Lophelia pertusa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

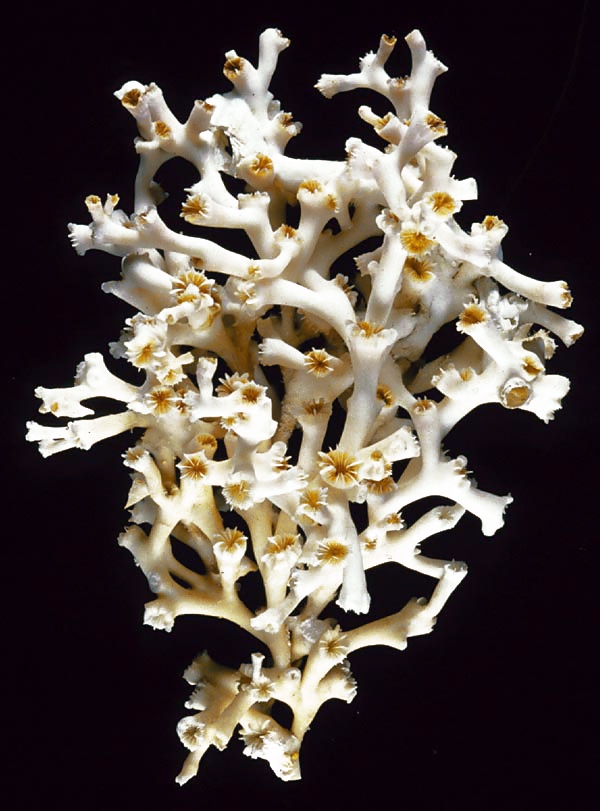

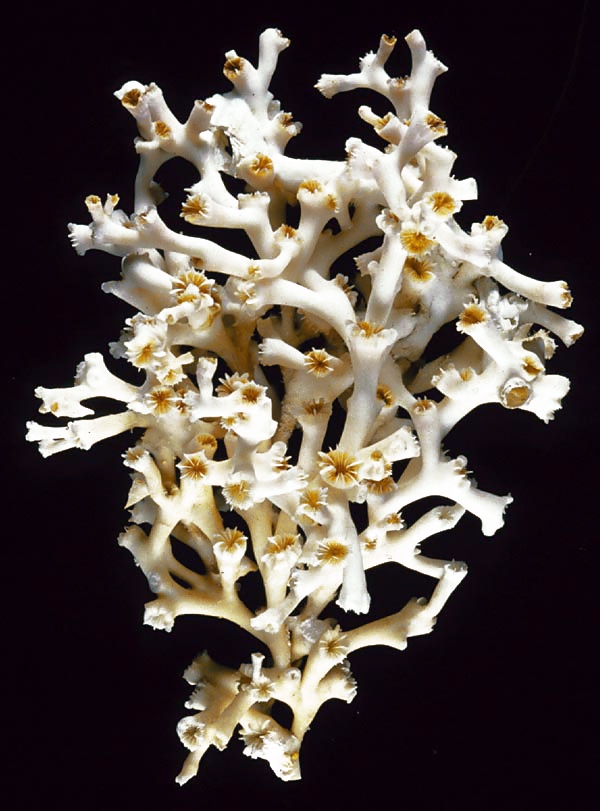

''Lophelia pertusa'', the only species in the genus ''Lophelia'', is a

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain  ''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef,

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef,

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that

Lophelia.org - Cold-water coral resource

{{Taxonbar, from1=Q1869773, from2=Q2703346 Caryophylliidae Monotypic cnidarian genera Corals described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Taxa named by Henri Milne-Edwards Taxa named by Jules Haime

cold-water coral

The habitat of deep-water corals, also known as cold-water corals, extends to deeper, darker parts of the oceans than tropical corals, ranging from near the surface to the abyss, beyond where water temperatures may be as cold as . Deep-water co ...

that grows in the deep waters throughout the North Atlantic ocean, as well as parts of the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

and Alboran Sea. Although ''L. pertusa'' reefs are home to a diverse community, the species is extremely slow growing and may be harmed by destructive fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

practices, or oil exploration and extraction.

Biology

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain

''Lophelia pertusa'' is a reef building, deep water coral, but it does not contain zooxanthella

Zooxanthellae is a colloquial term for single-celled dinoflagellates that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including demosponges, corals, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthellae are in the genus '' Sym ...

e, the symbiotic algae which lives inside most tropical reef building corals. ''Lophelia'' lives at a temperature range from about and at depths between and over , but most commonly at depths of , where there is no sunlight.

As a coral, it represents a colonial organism

In biology, a colony is composed of two or more conspecific individuals living in close association with, or connected to, one another. This association is usually for mutual benefit such as stronger defense or the ability to attack bigger prey.

...

, which consists of many individuals. New polyps

A polyp in zoology is one of two forms found in the phylum Cnidaria, the other being the medusa. Polyps are roughly cylindrical in shape and elongated at the axis of the vase-shaped body. In solitary polyps, the aboral (opposite to oral) end i ...

live and build upon the calcium carbonate skeletal remains of previous generations. Living coral ranges in colour from white to orange-red; each polyp has up to 16 tentacles and is a translucent pink, yellow or white. Unlike most tropical corals, the polyps are not interconnected by living tissue. Some colonies have larger polyps while others have small and delicate -looking ones. Radiocarbon dating indicates that some ''Lophelia'' reefs in the waters off North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and ...

may be 40,000 years old, with individual living coral bushes as much as 1,000 years old.

The colony grows by the bud

In botany, a bud is an undeveloped or embryonic shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of a stem. Once formed, a bud may remain for some time in a dormant condition, or it may form a shoot immediately. Buds may be spec ...

ding off of new polyps. Living polyps are present on the edges of dead coral and fragmentation of coral colonies provides one form of asexual reproduction. Each colony is either male or female and sexual reproduction occurs when these liberate sperm and oocyte

An oocyte (, ), oöcyte, or ovocyte is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The femal ...

s into the sea. The larvae do not have a feeding stage, but sustain themselves on their yolks and drift with the plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

, possibly for several weeks. When settling on the seabed, they undergo metamorphosis and develop into polyps, which then potentially start new colonies.

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef,

''Lophelia'' reefs can grow to high. The largest recorded ''Lophelia'' reef, Røst Reef

The Rost Reef ( no, Røstrevet) is a deep-water coral reef off the coast of the Lofoten islands in Nordland county, Norway. The reef was discovered in 2002, about west of the island of Røstlandet. It extends over a length of about , and has a ...

, measures and lies at a depth of off the Lofoten Islands

Lofoten () is an archipelago and a traditional district in the county of Nordland, Norway. Lofoten has distinctive scenery with dramatic mountains and peaks, open sea and sheltered bays, beaches and untouched lands. There are two towns, Svolvæ ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

. When this is seen in terms of a growth rate of around 1 mm per year, the great age of these reefs becomes apparent.

Polyps at the end of branches feed by extending their tentacle

In zoology, a tentacle is a flexible, mobile, and elongated organ present in some species of animals, most of them invertebrates. In animal anatomy, tentacles usually occur in one or more pairs. Anatomically, the tentacles of animals work ma ...

s and straining plankton from the seawater. They are able to ingest particles of up to 2 cm, and are able to discriminate between food and sediment using their chemoreceptors to differentiate between the two. Growth of polyps depends on environmental factors such as food availability, water quality, and how the water flows.

''L. pertusa'' are considered to be opportunistic feeders since they feed on particles of organic matter that have been broken down. Hence, the spring bloom of phytoplankton and subsequent zooplankton

Zooplankton are the animal component of the planktonic community ("zoo" comes from the Greek word for ''animal''). Plankton are aquatic organisms that are unable to swim effectively against currents, and consequently drift or are carried along by ...

blooms provide the main source of nutrient input to the deep sea. This rain of dead plankton is visible on photographs of the seabed and stimulates a seasonal cycle of growth and reproduction in ''Lophelia''. This cycle is recorded in patterns of growth, and can be studied to investigate climatic variation in the recent past.

Conservation status

''L. pertusa'' was listed underCITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

Appendix II in January 1990, meaning that the United Nations Environmental Programme

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is responsible for coordinating responses to environmental issues within the United Nations system. It was established by Maurice Strong, its first director, after the United Nations Conference on th ...

recognizes that this species is not necessarily currently threatened with extinction but that it may become so in the future. CITES is a means of restricting international trade in endangered species, which is not a major threat to the survival of ''L. pertusa''. The OSPAR Commission for the protection of the marine environment of the North-East Atlantic have recognized ''Lophelia pertusa'' reefs as a threatened habitat in need of protection.

Main threats come from destruction of reefs by heavy deep-sea trawl

Trawling is a method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch different speci ...

nets, targeting redfish

Redfish is a common name for several species of fish. It is most commonly applied to certain deep-sea rockfish in the genus ''Sebastes'', red drum from the genus '' Sciaenops'' or the reef dwelling snappers in the genus '' Lutjanus''. It is also a ...

or grenadiers. The heavy metal "doors", which hold the mouth of the net open, and the "footline", which is equipped with large metal "rollers", are dragged along the sea bed, and have a highly damaging effect on the coral. Because the rate of growth is so slow, it is unlikely that this practice will prove to be sustainable.

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The

Scientists estimate that trawling has damaged or destroyed 30%–50% of the Norwegian shelf coral area. The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea

The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES; french: Conseil International de l'Exploration de la Mer, ''CIEM'') is a regional fishery advisory body and the world's oldest intergovernmental science organization. ICES is headqu ...

, the European Commission

The European Commission (EC) is the executive of the European Union (EU). It operates as a cabinet government, with 27 members of the Commission (informally known as "Commissioners") headed by a President. It includes an administrative body ...

’s main scientific advisor on fisheries and environmental issues in the northeast Atlantic, recommend mapping and then closing all of Europe’s deep corals to fishing trawlers.

In 1999, the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries closed an area of at Sula, including the large reef, to bottom trawling. In 2000, an additional area closed, covering about . An area of about enclosing the Røst Reef

The Rost Reef ( no, Røstrevet) is a deep-water coral reef off the coast of the Lofoten islands in Nordland county, Norway. The reef was discovered in 2002, about west of the island of Røstlandet. It extends over a length of about , and has a ...

closed to bottom trawling in 2002. Bottom trawling leads to siltation or sand deposition, which involves the disturbance of underlying sediments and nutrients. This harmful process destroys and decreases the growth of coral reefs, affecting the expansion of polyp budding.

In recent years, environmental organizations such as Greenpeace have argued that exploration for oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

on the north west continental shelf slopes of Europe should be curtailed due to the possibility that is it damaging to the ''Lophelia'' reefs - conversely, ''Lophelia'' has recently been observed growing on the legs of oil installations, specifically the Brent Spar

Brent Spar, or Brent E, was a North Sea oil storage and tanker loading buoy in the Brent oilfield, operated by Shell UK. With the completion of a pipeline connection to the oil terminal at Sullom Voe in Shetland, the storage facility had cont ...

rig which Greenpeace campaigned to remove. At the time, the growth of ''L. pertusa'' on the legs of oil rigs was considered unusual, although recent studies have shown this to be a common occurrence, with 13 of 14 North Sea oil

North Sea oil is a mixture of hydrocarbons, comprising liquid petroleum and natural gas, produced from petroleum reservoirs beneath the North Sea.

In the petroleum industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea ...

rigs examined having ''L. pertusa'' colonies. The authors of the original work suggested that it may be better to leave the lower parts of such structures in place— a suggestion opposed by Greenpeace campaigner Simon Reddy, who compared it to " umpinga car in a wood – moss would grow on it, and if I was lucky a bird may even nest in it. But this is not justification to fill our forests with disused cars".

Recovery of damaged ''L.pertusa'' will be a slow process not only due to its slow growth rate, but also due to its low rates of colonization and recolonization process. This is because even if ''L.pertusa'' produces a dispersive larva, a sediment free surface is required to initiate a new settlement. Moreover, excessive sedimentation and chemical contaminants will negatively impact the larvae, even when they are available in large numbers.

As ocean temperatures continue to rise due to global warming, climate change is another deadly factor that threatens the existence of ''L. pertusa''. Although ''L. pertusa'' can survive changes in oxygen levels during periods of hypoxia and anoxia, they are vulnerable to sudden temperature changes. These fluctuations in temperature affect their metabolic rate, which has detrimental consequences regarding their energy input and growth.

Ecological significance

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that

''Lophelia'' beds create a specialized habitat favored by some species of deep water fishes. Surveys have recorded that conger eel

''Conger'' ( ) is a genus of marine congrid eels. It includes some of the largest types of eels, ranging up to 2 m (6 ft) or more in length, in the case of the European conger. Large congers have often been observed by divers during ...

s, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachi ...

s, grouper

Groupers are fish of any of a number of genera in the subfamily Epinephelinae of the family Serranidae, in the order Perciformes.

Not all serranids are called "groupers"; the family also includes the sea basses. The common name "grouper" is ...

s, hake

The term hake refers to fish in the:

* Family Merlucciidae of northern and southern oceans

* Family Phycidae (sometimes considered the subfamily Phycinae in the family Gadidae) of the northern oceans

Hake

Hake is in the same taxonomic order ( ...

and the invertebrate community consisting of brittle star

Brittle stars, serpent stars, or ophiuroids (; ; referring to the serpent-like arms of the brittle star) are echinoderms in the class Ophiuroidea, closely related to starfish. They crawl across the sea floor using their flexible arms for locomot ...

s, molluscs, amphipods

Amphipoda is an order of malacostracan crustaceans with no carapace and generally with laterally compressed bodies. Amphipods range in size from and are mostly detritivores or scavengers. There are more than 9,900 amphipod species so far describ ...

and crabs reside on these beds. High densities of smaller fish such as hatchetfish and lanternfish

Lanternfishes (or myctophids, from the Greek μυκτήρ ''myktḗr'', "nose" and ''ophis'', "serpent") are small mesopelagic fish of the large family Myctophidae. One of two families in the order Myctophiformes, the Myctophidae are represent ...

have been recorded in the waters over ''Lophelia'' beds, indicating they may be important prey items for the larger fish below.

''L. pertusa'' also forms a symbiosis with polychaete '' Eunice norvegica.'' It is suggested that ''E. norvegica'' positively influences ''L.pertusa'' by forming connecting tubes, which are later calcified, in order to strengthen the reef frameworks. While ''E. norvegica'' requires partial consumption of the food obtained by ''L. pertusa'', ''E. norvegica'' aids in cleaning the living coral framework and protecting it from potential predators.

Foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

nRange

''L. pertusa'' has been reported fromAnguilla

Anguilla ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin. The terr ...

, Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

, Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = "Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, es ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Cape Verde, Colombia, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ge ...

, Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

, Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, French Southern Territories

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (french: Terres australes et antarctiques françaises, TAAF) is an Overseas Territory (french: Territoire d'outre-mer or ) of France. It consists of:

# Adélie Land (), the French claim on the continent ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders ...

, Grenada, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Jamaica, Japan, Madagascar, Mexico, Montserrat, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, Portugal, Puerto Rico, Saint Helena, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Senegal, South Africa, United Kingdom, United States of America, U.S. Virgin Islands and Wallis and Futuna Islands.As reported by CITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

and the UNEP, and as such, is incomplete, and affected by development of marine science in that country, and effort put into surveying for it.

References

External links

Lophelia.org - Cold-water coral resource

{{Taxonbar, from1=Q1869773, from2=Q2703346 Caryophylliidae Monotypic cnidarian genera Corals described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Taxa named by Henri Milne-Edwards Taxa named by Jules Haime