List of Kings of Rome on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Roman Kingdom (also referred to as the Roman monarchy, or the regal period of ancient Rome) was the earliest period of

ImageSize = width:800 height:75

PlotArea = width:700 height:50 left:65 bottom:20

AlignBars = justify

Colors =

id:time value:rgb(0.7,0.7,1) #

id:period value:rgb(1,0.7,0.5) #

id:age value:rgb(0.95,0.85,0.5) #

id:era value:rgb(1,0.85,0.5) #

id:eon value:rgb(1,0.85,0.7) #

id:filler value:gray(0.8) # background bar

id:black value:black

Period = from:-753 till:-509

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:50 start:-753

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:5 start:-753

PlotData =

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:10 mark:(line,black) width:15 shift:(0,-5)

bar:Rulers color:era

from:-753 till:-716 text:

:::''Dates follow

Son of the

Son of the  Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as

After Romulus died, there was an

After Romulus died, there was an

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

The seventh and final king of Rome was

The seventh and final king of Rome was

In order to replace the leadership of the kings, a new office was created with the title of

In order to replace the leadership of the kings, a new office was created with the title of

Roman history

The history of Rome includes the history of the city of Rome as well as the civilisation of ancient Rome. Roman history has been influential on the modern world, especially in the history of the Catholic Church, and Roman law has influenced m ...

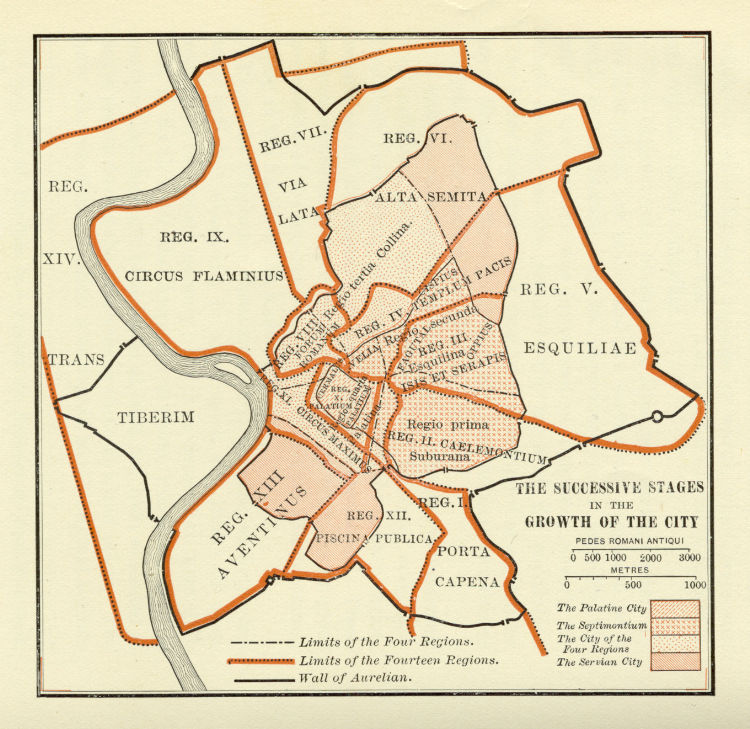

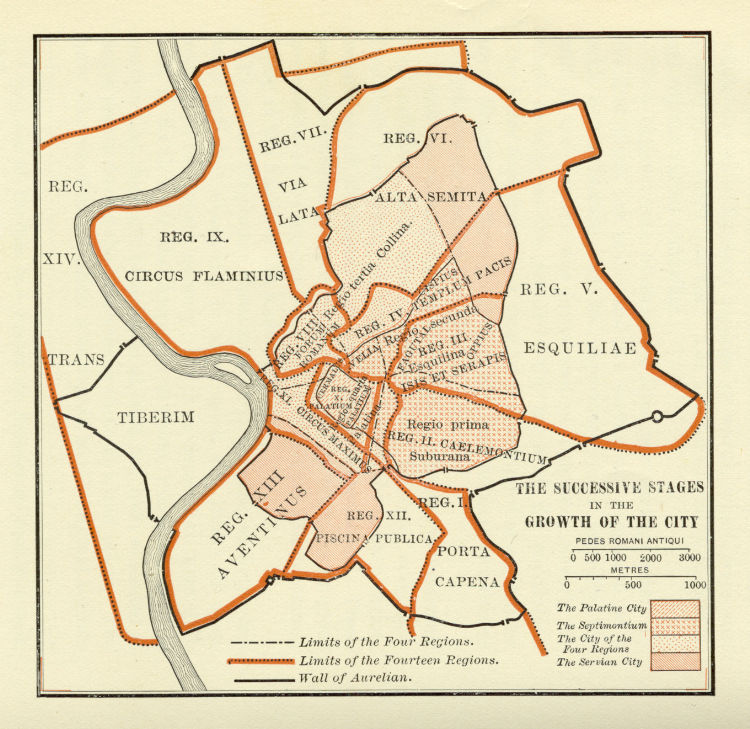

when the city and its territory were ruled by kings. According to oral accounts, the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding 753 BC, with settlements around the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

along the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

in central Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic 509 BC.

Little is certain about the kingdom's history as no records and few inscriptions from the time of the kings survive. The accounts of this period written during the Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

and the Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

are thought largely to be based on oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and Culture, cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Traditio ...

.

Origin

The site of the founding of the Roman Kingdom (and eventualRepublic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

and Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

) had a ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

where one could cross the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

in central Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

and hills surrounding it provided easily defensible positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. Each of these features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional version of Roman history, which has come down to us principally through Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

(64 or 59 BC – AD 12 or 17), Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

(46–120), and Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary styl ...

( 60 BC – after 7 BC), recounts that a series of seven kings ruled the settlement in Rome's first centuries. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

(116 BC – 27 BC) and Fabius Pictor ( 270 – 200 BC), allows 243 years for their combined reigns, an average of almost 35 years. Since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr

Barthold Georg Niebuhr (27 August 1776 – 2 January 1831) was a Danish–German statesman, banker, and historian who became Germany's leading historian of Ancient Rome and a founding father of modern scholarly historiography. By 1810 Niebuhr wa ...

, modern scholarship has generally discounted this schema. The Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

destroyed many of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia

The Battle of the Allia was a battle fought between the Senones – a Gallic tribe led by Brennus, who had invaded Northern Italy – and the Roman Republic. The battle was fought at the confluence of the Tiber and Allia rivers, 11 Roman ...

in 390 BC (according to Varro; according to Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

, the battle occurred in 387/6), and what remained eventually fell prey to time or to theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom surviving, all accounts of the Roman kings must be carefully questioned.

Monarchy

The kings (excludingRomulus

Romulus () was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of these ...

, who, according to legend, held office by virtue of being the city's founder), were all elected by the people of Rome to serve for life, with none of the kings relying on military force to gain or keep the throne.

The insignia of the kings of Rome were twelve lictor

A lictor (possibly from la, ligare, "to bind") was a Roman civil servant who was an attendant and bodyguard to a magistrate who held ''imperium''. Lictors are documented since the Roman Kingdom, and may have originated with the Etruscans.

Origi ...

s (attendants or servants) wielding the symbolic fasces

Fasces ( ; ; a '' plurale tantum'', from the Latin word '' fascis'', meaning "bundle"; it, fascio littorio) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, sometimes including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian sym ...

bearing axes, the right to sit upon a curule seat

A curule seat is a design of a (usually) foldable and transportable chair noted for its uses in Ancient Rome and Europe through to the 20th century. Its status in early Rome as a symbol of political or military power carried over to other civiliza ...

, the purple ''toga picta'', red shoes, and a white diadem

A diadem is a type of crown, specifically an ornamental headband worn by monarchs and others as a badge of royalty.

Overview

The word derives from the Greek διάδημα ''diádēma'', "band" or "fillet", from διαδέω ''diadéō'', " ...

around the head. Of all these insignia, the most important was the purple ''toga picta''.

Chief Executive

The king was invested with supreme military, executive, and judicial authority through the use ofimperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

, formally granted to the king by the Curiate Assembly

The Curiate Assembly (''comitia curiata'') was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome w ...

with the passing of the '' Lex curiata de imperio'' at the beginning of each king's reign. The imperium of the king was held for life and protected him from ever being brought to trial for his actions. As the king was the sole owner of imperium in Rome at the time, he possessed ultimate executive power

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems b ...

and unchecked military authority as the commander-in-chief of all of the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period o ...

s. Also, the laws that kept citizens safe from magistrates' misuse of imperium did not exist during the monarchical period.

Another power of the king was the power to either appoint or nominate all officials to offices. The king would appoint a ''tribunus celerum'' to serve as both the tribune of the Ramnes tribe in Rome and as the commander of the king's personal bodyguard, the ''celeres

__NoToC__

The ''celeres'' () were the bodyguard of the Kings of Rome. Traditionally established by Romulus, the legendary founder and first King of Rome, the celeres comprised three hundred men, ten chosen by each of the curiae.Livy, i. 15. Th ...

''. The king was required to appoint the tribune upon entering office and the tribune left office upon the king's death. The tribune was second in rank to the king and also possessed the power to convene the Curiate Assembly and lay legislation before it.

Another officer appointed by the king was the ''praefectus urbi

The ''praefectus urbanus'', also called ''praefectus urbi'' or urban prefect in English, was prefect of the city of Rome, and later also of Constantinople. The office originated under the Roman kings, continued during the Republic and Empire, a ...

'', who acted as the warden of the city. When the king was absent from the city, the prefect held all of the king's powers and abilities, even to the point of being bestowed with imperium while inside the city.

The king even received the right to be the only person to appoint patricians

The patricians (from la, patricius, Greek: πατρίκιος) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after ...

to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

.

Chief Priest

What is known for certain is that the king alone possessed the right to theaugury

Augury is the practice from ancient Roman religion of interpreting omens from the observed behavior of birds. When the individual, known as the augur, interpreted these signs, it is referred to as "taking the auspices". "Auspices" (Latin ''aus ...

on behalf of Rome as its chief augur

An augur was a priest and official in the classical Roman world. His main role was the practice of augury, the interpretation of the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds. Determinations were based upon whether they were flying ...

, and no public business could be performed without the will of the gods made known through auspices. The people knew the king as a mediator between them and the gods (cf. Latin ''pontifex'', "bridge-builder", in this sense, between men and the gods) and thus viewed the king with religious awe. This made the king the head of the national religion and its chief executive. Having the power to control the Roman calendar

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. The term often includes the Julian calendar established by the reforms of the dictator Julius Caesar and emperor Augustus in the late 1stcenturyBC and some ...

, he conducted all religious ceremonies and appointed lower religious offices and officers. It is said that Romulus himself instituted the augurs and was believed to have been the best augur of all. Likewise, King Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius (; 753–672 BC; reigned 715–672 BC) was the legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus after a one-year interregnum. He was of Sabine origin, and many of Rome's most important religious and political institutions ar ...

instituted the pontiff

A pontiff (from Latin ''pontifex'') was, in Roman antiquity, a member of the most illustrious of the colleges of priests of the Roman religion, the College of Pontiffs."Pontifex". "Oxford English Dictionary", March 2007 The term "pontiff" was l ...

s and through them developed the foundations of the religious dogma of Rome.

Chief Legislator

Under the kings, the Senate and Curiate Assembly had very little power and authority. They were not independent since they lacked the right to meet together and discuss questions of state at their own will. They could be called together only by the king and could discuss only the matters that the king laid before them. While the Curiate Assembly had the power to pass laws that had been submitted by the king, the Senate was effectively an honorary council. It could advise the king on his action but by no means could prevent him from acting. The only thing that the king could not do without the approval of the Senate and the Curiate Assembly was to declare war against a foreign nation.Chief Judge

The king's imperium both granted him military powers and qualified him to pronounce legal judgment in all cases as the chief justice of Rome. Though he could assign pontiffs to act as minor judges in some cases, he had supreme authority in all cases brought before him, both civil and criminal. This made the king supreme in times of both war and peace. While some writers believed there was no appeal from the king's decisions, others believed that a proposal for appeal could be brought before the king by any patrician during a meeting of theCuriate Assembly

The Curiate Assembly (''comitia curiata'') was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome w ...

.

To assist the king, a council advised him during all trials, but this council had no power to control his decisions. Also, two criminal detectives (Quaestores Parricidi) were appointed by him as well as a two-man criminal court (''Duumviri Perduellionis''), which oversaw cases of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

. According to Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I He is commonly known ...

, the seventh and final king of Rome, judged capital criminal cases without the advice of counsellors, thereby creating fear amongst those who might think to oppose him.

Election of the kings

Whenever a king died, Rome entered a period of ''interregnum''. Supreme power of the state would devolve to the Senate, which was responsible for finding a new king. The Senate would assemble and appoint one of its own members—theinterrex

The interrex (plural interreges) was literally a ruler "between kings" (Latin ''inter reges'') during the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic. He was in effect a short-term regent.

History

The office of ''interrex'' was supposedly created follow ...

—to serve for a period of five days with the sole purpose of nominating the next king of Rome. If no king were nominated at the end of five days, with the Senate's consent the interrex would appoint another Senator to succeed him for another five-day term. This process would continue until a new king was elected. Once the interrex found a suitable nominee to the kingship, he would bring the nominee before the Senate and the Senate would review him. If the Senate passed the nominee, the interrex would convene the Curiate Assembly and preside over it during the election of the King.

Once the nominee was proposed to the Curiate Assembly, the people of Rome could either accept or reject him. If accepted, the king-elect did not immediately enter office. Two other acts still had to take place before he was invested with the full regal authority and power.

First, it was necessary to obtain the divine will of the gods respecting his appointment by means of the auspices, since the king would serve as high priest of Rome. This ceremony was performed by an augur, who conducted the king-elect to the citadel, where he was placed on a stone seat as the people waited below. If found worthy of the kingship, the augur announced that the gods had given favourable tokens, thus confirming the king's priestly character.

The second act which had to be performed was the conferral of the imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from '' auctoritas'' and '' potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic a ...

upon the king. The Curiate Assembly's previous vote only determined who was to be king, and had not by that act bestowed the necessary power of the king upon him. Accordingly, the king himself proposed to the Curiate Assembly a law granting him imperium, and the Curiate Assembly by voting in favor of the law would grant it.

In theory, the people of Rome elected their leader, but the Senate had most of the control over the process.

Senate

According to legend, Romulus established the Senate after he founded Rome by personally selecting the most noble men (wealthy men with legitimate wives and children) to serve as a council for the city. As such, the Senate was the King's advisory council as theCouncil of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

. The Senate was composed of 300 Senators, with 100 Senators representing each of the three ancient tribes of Rome: the Ramnes (Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

), Tities (Sabines

The Sabines (; lat, Sabini; it, Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines di ...

), and Luceres (Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

). Within each tribe, a Senator was selected from each of the tribe's ten curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

e. The king had the sole authority to appoint the Senators, but this selection was done in accordance with ancient custom.

Under the monarchy, the Senate possessed very little power and authority as the king held most of the political power of the state and could exercise those powers without the Senate's consent. The chief function of the Senate was to serve as the king's council and be his legislative coordinator. Once legislation proposed by the king passed the Curiate Assembly, the Senate could either veto it or accept it as law. The king was, by custom, to seek the advice of the Senate on major issues. However, it was left to him to decide what issues, if any, were brought before them and he was free to accept or reject their advice as he saw fit. Only the king possessed the power to convene the Senate, except during the interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

, during which the Senate possessed the authority to convene itself.Military

Kings of Rome

;''Years BC''Romulus

Romulus () was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of these ...

from:-716 till:-673 text: Numa

Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''NUMA1'' gene.

Interactions

Nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 has been shown to interact with PIM1, Band 4.1, GPSM2

G-protein-signaling modulator 2, also ca ...

from:-673 till:-642 text: Tullus

from:-642 till:-616 text: Ancus

from:-616 till:-579 text: Priscus

Priscus of Panium (; el, Πρίσκος; 410s AD/420s AD-after 472 AD) was a 5th-century Eastern Roman diplomat and Greek historian and rhetorician (or sophist)...: "For information about Attila, his court and the organization of life genera ...

from:-579 till:-535 text: Servius

from:-535 till:-509 text: Superbus

bar: color:filler

from: -753 till: -673 text:Early

from: -673 till: -616 text:Middle

from: -616 till: -509 text:Late

Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

's chronology of reign-lengths. Consult particular article for details of each king.''

Romulus

Son of the

Son of the Vestal Virgin

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals ( la, Vestālēs, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before puberty ...

Rhea Silvia

Rhea (or Rea) Silvia (), also known as Ilia (as well as other names) was the mythical mother of the twins Romulus and Remus, who founded the city of Rome. Her story is told in the first book of ''Ab Urbe Condita Libri'' of Livy and in Cassius D ...

, ostensibly by the god Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

, the legendary Romulus

Romulus () was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of these ...

was Rome's founder and first king. After he and his twin brother Remus had deposed King Amulius of Alba and reinstated the king's brother and their grandfather Numitor

In Roman mythology, King Numitor () of Alba Longa, was the maternal grandfather of Rome's founder and first king, Romulus, and his twin brother Remus. He was the son of Procas, descendant of Aeneas the Trojan, and father of the twins' mother, ...

to the throne, they decided to build a city in the area where they had been abandoned as infants. After killing Remus in a dispute, Romulus began building the city on the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

. His work began with fortifications. He permitted men of all classes to come to Rome as citizens, including slaves and freemen without distinction. He is credited with establishing the city's religious, legal and political institutions. The kingdom was established by unanimous acclaim with him at the helm when Romulus called the citizenry to a council for the purposes of determining their government.

Romulus established the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

as an advisory council with the appointment of 100 of the most noble men in the community. These men he called ''patres'' (from ''pater'', father, head), and their descendants became the patricians

The patricians (from la, patricius, Greek: πατρίκιος) were originally a group of ruling class families in ancient Rome. The distinction was highly significant in the Roman Kingdom, and the early Republic, but its relevance waned after ...

. To project command, he surrounded himself with attendants, in particular the twelve lictors. He created three divisions of horsemen (''equites''), called ''centuries'': ''Ramnes'' (Romans), ''Tities'' (after the Sabine king) and ''Luceres'' (Etruscans). He also divided the populace into 30 ''curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

e'', named after 30 of the Sabine women who had intervened to end the war between Romulus and Tatius. The ''curiae'' formed the voting units in the popular assemblies

A popular assembly (or people's assembly) is a gathering called to address issues of importance to participants. Assemblies tend to be freely open to participation and operate by direct democracy. Some assemblies are of people from a location ...

(''Comitia Curiata'').

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as

Romulus was behind one of the most notorious acts in Roman history, the incident commonly known as the rape of the Sabine women

The Rape of the Sabine Women ( ), also known as the Abduction of the Sabine Women or the Kidnapping of the Sabine Women, was an incident in Roman mythology in which the men of Rome committed a mass abduction of young women from the other citi ...

. To provide his citizens with wives, Romulus invited the neighbouring tribes to a festival in Rome where the Romans committed a mass abduction of young women from among the attendees. The account vary from 30 to 683 women taken, a significant number for a population of 3,000 Latins (and presumably for the Sabines as well). War broke out when Romulus refused to return the captives. After the Sabines made three unsuccessful attempts to invade the hill settlements of Rome, the women themselves intervened during the Battle of the Lacus Curtius

In Roman mythology, the Battle of the Lacus Curtius was the final battle in the war between the Roman Kingdom and the Sabines following Rome's mass abduction of Sabine women to take as brides. It took place during the reign of Romulus, near ...

to end the war. The two peoples were united in a joint kingdom, with Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius

According to the Roman foundation myth, Titus Tatius was the king of the Sabines from Cures and joint-ruler of the Kingdom of Rome for several years.

During the reign of Romulus, the first king of Rome, Tatius declared war on Rome in resp ...

sharing the throne. In addition to the war with the Sabines, Romulus waged war with the Fidenates and Veientes and others.

He reigned for thirty-seven years.Plutarch ''Life of Romulus'' 29.7 According to the legend, Romulus vanished at age fifty-four while reviewing his troops on the Campus Martius. He was reported to have been taken up to Mt. Olympus in a whirlwind and made a god. After initial acceptance by the public, rumours and suspicions of foul play by the patricians began to grow. In particular, some thought that members of the nobility had murdered him, dismembered his body, and buried the pieces on their land. These were set aside after an esteemed nobleman testified that Romulus had come to him in a vision and told him that he was the god Quirinus

In Roman mythology and religion, Quirinus ( , ) is an early god of the Roman state. In Augustan Rome, ''Quirinus'' was also an epithet of Janus, as ''Janus Quirinus''.

Name

Attestations

The name of god Quirinus is recorded across Roman so ...

. He became, not only one of the three major gods of Rome, but the very likeness of the city itself.

A replica of Romulus' hut was maintained in the centre of Rome until the end of the Roman Empire.

Numa Pompilius

After Romulus died, there was an

After Romulus died, there was an interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

for one year, during which ten men chosen from the senate governed Rome as successive '' interreges''. Under popular pressure, the Senate finally chose the Sabine Numa Pompilius

Numa Pompilius (; 753–672 BC; reigned 715–672 BC) was the legendary second king of Rome, succeeding Romulus after a one-year interregnum. He was of Sabine origin, and many of Rome's most important religious and political institutions ar ...

to succeed Romulus, on account of his reputation for justice and piety. The choice was accepted by the Curiate Assembly.

Numa's reign was marked by peace and religious reform. He constructed a new temple to Janus

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus ( ; la, Ianvs ) is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Jan ...

and, after establishing peace with Rome's neighbours, closed the doors of the temple to indicate a state of peace. They remained closed for the rest of his reign.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''Ab urbe condita

''Ab urbe condita'' ( 'from the founding of the City'), or ''anno urbis conditae'' (; 'in the year since the city's founding'), abbreviated as AUC or AVC, expresses a date in years since 753 BC, the traditional founding of Rome. It is an ex ...

'', 1:19 He established the Vestal Virgins

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals ( la, Vestālēs, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before pubert ...

at Rome, as well as the Salii

In ancient Roman religion, the Salii ( , ) were the "leaping priests" (from the verb ''saliō'' "leap, jump") of Mars supposed to have been introduced by King Numa Pompilius. They were twelve patrician youths, dressed as archaic warriors: an emb ...

, and the flamines for Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Roman god of war. Mars is a terrestrial planet with a thin at ...

and Quirinus

In Roman mythology and religion, Quirinus ( , ) is an early god of the Roman state. In Augustan Rome, ''Quirinus'' was also an epithet of Janus, as ''Janus Quirinus''.

Name

Attestations

The name of god Quirinus is recorded across Roman so ...

. He also established the office and duties of Pontifex Maximus. Numa reigned for 43 years. He reformed the Roman calendar

The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. The term often includes the Julian calendar established by the reforms of the dictator Julius Caesar and emperor Augustus in the late 1stcenturyBC and some ...

by adjusting it for the solar and lunar year, as well as by adding the months of January and February to bring the total number of months to twelve.

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius

Tullus Hostilius (r. 672–640 BC) was the legendary third king of Rome. He succeeded Numa Pompilius and was succeeded by Ancus Marcius. Unlike his predecessor, Tullus was known as a warlike king who according to the Roman Historian Livy, bel ...

was as warlike as Romulus had been, completely unlike Numa as he lacked any respect for the gods. Tullus waged war against Alba Longa

Alba Longa (occasionally written Albalonga in Italian sources) was an ancient Latin city in Central Italy, 12 miles (19 km) southeast of Rome, in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. Founder and head of the Latin League, it wa ...

, Fidenae and Veii and the Sabines

The Sabines (; lat, Sabini; it, Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines di ...

. During Tullus's reign, the city of Alba Longa was completely destroyed and Tullus integrated its population into Rome. Tullus is attributed with constructing a new home for the Senate, the Curia Hostilia

The Curia Hostilia was one of the original senate houses or "curiae" of the Roman Republic. It was believed to have begun as a temple where the warring tribes laid down their arms during the reign of Romulus (r. c. 771–717 BC). During the early ...

, which survived for 562 years after his death.

According to Livy, Tullus neglected the worship of the gods until, towards the end of his reign, he fell ill and became superstitious. However, when Tullus called upon Jupiter and begged assistance, Jupiter responded with a bolt of lightning that burned the king and his house to ashes. His reign lasted for 32 years.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The wor ...

'', I

Ancus Marcius

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson,

Following the mysterious death of Tullus, the Romans elected a peaceful and religious king in his place, Numa's grandson, Ancus Marcius

Ancus Marcius was the legendary fourth king of Rome, who traditionally reigned 24 years. Upon the death of the previous king, Tullus Hostilius, the Roman Senate appointed an interrex, who in turn called a session of the assembly of the people wh ...

. Much like his grandfather, Ancus did little to expand the borders of Rome and only fought wars to defend the territory. He also built Rome's first prison on the Capitoline Hill

The Capitolium or Capitoline Hill ( ; it, Campidoglio ; la, Mons Capitolinus ), between the Forum and the Campus Martius, is one of the Seven Hills of Rome.

The hill was earlier known as ''Mons Saturnius'', dedicated to the god Saturn. ...

.

Ancus further fortified the Janiculum

The Janiculum (; it, Gianicolo ), occasionally the Janiculan Hill, is a hill in western Rome, Italy. Although it is the second-tallest hill (the tallest being Monte Mario) in the contemporary city of Rome, the Janiculum does not figure among t ...

Hill on the western bank, and built the first bridge across the Tiber River

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by the Ri ...

. He also founded the port of Ostia on the Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

and established Rome's first salt works, as well as the city's first aqueduct. Rome grew, as Ancus used diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. ...

to peacefully unite smaller surrounding cities into alliance with Rome. Thus, he completed the conquest of the Latins and relocated them to the Aventine Hill

The Aventine Hill (; la, Collis Aventinus; it, Aventino ) is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth '' rione'', or ward, of Rome.

Location and boundaries

The Aventine Hill is the so ...

, thus forming the plebeian

In ancient Rome, the plebeians (also called plebs) were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words " commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins ...

class of Romans.

He died a natural death, like his grandfather, after 25 years as king, marking the end of Rome's Latin-Sabine kings.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The wor ...

'', I

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, or Tarquin the Elder, was the legendary fifth king of Rome and first of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned for thirty-eight years.Livy, ''ab urbe condita libri'', I Tarquinius expanded Roman power through military conq ...

was the fifth king of Rome and the first of Etruscan birth. After immigrating to Rome, he gained favor with Ancus, who later adopted him as son. Upon ascending the throne, he waged wars against the Sabines and Etruscans, doubling the size of Rome and bringing great treasures to the city. To accommodate the influx of population, the Aventine and Caelian hill

The Caelian Hill (; la, Collis Caelius; it, Celio ) is one of the famous seven hills of Rome.

Geography

The Caelian Hill is a sort of long promontory about long, to wide, and tall in the park near the Temple of Claudius. The hill ov ...

s were populated.

One of his first reforms was to add 100 new members to the Senate from the conquered Etruscan tribes, bringing the total number of senators to 200. He used the treasures Rome had acquired from the conquests to build great monuments for Rome. Among these were Rome's great sewer systems, the Cloaca Maxima

The Cloaca Maxima ( lat, Cloāca Maxima, lit. ''Greatest Sewer'') was one of the world's earliest sewage systems. Its name derives from Cloacina, a Roman goddess. Built during either the Roman Kingdom or early Roman Republic, it was constructed ...

, which he used to drain the swamp-like area between the Seven Hills of Rome. In its place, he began construction on the Roman Forum

The Roman Forum, also known by its Latin name Forum Romanum ( it, Foro Romano), is a rectangular forum ( plaza) surrounded by the ruins of several important ancient government buildings at the center of the city of Rome. Citizens of the ancie ...

. He also founded the Roman games.

Priscus initiated great building projects, including the city's first bridge, the Pons Sublicius. The most famous is the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and l ...

, a giant stadium for chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&n ...

races. After that, he started the building of the temple-fortress to the god Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. However, before it was completed, he was killed by a son of Ancus Marcius, after 38 years as king.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The wor ...

'', I His reign is best remembered for introducing the Roman symbols of military and civil offices, and the Roman triumph

The Roman triumph (') was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or in some historical tra ...

, being the first Roman to celebrate one.

Servius Tullius

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law

Priscus was succeeded by his son-in-law Servius Tullius

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned from 578 to 535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, ...

, Rome's second king of Etruscan birth, and the son of a slave. Like his father-in-law, Servius fought successful wars against the Etruscans. He used the booty to build the first wall all around the Seven Hills of Rome, the pomerium

The ''pomerium'' or ''pomoerium'' was a religious boundary around the city of Rome and cities controlled by Rome. In legal terms, Rome existed only within its ''pomerium''; everything beyond it was simply territory ('' ager'') belonging to Rome. ...

. He also reorganized the army.

Servius Tullius instituted a new constitution, further developing the citizen classes. He instituted Rome's first census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses inc ...

which divided the population into five economic classes, and formed the Centuriate Assembly

The Centuriate Assembly (Latin: ''comitia centuriata'') of the Roman Republic was one of the three voting assemblies in the Roman constitution. It was named the Centuriate Assembly as it originally divided Roman citizens into groups of one hundre ...

. He used the census to divide the population into four urban tribes based on location, thus establishing the Tribal Assembly

The Tribal Assembly (''comitia populi tributa'') was an assembly consisting of all Roman citizens convened by tribes (''tribus'').

In the Roman Republic, citizens did not elect legislative representatives. Instead, they voted themselves on legis ...

. He also oversaw the construction of the temple to Diana on the Aventine Hill

The Aventine Hill (; la, Collis Aventinus; it, Aventino ) is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth '' rione'', or ward, of Rome.

Location and boundaries

The Aventine Hill is the so ...

.

Servius’ reforms made a big change in Roman life: voting rights based on socio-economic status, favouring elites. However, over time, Servius increasingly favoured the poor in order to gain support from plebs, often at the expense of patricians. After a 44-year reign,Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The wor ...

'', I Servius was killed in a conspiracy by his daughter Tullia and her husband Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I He is commonly known ...

.

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

The seventh and final king of Rome was

The seventh and final king of Rome was Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (died 495 BC) was the legendary seventh and final king of Rome, reigning 25 years until the popular uprising that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I He is commonly known ...

. He was the son of Priscus and the son-in-law of Servius whom he and his wife had killed.

Tarquinius waged a number of wars against Rome's neighbours, including against the Volsci

The Volsci (, , ) were an Italic tribe, well known in the history of the first century of the Roman Republic. At the time they inhabited the partly hilly, partly marshy district of the south of Latium, bounded by the Aurunci and Samnites on the ...

, Gabii

Gabii was an ancient city of Latium, located due east of Rome along the Via Praenestina, which was in early times known as the ''Via Gabina''.

It was on the south-eastern perimeter of an extinct volcanic crater lake, approximately circular ...

and the Rutuli

The Rutuli or Rutulians were an ancient people in Italy. The Rutuli were located in a territory whose capital was the ancient town of Ardea, located about 35 km southeast of Rome.

Thought to have been descended from the Umbri and the Pelas ...

. He also secured Rome's position as head of the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

cities. He also engaged in a series of public works, notably the completion of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus ( la, Aedes Iovis Optimi Maximi Capitolini; it, Tempio di Giove Ottimo Massimo; ) was the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline ...

, and works on the Cloaca Maxima

The Cloaca Maxima ( lat, Cloāca Maxima, lit. ''Greatest Sewer'') was one of the world's earliest sewage systems. Its name derives from Cloacina, a Roman goddess. Built during either the Roman Kingdom or early Roman Republic, it was constructed ...

and the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, it was the first and l ...

. However, Tarquin's reign is remembered for his use of violence and intimidation to control Rome, and his disrespect for Roman custom and the Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

.

Tensions came to a head when the king's son, Sextus Tarquinius

Sextus Tarquinius was the third and youngest son of the last king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, according to Livy, but by Dionysius of Halicarnassus he was the oldest of the three.Roman Antiquities Book 4.69 According to Roman tradition, ...

, raped Lucretia

According to Roman tradition, Lucretia ( /luːˈkriːʃə/ ''loo-KREE-shə'', Classical Latin: ʊˈkreːtɪ.a died c. 510 BC), anglicized as Lucrece, was a noblewoman in ancient Rome, whose rape by Sextus Tarquinius (Tarquin) and subseq ...

, wife and daughter to powerful Roman nobles. Lucretia told her relatives about the attack, and committed suicide to avoid the dishonour of the episode. Four men, led by Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus ( 6th century BC) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic, and traditionally one of its first consuls in 509 BC. He was reputedly responsible for the expulsion of his uncle the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after ...

, and including Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, Publius Valerius Poplicola

Publius Valerius Poplicola or Publicola (died 503 BC) was one of four Roman aristocrats who led the overthrow of the monarchy, and became a Roman consul, the colleague of Lucius Junius Brutus in 509 BC, traditionally considered the first year of ...

, and Spurius Lucretius Tricipitinus incited a revolution that deposed and expelled Tarquinius and his family from Rome in 509 BC.

Tarquin was viewed so negatively that the word for king, '' rex'', held a negative connotation in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

language until the fall of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

.

Brutus and Collatinus became Rome's first consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

, marking the beginning of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

. This new government would survive for the next 500 years until the rise of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

and Caesar Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, and would cover a period during which Rome's authority and area of control extended to cover great areas of Europe, North Africa, and the West Asia.Matyszak 2003, pp. 43-45. He ruled 25 years.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''ab urbe condita libri

The work called ( en, From the Founding of the City), sometimes referred to as (''Books from the Founding of the City''), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by Livy, a Roman historian. The wor ...

'', I

Public offices after the monarchy

In order to replace the leadership of the kings, a new office was created with the title of

In order to replace the leadership of the kings, a new office was created with the title of consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

. Initially, the consuls possessed all of the king's powers in the form of two men, elected for a one-year term, who could veto each other's actions. Later, the consuls’ powers were broken down further by adding other magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

that each held a small portion of the king's original powers. First among these was the praetor

Praetor ( , ), also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected '' magistratus'' (magistrate), assigned to discharge vari ...

, which removed the consuls’ judicial authority from them. Next came the censor, which stripped from the consuls the power to conduct the census.

The Romans instituted the idea of a dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

. A dictator would have complete authority over civil and military matters within the Roman ''imperium''. Since he was not legally responsible for his actions as a dictator, he was unquestionable. However, the power of the dictator was so absolute that Ancient Romans were hesitant in electing one, reserving this decision only to times of severe emergencies. Although this seems similar to the roles of a king, dictators of Rome were limited to serving a maximum six-month term limit. Contrary to the modern notion of a dictator as a usurper, Roman dictators were freely chosen, usually from the ranks of consuls, during turbulent periods when one-man rule proved more efficient.

The king's religious powers were given to two new offices: the Rex Sacrorum

In ancient Roman religion, the ''rex sacrorum'' ("king of the sacred things", also sometimes ''rex sacrificulus'') was a senatorial priesthood reserved for patricians. Although in the historical era, the '' pontifex maximus'' was the head of R ...

and the Pontifex Maximus. The Rex Sacrorum was the ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' highest religious official for the Republic. His sole task was to make the annual sacrifice to Jupiter, a privilege that had been previously reserved for the king. The Pontifex Maximus, however, was the ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' highest religious official and held most of the king's religious authority. He had the power to appoint all vestal virgins

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals ( la, Vestālēs, singular ) were priestesses of Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals were unlike any other public priesthood. They were chosen before pubert ...

, flamens, pontiffs, and even the Rex Sacrorum himself. By the beginning of the 1st century BC, the Rex Sacrorum was all but forgotten, and the Pontifex Maximus given almost complete religious authority over the Roman religion.

Notes and references

Sources

*Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, ''Ab Urbe Condita

''Ab urbe condita'' ( 'from the founding of the City'), or ''anno urbis conditae'' (; 'in the year since the city's founding'), abbreviated as AUC or AVC, expresses a date in years since 753 BC, the traditional founding of Rome. It is an ex ...

''.

*

*

Further reading

* * * {{Authority control Ancient Italian historyKings

Kings or King's may refer to:

*Monarchs: The sovereign heads of states and/or nations, with the male being kings

*One of several works known as the "Book of Kings":

**The Books of Kings part of the Bible, divided into two parts

**The ''Shahnameh'' ...

Rome Kings

8th-century BC establishments in Italy

750s BC

States and territories established in the 8th century BC

States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC

6th-century BC disestablishments

509 BC

1st-millennium BC disestablishments in Italy

Latial culture

Former countries

Former monarchies of Europe