League of Saint George on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The League of St George is a

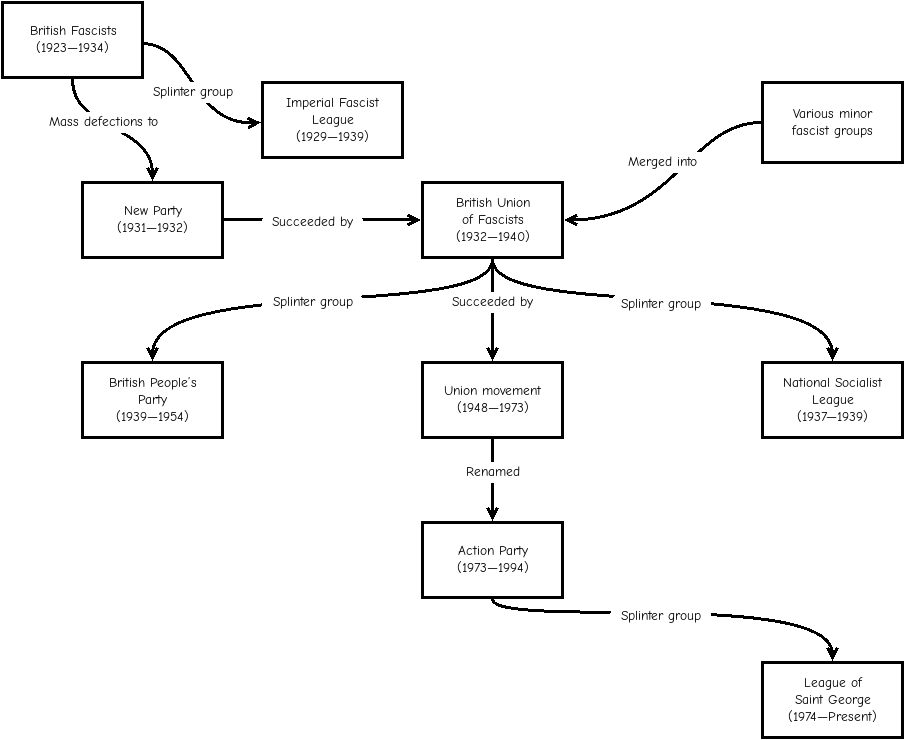

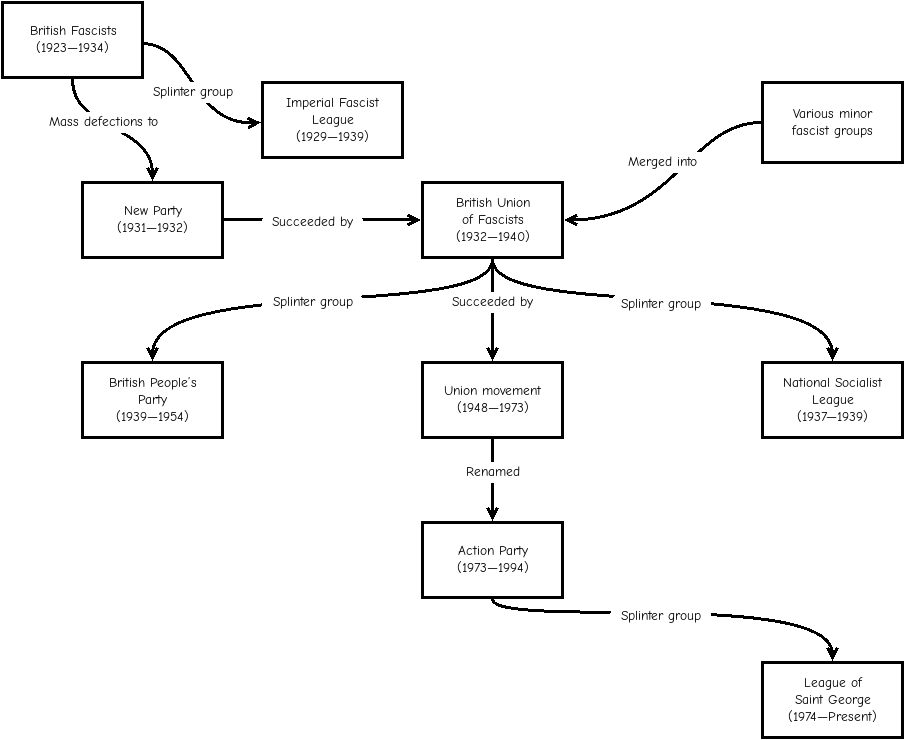

The League was formed around 1974 as a political club by Keith Thompson and Mike Griffin as a breakaway from the Action Party, founded by British

The League was formed around 1974 as a political club by Keith Thompson and Mike Griffin as a breakaway from the Action Party, founded by British

The League of Saint George website

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzEG1njUfH0 Channel 4 documentary broadcast in 1984 showing archive footage of members of the League of Saint George in attendance at neo-fascist rallies in Diksmuide, Belgium] {{UK far right 1974 establishments in the United Kingdom Neo-fascist organizations Political organisations based in the United Kingdom Fascism in the United Kingdom Far-right politics in the United Kingdom

neo-Fascist

Neo-fascism is a post-World War II far-right ideology that includes significant elements of fascism. Neo-fascism usually includes ultranationalism, racial supremacy, populism, authoritarianism, nativism, xenophobia, and anti-immigration sent ...

organisation based in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. It has defined itself as a "non-party, non-sectarian political club" and, whilst forging alliances with different groups, has eschewed close links with other extremist political parties.

History

The League was formed around 1974 as a political club by Keith Thompson and Mike Griffin as a breakaway from the Action Party, founded by British

The League was formed around 1974 as a political club by Keith Thompson and Mike Griffin as a breakaway from the Action Party, founded by British fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

. The League sought to continue what it saw as a purer form of the ideas of Mosley than those offered by then leader Jeffrey Hamm

Edward Jeffrey Hamm (15 September 1915 – 4 May 1992) was a leading British fascist and supporter of Oswald Mosley. Although a minor figure in Mosley's prewar British Union of Fascists, Hamm became a leading figure after the Second World War a ...

. In the 1970s the League became a political home for the more intellectual adherents of "Neo-Nazi" ideology, particularly those who wanted a united Europe with a European-derived population, a continuation of Mosley's Europe a Nation

Europe a Nation was a policy developed by the British fascist politician Oswald Mosley as the cornerstone of his Union Movement. It called for the integration of Europe into a single political entity. Although the idea failed to gain widespread ...

policy. Alongside this the League also followed Mosley's lead in endorsing Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

, something of a change from their contemporaries in the British far right who reserved their support for Ulster loyalism

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

. The League was never intended to be a political party, but more of a social, intellectual, and cultural organization, albeit with the ultimate political aim of promoting European people and their culture. Intended as an exclusive club for what were seen as the leading minds on the British far right, its membership tended to be restricted to around 50–100 members. Indeed, membership of the League was restricted to those invited to join only.Peter Barberis, John McHugh, Mike Tyldesley, ''Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations: Parties, Groups and Movements of the 20th Century'', Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000, p. 185

The group often had a torrid relationship with the far right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

parties, and indeed the National Front barred its members from joining the League in 1977. Around this time '' Spearhead'' even included articles claiming that the League was in fact a cult

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

dominated by clandestine leaders, secret oaths and profane initiation ceremonies. Nonetheless, individual members maintained ties to both organisations, with some contributing to both ''Spearhead'' and ''The League Review''. Similarly the British Movement

The British Movement (BM), later called the British National Socialist Movement (BNSM), is a British neo-Nazi organisation founded by Colin Jordan in 1968. It grew out of the National Socialist Movement (NSM), which was founded in 1962. Frequentl ...

, which had originally co-operated with the League, eventually severed its ties over the Northern Irish issue. ''The Enemy Within'' is an account of the League of St George written by a former member, the cartoonist Robert Edwards, who founded the pro-Mosley ''European Action'' UK pressure group in 2005.

International contacts

Adopting the emblem of the Arrow Cross, the League sought to forge links with like-minded groups inEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, and took part in international neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

rallies at Diksmuide

(; french: Dixmude, ; vls, Diksmude) is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders. The municipality comprises the city of proper and the former communes of Beerst, Esen, Kaaskerke, Keiem, Lampernisse, Leke, N ...

in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, where it forged links with the ''Vlaamse Militanten Orde

The Order of Flemish Militants ( nl, Vlaamse Militanten Orde or VMO) – originally the Flemish Militants Organisation (''Vlaamse Militanten Organisatie'') – was a Flanders, Flemish nationalism, nationalist activist group in Belgium defending fa ...

'' and the National States' Rights Party

The National States' Rights Party was a white supremacist political party that briefly played a minor role in the politics of the United States.

Foundation

Founded in 1958 in Knoxville, Tennessee, by Edward Reed Fields, a 26-year-old chiropractor ...

. Eschewing the route of electoral politics, the League instead sought to set itself up as an umbrella group for National Socialists

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

of any affiliation, although the League did work closely with first the British Movement

The British Movement (BM), later called the British National Socialist Movement (BNSM), is a British neo-Nazi organisation founded by Colin Jordan in 1968. It grew out of the National Socialist Movement (NSM), which was founded in 1962. Frequentl ...

and then the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

when it was founded (with Thompson and John Graeme Wood attending the party's inaugural meeting while claiming to speak for the League).

Steve Brady, a former activist in the short-lived National Party (and who retained close links to the Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalism, Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and Timeline of Ulster Defence Association act ...

despite the League's avowed support for Irish republicanism), was appointed International Liaison Officer in 1978 and helped to oversee the development of links with groups internationally such as the Faisceaux Nationalistes Européens of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, founded by Mark Fredriksen Mark Fredriksen (18 November 1936 – 25 August 2011) was a French extreme right figure and the founder, in 1966, of the neo-Nazi '' Fédération d'action nationaliste et européenne''.

Biography

Fredriksen co-edited ''Notre Europe'', which was ...

, and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

's Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari

The Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari ( en, Armed Revolutionary Nuclei), abbreviated NAR, was an Italian terrorist neo-fascist militant organization active during the Years of Lead from 1977 to November 1981. It committed 33 murders in four years, an ...

(NAR). Brady also wrote a column in ''League Review'', under the nom-de-plume Heimdall

In Norse mythology, Heimdall (from Old Norse Heimdallr) is a god who keeps watch for invaders and the onset of Ragnarök from his dwelling Himinbjörg, where the burning rainbow bridge Bifröst meets the sky. He is attested as possessing for ...

. The group also gained support in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

amongst some leading supporters of the Herstigte Nasionale Party

The Herstigte Nasionale Party (Reconstituted National Party) is a List of political parties in South Africa, South African political party which was formed as a Far-right politics, far-right splinter group of the now defunct National Party (So ...

who were responsible for funding the League during the early 1980s.

'Safehousing'

The League went into hiatus in the early 1980s after an episode ofITV

ITV or iTV may refer to:

ITV

*Independent Television (ITV), a British television network, consisting of:

** ITV (TV network), a free-to-air national commercial television network covering the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islan ...

current affairs show ''World in Action

''World in Action'' was a British investigative current affairs programme made by Granada Television for ITV from 7 January 1963 until 7 December 1998. Its campaigning journalism frequently had a major impact on events of the day. Its product ...

'' exposed its attempts to set up safe houses for suspected Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

terrorists, based on information given by Ray Hill, who had been active in the League.

Subsequent activities

Following these revelations the group became less active, but did not close down altogether. Its magazine, ''The National Review'', received some attention in far-right circles in 1986 whenColin Jordan

John Colin Campbell Jordan (19 June 1923 – 9 April 2009) was a leading figure in post-war neo-Nazism in Great Britain. In the far-right circles of the 1960s, Jordan represented the most explicitly "Nazi" inclination in his open use of the st ...

published an article calling for the development of an underground struggle. This article was credited with attempts to revive the British Movement

The British Movement (BM), later called the British National Socialist Movement (BNSM), is a British neo-Nazi organisation founded by Colin Jordan in 1968. It grew out of the National Socialist Movement (NSM), which was founded in 1962. Frequentl ...

and to set up other groups to carry out Jordan's ideas.

In 1996 it was alleged in ''Searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a particular direc ...

'' that members of the League had recruited mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

for a mission in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

organised by Constand Viljoen

General Constand Laubscher Viljoen, (28 October 1933 – 3 April 2020) was a South African military commander and politician. He co-founded the Afrikaner Volksfront (Afrikaner People's Front) and later founded the Freedom Front (now F ...

with the aim of assassinating the country's leaders and damaging its infrastructure. Ultimately the plan was foiled by the South African secret service and by a change in strategy by Viljoen, who abandoned his Afrikaner Volksfront

The Afrikaner Volksfront (AVF; ) was a separatist umbrella organisation uniting a number of right-wing Afrikaner organisations in South Africa in the early 1990s.

History

The AVF was formed by General Constand Viljoen and three other gene ...

in order to lead the Freedom Front

The Freedom Front Plus (FF Plus; af, Vryheidsfront Plus, ''VF Plus'') is a right-wing political party in South Africa that was formed (as the Freedom Front) in 1994. It is led by Pieter Groenewald. Its current stated policy positions include ...

.

It continues to exist under other leadership to this day. Previously publishing a regular monthly magazine, ''The League Review'', which had a comparatively wide European readership, it now publishes a quarterly journal, ''The League Sentinel''.

The group was featured in Bill Buford

Bill Buford (born 1954) is an American author and journalist. Buford is the author of the books ''Among the Thugs'' and ''Heat: An Amateur's Adventures as Kitchen Slave, Line Cook, Pasta-Maker, and Apprentice to a Dante-Quoting Butcher in Tuscan ...

's ''Among the Thugs

''Among the Thugs: The Experience, and the Seduction, of Crowd Violence'' is a 1990 work of journalism by American writer Bill Buford documenting football hooliganism in the United Kingdom.

Buford, who lived in the UK at the time, became interest ...

'' where the author commented to a member that his ideas of leaving urban life and returning to the soil recalled those of the Pol Pot

Pol Pot; (born Saloth Sâr;; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian revolutionary, dictator, and politician who ruled Cambodia as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea between 1976 and 1979. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist a ...

and the Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

.

Members

Leading members of the League have includedDagenham

Dagenham () is a town in East London, England, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Dagenham is centred east of Charing Cross.

It was historically a rural parish in the Becontree Hundred of Essex, stretching from Hainault Forest ...

-based John Harrison, millionaire Robin Rushton, former Mosley's Union Movement

The Union Movement (UM) was a far-right political party founded in the United Kingdom by Oswald Mosley. Before the Second World War, Mosley's British Union of Fascists (BUF) had wanted to concentrate trade within the British Empire, but the Uni ...

member, speaker and election candidate Keith Thompson, Mike Griffin, and Roger Clare, who has also been active in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. Ian Souter Clarence, the former head of Column 88

Column 88 was a neo-Nazi paramilitary organisation based in the United Kingdom. It was formed in the early 1970s, and disbanded in the early 1980s. The members of Column 88 undertook military training under the supervision of a former Royal Marine ...

, was a member, while both publisher Anthony Hancock and National Front and National Party veteran Denis Pirie

Denis Pirie is a veteran of the British far right scene who took a leading role in a number of movements.

He began his career as a member of the 1960s British National Party and was appointed a member of the party's national council not long afte ...

were also closely associated with the group.

Media coverage

An article by Ian Cobain in ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' dated 24 November 2016 reported that the League of St George of today is mainly active in publishing and distributing fascist books. The League's publishing arm is Steven Books.

In popular culture

In 2013, a theatrical production and musical called ''League of St George'' based on "the fascist brotherhood of the League of St George" toured the UK including theEdinburgh Festival Fringe

The Edinburgh Festival Fringe (also referred to as The Fringe, Edinburgh Fringe, or Edinburgh Fringe Festival) is the world's largest arts and media festival, which in 2019 spanned 25 days and featured more than 59,600 performances of 3,841 dif ...

, the Corbett Theatre in Loughton

Loughton () is a town and civil parish in the Epping Forest District of Essex. Part of the metropolitan and urban area of London, the town borders Chingford, Waltham Abbey, Theydon Bois, Chigwell and Buckhurst Hill, and is northeast of Chari ...

, Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

and the Hope Theatre in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

.

References

Bibliography

* R. Hill & A. Bell, ''The Other Face of Terror- Inside Europe’s Neo-Nazi Network'', London: Collins, 1988External links

The League of Saint George website

* [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lzEG1njUfH0 Channel 4 documentary broadcast in 1984 showing archive footage of members of the League of Saint George in attendance at neo-fascist rallies in Diksmuide, Belgium] {{UK far right 1974 establishments in the United Kingdom Neo-fascist organizations Political organisations based in the United Kingdom Fascism in the United Kingdom Far-right politics in the United Kingdom