Karl August Freiherr von Hardenberg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Karl August Fürst von Hardenberg (31 May 1750, in Essenrode-

Hardenberg was the eldest son of Christian Ludwig von Hardenberg (1700-1781), a Hanoverian colonel, later to become field marshal and commander-in-chief of the

Hardenberg was the eldest son of Christian Ludwig von Hardenberg (1700-1781), a Hanoverian colonel, later to become field marshal and commander-in-chief of the

In 1814, King Frederick William III vested Hardenberg with the locality of Quilitz, together with the princely title, as a gratification for his merits as Prussian state chancellor. When he received the manor, he renamed the place right away into ''

In 1814, King Frederick William III vested Hardenberg with the locality of Quilitz, together with the princely title, as a gratification for his merits as Prussian state chancellor. When he received the manor, he renamed the place right away into ''

Lehre

Lehre is a municipality in the district of Helmstedt, in Lower Saxony, Germany. The current population is 11,539 and is situated approximately southwest of Wolfsburg, and Braunschweig.

The municipality received the name of Lehre on June 10, 88 ...

– 26 November 1822, in Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

) was a Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

n statesman and Prime Minister of Prussia. While during his late career he acquiesced to reactionary policies, earlier in his career he implemented a variety of Liberal reforms

The Liberal welfare reforms (1906–1914) were a series of acts of social legislation passed by the Liberal Party after the 1906 general election. They represent the emergence of the modern welfare state in the United Kingdom. The reforms demons ...

. To him and Baron vom Stein, Prussia was indebted for improvements in its army system, the abolition of serfdom and feudal burdens, the throwing open of the civil service to all classes, and the complete reform of the educational system.

Family

Hardenberg was the eldest son of Christian Ludwig von Hardenberg (1700-1781), a Hanoverian colonel, later to become field marshal and commander-in-chief of the

Hardenberg was the eldest son of Christian Ludwig von Hardenberg (1700-1781), a Hanoverian colonel, later to become field marshal and commander-in-chief of the Hanoverian army

The House of Hanover (german: Haus Hannover), whose members are known as Hanoverians, is a European royal house of German origin that ruled Hanover, Great Britain, and Ireland at various times during the 17th to 20th centuries. The house ori ...

under King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

from 1776 until his death. The mother was Anna Sophia Ehrengart von Bülow. He was born, one of 8 children, at Essenrode Manor

The Essenrode Manor in Essenrode, a town within the municipality of Lehre, Lower Saxony, was built by Gotthart Heinrich August von Bülow in 1738.

Description

The mansion is built in a late Baroque style surrounded by a small English-style park ...

near Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, his maternal grandfather's estate. The ancestral home of the ''knights of Hardenberg'' is Hardenberg Castle at Nörten-Hardenberg

Nörten-Hardenberg ( Eastphalian: ''Nörten-Harenbarg'') is a municipality in the district of Northeim, in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Geography

It is situated on the river Leine, approx. 10 km southwest of Northeim, and 10 km north of G� ...

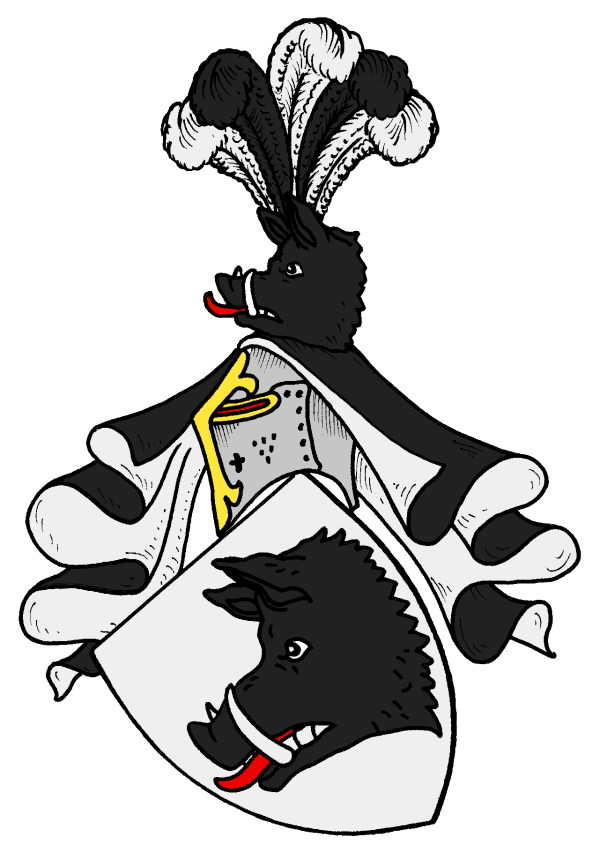

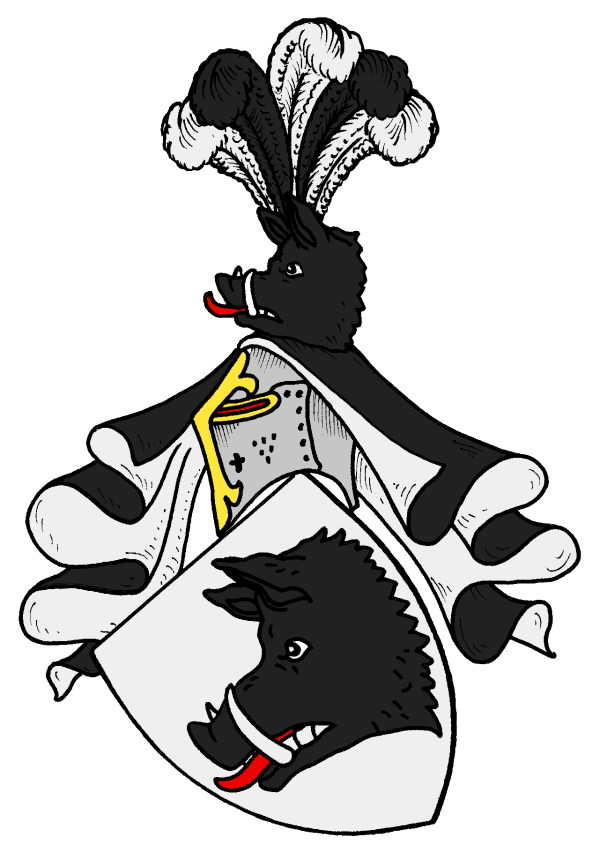

, which the family acquired in 1287 and owns to this day. They were created barons and, in 1778, counts.

Early life

After studying atLeipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

and Göttingen

Göttingen (, , ; nds, Chöttingen) is a university city in Lower Saxony, central Germany, the capital of the eponymous district. The River Leine runs through it. At the end of 2019, the population was 118,911.

General information

The ori ...

, he entered the Hanoverian civil service in 1770 as councillor of the board of domains (''Kammerrat''); but, finding his advancement slow, he set out, on the advice of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, on a series of travels. He spent spending some time at Wetzlar

Wetzlar () is a city in the state of Hesse, Germany. It is the twelfth largest city in Hesse with currently 55,371 inhabitants at the beginning of 2019 (including second homes). As an important cultural, industrial and commercial center, the un ...

, Regensburg (where he studied the mechanism of the Imperial government), Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

. He also visited France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

and Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, where he was received kindly by the King. On his return, he married, at his father's suggestion, the Countess Christiane von Reventlow

Reventlow is the name of a Holstein and Mecklenburg Dano-German noble family, which belongs to the Equites Originarii Schleswig-Holstein. Alternate spellings include Revetlo, Reventlo, Reventlau, Reventlou, Reventlow, Refendtlof and Reffentloff ...

(1759–1793) in 1774. They had a son, Christian Heinrich August Graf von Hardenberg-Reventlow (1775–1841), and a daughter, Lucie von Hardenberg-Reventlow (1776-1854).

In 1778, Hardenberg was raised to the rank of privy councillor and created a graf

(feminine: ) is a historical title of the German nobility, usually translated as "count". Considered to be intermediate among noble ranks, the title is often treated as equivalent to the British title of "earl" (whose female version is "coun ...

(or count). He went back to England, in the hope of obtaining the post of Hanoverian envoy in London; but his wife began an affair with the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

, which created so great a scandal that he was forced to leave the Hanoverian service. In 1782 he entered the service of the Duke of Brunswick, and as president of the board of domains displayed a zeal for reform, in the manner approved by the enlightened despot

Enlightened absolutism (also called enlightened despotism) refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhanc ...

s of the century, which rendered him very unpopular with the orthodox clergy and the conservative estates. In Brunswick, too, his position was in the end made untenable by the conduct of his wife, whom he now divorced. He shortly afterwards married a divorced woman.

Administrator of Ansbach and Bayreuth

Fortunately for Hardenberg, this coincided with the lapsing of the principalities ofAnsbach

Ansbach (; ; East Franconian: ''Anschba'') is a city in the German state of Bavaria. It is the capital of the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Ansbach is southwest of Nuremberg and north of Munich, on the river Fränkische Rezat, ...

and Bayreuth to Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, owing to the resignation of the last margrave, Charles Alexander, in 1791. Hardenberg, who happened to be in Berlin at the time, was appointed administrator of the principalities in 1792, on the recommendation of Ewald Friedrich von Hertzberg

Ewald Friedrich Graf von Hertzberg (2 September 172522 May 1795) was a Prussian statesman.

Early life

Hertzberg, who came of a noble family which had been settled in Pomerania since the 13th century, was born at Lottin (present-day Lotyń, a p ...

. The position, owing to the singular overlapping of territorial claims in the old Empire, was one of considerable delicacy, and Hardenberg filled it with great skill, doing much to reform traditional anomalies and to develop the country, and at the same time labouring to expand the influence of Prussia in southern Germany.

Prussian envoy

After the outbreak of theFrench Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

, his diplomatic ability led to his appointment as Prussian envoy, with a roving commission A roving commission details the duties of a commissioned officer or other official whose responsibilities are neither geographically nor functionally limited.

Where an individual in an official position is given more freedom than would regularly be ...

to visit the Rhenish courts and win them over to Prussia's views. Ultimately, when the necessity for making peace with the French Republic had been recognised, he was appointed to succeed Count Goltz as Prussian plenipotentiary at Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

(28 February 1795), where he signed the treaty of peace. In 1796, his daughter Lucie married Karl Theodor, count of Pappenheim

Pappenheim is a town in the Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen district, in Bavaria, Germany. It is situated on the river Altmühl, 11 km south of Weißenburg in Bayern.

History

Historically, Pappenheim was a statelet within Holy Roman Empire. It ...

(whom she divorced in 1817 to become the wife of Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau).

Prussian cabinet

In 1797, on the accession of King Frederick William III of Prussia, Hardenberg was summoned to Berlin, where he received an important position in the cabinet and was appointed chief of the departments of Magdeburg and Halberstadt, for Westphalia, and for the principality of Neuchâtel. In 1793, Hardenberg had struck up a friendship with Count Haugwitz, the influential minister for foreign affairs, and when in 1803 the latter went away on leave (August–October), he appointed Hardenberg his ''locum tenens

A locum, or locum tenens, is a person who temporarily fulfills the duties of another; the term is especially used for physicians or clergy. For example, a ''locum tenens physician'' is a physician who works in the place of the regular physician. ...

''. It was a critical period since Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

had just occupied Hanover, and Haugwitz had urged upon the king the necessity for strong measures and the expediency of a Russian alliance. During Haugwitz's absence, however, the king's irresolution continued, and he clung to the policy of neutrality, which had so far seemed to have served Prussia so well. Hardenberg contented himself with adapting himself to the royal will. When Haugwitz had returned, the unyielding attitude of Napoleon had caused the king to make advances to Russia, but the mutual declarations of 3 and 25 May 1804 pledged both powers to take up arms only in the event of a French attack upon Prussia or of further aggressions in northern Germany. Finally, Haugwitz, unable to persuade the cabinet to a more vigorous policy, resigned, and on 14 April 1804, Hardenberg succeeded him as foreign minister.

Prussian foreign minister

If there was to be war, Hardenberg would have preferred the French alliance, the price that Napoleon demanded for the cession of Hanover to Prussia, but the eastern powers would not freely have conceded so great an augmentation of Prussian power. However, he still hoped to gain the coveted prize by diplomacy, backed by the veiled threat of an armed neutrality. Then came Napoleon's contemptuous violation of Prussian territory by marching three French corps through Ansbach. King Frederick William's pride overcame his weakness, and on November 3, he signed with TsarAlexander I of Russia

Alexander I (; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first King of Congress Poland from 1815, and the Grand Duke of Finland from 1809 to his death. He was the eldest son of Emperor Paul I and Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg.

The son o ...

the terms of an ultimatum to be laid before the French emperor.

Haugwitz was despatched to Vienna with the document, but before he had arrived, the Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz i ...

had been fought, and the Prussian plenipotentiary had to make terms with Napoleon. Prussia, by the treaty signed at Schönbrunn on 15 December 1805, received Hanover but in return for all her territories in South Germany. One condition of the arrangement was the retirement of Hardenberg, whom Napoleon disliked. He was again foreign minister for a few months after the crisis of 1806 (April–July 1807), but Napoleon's resentment was implacable, and one of the conditions of the terms granted to Prussia by the Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

was Hardenberg's dismissal.

Prussian chancellor

After the enforced retirement ofStein

Stein is a German, Yiddish and Norwegian word meaning "stone" and "pip" or "kernel". It stems from the same Germanic root as the English word stone. It may refer to:

Places In Austria

* Stein, a neighbourhood of Krems an der Donau, Lower Aust ...

in 1810 and the unsatisfactory interlude of the feeble Altenstein ministry, Hardenberg was again summoned to Berlin, this time as chancellor (6 June 1810). The campaign of Jena and its consequences had had a profound effect upon him, and in his mind, the traditions of the old diplomacy had given place to the new sentiment of nationality characteristic of the coming age, which in him found expression in a passionate desire to restore the position of Prussia and crush her oppressors. During his retirement at Riga, he had worked out an elaborate plan for reconstructing the monarchy on liberal lines, and when he came into power, the circumstances of the time did not admit of his pursuing an independent foreign policy, but he steadily prepared for the struggle with France by carrying out Stein's far-reaching schemes of social and political reorganization.

Reforms

The military system was completely reformed, serfdom was abolished, municipal institutions were fostered, the civil service was thrown open to all classes and great attention was devoted to the educational needs of every section of the community. When at last the time came to put the reforms to the test, after the Moscow campaign of 1812, it was Hardenberg who persuaded Frederick William to take advantage of General Yorck's loyal disloyalty and to declare against France. He was rightly regarded by German patriots as the statesman who had done most to encourage the spirit of national independence, and immediately after he had signed the first Peace of Paris, he was raised to the rank of prince (3 June 1814) in recognition of the part he had played in theWar of Liberation

Wars of national liberation or national liberation revolutions are conflicts fought by nations to gain independence. The term is used in conjunction with wars against foreign powers (or at least those perceived as foreign) to establish separat ...

.

Metternich's shadow

Hardenberg now had a position in that close corporation of sovereigns and statesmen by whom Europe was governed. He accompanied the allied sovereigns to England and at theCongress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

(1814–1815) was the chief representative of Prussia. However, the zenith of his influence, if not of his fame, had passed. In diplomacy, he was no match for Klemens von Metternich, whose influence soon overshadowed his own in the councils of Europe, Germany and ultimately even Prussia itself. At Vienna, in spite of the powerful backing of Alexander of Russia, he failed to secure the annexation of the whole of Saxony to Prussia. At Paris, after Waterloo, he failed to carry through his views as to the further dismemberment of France and had weakly allowed Metternich to forestall him in making terms with the states of the Confederation of the Rhine, which secured to Austria the preponderance in the German federal diet. On the eve of the conference of Carlsbad (1819) he signed a convention with Metternich in which, according the historian Heinrich von Treitschke

Heinrich Gotthard Freiherr von Treitschke (; 15 September 1834 – 28 April 1896) was a German historian, political writer and National Liberal member of the Reichstag during the time of the German Empire. He was an extreme nationalist, who favo ...

, 'like a penitent sinner, without any formal quid pro quo, the monarchy of Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

yielded to a foreign power a voice in her internal affairs."

At the congresses of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen), Troppau

Opava (; german: Troppau, pl, Opawa) is a city in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 55,000 inhabitants. It lies on the river Opava. Opava is one of the historical centres of Silesia. It was a historical capital o ...

, Laibach

Laibach () is a Slovenian avant-garde music group associated with the industrial, martial, and neo-classical genres. Formed in the mining town of Trbovlje (at the time in Yugoslavia) in 1980, Laibach represents the musical wing of the Neue ...

and Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

, the voice of Hardenberg was but an echo of that of Metternich. The cause lay partly in the difficult circumstances of the loosely-knit Prussian monarchy but partly in Hardenberg's character had never been well balanced but had deteriorated with age. He continued amiable, charming and enlightened as ever, but the excesses that had been pardonable in a young diplomat were a scandal in an elderly chancellor and could not but weaken his influence with so pious a ''Landesvater'' as Frederick William III.

To overcome the king's terror of liberal experiments would have needed all the powers of an adviser at once wise and in character wholly trustworthy. Hardenberg was wise enough and saw the necessity for constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

al reform, but he clung with almost senile tenacity to the sweets of office, and when the tide turned against liberalism, he allowed himself to drift with it. In the privacy of royal commissions, he continued to elaborate schemes for constitutions that never saw the light, but Germany, disillusioned, regarded him as an adherent of Metternich, an accomplice in the policy of the Carlsbad Decrees and the Troppau Protocol.

In 1814, King Frederick William III vested Hardenberg with the locality of Quilitz, together with the princely title, as a gratification for his merits as Prussian state chancellor. When he received the manor, he renamed the place right away into ''

In 1814, King Frederick William III vested Hardenberg with the locality of Quilitz, together with the princely title, as a gratification for his merits as Prussian state chancellor. When he received the manor, he renamed the place right away into ''Neuhardenberg

Neuhardenberg is a municipality in the district Märkisch-Oderland, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the site of Neuhardenberg Palace, residence of the Prussian statesman Prince Karl August von Hardenberg (1750-1822). The municipal area comprises th ...

(New Hardenberg)''. From 1820 on, he had the mansion and the church rebuilt in neoclassical style

Neoclassical architecture is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy and France. It became one of the most prominent architectural styles in the Western world. The prevailing sty ...

, according to plans designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Karl Friedrich Schinkel (13 March 1781 – 9 October 1841) was a Prussian architect, city planner and painter who also designed furniture and stage sets. Schinkel was one of the most prominent architects of Germany and designed both neoclassic ...

, while the gardens were redesigned by his son-in-law, Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau, and Peter-Joseph Lenné.

Hardenberg died at Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

soon after the closing of the Congress of Verona. Hardenberg's ''Memoirs, 1801-07'' were suppressed for 50 years after which they were edited with a biography by Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis of ...

and published as ''Denkwürdigkeiten des Fürsten von Hardenberg'' (5 vols., Leipzig, 1877).

Notes

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hardenberg, Karl August 1750 births 1822 deaths People from Helmstedt (district) German princes German politicians of the Napoleonic Wars People from the Electorate of Hanover Prussian diplomats Prussian nobility Prussian politicians Karl August Foreign ministers of Prussia Interior ministers of Prussia Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Poland) H