Lee DeForest on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lee de Forest (August 26, 1873 – June 30, 1961) was an American

Reflecting his pioneering work, de Forest has sometimes been credited as the "Father of Radio", an honorific which he adopted as the title of his 1950 autobiography. In the late 1800s he became convinced there was a great future in radiotelegraphic communication (then known as " wireless telegraphy"), but Italian

Reflecting his pioneering work, de Forest has sometimes been credited as the "Father of Radio", an honorific which he adopted as the title of his 1950 autobiography. In the late 1800s he became convinced there was a great future in radiotelegraphic communication (then known as " wireless telegraphy"), but Italian

Despite this setback, de Forest remained in the New York City area, in order to raise interest in his ideas and capital to replace the small working companies that had been formed to promote his work thus far. In January 1902 he met a promoter, Abraham White, who would become de Forest's main sponsor for the next five years. White envisioned bold and expansive plans that enticed the inventor—however, he was also dishonest and much of the new enterprise would be built on wild exaggeration and stock fraud. To back de Forest's efforts, White incorporated the American DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company, with himself as the company's president, and de Forest the Scientific Director. The company claimed as its goal the development of "world-wide wireless".

The original "responder" receiver (also known as the "goo anti-coherer") proved to be too crude to be commercialized, and de Forest struggled to develop a non-infringing device for receiving radio signals. In 1903,

Despite this setback, de Forest remained in the New York City area, in order to raise interest in his ideas and capital to replace the small working companies that had been formed to promote his work thus far. In January 1902 he met a promoter, Abraham White, who would become de Forest's main sponsor for the next five years. White envisioned bold and expansive plans that enticed the inventor—however, he was also dishonest and much of the new enterprise would be built on wild exaggeration and stock fraud. To back de Forest's efforts, White incorporated the American DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company, with himself as the company's president, and de Forest the Scientific Director. The company claimed as its goal the development of "world-wide wireless".

The original "responder" receiver (also known as the "goo anti-coherer") proved to be too crude to be commercialized, and de Forest struggled to develop a non-infringing device for receiving radio signals. In 1903,

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition,

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition,

De Forest also used the arc-transmitter to conduct some of the earliest experimental entertainment radio broadcasts.

De Forest also used the arc-transmitter to conduct some of the earliest experimental entertainment radio broadcasts.

In late 1906, de Forest made a breakthrough when he reconfigured the control electrode, moving it from outside the tube envelope to a position inside the tube between the

In late 1906, de Forest made a breakthrough when he reconfigured the control electrode, moving it from outside the tube envelope to a position inside the tube between the

In May 1910, the Radio Telephone Company and its subsidiaries were reorganized as the North American Wireless Corporation, but financial difficulties meant that the company's activities had nearly come to a halt. De Forest moved to San Francisco, California, and in early 1911 took a research job at the Federal Telegraph Company, which produced long-range radiotelegraph systems using high-powered

In May 1910, the Radio Telephone Company and its subsidiaries were reorganized as the North American Wireless Corporation, but financial difficulties meant that the company's activities had nearly come to a halt. De Forest moved to San Francisco, California, and in early 1911 took a research job at the Federal Telegraph Company, which produced long-range radiotelegraph systems using high-powered

The Radio Telephone Company began selling "Oscillion" power tubes to amateurs, suitable for radio transmissions. The company wanted to keep a tight hold on the tube business, and originally maintained a policy that retailers had to require their customers to return a worn-out tube before they could get a replacement. This style of business encouraged others to make and sell unlicensed vacuum tubes which did not impose a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded in 1915 by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco, whose Audio Tron tubes cost less but were of equal or higher quality. The de Forest company sued Audio Tron Sales, eventually settling out of court.

In April 1917, the company's remaining commercial radio patent rights were sold to AT&T's Western Electric subsidiary for $250,000. During World War I, the Radio Telephone Company prospered from sales of radio equipment to the military. However, it also became known for the poor quality of its vacuum tubes, especially compared to those produced by major industrial manufacturers such as General Electric and Western Electric.

The Radio Telephone Company began selling "Oscillion" power tubes to amateurs, suitable for radio transmissions. The company wanted to keep a tight hold on the tube business, and originally maintained a policy that retailers had to require their customers to return a worn-out tube before they could get a replacement. This style of business encouraged others to make and sell unlicensed vacuum tubes which did not impose a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded in 1915 by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco, whose Audio Tron tubes cost less but were of equal or higher quality. The de Forest company sued Audio Tron Sales, eventually settling out of court.

In April 1917, the company's remaining commercial radio patent rights were sold to AT&T's Western Electric subsidiary for $250,000. During World War I, the Radio Telephone Company prospered from sales of radio equipment to the military. However, it also became known for the poor quality of its vacuum tubes, especially compared to those produced by major industrial manufacturers such as General Electric and Western Electric.

In the summer of 1915, the company received an Experimental license for station 2XG, located at its Highbridge laboratory. In late 1916, de Forest renewed the entertainment broadcasts he had suspended in 1910, now using the superior capabilities of vacuum-tube equipment. 2XG's debut program aired on October 26, 1916, as part of an arrangement with the

In the summer of 1915, the company received an Experimental license for station 2XG, located at its Highbridge laboratory. In late 1916, de Forest renewed the entertainment broadcasts he had suspended in 1910, now using the superior capabilities of vacuum-tube equipment. 2XG's debut program aired on October 26, 1916, as part of an arrangement with the

In 1921, de Forest ended most of his radio research in order to concentrate on developing an optical sound-on-film process called Phonofilm. In 1919 he filed the first patent for the new system, which improved upon earlier work by Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership

In 1921, de Forest ended most of his radio research in order to concentrate on developing an optical sound-on-film process called Phonofilm. In 1919 he filed the first patent for the new system, which improved upon earlier work by Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership

The grid Audion, which de Forest called "my greatest invention", and the vacuum tubes developed from it, dominated the field of

The grid Audion, which de Forest called "my greatest invention", and the vacuum tubes developed from it, dominated the field of

De Forest was married four times, with the first three marriages ending in divorce:

* Lucille Sheardown in February 1906. Divorced before the end of the year.

* Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (1883–1971) on February 14, 1908. They had a daughter, Harriet, but were separated by 1909 and divorced in 1912.

* Mary Mayo (1892–1957) in December 1912. According to census records, in 1920 they were living with their infant daughter, Deena (born ca. 1919); divorced October 5, 1930 (per ''Los Angeles Times''). Mayo died December 30, 1957 in a fire in Los Angeles.

*

De Forest was married four times, with the first three marriages ending in divorce:

* Lucille Sheardown in February 1906. Divorced before the end of the year.

* Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (1883–1971) on February 14, 1908. They had a daughter, Harriet, but were separated by 1909 and divorced in 1912.

* Mary Mayo (1892–1957) in December 1912. According to census records, in 1920 they were living with their infant daughter, Deena (born ca. 1919); divorced October 5, 1930 (per ''Los Angeles Times''). Mayo died December 30, 1957 in a fire in Los Angeles.

*

by Lee de Forest, ''Popular Mechanics'', December 1940, pp. 154–159, 358, 360, 362, 364. * "So I repeat that while theoretically and technically television may be feasible, yet commercially and financially, I consider it an impossibility; a development of which we need not waste little time in dreaming." – 1926 * "To place a man in a multi-stage rocket and project him into the controlling gravitational field of the moon where the passengers can make scientific observations, perhaps land alive, and then return to earth—all that constitutes a wild dream worthy of"De Forest Says Space Travel Is Impossible"

(AP), ''Lewiston (Idaho) Morning Tribune'', February 25, 1957. * "I do not foresee 'spaceships' to the moon or Mars. Mortals must live and die on Earth or within its atmosphere!" – 1952 * "As a growing competitor to the tube amplifier comes now the Bell Laboratories’ transistor, a three-electrode germanium crystal of amazing amplification power, of wheat-grain size and low cost. Yet its frequency limitations, a few hundred kilocycles, and its strict power limitations will never permit its general replacement of the Audion amplifier." – 1952 * "I came, I saw, I invented—it's that simple—no need to sit and think—it's all in your imagination."

''Saga of the Vacuum Tube''

(Howard W. Sams and Company, 1977). Tyne was a research associate with the

LINK

Lee de Forest, American Inventor

(leedeforest.com) *

Lee de Forest biography

(ethw.org)

Lee de Forest biography

at

"Who said Lee de Forest was the 'Father of Radio'?"

by Stephen Greene, ''Mass Comm Review'', February 1991.

"Practical Pointers on the Audion"

by A. B. Cole, Sales Manager – De Forest Radio Tel. & Tel. Co., ''QST'', March 1916, pp. 41–44. (wikisource.org)

"A History of the Regeneration Circuit: From Invention to Patent Litigation

by Sungook Hong, Seoul National University (PDF)

"De Forest Phonofilm Co. Inc. on White House grounds"

(1924) (shorpy.com)

Guide to the Lee De Forest Papers 1902–1953

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:De Forest, Lee 1873 births 1961 deaths 20th-century American inventors Academy Honorary Award recipients American agnostics American anti-fascists American electrical engineers Burials at San Fernando Mission Cemetery California Republicans History of radio Illinois Institute of Technology faculty IEEE Edison Medal recipients IEEE Medal of Honor recipients Naval Consulting Board Northfield Mount Hermon School alumni People from Council Bluffs, Iowa Radio pioneers Yale School of Engineering & Applied Science alumni

inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

and a fundamentally important early pioneer in electronics

The field of electronics is a branch of physics and electrical engineering that deals with the emission, behaviour and effects of electrons using electronic devices. Electronics uses active devices to control electron flow by amplification ...

. He invented the first electronic device for controlling current flow; the three-element " Audion" triode

A triode is an electronic amplifying vacuum tube (or ''valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated filament or cathode, a grid, and a plate (anode). Developed from Lee De Forest's ...

vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

in 1906. This started the Electronic Age, and enabled the development of the electronic amplifier

An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a signal (a time-varying voltage or current). It may increase the power significantly, or its main effect may be to boost t ...

and oscillator

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value (often a point of equilibrium) or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum ...

. These made radio broadcasting

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

and long distance telephone lines possible, and led to the development of talking motion picture

A sound film is a motion picture with synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, but decades passed before ...

s, among countless other applications.

He had over 300 patents worldwide, but also a tumultuous career— he boasted that he made, then lost, four fortunes. He was also involved in several major patent lawsuits, spent a substantial part of his income on legal bills, and was even tried (and acquitted) for mail fraud.

Despite this, he was recognised for his pioneering work with the 1922 IEEE Medal of Honor

The IEEE Medal of Honor is the highest recognition of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It has been awarded since 1917, when its first recipient was Major Edwin H. Armstrong. It is given for an exceptional contributi ...

, the 1923 Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

Elliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848. The ...

and the 1946 American Institute of Electrical Engineers Edison Medal.

Early life

Lee de Forest was born in 1873 inCouncil Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Metropolitan Area. It is loc ...

, the son of Anna Margaret ( Robbins) and Henry Swift DeForest. He was a direct descendant of Jessé de Forest, the leader of a group of Walloon Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster B ...

who fled Europe in the 17th century due to religious persecution.

De Forest's father was a Congregational Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

minister who hoped his son would also become a pastor. In 1879 the elder de Forest became president of the American Missionary Association's Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama

Talladega (, also ) is the county seat of Talladega County, Alabama, United States. It was incorporated in 1835. At the 2020 census, the population was 15,861. Talladega is approximately east of one of the state’s biggest cities, Birmingham.

...

, a school "open to all of either sex, without regard to sect, race, or color", and which educated primarily African-Americans. Many of the local white citizens resented the school and its mission, and Lee spent most of his youth in Talladega isolated from the white community, with several close friends among the black children of the town.

De Forest prepared for college by attending Mount Hermon Boys' School in Mount Hermon, Massachusetts for two years, beginning in 1891. In 1893, he enrolled in a three-year course of studies at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the w ...

's Sheffield Scientific School

Sheffield Scientific School was founded in 1847 as a school of Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, for instruction in science and engineering. Originally named the Yale Scientific School, it was renamed in 1861 in honor of Joseph E. Sheffiel ...

in New Haven, Connecticut, on a $300 per year scholarship that had been established for relatives of David de Forest. Convinced that he was destined to become a famous—and rich—inventor, and perpetually short of funds, he sought to interest companies with a series of devices and puzzles he created, and expectantly submitted essays in prize competitions, all with little success.

After completing his undergraduate studies, in September 1896 de Forest began three years of postgraduate work. However, his electrical experiments had a tendency to blow fuses, causing building-wide blackouts. Even after being warned to be more careful, he managed to douse the lights during an important lecture by Professor Charles S. Hastings, who responded by having de Forest expelled from Sheffield.

With the outbreak of the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

in 1898, de Forest enrolled in the Connecticut Volunteer Militia Battery as a bugler, but the war ended and he was mustered out without ever leaving the state. He then completed his studies at Yale's Sloane Physics Laboratory, earning a Doctorate in 1899 with a dissertation on the "Reflection of Hertzian Waves from the Ends of Parallel Wires", supervised by theoretical physicist Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs (; February 11, 1839 – April 28, 1903) was an American scientist who made significant theoretical contributions to physics, chemistry, and mathematics. His work on the applications of thermodynamics was instrumental in ...

.

Early radio work

Reflecting his pioneering work, de Forest has sometimes been credited as the "Father of Radio", an honorific which he adopted as the title of his 1950 autobiography. In the late 1800s he became convinced there was a great future in radiotelegraphic communication (then known as " wireless telegraphy"), but Italian

Reflecting his pioneering work, de Forest has sometimes been credited as the "Father of Radio", an honorific which he adopted as the title of his 1950 autobiography. In the late 1800s he became convinced there was a great future in radiotelegraphic communication (then known as " wireless telegraphy"), but Italian Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italian inventor and electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based wireless telegraph system. This led to Marconi ...

, who received his first patent in 1896, was already making impressive progress in both Europe and the United States. One drawback of Marconi's approach was his use of a coherer

The coherer was a primitive form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers during the wireless telegraphy era at the beginning of the 20th century. Its use in radio was based on the 1890 findings of French physicist Édouard Bran ...

as a receiver, which, while providing for permanent records, was also slow (after each received Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

dot or dash, it had to be tapped to restore operation), insensitive, and not very reliable. De Forest was determined to devise a better system, including a self-restoring detector that could receive transmissions by ear, thus making it capable of receiving weaker signals and also allowing faster Morse code sending speeds.

After making unsuccessful inquiries about employment with Nikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla ( ; ,"Tesla"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 1856 – 7 January 1943 ...

and Marconi, de Forest struck out on his own. His first job after leaving Yale was with the ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; 1856 – 7 January 1943 ...

Western Electric Company

The Western Electric Company was an American electrical engineering and manufacturing company officially founded in 1869. A wholly owned subsidiary of American Telephone & Telegraph for most of its lifespan, it served as the primary equipment ...

's telephone lab in Chicago, Illinois. While there he developed his first receiver, which was based on findings by two German scientists, Drs. A. Neugschwender and Emil Aschkinass. Their original design consisted of a mirror in which a narrow, moistened slit had been cut through the silvered back. Attaching a battery and telephone receiver, they could hear sound changes in response to radio signal impulses. De Forest, along with Ed Smythe, a co-worker who provided financial and technical help, developed variations they called "responders".

A series of short-term positions followed, including three unproductive months with Professor Warren S. Johnson

Warren Seymour Johnson (November 6, 1847 – December 5, 1911) was an American college professor who was frustrated by his inability to regulate individual classroom temperatures. His multi-zone pneumatic control system solved the problem. Johnson ...

's American Wireless Telegraph Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and work as an assistant editor of the '' Western Electrician'' in Chicago. With radio research his main priority, de Forest next took a night teaching position at the Lewis Institute

Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Tracing its history to 1890, the present name was adopted upon the merger of the Armour Institute and Lewis Institute in 1940. The ...

, which freed him to conduct experiments at the Armour Institute. By 1900, using a spark-coil transmitter and his responder receiver, de Forest expanded his transmitting range to about seven kilometers (four miles). Professor Clarence Freeman of the Armour Institute became interested in de Forest's work and developed a new type of spark transmitter.

De Forest soon felt that Smythe and Freeman were holding him back, so in the fall of 1901 he made the bold decision to go to New York to compete directly with Marconi in transmitting race results for the International Yacht races. Marconi had already made arrangements to provide reports for the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. new ...

, which he had successfully done for the 1899 contest. De Forest contracted to do the same for the smaller Publishers' Press Association.

The race effort turned out to be an almost total failure. The Freeman transmitter broke down—in a fit of rage, de Forest threw it overboard—and had to be replaced by an ordinary spark coil. Even worse, the American Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Company, which claimed its ownership of Amos Dolbear

Amos Emerson Dolbear (November 10, 1837 – February 23, 1910) was an American physicist and inventor. Dolbear researched electrical spark conversion into sound waves and electrical impulses. He was a professor at University of Kentucky in Lex ...

's 1886 patent for wireless communication meant it held a monopoly for all wireless communication in the United States, had also set up a powerful transmitter. None of these companies had effective tuning for their transmitters, so only one could transmit at a time without causing mutual interference. Although an attempt was made to have the three systems avoid conflicts by rotating operations over five-minute intervals, the agreement broke down, resulting in chaos as the simultaneous transmissions clashed with each other. De Forest ruefully noted that under these conditions the only successful "wireless" communication was done by visual semaphore "wig-wag" flags. (The 1903 International Yacht races would be a repeat of 1901—Marconi worked for the Associated Press, de Forest for the Publishers' Press Association, and the unaffiliated International Wireless Company (successor to 1901's American Wireless Telephone and Telegraph) operated a high-powered transmitter that was used primarily to drown out the other two.)

American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company

Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-born inventor, who did a majority of his work in the United States and also claimed U.S. citizenship through his American-born father. During his life he received hundre ...

demonstrated an electrolytic detector, and de Forest developed a variation, which he called the "spade detector", claiming it did not infringe on Fessenden's patents. Fessenden, and the U.S. courts, did not agree, and court injunctions enjoined American De Forest from using the device.

Meanwhile, White set in motion a series of highly visible promotions for American DeForest: "Wireless Auto No.1" was positioned on Wall Street to "send stock quotes" using an unmuffled spark transmitter to loudly draw the attention of potential investors, in early 1904 two stations were established at Wei-hai-Wei on the Chinese mainland and aboard the Chinese steamer '' SS Haimun'', which allowed war correspondent Captain Lionel James of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' of London to report on the brewing Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, and later that year a tower, with "DEFOREST" arrayed in lights, was erected on the grounds of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World's Fair, was an World's fair, international exposition held in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, from April 30 to December 1, 1904. Local, state, and federal funds tota ...

in Saint Louis, Missouri, where the company won a gold medal for its radiotelegraph demonstrations. (Marconi withdrew from the Exposition when he learned de Forest would be there).

The company's most important early contract was the construction, in 1905–1906, of five high-powered radiotelegraph stations for the U.S. Navy, located in Panama, Pensacola and Key West, Florida, Guantanamo, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. It also installed shore stations along the Atlantic Coast and Great Lakes, and equipped shipboard stations. But the main focus was selling stock at ever more inflated prices, spurred by the construction of promotional inland stations. Most of these inland stations had no practical use and were abandoned once the local stock sales slowed.

De Forest eventually came into conflict with his company's management. His main complaint was the limited support he got for conducting research, while company officials were upset with de Forest's inability to develop a practical receiver free of patent infringement. (This problem was finally resolved with the invention of the carborundum

Silicon carbide (SiC), also known as carborundum (), is a hard chemical compound containing silicon and carbon. A semiconductor, it occurs in nature as the extremely rare mineral moissanite, but has been mass-produced as a powder and crystal si ...

crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macro ...

detector by another company employee, General Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody (October 23, 1842 – January 1, 1933) was an American army officer, businessman, and inventor. Known in his own time for his work with the Army's Weather Bureau, he invented the carborundum radio detector in 1906. I ...

). On November 28, 1906, in exchange for $1000 (half of which was claimed by an attorney) and the rights to some early Audion detector patents, de Forest turned in his stock and resigned from the company that bore his name. American DeForest was then reorganized as the United Wireless Telegraph Company

The United Wireless Telegraph Company was the largest radio communications firm in the United States, from its late-1906 formation until its bankruptcy and takeover by Marconi interests in mid-1912. At the time of its demise, the company was opera ...

, and would be the dominant U.S. radio communications firm, albeit propped up by massive stock fraud, until its bankruptcy in 1912.

Radio Telephone Company

De Forest moved quickly to re-establish himself as an independent inventor, working in his own laboratory in the Parker Building in New York City. The Radio Telephone Company was incorporated in order to promote his inventions, with James Dunlop Smith, a former American DeForest salesman, as president, and de Forest the vice president (De Forest preferred the termradio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a tr ...

, which up to now had been primarily used in Europe, over wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

).

Arc radiotelephone development

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition,

At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, Valdemar Poulsen

Valdemar Poulsen (23 November 1869 – 23 July 1942) was a Danish engineer who made significant contributions to early radio technology. He developed a magnetic wire recorder called the telegraphone in 1898 and the first continuous wave rad ...

had presented a paper on an arc transmitter

The arc converter, sometimes called the arc transmitter, or Poulsen arc after Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen who invented it in 1903, was a variety of spark transmitter used in early wireless telegraphy. The arc converter used an electric arc t ...

, which unlike the discontinuous pulses produced by spark transmitters, created steady "continuous wave" signals that could be used for amplitude modulated

Amplitude modulation (AM) is a modulation technique used in electronic communication, most commonly for transmitting messages with a radio wave. In amplitude modulation, the amplitude (signal strength) of the wave is varied in proportion to t ...

(AM) audio transmissions. Although Poulsen had patented his invention, de Forest claimed to have come up with a variation that allowed him to avoid infringing on Poulsen's work. Using his "sparkless" arc transmitter, de Forest first transmitted audio across a lab room on December 31, 1906, and by February was making experimental transmissions, including music produced by Thaddeus Cahill's telharmonium

The Telharmonium (also known as the Dynamophone) was an early electrical organ, developed by Thaddeus Cahill c. 1896 and patented in 1897.

, filed 1896-02-04.

The electrical signal from the Telharmonium was transmitted over wires; it was hear ...

, that were heard throughout the city.

On July 18, 1907, de Forest made the first ship-to-shore transmissions by radiotelephone—race reports for the Annual Inter-Lakes Yachting Association (I-LYA) Regatta held on Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also ha ...

—which were sent from the steam yacht ''Thelma'' to his assistant, Frank E. Butler, located in the Fox's Dock Pavilion on South Bass Island. De Forest also interested the U.S. Navy in his radiotelephone, which placed a rush order to have 26 arc sets installed for its Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the group of United States Navy battleships which completed a journey around the globe from December 16, 1907 to February 22, 1909 by order of President Theodore Roosevelt. Its mission was ...

around-the-world voyage that began in late 1907. However, at the conclusion of the circumnavigation the sets were declared to be too unreliable to meet the Navy's needs and removed.

The company set up a network of radiotelephone stations along the Atlantic coast and the Great Lakes, for coastal ship navigation. However, the installations proved unprofitable, and by 1911 the parent company and its subsidiaries were on the brink of bankruptcy.

Initial broadcasting experiments

De Forest also used the arc-transmitter to conduct some of the earliest experimental entertainment radio broadcasts.

De Forest also used the arc-transmitter to conduct some of the earliest experimental entertainment radio broadcasts. Eugenia Farrar

Eugenia Farrar (1875—1966), whose full name was Ada Eugenia Hildegard von Boos Farrar, was a mezzo-soprano singer and philanthropist. She was born in Sweden and lived most of her life in New York City. In the fall of 1907 she gave what is comm ...

sang "I Love You Truly" in an unpublicized test from his laboratory in 1907, and in 1908, on de Forest's Paris honeymoon, musical selections were broadcast from the Eiffel Tower as a part of demonstrations of the arc-transmitter. In early 1909, in what may have been the first public speech by radio, de Forest's mother-in-law, Harriot Stanton Blatch

Harriot Eaton Blatch ( Stanton; January 20, 1856–November 20, 1940) was an American writer and suffragist. She was the daughter of pioneering women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Biography

Harriot Eaton Stanton was born, the six ...

, made a broadcast supporting women's suffrage.

More ambitious demonstrations followed. A series of tests in conjunction with the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is opera ...

House in New York City were conducted to determine whether it was practical to broadcast opera performances live from the stage. ''Tosca

''Tosca'' is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It premiered at the Teatro Costanzi in Rome on 14 January 1900. The work, based on Victorien Sardou's 1887 French-language dramati ...

'' was performed on January 12, 1910, and the next day's test included Italian tenor Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

. On February 24, the Manhattan Opera Company's Mme. Mariette Mazarin sang "La Habanera" from ''Carmen'' and selections from the controversial "Elektra" over a transmitter located in de Forest's lab. But these tests showed that the idea was not yet technically feasible, and de Forest would not make any additional entertainment broadcasts until late 1916, when more capable vacuum-tube equipment became available.

"Grid" Audion detector

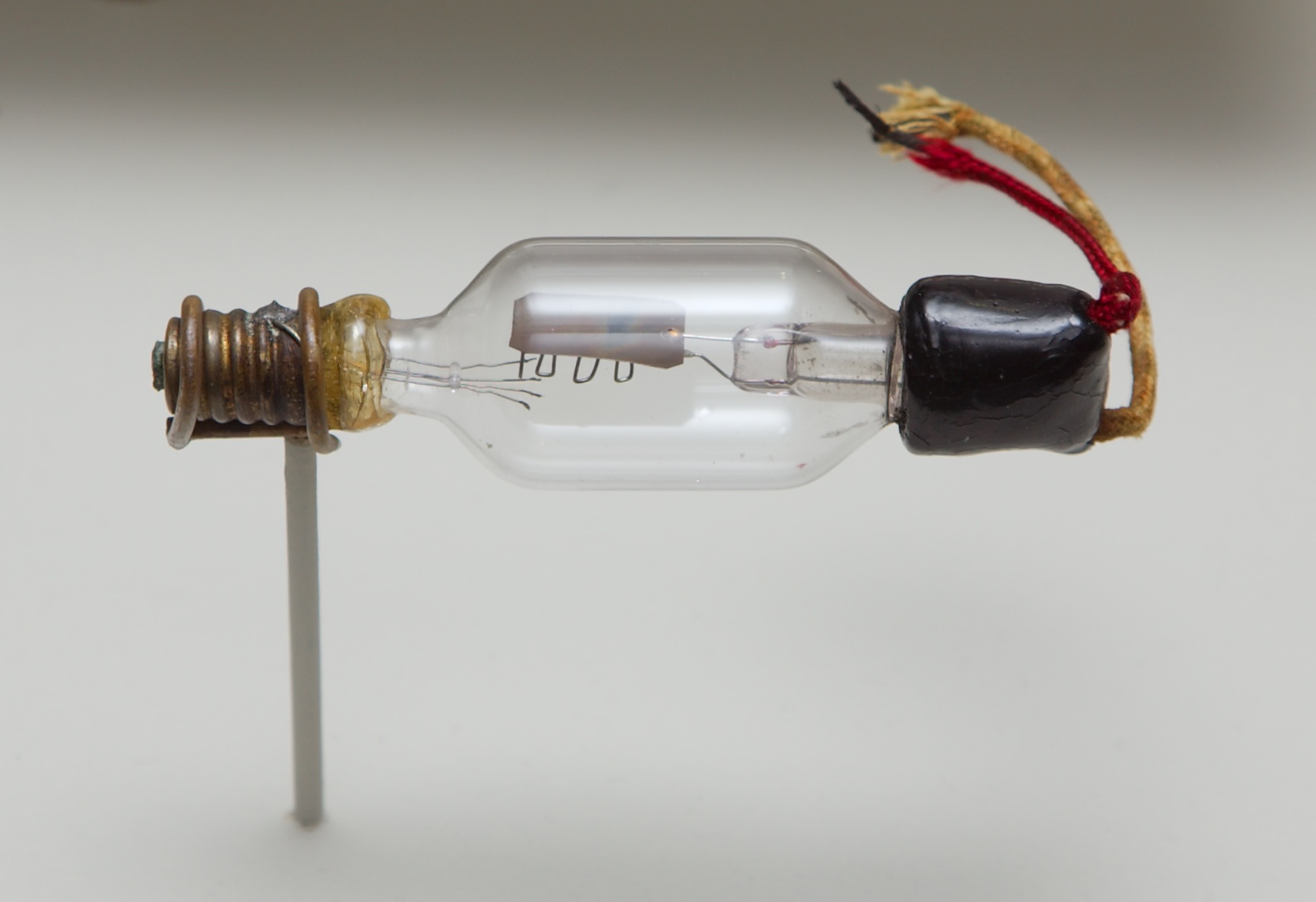

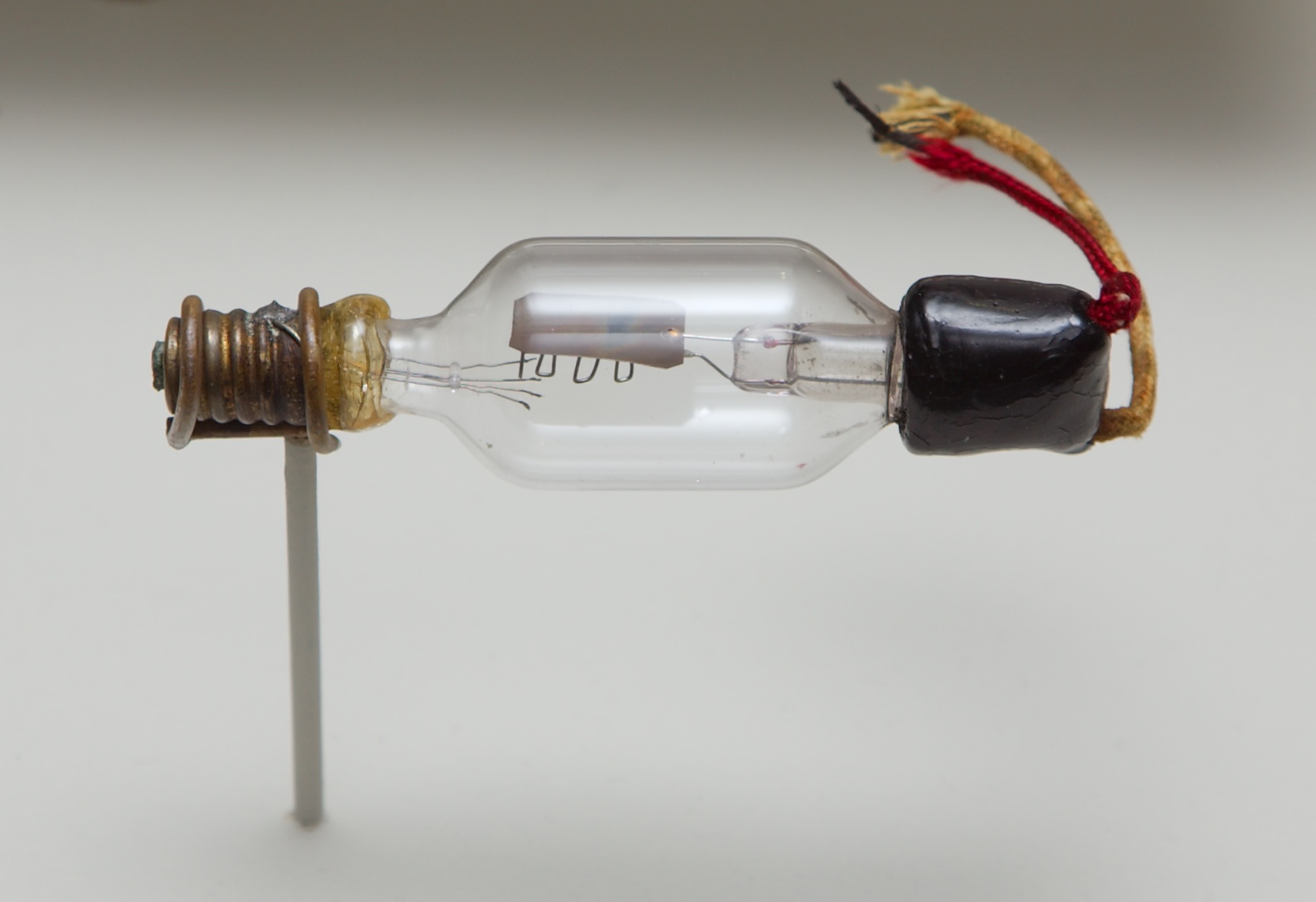

De Forest's most famous invention was the "grid Audion", which was the first successful three-element (triode

A triode is an electronic amplifying vacuum tube (or ''valve'' in British English) consisting of three electrodes inside an evacuated glass envelope: a heated filament or cathode, a grid, and a plate (anode). Developed from Lee De Forest's ...

) vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

, and the first device which could amplify electrical signals. He traced its inspiration to 1900, when, experimenting with a spark-gap transmitter, he briefly thought that the flickering of a nearby gas flame might be in response to electromagnetic pulses. With further tests he soon determined that the cause of the flame fluctuations was due to air pressure changes produced by the loud sound of the spark. Still, he was intrigued by the idea that, properly configured, it might be possible to use a flame or something similar to detect radio signals.

After determining that an open flame was too susceptible to ambient air currents, de Forest investigated whether ionized gases, heated and enclosed in a partially evacuated glass tube, could be used instead. In 1905 to 1906 he developed various configurations of glass-tube devices, which he gave the general name of "Audions". The first Audions had only two electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials ...

s, and on October 25, 1906, de Forest filed a patent for diode

A diode is a two-terminal electronic component that conducts current primarily in one direction (asymmetric conductance); it has low (ideally zero) resistance in one direction, and high (ideally infinite) resistance in the other.

A diod ...

vacuum tube detector, that was granted U.S. patent number 841387 on January 15, 1907. Subsequently, a third "control" electrode was added, originally as a surrounding metal cylinder or a wire coiled around the outside of the glass tube. None of these initial designs worked particularly well. De Forest gave a presentation of his work to date to the October 26, 1906 New York meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, which was reprinted in two parts in late 1907 in the ''Scientific American Supplement''. He was insistent that a small amount of residual gas was necessary for the tubes to operate properly. However, he also admitted that "I have arrived as yet at no completely satisfactory theory as to the exact means by which the high-frequency oscillations affect so markedly the behavior of an ionized gas."

In late 1906, de Forest made a breakthrough when he reconfigured the control electrode, moving it from outside the tube envelope to a position inside the tube between the

In late 1906, de Forest made a breakthrough when he reconfigured the control electrode, moving it from outside the tube envelope to a position inside the tube between the filament

The word filament, which is descended from Latin ''filum'' meaning " thread", is used in English for a variety of thread-like structures, including:

Astronomy

* Galaxy filament, the largest known cosmic structures in the universe

* Solar filament ...

and the plate. He called the intermediate electrode a ''grid'', reportedly due to its similarity to the "gridiron" lines on American football playing fields. Experiments conducted with his assistant, John V. L. Hogan, convinced him that he had discovered an important new radio detector. He quickly prepared a patent application which was filed on January 29, 1907, and received on February 18, 1908. Because the grid-control Audion was the only configuration to become commercially valuable, the earlier versions were forgotten, and the term ''Audion'' later became synonymous with just the grid type. It later also became known as the triode.

The grid Audion was the first device to amplify, albeit only slightly, the strength of received radio signals. However, to many observers it appeared that de Forest had done nothing more than add the grid electrode to an existing detector configuration, the Fleming valve, which also consisted of a filament and plate enclosed in an evacuated glass tube. De Forest passionately denied the similarly of the two devices, claiming his invention was a relay that amplified currents, while the Fleming valve was merely a rectifier that converted alternating current to direct current. (For this reason, de Forest objected to his Audion being referred to as "a valve".) The U.S. courts were not convinced, and ruled that the grid Audion did in fact infringe on the Fleming valve patent, now held by Marconi. In contrast, Marconi admitted that the addition of the third electrode was a patentable improvement, and the two sides agreed to license each other so that both could manufacture three-electrode tubes in the United States. (De Forest's European patents had lapsed because he did not have the funds needed to renew them).

Because of its limited uses and the great variability in the quality of individual units, the grid Audion would be rarely used during the first half-decade after its invention. In 1908, John V. L. Hogan reported that "The Audion is capable of being developed into a really efficient detector, but in its present forms is quite unreliable and entirely too complex to be properly handled by the usual wireless operator."

Employment at Federal Telegraph

In May 1910, the Radio Telephone Company and its subsidiaries were reorganized as the North American Wireless Corporation, but financial difficulties meant that the company's activities had nearly come to a halt. De Forest moved to San Francisco, California, and in early 1911 took a research job at the Federal Telegraph Company, which produced long-range radiotelegraph systems using high-powered

In May 1910, the Radio Telephone Company and its subsidiaries were reorganized as the North American Wireless Corporation, but financial difficulties meant that the company's activities had nearly come to a halt. De Forest moved to San Francisco, California, and in early 1911 took a research job at the Federal Telegraph Company, which produced long-range radiotelegraph systems using high-powered Poulsen arc

The arc converter, sometimes called the arc transmitter, or Poulsen arc after Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen who invented it in 1903, was a variety of spark transmitter used in early wireless telegraphy. The arc converter used an electric arc t ...

s.

Audio frequency amplification

One of de Forest's areas of research at Federal Telegraph was improving the reception of signals, and he came up with the idea of strengthening the audio frequency output from a grid Audion by feeding it into a second tube for additional amplification. He called this a "cascade amplifier", which eventually consisted of chaining together up to three Audions. At this time the American Telephone and Telegraph Company was researching ways to amplify telephone signals to provide better long-distance service, and it was recognized that de Forest's device had potential as a telephone line repeater. In mid-1912 an associate, John Stone Stone, contacted AT&T to arrange for de Forest to demonstrate his invention. It was found that de Forest's "gassy" version of the Audion could not handle even the relatively low voltages used by telephone lines. (Owing to the way he constructed the tubes, de Forest's Audions would cease to operate with too high a vacuum.) However, careful research by Dr. Harold D. Arnold and his team at AT&T's Western Electric subsidiary determined that improving the tube's design would allow it to be more fully evacuated, and the high vacuum allowed it to operate at telephone-line voltages. With these changes the Audion evolved into a modern electron-discharge vacuum tube, using electron flows rather than ions. (Dr.Irving Langmuir

Irving Langmuir (; January 31, 1881 – August 16, 1957) was an American chemist, physicist, and engineer. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932 for his work in surface chemistry.

Langmuir's most famous publication is the 1919 ar ...

at the General Electric Corporation made similar findings, and both he and Arnold attempted to patent the "high vacuum" construction, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1931 that this modification could not be patented).

After a delay of ten months, in July 1913 AT&T, through a third party who disguised his link to the telephone company, purchased the wire rights to seven Audion patents for $50,000. De Forest had hoped for a higher payment, but was again in bad financial shape and was unable to bargain for more. In 1915, AT&T used the innovation to conduct the first transcontinental telephone calls, in conjunction with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition at San Francisco.

Reorganized Radio Telephone Company

Radio Telephone Company officials had engaged in some of the same stock selling excesses that had taken place at American DeForest, and as part of the U.S. government's crackdown on stock fraud, in March 1912 de Forest, plus four other company officials, were arrested and charged with "use of the mails to defraud". Their trials took place in late 1913, and while three of the defendants were found guilty, de Forest was acquitted. With the legal problems behind him, de Forest reorganized his company as the DeForest Radio Telephone Company, and established a laboratory at 1391 Sedgewick Avenue in the Highbridge section of the Bronx in New York City. The company's limited finances were boosted by the sale, in October 1914, of the commercial Audion patent rights for radio signalling to AT&T for $90,000, with de Forest retaining the rights for sales for "amateur and experimental use". In October 1915 AT&T conducted test radio transmissions from the Navy's station in Arlington, Virginia that were heard as far away as Paris and Hawaii. The Radio Telephone Company began selling "Oscillion" power tubes to amateurs, suitable for radio transmissions. The company wanted to keep a tight hold on the tube business, and originally maintained a policy that retailers had to require their customers to return a worn-out tube before they could get a replacement. This style of business encouraged others to make and sell unlicensed vacuum tubes which did not impose a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded in 1915 by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco, whose Audio Tron tubes cost less but were of equal or higher quality. The de Forest company sued Audio Tron Sales, eventually settling out of court.

In April 1917, the company's remaining commercial radio patent rights were sold to AT&T's Western Electric subsidiary for $250,000. During World War I, the Radio Telephone Company prospered from sales of radio equipment to the military. However, it also became known for the poor quality of its vacuum tubes, especially compared to those produced by major industrial manufacturers such as General Electric and Western Electric.

The Radio Telephone Company began selling "Oscillion" power tubes to amateurs, suitable for radio transmissions. The company wanted to keep a tight hold on the tube business, and originally maintained a policy that retailers had to require their customers to return a worn-out tube before they could get a replacement. This style of business encouraged others to make and sell unlicensed vacuum tubes which did not impose a return policy. One of the boldest was Audio Tron Sales Company founded in 1915 by Elmer T. Cunningham of San Francisco, whose Audio Tron tubes cost less but were of equal or higher quality. The de Forest company sued Audio Tron Sales, eventually settling out of court.

In April 1917, the company's remaining commercial radio patent rights were sold to AT&T's Western Electric subsidiary for $250,000. During World War I, the Radio Telephone Company prospered from sales of radio equipment to the military. However, it also became known for the poor quality of its vacuum tubes, especially compared to those produced by major industrial manufacturers such as General Electric and Western Electric.

Regeneration controversy

Beginning in 1912, there was increased investigation of vacuum-tube capabilities, simultaneously by numerous inventors in multiple countries, who identified additional important uses for the device. These overlapping discoveries led to complicated legal disputes over priority, perhaps the most bitter being one in the United States between de Forest andEdwin Howard Armstrong

Edwin Howard Armstrong (December 18, 1890 – February 1, 1954) was an American electrical engineer and inventor, who developed FM (frequency modulation) radio and the superheterodyne receiver system. He held 42 patents and received numerous awa ...

over the discovery of regeneration (also known as the "feedback circuit" and, by de Forest, as the "ultra-audion").

Beginning in 1913 Armstrong prepared papers and gave demonstrations that comprehensively documented how to employ three-element vacuum tubes in circuits that amplified signals to stronger levels than previously thought possible, and that could also generate high-power oscillations usable for radio transmission. In late 1913 Armstrong applied for patents covering the regenerative circuit

A regenerative circuit is an amplifier circuit that employs positive feedback (also known as regeneration or reaction). Some of the output of the amplifying device is applied back to its input so as to add to the input signal, increasing the a ...

, and on October 6, 1914 was issued for his discovery.

U.S. patent law included a provision for challenging grants if another inventor could prove prior discovery. With an eye to increasing the value of the patent portfolio that would be sold to Western Electric in 1917, beginning in 1915 de Forest filed a series of patent applications that largely copied Armstrong's claims, in the hopes of having the priority of the competing applications upheld by an interference hearing at the patent office. Based on a notebook entry recorded at the time, de Forest asserted that, while working on the cascade amplifier, he had stumbled on August 6, 1912 across the feedback principle, which was then used in the spring of 1913 to operate a low-powered transmitter for heterodyne reception of Federal Telegraph arc transmissions. However, there was also strong evidence that de Forest was unaware of the full significance of this discovery, as shown by his lack of follow-up and continuing misunderstanding of the physics involved. In particular, it appeared that he was unaware of the potential for further development until he became familiar with Armstrong's research. De Forest was not alone in the interference determination—the patent office identified four competing claimants for its hearings, consisting of Armstrong, de Forest, General Electric's Langmuir, and a German, Alexander Meissner, whose application would be seized by the Office of Alien Property Custodian during World War I.

The subsequent legal proceedings become divided between two groups of court cases. The first court action began in January 1920 when Armstrong, with Westinghouse, which purchased his patent, sued the De Forest Company in district court for infringement of patent 1,113,149. On May 17, 1921 the court ruled that the lack of awareness and understanding on de Forest's part, in addition to the fact that he had made no immediate advances beyond his initial observation, made implausible his attempt to prevail as inventor.

However, a second series of court cases, which were the result of the patent office interference proceeding, had a different outcome. The interference board had also sided with Armstrong, and de Forest appealed its decision to the District of Columbia district court. On May 8, 1924, that court concluded that the evidence, beginning with the 1912 notebook entry, was sufficient to establish de Forest's priority. Now on the defensive, Armstrong's side tried to overturn the decision, but these efforts, which twice went before the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1928 and 1934, were unsuccessful.

This judicial ruling meant that Lee de Forest was now legally recognized in the United States as the inventor of regeneration. However, much of the engineering community continued to consider Armstrong to be the actual developer, with de Forest viewed as someone who skillfully used the patent system to get credit for an invention to which he had barely contributed. Following the 1934 Supreme Court decision, Armstrong attempted to return his Institute of Radio Engineers (present-day Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) is a 501(c)(3) professional association for electronic engineering and electrical engineering (and associated disciplines) with its corporate office in New York City and its operation ...

) Medal of Honor, which had been awarded to him in 1917 "in recognition of his work and publications dealing with the action of the oscillating and non-oscillating audion", but the organization's board refused to let him, stating that it "strongly affirms the original award". The practical effect of de Forest's victory was that his company was free to sell products that used regeneration, for during the controversy, which became more a personal feud than a business dispute, Armstrong tried to block the company from even being licensed to sell equipment under his patent.

De Forest regularly responded to articles which he thought exaggerated Armstrong's contributions with animosity that continued even after Armstrong's 1954 suicide. Following the publication of Carl Dreher's "E. H. Armstrong, the Hero as Inventor" in the August 1956 Harper's magazine, de Forest wrote the author, describing Armstrong as "exceedingly arrogant, brow beating, even brutal...", and defending the Supreme Court decision in his favor.

Renewed broadcasting activities

Columbia Graphophone Company

Columbia Graphophone Co. Ltd. was one of the earliest gramophone companies in the United Kingdom.

Founded in 1917 as an offshoot of the American Columbia Phonograph Company, it became an independent British-owned company in 1922 in a managemen ...

to promote its recordings, which included "announcing the title and 'Columbia Gramophone 'sic''Company' with each playing". Beginning November 1, the "Highbridge Station" offered a nightly schedule featuring the Columbia recordings.

These broadcasts were also used to advertise "the products of the DeForest Radio Co., mostly the radio parts, with all the zeal of our catalogue and price list", until comments by Western Electric engineers caused de Forest enough embarrassment to make him decide to eliminate the direct advertising. The station also made the first audio broadcast of election reports—in earlier elections, stations that broadcast results had used Morse code—providing news of the November 1916 Wilson-Hughes presidential election. The ''New York American

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' installed a private wire and bulletins were sent out every hour. About 2,000 listeners heard ''The Star-Spangled Banner'' and other anthems, songs, and hymns.

With the entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, all civilian radio stations were ordered to shut down, so 2XG was silenced for the duration of the war. The ban on civilian stations was lifted on October 1, 1919, and 2XG soon renewed operation, with the Brunswick-Balke-Collender company now supplying the phonograph records. In early 1920, de Forest moved the station's transmitter from the Bronx to Manhattan, but did not have permission to do so, so district Radio Inspector Arthur Batcheller ordered the station off the air. De Forest's response was to return to San Francisco in March, taking 2XG's transmitter with him. A new station, 6XC, was established as "The California Theater station", which de Forest later stated was the "first radio-telephone station devoted solely" to broadcasting to the public.

Later that year a de Forest associate, Clarence "C.S." Thompson, established Radio News & Music, Inc., in order to lease de Forest radio transmitters to newspapers interested in setting up their own broadcasting stations. In August 1920, The ''Detroit News'' began operation of "The Detroit News Radiophone", initially with the callsign 8MK, which later became broadcasting station WWJ.

Phonofilm sound-on-film process

In 1921, de Forest ended most of his radio research in order to concentrate on developing an optical sound-on-film process called Phonofilm. In 1919 he filed the first patent for the new system, which improved upon earlier work by Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership

In 1921, de Forest ended most of his radio research in order to concentrate on developing an optical sound-on-film process called Phonofilm. In 1919 he filed the first patent for the new system, which improved upon earlier work by Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt and the German partnership Tri-Ergon

The Tri-Ergon sound-on-film system was developed from around 1919 by three German inventors, Josef Engl (1893–1942), Joseph Massolle (1889–1957), and Hans Vogt (1890–1979).

The system used a photoelectric recording method and a non-standa ...

. Phonofilm recorded the electrical waveforms produced by a microphone photographically onto film, using parallel lines of variable shades of gray, an approach known as "variable density", in contrast to "variable area" systems used by processes such as RCA Photophone. When the movie film was projected, the recorded information was converted back into sound, in synchronization with the picture.

From October 1921 to September 1922, de Forest lived in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

, Germany, meeting the Tri-Ergon developers (German inventors Josef Engl Josef may refer to

*Josef (given name)

*Josef (surname)

* ''Josef'' (film), a 2011 Croatian war film

*Musik Josef

Musik Josef is a Japanese manufacturer of musical instruments. It was founded by Yukio Nakamura, and is the only company in Japan spe ...

(1893–1942), Hans Vogt (1890–1979), and Joseph Massolle (1889–1957)) and investigating other European sound film systems. In April 1922 he announced that he would soon have a workable sound-on-film system. On March 12, 1923 he demonstrated Phonofilm to the press; this was followed on April 12, 1923 by a private demonstration to electrical engineers at the Engineering Society Building's Auditorium at 33 West 39th Street in New York City.

In November 1922, de Forest established the De Forest Phonofilm Company, located at 314 East 48th Street in New York City. But none of the Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

movie studios expressed interest in his invention, and because at this time these studios controlled all the major theater chains, this meant de Forest was limited to showing his experimental films in independent theaters (The Phonofilm Company would file for bankruptcy in September 1926.).

After recording stage performances (such as in vaudeville), speeches, and musical acts, on April 15, 1923 de Forest premiered 18 Phonofilm short films at the independent Rivoli Theater in New York City. Starting in May 1924, Max and Dave Fleischer used the Phonofilm process for their Song Car-Tune series of cartoons—featuring the " Follow the Bouncing Ball" gimmick. However, de Forest's choice of primarily filming short vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

acts, instead of full-length features, limited the appeal of Phonofilm to Hollywood studios.

De Forest also worked with Freeman Harrison Owens

Freeman Harrison Owens (July 20, 1890 – December 9, 1979) was an early American filmmaker and aerial photographer.

Biography

was born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the only child of Charles H. Owens and Christabel Harrison. He attended Pine Blu ...

and Theodore Case, using their work to perfect the Phonofilm system. However, de Forest had a falling out with both men. Due to de Forest's continuing misuse of Theodore Case's inventions and failure to publicly acknowledge Case's contributions, the Case Research Laboratory proceeded to build its own camera. That camera was used by Case and his colleague Earl Sponable to record Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a Republican lawyer from New England who climbed up the ladder of Ma ...

on August 11, 1924, which was one of the films shown by de Forest and claimed by him to be the product of his inventions.

Believing that de Forest was more concerned with his own fame and recognition than he was with actually creating a workable system of sound film, and because of his continuing attempts to downplay the contributions of the Case Research Laboratory in the creation of Phonofilm, Case severed his ties with de Forest in the fall of 1925. Case successfully negotiated an agreement to use his patents with studio head William Fox, owner of Fox Film Corporation, who marketed the innovation as Fox Movietone. Warner Brothers

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Warner Bros. or abbreviated as WB) is an American film and entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, California, and a subsidiary of Warner Bros. D ...

introduced a competing method for sound film, the Vitaphone

Vitaphone was a sound film system used for feature films and nearly 1,000 short subjects made by Warner Bros. and its sister studio First National from 1926 to 1931. Vitaphone was the last major analog sound-on-disc system and the only one ...

sound-on-disc process developed by Western Electric

The Western Electric Company was an American electrical engineering and manufacturing company officially founded in 1869. A wholly owned subsidiary of American Telephone & Telegraph for most of its lifespan, it served as the primary equipment ma ...

, with the August 6, 1926 release of the John Barrymore

John Barrymore (born John Sidney Blyth; February 14 or 15, 1882 – May 29, 1942) was an American actor on stage, screen and radio. A member of the Drew and Barrymore theatrical families, he initially tried to avoid the stage, and briefly att ...

film '' Don Juan''.

In 1927 and 1928, Hollywood expanded its use of sound-on-film systems, including Fox Movietone and RCA Photophone. Meanwhile, theater chain owner Isadore Schlesinger purchased the UK rights to Phonofilm and released short films of British music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Br ...

performers from September 1926 to May 1929. Almost 200 Phonofilm shorts were made, and many are preserved in the collections of the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

and the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

.

Later years and death

In April 1923, the De Forest Radio Telephone & Telegraph Company, which manufactured de Forest's Audions for commercial use, was sold to a group headed by Edward Jewett of Jewett-Paige Motors, which expanded the company's factory to cope with rising demand for radios. The sale also bought the services of de Forest, who was focusing his attention on newer innovations. De Forest's finances were badly hurt by the stock market crash of 1929, and research in mechanical television proved unprofitable. In 1934, he established a small shop to producediathermy

Diathermy is electrically induced heat or the use of high-frequency electromagnetic currents as a form of physical therapy and in surgical procedures. The earliest observations on the reactions of high-frequency electromagnetic currents upon the ...

machines, and, in a 1942 interview, still hoped "to make at least one more great invention".

De Forest was a vocal critic of many of the developments in the entertainment side of the radio industry. In 1940 he sent an open letter to the National Association of Broadcasters

The National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) is a trade association and lobby group representing the interests of commercial and non-commercial over-the-air radio and television broadcasters in the United States. The NAB represents more than ...

in which he demanded: "What have you done with my child, the radio broadcast? You have debased this child, dressed him in rags of ragtime, tatters of jive and boogie-woogie." That same year, de Forest and early TV engineer Ulises Armand Sanabria

Ulises Armand Sanabria (September 5, 1906 January 6, 1969) was born in southern Chicago of Puerto Rican and French-American parents. Sanabria is known for development of mechanical televisions and early terrestrial television broadcasts.

Care ...

presented the concept of a primitive unmanned combat air vehicle using a television camera

A professional video camera (often called a television camera even though its use has spread beyond television) is a high-end device for creating electronic moving images (as opposed to a movie camera, that earlier recorded the images on film). ...

and a jam-resistant radio control in a ''Popular Mechanics

''Popular Mechanics'' (sometimes PM or PopMech) is a magazine of popular science and technology, featuring automotive, home, outdoor, electronics, science, do-it-yourself, and technology topics. Military topics, aviation and transportation o ...

'' issue. In 1950 his autobiography, ''Father of Radio'', was published, although it sold poorly.

De Forest was the guest celebrity on the May 22, 1957, episode of the television show ''This Is Your Life This Is Your Life may refer to:

Television

* ''This Is Your Life'' (American franchise), an American radio and television documentary biography series hosted by Ralph Edwards

* ''This Is Your Life'' (Australian TV series), the Australian versio ...

'', where he was introduced as "the father of radio and the grandfather of television". He suffered a severe heart attack in 1958, after which he remained mostly bedridden. He died in Hollywood on June 30, 1961, aged 87, and was interred in San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Los Angeles, California. De Forest died relatively poor, with just $1,250 in his bank account.

Legacy

The grid Audion, which de Forest called "my greatest invention", and the vacuum tubes developed from it, dominated the field of

The grid Audion, which de Forest called "my greatest invention", and the vacuum tubes developed from it, dominated the field of electronics

The field of electronics is a branch of physics and electrical engineering that deals with the emission, behaviour and effects of electrons using electronic devices. Electronics uses active devices to control electron flow by amplification ...

for forty years, making possible long-distance telephone service, radio broadcasting

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

, television, and many other applications. It could also be used as an electronic switching element, and was later used in early digital electronics, including the first electronic computers, although the 1948 invention of the transistor

upright=1.4, gate (G), body (B), source (S) and drain (D) terminals. The gate is separated from the body by an insulating layer (pink).

A transistor is a semiconductor device used to Electronic amplifier, amplify or electronic switch, switch ...

would lead to microchips that eventually supplanted vacuum-tube technology. For this reason de Forest has been called one of the founders of the "electronic age".

According to Donald Beaver, his intense desire to overcome the deficiencies of his childhood account for his independence, self-reliance, and inventiveness. He displayed a strong desire to achieve, to conquer hardship, and to devote himself to a career of invention. "He possessed the qualities of the traditional tinkerer-inventor: visionary faith, self-confidence, perseverance, the capacity for sustained hard work."

De Forest's archives were donated by his widow to the Perham Electronic Foundation, which in 1973 opened the Foothills Electronics Museum at Foothill College

Foothill College is a public community college in Los Altos Hills, California. It is part of the Foothill–De Anza Community College District. It was founded on January 15, 1957, and offers 79 Associate degree programs, 1 Bachelor's degree ...

in Los Altos Hills, California. In 1991 the college closed the museum, breaking its contract. The foundation won a lawsuit and was awarded $775,000. The holdings were placed in storage for twelve years, before being acquired in 2003 by History San José and put on display as The Perham Collection of Early Electronics.

Awards and recognition

* Charter member, in 1912, of the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE). * Received the 1922 IREMedal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

, in "recognition for his invention of the three-electrode amplifier and his other contributions to radio".

* Awarded the 1923 Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memori ...

Elliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848. The ...

for "inventions embodied in the Audion".

* Received the 1946 American Institute of Electrical Engineers Edison Medal, "For the profound technical and social consequences of the grid-controlled vacuum tube which he had introduced".

* Honorary Academy Award

The Academy Honorary Award – instituted in 1950 for the 23rd Academy Awards (previously called the Special Award, which was first presented at the 1st Academy Awards in 1929) – is given annually by the Board of Governors of the Academy of M ...

Oscar presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS, often pronounced ; also known as simply the Academy or the Motion Picture Academy) is a professional honorary organization with the stated goal of advancing the arts and sciences of motion ...

in 1960, in recognition of "his pioneering inventions which brought sound to the motion picture".

* Honored February 8, 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a historic landmark which consists of more than 2,700 five-pointed terrazzo and brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in Hollywood, Calif ...

.

* DeVry University was originally named the De Forest Training School by its founder Dr. Herman A. De Vry, who was a friend and colleague of de Forest.

Personal life

Marriages

De Forest was married four times, with the first three marriages ending in divorce:

* Lucille Sheardown in February 1906. Divorced before the end of the year.

* Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (1883–1971) on February 14, 1908. They had a daughter, Harriet, but were separated by 1909 and divorced in 1912.

* Mary Mayo (1892–1957) in December 1912. According to census records, in 1920 they were living with their infant daughter, Deena (born ca. 1919); divorced October 5, 1930 (per ''Los Angeles Times''). Mayo died December 30, 1957 in a fire in Los Angeles.

*

De Forest was married four times, with the first three marriages ending in divorce:

* Lucille Sheardown in February 1906. Divorced before the end of the year.

* Nora Stanton Blatch Barney (1883–1971) on February 14, 1908. They had a daughter, Harriet, but were separated by 1909 and divorced in 1912.

* Mary Mayo (1892–1957) in December 1912. According to census records, in 1920 they were living with their infant daughter, Deena (born ca. 1919); divorced October 5, 1930 (per ''Los Angeles Times''). Mayo died December 30, 1957 in a fire in Los Angeles.

* Marie Mosquini

Marie Mosquini (born Marie de Esy; December 3, 1899 – February 21, 1983) was an American film actress.

Biography

Born in 1899, Mosquini appeared in more than 200 silent films between 1917 and 1929. After leaving high school she became the res ...

(1899–1983) on October 10, 1930; Mosquini was a silent film actress, and they remained married until his death in 1961.

Politics

De Forest was a conservative Republican and ferventanti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and the ...

and anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers wer ...

. In 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, he voted for Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, but later came to resent him, calling Roosevelt America's "first Fascist president". In 1949, he "sent letters to all members of Congress urging them to vote against socialized medicine

Socialized medicine is a term used in the United States to describe and discuss systems of universal health care—medical and hospital care for all by means of government regulation of health care and subsidies derived from taxation. Because of ...

, federally subsidized housing, and an excess profits tax". In 1952, he wrote to the newly elected Vice President Richard Nixon