King assassination riots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The King assassination riots, also known as the Holy Week Uprising, were a wave of

On April 4, President Lyndon B. Johnson denounced King's murder. He also began to communicate with a host of mayors and governors preparing for a reaction from black America. He cautioned against unnecessary force, but felt like local governments would ignore his advice, saying to aides, "I'm not getting through. They're all holing up like generals in a dugout getting ready to watch a war."

On April 5, at 11:00 AM, Johnson met with an array of leaders in the Cabinet Room. These included Vice President

On April 4, President Lyndon B. Johnson denounced King's murder. He also began to communicate with a host of mayors and governors preparing for a reaction from black America. He cautioned against unnecessary force, but felt like local governments would ignore his advice, saying to aides, "I'm not getting through. They're all holing up like generals in a dugout getting ready to watch a war."

On April 5, at 11:00 AM, Johnson met with an array of leaders in the Cabinet Room. These included Vice President

Letter

to Maj. Gen. Thomas G. Wells authorizing him to command national guard and military forces for riot control in Memphis. {{Martin Luther King Jr. 1968 in the United States 1968 riots Post–civil rights era in African-American history African-American riots in the United States Martin Luther King Jr. Riots Riots and civil disorder in the United States April 1968 events in the United States May 1968 events in the United States Articles containing video clips Ghetto riots (1964–1969)

civil disturbance

Civil disorder, also known as civil disturbance, civil unrest, or social unrest is a situation arising from a mass act of civil disobedience (such as a demonstration, riot, strike, or unlawful assembly) in which law enforcement has difficulty ...

which swept the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at ...

on April 4, 1968. Many believe them to be the greatest wave of social unrest the United States had experienced since the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

. Some of the biggest riots took place in Washington, D.C., Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, and Kansas City

The Kansas City metropolitan area is a bi-state metropolitan area anchored by Kansas City, Missouri. Its 14 counties straddle the border between the U.S. states of Missouri (9 counties) and Kansas (5 counties). With and a population of more th ...

.

Overview

Causes

The immediate cause of the rioting was theassassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at ...

King was not only a leader in the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

, but also an advocate for nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. He pursued direct engagement with the political system (as opposed to the separatist ideas of black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves aro ...

). His death led to anger and disillusionment, and feelings that, thereafter, only violent resistance to white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

could be effective.

Riots

The protesters were mostly black; not all were poor. Middle-class black people also demonstrated against systemic inequality. Although the media called these events "race riots", there were few confirmed acts of violence between black and white people. White businesses tended to be targeted; however, white public and community buildings such as schools and churches were largely spared. Compared to the previous summer of rioting, the number of fatalities was lower, largely attributed to new procedures instituted by the federal government, and orders not to fire on looters.Events by city

InNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, mayor John Lindsay

John Vliet Lindsay (; November 24, 1921 – December 19, 2000) was an American politician and lawyer. During his political career, Lindsay was a U.S. congressman, mayor of New York City, and candidate for U.S. president. He was also a regular ...

traveled directly into Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

, telling black residents that he regretted King's death and was working against poverty. He is credited for averting major riots in New York with this direct response although minor disturbances still erupted in the city. In Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, Senator Robert F. Kennedy's speech on the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. is credited with preventing a riot there. In Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, rioting may have been averted by a James Brown

James Joseph Brown (May 3, 1933 – December 25, 2006) was an American singer, dancer, musician, record producer and bandleader. The central progenitor of funk music and a major figure of 20th century music, he is often referred to by the hono ...

concert taking place on the night of April 5, with Brown, Mayor Kevin White, and City Councilor Tom Atkins speaking to the Garden crowd about peace and unity before the show.

In Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, the Los Angeles Police Department

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), officially known as the City of Los Angeles Police Department, is the municipal police department of Los Angeles, California. With 9,974 police officers and 3,000 civilian staff, it is the third-lar ...

and community activists averted a repeat of the 1965 riots

Events January–February

* January 14 – The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is Second inauguration of Lyndo ...

that devastated portions of the city. Several memorials were held in tribute to King throughout the Los Angeles area on the days leading into his funeral service.

Washington, D.C.

The Washington, D.C., riots of April 4–8, 1968, resulted in Washington, along withChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

and Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, receiving the heaviest impact of the 110 cities to see unrest following the King assassination.

The ready availability of jobs in the growing federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-gover ...

attracted many to Washington since the early 20th century, and middle class African-American neighborhood

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American ...

s prospered. Despite the end of legally mandated racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crime against humanity under the Statute of the Intern ...

, the historic neighborhoods of Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

* Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

* Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

* Shaw, Swindon, a suburb of Swindon

...

, the H Street Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

corridor, and Columbia Heights, centered at the intersection of 14th and U Streets Northwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each s ...

, remained the centers of African-American commercial life in the city.

As word of King's murder by James Earl Ray

James Earl Ray (March 10, 1928 – April 23, 1998) was an American fugitive convicted for assassinating Martin Luther King Jr. at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. After this Ray was on the run and was cap ...

in Memphis spread on the evening of Thursday, April 4, crowds began to gather at 14th and U. Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

led members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

(SNCC) to stores in the neighborhood demanding that they close out of respect. Although polite at first, the crowd fell out of control and began breaking windows. By 11pm, widespread looting had begun.

Mayor-Commissioner Walter Washington ordered the damage cleaned up immediately the next morning. However, anger was still evident on Friday morning when Carmichael addressed a rally at Howard, warning of violence. After the close of the rally, crowds walking down 7th Street NW and in the H Street NE corridor came into violent confrontations with police. By midday, numerous buildings were on fire, and firefighters were prevented from responding by crowds attacking with bottles and rocks.

Crowds of as many as 20,000 overwhelmed the District's 3,100-member police force, and 11,850 federal troops and 1,750 D.C. National Guard

The District of Columbia National Guard is the branch of the United States National Guard based in the District of Columbia. It comprises both the D.C. Army National Guard and the D.C. Air National Guard components.

The president of the Unit ...

smen under orders of President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Lyndon B. Johnson arrived on the streets of D.C. to assist them. Marines mounted machine guns on the steps of the Capitol and Army soldiers from the 3rd Infantry guarded the White House. At one point, on April 5, rioting reached within two blocks of the White House before rioters retreated. The occupation of Washington was the largest of any American city since the Civil War. Mayor Washington imposed a curfew and banned the sale of alcohol and guns in the city. By the time the city was considered pacified on Sunday, April 8, some 1,200 buildings had been burned, including over 900 stores. Damages reached $27 million.

The riots utterly devastated Washington's inner city economy. With the destruction or closing of businesses, thousands of jobs were lost, and insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

rates soared. Made uneasy by the violence, city residents of all races accelerated their departure for suburb

A suburb (more broadly suburban area) is an area within a metropolitan area, which may include commercial and mixed-use, that is primarily a residential area. A suburb can exist either as part of a larger city/urban area or as a separ ...

an areas, depressing property values. Crime

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in C ...

in the burned out neighborhoods rose sharply, further discouraging investment.

On some blocks, only rubble remained for decades. Columbia Heights and the U Street corridor did not begin to recover economically until the opening of the U Street and Columbia Heights Metro stations in 1991 and 1999, respectively, while the H Street NE corridor remained depressed for several years longer.

Mayor-Commissioner Washington, who was the last presidentially appointed mayor of Washington, went on to become the city's first elected mayor.

Chicago

On April 5, one day after King was assassinated, violence sparked on the West side of Chicago. It eventually expanded to consume a 28-block stretch of West Madison Street, with additional damage occurring on Roosevelt Road. TheNorth Lawndale

North Lawndale is one of the 77 community areas of the city of Chicago, Illinois, located on its West Side. The area contains the K-Town Historic District, the Foundation for Homan Square, the Homan Square interrogation facility, and the great ...

and East Garfield Park neighborhoods on the West Side and the Woodlawn neighborhood on the South Side experienced the majority of the destruction and chaos. The rioters broke windows, looted stores, and set buildings (both abandoned and occupied) on fire. Firefighters quickly flooded the neighborhood, and Chicago's off-duty firefighters were told to report for duty. There were 36 major fires reported between 4:00 pm and 10:00 pm alone. The next day, Mayor Richard J. Daley imposed a curfew on anyone under the age of 21, closed the streets to automobile traffic, and halted the sale of guns or ammunition.

Approximately 10,500 police were sent in, and by April 6, more than 6,700 Illinois National Guard

The Illinois National Guard comprises both Army National Guard and Air National Guard components of Illinois. As of 2013, the Illinois National Guard has approximately 13,200 members. The National Guard is the only United States military force em ...

troops had arrived in Chicago with 5,000 regular Army soldiers from the 1st Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions being ordered into the city by President Johnson. The General in charge declared that no one was allowed to have gatherings in the riot areas, and he authorized the use of tear gas. Mayor Richard J. Daley gave police the authority "to shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand ... and ... to shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting any stores in our city."

By the time order was restored on April 7, 11 people had died, 500 had been injured, and 2,150 had been arrested. Over 200 buildings were damaged in the disturbance with damage costs running up to $10 million.

The south side ghetto had escaped the major chaos mainly because the two large street gangs, the Blackstone Rangers

The Almighty Black P. Stone Nation often abbreviated as (BPS, BPSN, Black Peace Stones, Black P. Stones, Stones, or Moes) is an American street gang founded in Chicago. The gang was originally formed in the late 1950s as the Blackstone Rangers. ...

and the East Side Disciples, cooperated to control their neighborhoods. Many gang members did not participate in the rioting, due in part to King's direct involvement with these groups in 1966.

Baltimore

The Baltimore riot of 1968 began two days after the murder. On Saturday, April 6, the Governor of Maryland,Spiro T. Agnew

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the 39th vice president of the United States, serving from 1969 until his resignation in 1973. He is the second vice president to resign the position, the other being John ...

, called out thousands of National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

troops and 500 Maryland State Police to quell the disturbance. When it was determined that the state forces could not control the riot, Agnew requested Federal troops from President Lyndon B. Johnson. The riot was precipitated by King's assassination, but was also evidence of larger frustrations among the city's African-American population.

By Sunday evening, 5,000 paratrooper

A paratrooper is a military parachutist—someone trained to parachute into a military operation, and usually functioning as part of an airborne force. Military parachutists (troops) and parachutes were first used on a large scale during Worl ...

s, combat engineer

A combat engineer (also called pioneer or sapper) is a type of soldier who performs military engineering tasks in support of land forces combat operations. Combat engineers perform a variety of military engineering, tunnel and mine warfare tas ...

s, and artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during si ...

men from the XVIII Airborne Corps

The XVIII Airborne Corps is a corps of the United States Army that has been in existence since 1942 and saw extensive service during World War II. The corps is designed for rapid deployment anywhere in the world and is referred to as "America ...

in Fort Bragg, North Carolina

Fort Bragg is a military installation of the United States Army in North Carolina, and is one of the largest military installations in the world by population, with around 54,000 military personnel. The military reservation is located within C ...

, specially trained in tactics, including sniper

A sniper is a military/paramilitary marksman who engages targets from positions of concealment or at distances exceeding the target's detection capabilities. Snipers generally have specialized training and are equipped with high-precision r ...

school, were on the streets of Baltimore with fixed bayonets, and equipped with chemical (CS) disperser backpacks. Two days later, they were joined by a Light Infantry Brigade from Fort Benning, Georgia

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

. With all the police and troops on the streets, the situation began to calm down. The Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice ...

reported that H. Rap Brown was in Baltimore driving a Ford Mustang

The Ford Mustang is a series of American automobiles manufactured by Ford. In continuous production since 1964, the Mustang is currently the longest-produced Ford car nameplate. Currently in its sixth generation, it is the fifth-best selli ...

with Broward County, Florida tags, and was assembling large groups of angry protesters and agitating them to escalate the rioting. In several instances, these disturbances were rapidly quelled through the use of bayonets and chemical dispersers by the XVIII Airborne units. That unit arrested more than 3,000 detainees, who were turned over to the Baltimore Police. A general curfew was set at 6 p.m. in the city limits and martial law was enforced. As rioting continued, African American plainclothes police officers and community leaders were sent to the worst areas to prevent further violence. By the end of the unrest, 6 people had died, 700 were injured, and 5,800 had been arrested; property damage was estimated at over $12 million.

One of the major outcomes of the riot was the attention Governor Agnew received when he criticized local black leaders for not doing enough to help stop the disturbance. While this angered black people and white liberals, it caught the attention of Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, who was looking for someone on his ticket who could counter George Wallace's American Independent Party

The American Independent Party (AIP) is a far-right political party in the United States that was established in 1967. The AIP is best known for its nomination of former Democratic Governor George Wallace of Alabama, who carried five states in t ...

campaign. Agnew became Nixon's vice presidential running mate in 1968

The year was highlighted by protests and other unrests that occurred worldwide.

Events January–February

* January 5 – " Prague Spring": Alexander Dubček is chosen as leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

* J ...

.

Kansas City

The rioting in Kansas City did not erupt on April 4, like other cities of the United States affected directly by the assassination of King, but rather on April 9 after local events within the city. The riot was sparked when Kansas City Police Department deployed tear gas against student protesters when they staged their performances outside City Hall. The deployment of tear gas dispersed the protesters from the area, but other citizens of the city began to riot as a result of the police action on the student protesters. The resulting effects of the riot resulted in the arrest of over 100 adults, and left six dead and at least 20 admitted to hospitals.Detroit

Although not as large as other cities, violent disturbances did erupt in Detroit. Michigan Governor George W. Romney ordered the National Guard into Detroit. One person was killed, and gangs tossed objects at cars and smashed storefront windows along 12th Street on the west side.New York City

Riots erupted in New York City the night King was murdered. Sporadic violence and looting occurred inHarlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

, the largest African-American neighborhood in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Tensions simmered down after Mayor John Lindsay traveled into the heart of the area and stated that he regretted King's wrongful death. However, numerous businesses were still looted and set afire in Harlem and Brooklyn following the statement.

Pittsburgh

Disturbances erupted in Pittsburgh on April 5 and continued through April 11. The riot peaked on April 7 in which one person was killed and 3,600 National Guardsmen were deployed into the city. Over 100 businesses were either looted or burned in the Hill District, Homewood, and North Side neighborhoods with various structures being set afire by arsonists. The riot left many of the city's black commercial districts in shambles and the areas most impacted by the unrest were slow to recover in the following decades.Cincinnati

The Cincinnati riots were in response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968. Tension in the Avondale neighborhood had already been high due to a lack of job opportunities for African-American men, and the assassination escalated that tension. On April 8, around 1,500 black people attended a memorial held at a local recreation center. An officer of the Congress of Racial Equality blamed white Americans for King's death and urged the crowd to retaliate. The crowd was orderly when it left the memorial and spilled out into the street. Nearby James Smith, a black man, attempted to protect a jewelry store from a robbery with his own shotgun. During the struggle with the robbers, also black, Smith accidentally shot and killed his wife. Rioting started after a false rumor was spread in the crowd that Smith's wife was actually killed by a white police officer. Rioters smashed store windows and looted merchandise. More than 70 fires had been set, several of them major. During the rioting eight young African Americans dragged a white student, Noel Wright, and his wife from their car in Mount Auburn. Wright was stabbed to death and his wife was beaten. The next night, the city was put under curfew, and nearly 1,500 National Guardsmen were brought in to subdue the violence. Several days after the riot started, two people were dead, hundreds were arrested, and the city had suffered $3 million in property damage.Trenton, New Jersey

The Trenton Riots of 1968 were a major civil disturbance that took place during the week following theassassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., an African-American clergyman and civil rights leader, was fatally shot at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968, at 6:01 p.m. CST. He was rushed to St. Joseph's Hospital, where he died at ...

in Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mo ...

, on April 4. More than 200 Trenton businesses, mostly in Downtown, were ransacked and burned. More than 300 people, most of them young black men, were arrested on charges ranging from assault and arson to looting and violating the mayor's emergency curfew. In addition to 16 injured policemen, 15 firefighters were treated at city hospitals for smoke inhalation, burns, sprains and cuts suffered while fighting raging blazes or for injuries inflicted by rioters. Denizens of Trenton's urban core often pulled false alarms and would then throw bricks at firefighters responding to the alarm boxes. This experience, along with similar experiences in other major cities, effectively ended the use of open-cab fire engines. As an interim measure, the Trenton Fire Department fabricated temporary cab enclosures from steel deck plating until new equipment could be obtained. The losses incurred by downtown businesses were initially estimated by the city to be $7 million, but the total of insurance claims and settlements came to $2.5 million.

Trenton's Battle Monument

The Battle Monument, located in Battle Monument Square on North Calvert Street between East Fayette and East Lexington Streets in Baltimore, Maryland, commemorates the Battle of Baltimore with the British fleet of the Royal Navy's bombardment ...

neighborhood was hardest hit. Since the 1950s, North Trenton had witnessed a steady exodus of middle-class residents, and the riots spelled the end for North Trenton. By the 1970s, the region had become one of the most blighted and crime-ridden in the city, although gentrification

Gentrification is the process of changing the character of a neighborhood through the influx of more affluent residents and businesses. It is a common and controversial topic in urban politics and planning. Gentrification often increases the ec ...

in the area eventually followed.

Wilmington, Delaware

The two-day riot that occurred after King's assassination was small compared with riots in other cities, but its aftermath – a -month occupation by theNational Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

– highlighted the depth of Wilmington's racial problem. During the riot, which occurred on April 9–10, 1968, the mayor asked for a small number of National Guardsmen to help restore order. Democratic Governor Charles L. Terry (a southern-style Democrat) sent in the entire state National Guard and refused to remove them after the rioting was brought under control. Republican Russell W. Peterson defeated Governor Terry, and upon his inauguration in January 1969, Governor Peterson ended the National Guard's occupation in Wilmington.

The Occupation of Wilmington caused scars on the city and its people that have lasted to this day. Some suburbanites grew fearful of traveling into Wilmington in broad daylight, even to attend church on Sunday morning. Over the next few years businesses relocated, taking their employees, customers and tax payments with them.

Louisville

Riots occurred inLouisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, in May 1968. As in many other cities around the country, there were unrest and riots partially in response to the assassination. On May 27, 1968, a group of 400 people, mostly Black people, gathered at Twenty-Eight and Greenwood Streets, in the Parkland neighborhood. The intersection, and Parkland in general, had recently become an important location for Louisville's black community, as the local NAACP branch had moved its office there.

The crowd was protesting the possible reinstatement of a white officer who had been suspended for beating an African-American man some weeks earlier. Several community leaders arrived and told the crowd that no decision had been reached, and alluded to disturbances in the future if the officer was reinstated. By 8:30, the crowd began to disperse.

However, rumors (which turned out to be untrue) were spread that Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee speaker Stokely Carmichael

Kwame Ture (; born Stokely Standiford Churchill Carmichael; June 29, 1941November 15, 1998) was a prominent organizer in the civil rights movement in the United States and the global pan-African movement. Born in Trinidad, he grew up in the Unite ...

's plane to Louisville was being intentionally delayed by white people. After bottles were thrown by the crowd, the crowd became unruly and police were called. However the small and unprepared police response simply upset the crowd more, which continued to grow. The police, including a captain who was hit in the face by a bottle, retreated, leaving behind a patrol car, which was turned over and burned.

By midnight, rioters had looted stores as far east as Fourth Street, overturned cars and started fires.

Within an hour, Mayor Kenneth A. Schmied requested 700 Kentucky National Guard troops and established a citywide curfew. Violence and vandalism continued to rage the next day, but had subdued somewhat by May 29. Business owners began to return, although troops remained until June 4. Police made 472 arrests related to the riots. Two African-American teenagers had died, and $200,000 in damage had been done.

The disturbances had a longer-lasting effect. Most white business owners quickly pulled out or were forced out of Parkland and surrounding areas. Most white residents also left the West End, which had been almost entirely white north of Broadway, from subdivision until the 1960s. The riot would have effects that shaped the image which white people would hold of Louisville's West End, that it was predominantly black and crime-ridden.

Local issues

The assassinations triggered active unrest in communities that were already discontented. For example, theMemphis sanitation strike

The Memphis sanitation strike began on February 12, 1968, in response to the deaths of sanitation workers Echol Cole and Robert Walker.Estes, S. (2000). `I AM A MAN A MAN?’: Race, Masculinity, and the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike. ''Labor ...

, which was already underway, took on a new level of urgency. It was to these striking workers that King delivered his final speech, and in Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

that he was killed. Negotiations on April 16 brought an end to the strike and a promise of better wages.

In Oakland, increasing friction between Black Panthers and the police led to the death of Bobby Hutton

Robert James Hutton (April 21, 1950 – April 6, 1968), also known as "Lil' Bobby", was the treasurer and first recruit to join the Black Panther Party.

.

Official responses

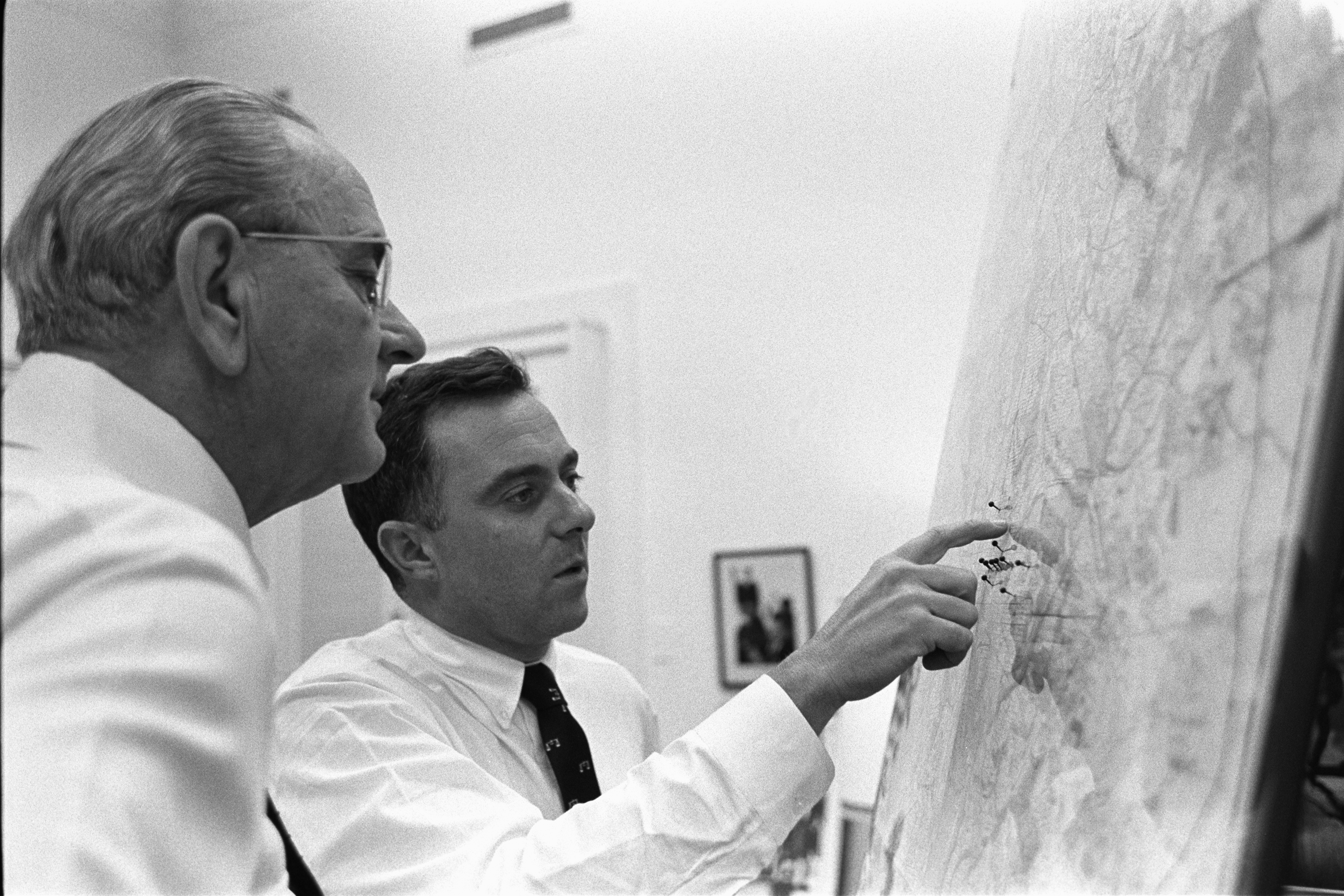

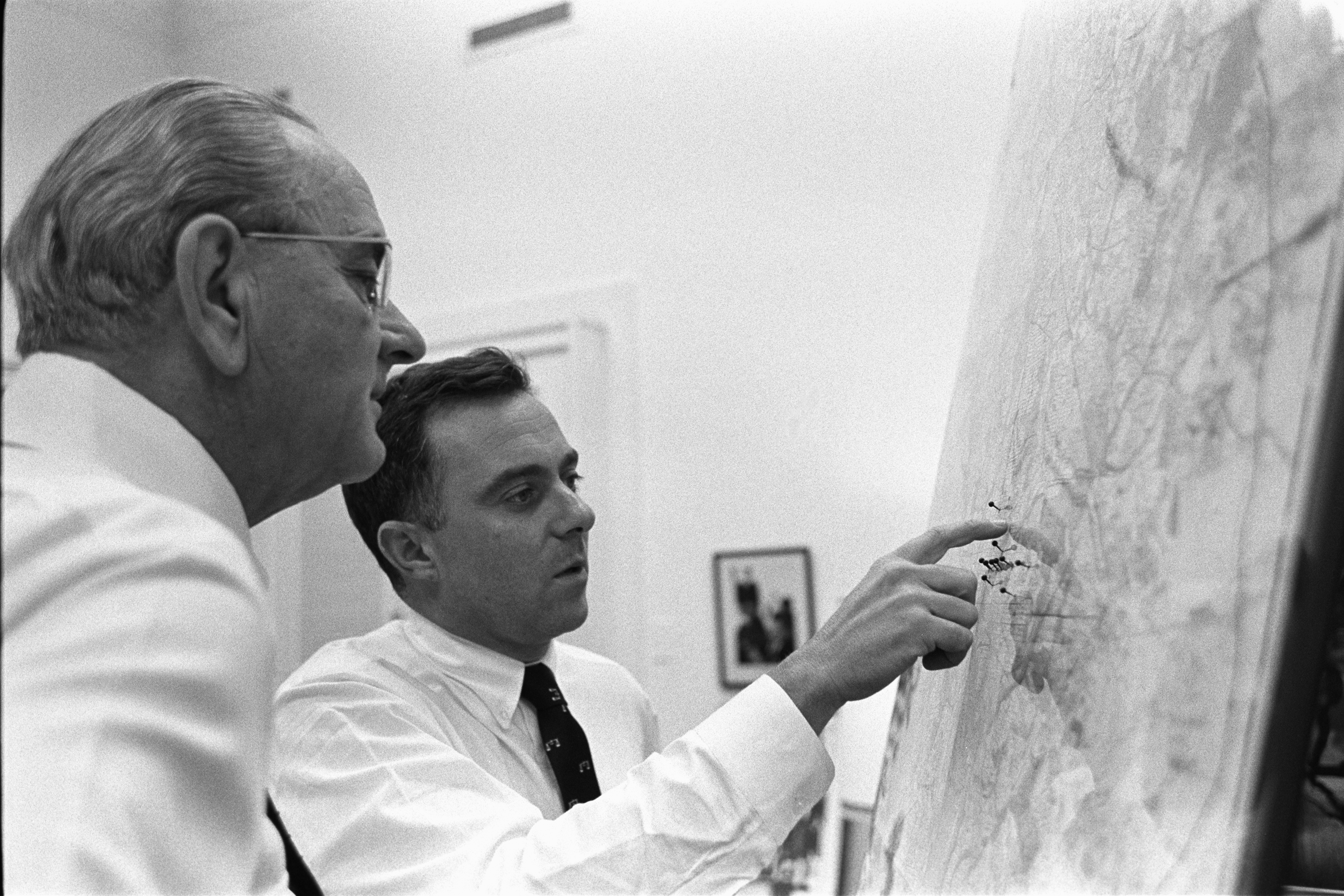

President Johnson

On April 4, President Lyndon B. Johnson denounced King's murder. He also began to communicate with a host of mayors and governors preparing for a reaction from black America. He cautioned against unnecessary force, but felt like local governments would ignore his advice, saying to aides, "I'm not getting through. They're all holing up like generals in a dugout getting ready to watch a war."

On April 5, at 11:00 AM, Johnson met with an array of leaders in the Cabinet Room. These included Vice President

On April 4, President Lyndon B. Johnson denounced King's murder. He also began to communicate with a host of mayors and governors preparing for a reaction from black America. He cautioned against unnecessary force, but felt like local governments would ignore his advice, saying to aides, "I'm not getting through. They're all holing up like generals in a dugout getting ready to watch a war."

On April 5, at 11:00 AM, Johnson met with an array of leaders in the Cabinet Room. These included Vice President Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Mi ...

, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall

Thurgood Marshall (July 2, 1908 – January 24, 1993) was an American civil rights lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1967 until 1991. He was the Supreme Court's first African-A ...

, and federal judge Leon Higginbotham; government officials such as secretary Robert Weaver and D.C. Mayor Walter Washington; legislators Mike Mansfield

Michael Joseph Mansfield (March 16, 1903 – October 5, 2001) was an American politician and diplomat. A Democrat, he served as a U.S. representative (1943–1953) and a U.S. senator (1953–1977) from Montana. He was the longest-serving Sen ...

, Everett Dirksen

Everett McKinley Dirksen (January 4, 1896 – September 7, 1969) was an American politician. A Republican, he represented Illinois in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. As Senate Minority Leader from 1959 u ...

, William McCulloch; and civil rights leaders Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban ...

, Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the ...

, Clarence Mitchell, Dorothy Height

Dorothy Irene Height (March 24, 1912 – April 20, 2010) was an African American civil rights and women's rights activist. She focused on the issues of African American women, including unemployment, illiteracy, and voter awareness. Height is cr ...

, and Walter Fauntroy

Walter Edward Fauntroy (born February 6, 1933) is an American pastor, civil rights activist, and politician who was a delegate to the United States House of Representatives and a candidate for the 1972 and 1976 Democratic presidential nomination ...

. Notably absent were representatives of more radical groups such as SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segreg ...

and CORE

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the centra ...

. At the meeting, Mayor Washington asked President Johnson to deploy troops to the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

. Richard Hatcher

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

, the newly elected black mayor of Gary, Indiana

Gary is a city in Lake County, Indiana, United States. The city has been historically dominated by major industrial activity and is home to U.S. Steel's Gary Works, the largest steel mill complex in North America. Gary is located along the sou ...

, spoke to the group about white racism and his fears of racially motivated violence in the future. Many of these leaders told Johnson that socially progressive legislation would be the best response to the crisis. The meeting concluded with prayers at the Washington National Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington, commonly known as Washington National Cathedral, is an American cathedral of the Episcopal Church. The cathedral is located in Washington, D.C., the ca ...

.

According to press secretary George Christian, Johnson was not surprised by the riots that followed: "What did you expect? I don't know why we're so surprised. When you put your foot on a man's neck and hold him down for three hundred years, and then you let him up, what's he going to do? He's going to knock your block off."

Military deployment

After the Watts riots in 1965 and the Detroit riot of 1967, the military began preparing heavily for black insurrection. The Pentagon's Army Operations Center thus quickly began its response to the assassination on the night of April 4, directing air force transport planes to prepare for an occupation of Washington, D.C. The Army also dispatched undercover agents to gather information. On April 5, Johnson ordered mobilization of theArmy

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

, particularly for D.C.

Legislative response

Some responded to the riots with suggestions for improving the conditions that engendered them. Many White House aides took the opportunity to push their preferred programs for urban improvement. At the same time, some members of Congress criticized Johnson. Senator Richard Russell felt Johnson was not going far enough to suppress the violence. SenatorRobert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A ...

suggested that Washington, D.C. ought to be occupied indefinitely by the army.

Johnson chose to focus his political capital

Political capital is the term used for an individual's ability to influence political decisions. This capital is built from what the opposition thinks of the politician, so radical politicians will lose capital. Political capital can be understoo ...

on a fair housing bill proposed by Senator Sam Ervin

Samuel James Ervin Jr. (September 27, 1896April 23, 1985) was an American politician. A Democrat, he served as a U.S. Senator from North Carolina from 1954 to 1974. A native of Morganton, he liked to call himself a "country lawyer", and often ...

. He urged Congress to pass the bill, starting with an April 5 letter addressed to the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, John William McCormack. These events led to the rapid passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Title VIII of which is known as the "Fair Housing Act".

President's communication with local governments

Audio records reveal a tense and variable relationship between Johnson and local officials. In conversations with Chicago mayorRichard J. Daley

Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the Mayor of Chicago from 1955 and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee from 1953 until his death. He has been cal ...

, Johnson describes the complications with ordering federal troops before local governments have exhausted all options. Later, Johnson would describe the domestic unrest as another front in the global war, criticizing Daley for not requesting troops sooner. From the transcript:

In the same call, Johnson told Daley he wanted to use a strategy of pre-emption: "I'd rather move them and not need them than need them and not have them."

Impact

Dozens of people were killed, and thousands of people injured, in the rioting over April 4 to 5.Physical

Some areas were heavily damaged by the riots, and recovered slowly. In Washington DC, poor urban planning decisions on the part of the federal and local government were an obstacle to recovery.Political

Dr. King had campaigned for a federal fair housing law throughout 1966, but had not achieved it. SenatorWalter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928 – April 19, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 42nd vice president of the United States from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. A U.S. senator from Minnesota ...

advocated for the bill in Congress, but noted that over successive years, a fair housing bill was the most filibustered legislation in US history. It was opposed by most Northern and Southern senators, as well as the National Association of Real Estate Boards

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) is an American trade association for those who work in the real estate industry. It has over 1.4 million members, making it one of the biggest trade associations in the USA including NAR's institutes, so ...

. Mondale commented that:

The riots quickly revived the bill. On April 5, Johnson wrote a letter to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

urging passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which included the Fair Housing Act. The Rules Committee, "jolted by the repeated civil disturbances virtually outside its door," finally ended its hearings on April 8. With newly urgent attention from White House legislative director Joseph Califano

Joseph Anthony Califano Jr. (born May 15, 1931) is an American attorney, professor, and public servant. He is known for the roles he played in shaping welfare policies in the cabinets of Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Jimmy Carter and for se ...

and Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

John McCormack, the bill—which was previously stalled that year—passed the House by a wide margin on April 10.

Social

For some liberals and civil rights advocates, the riots were a turning point. They increased an already-strong trend towardracial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and white flight

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They refer ...

in America's cities, strengthening racial barriers that looked as though they might weaken. The riots were political fodder for the Republican party, which used fears of black urban crime to garner support for "law and order", especially in the 1968 presidential campaign. The assassination and riots radicalized many, helping to fuel the Black Power movement.

See also

* Red Summer (1919) * Long Hot Summer (1967) * George Floyd Protests (2020) * Post-civil rights era African-American history *List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Listed are major episodes of civil unrest in the United States. This list does not include the numerous incidents of destruction and violence associated with various sporting events.

18th century

*1783 – Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, June 20 ...

*'' Black Rage''

References

External links

Letter

to Maj. Gen. Thomas G. Wells authorizing him to command national guard and military forces for riot control in Memphis. {{Martin Luther King Jr. 1968 in the United States 1968 riots Post–civil rights era in African-American history African-American riots in the United States Martin Luther King Jr. Riots Riots and civil disorder in the United States April 1968 events in the United States May 1968 events in the United States Articles containing video clips Ghetto riots (1964–1969)