List of Spanish inventions and discoveries on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following list is composed of items, techniques and processes that were invented by or discovered by people from

* ''Telekino'', pioneering of

* ''Telekino'', pioneering of

* Synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA) by

* Synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA) by

Gladius hispaniensis: an archaeological view from Iberia

1997 * Gladius Hispanensis (antennae swords) - Swords adopted by the Romans after the second Punic war. The Iberian sword was considered superior to that of the Romans. * Guerrilla warfare developed in Spain during the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian peninsula. *

* Modern rules of chess. Although chess has its origins in India, the modern rules of chess have their origin Spain. It is still under debate whether the rules were invented in the Islamic period or after the Christian reconquest of Toledo.

* El Ajedrecista, invention of the automatic chess by engineer and computer pioneer Leonardo Torres Quevedo (1852–1936) ''Torres and his remarkable automatic devices''. Issue 2079 of Scientific American, 1915

* The first

* Modern rules of chess. Although chess has its origins in India, the modern rules of chess have their origin Spain. It is still under debate whether the rules were invented in the Islamic period or after the Christian reconquest of Toledo.

* El Ajedrecista, invention of the automatic chess by engineer and computer pioneer Leonardo Torres Quevedo (1852–1936) ''Torres and his remarkable automatic devices''. Issue 2079 of Scientific American, 1915

* The first

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

Spain was an important center of knowledge during the medieval era

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. While most of western and southern Europe suffered from the collapse of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

, although declining, some regions of the former empire, Hispania

Hispania ( la, Hispānia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hisp ...

(the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

), southern Italy, and the remainder of the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire, did not to suffer from the full impact of the so-called Dark Ages when education collapsed with the collapse of the empire and most knowledge was lost. The Islamic conquests of places such as Egypt, which was a major part of the Byzantine Empire, and other places which were centers of knowledge in earlier times, gave the Muslims access to knowledge from many cultures which they translated into Arabic and recorded in books for the use of their own educated elites, who flourished in this period, and took with them to the Hispania after it fell under Muslim control. Much of this knowledge was later translated by Christian and Jewish scholars in the Christian kingdoms of the Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

from Arabic into Latin, and from there it spread through Europe.

Inventions and discoveries from the Golden Age of Al Andalus

''Note: Although these inventions were created on the Iberian Peninsula, that does not mean they were not made by people of Spanish heritage due to the area being part of the Islamic Empire.'' * Alcohol distillation *Mercuric oxide

Mercury(II) oxide, also called mercuric oxide or simply mercury oxide, is the inorganic compound with the formula Hg O. It has a red or orange color. Mercury(II) oxide is a solid at room temperature and pressure. The mineral form montroydite is v ...

, first synthesized by Abu al-Qasim al-Qurtubi al-Majriti (10th century).

* Modern surgery. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936–1013 AD), better known in the west as Albucasis, is regarded as the father of modern surgery and is the most quoted surgeon of all times. Albucasis invented over 200 tools for use in surgery - many still in use today.

* Water and weight driven mechanical clocks, by Spanish Muslim engineers sometime between 900–1200 AD. According to historian Will Durant, a watch like device was invented by Ibn Firnas.Animation

* M-Tecnofantasy - is an animation technique, created by Francisco Macián Blasco, that animators use to trace over motion picture footage, frame by frame, to produce realistic action similar torotoscopy

Rotoscoping is an animation technique that animators use to trace over motion picture footage, frame by frame, to produce realistic action. Originally, animators projected photographed live-action movie images onto a glass panel and traced ...

.

Architecture and construction

*Azulejo

''Azulejo'' (, ; from the Arabic ''al- zillīj'', ) is a form of Spanish and Portuguese painted tin-glazed ceramic tilework. ''Azulejos'' are found on the interior and exterior of churches, palaces, ordinary houses, schools, and nowadays, r ...

* Calatrava style - The futuristic style of architecture invented and designed by world renown Spanish architect, Santiago Calatrava

Santiago Calatrava Valls (born 28 July 1951) is a Spanish architect, structural engineer, sculptor and painter, particularly known for his bridges supported by single leaning pylons, and his railway stations, stadiums, and museums, whose sculp ...

. Examples include the Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències

The City of Arts and Sciences ( vl, Ciutat de les Arts i les Ciències ; es, Ciudad de las Artes y las Ciencias ) is a cultural and architectural complex in the city of Valencia, Spain. It is the most important modern tourist destination in the ...

, in Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, the planned Chicago Spire, Puente del Alamillo

The Alamillo Bridge ( es, Puente del Alamillo) is a structure in Seville, Andalucia (Spain), which spans the Canal de Alfonso XIII, allowing access to La Cartuja, a peninsula located between the canal and the Guadalquivir River. The bridge was ...

, in Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula ...

, and the new World Trade Center Transportation Hub

World Trade Center is a terminal station on the PATH system, within the World Trade Center complex in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City. It is served by the Newark–World Trade Center line at all times, as well as by the H ...

at rebuilt New World Trade Center site

The World Trade Center site, often referred to as "Ground Zero" or "the Pile" immediately after the September 11 attacks, is a 14.6-acre (5.9 ha) area in Lower Manhattan in New York City. The site is bounded by Vesey Street to the north ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

.

* Catalan Gothic

* Catalan Modernisme

''Modernisme'' (, Catalan for "modernism"), also known as Catalan modernism and Catalan art nouveau, is the historiographic denomination given to an art and literature movement associated with the search of a new entitlement of Catalan cultu ...

- a very influential style of architecture used not only in Catalonia but throughout Spain. Its greatest pioneer was the most famous architect Antoni Gaudi Antoni is a Catalan, Polish, and Slovene given name and a surname used in the eastern part of Spain, Poland and Slovenia. As a Catalan given name it is a variant of the male names Anton and Antonio. As a Polish given name it is a variant of the fe ...

and his masterpiece, La Sagrada Familia.

* Hacienda

* Herrerian

The Herrerian style ( es, estilo herreriano or ''arquitectura herreriana'') of architecture was developed in Spain during the last third of the 16th century under the reign of Philip II (1556–1598), and continued in force in the 17th centu ...

* Horseshoe arch

The horseshoe arch (; Spanish: "arco de herradura"), also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is an emblematic arch of Islamic architecture, especially Moorish architecture. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

Hi ...

was first used in Visigothic Spain.

* Isabelline Gothic

The Isabelline style, also called the Isabelline Gothic ( es, Gótico Isabelino), or Castilian late Gothic, was the dominant architectural style of the Crown of Castile during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and ...

* Valencian Gothic

* Valencian Art Nouveau

* Levantine Gothic

* Masia

A masia in Catalan (or es, masía and an, pardina) is a type of rural construction common to the east of Spain: Catalonia, Valencian Community, Aragon, Languedoc and Provence (in the south of France). The estate in which the masia is located is ...

* Mozarabic

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

* Mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

style

* Neo-Mudéjar

Neo-Mudéjar is a type of Moorish Revival architecture practised in the Iberian Peninsula and to a far lesser extent in Ibero-America. This architectural movement emerged as a revival of Mudéjar style. It was an architectural trend of the late ...

* Palloza

A palloza (also known as pallouza or pallaza) is a traditional dwelling of the Serra dos Ancares of northwest Spain.

Structure

A palloza is a traditional thatched house as found in Leonese county of El Bierzo, Serra dos Ancares in Galicia, and ...

* Pazo

* Plateresque

Plateresque, meaning "in the manner of a silversmith" (''plata'' being silver in Spanish), was an artistic movement, especially architectural, developed in Spain and its territories, which appeared between the late Gothic and early Renaissance ...

* Purism

Purism, referring to the arts, was a movement that took place between 1918 and 1925 that influenced French painting and architecture. Purism was led by Amédée Ozenfant and Charles Edouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier). Ozenfant and Le Corbusier f ...

architecture

* Repoblación

* Spanish Colonial Architecture

* Spanish Tile

* Visigothic

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is kno ...

Chemistry

* First process of creating artificial crystals by Ibn Firnas. * Pure alcohol distillation * Moderntoxicology

Toxicology is a scientific discipline, overlapping with biology, chemistry, pharmacology, and medicine, that involves the study of the adverse effects of chemical substances on living organisms and the practice of diagnosing and treating e ...

, by Mateu Orfila Mateu is a Catalan name, meaning Matthew. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Mateu Morral (1880–1906), Spanish anarchist

Surname

* Antonio Mateu Lahoz (born 1977), Spanish football referee

* Jaume Mateu (1382–1452), Valencian ...

(1787–1853).

* Discovery of vanadium (as vanadinite

Vanadinite is a mineral belonging to the apatite group of phosphates, with the chemical formula Pb5( V O4)3 Cl. It is one of the main industrial ores of the metal vanadium and a minor source of lead. A dense, brittle mineral, it is usually f ...

) in 1801 by geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

and chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe t ...

Andrés Manuel del Río (1764–1849)

* Discovery of tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isol ...

by Fausto Elhuyar

Fausto de Elhuyar (11 October 1755 – 6 February 1833) was a Spanish chemist, and the first to isolate tungsten with his brother Juan José Elhuyar in 1783. He was in charge, under a King of Spain commission, of organizing the School of Mines i ...

and his brother Juan José Elhuyar in 1783.

* Discovery of platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

by scientist, soldier and author Antonio de Ulloa

Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giralt, FRS, FRSA, KOS (12 January 1716 – 3 July 1795) was a Spanish naval officer, scientist, and administrator. At the age of nineteen, he joined the French Geodesic Mission to what is now the country o ...

(1716–1795) with Jorge Juan y Santacilia

Jorge Juan y Santacilia (Novelda, Alicante, 5 January 1713 – Madrid, 21 June 1773) was a Spanish mathematician, scientist, naval officer, and mariner. He determined that the Earth is not perfectly spherical but is oblate, i.e. flattened at the ...

(1713–1773).

* Discovery of carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

and pure alcohol by alchemist and physician ''Arnold of Villanova

Arnaldus de Villa Nova (also called Arnau de Vilanova in Catalan, his language, Arnaldus Villanovanus, Arnaud de Ville-Neuve or Arnaldo de Villanueva, c. 1240–1311) was a physician and a religious reformer. He was also thought to be an alchem ...

'' (c. 1235–1311)

Computing and Communications

remote control

In electronics, a remote control (also known as a remote or clicker) is an electronic device used to operate another device from a distance, usually wirelessly. In consumer electronics, a remote control can be used to operate devices such a ...

, by engineer and computer pioneer

This is a list of people who made transformative breakthroughs in the creation, development and imagining of what computers could do.

Pioneers

: ''To arrange the list by date or person (ascending or descending), click that column's small "up-do ...

Leonardo Torres Quevedo (1852–1936)

* Electronic book

An ebook (short for electronic book), also known as an e-book or eBook, is a book publication made available in digital form, consisting of text, images, or both, readable on the flat-panel display of computers or other electronic devices. Alth ...

by teacher, writer and inventor Ángela Ruiz Robles

Ángela Ruiz Robles (March 28, 1895 Villamanín, León - October 27, 1975, Ferrol, A Coruña) was a Spanish teacher, writer, pioneer and inventor of the mechanical precursor to the electronic book, invented 20 years prior to Michael Hart’s P ...

(1895-1975).

Cuisine

* Chocolate caliente (hot chocolate) - the Mesoamericans drank chocolate strait bitter and sometimes flavored with spicy peppers. Spanish conquistadors were not fans of the original mix and instead created their own sweeten hot chocolate by adding sugar from sugar cane. For many years, the Spanish kept their prized chocolate a secret until its expansion into other European courts. * Chorizo *Jamón ibérico

''Jamón ibérico'' (; pt, presunto ibérico ), "Iberian ham" is a variety of ''jamón'' or ''presunto'', a type of cured leg of pork produced in Spain and, to a lesser extent, Portugal.

Description

According to Spain's '' denominación d ...

* Spanish omelette

Spanish omelette or Spanish tortilla is a traditional dish from Spain. Celebrated as a national dish by Spaniards, it is an essential part of the Spanish cuisine. It is an omelette made with eggs and potatoes, optionally including onion. It is o ...

* Jerez

Jerez de la Frontera (), or simply Jerez (), is a Spanish city and municipality in the province of Cádiz in the autonomous community of Andalusia, in southwestern Spain, located midway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Cádiz Mountains. , the c ...

- also known as Sherry

* Paella

Paella (, , , , , ) is a rice dish originally from Valencia. While non-Spaniards commonly view it as Spain's national dish, Spaniards almost unanimously consider it to be a dish from the Valencian region. Valencians, in turn, regard ''paella'' ...

* Spanish cuisine

Spanish cuisine consists of the cooking traditions and practices from Spain. Olive oil (of which Spain is the world's largest producer) is heavily used in Spanish cuisine. It forms the base of many vegetable sauces (known in Spanish as ''sofrit ...

Economics

* Development of the first monetarist theory and the quantitative theory of money byeconomist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this field there are ...

Martín de Azpilcueta (1492–1586), member of the School of Salamanca

The School of Salamanca ( es, Escuela de Salamanca) is the Renaissance of thought in diverse intellectual areas by Spanish theologians, rooted in the intellectual and pedagogical work of Francisco de Vitoria. From the beginning of the 16th cen ...

.

* Precursor of international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

theory by Francisco de Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( – 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known as the School of Sala ...

(c. 1480/86 – 1546), member of the School of Salamanca

The School of Salamanca ( es, Escuela de Salamanca) is the Renaissance of thought in diverse intellectual areas by Spanish theologians, rooted in the intellectual and pedagogical work of Francisco de Vitoria. From the beginning of the 16th cen ...

* First world currency

Fashion

Spain has been a center of fashion since medieval times. Barcelona and Madrid have both been named as fashion capitals of the world, with Barcelona being the fifth most important fashion capital in the world back in 2015. Spain is the home country of the largest fashion retail store and textiles designer in the world, Zara and its parentInditex

Industria de Diseño Textil, S.A. (Inditex; , ; ) is a Spanish multinational clothing company headquartered in Arteixo, Galicia, in Spain. Inditex, the biggest fast fashion group in the world, operates over 7,200 stores in 93 markets worldwide. ...

, making their CEO main shareholder, Amancio Ortega Gaona

Amancio Ortega Gaona (; born 28 March 1936) is a Spanish billionaire businessman. He is the founder and former chairman of Inditex fashion group, best known for its chain of Zara (retailer), Zara and Bershka clothing and accessories shops. As ...

, the second wealthiest man in the world in 2015. Barcelona is the headquarters of another international retail company, Mango.

Inventions:

* Farthingale

A farthingale is one of several structures used under Western European women's clothing in the 16th and 17th centuries to support the skirts in the desired shape and enlarge the lower half of the body. It originated in Spain in the fifteenth c ...

* Spray-on-clothing by Manel Torres

Mathematics and statistics

*Borda Count

The Borda count is a family of positional voting rules which gives each candidate, for each ballot, a number of points corresponding to the number of candidates ranked lower. In the original variant, the lowest-ranked candidate gets 0 points, the ...

- by Ramon Llull, around 1299, centuries before Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

.G. Hägele & F. Pukelsheim (2001). "Llull's writings on electoral systems". Studia Lulliana. 41: 3–38.

* Condorcet criterion

An electoral system satisfies the Condorcet winner criterion () if it always chooses the Condorcet winner when one exists. The candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidatesthat is, a ...

- by Ramon Llull, around 1299, centuries before Nicolas de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

.

* Contributions to the field of Dynamical Systems by Ricardo Pérez-Marco

* Nualart stochastic processes and stochastic analysis (field of probability theory).

* Speculative Arithmetic

* Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

- reforms from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar by Spanish mathematician, Pedro Chacón.

* Geostatistical Analysis of Compositional Data In statistics, compositional data are quantitative descriptions of the parts of some whole, conveying relative information. Mathematically, compositional data is represented by points on a simplex. Measurements involving probabilities, proportions, ...

by Vera Pawlowsky-Glahn

Vera Pawlowsky-Glahn (born September 25, 1951) is a Spanish-German mathematician. From 2000 till 2018, she was a full-time professor at the University of Girona, Spain in the Department of Computer Science, Applied Mathematics, and Statistics. Si ...

and Ricardo A. Olea.

* Group Theory

In abstract algebra, group theory studies the algebraic structures known as group (mathematics), groups.

The concept of a group is central to abstract algebra: other well-known algebraic structures, such as ring (mathematics), rings, field ...

and Lie algebras

In mathematics, a Lie algebra (pronounced ) is a vector space \mathfrak g together with an Binary operation, operation called the Lie bracket, an Alternating multilinear map, alternating bilinear map \mathfrak g \times \mathfrak g \rightarrow ...

works done by Maria Wonenburger

María Josefa Wonenburger Planells ( Montrove, Oleiros, Galicia, July 17, 1927 – A Coruña, June 14, 2014) was a Galician mathematician who did research in the United States and Canada. She is known for her work on group theory. She was the fir ...

(1927–2014).

* Integral geometry by Luís Antoni Santaló Sors

* Modelling and Analysis of Compositional Data In statistics, compositional data are quantitative descriptions of the parts of some whole, conveying relative information. Mathematically, compositional data is represented by points on a simplex. Measurements involving probabilities, proportions, ...

by Vera Pawlowsky-Glahn

Vera Pawlowsky-Glahn (born September 25, 1951) is a Spanish-German mathematician. From 2000 till 2018, she was a full-time professor at the University of Girona, Spain in the Department of Computer Science, Applied Mathematics, and Statistics. Si ...

, Juan José Egozcue, Raimon Tolosana-Delgado

* Nonlinear partial differential equations and their applications by Juan Luis Vázquez Suárez

* Oscillation theory of the obliquity of the ecliptic by Abū Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn Yaḥyā al-Naqqāsh al-Zarqālī, also known as Al-Zarqali or Ibn Zarqala (1029–1087).

* Spherical Trigonometry - work of Abū Abd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī (989–1079 AD). Greatly influenced Western mathematics, including the works of Regiomontanus.

* Tirocinio aritmético by María Andrea Casamayor (1700–1780)

* Works of Enrique Zuazua in applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is the application of mathematical methods by different fields such as physics, engineering, medicine, biology, finance, business, computer science, and industry. Thus, applied mathematics is a combination of mathemati ...

in the fields of partial differential equations, control theory and numerical analysis

Medicine and biology

* Synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA) by

* Synthesis of ribonucleic acid (RNA) by Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

Laureate Severo Ochoa

Severo Ochoa de Albornoz (; 24 September 1905 – 1 November 1993) was a Spanish physician and biochemist, and winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with Arthur Kornberg for their discovery of "the mechanisms in ...

(1905–1993).

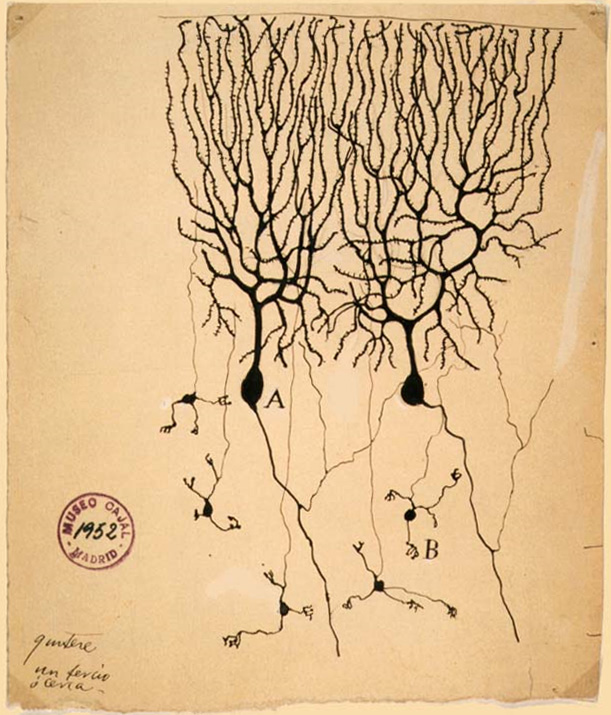

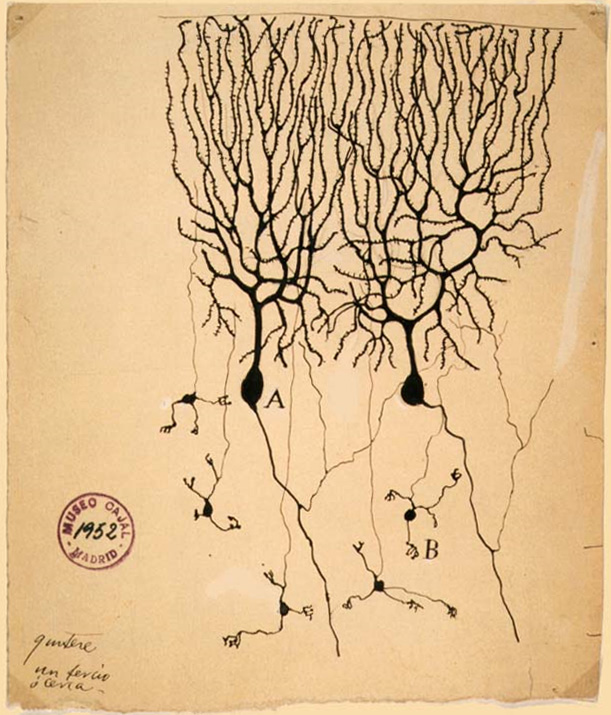

* Neuroscience

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions and disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, developme ...

by Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

Laureate (1906) Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934).

* Discovery of the microglia or ''Hortega cell'' by the neuroscientist

A neuroscientist (or neurobiologist) is a scientist who has specialised knowledge in neuroscience, a branch of biology that deals with the physiology, biochemistry, psychology, anatomy and molecular biology of neurons, neural circuits, and glial ...

Pío del Río Hortega

Pío del Río Hortega (1882 – 1945) was a Spanish neuroscientist who discovered microglia.

Biography

Río Hortega was born in Portillo, Valladolid on 5 May 1882. He studied locally and qualified to practice medicine in 1905. He obtained his do ...

(1882–1945)

* Discovery that the human cell has 46 chromosomes - jointly discovered with a Swedish scientist.

* Discovery that the parasitic agent of Chagas disease, Trypanosoma cruzi

''Trypanosoma cruzi'' is a species of parasitic euglenoids. Among the protozoa, the trypanosomes characteristically bore tissue in another organism and feed on blood (primarily) and also lymph. This behaviour causes disease or the likelihood o ...

, reproduce by cloning - discovered by Francisco J. Ayala

Francisco José Ayala Pereda (born March 12, 1934) is a Spanish-American evolutionary biologist, philosopher, and former Catholic priest who was a longtime faculty member at the University of California, Irvine and University of California, Dav ...

.

* The effect of hormone levels on the mind - crucial to forming a relationship between psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries between ...

and endocrinology

Endocrinology (from '' endocrine'' + '' -ology'') is a branch of biology and medicine dealing with the endocrine system, its diseases, and its specific secretions known as hormones. It is also concerned with the integration of developmental event ...

, by Gregorio Marañón

Gregorio Marañón y Posadillo, OWL (19 May 1887 in Madrid – 27 March 1960 in Madrid) was a Spanish physician, scientist, historian, writer and philosopher. He married Dolores Moya in 1911, and they had four children (Carmen, Belén, María ...

.

* First European description of pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

by scientist, surgeon and humanist Miguel Servet (1511–1553)

* A worldwide used "two-piece" disposable syringe (1978) by Manuel Jalón Corominas (1925–2011)

* Use of Radiology

Radiology ( ) is the medical discipline that uses medical imaging to diagnose diseases and guide their treatment, within the bodies of humans and other animals. It began with radiography (which is why its name has a root referring to radiat ...

and Radiotherapy for diagnostics by Celedonio Calatayud (1880-1931).

* Animal Testing

Animal testing, also known as animal experimentation, animal research, and ''in vivo'' testing, is the use of non-human animals in experiments that seek to control the variables that affect the behavior or biological system under study. This ...

, first recorded use of animals for medical testing was done by Ibn Zuhr, known as Avenzoar, (1094–1162).

* Antiseptics

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

were in used as early as the 10th century in hospitals in Islamic Spain. Special protocols, in Al Andalus, were used to keep hygiene before and after surgery.

*Botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, Spanish botanist, like Ibn al-Baitar, created hundreds of works/catalogs on the various plants in not only Europe but the Middle East, Africa and Asia. In these works many processes for extracting essential oils, drugs as well as their uses can be found.

* The CRISPR System, discovered by Francisco Mojica

Francisco Juan Martínez Mojica (born 5 October 1963) is a Spanish molecular biologist and microbiologist at the University of Alicante in Spain. He is known for his discovery of repetitive, functional DNA sequences in bacteria which he named CR ...

, from the University of Alicante

The University of Alicante ( ca-valencia, Universitat d'Alacant, italic=no, ; es, Universidad de Alicante, italic=no, ; also known by the acronym ''UA'') was established in 1979 on the basis of the Center for University Studies (CEU), which was fo ...

.

* Ectopic pregnancy, first described by Al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

(936–1013 AD).

* Eye glasses

Glasses, also known as eyeglasses or spectacles, are vision eyewear, with lenses (clear or tinted) mounted in a frame that holds them in front of a person's eyes, typically utilizing a bridge over the nose and hinged arms (known as temples ...

, first invented by Ibn Firnas in the 9th century.

* Inheritance of traits first proposed by Abu Al-Zahrawi (936–1013 AD) more than 800 years before Austrian monk, Mendel. Al-Zahrawi was first to record and suggest that hemophilia was an inherited disease.

* Inhalation anesthesia, invented by al-Zahrawi and Ibn Zuhr. Used a sponge soaked with narcotic drugs and placed it on patients face.

* Laryngoscope

Laryngoscopy () is endoscopy of the larynx, a part of the throat. It is a medical procedure that is used to obtain a view, for example, of the vocal folds and the glottis. Laryngoscopy may be performed to facilitate tracheal intubation during ge ...

by singer, music educator, and vocal pedagogue Manuel García (1805–1906).

* Ligatures, described in the work of al-Zahrawi (936–1013 AD), Kitab al-Tasrif, one of the most influential books in early modern medicine. Describes the process of performing a ligature on blood vessels.

* Migraine surgery, first performed by al-Zahrawi (936–1013 AD).

* Modern surgery. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (936–1013 AD), better known in the west as Albucasis, is regarded as the father of modern surgery and is the most quoted surgeon of all times. Albucasis invented over 200 tools for use in surgery - many still in use today.

* Nuubo - Wearable medical technology that measures heart rate, blood pressure, perspiration, body temperature and current location.

* Pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

- various Muslim physicians in Spain were crucial in the development of modern medicine. Pathology, obviously was an important development in medicine. The first correct proposal of the nature of disease was described by al-Zahrawi and Ibn Zuhr.

* Pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (from the obsolete typography ''pharmacopœia'', meaning "drug-making"), in its modern technical sense, is a book containing directions for the identification of compound medicines, and published by ...

(book of medicine). During the 14th century, the physician from Malaga, Ibn Baytar, wrote a pharmacopoeia naming over 1400 different drugs and their uses in medicine. This book was written 200 years before the supposed first pharmacopoeia was written by German scholar in 1542.

* Silver bromide

Silver bromide (AgBr) is a soft, pale-yellow, water-insoluble salt well known (along with other silver halides) for its unusual sensitivity to light. This property has allowed silver halides to become the basis of modern photographic materials. A ...

method.

* Wheelchair

A wheelchair is a chair with wheels, used when walking is difficult or impossible due to illness, injury, problems related to old age, or disability. These can include spinal cord injuries ( paraplegia, hemiplegia, and quadriplegia), cerebr ...

- first European design for the use of the most powerful man in the world at the time, King Phillip II of Spain, who was suffering from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

.

* Yellow Fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

Transmission - Luis Alvarez, born in Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

(then Kingdom of Spain) was first to discover that Yellow Fever was transmitted through mosquitoes ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its le ...

''.

Meteorology

* The barocyclonometer, thenephoscope

A nephoscope is a 19th-century instrument for measuring the altitude, direction, and velocity of clouds, using transit-time measurement. This is different from a nephometer, which is an instrument used in measuring the amount of cloudiness.

De ...

, and the microseismograph by meteorologist José María Algué (1856–1930).

Military

*First amphibious landing of tanks at Alhucemas bay in 1925 and a precursor of Allied amphibious operations in World War II. *'' Destructor'' - The main precursor of the destroyer type of warship, laid down in 1885.Smith, Charles Edgar: ''A short history of naval and marine engineering.'' Babcock & Wilcox, ltd. at the University Press, 1937, page 263 * Training of aggressive dogs for warfare. *Falcata

The falcata is a type of sword typical of pre-Roman Iberia. The falcata was used to great effect for warfare in the ancient Iberian peninsula, and is firmly associated with the southern Iberian tribes, among other ancient peoples of Hispania. ...

swords used by Iberian tribes.F. Quesada SanzGladius hispaniensis: an archaeological view from Iberia

1997 * Gladius Hispanensis (antennae swords) - Swords adopted by the Romans after the second Punic war. The Iberian sword was considered superior to that of the Romans. * Guerrilla warfare developed in Spain during the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian peninsula. *

Miquelet lock

Miquelet lock is a modern term used by collectors and curators for a type of firing mechanism used in muskets and pistols. It is a distinctive form of snaplock, originally as a flint-against-steel ignition form, once prevalent in the Spanish ...

was invented by gunsmiths in Madrid during the late 16th century (circa 1570).

* Molotov cocktail

A Molotov cocktail (among several other names – ''see other names'') is a hand thrown incendiary weapon constructed from a frangible container filled with flammable substances equipped with a fuse (typically a glass bottle filled with fla ...

s were first developed in Spain during the Spanish civil war and were ordered to be used by the Nationalist forces against Soviet T-26

The T-26 tank was a Soviet light tank used during many conflicts of the Interwar period and in World War II. It was a development of the British Vickers 6-Ton tank and was one of the most successful tank designs of the 1930s until its light ...

tanks supporting the Spanish Republic.

* Peral Submarine, design of the first fully operative military submarine by Isaac Peral

Isaac Peral y Caballero (1 June 1851, in Cartagena – 22 May 1895, in Berlin), was a Spanish engineer, naval officer and designer of the Peral Submarine. He joined the Spanish navy in 1866, and developed the first electric-powered submarine whi ...

(1851–1895).

*First professional army in Europe – men were hired and trained in Spain to join the army as their professional job not as some levy or through hiring mercenaries.

*Rapier

A rapier () or is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Impo ...

- Spain was the first European country to use rapiers.

*First use of a rotorcraft

A rotorcraft or rotary-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft with rotary wings or rotor blades, which generate lift by rotating around a vertical mast. Several rotor blades mounted on a single mast are referred to as a rotor. The Internat ...

in combat, during the suppression of the Asturias Rebellion in 1934

*Tercios

A ''tercio'' (; Spanish for " third") was a military unit of the Spanish Army during the reign of the Spanish Habsburgs in the early modern period. The tercios were renowned for the effectiveness of their battlefield formations, forming the el ...

greatly modernized fighting in Europe. It is seen by military historians as one of the great developments of combined arms and tactics for warfare. The Spanish Tercios were undefeated in every war until Battle of Rocroi in 1643 and were greatly feared as an invincible army.

* Toledo steel

Toledo steel, historically known for being unusually hard, is from Toledo, Spain, which has been a traditional sword-making, metal-working center since about the Roman period, and came to the attention of Rome when used by Hannibal in the Punic W ...

- The Iberian region has been known for high quality metal working and sword productions since pre-Roman times. Toledo steel refers to both the high quality steel and that legacy of steel work in the Iberian peninsula from pre-Roman to post-Roman times in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by ...

was said to be the only rival of Toledo steel in the Middle Ages.

Musical Instruments

*Alboka

The Basque ( es, albogue) is a single-reed woodwind instrument consisting of a single reed, two small diameter melody pipes with finger holes and a bell traditionally made from animal horn. Additionally, a reed cap of animal horn is placed arou ...

* Bandurria

* Botet

* Catalan shawm

In music, a Catalan shawm is one of two varieties of shawm, an oboe-like woodwind musical instrument played in Catalonia in northeastern Spain.

Region, types, and uses

The types of shawm commonly used in Catalonia are the tible (, Catalan for "t ...

* Classical guitar

* Chácaras

* the univerese

* Dulzaina

The dulzaina () or dolçaina (/) is a Spanish double reed instrument in the oboe family. It has a conical shape and is the equivalent of the Breton bombarde. It is often replaced by an oboe or a double reeded clarinet as seen in Armenian an ...

* Fiscorn

* Flabiol

The flabiol () is a Catalan woodwind musical instrument of the family known as '' fipple flutes''. It is one of the 12 instruments of the cobla. The flabiol measures about 25 centimeters in length and has five or six holes on its front face a ...

* Gaita Asturiana

* Gaita de boto

* Gaita gastoreña

The gaita gastoreña is a type of hornpipe native to El Gastor, a region of Andalucia, Spain. It consists of a simple reed, a wooden tube in its upper part, and a resonating bell of horn in its lower part. Such instruments are only found outsi ...

* Gaita de saco

* Gaita sanabresa

* Galician gaita

* Gralla

* Guitarra de canya

* Kirikoketa

The kirikoketa ( or ) is a specialized Basque music wooden device akin to the txalaparta and closely related to working activities. It is classified as an idiophone (a percussion instrument). It has lately caught on with cultural circles from the ...

* Nunun

* Palmas

* Psalterium

* Reclam de xeremies

* Sac de gemecs

* Tambori

The tambori ( ca, tamborí ) is a percussion instrument of about 10 centimetres diameter, a small shallow cylinder formed of metal or wood with a drumhead of skin. Its usual function is to accompany the playing of the flabiol in a cobla band, beat ...

* Timple

* Trikiti

The trikiti ( standard Basque, pronounced ) trikitixa ( dialectal Basque, pronounced ), or eskusoinu txiki ("little hand-sound", pronounced )) is a two-row Basque diatonic button accordion with right-hand rows keyed a fifth apart and twelve un ...

* Trompa de Ribagorza

* Txalaparta

The txalaparta ( or ) is a specialized Basque music device of wood or stone. In some regions of the Basque Country, (with ) means "racket", while in others (in Navarre) has been attested as meaning the trot of the horse, a sense closely relate ...

* Txistu

The txistu () is a kind of fipple flute that became a symbol for the Basque folk revival. The name may stem from the general Basque word ''ziztu'' "to whistle" with palatalisation of the ''z'' (cf ''zalaparta'' > ''txalaparta''). This three-hol ...

* Violí de bufa

* Xeremia

The ''xeremia'' (, plural ''xeremies'') is a type of bagpipe native to the island of Majorca (''Mallorca'').* It consists of a bag made of skin (or modern synthetic materials), known as a ''sac'' or ''sarró'' which retains the air, a blowpipe (' ...

* Xirula

The xirula (, spelled ''chiroula'' in French, also pronounced ''txirula'', ''(t)xülüla'' in Zuberoan Basque; Gascon: ''flabuta''; French: ''galoubet'') is a small three holed woodwind instrument or flute usually made of wood akin to the Basque ...

Sociology, Philosophy and Politics

* Anarcho-syndicalism * Averroism - the school of philosophy founded by Al-Andalus philosopherAverroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psy ...

. Averroes in one of the most quoted men of the medieval era and has greatly influenced Western Europe.

* Balance of Powers

* Borda Count

The Borda count is a family of positional voting rules which gives each candidate, for each ballot, a number of points corresponding to the number of candidates ranked lower. In the original variant, the lowest-ranked candidate gets 0 points, the ...

- by Ramon Llull, around 1299, centuries before Jean-Charles de Borda

Jean-Charles, chevalier de Borda (4 May 1733 – 19 February 1799) was a French mathematician, physicist, and Navy officer.

Biography

Borda was born in the city of Dax to Jean‐Antoine de Borda and Jeanne‐Marie Thérèse de Lacroix.

In 17 ...

G. Hägele & F. Pukelsheim (2001). "Llull's writings on electoral systems". Studia Lulliana. 41: 3–38

* Condorcet criterion

An electoral system satisfies the Condorcet winner criterion () if it always chooses the Condorcet winner when one exists. The candidate who wins a majority of the vote in every head-to-head election against each of the other candidatesthat is, a ...

- by Ramon Llull, around 1299, centuries before Nicolas de Condorcet

Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis of Condorcet (; 17 September 1743 – 29 March 1794), known as Nicolas de Condorcet, was a French philosopher and mathematician. His ideas, including support for a liberal economy, free and equal pu ...

* Expropriative anarchism

* International Law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

- According to the main argument agreed at Salamance, the common good of the world is of a category superior to the good of each state. This meant that relations between states ought to pass from being justified by force to being justified by law and justice. Hence calling for international law.

* Justification of war - argued greatly in the School of Salamanca. The main argument was given that war is one of the worst evils suffered by mankind, the adherents of the School reasoned that it ought to be resorted to only when it was necessary in order to prevent an even greater evil. A diplomatic agreement is preferable, even for the more powerful party, before a war is started. Even war for the conversion of pagans and infidels was considered unjust at the school of Salamanca.

* Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Tora ...

* Razon Historica

* Raciovitalismo

* Rights of People - Francisco de Vitoria is the first western European to argue for the rights of man and is considered the father of modern rights of people theory. His most famous work is ''Ius Gentium'' (Latin for ''The Rights of People'')

* Stoicism - Some of the most important stoic philosophical works are by Iberian born or descendent philosophers including the works of Seneca the younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

, born in Cordoba, as well as the stoic masterpiece, Meditations

''Meditations'' () is a series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from AD 161 to 180, recording his private notes to himself and ideas on Stoic philosophy.

Marcus Aurelius wrote the 12 books of the ''Meditations'' in Koine ...

, by Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

, born in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

but whose family originate in Ucubi, Spain (small town close to Cordoba).

* Second Scholasticism

Second scholasticism (or late scholasticism) is the period of revival of scholastic system of philosophy and theology, in the 16th and 17th centuries. The scientific culture of second scholasticism surpassed its medieval source ( Scholasticism) ...

- Francisco Suarez is considered the most important European scholastic after Thomas Aquinas.

* School of Salamanca Movement - greatly intertwined with second scholasticism, but it was the rise in philosophical works on politics, ethics, religion, society and human rights. As we know, our modern concept of human rights, equality and liberty originate in the enlightenment revolutions, especially in France and US, however, about 300–200 years before the enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, the great scholars of the University of Salamanca were writing and discussing the same ideas. The ideas of international law, balance of powers, civil law, order, and just war were all discussed and debated by these Spanish scholars. Francisco Suarez is the most famous Salamancan scholar of this era. Is considered the most important European scholastic after Thomas Aquinas.

Transportation

*Autogyro

An autogyro (from Greek and , "self-turning"), also known as a ''gyroplane'', is a type of rotorcraft that uses an unpowered rotor in free autorotation to develop lift. Forward thrust is provided independently, by an engine-driven propeller. Whi ...

by Juan de la Cierva, pioneer of rotary flight, direct precursor of the helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

.

* The steam powered water pump by Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont, who created and patented a steam-powered water pump for draining mines, an early precursor to the steam engine.

* First machine powered submarine by Narcís Monturiol

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol (; Narciso Monturiol Estarriol, in Spanish, 28 September 1819 – 6 September 1885) was a Spanish inventor, artist and engineer born in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain. He was the inventor of the first air-independent an ...

(1818–1885)

Physics and Astronomy

* Equatorium * Theoretical work on Gravity by Juan Bautista Villalpando (born 1552 in Córdoba, died 22 May 1608). He may be the father of gravitational theory and influence Newton, who indeed had copies of Bautista's work on gravity, geometry and architecture. Baustista produced 21 original propositions on the center of gravity and the line of direction. * First full-pressuredspace suit

A space suit or spacesuit is a garment worn to keep a human alive in the harsh environment of outer space, vacuum and temperature extremes. Space suits are often worn inside spacecraft as a safety precaution in case of loss of cabin pressure, ...

, called the escafandra estratonáutica, designed and made by Emilio Herrera Linares, in 1935. The Russians then used a model of Herrera's suit when first flying into space of which the Americans would then later adopt when creating their own space program.

* First planetarium by Ibn Firnas.

* Spherical Earth Theory by Ibn Hazm (994-1064 AD).

* Tables of Toledo

The ''Toledan Tables'', or ''Tables of Toledo'', were astronomical tables which were used to predict the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets relative to the fixed stars. They were a collection of mathematic tables that describe different aspe ...

* Viscoelastic gravity layer

* Water and weight driven mechanical clocks, by Spanish Muslim engineers sometime between 900–1200 AD. According to historian Will Durant, a watch like device was invented by Ibn Firnas.

* Magnetic wormhole

A wormhole ( Einstein-Rosen bridge) is a hypothetical structure connecting disparate points in spacetime, and is based on a special solution of the Einstein field equations.

A wormhole can be visualized as a tunnel with two ends at separate p ...

- first ever manmade wormhole created at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona by Spanish physicist Jordi Prat-Camps. The magnetic wormhole makes the magnetic field invisible.

Miscellaneous

stapler

A stapler is a mechanical device that joins pages of paper or similar material by driving a thin metal staple through the sheets and folding the ends. Staplers are widely used in government, business, offices, work places, homes and schools.

...

, designed and created in the Basque country of Spain for French King, Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

, in the 18th century. The staples had engraved on them the royal emblem.

* First cigarette. The mesoamericans, like the Mayans

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical reg ...

and Aztecs smoked tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

by using different leaves as rolling paper, the Spanish were the first to manufacture the grandfather of the modern day cigarette. When tobacco first made it onto Spanish shores in the 17th century, maize wrappers were used to roll and then fine paper.

* The oldest folding/pocket knife

A pocketknife is a knife with one or more blades that fold into the handle. They are also known as jackknives (jack-knife), folding knives, or may be referred to as a penknife, though a penknife may also be a specific kind of pocketknife. A typ ...

have been found during the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostl ...

(pre-Roman times)in Spain. The title is contested with folding knives found in Hallstatt culture region in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

from around the same time.

* Foosball

Table football, also known as foosball, table soccer, futbolito in Mexico, Taca Taca in Chile and Metegol in Argentina is a table-top game that is loosely based on association football. The aim of the game is to move the ball into the opponen ...

. The first patent for table football belonged to Spaniard, Alejandro Finisterre

Alejandro Finisterre or Alexandre de Fisterra (born Alexandre Campos Ramírez; 6 May 1919 – 9 February 2007) is known as the inventor of ''futbolín'', a Spanish variant of table football (aka foosball). He was also a poet, publisher and anarchi ...

, though he credits his friend, Francisco Javier Altuna, with the invention.

* Glass mirrors, used in Islamic Spain as early as 11th century – 200 years prior to the Venetians.

See also

* List of Spanish inventors and discoverers * Science and technology in SpainReferences

{{DEFAULTSORT:Spanish inventions and discoveries * Inventions and discoveries Lists of inventions or discoveries