July 1962 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The following events occurred in July 1962:

The following events occurred in July 1962:

*

*

*Irish broadcaster

*Irish broadcaster

*

*

The following events occurred in July 1962:

The following events occurred in July 1962:

July 1

Events Pre-1600

* 69 – Tiberius Julius Alexander orders his Roman legions in Alexandria to swear allegiance to Vespasian as Emperor.

* 552 – Battle of Taginae: Byzantine forces under Narses defeat the Ostrogoths in Italy, and th ...

, 1962 (Sunday)

Rwanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator ...

and Burundi

Burundi (, ), officially the Republic of Burundi ( rn, Repuburika y’Uburundi ; Swahili: ''Jamuhuri ya Burundi''; French: ''République du Burundi'' ), is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley at the junction between the African Gr ...

, the northern and southern portions of Ruanda-Urundi

Ruanda-Urundi (), later Rwanda-Burundi, was a colonial territory, once part of German East Africa, which was occupied by troops from the Belgian Congo during the East African campaign in World War I and was administered by Belgium under milita ...

, were both granted independence from Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

on the same day. Grégoire Kayibanda

Grégoire Kayibanda (1 May 192415 December 1976) was a Rwandan politician and revolutionary who was the first elected President of Rwanda from 1962 to 1973. An ethnic Hutu, he was a pioneer of the Rwandan Revolution and led Rwanda's struggle fo ...

of the Hutu

The Hutu (), also known as the Abahutu, are a Bantu ethnic or social group which is native to the African Great Lakes region. They mainly live in Rwanda, Burundi and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, where they form one of the p ...

tribe was sworn in as President of Rwanda

This article lists the presidents of Rwanda since the creation of the office in 1961 (during the Rwandan Revolution), to the present day.

The president of Rwanda is the head of state and head of executive of the Republic of Rwanda. The pres ...

at Kigali

Kigali () is the capital and largest city of Rwanda. It is near the nation's geographic centre in a region of rolling hills, with a series of valleys and ridges joined by steep slopes. As a primate city, Kigali has been Rwanda's economic, cult ...

, and Mwambutsa IV, who had reigned as the titular leader of the Tutsi

The Tutsi (), or Abatutsi (), are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. They are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi (the other two being the largest Bantu ethnic g ...

tribe since 1915, continued as King of Burundi.

* The Treaty of Nordic Cooperation of Helsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the Capital city, capital, primate city, primate, and List of cities and towns in Finland, most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of U ...

(signed 23 March 1962) came into force.

* Supporters of Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n independence won a 90% majority in a referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a Representative democr ...

.

* Bruce McLaren

Bruce Leslie McLaren (30 August 1937 – 2 June 1970) was a New Zealand racing car designer, driver, engineer, and inventor.

His name lives on in the McLaren team which has been one of the most successful in Formula One championship history, ...

won the 1962 Reims Grand Prix

The 3rd Reims Grand Prix was a Formula One motor race, held on July 1, 1962, at the Reims-Gueux circuit, near Reims in France. The race was run over 50 laps of the 8.302 km circuit and was won by New Zealand driver Bruce McLaren in a Cooper ...

. McClaren of New Zealand, a former rugby player turned race car driver, finished the course in 2 hours, 2 seconds.

* The first Canadian Medicare plan was launched in Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

, resulting in the Saskatchewan doctors' strike The Saskatchewan doctors' strike was a 23-day labour action exercised by medical doctors in 1962 in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan in an attempt to force the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation government of Saskatchewan to drop its program ...

. Thousands of citizens joined the protests against compulsory health care ten days later.

* Relocation of the Manned Spacecraft Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

from Langley Field Langley may refer to:

People

* Langley (surname), a common English surname, including a list of notable people with the name

* Dawn Langley Simmons (1922–2000), English author and biographer

* Elizabeth Langley (born 1933), Canadian perfo ...

to Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, was completed.

* Julio Adalberto Rivera Carballo

Julio Adalberto Rivera Carballo (2 September 1921 – 29 July 1973) was a Salvadoran politician and military officer, who was the 34th President of El Salvador, in office from 1962 to 1967.

Early life and career

Rivera was born in Zacatecol ...

became President of El Salvador. He had been the only candidate in elections on April 30.

* Died: Bidhan Chandra Roy

Bidhan Chandra Roy (1 July 1882 – 1 July 1962) was an Indian physician, educationist, and statesman who served as Chief Minister of West Bengal from 1948 until his death in 1962. Roy played a key role in the founding of several institutio ...

, 80, Indian politician and Chief Minister of West Bengal

The Chief Minister of West Bengal is the representative of the Government of India in the state of West Bengal and the head of the executive branch of the Government of West Bengal. The chief minister is head of the Council of Ministers and ap ...

since 1948.

July 2

Events Pre-1600

* 437 – Emperor Valentinian III begins his reign over the Western Roman Empire. His mother Galla Placidia ends her regency, but continues to exercise political influence at the court in Rome.

* 626 – Li Shimin, t ...

, 1962 (Monday)

* Sam Walton

Samuel Moore Walton (March 29, 1918 – April 5, 1992)

was an American business magnate best known for founding the retailers Walmart and Sam's Club, which he started in 1962 and 1983 respectively. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. grew to be the world's ...

opened the first Walmart

Walmart Inc. (; formerly Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.) is an American multinational retail corporation that operates a chain of hypermarkets (also called supercenters), discount department stores, and grocery stores from the United States, headquarter ...

store as Wal-Mart Discount City in Rogers, Arkansas

Rogers is a city in Benton County, Arkansas, United States. Located in the Ozarks, it is part of the Northwest Arkansas region, one of the fastest growing metro areas in the country. Rogers was the location of the first Walmart store, whose cor ...

, United States. By 1970, there would be 38 Wal-Mart stores. After 50 years, there were more than 9,766 stores in 27 countries, and 11,766 by mid-2019.

* Simulated off-the-pad Gemini ejection tests began at Naval Ordnance Test Station

Naval Air Weapons Station (NAWS) China Lake is a large military installation in California that supports the research, testing and evaluation programs of the United States Navy. It is part of Navy Region Southwest under Commander, Navy Installat ...

. Five ejections were completed by the first week of August. The tests revealed difficulties which led to two important design changes: the incorporation of a drogue-gun method of deploying the personnel parachute and the installation of a three-point restraint-harness-release system similar to those used in military aircraft. On August 6-7, representatives of Manned Spacecraft Center and ejection system contractors met to review the status of ejection seat

In aircraft, an ejection seat or ejector seat is a system designed to rescue the pilot or other crew of an aircraft (usually military) in an emergency. In most designs, the seat is propelled out of the aircraft by an explosive charge or rock ...

design and the development test program. They decided that off-the-pad ejection tests would not be resumed until ejection seat hardware reflected all major anticipated design features and the personnel parachute had been fully tested. Design changes were checked out in a series of bench and ground firings, concluding on August 30 with a successful inflight drop test of a seat and dummy. Off-the-pad testing resumed in September.

July 3

Events Pre-1600

* 324 – Battle of Adrianople: Constantine I defeats Licinius, who flees to Byzantium.

* 987 – Hugh Capet is crowned King of France, the first of the Capetian dynasty that would rule France until the French Revolut ...

, 1962 (Tuesday)

* The 1962 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships

The 15th Artistic Gymnastics World Championships were held on July 3–8, 1962 in Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia, this being the 3rd time that Prague hosted these championships.

These were the last championships China competed in until 19 ...

opened in Prague and ran until July 8.

* France and its President, Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

, recognized the independence of Algeria, with the signing of the declaration at a meeting of the French Cabinet.

* The Chichester Festival Theatre

Chichester Festival Theatre is a theatre and Grade II* listed building situated in Oaklands Park in the city of Chichester, West Sussex, England. Designed by Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya, it was opened by its founder Leslie Evershed-Mart ...

, Britain's first large modern theatre with a thrust stage, opened. Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

was the first artistic director.

* Gemini Project Office met with representatives of Manned Spacecraft Center's Flight Operations Divisions, McDonnell

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer based in St. Louis, Missouri. The company was founded on July 6, 1939, by James Smith McDonnell, and was best known for its military fighters, including the F-4 Phantom II ...

, International Business Machines, Aerospace

Aerospace is a term used to collectively refer to the atmosphere and outer space. Aerospace activity is very diverse, with a multitude of commercial, industrial and military applications. Aerospace engineering consists of aeronautics and ast ...

, Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an ...

Space Systems Division

Space Systems Command (SSC) is the United States Space Force's space development, acquisition, launch, and logistics field command. It is headquartered at Los Angeles Air Force Base, California and manages the United States' space launc ...

, Lockheed, Martin Martin may refer to:

Places

* Martin City (disambiguation)

* Martin County (disambiguation)

* Martin Township (disambiguation)

Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Austr ...

, Space Technology Laboratories, Inc. (Redondo Beach, California

Redondo Beach (Spanish for ''round'') is a coastal city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, located in the South Bay region of the Greater Los Angeles area. It is one of three adjacent beach cities along the southern portion of Sa ...

), and Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville postal address), is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. As the largest NASA center, MSFC's firs ...

to outline the work to be done before final mission planning. A center coordinating group, with two representatives from each agency, was established.

* Born:

**Tom Cruise

Thomas Cruise Mapother IV (born July 3, 1962), known professionally as Tom Cruise, is an American actor and producer. One of the world's highest-paid actors, he has received various accolades, including an Honorary Palme d'Or and three Go ...

, American film actor known for ''Risky Business

''Risky Business'' is a 1983 American teen comedy-drama film written and directed by Paul Brickman (in his directorial debut) and starring Tom Cruise and Rebecca De Mornay. Best known as Cruise's breakout film, ''Risky Business'' was a critica ...

'', ''Jerry Maguire

''Jerry Maguire'' is a 1996 American romantic comedy-drama sports film written, produced, and directed by Cameron Crowe; it stars Tom Cruise, Cuba Gooding Jr., Renée Zellweger, and Regina King. Produced in part by James L. Brooks, it was ins ...

'' and the ''Mission: Impossible'' film series; as Thomas Cruise Mapother IV, in Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, and Rochester.

At the 2020 census, the city' ...

**Thomas Gibson

Thomas Ellis Gibson (born July 3, 1962) is an American actor and director. He is best known for his television roles as Daniel Nyland on ''Chicago Hope'' (1994–1997), Greg Montgomery on ''Dharma & Greg'' (1997–2002) and Aaron Hotchner on ''C ...

, American actor, in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

July 4

Events Pre-1600

*362 BC – Battle of Mantinea: The Thebans, led by Epaminondas, defeated the Spartans.

* 414 – Emperor Theodosius II, age 13, yields power to his older sister Aelia Pulcheria, who reigned as regent and proclaimed ...

, 1962 (Wednesday)

* The Burma Socialist Programme Party

The Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), ; abbreviated , was Burma's ruling party from 1962 to 1988 and sole legal party from 1964 to 1988. Party chairman Ne Win overthrew the country's democratically elected government in a coup d'ét ...

was established by Ne Win

Ne Win ( my, နေဝင်း ; 10 July 1910, or 14 or 24 May 1911 – 5 December 2002) was a Burmese politician and military commander who served as Prime Minister of Burma from 1958 to 1960 and 1962 to 1974, and also President of Burma ...

's military regime.

* Born:

**Neil Morrissey

Neil Anthony Morrissey (born 4 July 1962) is an English actor. He is known for his role as Tony in '' Men Behaving Badly''. Other notable acting roles include Deputy Head Eddie Lawson in the BBC One school-based drama series '' Waterloo Road'' ...

, English comedian and actor; in Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in th ...

, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands C ...

**Pam Shriver

Pamela Howard Shriver (born July 4, 1962) is an American former professional tennis player and current tennis broadcaster and pundit. During the 1980s and 1990s, Shriver won 133 titles, including 21 singles titles, 111 women's doubles titles, an ...

, American tennis player, winner of multiple women's doubles championships with Martina Navratilova; in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

July 5

Events Pre-1600

* 328 – The official opening of Constantine's Bridge built over the Danube between Sucidava (Corabia, Romania) and Oescus ( Gigen, Bulgaria) by the Roman architect Theophilus Patricius.

* 1316 – The Burgundian a ...

, 1962 (Thursday)

* After Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

's independence was recognized by France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Oran massacre took place at Oran, the section of Algiers where most French Algerians lived. The official estimate of the death toll was 20 French Algerians and 75 Algerians killed.

* The French Assembly voted 241–72 to remove the immunity against arrest and prosecution that former Prime Minister Georges Bidault

Georges-Augustin Bidault (; 5 October 189927 January 1983) was a French politician. During World War II, he was active in the French Resistance. After the war, he served as foreign minister and prime minister on several occasions. He joined the ...

had in April 1961, when he called for the overthrow of President Charles De Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

, clearing the way for indictment of Bidault for treason. Bidault had fled to exile in Italy.

July 6

Events Pre-1600

* 371 BC – The Battle of Leuctra shatters Sparta's reputation of military invincibility.

* 640 – Battle of Heliopolis: The Muslim Arab army under 'Amr ibn al-'As defeat the Byzantine forces near Heliopolis (Egypt ...

, 1962 (Friday)

Gay Byrne

Gabriel Mary "Gay" Byrne (5 August 1934 – 4 November 2019) was an Irish presenter and host of radio and television. His most notable role was first host of '' The Late Late Show'' over a 37-year period spanning 1962 until 1999. ''The Late Lat ...

presented his first edition of '' The Late Late Show''. Byrne would go on to present the talk show

A talk show (or chat show in British English) is a television programming or radio programming genre structured around the act of spontaneous conversation.Bernard M. Timberg, Robert J. Erler'' (2010Television Talk: A History of the TV Talk Sh ...

for 37 years, making him the longest-running TV talk show host in history.

*Martin Martin may refer to:

Places

* Martin City (disambiguation)

* Martin County (disambiguation)

* Martin Township (disambiguation)

Antarctica

* Martin Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land

* Port Martin, Adelie Land

* Point Martin, South Orkney Islands

Austr ...

prepared a plan for flight testing the malfunction detection system (MDS) for the Gemini launch vehicle on development flights of the Titan II

The Titan II was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) developed by the Glenn L. Martin Company from the earlier Titan I missile. Titan II was originally designed and used as an ICBM, but was later adapted as a medium-lift space l ...

weapon system. Gemini Project Office (GPO) had requested Martin to prepare Systems Division and Aerospace approved the plan and won GPO concurrence early in August. This so-called "piggyback plan" required installing the Gemini MDS in Titan II engines on six Titan II flights to demonstrate its reliability before it was flown on Gemini.

*The {{Convert, 320, ft, m, adj=on deep Sedan Crater

Sedan Crater is the result of the Sedan nuclear test and is located within the Nevada Test Site, southwest of Groom Lake, Nevada (Area 51). The crater was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 21, 1994.

The crater is the r ...

, measuring {{Convert, 1280, ft, m in diameter, was created in less than a split second in Nye County, Nevada

Nye County is a county in the U.S. state of Nevada. As of the 2020 census, the population was 51,591. Its county seat is Tonopah. At , Nye is Nevada's largest county by area and the third-largest county in the contiguous United States, beh ...

, with an underground nuclear test

Underground nuclear testing is the Nuclear weapons testing, test detonation of nuclear weapons that is performed underground. When the device being tested is buried at sufficient depth, the nuclear explosion may be contained, with no release of ...

. The fallout exposed 13 million Americans to radiation; regular monthly tours are now given of the crater, which ceased being radioactive after less than a year.

* Died:

** Roger Degueldre, 37, former French Army officer who rebelled to form the OAS Delta Commandos, was executed by firing squad

**William Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most o ...

, 64, American novelist and 1950 Nobel laureate

July 7

Events Pre-1600

* 1124 – The city of Tyre falls to the Venetian Crusade after a siege of nineteen weeks.

* 1456 – A retrial verdict acquits Joan of Arc of heresy 25 years after her execution.

* 1520 – Spanish ''conquistad ...

, 1962 (Saturday)

* Alitalia Flight 771 crashed into a hill about {{convert, 84, km, mi north-east of Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the secon ...

, killing all 94 people aboard.

* A Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-152 set a new airspeed record of 2,681 km/h (1,666 mph).

* In Burma, the government of General Ne Win

Ne Win ( my, နေဝင်း ; 10 July 1910, or 14 or 24 May 1911 – 5 December 2002) was a Burmese politician and military commander who served as Prime Minister of Burma from 1958 to 1960 and 1962 to 1974, and also President of Burma ...

forcibly broke up a demonstration at Rangoon University

'')

, mottoeng = There's no friend like wisdom.

, established =

, type = Public

, rector = Dr. Tin Mg Tun

, undergrad = 4194

, postgrad = 5748

, city = Kamayut 11041, Yangon

, state = Yangon Regio ...

, killing 15 students and wounding 27.

July 8

Events Pre-1600

* 1099 – Some 15,000 starving Christian soldiers begin the siege of Jerusalem by marching in a religious procession around the city as its Muslim defenders watch.

*1283 – Roger of Lauria, commanding the Aragonese ...

, 1962 (Sunday)

* In the most important symbolic gesture of post-war French-German unity, President Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

of France and Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

of West Germany, both devout Catholics, attended mass at the Reims Cathedral

, image = Reims Kathedrale.jpg

, imagealt = Facade, looking northeast

, caption = Façade of the cathedral, looking northeast

, pushpin map = France

, pushpin map alt = Location within France

, ...

and prayed together. The Cathedral was where the Emperor common to both nations, Carolus Magnus (Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first E ...

in France and Karl der Große in Germany)— had been baptized at Reims.

* The 1962 French Grand Prix

The 1962 French Grand Prix was a Formula One motor race held at Rouen-Les-Essarts on 8 July 1962. It was race 4 of 9 in both the 1962 World Championship of Drivers and the 1962 International Cup for Formula One Manufacturers. The race was won by D ...

was held at Rouen-Les-Essarts and won by Dan Gurney

Daniel Sexton Gurney (April 13, 1931 – January 14, 2018) was an American racing driver, race car constructor, and team owner who reached racing's highest levels starting in 1958. Gurney won races in the Formula One, Indy Car, NASCAR, Can-Am, ...

of the United States.

* Born: Joan Osborne

Joan Elizabeth Osborne (born July 8, 1962) is an American singer, songwriter, and interpreter of music, having recorded and performed in various popular American musical genres including rock, pop, soul, R&B, blues, and country. She is best kn ...

, American singer-songwriter; in Anchorage, Kentucky

Anchorage is a home rule-class city in eastern Jefferson County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,348 at the 2010 census and an estimated 2,432 in 2018. It is a suburb of Louisville.

History

The land that is now Anchorage was a p ...

July 9

Events Pre-1600

*118 – Hadrian, who became emperor a year previously on Trajan's death, makes his entry into Rome.

* 381 – The end of the First Council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople by the Roman Emperor Theodos ...

, 1962 (Monday)

* In the Starfish Prime

Starfish Prime was a high-altitude nuclear test conducted by the United States, a joint effort of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the Defense Atomic Support Agency. It was launched from Johnston Atoll on July 9, 1962, and was the larg ...

test, the United States exploded a 1.4 megaton hydrogen bomb in outer space, sending the warhead on a Titan missile to an altitude of {{Convert, 248, mi over Johnston Island

Johnston Atoll is an unincorporated territory of the United States, currently administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Johnston Atoll is a National Wildlife Refuge and part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine Nation ...

. The first two attempts at exploding a nuclear missile above the Earth had failed. The flash was visible in Hawaii, {{Convert, 750, mi away, and scientists discovered the destructive effects of the first major manmade electromagnetic pulse

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP), also a transient electromagnetic disturbance (TED), is a brief burst of electromagnetic energy. Depending upon the source, the origin of an EMP can be natural or artificial, and can occur as an electromagnetic f ...

(EMP), as a surge of electrons burned out streetlights, blew fuses, and disrupted communications. Increasing radiation in some places one hundredfold, the EMP damaged at least ten orbiting satellites beyond repair.

* NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

scientists concluded that the layer of haze reported by astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

s John Glenn

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American Marine Corps aviator, engineer, astronaut, businessman, and politician. He was the third American in space, and the first American to orbit the Earth, circling ...

and Scott Carpenter

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013) was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the Mercury Seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury ...

was a phenomenon called "airglow

Airglow (also called nightglow) is a faint emission of light by a planetary atmosphere. In the case of Earth's atmosphere, this optical phenomenon causes the night sky never to be completely dark, even after the effects of starlight and diffu ...

." Using a photometer

A photometer is an instrument that measures the strength of electromagnetic radiation in the range from ultraviolet to infrared and including the visible spectrum. Most photometers convert light into an electric current using a photoresistor, ...

, Carpenter was able to measure the layer as being 2 degrees wide. Airglow accounts for much of the illumination in the night sky.

* American artist Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol (; born Andrew Warhola Jr.; August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American visual artist, film director, and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art. His works explore the relationsh ...

first presented his ''Campbell's Soup Cans

''Campbell's Soup Cans'' (sometimes referred to as ''32 Campbell's Soup Cans'') is a work of art produced between November 1961 and March or April 1962 by American artist Andy Warhol. It consists of thirty-two canvases, each measuring in he ...

'' at the Ferus Gallery

The Ferus Gallery was a contemporary art gallery which operated from 1957 to 1966. In 1957, the gallery was located at 736-A North La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles, California. In 1958, it was relocated across the street to 723 North La Cienega ...

in Los Angeles.

* Died: Georges Bataille

Georges Albert Maurice Victor Bataille (; ; 10 September 1897 – 9 July 1962) was a French philosopher and intellectual working in philosophy, literature, sociology, anthropology, and history of art. His writing, which included essays, novels ...

, 64, French philosopher and writer, of arteriosclerosis

Arteriosclerosis is the thickening, hardening, and loss of elasticity of the walls of arteries. This process gradually restricts the blood flow to one's organs and tissues and can lead to severe health risks brought on by atherosclerosis, which ...

July 10

Events Pre-1600

*138 – Emperor Hadrian of Rome dies of heart failure at his residence on the bay of Naples, Baiae; he is buried at Rome in the Tomb of Hadrian beside his late wife, Vibia Sabina.

* 645 – Isshi Incident: Prince ...

, 1962 (Tuesday)

* One of the spans in the Kings Bridge in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

, Australia, collapsed after a {{Convert, 45, t, adj=on vehicle passed over it, only 15 months after the multi-lane highway bridge's opening on April 12, 1961. The collapse occurred immediately after the driver of the vehicle had passed over the span, and nobody was hurt.

*

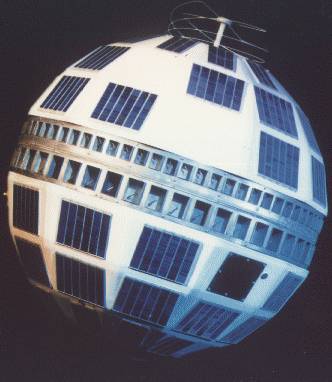

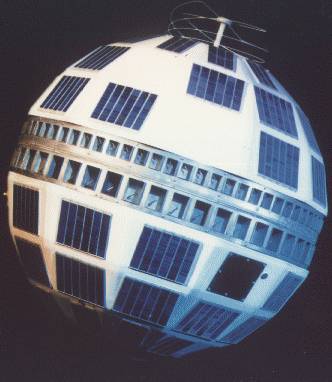

* AT&T

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile ...

's Telstar, the world's first commercial communications satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth ...

, was launched into orbit from Cape Canaveral

, image = cape canaveral.jpg

, image_size = 300

, caption = View of Cape Canaveral from space in 1991

, map = Florida#USA

, map_width = 300

, type = Cape

, map_caption = Location in Florida

, location ...

at 3:35 a.m. local time, and activated that night. The first image transmitted between continents was a black-and-white photo of the American flag sent from the U.S. transmitter at Andover, Maine

Andover is a town in Oxford County, Maine, United States. The population was 752 at the 2020 census. Set among mountains and crossed by the Appalachian Trail, Andover is home to the Lovejoy Covered Bridge and was the site of the Andover Earth ...

, to Pleumeur-Bodou

Pleumeur-Bodou (; ) is a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department of Brittany in northwestern France.

Population

Inhabitants of Pleumeur-Bodou are called ''pleumeurois'' in French.

Sister town

Pleuveur-Bodoù is twinned with Crosshaven, a vi ...

in France.{{cite book , first=John , last=Bray , author-link=John Bray (communications engineer) , title=Innovation and the Communications Revolution: From the Victorian Pioneers to Broadband Internet , publisher=IET , year=2002 , pages=213–214

* The All-Channel Television Receiver Bill was signed into law, requiring that all televisions made in the United States to be able to receive both VHF

Very high frequency (VHF) is the ITU designation for the range of radio frequency electromagnetic waves (radio waves) from 30 to 300 megahertz (MHz), with corresponding wavelengths of ten meters to one meter.

Frequencies immediately below VHF ...

signals (channels 2 to 13 on 30 to 300 MHz) and UHF

Ultra high frequency (UHF) is the ITU designation for radio frequencies in the range between 300 megahertz (MHz) and 3 gigahertz (GHz), also known as the decimetre band as the wavelengths range from one meter to one tenth of a meter (on ...

(channels 14 to 83, on frequencies between 470 and 896 MHz). The result was to open hundreds of new television channels.

* Francisco Brochado de Rocha was approved as the new Prime Minister of Brazil

Historically, the political post of Prime Minister, officially called President of the Council of Ministers ( pt, Primeiro-ministro, Presidente do Conselho de Ministros), existed in Brazil in two different periods: from 1847 to 1889 (during the ...

by a 215-58 vote of Parliament.

* Died: Tommy Milton

Thomas Milton (November 14, 1893 – July 10, 1962) was an American race car driver best known as the first two-time winner of the Indianapolis 500. He was notable for having only one functional eye, a disability that would have disqualified him ...

, 68, American race car driver and first to win the Indianapolis 500 twice (in 1921 and 1923), despite being blind in one eye; shot himself twice after making funeral arrangements for himself; by suicide

July 11

Events Pre-1600

* 472 – After being besieged in Rome by his own generals, Western Roman Emperor Anthemius is captured in St. Peter's Basilica and put to death.

* 813 – Byzantine emperor Michael I, under threat by conspiracies, ...

, 1962 (Wednesday)

* The first person to swim across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

underwater, without surfacing, arrived in Sandwich Bay at Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

18 hours after departing from Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Although Calais is by far the largest city in Pas-de-Calais, the department's prefecture is its third-largest city of Arras. Th ...

. Fred Baldasare wore scuba gear and was assisted by a guiding ship and the use of oxygen tanks.

* NASA officials announced the basic decision for the crewed lunar exploration program that Project Apollo should proceed using the lunar orbit rendezvous

Lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) is a process for landing humans on the Moon and returning them to Earth. It was utilized for the Apollo program missions in the 1960s and 1970s. In a LOR mission, a main spacecraft and a smaller lunar lander travel to ...

as the prime mission mode. Based on more than a year of intensive study, this decision for the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR), rather than for the alternative direct ascent

Direct ascent is a method of landing a spacecraft on the Moon or another planetary surface directly, without first assembling the vehicle in Earth orbit, or carrying a separate landing vehicle into orbit around the target body. It was proposed as ...

or earth orbit rendezvous modes, enabled immediate planning, research and development, procurement, and testing programs for the next phase of American space exploration

Space exploration is the use of astronomy and space technology to explore outer space. While the exploration of space is carried out mainly by astronomers with telescopes, its physical exploration though is conducted both by uncrewed robo ...

to proceed on a firm basis.

* The capability for successfully accomplishing water landings with either the parachute landing system or the paraglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or lies supine in a cocoon-like ...

landing system was established as a firm requirement for the Gemini spacecraft

Project Gemini () was NASA's second human spaceflight program. Conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, Gemini started in 1961 and concluded in 1966. The Gemini spacecraft carried a two-astronaut crew. Ten Gemini crews and 16 individual ...

. The spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle or machine designed to fly in outer space. A type of artificial satellite, spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including communications, Earth observation, meteorology, navigation, space colonization, ...

would be required to provide for the safety of the crew and to be seaworthy during a water landing and a 36-hour postlanding period.

* Born: Pauline McLynn

Pauline McLynn (born 11 July 1962) is an Irish character actress and author. She is best known for her roles as Mrs Doyle in the Channel 4 sitcom ''Father Ted'', Libby Croker in the Channel 4 comedy drama '' Shameless'', Tip Haddem in the BBC ...

, Irish comedian and TV actress known for ''Father Ted

''Father Ted'' is a sitcom created by Irish writers Graham Linehan and Arthur Mathews and produced by British production company Hat Trick Productions for Channel 4. It aired over three series from 21 April 1995 until 1 May 1998, includin ...

''; in Sligo

Sligo ( ; ga, Sligeach , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of approximately 20,000 in 2016, it is the largest urban ce ...

, County Sligo

County Sligo ( , gle, Contae Shligigh) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the Border Region and is part of the province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in the county. Sligo County Council is the local ...

* Died:

**René Maison

René Maison (24 November 1895 – 11 July 1962) was a prominent Belgian operatic tenor, particularly associated with heroic roles of the French, Italian and German repertories.

Career

Born in Frameries, Belgium, he studied in Brussels and Par ...

, 66, Belgian operatic tenor

**Owen D. Young

Owen D. Young (October 27, 1874July 11, 1962) was an American industrialist, businessman, lawyer and diplomat at the Second Reparations Conference (SRC) in 1929, as a member of the German Reparations International Commission.

He is known for th ...

, 87, American businessman who founded Radio Corporation of America

The RCA Corporation was a major American electronics company, which was founded as the Radio Corporation of America in 1919. It was initially a patent trust owned by General Electric (GE), Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Com ...

(RCA) and co-founded the National Broadcasting Company

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters ar ...

(NBC)

July 12

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – The armies of Titus attack the walls of Jerusalem after a six-month siege. Three days later they breach the walls, which enables the army to destroy the Second Temple.

* 927 – King Constantine I ...

, 1962 (Thursday)

* The Rolling Stones

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. Active for six decades, they are one of the most popular and enduring bands of the rock era. In the early 1960s, the Rolling Stones pioneered the gritty, rhythmically d ...

made their debut at London's Marquee Club

The Marquee Club was a music venue first located at 165 Oxford Street in London, when it opened in 1958 with a range of jazz and skiffle acts. Its most famous period was from 1964 to 1988 at 90 Wardour Street in Soho, and it finally closed ...

, Number 165 Oxford Street, opening for the first time under that name, for Long John Baldry

John William "Long John" Baldry (12 January 1941 – 21 July 2005) was an English musician and actor. In the 1960s, he was one of the first British vocalists to sing the blues in clubs and shared the stage with many British musicians including ...

. Mick Jagger

Sir Michael Philip Jagger (born 26 July 1943) is an English singer and songwriter who has achieved international fame as the lead vocalist and one of the founder members of the rock band the Rolling Stones. His ongoing songwriting partnershi ...

, Brian Jones

Lewis Brian Hopkin Jones (28 February 1942 – 3 July 1969) was an English multi-instrumentalist and singer best known as the founder, rhythm/lead guitarist, and original leader of the Rolling Stones. Initially a guitarist, he went on to prov ...

, Keith Richards

Keith Richards (born 18 December 1943), often referred to during the 1960s and 1970s as "Keith Richard", is an English musician and songwriter who has achieved international fame as the co-founder, guitarist, secondary vocalist, and co-princi ...

, Ian Stewart, Dick Taylor and Tony Chapman had played together for the group Blues Incorporated

Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated, or simply Blues Incorporated, were an English blues band formed in London in 1961, led by Alexis Korner and including at various times Jack Bruce, Charlie Watts, Terry Cox, Davy Graham, Ginger Baker, Art ...

before creating a new name inspired by the Muddy Waters

McKinley Morganfield (April 4, 1913 April 30, 1983), known professionally as Muddy Waters, was an American blues singer and musician who was an important figure in the post- war blues scene, and is often cited as the "father of modern Chicag ...

1950 single " Rollin' Stone". The day before the concert, an ad in the July 11, 1962, edition of ''Jazz News'', a London weekly jazz paper, had shown the drummer to be Mick Avory

Michael Charles Avory (born 15 February 1944) is an English musician, best known as the longtime drummer and percussionist for the English rock band the Kinks. He joined them shortly after their formation in 1964 and remained with them until 1984, ...

, who later played for The Kinks

The Kinks were an English rock band formed in Muswell Hill, north London, in 1963 by brothers Ray and Dave Davies. They are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s. The band emerged during the height of British rhyt ...

, rather than Chapman. Avory himself, however, would say in an interview that he did not play in the event.

* The first telephone signals carried by satellite were made by engineers between Goonhilly

Goonhilly Satellite Earth Station is a large radiocommunication site located on Goonhilly Downs near Helston on the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall, England. Owned by Goonhilly Earth Station Ltd under a 999-year lease from BT Group plc, it was ...

in the U.K. and Andover, Maine

Andover is a town in Oxford County, Maine, United States. The population was 752 at the 2020 census. Set among mountains and crossed by the Appalachian Trail, Andover is home to the Lovejoy Covered Bridge and was the site of the Andover Earth ...

, in the U.S.

*Representatives of Gemini Project Office (GPO), Flight Operations Division, Air Force Space System Division, Marshall Space Flight Center, and Lockheed attended an Atlas-Agena

The Atlas-Agena was an American expendable launch system derived from the SM-65 Atlas missile. It was a member of the Atlas family of rockets, and was launched 109 times between 1960 and 1978. It was used to launch the first five Mariner uncrew ...

coordination meeting in Houston. GPO presented a list of minimum basic maneuvers of the Agena to be commanded from both the Gemini spacecraft and ground command stations. GPO also distributed a statement of preliminary Atlas-Agena basic mission objectives and requirements. A total of 10 months would be required to complete construction and electrical equipment checkout to modify pad 14 for the Atlas-Agena, beginning immediately after the last Project Mercury

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

flight.

*A technical team at Air Force Missile Test Center

The Space Launch Delta 45 (SLD 45) is a unit of the United States Space Force. The Space Launch Delta 45 is assigned to Space Systems Command and headquartered at Patrick Space Force Base, Florida. The wing also controls Cape Canaveral Space Fo ...

, Cape Canaveral, Florida - responsible for detailed launch planning, consistency of arrangements with objectives, and coordination - met for the first time with official status and a new name. The group of representatives from all organizations supplying major support to the Gemini-Titan launch operations, formerly called the Gemini Operations Support Committee, was now called the Gemini-Titan Launch Operations Committee.

* Born: Julio César Chávez

Julio César Chávez González (; born July 12, 1962), also known as Julio César Chávez Sr., is a Mexican former professional boxer who competed from 1980 to 2005. A multiple-time world champion in three weight divisions, Chávez was list ...

, Mexican boxer, WBC champion at three levels (super featherweight, lightweight, light welterweight and welterweight) between 1984 and 1996; in Ciudad Obregón

Ciudad Obregón is a city in southern Sonora. It is the state's second largest city after Hermosillo and serves as the municipal seat of Cajeme, as of 2020, the city has a population of 436,484. Ciudad Obregón is south of the state's northe ...

* Died: James T. Blair, Jr., 60, Governor of Missouri 1957–1961, died along with his wife, of accidental carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning typically occurs from breathing in carbon monoxide (CO) at excessive levels. Symptoms are often described as " flu-like" and commonly include headache, dizziness, weakness, vomiting, chest pain, and confusion. Large ...

at his home, near Jefferson City, Missouri.

July 13

Events Pre-1600

* 1174 – William I of Scotland, a key rebel in the Revolt of 1173–74, is captured at Alnwick by forces loyal to Henry II of England.

* 1249 – Coronation of Alexander III as King of Scots.

*1260 – The Livon ...

, 1962 (Friday)

* Burmese leader Ne Win

Ne Win ( my, နေဝင်း ; 10 July 1910, or 14 or 24 May 1911 – 5 December 2002) was a Burmese politician and military commander who served as Prime Minister of Burma from 1958 to 1960 and 1962 to 1974, and also President of Burma ...

left the country for a trip to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, "for a medical check up".

* With his popularity declining, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

fired seven senior members of his cabinet, including Chancellor of the Exchequer Selwyn Lloyd

John Selwyn Brooke Lloyd, Baron Selwyn-Lloyd, (28 July 1904 – 18 May 1978) was a British politician. Born and raised in Cheshire, he was an active Liberal as a young man in the 1920s. In the following decade, he practised as a barrister and ...

, the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, the Ministers of Defence and Education, and the Secretary of State for Scotland. The move was unprecedented in United Kingdom history, and was followed by the firing of nine junior ministers on Monday. Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe

John Jeremy Thorpe (29 April 1929 – 4 December 2014) was a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament for North Devon from 1959 to 1979, and as leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976. In May 1979 he was tried at the ...

would quip, "Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life." The British press would dub the event Macmillan's "Night of the Long Knives

The Night of the Long Knives (German: ), or the Röhm purge (German: ''Röhm-Putsch''), also called Operation Hummingbird (German: ''Unternehmen Kolibri''), was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from 30 June to 2 July 1934. Chancellor Ad ...

".

* Secretary-General of the United Nations

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-g ...

U Thant

Thant (; ; January 22, 1909 – November 25, 1974), known honorifically as U Thant (), was a Burmese diplomat and the third secretary-general of the United Nations from 1961 to 1971, the first non-Scandinavian to hold the position. He held t ...

arrived in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

, and paid tribute to Irish soldiers who fought in the Congo.

* AT&T

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile ...

President Eugene McNeely inaugurated international phone calling via satellite in a conversation with French Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

The Minister of Posts and Telegraphs, to which was later added the charge of Telephones (the position was later named "Minister of Posts and Telecommunications"), was, in the Government of France, the cabinet member in charge of the French Posta ...

Jacques Marette. On Telstar's next orbit, McNeely spoke with Sir Ronald German, the British General Post Office

The General Post Office (GPO) was the state postal system and telecommunications carrier of the United Kingdom until 1969. Before the Acts of Union 1707, it was the postal system of the Kingdom of England, established by Charles II in 1660. ...

Director-General.{{cite encyclopedia , url=http://claudelafleur.qc.ca/Spacecrafts-1962.html , title=Spacecrafts [sic] Launched in 1962 , encyclopedia=Spacecraft Encyclopedia , first=Claude , last=LeFleur

* Tests were conducted with a subject wearing a Mercury pressure suit in a modified Mercury spacecraft

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States, running from 1958 through 1963. An early highlight of the Space Race, its goal was to put a man into Earth orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Un ...

couch equipped with a B-70 (Valkyrie) harness. When this harness appeared to offer advantages over the existing Mercury harness, plans were made for further evaluation in spacecraft tests.

* To ensure mechanical and electrical compatibility between the Gemini spacecraft and the Gemini-Agena target vehicle, Gemini Project Office established an interface working group composed of representatives from Lockheed, McDonnell, Air Force Space Systems Division, Marshall, and Manned Spacecraft Center. The group's main function was to smooth the flow of data on design and physical details between the spacecraft and target vehicle contractors.

*Born: Tom Kenny

Thomas James Kenny (born July 13, 1962) is an American actor and comedian. He is known for voicing the titular character in ''SpongeBob SquarePants'' and associated media. Kenny has voiced many other characters, including Heffer Wolfe in '' ...

, American voice actor best-known as the voice of SpongeBob

''SpongeBob SquarePants'' (or simply ''SpongeBob'') is an American animated comedy television series created by marine science educator and animator Stephen Hillenburg for Nickelodeon. It chronicles the adventures of the title character ...

in over 250 episodes of the long-running cartoon ''SpongeBob SquarePants

''SpongeBob SquarePants'' (or simply ''SpongeBob'') is an American Animated series, animated Television comedy, comedy Television show, television series created by marine science educator and animator Stephen Hillenburg for Nickelodeon. It ...

''; in Syracuse, New York

Syracuse ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States. It is the fifth-most populous city in the state of New York following New York City, Buffalo, Yonkers, and Rochester.

At the 2020 census, the city' ...

July 14

Events Pre-1600

* 982 – King Otto II and his Frankish army are defeated by the Muslim army of al-Qasim at Cape Colonna, Southern Italy.

*1223 – Louis VIII becomes King of France upon the death of his father, Philip II.

*1420 ...

, 1962 (Saturday)

* A 1958 Pakistan law, banning all political parties, was repealed by a National Assembly resolution, amending the Constitution of 1962. The only requirement was that a party could not "prejudice Islamic ideology or the stability or integrity of Pakistan, and could not receive any aid from a foreign nation.

* In the third match of the rugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as just rugby league and sometimes football, footy, rugby or league, is a full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular field measuring 68 metres (75 yards) wide and 112 ...

Test series between Australia and Great Britain, held at Sydney Cricket Ground

The Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) is a sports stadium in Sydney, Australia. It is used for Test, One Day International and Twenty20 cricket, as well as, Australian rules football and occasionally for rugby league, rugby union and association f ...

, a controversial last-minute Australian try and the subsequent conversion resulted in an 18–17 win for Australia.

* Henry Brooke became the new UK Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all nationa ...

in Harold Macmillan's reshuffled cabinet.

* The Miss Universe 1962

Miss Universe 1962, the 11th Miss Universe pageant, was held on 14 July 1962 at the Miami Beach Auditorium in Miami Beach, Florida, United States. Norma Nolan of Argentina was crowned by her predecessor Marlene Schmidt of Germany.

The Best National ...

beauty pageant took place at Miami Beach, Florida

Miami Beach is a coastal resort city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. It was incorporated on March 26, 1915. The municipality is located on natural and man-made barrier islands between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay, the latter of which ...

, and was won by Norma Nolan

Norma Beatriz Nolan (born 22 April 1938) is an Argentine beauty queen who was the first woman from Argentina to win the Miss Universe title. Nolan is of Irish and Italian descent. She was crowned Miss Argentina in 1962 by her predecessor, Adria ...

of Argentina.

July 15

Events Pre-1600

*484 BC – Dedication of the Temple of Castor and Pollux in ancient Rome

* 70 – First Jewish–Roman War: Titus and his armies breach the walls of Jerusalem. ( 17th of Tammuz in the Hebrew calendar).

* 756 – ...

, 1962 (Sunday)

* The 1962 Tour de France

The 1962 Tour de France was the 49th edition of the Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The race consisted of 22 stages, including two split stages, starting in Nancy on 24 June and finishing at the Parc des Princes in Paris on 15 ...

concluded in Paris, with Jacques Anquetil

Jacques Anquetil (; 8 January 1934 – 18 November 1987) was a French road racing cyclist and the first cyclist to win the Tour de France five times, in 1957 and from 1961 to 1964.

He stated before the 1961 Tour that he would gain the ...

winning for the third time.

* ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' broke the story of thalidomide

Thalidomide, sold under the brand names Contergan and Thalomid among others, is a medication used to treat a number of cancers (including multiple myeloma), graft-versus-host disease, and a number of skin conditions including complications o ...

tablets that had been distributed in the United States, in a story by Morton Mintz under the headline "Heroine of FDA Keeps Bad Drug Off Market". As a result of the publicity, more than 2.5 million thalidomide pills, which had been distributed to physicians by the Richardson-Merrell pharmaceutical company pending approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, were recalled. Although thousands of babies were born with defects in Europe, the FDA identified only 17 known cases in the United States.

* Radiation killed all six animals, sent up 24 hours earlier by NASA, in the first test of whether astronauts could safely endure prolonged exposure to cosmic rays

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles or clusters of particles (primarily represented by protons or atomic nuclei) that move through space at nearly the speed of light. They originate from the Sun, from outside of the Solar System in our ...

. The two monkeys and four hamsters had been inside a space capsule that had been kept at an altitude of {{Convert, 131,000, ft by a balloon.

July 16, 1962 (Monday)

* French explorerMichel Siffre

Michel Siffre (born 3 January 1939) is a French underground explorer, adventurer and scientist. He was born in Nice, where he spent his childhood.

He received a postgraduate degree at the Sorbonne six months after completing his baccalauréat. ...

conducted a long-term experiment

A long-term experiment is an experimental procedure that runs through a long period of time, in order to test a hypothesis or observe a phenomenon that takes place at an extremely slow rate.

What duration is considered "long" depends on the acad ...

of chronobiology

Chronobiology is a field of biology that examines timing processes, including periodic (cyclic) phenomena in living organisms, such as their adaptation to solar- and lunar-related rhythms. These cycles are known as biological rhythms. Chronob ...

, the perception of the passage of time in the absence of information, staying underground in a cave for two months after entering. While inside, he used a one-way field telephone to signal to researchers when he was going to sleep, when he was getting up, and how much time had passed between events during his waking hours. He was brought back out on September 14, 1962, sixty days later; according to his diary, he thought only 35 days had passed and that the date was August 20.

July 17

Events Pre-1600

* 180 – Twelve inhabitants of Scillium (near Kasserine, modern-day Tunisia) in North Africa are executed for being Christians. This is the earliest record of Christianity in that part of the world.

*1048 – Damasu ...

, 1962 (Tuesday)

* Major Robert M. White

Robert Michael "Bob" White (July 6, 1924 – March 17, 2010) (Maj Gen, USAF) was an American electrical engineer, test pilot, fighter pilot, and astronaut. He was one of twelve pilots who flew the North American X-15, an experimental spaceplane ...

(USAF) piloted a North American X-15

The North American X-15 is a hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft. It was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. The X-15 set spee ...

to a record altitude of 314,750 feet (59 miles, 96 km), narrowly missing the 100 kilometer altitude Kármán line

The Kármán line (or von Kármán line ) is an attempt to define a boundary between Earth's atmosphere and outer space, and offers a specific definition set by the Fédération aéronautique internationale (FAI), an international record-keeping ...

that defines outer space

Outer space, commonly shortened to space, is the expanse that exists beyond Earth and its atmosphere and between celestial bodies. Outer space is not completely empty—it is a near-perfect vacuum containing a low density of particles, pred ...

, but passing the 50-mile altitude mark that NASA used to define the threshold of space. The record of {{Convert, 67, mi would be set by Joseph A. Walker on July 19, 1963.

* The "Small Boy" test shot Little Feller I became the final atmospheric nuclear test by the United States.

* The U.S. Senate voted 52–48 against further consideration of President Kennedy's proposed plan for Medicare, government-subsidized health care for persons drawing social security benefits. Two liberal U.S. Senators had switched sides, preventing a 50–50 tie that would have been broken in favor of Medicare by Vice-President Johnson; as President, Johnson would sign Medicare into law effective July 30, 1965.

* Four years after the USS ''Nautilus'' had become the first submarine to reach the geographic North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

, the Soviet Union reached the Pole with a sub for the first time, with the submarine K-3 (later renamed the '' Leninsky Komsomol'').

* The Eritrean Liberation Front

ar, جبهة التحرير الإريترية it, Fronte di Liberazione Eritreo

, war = the Ethiopian Civil War, Eritrean War of Independence and the Eritrean Civil Wars

, image =

, caption = Flag of the ELF ...

staged its first major attack in seeking to separate Eritrea from Ethiopia, by throwing a hand grenade at a reviewing stand that included General Abiy Abebe (Emperor Haile Selassie's representative), Eritrean provincial executive Asfaha Woldemikael, and Hamid Ferej, leader of the Eritrean provincial assembly.

July 18

Events Pre-1600

*477 BC – Battle of the Cremera as part of the Roman–Etruscan Wars. Veii ambushes and defeats the Roman army.

*387 BC – Roman-Gaulish Wars: Battle of the Allia: A Roman army is defeated by raiding Gauls, lead ...

, 1962 (Wednesday)

* Typhoon Kate formed a short distance from northern Luzon.

* Unpopular and unable to implement economic reforms, Ali Amini

Ali Amini ( fa, علی امینی; 12 September 1905–12 December 1992) was an Iranian politician who was the Prime Minister of Iran from 1961 to 1962. He held several cabinet portfolios during the 1950s, and served as a member of parliamen ...

resigned as Prime Minister of Iran

The Prime Minister of Iran was a political post that had existed in Iran (Persia) during much of the 20th century. It began in 1906 during the Qajar dynasty and into the start of the Pahlavi dynasty in 1923 and into the 1979 Iranian Revolution ...

. He would be replaced by Asadollah Alam

Asadollah Alam ( fa, اسدالله علم; 24 July 1919 – 14 April 1978) was an Iranian politician who was prime minister during the Shah's regime from 1962 to 1964. He was also minister of Royal Court, president of Pahlavi University and ...

.

* The largest space vehicle, up to that time, began orbiting the Earth, after the United States launched the communications satellite "Big Shot". After going aloft, the silvery balloon was inflated to its full size as a sphere with a diameter of {{Convert, 135, ft.

* After Peruvian Army officers used a Sherman tank to batter down the gates of the presidential palace in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of the central coastal part of ...

, they arrested Manuel Prado Ugarteche

Manuel Carlos Prado y Ugarteche (April 21, 1889 – August 15, 1967) was a banker who served twice as President of Peru. Son of former president Mariano Ignacio Prado, he was born in Lima and served as the nation's 43rd (1939 - 1945) and 46th (1 ...

, the 73-year-old President of Peru

The president of Peru ( es, link=no, presidente del Perú), officially called the president of the Republic of Peru ( es, link=no, presidente de la República del Perú), is the head of state and head of government of Peru. The president is th ...

, and replaced him with a junta led by General Ricardo Pérez Godoy. The election results of June 10

Events Pre-1600

* 671 – Emperor Tenji of Japan introduces a water clock ( clepsydra) called ''Rokoku''. The instrument, which measures time and indicates hours, is placed in the capital of Ōtsu.

*1190 – Third Crusade: Frederick I ...

were annulled.

* The Minnesota Twins

The Minnesota Twins are an American professional baseball team based in Minneapolis. The Twins compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central Division. The team is named after the Twin Cities area w ...

became the first Major League Baseball team to hit two grand slams in the same inning of a game, as Bob Allison

William Robert Allison (July 11, 1934 – April 9, 1995) was an American professional baseball outfielder who played for the Washington Senators / Minnesota Twins of Major League Baseball from to .

Allison attended the University of Kansas for ...

and Harmon Killebrew

Harmon Clayton Killebrew Jr. (; June 29, 1936May 17, 2011), nicknamed "The Killer" and "Hammerin' Harmon", was an American professional baseball first baseman, third baseman, and left fielder. He was a prolific power hitter who spent most of hi ...

drove in eight runs in the first inning of a 14–3 win over the Cleveland Indians

The Cleveland Guardians are an American professional baseball team based in Cleveland. The Guardians compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) American League Central, Central division. Since , they have ...

. In 50 years, the feat has been accomplished seven more times since then, most recently on September 11, 2015, in the eighth inning of a 14 to 8 win by the Baltimore Orioles over the Kansas City Royals. On April 23, 1999, both of the St. Louis Cardinals' grand slams in the third inning were made by the same batter, Fernando Tatis

Fernando is a Spanish and Portuguese given name and a surname common in Spain, Portugal, Italy, France, Switzerland, former Spanish or Portuguese colonies in Latin America, Africa, the Philippines, India, and Sri Lanka. It is equivalent to the G ...

.

* Born: Abu Sabaya

Abu Sabaya ( ; July 18, 1962 – June 21, 2002), born Aldam Tilao, was one of the leaders of the Abu Sayyaf in the southern Philippines until he was killed by soldiers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines in 2002.

Life

Abu Sabaya was a former e ...

, Philippine leader of rebel group Abu Sayyaf

Abu Sayyaf (; ar, جماعة أبو سياف; ', ASG), officially known by the Islamic State as the Islamic State – East Asia Province, is a Jihadist militant and pirate group that follows the Wahhabi doctrine of Sunni Islam. It is base ...

; as Aldam Tilao in Isabela, Basilan

Isabela, officially the City of Isabela (Chavacano: ''Ciudad de Isabela''; Tausūg: ''Dāira sin Isabela''; Yakan: ''Suidad Isabelahin''; fil, Lungsod ng Isabela), is a 4th class component city and '' de facto'' capital of the province of Bas ...

(killed 2002)

* Died:

**Volkmar Andreae

Volkmar Andreae (5 July 1879 – 18 June 1962) was a Swiss conductor and composer.

Life and career

Andreae was born in Bern. He received piano instruction as a child and his first lessons in composition with Karl Munzinger. From 1897 to 1900, ...

, 82, Swiss conductor and composer

**Eugene Houdry

Eugène Jules Houdry (Domont, France, April 18, 1892 – Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, July 18, 1962) was a mechanical engineer who graduated from École Nationale Supérieure d'Arts et Métiers in 1911.

Houdry served as a lieutenant in a tank com ...

, 70, French chemical engineer who developed high octane gasoline and the catalytic converter

A catalytic converter is an exhaust emission control device that converts toxic gases and pollutants in exhaust gas from an internal combustion engine into less-toxic pollutants by catalyzing a redox reaction. Catalytic converters are usual ...

July 19

Events Pre-1600

* AD 64 – The Great Fire of Rome causes widespread devastation and rages on for six days, destroying half of the city.

* 484 – Leontius, Roman usurper, is crowned Eastern emperor at Tarsus (modern Turkey). He is ...

, 1962 (Thursday)

* The first successful intercept of one missile by another took place at Kwajalein Island

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civilia ...

, with a Zeus missile passing within {{Convert, 2, km of an incoming Atlas missile, close enough for a nuclear warhead to disable an enemy weapon.

* Gemini Project Office and North American Aviation

North American Aviation (NAA) was a major American aerospace manufacturer that designed and built several notable aircraft and spacecraft. Its products included: the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the ...

agreed on guidelines for the design of the advanced paraglider trainer, the paraglider system to be used with static test article No. 2, and the paraglider system for the Gemini spacecraft. The most important of these guidelines was that redundancy would be provided for all critical operations.

* Born: Anthony Edwards, American film and television actor; in Santa Barbara, California

Santa Barbara ( es, Santa Bárbara, meaning " Saint Barbara") is a coastal city in Santa Barbara County, California, of which it is also the county seat. Situated on a south-facing section of coastline, the longest such section on the West ...

July 20

Events Pre-1600

* 70 – Siege of Jerusalem: Titus, son of emperor Vespasian, storms the Fortress of Antonia north of the Temple Mount. The Roman army is drawn into street fights with the Zealots.

* 792 – Kardam of Bulgaria defea ...

, 1962 (Friday)

* Government police arrested, tortured and killed Tou Samouth, Communist leader of the Khmer People's Revolutionary Party in Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand ...

. His successor, Saloth Sar, would go on to lead the Communist Party of Kampuchea

The Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK),, UNGEGN: , ALA-LC: ; french: Parti communiste du Kampuchea also known as the Khmer Communist Party,

as Pol Pot

Pol Pot; (born Saloth Sâr;; 19 May 1925 – 15 April 1998) was a Cambodian revolutionary, dictator, and politician who ruled Cambodia as Prime Minister of Democratic Kampuchea between 1976 and 1979. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist ...

, and then exact revenge on former government employees.

* France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

reestablished diplomatic relations

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

, a year after breaking ties following the Bizerte crisis

The Bizerte crisis (; ) occurred in July 1961 when Tunisia imposed a blockade on the French naval base at Bizerte, Tunisia, hoping to force its evacuation. The crisis culminated in a three-day battle between French and Tunisian forces that ...

.