULTSORT:Gordon, Lord George 1751 births 1793 deaths Anglo-Scots George People excommunicated by the Church of England Converts to Judaism from Anglicanism English Jews Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1774–1780 Scottish Jews Younger sons of dukes Deaths from typhoid fever Infectious disease deaths in England Prisoners who died in England and Wales detention English people who died in prison custody British politicians convicted of crimes People acquitted of treason People educated at Eton College Persecution of Catholics

Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against Briti ...

of 1780.

An eccentric and flighty personality, he was born into the Scottish nobility and sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

from 1774 to 1780. His life ended after a number of controversies, notably one surrounding his conversion to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism ( he, גיור, ''giyur'') is the process by which non-Jews adopt the Jewish religion and become members of the Jewish ethnoreligious community. It thus resembles both conversion to other religions and naturalization. ...

, for which he was ostracised. He died in Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

.Gordon, Charles The Old Bailey and Newgate

', ch.XVIII, pp.204–219, T. Fisher Unwin, London 1902

Early life

George Gordon was born in London, England, third and youngest son ofCosmo George Gordon, 3rd Duke of Gordon

Cosmo George Gordon, 3rd Duke of Gordon KT (27 April 1720 – 5 August 1752), styled Marquess of Huntly until 1728, was a Scottish peer.

Life

Gordon was the son of the 2nd Duke of Gordon and was named after his father's close Jacobite friend ...

, and his wife, Catherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

, and the brother of Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon

Alexander Gordon, 4th Duke of Gordon, KT (18 June 1743 – 17 June 1827), styled Marquess of Huntly until 1752, was a Scottish nobleman, described by Kaimes as the "greatest subject in Britain", and was also known as the Cock o' the North, the tr ...

. In 1759 he had been bought an Ensign's commission in the army's 89th (Highland) Regiment of Foot, then commanded by his stepfather Staats Long Morris, but after completing his education at Eton, he entered the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

in 1763 at the age of 12. He received promotion to the rank of Lieutenant, but his career stagnated and he received no further promotions. His behaviour in raising the poor living conditions of his sailors led to him being mistrusted by his fellow officers, although it contributed to his popularity amongst ordinary seamen. Lord Sandwich

Earl of Sandwich is a noble title in the Peerage of England, held since its creation by the House of Montagu. It is nominally associated with Sandwich, Kent. It was created in 1660 for the prominent naval commander Admiral Sir Edward Montagu. ...

, then at the head of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, refused to promise him immediate command of a ship, and he resigned his commission in 1777, without having served during the American War of Independence

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, which he politically opposed.

Parliamentary career

At the 1774 general election Gordon was returned unopposed asMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Ludgershall. The pocket borough

A rotten or pocket borough, also known as a nomination borough or proprietorial borough, was a parliamentary borough or constituency in England, Great Britain, or the United Kingdom before the Reform Act 1832, which had a very small electorate ...

had been bought for him by General Fraser, to fend off Gordon's threat to oppose him in Inverness-shire

Inverness-shire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Nis) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. Covering much of the Highlands and Outer Hebrides, it is Scotland's largest county, though one of the smallest in popula ...

. Gordon was considered flighty, and was not looked upon as being of any importance. From the moment he entered parliament he was a strong critic of the government's colonial policy in regard to America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. He became a supporter of American independence and often spoke out in favour of the colonies.

His chances of building a political following in parliament were damaged by his inconsistency and his tendency to criticise all the major political factions. He was just as likely to attack the radical opposition spokesman Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

in a speech as he was to challenge Lord North, the Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

Prime Minister. His chances of being returned at the 1780 general election were overtaken by events. He remained close to political life, and after being acquitted at his trial in 1781, he declared his intention of standing for the City of London, but withdrew.

The Gordon Riots

In 1779 he organised, and made himself head of, the Protestant Association, formed to secure the repeal of the Papists Act 1778, which had restored limited civil rights to Roman Catholics willing to swear certain oaths of loyalty to the Crown. On 2 June 1780 he headed a crowd of around 50,000 people that marched in procession from St George's Fields just south of London to theHouses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

in order to present a huge petition against (partial) Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

. After the mob reached Westminster the "Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots of 1780 were several days of rioting in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. They began with a large and orderly protest against the Papists Act 1778, which was intended to reduce official discrimination against Briti ...

" began. Initially, the mob dispersed after threatening to force their way into the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, but reassembled soon afterwards and, over several days, destroyed several Roman Catholic chapels, pillaged the private dwellings of Catholics, set fire to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

, broke open all the other prisons, and attacked the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government o ...

and several other public buildings. The army was finally brought in to quell the unrest and killed or wounded around 450 people before they finally restored order.

For his role in instigating the riots, Lord George was charged with high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. He was comfortably imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and permitted to receive visitors, including the Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

leader Rev. John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English cleric, theologian, and evangelist who was a leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The societies he founded became the dominant form of the independent Meth ...

on Tuesday 19 December 1780 who may have shared the condemning opinion of his brother Charles Wesley

Charles Wesley (18 December 1707 – 29 March 1788) was an English leader of the Methodist movement. Wesley was a prolific hymnwriter who wrote over 6,500 hymns during his lifetime. His works include "And Can It Be", "Christ the Lord Is Risen T ...

.''The Feminist Companion to Literature in English'', eds Virginia Blain, Patricia Clements and Isobel Grundy (London: Batsford, 1990), p. 276.

Thanks to a strong defence by his cousin, Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine, he was acquitted on the grounds that he had had no treasonable intent.

Imprisonment

In 1786 he wasexcommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

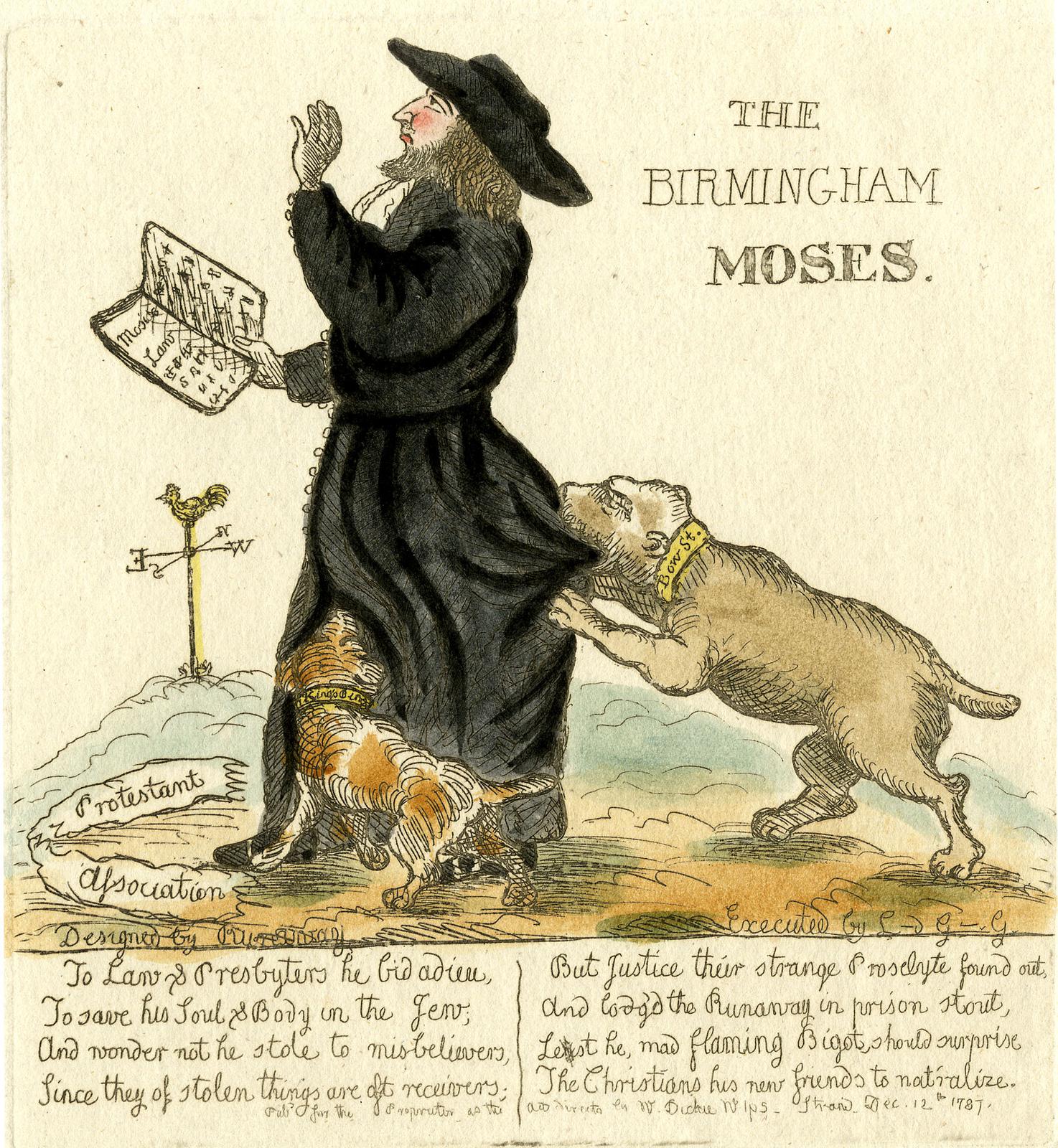

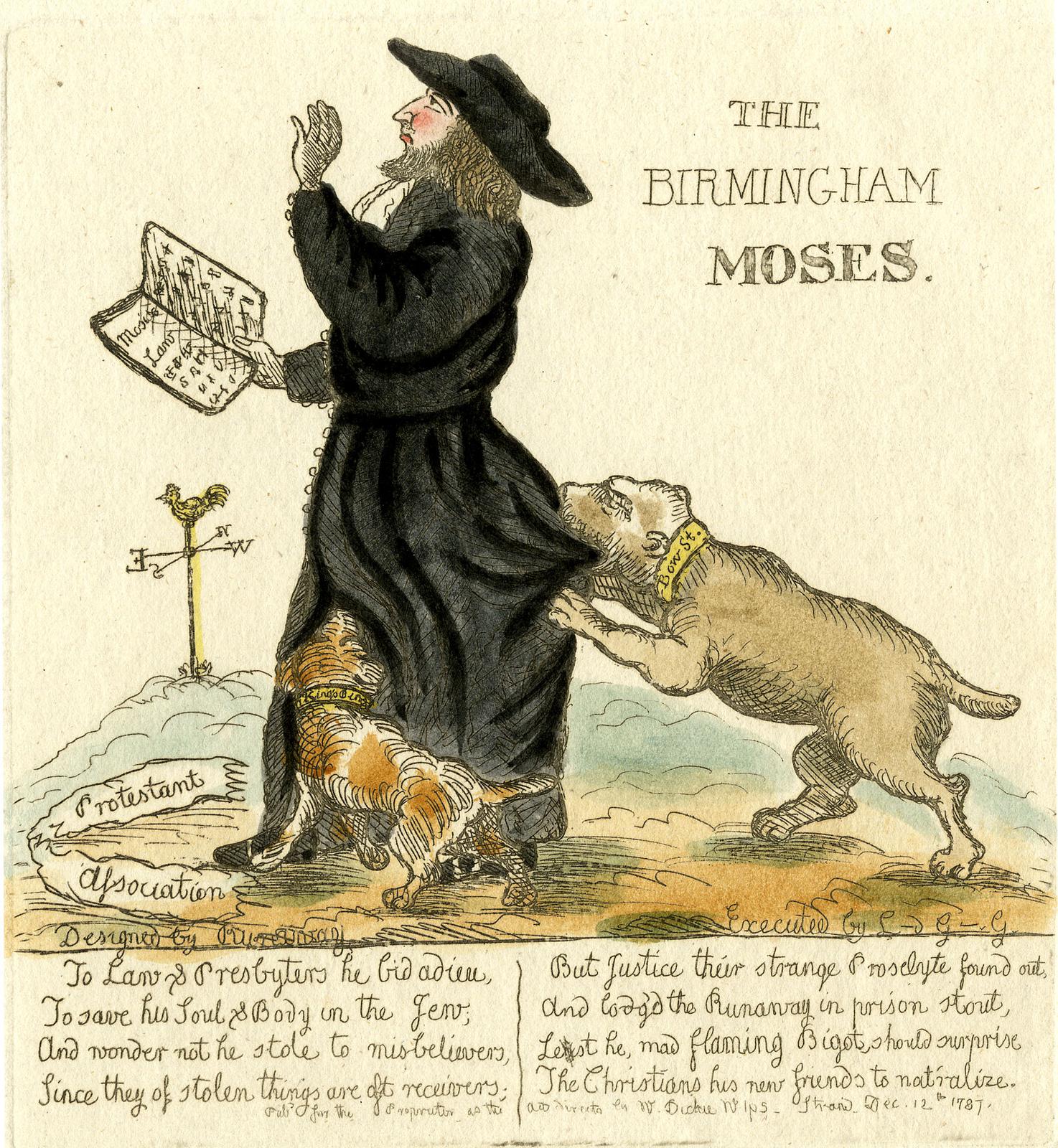

for refusing to bear witness in an ecclesiastical suit, and in 1787 he was convicted of defaming Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josèphe Jeanne (; ; née Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

, Jean-Balthazar d'Adhémar (the French ambassador to Great Britain) and the administration of justice in England. He was, however, permitted to withdraw from the court without bail, and made his escape to the Netherlands. On account of representations from the court of Versailles he was commanded to leave that country, and, returning to England, was apprehended in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

, and in January 1788 was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in Newgate and some harsh additional conditions.

Conversion to Judaism

In 1787, at the age of 36, Lord George Gordonconverted to Judaism

Conversion to Judaism ( he, גיור, ''giyur'') is the process by which non-Jews adopt the Jewish religion and become members of the Jewish ethnoreligious community. It thus resembles both conversion to other religions and naturalization. ...

in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

(though other sources report the conversion occurred slightly earlier when in Holland in the Netherlands), and underwent brit milah

The ''brit milah'' ( he, בְּרִית מִילָה ''bərīṯ mīlā'', ; Ashkenazi pronunciation: , " covenant of circumcision"; Yiddish pronunciation: ''bris'' ) is the ceremony of circumcision in Judaism. According to the Book of Genes ...

(ritual circumcision; circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Top ...

was rare in the England of his day) at the synagogue in Severn Street now next door to Singers Hill Synagogue

The Birmingham Hebrew Congregation, commonly known as the Singers Hill Synagogue, is an Orthodox Jewish synagogue in Birmingham, England. The synagogue is a Grade II* listed building, comprising 26, 26A and 26B Blucher Street in the city centre. ...

. He took the name of Yisrael bar Avraham Gordon ("Israel son of Abraham" Gordon—since Judaism regards a convert as the spiritual "son" of the Biblical Abraham). Gordon thus became what Judaism regards as, and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

call, a ''" Ger Tsedek"''—a righteous convert.

Not much is known about his life as a Jew in Birmingham, but the ''Bristol Journal'' of 15 December 1787 reported that Gordon had been living in Birmingham since August 1786:

He lived with a Jewish woman in the Froggery, a marshy area now under New Street station.

While in prison, Gordon lived the life of an Orthodox Jew

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on ...

, and he adjusted his prison life to his circumstances. He put on his ''tzitzit

''Tzitzit'' ( he, ''ṣīṣīṯ'', ; plural ''ṣīṣiyyōṯ'', Ashkenazi: '; and Samaritan: ') are specially knotted ritual fringes, or tassels, worn in antiquity by Israelites and today by observant Jews and Samaritans. are usual ...

'' and ''tefillin

Tefillin (; Modern Hebrew language, Israeli Hebrew: / ; Ashkenazim, Ashkenazic pronunciation: ), or phylacteries, are a set of small black leather boxes with leather straps containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah. Te ...

'' daily. He fasted when the ''halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'' (Jewish law) prescribed it, and likewise celebrated the Jewish holiday

Jewish holidays, also known as Jewish festivals or ''Yamim Tovim'' ( he, ימים טובים, , Good Days, or singular , in transliterated Hebrew []), are holidays observed in Judaism and by JewsThis article focuses on practices of mainst ...

s. He was supplied kosher meat and wine, and ''Shabbat challah, challos'' by prison authorities. The prison authorities permitted him to have a ''minyan

In Judaism, a ''minyan'' ( he, מניין \ מִנְיָן ''mīnyān'' , lit. (noun) ''count, number''; pl. ''mīnyānīm'' ) is the quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious obligations. In more traditional streams of Ju ...

'' on the Jewish Sabbath and to affix a '' mezuza'' on the door of his cell. The Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ ...

were also hung on his wall.

Gordon associated only with pious Jews; in his passionate enthusiasm for his new faith, he refused to deal with any Jew who compromised the

Gordon associated only with pious Jews; in his passionate enthusiasm for his new faith, he refused to deal with any Jew who compromised the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

's commandments. Although any non-Jew who desired to visit Gordon in prison (and there were many) was welcome, he requested that the prison guards admit Jews only if they had beards and wore head coverings.

He would often, in keeping with Jewish ''chesed'' (laws of mercy and charity), go into other parts of the prison to comfort prisoners by speaking with them and playing the violin. In keeping with '' tzedaka'' (charity) laws, he gave what little money he could to those in need.

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, in his novel ''Barnaby Rudge

''Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty'' (commonly known as ''Barnaby Rudge'') is a historical novel by British novelist Charles Dickens. ''Barnaby Rudge'' was one of two novels (the other was ''The Old Curiosity Shop'') that Dickens publ ...

'', which centres around the Gordon Riots, describes Gordon as a true ''tzadik

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. Th ...

'' (pious man) among the prisoners:

On 28 January 1793, Lord George Gordon's sentence expired and he had to appear to give claim to his future good behaviour. When appearing in court he was ordered to remove his hat, which he was using as a ''kippah

A , , or , plural ), also called ''yarmulke'' (, ; yi, יאַרמלקע, link=no, , german: Jarmulke, pl, Jarmułka or ''koppel'' ( yi, קאפל ) is a brimless cap, usually made of cloth, traditionally worn by Jewish males to fulfill the ...

'', but he refused to do so. The hat was then taken from him by force, but he covered his head with a night cap and bound it with a handkerchief. He defended his behaviour by saying "in support of the propriety of the creature having his head covered in reverence to the Creator." Before the court, he read a written statement in which he claimed that "he had been imprisoned for five years among murderers, thieves, etc., and that all the consolation he had arose from his trust in God."

Although his brothers, the 4th Duke of Gordon and Lord William Gordon, and his sister, Lady Westmoreland, offered to cover his bail, Gordon refused their help, saying that to "sue for pardon was a confession of guilt."

Death

In October 1793, Gordon caughttyphoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

, which had been raging in Newgate prison throughout that year. Christopher Hibbert

Christopher Hibbert MC (born Arthur Raymond Hibbert; 5 March 1924 – 21 December 2008) was an English author, historian and biographer. He has been called "a pearl of biographers" (''New Statesman'') and "probably the most widely-read popular ...

, another biographer, writes that scores of prisoners waited outside the door to his cell for news about his health; friends, regardless of the risk of infection, stood whispering in the room and praying for his recovery – but George "Yisrael bar Avraham" Gordon died on 1 November 1793 (26 Mar-Cheshvan 5554) at the age of 41.

Most likely fearing desecration, Gordon was not buried in a Jewish cemetery but in the detached burial ground of St James's Church, Piccadilly (an Anglican church from which he had been excommunicated.), which was located some way from the church, beside Hampstead Road, 900 yards north of Warren Street

Warren Street is a street in the London Borough of Camden that runs from Cleveland Street in the west to Tottenham Court Road in the east. Warren Street tube station is located at the eastern end of the street.

History

The street is crossed b ...

- it later became St James's Gardens but from June 2017 onwards its burials were reinterred elsewhere to make way for HS2 expansions to Euston station

Euston railway station ( ; also known as London Euston) is a central London railway terminus in the London Borough of Camden, managed by Network Rail. It is the southern terminus of the West Coast Main Line, the UK's busiest inter-city ra ...

.

Gordon's life story can be found in Yirmeyahu Bindman's dramatized biography, ''Lord George Gordon'' (1992), and a defence of his actions is undertaken in Robert Watson's ''The Life of Lord George Gordon, with a Philosophical Review of his Political Conduct'' (1795). He is also one of the subjects included by Hugh MacDiarmid in the volume, ''Scottish Eccentrics'' (1936). Historical accounts of Lord George Gordon can be found in '' The Annual Registers'' from 1780 to the year of his death.

See also

*Lewis Charles Levin

Lewis Charles Levin (November 10, 1808 – March 14, 1860) was an American politician, newspaper editor and anti-Catholic social activist. He was one of the founders of the American Party in 1842 and served as a member of the U. S. House of Rep ...

and the Philadelphia Nativist Riots

The Philadelphia nativist riots (also known as the Philadelphia Prayer Riots, the Bible Riots and the Native American Riots) were a series of riots that took place on May 68 and July 67, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States and the ...

References

*External links

Lord George Gordon and Cabalistic Freemasonry: Beating Jacobite Swords into Jacobin Ploughshares

by Marsha Keith Schuchard {{DEFAULTSORT:Gordon, Lord George 1751 births 1793 deaths Anglo-Scots George People excommunicated by the Church of England Converts to Judaism from Anglicanism English Jews Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1774–1780 Scottish Jews Younger sons of dukes Deaths from typhoid fever Infectious disease deaths in England Prisoners who died in England and Wales detention English people who died in prison custody British politicians convicted of crimes People acquitted of treason People educated at Eton College Persecution of Catholics