L. Forbes Winslow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lyttelton Stewart Forbes Winslow MRCP (31 January 1844 – 8 June 1913) was a British

/ref> He also appeared in many civil actions.Winslow's obituary in ''

Winslow managed his father's asylums after his death in 1874, but these were removed from his control following a family feud, so he turned his attention to forensic work. Also in 1874 he changed his surname to Forbes-Winslow.

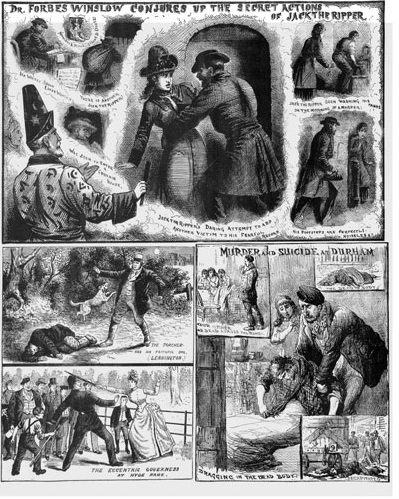

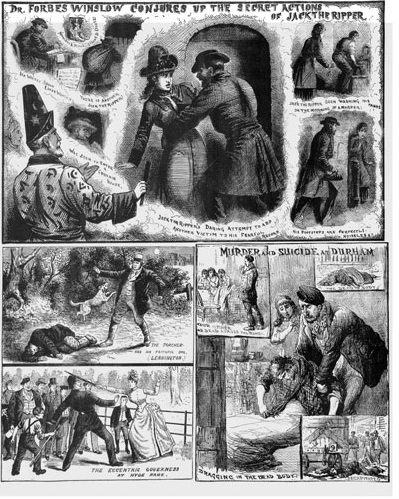

In 1888, with a little manipulation of the evidence, Winslow came to believe he knew the identity of

Winslow managed his father's asylums after his death in 1874, but these were removed from his control following a family feud, so he turned his attention to forensic work. Also in 1874 he changed his surname to Forbes-Winslow.

In 1888, with a little manipulation of the evidence, Winslow came to believe he knew the identity of

on Casebook: Jack the Ripper website Winslow's suspect was Canadian G. Wentworth Smith, who had come to London to work for the Toronto Trust Society, and who lodged with a Mr and Mrs Callaghan at 27 Sun Street,

His older brother was the Revd Forbes Edward Winslow, the vicar of

His older brother was the Revd Forbes Edward Winslow, the vicar of

Letter_of_Forbes_Winslow_to_actor_Henry_Irving

_(1879).html" ;"title="Henry Irving">Letter of Forbes Winslow to actor Henry Irving

(1879)">Henry Irving">Letter of Forbes Winslow to actor Henry Irving

(1879)br>Knows "Jack the Ripper"; He Is Hopelessly Insane, Says Dr. Forbes Winslow of London. Confined In An English Asylum – He Was a Medical Student, and Religious Mania Caused Him to Butcher the Women of the Streets.

''

"Murderers I Have Met," By Dr. Forbes L. Winslow; Famous English Authority on Insanity Writes Interesting Recollections of Trials in Which He Took Part as an Expert, Including the Hannigan Case in New York.

''

''In An Asylum Garden'' – biography of Forbes Winslow

{{DEFAULTSORT:Winslow, L. Forbes 1844 births 1913 deaths Jack the Ripper British psychiatrists English psychiatrists Alumni of Trinity College, Oxford History of mental health in the United Kingdom Alumni of Downing College, Cambridge Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers People educated at Rugby School English cricketers

psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry, the branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, study, and treatment of mental disorders. Psychiatrists are physicians and evaluate patients to determine whether their sy ...

famous for his involvement in the Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

and Georgina Weldon

Georgina Weldon (née Thomas; 24 May 1837 – 11 January 1914) was a British litigant and amateur soprano of the Victorian era.

Early years

She was born at Tooting Lodge, Clapham Common in 1837, one of seven children and the oldest daughter bo ...

cases during the late Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

.

Career

Born inMarylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An Civil parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish and latterly a ...

in London, the son of psychiatrist Forbes Benignus Winslow and Susan Winslow née Holt, Winslow was possibly the most controversial psychiatrist of his time. As a boy he was brought up in lunatic asylum

The lunatic asylum (or insane asylum) was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

The fall of the lunatic asylum and its eventual replacement by modern psychiatric hospitals explains the rise of organized, institutional psychiatr ...

s owned by his father, and was educated at Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up ...

and Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, often referred to simply as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and one of th ...

, transferring to Downing College

Downing College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge and currently has around 650 students. Founded in 1800, it was the only college to be added to Cambridge University between 1596 and 1869, and is often described as the olde ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

after four terms, where he took the MB degree in 1870. He was also a DCL(1873) of Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

of Cambridge University. A keen cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

er, Winslow captained the Downing College XI. In July 1864 he was a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket retaining considerable global influence ...

(MCC) team which played against South Wales, in which team was W. G. Grace

William Gilbert Grace (18 July 1848 – 23 October 1915) was an English amateur cricketer who was important in the development of the sport and is widely considered one of its greatest players. He played first-class cricket for a record-equal ...

.

In 1871 he was appointed a Member of the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of physicians by examination. Founded by royal charter from King Henry VIII in 1 ...

(MRCP). He spent his medical career in an attempt to persuade the courts that crime and alcoholism were the result of mental instability. His attempt in 1878 to have Mrs Georgina Weldon

Georgina Weldon (née Thomas; 24 May 1837 – 11 January 1914) was a British litigant and amateur soprano of the Victorian era.

Early years

She was born at Tooting Lodge, Clapham Common in 1837, one of seven children and the oldest daughter bo ...

committed as a lunatic at the instigation of her estranged husband William Weldon resulted in one of the most notorious court cases of the nineteenth century. The public notoriety the Weldon case caused earned him the displeasure of the medical establishment, which continued even after his death.

He became an adherent of the benefits of hypnotism in dealing with psychiatric

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders. These include various maladaptations related to mood, behaviour, cognition, and perceptions. See glossary of psychiatry.

Initial psy ...

cases. He took an active role in securing a reprieve for the four people sentenced to death for the murder by starvation of Mrs. Staunton at Penge in 1877. In 1878 he inquired into the mental condition of the Rev. Mr. Dodwell, who had shot at Sir George Jessel, the Master of the Rolls

The Keeper or Master of the Rolls and Records of the Chancery of England, known as the Master of the Rolls, is the President of the Court of Appeal (England and Wales)#Civil Division, Civil Division of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales a ...

. Other trials in which Winslow was involved were those of Percy Lefroy Mapleton

Percy Lefroy Mapleton (also known as Percy Mapleton Lefroy; 23 February 1860 – 29 November 1881) was a British journalist and murderer. He was the British "railway murderer" of 1881. He is important in the history of forensics and policing a ...

, convicted of the murder on the Brighton line; that of Florence Maybrick

Florence Elizabeth Chandler Maybrick (3 September 1862 – 23 October 1941) was an American woman convicted in the United Kingdom of murdering her husband, cotton merchant James Maybrick.

Early life

Florence Maybrick was born Florence Elizabet ...

, and that of Amelia Dyer

Amelia Elizabeth Dyer (née Hobley; 1836 – 10 June 1896) was an English serial killer who murdered infants in her care over a thirty-year period during the Victorian era of the United Kingdom.

, the Reading baby farmer.FMonika Sing-Leeull text of ''Recollections of Forty Years'' by L. Forbes Winslow Published by John Ouseley Ltd, London (1910)/ref> He also appeared in many civil actions.Winslow's obituary in ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' 9 June 1913

Jack the Ripper

Winslow managed his father's asylums after his death in 1874, but these were removed from his control following a family feud, so he turned his attention to forensic work. Also in 1874 he changed his surname to Forbes-Winslow.

In 1888, with a little manipulation of the evidence, Winslow came to believe he knew the identity of

Winslow managed his father's asylums after his death in 1874, but these were removed from his control following a family feud, so he turned his attention to forensic work. Also in 1874 he changed his surname to Forbes-Winslow.

In 1888, with a little manipulation of the evidence, Winslow came to believe he knew the identity of Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

, and believed that if he was given a team of six Police Constables he could catch the murderer.Dr. Lyttleton Forbes Winslowon Casebook: Jack the Ripper website Winslow's suspect was Canadian G. Wentworth Smith, who had come to London to work for the Toronto Trust Society, and who lodged with a Mr and Mrs Callaghan at 27 Sun Street,

Finsbury Square

Finsbury Square is a square in Finsbury in central London which includes a six-rink grass bowling green. It was developed in 1777 on the site of a previous area of green space to the north of the City of London known as Finsbury Fields, in the pa ...

. Mr Callaghan became suspicious of Smith when he was heard saying that all prostitutes should be drowned. Smith also talked and moaned to himself, and kept three loaded revolvers hidden in a chest of drawers. Callaghan went to Winslow to express his suspicions, and he in turn contacted the police, who fully investigated his theory and showed it to be without foundation. Nevertheless, convinced that he was correct, for many years Winslow declared his theory at every chance, and claimed that his actions were responsible for forcing Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in and around the impoverished Whitechapel district of London, England, in the autumn of 1888. In both criminal case files and the contemporaneous journalistic accounts, the killer wa ...

into abandoning murder and fleeing the country.

In his 1910 memoirs Winslow describes how he spent days and nights in Whitechapel

Whitechapel is a district in East London and the future administrative centre of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a part of the East End of London, east of Charing Cross. Part of the historic county of Middlesex, the area formed ...

: "The detectives knew me, the lodging house keepers knew me, and at last the poor creatures of the streets came to know me. In terror they rushed to me with every scrap of information which might, to my mind, be of value to me. The frightened women looked for hope in my presence. They felt reassured and welcomed me to their dens and obeyed my commands eagerly, and I found the bits of information I wanted".

When Winslow's claims about knowing the identity of the Ripper were reported in the English press Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London's ...

sent Chief Inspector

Chief inspector (Ch Insp) is a rank used in police forces which follow the British model. In countries outside Britain, it is sometimes referred to as chief inspector of police (CIP).

Usage by country Australia

The rank of chief inspector is use ...

Donald Swanson

Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson (12 August 1848 - 24 November 1924) was born at Geise, where his father operated a distillery, before the family moved in 1851 to Thurso, and was a senior police officer in the Metropolitan Police in Lond ...

to interview him. Confronted with this senior police officer, Forbes Winslow immediately began to back-pedal. He said the story printed in the newspaper was not accurate and misrepresented the entire conversation between himself and the reporter. He further stated that the reporter had tricked him into talking about the Ripper murders. In fact, Winslow had never given any information to the police with the exception of his earlier theory concerning an escaped lunatic, a theory which even Forbes Winslow abandoned.

According to Donald McCormick

George Donald King McCormick (11 December 1911 – 2 January 1998) was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonym Richard Deacon.

After working for Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, McCormick wa ...

, for a short period the police suspected Winslow of involvement in the killings because of his persistence and constant agitation in the Jack the Ripper case, and they checked on his movements at the time of the Ripper murders. He gained further publicity, and visited New York City in August 1895, to chair a meeting on lunacy at an International Medico-Legal Congress. He also appeared as an expert defence witness in some American cases involving lunacy.

Spiritualism

Winslow was the author of the 1877 pamphlet ''Spiritualistic Madness'' which identifiedspiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

as a cause of insanity

Insanity, madness, lunacy, and craziness are behaviors performed by certain abnormal mental or behavioral patterns. Insanity can be manifest as violations of societal norms, including a person or persons becoming a danger to themselves or to ...

. He wrote that many believers in spiritualism were women and victims of their own gullibility. Winslow wrote that most believers in spiritualism were insane and suffer from mental delusion

A delusion is a false fixed belief that is not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, hallucination, or some o ...

s. He affirmed that there were "nearly ten thousand uch

Uch ( pa, ;

ur, ), frequently referred to as Uch Sharīf ( pa, ;

ur, ; ''"Noble Uch"''), is a historic city in the southern part of Pakistan's Punjab province. Uch may have been founded as Alexandria on the Indus, a town founded by Alexan ...

persons in America" who had been confined in lunatic asylum

The lunatic asylum (or insane asylum) was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

The fall of the lunatic asylum and its eventual replacement by modern psychiatric hospitals explains the rise of organized, institutional psychiatr ...

s.

Personal life

His older brother was the Revd Forbes Edward Winslow, the vicar of

His older brother was the Revd Forbes Edward Winslow, the vicar of Epping Epping may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Epping, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

** Epping railway station, Sydney

* Electoral district of Epping, the corresponding seat in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

* Epping Forest, Kearns, a he ...

, while his sister, Susanna Frances, married the humorist Arthur William à Beckett

Arthur William à Beckett (25 October 1844 – 14 January 1909) was an English journalist and intellectual.

Biography

He was a younger son of Gilbert Abbott à Beckett and Mary Anne à Beckett, brother of Gilbert Arthur à Beckett and educate ...

. Forbes Winslow published his memoirs, ''Recollections of Forty Years'', in 1910, and also wrote the ''Handbook For Attendants on the Insane''. He founded the British Hospital for Mental Disorders in London, and was a lecturer on insanity at Charing Cross Hospital

Charing Cross Hospital is an acute general teaching hospital located in Hammersmith, London, United Kingdom. The present hospital was opened in 1973, although it was originally established in 1818, approximately five miles east, in central Lond ...

and was a physician to the West End Hospital and the North London Hospital for Consumption. A member of the Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket retaining considerable global influence ...

(MCC) and a Vice-President of the Psycho—Therapeutic Society, he married twice. In the 1880s, he was the owner of the famous progenitor of the modern English Mastiff

The English Mastiff, or simply the Mastiff, is a British dog breed of very large size. Likely descended from the ancient Alaunt and Pugnaces Britanniae, with a significant input from the Alpine Mastiff in the 19th century. Distinguished by its e ...

, Ch. Crown Prince.

Winslow died at his home in Devonshire Street

Devonshire Street is a street in the City of Westminster, London. Adjoining Harley Street, it is known for the number of medical establishments it contains.

The street is named after the 5th Duke of Devonshire, who was related to the ground l ...

, London, of a heart attack, aged 69. He left a widow, three sons and a daughter, Dulcie Sylvia, who, in 1906, married Roland St John Braddell (1880–1966).

Winslow appears as the central figure in the 2003 novel ''A Handbook for Attendants on the Insane''. It has now been republished in a revised new edition as ''The Revelation of Jack the Ripper'' by Alan Scarfe

Alan John Scarfe (born 8 June 1946) is a British–Canadian actor, stage director and author. He is a former Associate Director of the Stratford Festival (1976–77) and the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool (1967–68). He won the 1985 Genie A ...

.smarthousebooks.com

Publications

*''Obscure Diseases of the Mind'' (1866) *''Recollections of Forty Years'' (1910) *''Handbook For Attendants On The Insane'' (1877) *''Spiritualistic Madness'' (1877) *''Mad Humanity: Its Forms Apparent and Obscure" (1898)'' *''Doctor Forbes Winslow: Defender of the Insane'' Capella (2000)References

External links

Letter_of_Forbes_Winslow_to_actor_Henry_Irving

_(1879).html" ;"title="Henry Irving">Letter of Forbes Winslow to actor Henry Irving

(1879)">Henry Irving">Letter of Forbes Winslow to actor Henry Irving

(1879)br>Knows "Jack the Ripper"; He Is Hopelessly Insane, Says Dr. Forbes Winslow of London. Confined In An English Asylum – He Was a Medical Student, and Religious Mania Caused Him to Butcher the Women of the Streets.

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' 1 September 1895"Murderers I Have Met," By Dr. Forbes L. Winslow; Famous English Authority on Insanity Writes Interesting Recollections of Trials in Which He Took Part as an Expert, Including the Hannigan Case in New York.

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' 25 June 1911''In An Asylum Garden'' – biography of Forbes Winslow

{{DEFAULTSORT:Winslow, L. Forbes 1844 births 1913 deaths Jack the Ripper British psychiatrists English psychiatrists Alumni of Trinity College, Oxford History of mental health in the United Kingdom Alumni of Downing College, Cambridge Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers People educated at Rugby School English cricketers