Know Nothings on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Know Nothing party was a nativist

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in

In the spring of 1855, Know Nothing candidate Levi Boone was elected mayor of Chicago and barred all immigrants from city jobs. Abraham Lincoln was strongly opposed to the principles of the Know Nothing movement, but did not denounce it publicly because he needed the votes of its membership to form a successful anti-slavery coalition in Illinois. Ohio was the only state where the party gained strength in 1855. Their Ohio success seems to have come from winning over immigrants, especially German-American Lutherans and Scots-Irish Presbyterians, both hostile to Catholicism. In Alabama, Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, discontented Democrats and other political outsiders who favored state aid to build more railroads. Virginia attracted national attention in its tempestuous 1855 gubernatorial election. Democrat

In the spring of 1855, Know Nothing candidate Levi Boone was elected mayor of Chicago and barred all immigrants from city jobs. Abraham Lincoln was strongly opposed to the principles of the Know Nothing movement, but did not denounce it publicly because he needed the votes of its membership to form a successful anti-slavery coalition in Illinois. Ohio was the only state where the party gained strength in 1855. Their Ohio success seems to have come from winning over immigrants, especially German-American Lutherans and Scots-Irish Presbyterians, both hostile to Catholicism. In Alabama, Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, discontented Democrats and other political outsiders who favored state aid to build more railroads. Virginia attracted national attention in its tempestuous 1855 gubernatorial election. Democrat

Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them. On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "

Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them. On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "

The party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the

The party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the

online excerpt

* Baker, Jean H. (1977), ''Ambivalent Americans: The Know-Nothing Party in Maryland'', Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. * Baum, Dale. "Know-Nothingism and the Republican Majority in Massachusetts: The Political Realignment of the 1850s." ''Journal of American History'' 64 (1977–78): 959–86

in JSTOR

* Baum, Dale. ''The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848–1876'' (1984) * Bennett, David H. ''The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History'' (1988

online

* Billington, Ray A. ''The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism'' (1938), standard scholarly survey

online

* Bladek, John David. "'Virginia Is Middle Ground': the Know Nothing Party and the Virginia Gubernatorial Election of 1855." ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' 1998 106(1): 35–70

in JSTOR

* Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics." ''Smithsonian Magazine'' (2017), heavily illustrated with editorial cartoons

online

* Cheathem, Mark R. "'I Shall Persevere in the Cause of Truth': Andrew Jackson Donelson and the Election of 1856". ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly'' 2003 62(3): 218–237. Donelson was Andrew Jackson's nephew and K–N nominee for Vice President * Dash, Mark. "New Light on the Dark Lantern: the Initiation Rites and Ceremonies of a Know-Nothing Lodge in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania" ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 2003 127(1): 89–100. * Desmond, Humphrey J. ''The Know-Nothing Party'' (1905

online

* Gienapp, William E. "Nativism and the Creation of a Republican Majority in the North before the Civil War," ''Journal of American History'', Vol. 72, No. 3 (Dec., 1985), pp. 529–55

in JSTOR

* Gienapp, William E. ''The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856'' (1978), detailed statistical study, state-by-state * Gillespie, J. David. ''Challengers To Duopoly : Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics.'' Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2012. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 4 Dec. 2014. * Gleeson, David T. ''The Irish in the South, 1815–1877'' Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. * Haebler, Peter. "Nativist Riots in Manchester: An Episode of Know-Nothingism in New Hampshire." ''Historical New Hampshire'' 39 (1985): 121-37. * Holt, Michael F. ''The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party'' (1999) * Holt, Michael F. ''Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln'' (1992) * Holt, Michael F. "The Antimasonic and Know Nothing Parties", in Arthur Schlesinger Jr., ed., ''History of United States Political Parties'' (1973), I, 575–620. * Hurt, Payton. "The Rise and Fall of the 'Know Nothings' in California," ''California Historical Society Quarterly'' 9 (March and June 1930). * Kadir, Djelal. "Agnotology and the Know-Nothing Party: Then and Now." ''Review of International American Studies'' 10.1 (2017): 117–131

online

* Levine, Bruce. "Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-nothing Party" ''Journal of American History'' 2001 88(2): 455–488

in JSTOR

* McGreevey, John T. ''Catholicism and American Freedom: A History'' (W. W. Norton, 2003) * Maizlish, Stephen E. "The Meaning of Nativism and the Crisis of the Union: The Know-Nothing Movement in the Antebellum North." in William Gienapp, ed. ''Essays on American Antebellum Politics, 1840–1860'' (1982) pp. 166–98 * Melton, Tracy Matthew. ''Hanging Henry Gambrill: The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, 1854–1860''. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society (2005). * Mulkern, John R. ''The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People's Movement''. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1990

excerpt

* Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing, 1852–1857'' (1947), overall political survey of era * Overdyke, W. Darrell. ''The Know-Nothing Party in the South'' (1950) * Ramet, Sabrina P., and Christine M. Hassenstab. "The Know Nothing Party: Three Theories about its Rise and Demise." ''Politics and Religion'' 6.3 (2013): 570–595. * Parmet, Robert D. "Connecticut's Know-Nothings: A Profile," ''Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin'' (1966), 31 #3, pp. 84–90 * Rice, Philip Morrison. "The Know-Nothing Party in Virginia, 1854–1856." ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' (1947): 61–75

in JSTOR

* Roseboom, Eugene H. "Salmon P. Chase and the Know Nothings." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 25.3 (1938): 335-350

online

* Scisco, Louis Dow. ''Political Nativism in New York State'' (1901

full text online

pp. 84–202 * Taylor, Steven. "Progressive Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts" ''Historical Journal of Massachusetts'' (2000) 28#

online

* Voss-Hubbard, Mark. ''Beyond Party: Cultures of Antipartisanship in Northern Politics before the Civil War'' (2002) * Wilentz, Sean. ''The Rise of American Democracy.'' (2005);

''The Sons of the Sires: A History of the Rise, Progress, and Destiny of the American Party''

Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1855. Work by K–N activist. * Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics." ''Smithsonian Magazine'' (2017), heavily illustrated with editorial cartoons

online

* Busey, Samuel Clagett (1856)

''Immigration: Its Evils and Consequences''

* Carroll, Anna Ella (1856)

''The Great American Battle: Or, The Contest Between Christianity and Political Romanism''

* Fillmore, Millard; Frank H. Severance (ed.)(1907)

''Millard Fillmore Papers''

* One of Them

''The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855''

New York: J.C. Derby, 1855. ** Bond, Thomas E

"The 'Know Nothings

from ''The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855''. New York: J. C. Derby, 1855; pp. 54–63.

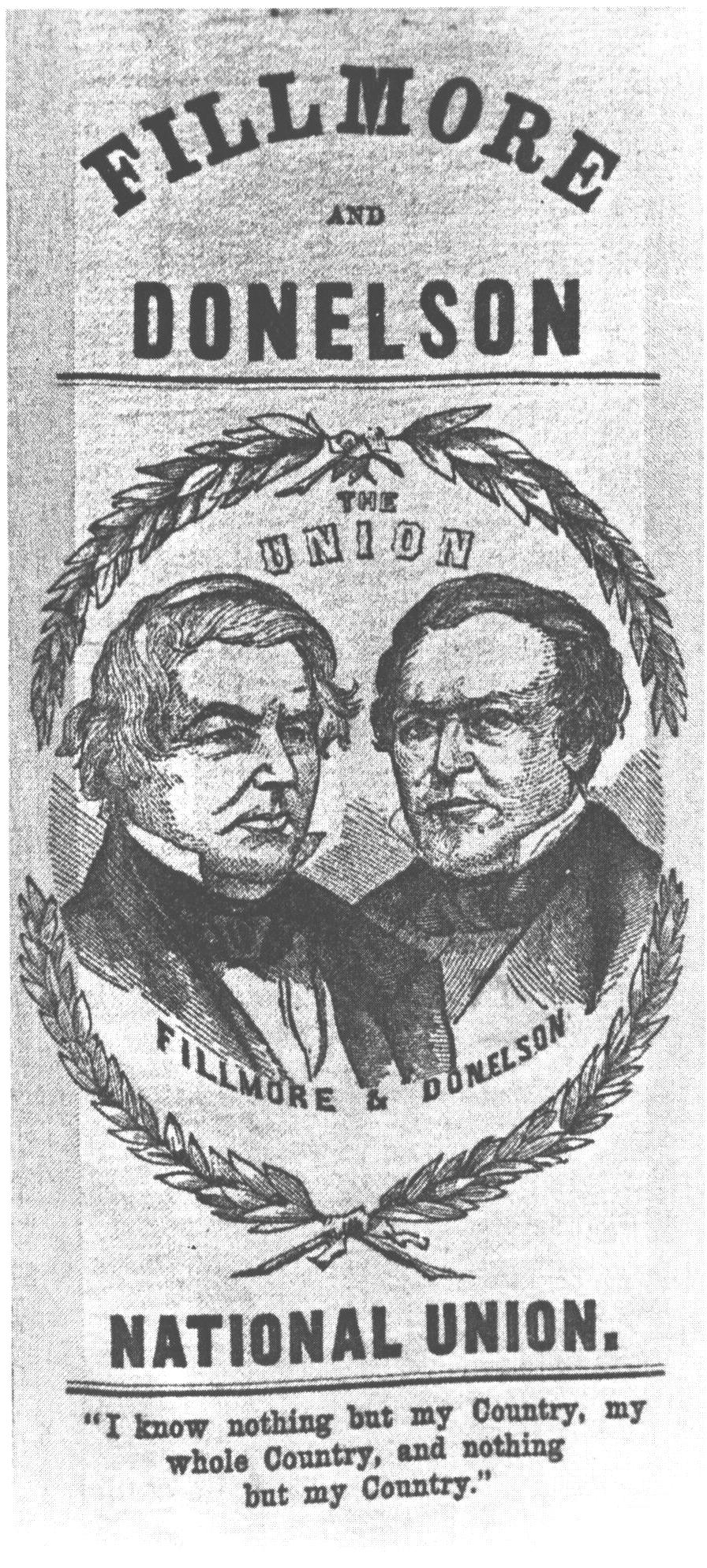

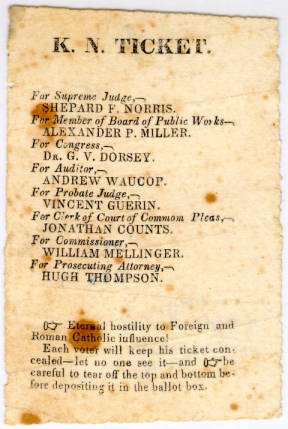

Nativism in the 1856 Presidential Election

* *

* {{authority control American nationalist parties American nationalists Anti-Catholicism in the United States Anti-Catholic organizations Anti-German sentiment in the United States Anti-immigration politics in the United States Anti-Irish sentiment Defunct American political movements Defunct far-right political parties in the United States 1850s in the United States Political parties in the United States Right-wing populism in the United States Conservatism in the United States

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". Members of the movement were required to say "I know nothing" whenever they were asked about its specifics by outsiders, providing the group with its colloquial name.

Supporters of the Know Nothing movement believed that an alleged " Romanist" conspiracy by Catholics to subvert civil and religious liberty

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedo ...

in the United States was being hatched. Therefore, they sought to politically organize native-born Protestants in defense of their traditional religious and political values. The Know Nothing movement is remembered for this theme because Protestants feared that Catholic priests and bishops would control a large bloc of voters. In most places, the ideology and influence of the Know Nothing movement lasted only one or two years before it disintegrated due to weak and inexperienced local leaders, a lack of publicly proclaimed national leaders, and a deep split over the issue of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. In the South, the party did not emphasize anti-Catholicism as frequently as it emphasized it in the North and it stressed a neutral position on slavery, but it became the main alternative to the dominant Democratic Party.

Know Nothings are occasionally referred to as an antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

movement due to their zealous xenophobia and religious bigotry; however, the movement was not openly hostile towards Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

because its members and supporters believed that Jews did not allow "their religious feelings to interfere with their political views." The Know Nothing Party, prioritizing a zealous disdain for Irish Catholic immigrants, reportedly "had nothing to say about Jews", according to historian Hasia Diner

Hasia Diner

Hasia R. Diner is an American historian. Diner is the Paul S. and Sylvia Steinberg Professor of American Jewish History; Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, History; Director of the Goldstein-Goren Center for American Jewish Hi ...

. In New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, the virulently anti-Catholic Know Nothings supported a Jewish candidate for governor.

The Know Nothings supplemented their xenophobic views with populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

appeals. The party was progressive in its stances on "issues of labor rights and the need for more government spending" and furnished "support for an expansion of the rights of women, the regulation of industry, and support of measures which were designed to improve the status of working people." It was a forerunner of the temperance movement in the United States

The Temperance movement in the United States is a movement to curb the consumption of alcohol. It had a large influence on American politics and American society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, culminating in the prohibition of alcoh ...

. The Know Nothing movement briefly emerged as a major political party in the form of the American Party.

The collapse of the Whig Party after the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law ...

left an opening for the emergence of a new major political party in opposition to the Democratic Party. The Know Nothing movement managed to elect congressman Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

and several other individuals into office in the 1854 elections, and it subsequently coalesced into a new political party which was known as the American Party. Particularly in the South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

, the American Party served as a vehicle for politicians who opposed the Democrats. Many of the American Party's members and supporters also hoped that it would stake out a middle ground between the pro-slavery positions of Democratic politicians and the radical anti-slavery positions of the rapidly emerging Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. The American Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

in the 1856 presidential election, but he kept quiet about his membership in it, and he personally refrained from supporting the Know Nothing movement's activities and ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

. Fillmore received 21.5% of the popular vote in the 1856 presidential election, finishing behind the Democratic and Republican nominees. Henry Winter Davis, an active Know-Nothing, was elected on the American Party ticket to Congress from Maryland. He told Congress the un-American Irish Catholic immigrants were to blame for the recent election of Democrat James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

as president, stating:The recent election has developed in an aggravated form every evil against which the American party protested. Foreign allies have decided the government of the country -- men naturalized in thousands on the eve of the election. Again in the fierce struggle for supremacy, men have forgotten the ban which the Republic puts on the intrusion of religious influence on the political arena. These influences have brought vast multitudes of foreign-born citizens to the polls, ignorant of American interests, without American feelings, influenced by foreign sympathies, to vote on American affairs; and those votes have, in point of fact, accomplished the present result.The party entered a period of rapid decline after Fillmore's loss. In 1857 the ''

Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

'' pro-slavery decision of the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

further galvanized opposition to slavery in the North, causing many former Know Nothings to join the Republicans. The remnants of the American Party largely joined the Constitutional Union Party in 1860 and they disappeared during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

History

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

, but it played a minor role in American politics

The politics of the United States function within a framework of a constitutional federal republic and presidential system, with three distinct branches that share powers. These are: the U.S. Congress which forms the legislative branch, a b ...

until the arrival of large numbers of Irish and German Catholics in the 1840s. It then reemerged in nativist attacks on Catholic immigration. It appeared in New York City politics as early as 1843 under the banner of the American Republican Party

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP ("Grand Old Party"), is one of the Two-party system, two Major party, major contemporary political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by Abolitionism in the United Stat ...

. The movement quickly spread to nearby states using that name or Native American Party or variants of it. They succeeded in a number of local and Congressional elections, notably in 1844 in Philadelphia, where the anti-Catholic orator Lewis Charles Levin

Lewis Charles Levin (November 10, 1808 – March 14, 1860) was an American politician, newspaper editor and anti-Catholic social activist. He was one of the founders of the American Party in 1842 and served as a member of the U. S. House of Rep ...

was elected Representative from Pennsylvania's 1st district. In the early 1850s, numerous secret orders grew up, of which the Order of United Americans and the Order of the Star Spangled Banner

The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was an oath-bound secret society in New York City. It was created in 1849 by Charles B. Allen to protest the rise of Irish, Catholic, and German immigration into the United States.

To join the Orde ...

came to be the most important. They emerged in New York in the early 1850s as a secret order that quickly spread across the North, reaching non-Catholics, particularly those non-Catholics who were lower middle class or skilled workers.

The name ''Know Nothing'' originated in the semi-secret organization of the party. When a member of the party was asked about his activities, he was supposed to say, "I know nothing." Outsiders derisively called the party's members "Know Nothings", and the name stuck. In 1855, the Know Nothings first entered politics under the American Party label.

Underlying issues

The immigration of large numbers of Irish and German Catholics to the United States in the period between 1830 and 1860 made religious differences between Catholics and Protestants a political issue. Violence occasionally erupted at the polls. Protestants alleged that PopePius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

had contributed to the failure of the liberal Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europ ...

in Europe and they also alleged that he was an enemy of liberty, democracy and republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

. One Boston minister described Catholicism as "the ally of tyranny, the opponent of material prosperity, the foe of thrift, the enemy of the railroad, the caucus, and the school". These fears encouraged conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that invokes a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups, often political in motivation, when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

*

*

* The term has a nega ...

regarding papal intentions of subjugating the United States through a continuing influx of Catholics controlled by Irish bishops obedient to and personally selected by the Pope.

In 1849, an oath-bound secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence ...

, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner

The Order of the Star Spangled Banner (OSSB) was an oath-bound secret society in New York City. It was created in 1849 by Charles B. Allen to protest the rise of Irish, Catholic, and German immigration into the United States.

To join the Orde ...

, was founded by Charles B. Allen in New York City. At its inception, the Order of the Star Spangled Banner only had about 36 members. Fear of Catholic immigration caused some Protestants to become dissatisfied with the Democratic Party, whose leaders included Catholics of Irish descent in many cities. Activists formed secret groups, coordinating their votes and throwing their weight behind candidates who were sympathetic to their cause:

Rise

In the spring of 1854, the Know Nothings carried Boston and Salem, Massachusetts, and other New England cities. They swept the state of Massachusetts in the fall 1854 elections, their biggest victory. The Whig candidate for mayor of Philadelphia, editor Robert T. Conrad, was soon revealed as a Know Nothing as he promised to crack down on crime, close saloons on Sundays and only appoint native-born Americans to office—he won the election by a landslide. In Washington, D.C., Know Nothing candidateJohn T. Towers

John Thomas Towers (1811–1857) was Superintendent of Printing at the U.S. Capitol and the sixteenth Mayor of Washington City, District of Columbia, from 1854 to 1856.

Towers was born in Alexandria, D.C., in 1811 to parents who had recently a ...

defeated incumbent Mayor John Walker Maury, triggering opposition of such a high proportion that the Democrats, Whigs, and Freesoilers in the capital united as the "Anti-Know-Nothing Party". In New York, where James Harper had been elected mayor of New York City as an American Republican the previous year, the Know Nothing candidate Daniel Ullman came in third in a four-way race for governor by gathering 26% of the vote. After the 1854 elections, they exerted a large amount of political influence in Maine, Indiana, Pennsylvania, and California, but historians are unsure about the accuracy of this information due to the secrecy of the party, because all parties were in turmoil and the anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

and prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

issues overlapped with nativism in complex and confusing ways. They helped elect Stephen Palfrey Webb

Stephen Palfrey Webb (March 20, 1804 – September 29, 1879) was an American politician who served as the third and twelfth mayor of Salem, Massachusetts, and the 5th mayor of San Francisco, California.

Early life, family life, education, an ...

as mayor of San Francisco

The mayor of the City and County of San Francisco is the head of the executive branch of the San Francisco city and county government. The officeholder has the duty to enforce city laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by ...

and they also helped elect J. Neely Johnson

John Neely Johnson (August 2, 1825 – August 31, 1872) was an American lawyer and politician. He was elected as the fourth governor of California from 1856 to 1858, and later appointed justice to the Nevada Supreme Court from 1867 to 1871. As a ...

as governor of California. Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

was elected to Congress as a Know Nothing candidate, but after a few months he aligned with Republicans. A coalition of Know Nothings, Republicans and other members of Congress opposed to the Democratic Party elected Banks to the position of Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

.

The results of the 1854 elections were so favorable to the Know Nothings, up to then an informal movement with no centralized organization, that they formed officially as a political party called the American Party, which attracted many members of the by then nearly defunct Whig party as well as a significant number of Democrats. Membership in the American Party increased dramatically, from 50,000 to an estimated one million plus in a matter of months during that year.

The historian Tyler Anbinder concluded:

In San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

, a Know Nothing chapter was founded in 1854 to oppose Chinese immigration—members included a judge of the state supreme court, who ruled that no Chinese person could testify as a witness against a white man in court.

Henry Alexander Wise

Henry Alexander Wise (December 3, 1806 – September 12, 1876) was an American attorney, diplomat, politician and slave owner from Virginia. As the 33rd Governor of Virginia, Wise served as a significant figure on the path to the American Civil W ...

won by convincing state voters that Know Nothings were in bed with Northern abolitionists. With the victory by Wise, the movement began to collapse in the South.

Know Nothings scored victories in Northern state elections in 1854, winning control of the legislature in Massachusetts and polling 40% of the vote in Pennsylvania. Although most of the new immigrants lived in the North, resentment and anger against them was national and the American Party initially polled well in the South, attracting the votes of many former southern Whigs.

The party name gained wide but brief popularity. Nativism became a new American rage: Know Nothing candy, Know Nothing tea, and Know Nothing toothpicks appeared. Stagecoaches were dubbed "The Know Nothing". In Trescott, Maine, a shipowner dubbed his new 700-ton freighter ''Know Nothing.'' The party was occasionally referred to, contemporaneously, in a slightly pejorative shortening, "Knism".

Leadership and legislation

Historian John Mulkern has examined the party's success in sweeping to almost complete control of the Massachusetts legislature after its 1854 landslide victory. He finds the new party was populist and highly democratic, hostile to wealth, elites and to expertise, and deeply suspicious of outsiders, especially Catholics. The new party's voters were concentrated in the rapidly growing industrial towns, where Yankee workers faced direct competition with new Irish immigrants. Whereas the Whig Party was strongest in high income districts, the Know Nothing electorate was strongest in the poor districts. They expelled the traditional upper-class, closed, political leadership, especially the lawyers and merchants. In their stead, they elected working-class men, farmers and a large number of teachers and ministers. Replacing the moneyed elite were men who seldom owned $10,000 in property. Nationally, the new party leadership showed incomes, occupation, and social status that were about average. Few were wealthy, according to detailed historical studies of once-secret membership rosters. Fewer than 10% were unskilled workers who might come in direct competition with Irish laborers. They enlisted few farmers, but on the other hand they included many merchants and factory owners. The party's voters were by no means all native-born Americans, for it won more than a fourth of the German and British Protestants in numerous state elections. It especially appealed to Protestants such as the Lutherans, Dutch Reformed and Presbyterians.Massachusetts

The most aggressive and innovative legislation came out of Massachusetts, where the new party controlled all but three of the 400 seats—only 35 had any previous legislative experience. The Massachusetts legislature in 1855 passed a series of reforms that "burst the dam against change erected by party politics, and released a flood of reforms." Historian Stephen Taylor says that in addition to nativist legislation, "the party also distinguished itself by its opposition to slavery, support for an expansion of the rights of women, regulation of industry, and support of measures designed to improve the status of working people". It passed legislation to regulate railroads, insurance companies and public utilities. It funded free textbooks for the public schools and raised the appropriations for local libraries and for the school for the blind. Purification of Massachusetts against divisive social evils was a high priority. The legislature set up the state's first reform school for juvenile delinquents while trying to block the importation of supposedly subversive government documents and academic books from Europe. It upgraded the legal status of wives, giving them more property rights and more rights in divorce courts. It passed harsh penalties on speakeasies, gambling houses and bordellos. It passed prohibition legislation with penalties that were so stiff—such as six months in prison for serving one glass of beer—that juries refused to convict defendants. Many of the reforms were quite expensive; state spending rose 45% on top of a 50% hike in annual taxes on cities and towns. This extravagance angered the taxpayers, and few Know Nothings were reelected. The highest priority included attacks on the civil rights of Irish Catholic immigrants. After this, state courts lost the power to process applications for citizenship and public schools had to require compulsory daily reading of the Protestant Bible (which the nativists were sure would transform the Catholic children). The governor disbanded the Irish militias and replaced Irish holding state jobs with Protestants. It failed to reach the two-thirds vote needed to pass a state constitutional amendment to restrict voting and office holding to men who had resided in Massachusetts for at least 21 years. The legislature then called on Congress to raise the requirement for naturalization from five years to 21 years, but Congress never acted. The most dramatic move by the Know Nothing legislature was to appoint an investigating committee designed to prove widespread sexual immorality underway in Catholic convents. The press had a field day following the story, especially when it was discovered that the key reformer was using committee funds to pay for a prostitute. The legislature shut down its committee, ejected the reformer, and saw its investigation become a laughing stock.New Hampshire and Rhode Island

The Know Nothings scored a landslide in New Hampshire in 1855. They won 51 % of the vote, including 94% of the Free Soilers (an anti-slavery faction of Democrats), and 79% of the Whigs, plus 15% of Democrats and 24% of those who abstained in the previous election for governor the year before. In full control of the legislature, the Know Nothings enacted their entire agenda. According to Lex Renda, they battled traditionalism and promoted rapid modernization. They extended the waiting period for citizenship to slow down the growth of Irish power; they reformed the state courts. They expanded the number and power of banks; they strengthened corporations; they defeated a proposed 10-hour law that would help workers. They reformed the tax system; increased state spending on public schools; set up a system to build high schools; prohibited the sale of liquor; and they denounced the expansion of slavery in the western territories. The Whigs and Free Soil parties both collapsed in New Hampshire in 1854-55. In the 1855 fall elections the Know Nothings again swept New Hampshire against the Democrats and the small new Republican party. When the Know Nothing ("American" Party) collapsed in 1856 and merged with the Republicans, New Hampshire now had a two party system with the Republicans edging out the Democrats. The Know Nothings also dominated politics in Rhode Island, where in 1855 William W. Hoppin held the governorship and five out of every seven votes went to the party, which dominated the Rhode Island legislature. Local newspapers such as ''The Providence Journal

''The Providence Journal'', colloquially known as the ''ProJo'', is a daily newspaper serving the metropolitan area of Providence, Rhode Island, and is the largest newspaper in Rhode Island. The newspaper was first published in 1829. The newspape ...

'' fueled anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment.

Violence

Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them. On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "

Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them. On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "Bloody Monday

Bloody Monday was a series of riots on August 6, 1855, in Louisville, Kentucky, an election day, when Protestant mobs attacked Irish and German Catholic neighborhoods. These riots grew out of the bitter rivalry between the Democrats and the Nat ...

" riot was not the only violent riot between Know Nothings and Catholics in 1855. In Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, the mayoral elections of 1856, 1857, and 1858 were all marred by violence and well-founded accusations of ballot-rigging. In the coastal town of Ellsworth Maine in 1854, Know Nothings were associated with the tarring and feathering

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture and punishment used to enforce unofficial justice or revenge. It was used in feudal Europe and its colonies in the early modern period, as well as the early American frontier, mostly as a ty ...

of a Catholic priest, Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

Johannes Bapst

John Bapst (born Johannes Bapst at La Roche, Fribourg, Switzerland, 17 December 1815; died at Mount Hope, Maryland, United States, 2 November 1887) was a Swiss Jesuit missionary and educator who became the first president of Boston College.

Li ...

. They also burned down a Catholic church in Bath, Maine

Bath is a city in Sagadahoc County, Maine, in the United States. The population was 8,766 at the 2020 census. It is the county seat of Sagadahoc County, which includes one city and 10 towns. The city is popular with tourists, many drawn by its ...

.

South

In the Southern United States, the American Party was composed chiefly of ex-Whigs looking for a vehicle to fight the dominant Democratic Party and worried about both the pro-slavery extremism of the Democrats and the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican party in the North. In the South as a whole, the American Party was strongest among former Unionist Whigs. States-rightist Whigs shunned it, enabling the Democrats to win most of the South. Whigs supported the American Party because of their desire to defeat the Democrats, their unionist sentiment, their anti-immigrant attitudes and the Know Nothing neutrality on the slavery issue. David T. Gleeson notes that many Irish Catholics in the South feared that the arrival of the Know-Nothing movement portended a serious threat. He argues:The southern Irish, who had seen the dangers of Protestant bigotry in Ireland, had the distinct feeling that the Know-Nothings were an American manifestation of that phenomenon. Every migrant, no matter how settled or prosperous, also worried that this virulent strain of nativism threatened his or her hard-earned gains in the South and integration into its society. Immigrants fears were unjustified, however, because the national debate over slavery and its expansion, not nativism or anti-Catholicism, was the major reason for Know-Nothing success in the South. The southerners who supported the Know-Nothings did so, for the most part, because they thought the Democrats who favored the expansion of slavery might break up the Union.In 1855, the American Party challenged the Democrats' dominance. In Alabama, the Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, malcontented Democrats and other political misfits; they favored state aid to build more railroads. In the fierce campaign, the Democrats argued that Know Nothings could not protect slavery from Northern abolitionists. The Know Nothing American Party disintegrated soon after losing in 1855. In Virginia, the Know Nothing movement came under sharp attack from both established parties. Democrats published a 12,000-word, point-by-point denunciation of Know Nothingism. The Democrats nominated ex-Whig Henry A. Wise for governor. He denounced the "lousy, godless, Christless" Know Nothings and instead he advocated an expanded program of internal improvements. In Maryland, growing anti-immigrant sentiment fueled the party's rise. Despite the state's Catholic roots, by the 1850s about 60 percent of the population was Protestant and open to the Know Nothing's anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant appeal. On August 18, 1853, the party held its first rally in Baltimore with about 5,000 in attendance, calling for secularization of public schools, complete separation of church and state, freedom of speech, and regulating immigration. The first Know-Nothing candidate elected into office in Baltimore was Mayor Samuel Hinks in 1855. The following year, ethnic and secular conflicts fueled

riots

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targeted ...

around municipal and federal elections in Maryland with Know-Nothing–affiliated gangs clashing with Democratic-aligned gangs.

Historian Michael F. Holt argues that "Know Nothingism originally grew in the South for the same reasons it spread in the North—nativism, anti-Catholicism, and animosity toward unresponsive politicos—not because of conservative Unionism". Holt cites William B. Campbell

William Bowen Campbell (February 1, 1807 – August 19, 1867) was an American politician and soldier. He served as the 14th governor of Tennessee from 1851 to 1853, and was the state's last Whig governor. He also served four terms in the United ...

, former governor of Tennessee, who wrote in January 1855: "I have been astonished at the widespread feeling in favor of their principles—to wit, Native Americanism and anti-Catholicism—it takes everywhere". Despite this, in Louisiana and Maryland, prominent Know Nothings remained loyal to the Union. In Maryland, American Party's former governor and later senator Thomas Holliday Hicks

Thomas Holliday Hicks (September 2, 1798February 14, 1865) was a politician in the divided border-state of Maryland during the American Civil War. As governor, opposing the Democrats, his views accurately reflected the conflicting local loyalt ...

, Representative Henry Winter Davis, and Senator Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

, along with his brother, former Representative John Pendleton Kennedy

John Pendleton Kennedy (October 25, 1795 – August 18, 1870) was an American novelist, lawyer and Whig politician who served as United States Secretary of the Navy from July 26, 1852, to March 4, 1853, during the administration of President ...

, all supported the Union in a border state. Louisiana Know Nothing congressman John Edward Bouligny, a Catholic Creole, was the only member of the Louisiana congressional delegation who refused to resign his seat after the state seceded from the Union.

Louisiana

Despite the national American Party's anti-Catholicism, the Know Nothings found strong support in Louisiana, including in largely Catholic New Orleans. The Whig Party in Louisiana had a strong anti-immigrant bent, making the Native American Party the natural home for Louisiana's former Whigs. Louisiana Know Nothings were pro-slavery and anti-immigrant, but, in contrast to the national party, refused to include a religious test for membership. Instead, the Louisiana Know Nothings insisted that "loyalty to a church should not supersede loyalty to the Union." Similarly, the broader Know Nothing movement viewed Louisiana Catholics, and in particular the Creole elite who supported the American Party, as adhering to a Gallican Catholicism and therefore opposed to papal authority over matters of state.Decline

The party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the

The party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the presidential election of 1856 {{Short description, None

The following elections occurred in the year 1856.

North America

United States

* California's at-large congressional district

* 1856 New York state election

* 1856 and 1857 United States House of Representatives election ...

, it was bitterly divided over slavery. The main faction supported the ticket of presidential nominee Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

and vice presidential nominee Andrew Jackson Donelson

Andrew Jackson Donelson (August 25, 1799 – June 26, 1871) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in various positions as a Democrat and was the Know Nothing nominee for US Vice President in 1856.

After the death of his father, Done ...

. Fillmore, a former president, had been a Whig and Donelson was the nephew of Democratic President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, so the ticket was designed to appeal to loyalists from both major parties, winning 23% of the popular vote and carrying one state, Maryland, with eight electoral votes. Fillmore did not win enough votes to block Democrat James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

from the White House. During this time, Nathaniel Banks decided he was not as strongly for the anti-immigrant platform as the party wanted him to be, so he left the Know Nothing Party for the more anti-slavery Republican Party. He contributed to the decline of the Know Nothing Party by taking two-thirds of its members with him.

Many were appalled by the Know Nothings. Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

expressed his own disgust with the political party in a private letter to Joshua Speed

Joshua () or Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' lit. 'Yahweh is salvation') ''Yēšūaʿ''; syr, ܝܫܘܥ ܒܪ ܢܘܢ ''Yəšūʿ bar Nōn''; el, Ἰησοῦς, ar , يُوشَعُ ٱبْنُ نُونٍ '' Yūšaʿ ...

, written 24 August 1855. Lincoln never publicly attacked the Know Nothings, whose votes he needed:

Historian Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

, writing about the turmoil preceding the American Civil War, states that Millard Fillmore was never a Know Nothing nor a nativist. Fillmore was out of the country when the presidential nomination came and had not been consulted about running. Nevins further states:

However, Fillmore had sent a letter for publication in 1855 that explicitly denounced immigrant influence in elections 17and Fillmore stated that the American Party was the "only hope of forming a truly national party, which shall ignore this constant and distracting agitation of slavery."

After the Supreme Court's controversial ''Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

'' ruling in 1857, most of the anti-slavery members of the American Party joined the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

. The pro-slavery wing of the American Party remained strong on the local and state levels in a few southern states, but by the 1860 election they were no longer a serious national political movement. Most of their remaining members supported the Constitutional Union Party in 1860.

Electoral results

Congressional elections

Presidential elections

Legacy

The nativist, anti-Catholic spirit of the Know Nothing movement was revived by later political movements such as the American Protective Association of the 1890s and the SecondKu Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

of the 1920s.William Safire

William Lewis Safire (; Safir; December 17, 1929 – September 27, 2009Safire, William (1986). ''Take My Word for It: More on Language.'' Times Books. . p. 185.) was an American author, columnist, journalist, and presidential speechwriter. He ...

. ''Safire's Political Dictionary'' (2008) pp. 375–76 However, the Know Nothing Party was not a mouthpiece for anti-black racism and anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in the manner in which the 1920s-era Klan was. In the late 19th century, Democrats called the Republicans "Know Nothings" in order to secure the votes of Germans which is exactly what they did in the Bennett Law

The Bennett Law, officially chapter 519 of the 1889 acts of the Wisconsin Legislature, was a controversial state law passed by the Wisconsin Legislature in 1889 dealing with compulsory education. The controversial section of the law was a requi ...

campaign in Wisconsin in 1890. A similar culture war

A culture war is a cultural conflict between social groups and the struggle for dominance of their values, beliefs, and practices. It commonly refers to topics on which there is general societal disagreement and polarization in societal valu ...

took place in Illinois in 1892, where Democrat John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld (December 30, 1847 – March 12, 1902) was an American politician and the 20th Governor of Illinois, serving from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democrat to govern that state since the 1850s. A leading figure of the Pro ...

denounced the Republicans:

Some historians and journalists "have found parallels with the Birther

During Barack Obama's campaign for president in 2008, throughout his presidency and afterwards, there was extensive news coverage of Obama's religious preference, birthplace, and of the individuals questioning his religious belief and citi ...

and Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. Members of the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget def ...

s, seeing the prejudices against Latino immigrants and hostility towards Islam as a similarity". Historians Steve Fraser and Joshue B. Freeman lend their opinion on the Know Nothing and the Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. Members of the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget def ...

s, arguing:

Tea Party populism should also be thought of as a kind of''Know Nothing'' has become a provocative slur, suggesting that the opponent is both nativist and ignorant.identity politics Identity politics is a political approach wherein people of a particular race, nationality, religion, gender, sexual orientation, social background, social class, or other identifying factors develop political agendas that are based upon these i ...of theright Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical .... Almost entirelywhite White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White ..., and disproportionately male and older, Tea Party advocates express a visceral anger at the cultural and, to some extent, political eclipse of an America in which people who looked and thought like them were dominant (an echo, in its own way, of the anguish of the Know-Nothings). A black President, a female speaker of the house, and a gay head of the House Financial Services Committee are evidently almost too much to bear. Though theanti-immigration Opposition to immigration, also known as anti-immigration, has become a significant political ideology in many countries. In the modern sense, immigration refers to the entry of people from one state or territory into another state or territory ...and Tea Party movements so far have remained largely distinct (even with growing ties), they share an emotional grammar: the fear of displacement.

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Alabama for four terms. A member of the Democratic Party, he is best remembered for his staunch segregationist a ...

's 1968 presidential campaign was said by ''Time'' to be under the "neo-Know Nothing banner". Fareed Zakaria

Fareed Rafiq Zakaria (; born 20 January 1964) is an Indian-American journalist, political commentator, and author. He is the host of CNN's ''Fareed Zakaria GPS'' and writes a weekly paid column for ''The Washington Post.'' He has been a columnist ...

wrote that politicians who "encourage Americans to fear foreigners" were becoming "modern incarnations of the Know-Nothings". In 2006, an editorial in ''The Weekly Standard

''The Weekly Standard'' was an American neoconservative political magazine of news, analysis and commentary, published 48 times per year. Originally edited by founders Bill Kristol and Fred Barnes, the ''Standard'' had been described as a "re ...

'' by neoconservative William Kristol

William Kristol (; born December 23, 1952) is an American neoconservative writer. A frequent commentator on several networks including CNN, he was the founder and editor-at-large of the political magazine ''The Weekly Standard''. Kristol is now ...

accused populist Republicans of "turning the GOP into an anti-immigration, Know-Nothing party".Craig Shirley. "How the GOP Lost Its Way", ''The Washington Post'', 22 April 2006, p. A21. The lead editorial of the 20 May 2007 issue of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' on a proposed immigration bill referred to "this generation's Know-Nothings". An editorial written by Timothy Egan in ''The New York Times'' on 27 August 2010 and titled "Building a Nation of Know-Nothings" discussed the birther movement, which falsely claimed that Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

was not a natural-born United States citizen, which is a requirement for the office of president of the United States.

In the 2016 United States presidential election

The 2016 United States presidential election was the 58th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016. The Republican ticket of businessman Donald Trump and Indiana governor Mike Pence defeated the Democratic ticke ...

, a number of commentators and politicians compared candidate Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

to the Know Nothings due to his anti-immigration policies.

In popular culture

The American Party was represented in the 2002 film ''Gangs of New York

''Gangs of New York'' is a 2002 American epic historical drama film directed by Martin Scorsese and written by Jay Cocks, Steven Zaillian and Kenneth Lonergan, based on Herbert Asbury's 1927 book '' The Gangs of New York''. The film stars Le ...

'', led by William "Bill the Butcher" Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis

Sir Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis (born 29 April 1957) is an English retired actor. Often described as one of the preeminent actors of his generation, he received numerous accolades throughout his career which spanned over four decades, incl ...

), the fictionalized version of real-life Know Nothing leader William Poole

William Poole (July 24, 1821 – March 8, 1855), also known as Bill the Butcher, was the leader of the Washington Street Gang, which later became known as the Bowery Boys gang. He was a local leader of the Know Nothing political movement ...

. The Know Nothings also play a prominent role in the historical fiction novel ''Shaman'' by novelist Noah Gordon.

Notable Know Nothings

*Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

The speaker of the United States House of Representatives, commonly known as the speaker of the House, is the presiding officer of the United States House of Representatives. The office was established in 1789 by Article I, Section 2 of the ...

from Massachusetts and Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

general

* Levi Boone, mayor of Chicago

* John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth ...

, actor at Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in August 1863. The theater is infamous for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater bo ...

who assassinated

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

* John Edward Bouligny, congressman from Louisiana; refused to resign when Louisiana seceded from the Union

* Henry Winter Davis, congressman from Maryland

* Andrew Jackson Donelson

Andrew Jackson Donelson (August 25, 1799 – June 26, 1871) was an American diplomat and politician. He served in various positions as a Democrat and was the Know Nothing nominee for US Vice President in 1856.

After the death of his father, Done ...

, Washington D.C. newspaper editor, diplomat to Texas and Prussia, and Andrew Jackson's nephew

* Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

, 13th president of the United States

* Thomas Holliday Hicks

Thomas Holliday Hicks (September 2, 1798February 14, 1865) was a politician in the divided border-state of Maryland during the American Civil War. As governor, opposing the Democrats, his views accurately reflected the conflicting local loyalt ...

, governor of Maryland

* William W. Hoppin, governor of Rhode Island

* Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (, ; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played an important role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two i ...

, senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

from Texas

* J. Neely Johnson

John Neely Johnson (August 2, 1825 – August 31, 1872) was an American lawyer and politician. He was elected as the fourth governor of California from 1856 to 1858, and later appointed justice to the Nevada Supreme Court from 1867 to 1871. As a ...

, governor of California

* Anthony Kennedy

Anthony McLeod Kennedy (born July 23, 1936) is an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1988 until his retirement in 2018. He was nominated to the court in 1987 by Presid ...

, senator from Maryland

* Lewis Charles Levin

Lewis Charles Levin (November 10, 1808 – March 14, 1860) was an American politician, newspaper editor and anti-Catholic social activist. He was one of the founders of the American Party in 1842 and served as a member of the U. S. House of Rep ...

, politician and social activist

* Samuel Morse

Samuel Finley Breese Morse (April 27, 1791 – April 2, 1872) was an American inventor and painter. After having established his reputation as a portrait painter, in his middle age Morse contributed to the invention of a single-wire telegraph ...

, politician, painter and inventor of morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one ...

and the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

* William Poole

William Poole (July 24, 1821 – March 8, 1855), also known as Bill the Butcher, was the leader of the Washington Street Gang, which later became known as the Bowery Boys gang. He was a local leader of the Know Nothing political movement ...

, politician and a founder and leader of the New York City criminal Nativist gang the Bowery Boys

* Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

, congressman from Pennsylvania

* Stephen Palfrey Webb

Stephen Palfrey Webb (March 20, 1804 – September 29, 1879) was an American politician who served as the third and twelfth mayor of Salem, Massachusetts, and the 5th mayor of San Francisco, California.

Early life, family life, education, an ...

, mayor of San Francisco

* Charles S. Morehead

Charles Slaughter Morehead (July 7, 1802 – December 21, 1868) was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky, and served as the 20th Governor of Kentucky. Though a member of the Whig Party for most of his political service, he joined the Know Not ...

, governor of Kentucky

* Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

, 18th vice president of the United States

See also

*71st Infantry Regiment (New York)

The 71st New York Infantry Regiment is an organization of the New York State Guard. Formerly, the 71st Infantry was a regiment of the New York State Militia and then the Army National Guard from 1850 to 1993. The regiment was not renumbered dur ...

* John J. Crittenden

John Jordan Crittenden (September 10, 1787 July 26, 1863) was an American statesman and politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. He represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate and twice served as Unite ...

* James Greene Hardy

James Greene Hardy (May 3, 1795 – July 16, 1856) was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky who belonged to the American or Know-Nothing Party. Prior to being elected the 15th Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky, he was a prominent surv ...

* Samuel Hinks

Samuel Hinks (May 1, 1815 – November 30, 1887) was Mayor of Baltimore, Maryland, from 1854 to 1856. He was a member of the Know Nothing party. He was succeeded in 1856 by fellow Know Nothing Thomas Swann.

Early life

Samuel Hinks was born in ...

* Know-Nothing Riot of 1856

* Philadelphia Nativist Riots

The Philadelphia nativist riots (also known as the Philadelphia Prayer Riots, the Bible Riots and the Native American Riots) were a series of riots that took place on May 68 and July 67, 1844, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States and the ...

* Thomas Swann

Thomas Swann (February 3, 1809 – July 24, 1883) was an American lawyer and politician who also was President of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as it completed track to Wheeling and gained access to the Ohio River Valley. Initially a Know-N ...

* Third Party System

In the terminology of historians and political scientists, the Third Party System was a period in the history of political parties in the United States from the 1850s until the 1890s, which featured profound developments in issues of American n ...

* Xenophobia in the United States

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Anbinder, Tyler. ''Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the politics of the 1850s'' (1992). online at ACLS History e-Book;, the standard scholarly study * Anbinder, Tyler. "Nativism and prejudice against immigrants," in ''A companion to American immigration'', ed. by Reed Ueda (2006) pp. 177–20online excerpt

* Baker, Jean H. (1977), ''Ambivalent Americans: The Know-Nothing Party in Maryland'', Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. * Baum, Dale. "Know-Nothingism and the Republican Majority in Massachusetts: The Political Realignment of the 1850s." ''Journal of American History'' 64 (1977–78): 959–86

in JSTOR

* Baum, Dale. ''The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848–1876'' (1984) * Bennett, David H. ''The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History'' (1988

online

* Billington, Ray A. ''The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism'' (1938), standard scholarly survey

online

* Bladek, John David. "'Virginia Is Middle Ground': the Know Nothing Party and the Virginia Gubernatorial Election of 1855." ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' 1998 106(1): 35–70

in JSTOR

* Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics." ''Smithsonian Magazine'' (2017), heavily illustrated with editorial cartoons

online

* Cheathem, Mark R. "'I Shall Persevere in the Cause of Truth': Andrew Jackson Donelson and the Election of 1856". ''Tennessee Historical Quarterly'' 2003 62(3): 218–237. Donelson was Andrew Jackson's nephew and K–N nominee for Vice President * Dash, Mark. "New Light on the Dark Lantern: the Initiation Rites and Ceremonies of a Know-Nothing Lodge in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania" ''Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 2003 127(1): 89–100. * Desmond, Humphrey J. ''The Know-Nothing Party'' (1905

online

* Gienapp, William E. "Nativism and the Creation of a Republican Majority in the North before the Civil War," ''Journal of American History'', Vol. 72, No. 3 (Dec., 1985), pp. 529–55

in JSTOR

* Gienapp, William E. ''The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856'' (1978), detailed statistical study, state-by-state * Gillespie, J. David. ''Challengers To Duopoly : Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics.'' Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2012. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 4 Dec. 2014. * Gleeson, David T. ''The Irish in the South, 1815–1877'' Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. * Haebler, Peter. "Nativist Riots in Manchester: An Episode of Know-Nothingism in New Hampshire." ''Historical New Hampshire'' 39 (1985): 121-37. * Holt, Michael F. ''The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party'' (1999) * Holt, Michael F. ''Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln'' (1992) * Holt, Michael F. "The Antimasonic and Know Nothing Parties", in Arthur Schlesinger Jr., ed., ''History of United States Political Parties'' (1973), I, 575–620. * Hurt, Payton. "The Rise and Fall of the 'Know Nothings' in California," ''California Historical Society Quarterly'' 9 (March and June 1930). * Kadir, Djelal. "Agnotology and the Know-Nothing Party: Then and Now." ''Review of International American Studies'' 10.1 (2017): 117–131

online

* Levine, Bruce. "Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-nothing Party" ''Journal of American History'' 2001 88(2): 455–488

in JSTOR

* McGreevey, John T. ''Catholicism and American Freedom: A History'' (W. W. Norton, 2003) * Maizlish, Stephen E. "The Meaning of Nativism and the Crisis of the Union: The Know-Nothing Movement in the Antebellum North." in William Gienapp, ed. ''Essays on American Antebellum Politics, 1840–1860'' (1982) pp. 166–98 * Melton, Tracy Matthew. ''Hanging Henry Gambrill: The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, 1854–1860''. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society (2005). * Mulkern, John R. ''The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People's Movement''. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1990

excerpt

* Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing, 1852–1857'' (1947), overall political survey of era * Overdyke, W. Darrell. ''The Know-Nothing Party in the South'' (1950) * Ramet, Sabrina P., and Christine M. Hassenstab. "The Know Nothing Party: Three Theories about its Rise and Demise." ''Politics and Religion'' 6.3 (2013): 570–595. * Parmet, Robert D. "Connecticut's Know-Nothings: A Profile," ''Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin'' (1966), 31 #3, pp. 84–90 * Rice, Philip Morrison. "The Know-Nothing Party in Virginia, 1854–1856." ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography'' (1947): 61–75

in JSTOR

* Roseboom, Eugene H. "Salmon P. Chase and the Know Nothings." ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 25.3 (1938): 335-350

online

* Scisco, Louis Dow. ''Political Nativism in New York State'' (1901

full text online

pp. 84–202 * Taylor, Steven. "Progressive Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts" ''Historical Journal of Massachusetts'' (2000) 28#

online

* Voss-Hubbard, Mark. ''Beyond Party: Cultures of Antipartisanship in Northern Politics before the Civil War'' (2002) * Wilentz, Sean. ''The Rise of American Democracy.'' (2005);

Primary sources

* Anspach, Frederick Rinehart''The Sons of the Sires: A History of the Rise, Progress, and Destiny of the American Party''

Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1855. Work by K–N activist. * Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics." ''Smithsonian Magazine'' (2017), heavily illustrated with editorial cartoons

online

* Busey, Samuel Clagett (1856)

''Immigration: Its Evils and Consequences''

* Carroll, Anna Ella (1856)

''The Great American Battle: Or, The Contest Between Christianity and Political Romanism''

* Fillmore, Millard; Frank H. Severance (ed.)(1907)

''Millard Fillmore Papers''

* One of Them

''The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855''

New York: J.C. Derby, 1855. ** Bond, Thomas E

"The 'Know Nothings

from ''The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855''. New York: J. C. Derby, 1855; pp. 54–63.

External links

Nativism in the 1856 Presidential Election

* *

* {{authority control American nationalist parties American nationalists Anti-Catholicism in the United States Anti-Catholic organizations Anti-German sentiment in the United States Anti-immigration politics in the United States Anti-Irish sentiment Defunct American political movements Defunct far-right political parties in the United States 1850s in the United States Political parties in the United States Right-wing populism in the United States Conservatism in the United States