List of rebellions in China on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is an incomplete list of some of the

rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

s, revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

s and revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

s that have occurred in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

.

Zhou dynasty

*Rebellion of the Three Guards

The Rebellion of the Three Guards (), or less commonly the Wu Geng Rebellion (), was a civil war, instigated by an alliance of discontent Zhou princes, Shang loyalists, vassal states and other non-Zhou peoples against the Western Zhou governmen ...

(late 11th century BC) was a three-year rebellion of the Shang

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and ...

and three uncles of King Cheng of Zhou

King Cheng of Zhou (), personal name Ji Song (姬誦), was the second king of the Chinese Zhou dynasty. The dates of his reign are 1042–1021 BCE or 1042/35–1006 BCE. His parents were King Wu of Zhou and Queen Yi Jiang (邑姜).

King Cheng w ...

against their nephew and his regent, the Duke of Zhou

Dan, Duke Wen of Zhou (), commonly known as the Duke of Zhou (), was a member of the royal family of the early Zhou dynasty who played a major role in consolidating the kingdom established by his elder brother King Wu. He was renowned for actin ...

.

* Compatriots Rebellion (842 BC) was an uprising against King Li of Zhou

King Li of Zhou (died in 828 BC) (), personal name Ji Hu, was the tenth king of the Chinese Zhou Dynasty. Estimated dates of his reign are 877–841 BC or 857–842 BC (''Cambridge History of Ancient China'').

King Li was a corrupt and decadent ...

, ending with the King's exile, establishing the interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

Gonghe Regency

The Gonghe Regency () was an interregnum period in Chinese history from 841 BC to 828 BC, after King Li of Zhou was exiled by his nobles during the Compatriots Rebellion, when the Chinese people rioted against their old corrupt king. It lasted u ...

until King Xuan of Zhou

__NOTOC__

King Xuan of Zhou, personal name Ji Jing, was the eleventh king of the Chinese Zhou Dynasty. Estimated dates of his reign are 827/25–782 BC.

He worked to restore royal authority after the Gong He interregnum. He fought the 'Western ...

took the throne.

Qin dynasty

* TheDazexiang Uprising

The Chen Sheng and Wu Guang uprising (), July–December 209 B.C., was the first uprising against the Qin dynasty following the death of Qin Shi Huang. Led by Chen Sheng and Wu Guang, the uprising helped overthrow the Qin and paved the way for ...

(; July – December 209 BC) was the first uprising against Qin rule following the death of Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of " king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Empero ...

. Chen Sheng

Chen Sheng (died January 208 BC), also known as Chen She ("She" being his courtesy name), posthumously known as Prince Yin, was the leader of the Dazexiang Uprising, the first rebellion against the Qin Dynasty. It occurred during the reign ...

and Wu Guang

Wu Guang (, died December 209 BC or January 208 BC) was a leader of the first rebellion against the Qin Dynasty during the reign of the Second Qin Emperor.

Life

Wu Guang was born in Yangxia (陽夏; present-day Taikang County, Zhoukou, Hen ...

were both army officers who were ordered to lead their bands of commoner soldiers north to participate in the defense of Yuyang (漁陽). However, they were stopped halfway in Dazexiang, Qixian (modern Suzhou, Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

) by a severe rainstorm and flooding. Harsh Qin law stated that anyone who showed up late for a government job would be executed, regardless of the nature of the delay. Chen and Wu realized they could never make it on time, and decided to organize a band that would rebel against the government, and declared they would rather fight than accept execution. They became the center of armed uprisings all over China, and in a few months, their strength congregated to around ten thousand men, composed mostly of discontented peasants. However, on the battlefield, they were no match for the highly professional Qin soldiers, and the uprising was in trouble in less than a year.

* Liu Bang's Insurrection (206 BC) was a popular revolt that overthrew the Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

and, after a period of contention, crowned Liu Bang

Emperor Gaozu of Han (256 – 1 June 195 BC), born Liu Bang () with courtesy name Ji (季), was the founder and first emperor of the Han dynasty, reigning in 202–195 BC. His temple name was "Taizu" while his posthumous name was Empe ...

the first emperor of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

.

Western Han dynasty

* TheRebellion of the Seven States

The Rebellion of the Seven States or Revolt of the Seven Kingdoms () took place in 154 BC against the Han dynasty of China by its regional semi-autonomous kings, to resist the emperor's attempt to centralize the government further.

Background ...

or Kingdoms (, 154 BC) was a revolt by members of the Han imperial family against attempts to centralize the government under Emperor Jing.

At the beginning of the Han dynasty, Emperor Gao had made many of his relatives princes of certain sections, about one-third to one-half of the empire. This was an attempt to consolidate Liu family rule over the parts of China that were not ruled directly from the capital under the junxian (郡縣) commandery system. During the reign of Emperor Wen, these princes were still setting their own laws, but they were also casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejecte ...

their own coins (albeit with Emperor Wen's approval) and collecting their own taxes. Many princes were effectively ignoring the imperial government's authority within their own principalities. When Jing became emperor in 157 BC, the rich Principality of Wu was especially domineering. Liu Pi, therefore, started a rebellion. The princes participating were: Liu Pi, the Prince of Wu; Liu Wu, the Prince of Chu; Liu Ang, the Prince of Jiaoxi Xing; Liu Sui (劉遂), the Prince of Zhao; Liu Xiongqu (劉雄渠), the Prince of Jiaodong (roughly modern Qingdao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

, Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

); Liu Xian (劉賢), the Prince of Zaichuan (roughly part of modern Weifang

Weifang () is a prefecture-level city in central Shandong province, People's Republic of China. The city borders Dongying to the northwest, Zibo to the west, Linyi to the southwest, Rizhao to the south, Qingdao to the east, and looks out to ...

, Shandong); and Liu Piguang (劉辟光), the Prince of Jinan (roughly modern Jinan

Jinan (), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanization of Chinese, romanized as Tsinan, is the Capital (political), capital of Shandong province in East China, Eastern China. With a population of 9.2 million, it is the second-largest city i ...

, Shandong)

Two other principalities agreed to join— Qi (modern central Shandong) and Jibei (modern northwestern Shandong)— but neither actually did. Liu Jianglü (劉將閭), the Prince of Qi, changed his mind at the last moment and chose to resist the rebellion forces. Liu Zhi (劉志), the Prince of Jibei, was put under house arrest by the commander of his guards and prevented from joining the rebellion. Three other princes were persuaded to join, but either refused, or did not actually agree to join Liu An (劉安), the Prince of Huainan (roughly modern Lu'an

Lu'an (), is a prefecture-level city in western Anhui province, People's Republic of China, bordering Henan to the northwest and Hubei to the southwest. As of the 2020 census, it had a total population of 4,393,699 inhabitants whom 1,752,537 liv ...

, Anhui

Anhui , (; formerly romanized as Anhwei) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the East China region. Its provincial capital and largest city is Hefei. The province is located across the basins of the Yangtze Riv ...

).

Other participants included Liu Ci (劉賜), the Prince of Lujiang (roughly modern Chaohu

Chaohu () is a county-level city of Anhui Province, People's Republic of China, it is under the administration of the prefecture-level city of Hefei. Situated on the northeast and southeast shores of Lake Chao, from which the city was named, Ch ...

, Anhui), and Liu Bo (劉勃), the Prince of Hengshan (roughly part of modern Lu'an, Anhui). The princes also requested help from the southern independent kingdoms of Donghai (modern Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Ji ...

) and Minyue

Minyue () was an ancient kingdom in what is now the Fujian province in southern China. It was a contemporary of the Han dynasty, and was later annexed by the Han empire as the dynasty expanded southward. The kingdom existed approximately fro ...

(modern Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its ...

), and the powerful northern Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

. Donghai and Minyue sent troops to participate in the campaign, but Xiongnu, after initially promising to do so as well, did not. The seven princes, as part of their political propaganda, claimed that Chao Cuo was aiming to wipe out the principalities, and that they would be satisfied if Chao were executed.

Xin dynasty

*Lülin

Lulin (, 'green forest') was one of two major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang's short-lived Xin dynasty in the modern southern Henan and northern Hubei regions. These two regions banded together to pool their strengths, their c ...

(綠林) or Lülin Force (綠林兵) refers, as an umbrella term, to one of the two major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the th ...

's Xin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Pin ...

in the modern southern Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is a ...

and northern Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

region who banded together to pool their strengths, and whose collective strength eventually led to the downfall of the Xin dynasty and the establishment of a temporary reinstatement of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

under Liu Xuan ( Gengshi Emperor). Many Lülin leaders became important members of Gengshi Emperor's government, but infighting and incompetence (both of the emperor and his officials) in governing the empire led to the fall of the regime after only two years, paving the way for the eventual rise for Liu Xiu (Emperor Guangwu

Emperor Guangwu of Han (; 15 January 5 BC – 29 March AD 57), born Liu Xiu (), courtesy name Wenshu (), was a Chinese monarch. He served as an emperor of the Han dynasty by restoring the dynasty in AD 25, thus founding the Eastern Han (Later ...

). The name Lülin came from the Lülin Mountains (in modern Yichang

Yichang (), alternatively romanized as Ichang, is a prefecture-level city located in western Hubei province, China. It is the third largest city in the province after the capital, Wuhan and the prefecture-level city Xiangyang, by urban populati ...

, Hubei), where the rebels had their stronghold for a while.

In AD 17, Jing Province

Jingzhou or Jing Province was one of the Nine Provinces of ancient China referenced in Chinese historical texts such as the '' Tribute of Yu'', ''Erya'' and '' Rites of Zhou''.

Jingzhou became an administrative division during the reign of Empe ...

(modern Hubei, Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangx ...

, and southern Henan) was suffering from a famine that was greatly exacerbated by the corruption and incompetence of Xin officials. The victims of the famine were reduced to consuming wild plants, and even those were in short supply, causing the suffering people to attack each other. Two men named Wang Kuang (王匡) and Wang Feng (王鳳), both from Xinshi (新市, in modern Jingmen

Jingmen () is a prefecture-level city in central Hubei province, People's Republic of China. Jingmen is within an area where cotton and oil crops are planted. The population of the prefecture is 2,873,687 (2010 population census). The urban area ...

, Hubei), became arbiters in some of these disputes, and they became the leaders of the starving people. They were later joined by many others, including Ma Wu (馬武), Wang Chang (王常), and Cheng Dan (成丹). Within a few months, 7,000 to 8,000 men gathered together under their commands. They had their base at Lülin Mountain, and their modus operandi

A ''modus operandi'' (often shortened to M.O.) is someone's habits of working, particularly in the context of business or criminal investigations, but also more generally. It is a Latin phrase, approximately translated as "mode (or manner) of o ...

was to attack and pillage villages far from the cities for food. This carried on for several years, during which they grew to tens of thousands in size.

Wang sent messengers issuing pardons in hopes of causing these rebels to disband. Once the messengers returned to the Xin capital Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

, some honestly reported that the rebels gathered because the harsh laws made it impossible for them to make a living, and therefore they were forced to rebel. Some, in order to flatter Wang Mang, told him that these were simply evil resistors who needed to be killed, or that this was a temporary phenomenon. Wang listened to those who flattered him and generally relieved those who told the truth from their posts. Wang made no further attempts to pacify the rebels, but instead decided to suppress them by force. In reality, the rebels were forced into rebellion to survive, and they were hoping that eventually, when the famine was over, they could return home to farm. As a result, they never dared to attack cities.

In AD 21, the governor of Jing Province mobilized 20,000 soldiers to attack the Lülin rebels, and a battle was fought at Yundu (雲杜), a major victory for the rebels, who killed thousands of government soldiers and captured their food supply and arms. When the governor tried to retreat, his route was temporarily cut off by Ma Wu who allowed him to escape, not wanting to offend the government more than the rebels had done already. Instead, the Lülin rebels roved near the area, capturing many women, and then returning to the Lülin Mountain. By this point, they had 50,000 men.

* Chimei (赤眉) refers, as an umbrella term, to one of the two major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the th ...

's Xin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Pin ...

, initially active in the modern Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

and northern Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

region, that eventually led to Wang Mang's downfall by draining his resources, allowing the leader of the other movement (the Lülin

Lulin (, 'green forest') was one of two major agrarian rebellion movements against Wang Mang's short-lived Xin dynasty in the modern southern Henan and northern Hubei regions. These two regions banded together to pool their strengths, their c ...

), Liu Xuan (Gengshi Emperor) to overthrow Wang and temporarily establish an incarnation of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

under him. Eventually, Chimei forces overthrew Gengshi Emperor and placed their own puppet emperor, Liu Penzi

Liu Penzi (; 10 AD - after 27 AD)

was a puppet emperor placed on the Han dynasty throne temporarily by the Red Eyebrows (Chimei) rebels after the collapse of the Xin dynasty, from 25 to 27 AD. Liu Penzi and his two brothers were forced into t ...

, on the throne briefly, before the Chimei leaders' incompetence in ruling the territories under their control, which matched their brilliance on the battlefield, caused the people to rebel against them, forcing them to try to withdraw home. When their path was blocked by Liu Xiu

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often voc ...

(Emperor Guangwu)'s newly established Eastern Han regime, they surrendered to him.

Circa AD 17, due to Wang Mang's incompetence in ruling—particularly in the implementation of his land reform policy—and a major Yellow River

The Yellow River or Huang He (Chinese: , Mandarin: ''Huáng hé'' ) is the second-longest river in China, after the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest river system in the world at the estimated length of . Originating in the Bayan Ha ...

flood affecting modern Shandong and northern Jiangsu regions, the people, who could no longer subsist on farming, were forced into rebellion to try to survive. The rebellions were numerous and fractured.

Eastern Han dynasty

* TheYellow Turban Rebellion

The Yellow Turban Rebellion, alternatively translated as the Yellow Scarves Rebellion, was a peasant revolt in China against the Eastern Han dynasty. The uprising broke out in 184 CE during the reign of Emperor Ling. Although the main rebelli ...

or Yellow Scarves Rebellion (; AD 184) was a peasant rebellion against Emperor Ling. It is named for the scarves the rebels wrapped around their heads. They were associated with secret Taoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Tao ...

societies, and the rebellion marked an important point in the history of Taoism. The rebellion is the opening event in the historical novel ''Romance of the Three Kingdoms

''Romance of the Three Kingdoms'' () is a 14th-century historical novel attributed to Luo Guanzhong. It is set in the turbulent years towards the end of the Han dynasty and the Three Kingdoms period in Chinese history, starting in 184 AD ...

'' by Luo Guanzhong

Luo Ben (c. 1330–1400, or c.1280–1360), better known by his courtesy name Guanzhong (Mandarin pronunciation: ), was a Chinese writer who lived during the Ming dynasty. He was also known by his pseudonym Huhai Sanren (). Luo was attri ...

.

A major cause of the Yellow Turban Rebellion was an agrarian crisis where famine forced many farmers and former military settlers in the north to seek employment in the south, whose large landowners took advantage of the labor surplus and amassed large fortunes. The situation was further aggravated by smaller floods along the lower course of the Yellow River. Further pressure was added on the peasants by high taxes imposed on them in order to build fortifications along the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

, and garrisons against foreign infiltrations and invasions. From AD 170 on, landlords and peasants formed irregular armed bands, setting the stage for class conflict.

At the same time, the Han dynasty showed internal weakness. The power of the landowners had been a problem for a long time already (see Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the th ...

), but in the run-up to the Yellow Turban Rebellion, the court eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millenni ...

s, in particular, gained considerable influence over the emperor, which they abused to enrich themselves. Ten of the most powerful eunuchs formed a group known as the Ten Regular Attendants and the emperor referred to one of them, Zhang Rang

The Ten Attendants, also known as the Ten Eunuchs, were a group of influential eunuch-officials in the imperial court of Emperor Ling ( 168–189) in Eastern Han China. Although they are often referred to as a group of 10, there were actually 12 ...

, as his "foster father." Consequently, the government was widely regarded as corrupt and incapable. Against this backdrop, the famines and floods were seen as an indication that a decadent emperor had lost his mandate of heaven

The Mandate of Heaven () is a Chinese political philosophy that was used in ancient and imperial China to legitimize the rule of the King or Emperor of China. According to this doctrine, heaven (天, '' Tian'') – which embodies the nat ...

.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion was led by Zhang Jiao

Zhang Jue (; died October 184) was a Chinese military general and rebel. He was the leader of the Yellow Turban Rebellion during the late Eastern Han dynasty of China. He was said to be a follower of Taoism and a sorcerer. His name is sometimes ...

(or Zhang Jue) and his two younger brothers Zhang Bao and Zhang Liang, who were born in Julu District, Ye Prefecture. The brothers had founded a Taoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Tao ...

religious sect in Shandong Province. They considered themselves followers of the "Way of Supreme Peace" and venerated the deity '' Huang-Lao'', who according to Zhang Jiao had given him a sacred book called the ''Crucial Keys to the Way of Peace'' (''Tai Ping Yao Shu''). Zhang Jiao was said to be a sorcerer and styled himself as the Great Teacher. The sect propagated the principles of equal rights of all peoples and equal distribution of land; when the rebellion was proclaimed, the sixteen-word slogan was created by Zhang Jiao: 苍天已死,黄天当立,岁在甲子,天下大吉 ("The Blue Sky (ie. the Han dynasty) has perished, the Yellow Sky (ie. the rebellion) will soon rise; in this year of Jia Zi, let there be prosperity in the world!")

* The Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion (AD 184) was a religious rebellion instigated by Zhang Lu, the grandson of the Taoist leader Zhang Daoling

Zhang Ling (; traditionally 34–156), courtesy name Fuhan (), was a Chinese religious leader who lived during the Eastern Han Dynasty credited with founding the Way of the Celestial Masters sect of Taoism, which is also known as the Way of the ...

. The name of the rebellion derives from the name of his movement, the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice (), in turn, named for the amount of rice paid as dues or for cures.

Early in the 2nd century AD, Zhang Daoling used his popularity as a faith healer and religious leader to organize a theological movement against the Han dynasty from the widespread poverty and corruption that oppressed the peasants under its rule. He gathered many followers from the Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

area by not only providing a source of hope for the disparaged, but also by reforming religious practices into a more acceptable format. This created one of the first organized religious movements in China.

In AD 184, the successor of his son Zhang Heng

Zhang Heng (; AD 78–139), formerly romanized as Chang Heng, was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman who lived during the Han dynasty. Educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, he achieved success as an astronomer, mat ...

, his grandson Zhang Lu, revolted against the Han dynasty and created his own state, Zhang Han. This state continued for over 30 years until Zhang Lu's defeat and surrender to the general Cao Cao

Cao Cao () (; 155 – 15 March 220), courtesy name Mengde (), was a Chinese statesman, warlord and poet. He was the penultimate grand chancellor of the Eastern Han dynasty, and he amassed immense power in the dynasty's final years. As one o ...

. After Zhang Lu's surrender, he relocated to the Han court where he continued to live until the Han dynasty was replaced by the Cao Wei

Wei ( Hanzi: 魏; pinyin: ''Wèi'' < : *''ŋjweiC'' < Sun En Rebellion () was a rebellion led by Sun En, the nephew of an executed southern

"Chongming Island"

. China Travel Depot, 17 August 2011. Accessed 18 Jan 2015.

The

The

The

The

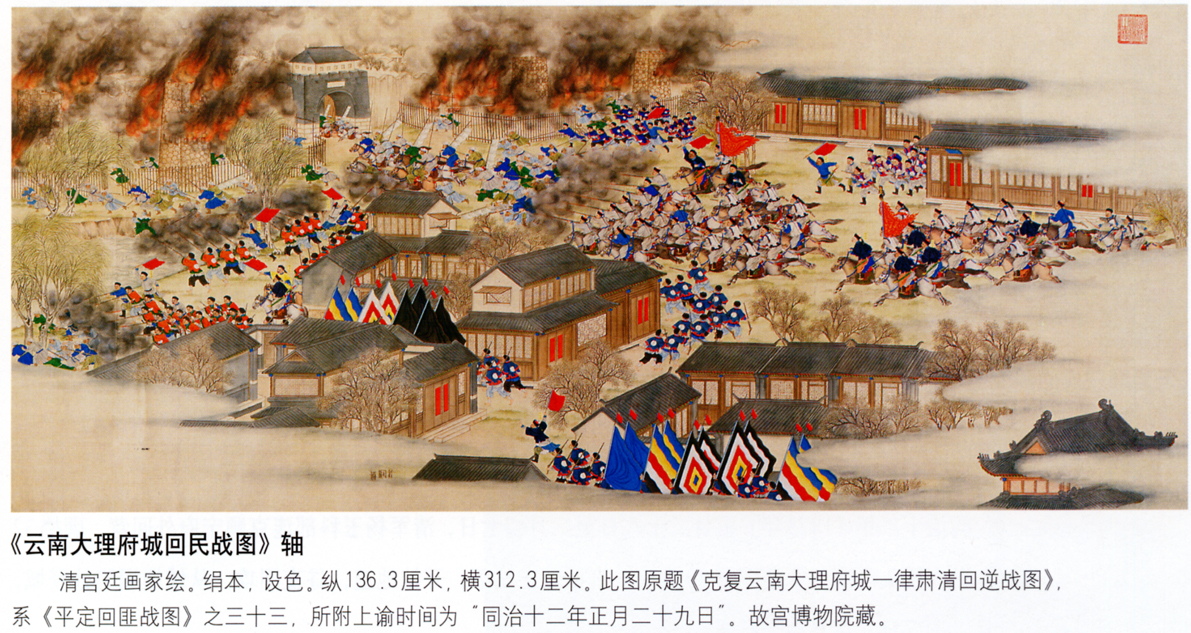

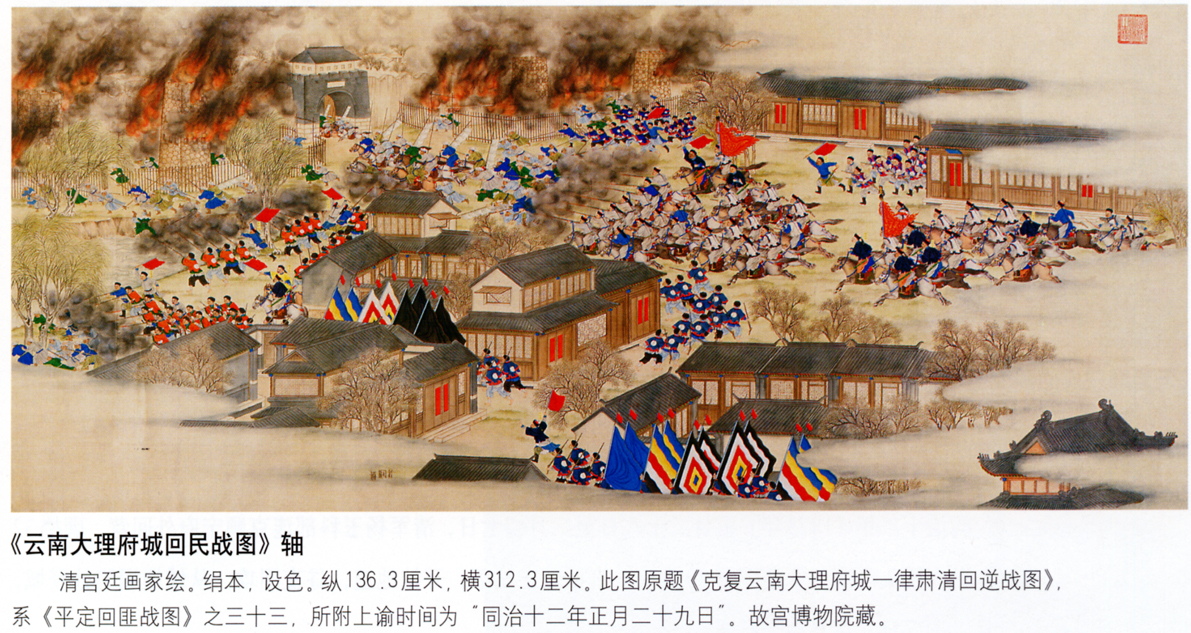

The Du Wenxiu Rebellion, or Panthay Rebellion (1856–1872) was a separatist movement of

The Du Wenxiu Rebellion, or Panthay Rebellion (1856–1872) was a separatist movement of

Taoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Tao ...

leader. The rebels planned to flee to Penglai Island

Penglai () is a legendary land of Chinese mythology. It is known in Japanese mythology as Hōrai.McCullough, Helen. ''Classical Japanese Prose'', p. 570. Stanford Univ. Press, 1990. .

Location

According to the ''Classic of Mountains and Seas' ...

after their success and the campaign was notable for its major naval battles and the government's dependence on Liu Laozhi, a general risen from among common stock. Their discarded rafts are sometimes credited with the early formation of Chongming Island

Chongming, formerly known as Chungming, is an alluvial island at the mouth of the Yangtze River in eastern China covering as of 2010. Together with the islands Changxing and Hengsha, it forms Chongming District, the northernmost area of the ...

in northern Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

.Li, Jack"Chongming Island"

. China Travel Depot, 17 August 2011. Accessed 18 Jan 2015.

Tang dynasty

* TheAn Shi Rebellion

The An Lushan Rebellion was an uprising against the Tang dynasty of China towards the mid-point of the dynasty (from 755 to 763), with an attempt to replace it with the Yan dynasty. The rebellion was originally led by An Lushan, a general office ...

(; 756–763) was a rebellion by An Lushan

An Lushan (; 20th day of the 1st month 19 February 703 – 29 January 757) was a general in the Tang dynasty and is primarily known for instigating the An Lushan Rebellion.

An Lushan was of Sogdian and Göktürk origin,Yang, Zhijiu, "An Lush ...

and Shi Siming

Shi Siming () (19th day of the 1st month, 703? – 18 April 761), or Shi Sugan (), was a Chinese military general, monarch, and politician during the Tang Dynasty who followed his childhood friend An Lushan in rebelling against Tang, and who la ...

against the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

. It was also known as the Tianbao Rebellion () from the name of the Chinese era during which it began.

The rebellion spanned the reigns of three emperors. The first, Emperor Xuanzong, escaped to Sichuan. Along the way, his soldiers demanded the death of an official, Yang Guozhong, and his cousin, Consort Yang. Emperor Suzong, a son of Emperor Xuanzong, was proclaimed emperor by the Tang army and eunuchs, while another group of local officials and Confucian literati proclaimed another prince as the new emperor in Jinling (present-day Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Map Romanization, alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and t ...

).

It was begun by An Lushan in the 14th year of Tianbao but, after the assassination of his son An Qingxu

An Qingxu (安慶緒) (730s – 10 April 759), né An Renzhi (安仁執), was a son of An Lushan, a general of the Chinese Tang Dynasty who rebelled and took the imperial title, and then established his own state of Yan. An Qingxu served as th ...

, the revolt was led by his former subordinate Shi Siming. The rebellion was suppressed during the reign of Emperor Daizong

Emperor Daizong of Tang (9 January 727 According to Daizong's biography in the '' Old Book of Tang'', he was born on the 13th day in the 12th month of the 14th year of the Kaiyuan era of Tang Xuanzong's reign. This date corresponds to 9 Jan 727 ...

by generals Pugu Huai'en Pugu Huai'en () (died September 27, 765), formally the Prince of Da'ning (大寧王), was a general of the Chinese Tang dynasty of Tiele ancestry. He was instrumental in the final suppression of the Anshi Rebellion, but rebelled against Emperor D ...

, Guo Ziyi

Guo Ziyi (Kuo Tzu-i; Traditional Chinese: 郭子儀, Simplified Chinese: 郭子仪, Hanyu Pinyin: Guō Zǐyí, Wade-Giles: Kuo1 Tzu3-i2) (697 – July 9, 781), posthumously Prince Zhōngwǔ of Fényáng (), was a Chinese military general and po ...

and Li Guangbi

Li Guangbi (李光弼) (708 – August 15, 764), formally Prince Wumu of Linhuai (臨淮武穆王), was a Chinese military general, monarch, and politician during the Tang dynasty. He was of ethnic Khitan ancestry, who was instrumental in Tang's ...

. Although successful at suppressing the rebellion, the Tang dynasty was badly weakened by it, and in its remaining years was troubled by persistent warlordism.

*The Huang Chao Rebellion ( or (; 875 - 884) was a rebellion by Huang Chao

Huang Chao (835 – July 13, 884) was a Chinese smuggler, soldier, and rebel, and is most well known for being the leader of a major rebellion that severely weakened the Tang dynasty.

Huang was a salt smuggler before joining Wang Xianzhi's ...

.

Yuan dynasty

* TheRed Turban Rebellion

The Red Turban Rebellions () were uprisings against the Yuan dynasty between 1351 and 1368, eventually leading to its collapse. Remnants of the Yuan imperial court retreated northwards and is thereafter known as the Northern Yuan in historiog ...

() was an uprising against the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

-led Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

. Since the 1340s, the Yuan dynasty was experiencing problems. The Yellow River flooded constantly, and other natural disasters also occurred. At the same time, the Yuan government required considerable military expenditure to maintain its vast empire. This was solved mostly through additional taxation that fell mainly on the Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

population which constituted the lowest two of the four castes of people under Yuan rule — much influenced by the White Lotus Society members that targeted the ruling Yuan government.

Ming dynasty

*Li Zicheng

Li Zicheng (22 September 1606 – 1645), born Li Hongji, also known by the nickname, Dashing King, was a Chinese peasant rebel leader who overthrew the Ming dynasty in 1644 and ruled over northern China briefly as the emperor of the short-li ...

's rebellion was a peasant rebellion aimed at the overthrow of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

; it led to the establishment of the Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

-led Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. Li Zicheng began recruiting troops at Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

in Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

province, and later went on to gain power throughout northeastern China. From 1620, towards the end of the Wanli Emperor

The Wanli Emperor (; 4 September 1563 – 18 August 1620), personal name Zhu Yijun (), was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigned from 1572 to 1620. "Wanli", the era name of his reign, literally means "ten thousand calendars". He was th ...

's reign, social and economic conditions under Ming rule worsened drastically. Li Zicheng did not become the emperor, but he paved the way for the rising of the new Qing dynasty, after overthrowing the Ming emperor by capturing Beijing. The Qing troops, arriving from the northeast (originally from Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

) were allied with Wu Sangui

Wu Sangui (; 8 June 1612 – 2 October 1678), courtesy name Changbai () or Changbo (), was a notorious Ming Dynasty military officer who played a key role in the fall of the Ming dynasty and the founding of the Qing dynasty in China. In Chinese ...

, a former Ming general, an alliance which eventually led to the defeat of Li Zicheng, though the impact of his rebellion was tremendous.

Qing dynasty

Revolt of the Three Feudatories

TheRevolt of the Three Feudatories

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories, () also known as the Rebellion of Wu Sangui, was a rebellion in China lasting from 1673 to 1681, during the early reign of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). The revolt was ...

was led by three territories () in southern China bestowed by the early Manchu rulers on three Han Chinese generals — Wu Sangui

Wu Sangui (; 8 June 1612 – 2 October 1678), courtesy name Changbai () or Changbo (), was a notorious Ming Dynasty military officer who played a key role in the fall of the Ming dynasty and the founding of the Qing dynasty in China. In Chinese ...

, Geng Jingzhong, and Shang Zhixin

Shang Zhixin (; 1636 – 1680) was a major figure in the early Qing Dynasty, known for his role in the Revolt of the Three Feudatories. He was Prince of Pingnan (平南王, "Prince who Pacifies the South"), inheriting his position from his father ...

. In the second half of the 17th century, they revolted against the Qing government. This rebellion came as the Qing rulers were establishing themselves after their conquest of China in 1644 and was the last serious threat to their ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

'' until the 19th-century conflicts that ultimately brought about the end of the dynasty in 1912. The revolt was followed by almost a decade of civil war which extended across the breadth of China.

In 1655, the Qing government granted Wu Sangui, a man to whom they were indebted for the conquest of China, both civil and military authority over the province of Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

. In 1662, after the execution of Zhu Youlang

The Yongli Emperor (; 1623–1662; reigned 18 November 1646 – 1 June 1662), personal name Zhu Youlang, was a royal member to the imperial family of Ming dynasty, and the fourth and last commonly recognised emperor of the Southern Ming, reign ...

, the last claimant to the Ming throne, Wu was also given jurisdiction over Guizhou

Guizhou (; Postal romanization, formerly Kweichow) is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in the Southwest China, southwest region of the China, People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Guiyang, in the center of the pr ...

. In the next decade he consolidated his power, and by 1670 his influence had spread to include much of Hunan, Sichuan, Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

and even Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

. Two other powerful defected military leaders also developed similar powers: Shang Zhixin in Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020 ...

and Geng Jingzhong in Fujian. They ruled their feudatories (territories) as their own domains and the Qing government had virtually no control over the provinces in the south and southwest.

By 1672, the Kangxi Emperor

The Kangxi Emperor (4 May 1654– 20 December 1722), also known by his temple name Emperor Shengzu of Qing, born Xuanye, was the third emperor of the Qing dynasty, and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, reigning from 1661 to ...

had determined that these feudatories were a threat to the Qing regime. In 1673, Shang Zhixin submitted a memorial requesting permission to retire and in August of the same year, a similar request arrived from Wu Sangui, designed to test the court's intentions. The Kangxi Emperor went against the majority view in the Council of Princes and High Officials and accepted the request. News of Wu's rebellion reached Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), Chinese postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the Capital city, capital of the China, People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's Li ...

in January 1674.

White Lotus Rebellion

TheWhite Lotus Rebellion

The White Lotus Rebellion (, 1794–1804) was a rebellion initiated by followers of the White Lotus movement during the Qing dynasty of China. Motivated by millenarian Buddhists who promised the immediate return of the Buddha, it erupted out of ...

(1796–1804) was an anti-Qing uprising that occurred during the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

.

It broke out among impoverished settlers in the mountainous region that separates Sichuan province from Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

and Shaanxi provinces. It apparently began as a tax protest led by the White Lotus Society, a secret religious society that forecasted the advent of the Buddha Maitreya

Maitreya (Sanskrit: ) or Metteyya (Pali: ), also Maitreya Buddha or Metteyya Buddha, is regarded as the future Buddha of this world in Buddhist eschatology. As the 5th and final Buddha of the current kalpa, Maitreya's teachings will be aimed a ...

, advocated the restoration of the Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

, and promised personal salvation to its followers. At first, the Qing government, under the control of Heshen

Heshen (; ; 1 July 1750 – 22 February 1799) of the Manchu Niohuru clan, was an official of the Qing dynasty favored by the Qianlong Emperor and called the most corrupt official in Chinese history. After the death of Qianlong, the Jiaqing Em ...

, sent inadequate and inefficient imperial forces to suppress the ill-organized rebels. On assuming effective power in 1799, however, the Jiaqing Emperor (r. 1796-1820) overthrew Heshen's clique and gave support to the efforts of the more vigorous Qing commanders as a way of restoring discipline and morale. A systematic program of pacification followed in which the populace was resettled in hundreds of stockaded villages and organized into a militia by the name of ''tuanlian

Yong Ying (, literally "brave camps") were a type of regional army that emerged in the 19th century in the Qing dynasty army, which fought in most of China's wars after the Opium War and numerous rebellions exposed the ineffectiveness of the Manch ...

''. In its last stage, the Qing suppression policy combined pursuit and extermination of rebel guerrilla bands with a program of amnesty for deserters. Although the Qing finally crushed the rebellion, the myth of the military invincibility of the Manchus was shattered, perhaps contributing to the greater frequency of rebellions in the 19th century.

Eight Trigrams uprising of 1813

The Eight Trigrams uprising of 1813 broke out in China under the Qing dynasty. The rebellion was started by some elements of the millenarian Tianli Sect (天理教) or Heavenly Principle Sect, which was a branch of the White Lotus Sect. Led by Lin Qing (林清; 1770–1813) and Li Wencheng, the revolt occurred in the Zhili, Shandong, and Henan provinces of China. In 1812, the leaders of the Eight Trigram Sect (Bagua jiao) also known as the Sect of Heavenly Order (Tianli jiao) announced that leader Li Wencheng was a 'true lord of the Ming' and declared 1813 as the year for rebellion, while Lin Qing declared himself the reincarnation of Maitreya, the prophesied future Buddha in Buddhism, using banners with the inscription "Entrusted by Heaven to Prepare the Way", a reference to the popular novel Water Margin. They considered him sent by the Eternal Unborn Mother of esoteric Chinese religions, to remove the Qing dynasty whom they regarded as having lost the Mandate of Heaven to rule. The third leader was Feng Keshan, who was called the "King of Earth", Li titled the "King of Men", and Lin referred to as "King of Heaven". The group won support from several powerful Eunuchs in the Forbidden City. On 15 September 1813, the group attacked the imperial palace in Beijing. The rebels made it into the city, and may have been successful in overthrowing the Qing had not Prince Mianning—the future emperor—used his forbidden musket to repel the invaders. The rebellion is seen as being similar to the previous White Lotus Rebellion, with the former being of religious intent and the latter leaders of the Eight Trigram appearing more interested in personal power by overthrowing the Qing dynasty.Taiping Rebellion

The

The Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion, also known as the Taiping Civil War or the Taiping Revolution, was a massive rebellion and civil war that was waged in China between the Manchu-led Qing dynasty and the Han, Hakka-led Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. It last ...

(1850–1864), usually known in Chinese after the name of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, later shortened to the Heavenly Kingdom or Heavenly Dynasty, was an unrecognised rebel kingdom in China and a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy from 1851 to 1864, supporting the overthrow of the Q ...

() proclaimed by the rebels, was a rebellion in southern China inspired by a Hakka

The Hakka (), sometimes also referred to as Hakka Han, or Hakka Chinese, or Hakkas are a Han Chinese subgroup whose ancestral homes are chiefly in the Hakka-speaking provincial areas of Guangdong, Fujian, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Sichuan, Hunan, Zhej ...

named Hong Xiuquan

Hong Xiuquan (1 January 1814 – 1 June 1864), born Hong Huoxiu and with the courtesy name Renkun, was a Chinese revolutionary who was the leader of the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. He established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdo ...

, who had claimed that he was the brother of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

. Most sources put the total deaths at about 20 million, although some claim tolls as high as 50 million. Altogether, "some historians have estimated that the combination of natural disasters combined with the political insurrections may have cost on the order of 200 million Chinese lives between 1850–1865." The figure is unlikely, as it is approximately half the estimated population of China in 1851.

Hong Xiuquan gathered his support in a time of considerable turmoil. The country had suffered a series of natural disasters, economic problems and defeats at the hands of the Western powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania.

, problems that the ruling Qing dynasty did little to lessen. Anti-Qing sentiment was strongest in the south, and it was these disaffected that joined Hong. The sect extended into militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

in the 1840s, initially against banditry. The persecution of the sect was the spur for the struggle to develop into guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

and then into full-blown war. The revolt began in Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

province. In early January 1851, a ten-thousand-strong rebel army routed Qing imperial forces at the town of Jintian in the Jintian Uprising. The Qing forces attacked but were driven back. In August 1851, Hong declared the establishment of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with himself as absolute ruler. The revolt spread northwards with great rapidity. 500,000 Taiping soldiers took Nanjing in March 1853, killing 30,000 Qing soldiers and slaughtering thousands of civilians. The city became the movement's capital and was renamed Tianjing (lit. "Heavenly Capital"; not to be confused with Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popu ...

) until its recapture.

Nian Rebellion

The

The Nian Rebellion

The Nian Rebellion () was an armed uprising that took place in northern China from 1851 to 1868, contemporaneously with Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) in South China. The rebellion failed to topple the Qing dynasty, but caused immense economic ...

(; 1851–1868) was a large armed uprising that took place in northern China. The rebellion failed to topple the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

, but caused immense economic devastation and loss of life that became one of the major long-term factors in the collapse of the Qing regime.

The Nian movement was formed in the late 1840s by Zhang Lexing

Zhang Lexing (, 1810 – 1863) was a Chinese guerrilla leader during the Nian Rebellion in China.

Zhang was originally a landlord and a member of a powerful lineage involved in salt-smuggling. In 1852 he was chosen to lead the Nian, and in 1856 ...

and, by 1851, numbered approximately 40,000. Unlike the Taiping Rebellion, though, the Nian movement initially had no clear goals or objectives aside from criticism of the Qing government. However, the Nian rebels were provoked into taking direct action against the Qing regime following a series of ecological disasters. In 1851, the Yellow River burst its banks, flooding hundreds of thousands of square miles and causing immense loss of life. The Qing government slowly began cleaning up after the disaster, but were unable to provide effective aid as government finances had been drained during the Opium War with the British, and the ongoing slaughter of the Taiping Rebellion. The damage created by the disaster had still not been repaired when, in 1855, the river burst its banks again, drowning thousands and devastating the fertile province of Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

. At the time, the Qing government was trying to negotiate a deal with the Western powers, and as state finances had been so severely depleted, the regime was unable to provide effective relief aid. This enraged the Nian movement, who blamed the Westerners for contributing to China's troubles, and increasingly viewed the Qing government as incompetent and cowardly in the face of the Western powers.

In 1855, Zhang Lexing took direct action by launching attacks against government troops in central China. By the summer, the fast-moving Nian cavalry, well-trained and fully equipped with modern firearms, had cut the lines of communication between Beijing and the Qing armies fighting the Taiping rebels in the south. Qing forces were badly overstretched as rebellions broke out across China, allowing the Nian armies to conquer large tracts of land and gain control over economically vital areas. The Nian fortified their captured cities and used them as bases to launch cavalry attacks against Qing troops in the countryside, prompting local towns to fortify themselves against Nian raiding parties. This resulted in constant fighting which devastated the previously rich provinces of Jiangsu and Hunan.

In early 1856, the Qing government sent the Mongol general Sengge Rinchen

Sengge Rinchen (1811 – 18 May 1865) or Senggelinqin ( mn, Сэнгэринчен, ᠰᠡᠩᠭᠡᠷᠢᠨᠴᠢᠨ) was a Mongol nobleman and general who served under the Qing dynasty during the reigns of the Daoguang, Xianfeng and Tongzhi em ...

, who had recently crushed a large Taiping rebel army, to defeat the Nian. Sengge Rinchen's army captured several fortified cities and destroyed most of the Nian infantry, and killed Zhang Lexing himself in an ambush. However, the Nian movement survived as Taiping commanders arrived to take control of the Nian forces, and the bulk of the Nian cavalry remained intact. Sengge Rinchen's infantry-based army could not stop the fast moving cavalry from devastating the countryside and launching surprise attacks on Qing troops. In 1865, Sengge Rinchen and his bodyguards were ambushed by Nian troops and killed, depriving the government of its best military commander. The Qing regime sent general Zeng Guofan

Zeng Guofan, Marquis Yiyong (; 26 November 1811 – 12 March 1872), birth name Zeng Zicheng, courtesy name Bohan, was a Chinese statesman and military general of the late Qing dynasty. He is best known for raising and organizing the Xiang ...

to take command of Qing imperial forces, providing him with modern artillery and weapons, purchased from the Europeans at extortionate prices. Zeng's army set about building canals and trenches to hem in the Nian cavalry — an effective, but slow and expensive method. Zeng was removed from the post after the Nian rebels broke one of his defense fronts. Generals Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=李鴻章; also Li Hung-chang; 15 February 1823 – 7 November 1901) was a Chinese politician, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in important ...

and Zuo Zongtang

Zuo Zongtang, Marquis Kejing ( also spelled Tso Tsung-t'ang; ; November 10, 1812 – September 5, 1885), sometimes referred to as General Tso, was a Chinese statesman and military leader of the late Qing dynasty.

Born in Xiangyin County, ...

were put in charge of the suppression. In late 1866, the Nian movement split into two — east Nian stayed in central China and west Nian sneaked close to Beijing. By late 1867, Li and Zuo's troops had recaptured much territory from the Nian rebels, and in early 1868, the movement was crushed by the combined forces of imperial troops and the Ever Victorious Army.

Du Wenxiu Rebellion

The Du Wenxiu Rebellion, or Panthay Rebellion (1856–1872) was a separatist movement of

The Du Wenxiu Rebellion, or Panthay Rebellion (1856–1872) was a separatist movement of Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Hui in western Yunnan, led by Du Wenxiu

Du Wenxiu (, Xiao'erjing: ) (1823 to 1872) was the Chinese Muslim leader of the Panthay Rebellion, an anti-Qing revolt in China during the Qing dynasty. Du had ethnic Hui ancestry.

Early life and background

Born in Yongchang (now Baoshan, Y ...

(born Sulayman ibn `Abd ar-Rahman).

Du claimed the title of ''Qa´id Jami al-Muslimin'' ("Leader of the Community of Muslims"). He was known in English as the Sultan of Dali upon the city's capture. It became the base for the rebels, who declared themselves "Pingnan" (). The rebels besieged the city of Kunming

Kunming (; ), also known as Yunnan-Fu, is the capital and largest city of Yunnan province, China. It is the political, economic, communications and cultural centre of the province as well as the seat of the provincial government. The headquar ...

four times (1857, 1861, 1863, and 1868) and briefly held the city during the third attempt. Later, as Qing forces began to gain the upper hand against the rebellion, the rebels sent a letter to Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, asking the British for formal recognition and for military assistance; the British demurred. The rebellion was eventually suppressed by Qing troops, who killed and posthumously decapitated Du. The brutal suppression led to many Hui people fleeing to neighboring countries bordering Yunnan. Surviving Huis escaped to Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist s ...

, forming the basis of a minority Chinese Hui population in those nations. Hundreds of thousands of Hui people were massacred or died in these purges.

The rebellion had a significant negative impact on the Burmese Konbaung dynasty

The Konbaung dynasty ( my, ကုန်းဘောင်ခေတ်, ), also known as Third Burmese Empire (တတိယမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်) and formerly known as the Alompra dynasty (အလောင်းဘ ...

. After losing lower Burma to the British, Burma lost access to vast tracts of rice-growing land. Not wishing to upset China, the Burmese kingdom agreed to refuse trade with the Hui rebels in accordance with China's demands. Without the ability to import rice from China, Burma was forced to import rice from the British. In addition, the Burmese economy had relied heavily on cotton exports to China, and suddenly lost access to the vast Chinese market.

Dungan revolts

In theJahriyya revolt

In the Jahriyya revolt () of 1781 sectarian violence between two suborders of the Naqshbandi Sufis, the Jahriyya Sufi Muslims and their rivals, the Khafiyya Sufi Muslims, led to Qing intervention to stop the fighting between the two, which in tu ...

sectarian violence between two suborders of the Naqshbandi

The Naqshbandi ( fa, نقشبندی)), Neqshebendi ( ku, نهقشهبهندی), and Nakşibendi (in Turkish) is a major Sunni order of Sufism. Its name is derived from Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari. Naqshbandi masters trace their ...

Sufis, the Jahriyya Sufi Muslims and their rivals, the Khafiyya Sufi Muslims, led to a Jahriyya Sufi Muslim rebellion which the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in China crushed with the help of the Khafiyya Sufi Muslims.

The First Dungan Revolt or Muslim Rebellion (; 1862–1877), known in China as the Hui Minority War, was an uprising by members of the Muslim Hui community in Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

, Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

, and Ningxia

Ningxia (,; , ; alternately romanized as Ninghsia), officially the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR), is an autonomous region in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. Formerly a province, Ningxia was incorporated into Gansu in 1 ...

.

Chinese Muslims had been traveling to West Asia for many years prior to the Hui Minorities' War. Some of them had adopted radical Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

Islamic teachings referred to as New Teachings. There had been attempted uprisings by followers of these New Teachings in 1781 and 1783. In 1862 the prestige of the Qing dynasty was low and their armies were busy elsewhere. In 1867 the Qing government sent one of their best officials, Zuo Zongtang, a hero of the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion, to Shaanxi. His forces were ordered to help put down the Nian Rebellion, and he was unable to deal with the Muslim rebels until December 1868. Zuo's approach was to rehabilitate the region by promoting agriculture, especially cotton and grain, as well as supporting orthodox Confucian education. Due to the poverty of the region, Zuo had to rely on financial support from outside the North-West. After building up enough grain reserves to feed his army, Zuo attacked the most important Muslim leader, Ma Hualong

Ma Hualong () (died March 2, 1871), was the fifth leader (, ''jiaozhu'') of the Jahriyya, a Sufi order (''menhuan'') in northwestern China.Dillon (1999), pp. 124-126

From the beginning of the anti-Qing Muslim Rebellion in 1862, and until his ...

. Ma was besieged in the city of Jinjibao for sixteen months before surrendering in March 1871. Zuo sentenced Ma and over eighty of his officials to death by slicing. Thousands of Muslims were exiled to different parts of China. Despite repeated offers of amnesty, many Muslims continued to resist until the fall of Suzhou in Gansu. The failure of the uprising in 1873 led to some immigration of Hui people into Russia. The descendants of the immigrants continue to live in the border region of Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

, and Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

.

The Second Dungan Revolt (1895–1896), known in China as the Second Hui Minority War, was a second Muslim revolt against the Qing. They were defeated by loyalist Muslim troops.

Boxer Rebellion

TheBoxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an Xenophobia, anti-foreign, anti-colonialism, anti-colonial, and Persecution of Christians#China, anti-Christian uprising in China ...

() or Uprising (; November 1899 –September 7, 1901) was a revolt against European commercial, political, religious, and technological influence in China. By August 1900, over 230 foreigners, thousands of Chinese Christians

Christianity in China has been present since at least the 3rd century, and it has gained a significant amount of influence during the last 200 years.

While Christianity may have existed in China before the 3rd century, evidence of its existe ...

, an unknown number of rebels and sympathizers and other Chinese were killed in the revolt and its suppression.

In 1840, the First Opium War

The First Opium War (), also known as the Opium War or the Anglo-Sino War was a series of military engagements fought between Britain and the Qing dynasty of China between 1839 and 1842. The immediate issue was the Chinese enforcement of the ...

broke out, and China was defeated by Britain. In view of the weakness of the Qing government, Britain and other nations such as France, Russia and Japan started to exert influence over China. Due to their inferior army and navy, the Qing dynasty was forced to sign many agreements which became known as the Unequal Treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

. These include the Treaty of Nanking

The Treaty of Nanjing was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the Unequal Treaties.

In the ...

(1842), the Treaty of Aigun

The Treaty of Aigun (Russian: Айгунский договор; ) was an 1858 treaty between the Russian Empire and the Qing dynasty that established much of the modern border between the Russian Far East and China by ceding much of Manchur ...

(1858), the Treaty of Tientsin

The Treaty of Tientsin, also known as the Treaty of Tianjin, is a collective name for several documents signed at Tianjin (then romanized as Tientsin) in June 1858. The Qing dynasty, Russian Empire, Second French Empire, United Kingdom, and t ...

(1858), the Convention of Peking

The Convention of Peking or First Convention of Peking is an agreement comprising three distinct treaties concluded between the Qing dynasty of China and Great Britain, France, and the Russian Empire in 1860. In China, they are regarded as amo ...

(1860), the Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

(1895), and the Second Convention of Peking (1898).

Such treaties were regarded as grossly unfair by many Chinese, whose prestige was sorely damaged by the treaties, as foreigners were perceived to receive special treatment compared to Chinese. Rumours circulated of foreigners committing crimes as a result of agreements between foreign and the Chinese governments over how foreigners in China should be prosecuted. In Guizhou, local officials were reportedly shocked to see a cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, t ...

using a sedan chair

The litter is a class of wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for the transport of people. Smaller litters may take the form of open chairs or beds carried by two or more carriers, some being enclosed for protection from the e ...

decorated in the same manner as one reserved for the governor. The Catholic Church's prohibition on some Chinese rituals and traditions was another issue of contention. Thus in the late 19th century such feelings increasingly resulted in civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

and violence towards both foreigners and Chinese Christians.

The rebellion was initiated by a society known as the Boxers (Chinese: Righteous Harmony Society), a group which initially opposed—but later reconciled itself to—the Qing dynasty. The Boxer Rebellion was concentrated in northern China where the European powers had begun to demand territorial, rail and mining concessions. Germany responded to the killing of two missionaries in Shandong province in November 1897 by seizing the port of Qingdao. A month later a Russian naval squadron took possession of Lushun, in southern Liaoning

Liaoning () is a coastal province in Northeast China that is the smallest, southernmost, and most populous province in the region. With its capital at Shenyang, it is located on the northern shore of the Yellow Sea, and is the northernmo ...

. Britain and France followed, taking possession of Weihai

Weihai (), formerly called Weihaiwei (), is a prefecture-level city and major seaport in easternmost Shandong province. It borders Yantai to the west and the Yellow Sea to the east, and is the closest Chinese city to South Korea.

Weihai's popul ...

and Zhanjiang

Zhanjiang (), historically spelled Tsamkong, is a prefecture-level city at the southwestern end of Guangdong province, People's Republic of China, facing Haikou city to the south.

As of the 2020 census, its population was 6,981,236 (6,994,832 ...

respectively.

Xinhai Revolution

TheXinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of ...

() was a republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

revolution which overthrew the Qing dynasty and led to the establishment of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. The revolution ended the monarchy which had a history for 4000 years in China and replaced it with a republic, with democratic ideals. The ensuing revolutionary war lasted from October 10, 1911, and ended upon the formation of the Republic of China on February 12, 1912. Since 1911 is a Xinhai Year in the sexagenary cycle

The sexagenary cycle, also known as the Stems-and-Branches or ganzhi ( zh, 干支, gānzhī), is a cycle of sixty terms, each corresponding to one year, thus a total of sixty years for one cycle, historically used for recording time in China and t ...

of the Chinese calendar

The traditional Chinese calendar (also known as the Agricultural Calendar ��曆; 农历; ''Nónglì''; 'farming calendar' Former Calendar ��曆; 旧历; ''Jiùlì'' Traditional Calendar ��曆; 老历; ''Lǎolì'', is a lunisolar calendar ...

, this is how Xinhai Revolution had got its name.

The revolution began with the armed Wuchang Uprising and the spread of republican insurrection through the southern provinces, and culminated in the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

after lengthy negotiations between rival imperial and republican regimes based in Beijing and Nanjing respectively.

The revolution inaugurated a period of struggle over China's eventual constitutional form, which saw two brief monarchical restorations and successive periods of political fragmentation before the Republic's final establishment.

The Xinhai Revolution is commemorated as the National Day of the Republic of China, also known as Double Ten Day

The National Day of the Republic of China ( zh, 中華民國的國慶日) or the Taiwan National Day, also referred to as Double Ten Day or Double Tenth Day, is a public holiday on 10 October, now held annually in Taiwan (officially the Republi ...

(雙十節). Today the National Day is mainly celebrated in Taiwan