Leon M. Lederman on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

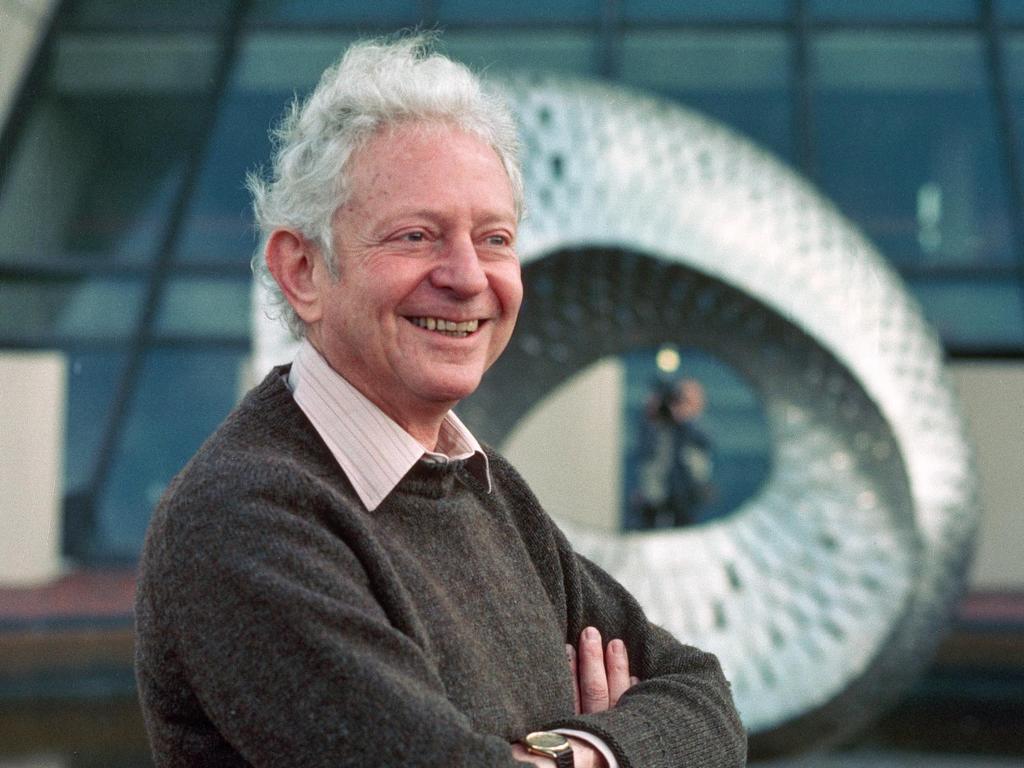

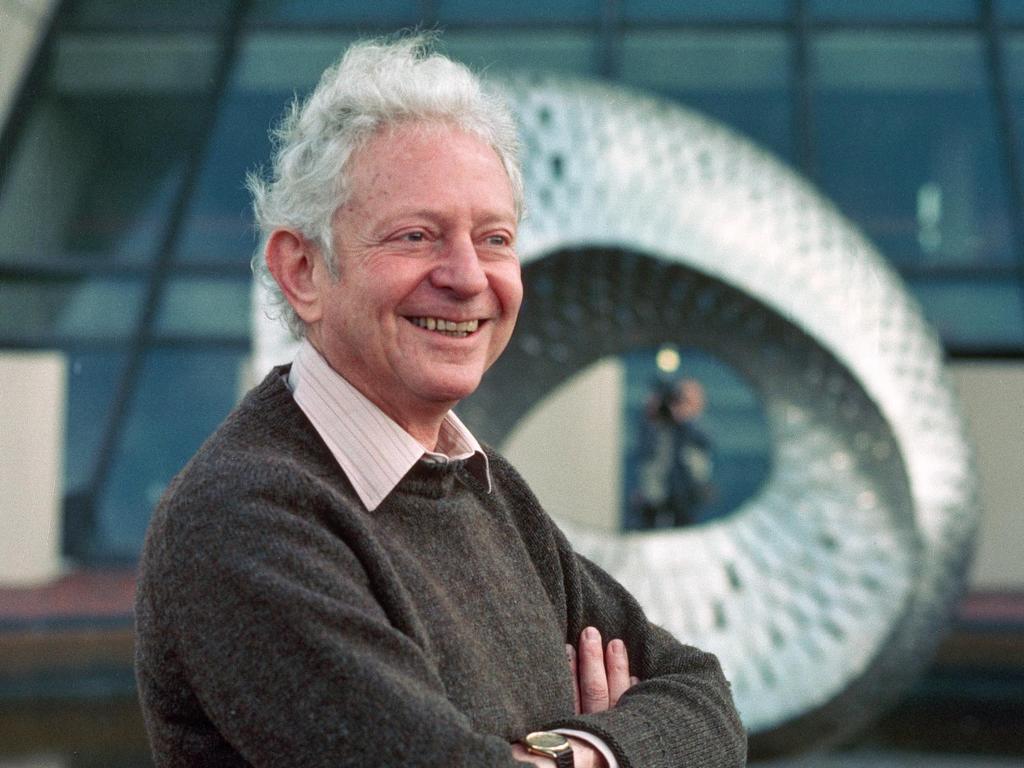

Leon Max Lederman (July 15, 1922 – October 3, 2018) was an American experimental physicist who received the

Lederman's best friend during his college years,

Lederman's best friend during his college years,

Education, Politics, Einstein and Charm

''The Science Network'' interview with Leon Lederman

*

Video Interview with Lederman from the Nobel Foundation

* ttp://ed.fnal.gov/lml/Leon_life.html ''Story of Leon'' by Leon Lederman

Honeywell – Nobel Interactive Studio

1976 Cresson Medal recipient

from The

Honoring Leon Lederman

at APS April 2019 * *

at

Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

in 1988, along with Melvin Schwartz and Jack Steinberger

Jack Steinberger (born Hans Jakob Steinberger; May 25, 1921December 12, 2020) was a German-born American physicist noted for his work with neutrinos, the subatomic particles considered to be elementary constituents of matter. He was a recipient ...

, for research on neutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is a fermion (an elementary particle with spin of ) that interacts only via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass ...

s. He also received the Wolf Prize in Physics

The Wolf Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Wolf Foundation in Israel. It is one of the six Wolf Prizes established by the Foundation and awarded since 1978; the others are in Agriculture, Chemistry, Mathematics, Medicine and Arts ...

in 1982, along with Martin Lewis Perl

Martin Lewis Perl (June 24, 1927 – September 30, 2014) was an American chemical engineer and physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1995 for his discovery of the tau lepton.

Life and career

Perl was born in New York City, New York. Hi ...

, for research on quark

A quark () is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei. All commonly ...

s and lepton

In particle physics, a lepton is an elementary particle of half-integer spin (spin ) that does not undergo strong interactions. Two main classes of leptons exist: charged leptons (also known as the electron-like leptons or muons), and neutr ...

s. Lederman was director emeritus of Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been operat ...

(Fermilab) in Batavia, Illinois

Batavia () is a city mainly in Kane County and partly in DuPage County in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located in the Chicago metropolitan area, it was founded in 1833 and is the oldest city in Kane County. Per the 2020 census, the populati ...

. He founded the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy

The Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy, or IMSA, is a three-year residential public secondary education institution in Aurora, Illinois, United States, with an enrollment of approximately 650 students.

Enrollment is generally offered to inc ...

, in Aurora, Illinois

Aurora is a city in the Chicago metropolitan area located partially in DuPage, Kane, Kendall, and Will counties in the U.S. state of Illinois. Located primarily in DuPage and Kane counties, it is the second most populous city in Illinois, a ...

in 1986, where he was Resident Scholar Emeritus from 2012 until his death in 2018.

An accomplished scientific writer, he became known for his 1993 book '' The God Particle'' establishing the popularity of the term for the Higgs boson

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field,

one of the fields in particle physics theory. In the Stan ...

.

Early life

Lederman was born in New York City, New York, to Morris and Minna (Rosenberg) Lederman. His parents were Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants fromKyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

and Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

. Lederman graduated from James Monroe High School in the South Bronx

The South Bronx is an area of the New York City borough of the Bronx. The area comprises neighborhoods in the southern part of the Bronx, such as Concourse, Mott Haven, Melrose, and Port Morris.

In the early 1900s, the South Bronx was orig ...

, and received his bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to si ...

from the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

in 1943.

Lederman enlisted in the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, intending to become a physicist after his service. Following his discharge in 1946, he enrolled at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's graduate school, receiving his Ph.D. in 1951.

Academic career

Lederman became a faculty member at Columbia University, and he was promoted to full professor in 1958 asEugene Higgins

Eugene Higgins (1860 – 1948) was the rich heir to a carpet-making business, known as a ''bon vivant'', sportsman, and philanthropist. A bachelor, when he died in 1948, his estate went to establish the Higgins Trust, at that time, the eleventh la ...

Professor of Physics. In 1960, on leave from Columbia, he spent time at CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research, known as CERN (; ; ), is an intergovernmental organization that operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. Established in 1954, it is based in a northwestern suburb of Gen ...

in Geneva as a Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

Fellow. He took an extended leave of absence from Columbia in 1979 to become director of Fermilab. Resigning from Columbia (and retiring from Fermilab) in 1989, he then taught briefly at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

. He then moved to the physics department of the Illinois Institute of Technology

Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the merger of the Armour Institute and Lewis Institute in 1940. The university has prog ...

, where he served as the Pritzker Professor of Science. In 1992, Lederman served as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is an American international non-profit organization with the stated goals of promoting cooperation among scientists, defending scientific freedom, encouraging scientific respons ...

.

Lederman, rare for a Nobel Prize winning professor, took it upon himself to teach physics to non-physics majors at The University of Chicago.

Lederman served as President of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and at the time of his death was Chair Emeritus. He also served on the board of trustees for Science Service, now known as Society for Science & the Public, from 1989 to 1992, and was a member of the JASON defense advisory group. Lederman was also one of the main proponents of the " Physics First" movement. Also known as "Right-side Up Science" and "Biology Last," this movement seeks to rearrange the current high school science curriculum so that physics precedes chemistry and biology.

Lederman was an early supporter of Science Debate 2008 Science Debate 2008, currently '' ScienceDebate.org'', was the beginning of a grassroots campaign to call for a public debate in which the candidates for the U.S. presidential election discuss issues relating to the environment, health and medicine, ...

, an initiative to get the then-candidates for president, Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

and John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American politician and United States Navy officer who served as a United States senator from Arizona from 1987 until his death in 2018. He previously served two te ...

, to debate the nation's top science policy challenges. In October 2010, Lederman participated in the USA Science and Engineering Festival's Lunch with a Laureate program where middle and high school students engaged in an informal conversation with a Nobel Prize-winning scientist over a brown-bag lunch. Lederman was also a member of the USA Science and Engineering Festival's advisory board.

Academic work

In 1956, Lederman worked onparity

Parity may refer to:

* Parity (computing)

** Parity bit in computing, sets the parity of data for the purpose of error detection

** Parity flag in computing, indicates if the number of set bits is odd or even in the binary representation of the ...

violation in weak interactions. R. L. Garwin, Leon Lederman, and R. Weinrich modified an existing cyclotron experiment, and they immediately verified the parity violation

In physics, a parity transformation (also called parity inversion) is the flip in the sign of ''one'' spatial coordinate. In three dimensions, it can also refer to the simultaneous flip in the sign of all three spatial coordinates (a point ref ...

. They delayed publication of their results until after Wu's group was ready, and the two papers appeared back-to-back in the same physics journal. Among his achievements are the discovery of the muon neutrino in 1962 and the bottom quark

The bottom quark or b quark, also known as the beauty quark, is a third-generation heavy quark with a charge of − ''e''.

All quarks are described in a similar way by electroweak and quantum chromodynamics, but the bottom quark has exce ...

in 1977. These helped establish his reputation as among the top particle physicists.

In 1977, a group of physicists, the E288 experiment team, led by Lederman announced that a particle with a mass of about 6.0 GeV was being produced by the Fermilab particle accelerator. After taking further data, the group discovered that this particle did not actually exist, and the "discovery" was named "Oops-Leon

Oops-Leon is the name given by particle physicists to what was thought to be a new subatomic particle "discovered" at Fermilab in 1976. The E288 experiment team, a group of physicists led by Leon Lederman who worked on the E288 particle detector, ...

" as a pun on the original name and Lederman's first name.

As the director of Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been oper ...

, Lederman was a prominent supporter of the Superconducting Super Collider project, which was endorsed around 1983, and was a major proponent and advocate throughout its lifetime. Also at Fermilab, he oversaw the construction of the Tevatron

The Tevatron was a circular particle accelerator (active until 2011) in the United States, at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (also known as ''Fermilab''), east of Batavia, Illinois, and is the second highest energy particle collider ...

, for decades the world's highest-energy particle collider. Lederman later wrote his 1993 popular science

''Popular Science'' (also known as ''PopSci'') is an American digital magazine carrying popular science content, which refers to articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. ''Popular Science'' has won over 58 awards, incl ...

book '' The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question?'' – which sought to promote awareness of the significance of such a project – in the context of the project's last years and the changing political climate of the 1990s. The increasingly moribund project was finally shelved that same year after some $2 billion of expenditures. In ''The God Particle'' he wrote, "The history of atomism is one of reductionism – the effort to reduce all the operations of nature to a small number of laws governing a small number of primordial objects" while stressing the importance of the Higgs boson

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field,

one of the fields in particle physics theory. In the Stan ...

.

In 1988, Lederman received the Nobel Prize for Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

along with Melvin Schwartz and Jack Steinberger

Jack Steinberger (born Hans Jakob Steinberger; May 25, 1921December 12, 2020) was a German-born American physicist noted for his work with neutrinos, the subatomic particles considered to be elementary constituents of matter. He was a recipient ...

"for the neutrino beam method and the demonstration of the doublet structure of the leptons through the discovery of the muon neutrino". Lederman also received the National Medal of Science (1965), the Elliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848. The ...

for Physics (1976), the Wolf Prize for Physics (1982) and the Enrico Fermi Award (1992). In 1995, he received the Chicago History Museum

Chicago History Museum is the museum of the Chicago Historical Society (CHS). The CHS was founded in 1856 to study and interpret Chicago's history. The museum has been located in Lincoln Park since the 1930s at 1601 North Clark Street at the int ...

"Making History Award" for Distinction in Science Medicine and Technology.

Personal life

Lederman's best friend during his college years,

Lederman's best friend during his college years, Martin J. Klein

Martin Jesse Klein (June 25, 1924 – March 28, 2009), usually cited as M. J. Klein, was a science historian of 19th and 20th century physics.

Biography

Klein was born in the Bronx, New York City. He was an only child and both his parents we ...

, convinced him of "the splendors of physics during a long evening over many beers". He was known for his sense of humor in the physics community. On August 26, 2008, Lederman was video-recorded by a science focused organization called ScienCentral, on the street in a major U.S. city, answering questions from passersby. He answered questions such as "What is the strong force?" and "What happened before the Big Bang?".

Lederman was an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

. He had three children with his first wife, Florence Gordon, and toward the end of his life lived with his second wife, Ellen (Carr), in Driggs, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

.

Lederman began to suffer from memory loss in 2011 and, after struggling with medical bills, he had to sell his Nobel medal for $765,000 to cover the costs in 2015. He died of complications from dementia on October 3, 2018, at a care facility in Rexburg, Idaho at the age of 96.

Honors and awards

* Election to theNational Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nat ...

, 1965.

* National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

, 1965.

* Election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, a ...

, 1970.

* Elliott Cresson Prize of the Franklin Institute, 1976.

* Wolf Prize in Physics

The Wolf Prize in Physics is awarded once a year by the Wolf Foundation in Israel. It is one of the six Wolf Prizes established by the Foundation and awarded since 1978; the others are in Agriculture, Chemistry, Mathematics, Medicine and Arts ...

, 1982.

* Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

, 1982.

* Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

, 1988.

* Election to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, 1989.

* Enrico Fermi Prize

The Enrico Fermi Prize, first awarded in 2001, is given by the Italian Physical Society (Società Italiana di Fisica). It is a yearly award of €30,000 honoring one or more Members of the Society who have "particularly honoured physics with thei ...

of the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United States ...

, 1992.

* Appointment as a Tetelman Fellow at Jonathan Edwards College

Jonathan Edwards College (informally JE) is a residential college at Yale University. It is named for theologian and minister Jonathan Edwards, a 1720 graduate of Yale College. JE's residential quadrangle was the first to be completed in Yale's ...

, 1994.

* Doctor of Humane Letters, DePaul University

DePaul University is a private, Catholic research university in Chicago, Illinois. Founded by the Vincentians in 1898, the university takes its name from the 17th-century French priest Saint Vincent de Paul. In 1998, it became the largest Ca ...

, 1995.

* Ordem Nacional do Merito Cientifico (Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

), 1995.

* ''In Praise of Reason'' from the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), formerly known as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), is a program within the US non-profit organization Center for Inquiry (CFI), which seeks to "pro ...

(CSICOP), 1996.

* Medallion, Division of Particles and Fields, Mexican Physical Society, 1999.

* AAAS Philip Hauge Abelson Prize The AAAS Philip Hauge Abelson Prize is awarded by The American Association for the Advancement of Science for public servants, recognized for sustained exceptional contributions to advancing science or scientists, whose career has been distinguished ...

, 2000

* Vannevar Bush Prize, 2012.

* Asteroid 85185 Lederman, discovered by Eric Walter Elst

Eric Walter Elst (30 November 1936 – 2 January 2022) was a Belgian astronomer at the Royal Observatory of Belgium in Uccle and a prolific discoverer of asteroids. The Minor Planet Center ranks him among the top 10 discoverers of minor planet ...

at La Silla Observatory

La Silla Observatory is an astronomical observatory in Chile with three telescopes built and operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Several other telescopes are located at the site and are partly maintained by ESO. The observatory is ...

in 1991, was named in his honor. The official was published by the Minor Planet Center

The Minor Planet Center (MPC) is the official body for observing and reporting on minor planets under the auspices of the International Astronomical Union (IAU). Founded in 1947, it operates at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

Function

T ...

on 27 January 2013 ().

Publications

* ''The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question?'' by Leon M. Lederman, Dick Teresi () * ''From Quarks to the Cosmos'' by Leon Lederman and David N. Schramm () * ''Portraits of Great American Scientists'' by Leon M. Lederman, et al. () * ''Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe'' by Leon M. Lederman andChristopher T. Hill

Christopher T. Hill (born June 19, 1951) is an American theoretical physicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory who did undergraduate work in physics at M.I.T. (B.S., M.S., 1972), and graduate work at Caltech (Ph.D., 1977, Murray Gel ...

()

* "What We'll Find Inside the Atom" by Leon Lederman, an essay he wrote for ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'', 15 September 2008

* ''Quantum Physics for Poets'' by Leon M. Lederman and Christopher T. Hill ()

* ''Beyond the God Particle'' by Leon M. Lederman and Christopher T. Hill()

See also

*List of Jewish Nobel laureates

Nobel Prizes have been awarded to over 900 individuals, of whom at least 20% were Jews.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

The number of Jews receiving Nobel prizes has been the subject of some attention.*

*

*"Jews rank high among winners of Nobel, but why ...

References and notes

External links

*Education, Politics, Einstein and Charm

''The Science Network'' interview with Leon Lederman

*

Video Interview with Lederman from the Nobel Foundation

* ttp://ed.fnal.gov/lml/Leon_life.html ''Story of Leon'' by Leon Lederman

Honeywell – Nobel Interactive Studio

1976 Cresson Medal recipient

from The

Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

Honoring Leon Lederman

at APS April 2019 * *

at

Fermilab

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab), located just outside Batavia, Illinois, near Chicago, is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory specializing in high-energy particle physics. Since 2007, Fermilab has been oper ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lederman, Leon

1922 births

2018 deaths

Jewish American atheists

American Nobel laureates

American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

20th-century American physicists

American skeptics

City College of New York alumni

Columbia University alumni

Columbia University faculty

Enrico Fermi Award recipients

Experimental physicists

Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Illinois Institute of Technology faculty

Jewish American scientists

Jewish physicists

Members of JASON (advisory group)

Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

Military personnel from New York City

National Medal of Science laureates

Nobel laureates in Physics

Particle physicists

People associated with CERN

Recipients of the Great Cross of the National Order of Scientific Merit (Brazil)

Scientists from New York City

University of Chicago faculty

Wolf Prize in Physics laureates

Fellows of the American Physical Society

People associated with Fermilab

United States Army personnel of World War II

James Monroe High School (New York City) alumni