Joseph Warren Revere (general) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

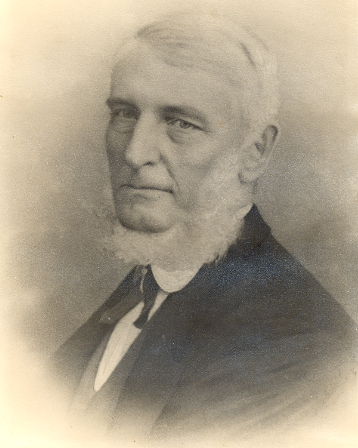

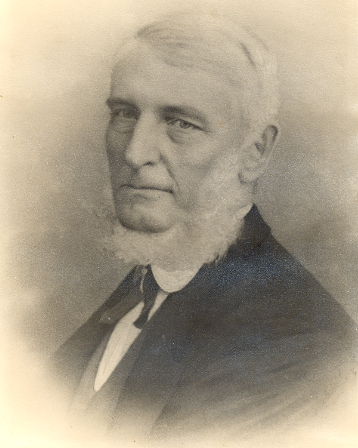

Joseph Warren Revere (May 17, 1812 – April 20, 1880) was a career

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

and Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

officer. He was the grandson of American revolutionary

Patriots, also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or American Whigs, were the colonists of the Thirteen Colonies who rejected British rule during the American Revolution, and declared the United States of America an independent n ...

figure Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

.

He was an amateur artist and autobiographer

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English per ...

, publishing two novels: ''A Tour of Duty in California'' (1849) and ''Keel and Saddle'' (1872)''.'' Both novels include memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

s of his experience traveling in the military. He was involved in the African Slave Trade Patrol

African Slave Trade Patrol was part of the Blockade of Africa suppressing the Atlantic slave trade between 1819 and the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Due to the abolitionist movement in the United States, a squadron of U.S. Navy ...

, the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans and Black Indians. It was part of a ser ...

, the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

, and the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

.

He was heavily involved in the 1845-1846 Conquest of California

The Conquest of California, also known as the Conquest of Alta California or the California Campaign, was an important military campaign of the Mexican–American War carried out by the United States in Alta California (modern-day California), t ...

, wherein American troops invaded Alta California

Alta California ('Upper California'), also known as ('New California') among other names, was a province of New Spain, formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but ...

. After the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

, he created a plantation in Rancho San Geronimo, enslaving Coast Miwok

Coast Miwok are an indigenous people that was the second-largest group of Miwok people. Coast Miwok inhabited the general area of modern Marin County and southern Sonoma County in Northern California, from the Golden Gate north to Duncans Poi ...

Natives. He later sold the property to his military friend Rodman Price.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Revere was a Union Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

who was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed after the 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

. Revere challenged the court-martial and published multiple pamphlets in attempts to clear his reputation. In 1862, during the Civil War, Revere converted to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

His 1854 Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

mansion is historically preserved for educational tours at Fosterfields

Fosterfields, also known as Fosterfields Living Historical Farm, is a farm and open-air museum at the junction of Mendham and Kahdena Roads in Morris Township, New Jersey. The oldest structure on the farm, the Ogden House, was built in 1774. Li ...

in Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Joseph Warren Revere was born in  In 1846, Revere patented Rancho San Geronimo, 8,701 acres of land seized during the

In 1846, Revere patented Rancho San Geronimo, 8,701 acres of land seized during the

"A brief history of potato farming in the #sangeronimovalley

, May 1 2020. However, two months later, the Army transferred Revere to San Diego, and Revere "is said to have left the property in the care of a Native-American resumably Coast Miwokforeman." Circa 1847, Revere continued to invade Mexican territory in the

While living on the Rancho in California, Revere befriended Irish immigrant Timothy "Old Tim" Murphy. Revere states, "I have often hunted eerwith Don Timoleo Murphy and his pack of

While living on the Rancho in California, Revere befriended Irish immigrant Timothy "Old Tim" Murphy. Revere states, "I have often hunted eerwith Don Timoleo Murphy and his pack of  Circa 1849, Revere's close friend Rodman Price visited Revere's Rancho San Geronimo plantation and was impressed. On December 28, 1849, Price paid Revere $7,500 to purchase half the land, with $2,500 up front. The two also agreed to split the profits of timber exports from the property.

Circa 1849, Revere's close friend Rodman Price visited Revere's Rancho San Geronimo plantation and was impressed. On December 28, 1849, Price paid Revere $7,500 to purchase half the land, with $2,500 up front. The two also agreed to split the profits of timber exports from the property.

Circa 1849, Revere temporarily received housing in

Circa 1849, Revere temporarily received housing in

In 1852, Revere retired to

In 1852, Revere retired to

1863. Revere, Joseph Warren. Published by C. A. Alvord. From Revere's perspective, he writes,

On May 30, 1865, Revere's pension was approved for $20 a month. Revere had applied as a wounded veteran. Around this time, he had difficulty walking due to his right leg injury at the 1862

On May 30, 1865, Revere's pension was approved for $20 a month. Revere had applied as a wounded veteran. Around this time, he had difficulty walking due to his right leg injury at the 1862

De Rivoire

ancestors. He made a drawing of the

In 1881, a year after Revere's death, tenant Charles Grant Foster purchased the entire Willows property. In the decades that followed, the farm was named

In 1881, a year after Revere's death, tenant Charles Grant Foster purchased the entire Willows property. In the decades that followed, the farm was named

General Joseph Warren Revere's ancestry

{{DEFAULTSORT:Revere, Joseph Warren 1812 births 1880 deaths American travel writers American male non-fiction writers American people of the Seminole Wars American people of the Bear Flag Revolt American Roman Catholics Mexican soldiers People of New Jersey in the American Civil War People from Morris Township, New Jersey Union Army generals United States Army officers Excelsior Brigade United States Navy officers United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy personnel of the Mexican–American War Recipients of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

on May 17, 1812 to Lydia LeBaron Goodwin and Dr. John Revere; he was a grandson of Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

. The Reveres descended from a French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Beza ...

family. He was named after General Joseph Warren, the famous doctor and general in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, who was a close friend of his grandfather.

In 1826, the fourteen-year-old Revere joined the United States Naval School in New York. Two years later, Revere joined the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

. His 25 years of tours of duty took him to Europe, the Pacific, and the Baltic States. He travelled to Singapore and met Czar Nicholas I

, house = Romanov-Holstein-Gottorp

, father = Paul I of Russia

, mother = Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Gatchina Palace, Gatchina, Russian Empire

, death_date =

...

of Russia. He was a polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Eu ...

, which aided him in his expeditions.

Some time in the 1830s, Revere fought to annex Florida during the Second Seminole War

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Native Americans and Black Indians. It was part of a ser ...

, on a mosquito fleet

The term Mosquito Fleet has had a variety of naval and commercial uses around the world.

United States

In U.S. naval and maritime history, the term has had ten main meanings:

#The United States Navy's fleet of small gunboats, leading up to and ...

near Florida's coast. He afterwards commanded an anti-piracy fleet in the West Indies. While in Spain, he encountered one of the Carlist Wars

The Carlist Wars () were a series of civil wars that took place in Spain during the 19th century. The contenders fought over claims to the throne, although some political differences also existed. Several times during the period from 1833 to 18 ...

.

Between 1835 and 1845, he was aboard the frigate USS Constitution

USS ''Constitution'', also known as ''Old Ironsides'', is a three-masted wooden-hulled heavy frigate of the United States Navy. She is the world's oldest ship still afloat. She was launched in 1797, one of six original frigates authorized ...

.

In 1837, he met Rosanna Duncan Lamb in Boston. They both had grandparents who were soldiers during the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. The courtship would be delayed due to Revere joining the United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

in 1838, the first American squadron to circumnavigate

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magel ...

the globe. He rejoined Lamb in 1840 for a brief time, before returning to the expedition. By 1841, Revere was promoted to lieutenant. In an unknown year, Revere reportedly saved the British HMS ''Ganges'' from shipwreck, for which Revere was "presented with a sword of honor by the governor-general of India."

On October 4 1842, Rosanna Duncan Lamb (April 16, 1818 - July 26, 1910) married Joseph Warren Revere in Boston. They had 5 children, although the first 3 died during childhood: John Revere (1844-1849), Frances Jane Revere (1849-1859), and Thomas Duncan Revere (1853-1856). The youngest two were lawyer Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to a ...

(1856-1901) and banker Augustus Lefebvre Revere

Augustus Lefebvre Revere was an American financier, banker, stock broker, and civic leader from Morristown, New Jersey. He was a member of the Morristown Club, the Morristown Golf Club, the Morristown Field Club, and the Washington Association o ...

(1861-1910), who both lived through adulthood.

In 1846, Revere was deeply involved in the American Conquest of California

The Conquest of California, also known as the Conquest of Alta California or the California Campaign, was an important military campaign of the Mexican–American War carried out by the United States in Alta California (modern-day California), t ...

, part of the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

. In June 1846, the Californios

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sinc ...

declared their independence from America, creating the California Republic

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now So ...

and raising Bear Flags across California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

.Walker p. 148 On the morning of July 9, 1846, Revere and 70 naval troops arrived at Yerba Buena, lowered the Bear Flag, and raised the American flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the ca ...

in its place - thereby claiming San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

as American territory. Later that day, Revere and troops repeated the flag replacement at Sonoma Plaza

Sonoma Plaza (Spanish: ''Plaza de Sonoma'') is the central plaza of Sonoma, California. The plaza, the largest in California, was laid out in 1835 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, founder of Sonoma.

Description

This plaza is surrounded by many h ...

in Sonoma, California. Revere's actions assisted American forces in bringing the California Republic

The California Republic ( es, La República de California), or Bear Flag Republic, was an unrecognized breakaway state from Mexico, that for 25 days in 1846 militarily controlled an area north of San Francisco, in and around what is now So ...

to an end after 25 days of independence.Walker p. 148

In 1846, Revere patented Rancho San Geronimo, 8,701 acres of land seized during the

In 1846, Revere patented Rancho San Geronimo, 8,701 acres of land seized during the Mexican-American war

Mexican Americans ( es, mexicano-estadounidenses, , or ) are Americans of full or partial Mexican heritage. In 2019, Mexican Americans comprised 11.3% of the US population and 61.5% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexica ...

. Revere created a plantation at Rancho San Geronimo, selling timber and farming potatoes. He enslaved Coast Miwok

Coast Miwok are an indigenous people that was the second-largest group of Miwok people. Coast Miwok inhabited the general area of modern Marin County and southern Sonoma County in Northern California, from the Golden Gate north to Duncans Poi ...

people, native to the Marin County area, to operate the plantation.San Geronimo Valley Historical Society"A brief history of potato farming in the #sangeronimovalley

, May 1 2020. However, two months later, the Army transferred Revere to San Diego, and Revere "is said to have left the property in the care of a Native-American resumably Coast Miwokforeman." Circa 1847, Revere continued to invade Mexican territory in the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. He was commended for his bravery in battle.

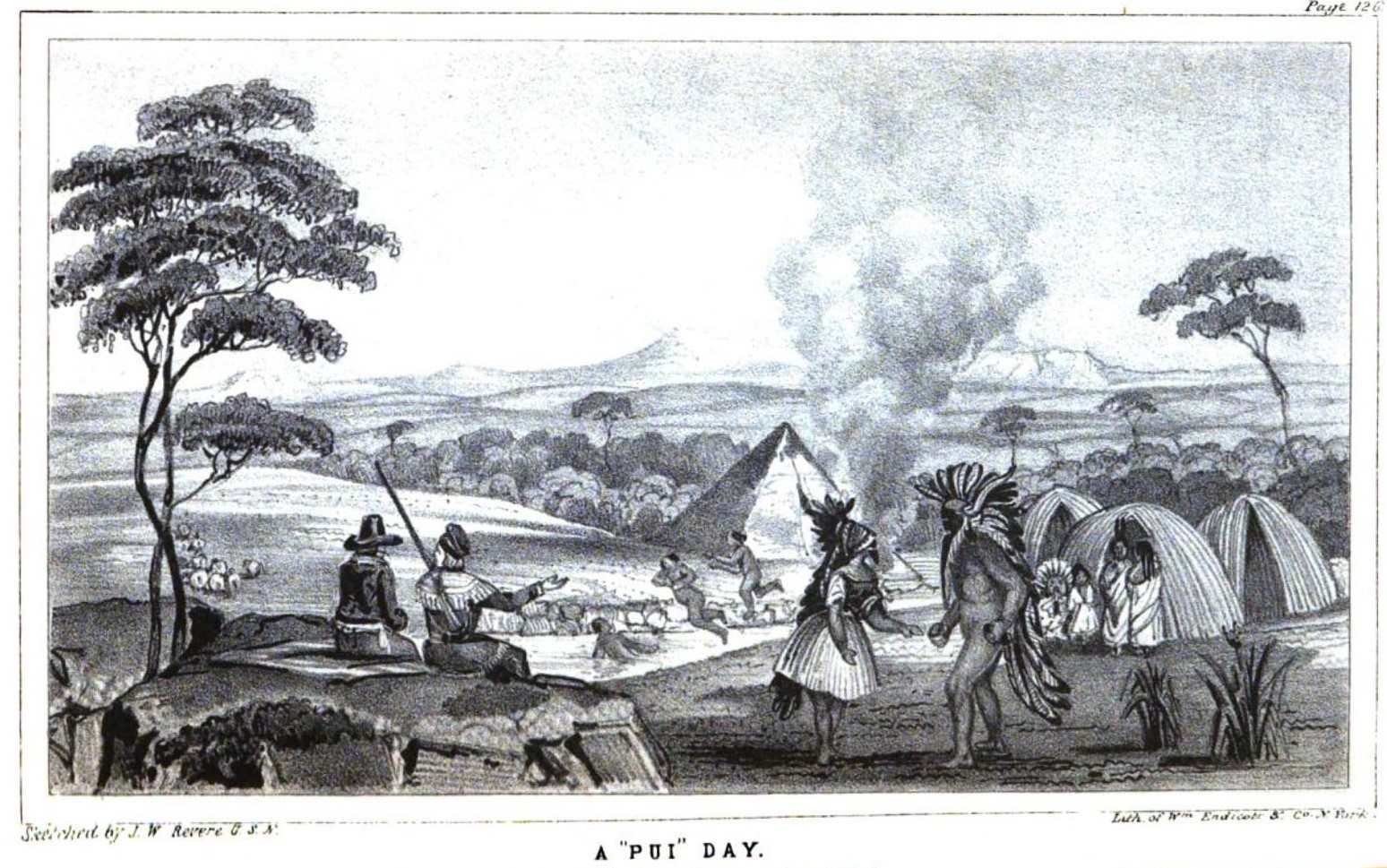

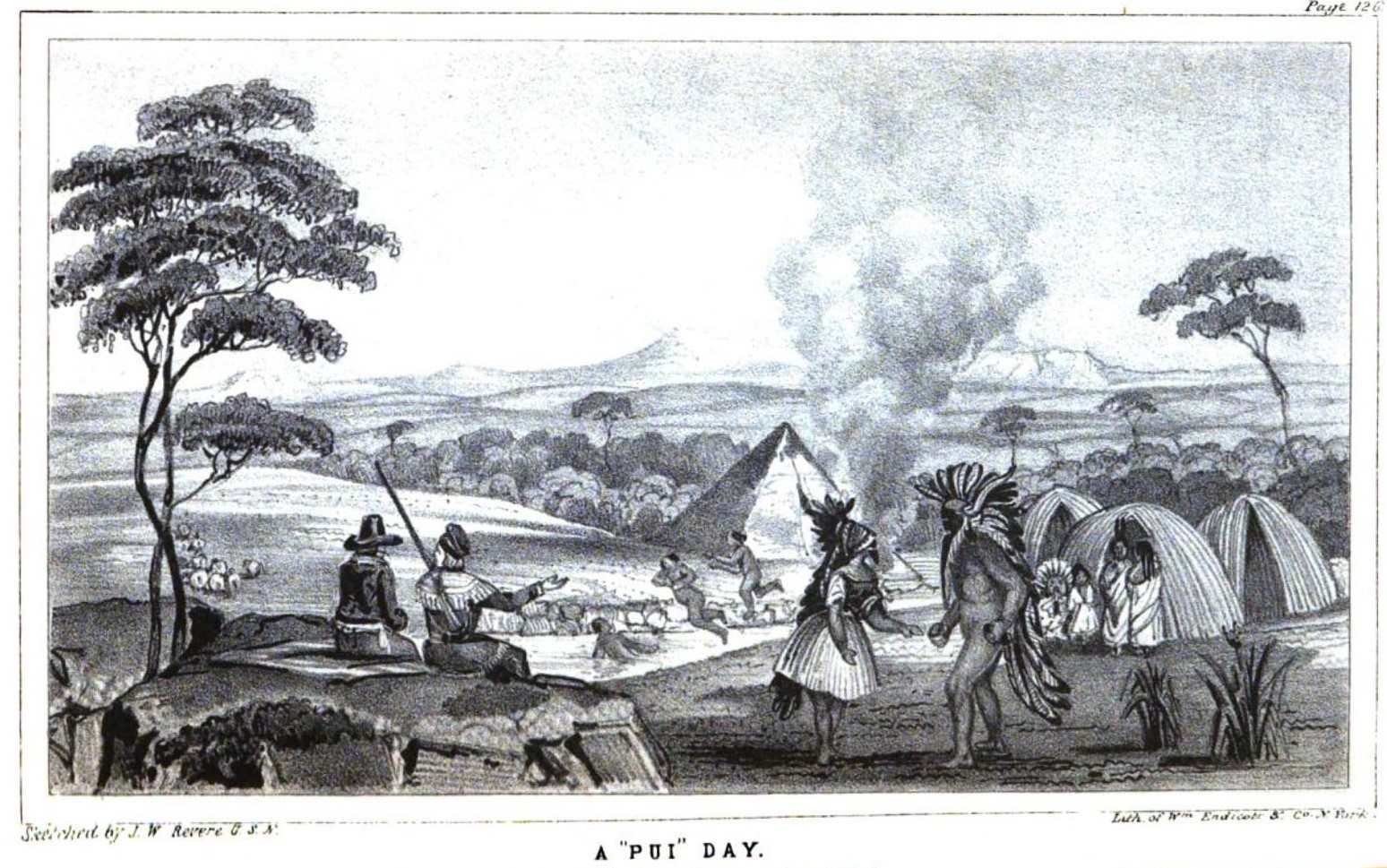

''A Tour of Duty in California''

In 1849, Roseanna Revere gave birth to Frances Jane Revere. The same year, Revere published his firstautobiographical

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

book, titled ''A Tour of Duty in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

: Including a Description of the Gold Region: and an Account of the Voyage Around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

; with Notices of Lower California, the Gulf

A gulf is a large inlet from the ocean into the landmass, typically with a narrower opening than a bay, but that is not observable in all geographic areas so named. The term gulf was traditionally used for large highly-indented navigable bodie ...

and Pacific Coasts, and the Principal Events Attending the Conquest of the Californias''. It was edited

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, photographic, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, org ...

by Joseph N. Balestier, a U.S. consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

of Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, who was his uncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an uncle is an aunt, and the reciprocal rela ...

by marriage, though Balestier refers to Revere as "my friend" in the foreword

A foreword is a (usually short) piece of writing, sometimes placed at the beginning of a book or other piece of literature. Typically written by someone other than the primary author of the work, it often tells of some interaction between the ...

. The book includes illustrations and lithographs by Revere as well as his original submission for the Great Seal of California

The Great Seal of the State of California was adopted at the California state Constitutional Convention of 1849 and has undergone minor design changes since then, the last being the standardization of the seal in 1937. The seal shows Athena i ...

. Revere dedicated the book to John Y. Mason

John Young Mason (April 18, 1799October 3, 1859) was a United States representative from Virginia, the 16th and 18th United States Secretary of the Navy, the 18th Attorney General of the United States, United States Minister to France and a Uni ...

, secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

1844–1849, stating " isable and upright discharge of his public duties has won for him the respect and applause of his countrymen." The memoir was advertised in the ''Boston Evening Transcript

The ''Boston Evening Transcript'' was a daily afternoon newspaper in Boston, Massachusetts, published from July 24, 1830, to April 30, 1941.

Beginnings

''The Transcript'' was founded in 1830 by Henry Dutton and James Wentworth of the firm of D ...

'', the ''Charleston Courier'', the ''Baltimore Sun'', ''The Living Age'', ''The United States Democratic Review'', and the ''Richmond Enquirer''. The ''Boston Evening Transcript

The ''Boston Evening Transcript'' was a daily afternoon newspaper in Boston, Massachusetts, published from July 24, 1830, to April 30, 1941.

Beginnings

''The Transcript'' was founded in 1830 by Henry Dutton and James Wentworth of the firm of D ...

'' heralded the novel for vividly describing California as "the new land of promise."

While living on the Rancho in California, Revere befriended Irish immigrant Timothy "Old Tim" Murphy. Revere states, "I have often hunted eerwith Don Timoleo Murphy and his pack of

While living on the Rancho in California, Revere befriended Irish immigrant Timothy "Old Tim" Murphy. Revere states, "I have often hunted eerwith Don Timoleo Murphy and his pack of rey Rey may refer to:

*Rey (given name), a given name

*Rey (surname), a surname

* Rey (''Star Wars''), a character in the ''Star Wars'' films

*Rey, Iran, a city in Iran

* Ray County, in Tehran Province of Iran

* ''Rey'' (film), a 2015 Indian film

*The ...

ounds, and a more gallant sport cannot be found in the wide world." Although he lived alongside Californios

Californio (plural Californios) is a term used to designate a Hispanic Californian, especially those descended from Spanish and Mexican settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries. California's Spanish-speaking community has resided there sinc ...

and Native tribes of California, Revere scorned their customs, referring to them as "the most wretched of mankind" and often using the term " savage." After attending a Pui Day (Feast Day), Revere states,Like most savages, he Indians of Californiareason with a rude but true philosophy, that the loss of a life so hard and precarious as theirs is little to be regretted...To give themIn ''A Tour of Duty,'' Revere also demonstrates his support ofcivil rights Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ..., on an equality with the whites, would be more absurd than to grant such rights to children under ten years of age...When it is remembered, thatsmall-pox Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) cer ...is not the only desolating disease which follows in the wake of the white man, and that his rum has proved among our Indians as fatal as his natural disorders, it is very clear, that unless measures be promptly taken to protect and preserve the inoffensive natives of California, the present generation will live to read the epitaph of the whole race.

Manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special virtues of the American people and th ...

: he states that the " Anglo-Saxon race...seems destined to possess the whole of the North American Continent." This possibly displays Revere's notions of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

. Revere did not support African slavery in California, though this was not due to abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

reasons; it was due to a preference to enslave people of other races, including Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/ racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of O ...

s and Native Californians. He states:The great expense and risk of transporting slaves to a country so remote, the vast number of Indians whose labor is so much cheaper than slave-labor can possibly be, the utter absence among the Spanish Californians of all prejudice with respect to color, the fact that the Indians are better herdsmen (The above statement is exemplified by his enslavement ofvaquero The ''vaquero'' (; pt, vaqueiro, , ) is a horse-mounted livestock herder of a tradition that has its roots in the Iberian Peninsula and extensively developed in Mexico from a methodology brought to Latin America from Spain. The vaquero became t ...s), than any African can ever become, and the ease with which any number ofKanakas Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Queensland (Australia) in the 19 ...from theSandwich Islands The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Ku ..., andCoolie A coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a term for a low-wage labourer, typically of South Asian or East Asian descent. The word ''coolie'' was first popularized in the 16th century by European traders acros ...s, and other laborers from Asia can be procured, render it an absurdity that negro slavery will ever be established in California.

Coast Miwok

Coast Miwok are an indigenous people that was the second-largest group of Miwok people. Coast Miwok inhabited the general area of modern Marin County and southern Sonoma County in Northern California, from the Golden Gate north to Duncans Poi ...

people to operate his San Geronimo plantation in the 1840s. Circa 1849, Revere's close friend Rodman Price visited Revere's Rancho San Geronimo plantation and was impressed. On December 28, 1849, Price paid Revere $7,500 to purchase half the land, with $2,500 up front. The two also agreed to split the profits of timber exports from the property.

Circa 1849, Revere's close friend Rodman Price visited Revere's Rancho San Geronimo plantation and was impressed. On December 28, 1849, Price paid Revere $7,500 to purchase half the land, with $2,500 up front. The two also agreed to split the profits of timber exports from the property.

Possible affair

Circa 1849, Revere temporarily received housing in

Circa 1849, Revere temporarily received housing in San Rafael, California

San Rafael ( ; Spanish for " St. Raphael", ) is a city and the county seat of Marin County, California, United States. The city is located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's popula ...

(although he had his own Rancho at this point). The landlord was British geologist and artist James Gay Sawkins

James Gay Sawkins (1806–July 20, 1878) was an artist, geologist, copper miner, and illustrator. He was a member of the Geological Society of London who joined and led research during England's West Indian Geological Surveys of the islands of Tr ...

, then the husband of Octavia "Rosa" Sawkins, a British teacher raised in the West Indies.

Witnesses described seeing Sawkins and Revere sitting together on a hammock, frequently meeting in Sawkins's room, and visiting the house of Chapita Miranda together (described during the court proceeding as "a house of ill fame," "an improper place").

On November 26, 1849, James Sawkins entered his home and greeted Revere with a handshake, noticing he was "trembling and cold." Sawkins testified:Entering my wife's room, she was sitting in a rocking chair with her head inclined down. Putting my hand on her table I asked her what was the matter. That she received with an expression of countenance I never saw her before. "James, I am no longer your wife; don't come near me; don't touch me; hate me, for I hate you. I will never live with you again."James said he ran to a nearby Mr. Murphy and asked what had happened. He claimed Mr. Murphy led him to the veranda and said, "Chloroform or some damnable drug has been given to your poor wife." When James found that the

laudanum

Laudanum is a tincture of opium containing approximately 10% powdered opium by weight (the equivalent of 1% morphine). Laudanum is prepared by dissolving extracts from the opium poppy (''Papaver somniferum Linnaeus'') in alcohol (ethanol).

R ...

bottle in the medicine cabinet was empty, he asked his wife what became of it and she said she drank it, i.e. attempted suicide

A suicide attempt is an attempt to die by suicide that results in survival. It may be referred to as a "failed" or "unsuccessful" suicide attempt, though these terms are discouraged by mental health professionals for implying that a suicide resu ...

. James Sawkins "became alarmed for her mind," because he recalled her mother had also had some type of psychosis

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavi ...

.

The next morning, Rosa did not allow James to force her into her room, leading to a physical altercation in which both fell to the ground. Rosa left the home. James and Revere set out via horseback to find her, but did not succeed. They searched again at dawn.

Three days later, James led a search party into the woods, where a carman

In Celtic mythology, Carman or Carmun was a warrior and sorceress from Athens who tried to invade Ireland in the days of the Tuatha Dé Danann, along with her three sons, Dub ("black"), Dother ("evil") and Dian ("violence"). She used her magica ...

informed James that Rosa had escaped to Pacheco, California

Pacheco is a census-designated place (CDP) in Contra Costa County, California. The population was 3,685 at the 2010 census. It is bounded by Martinez to the north and west, respectively; it is bounded by Concord to the east, and Pleasant Hi ...

. James brought Rosa back to the house and promised to get her a lawyer so that a divorce could be filed.

The following day, James began to suspect that Rosa Sawkins and Revere had had an affair. Rosa asked James not to injure Revere, blaming herself for her actions and mental health.

A Naval Board of Inquiry comprised of officer James Glynn

James Glynn (1800–1871) was a U.S. Navy officer who in 1848 distinguished himself by being the first American to negotiate successfully with the Japanese during the " Closed Country" period.

James Glynn entered the United States Navy on March ...

, officer Charles W. Pickering, and judge William E. Levy convened on the USS ''Warren'' to "inquire into the truth of the serious allegations" against Revere. He was charged with "having deprived Mr. James G. Sawkins of his wife," Rosa Sawkins.

James Sawkins claimed that Rosa Sawkins said,I gave myself up to Revere, what passed I scarcely know, but remorse was too great to bear. I flew to the Laudinum bottle and emptied it at one draught in the hopes of killing myself. Oh, that I had died, but now I love him; yes, James, to the bottom of my soul and I will live for him alone.The court case was complicated by the discovery that James G. Sawkins had another wife whom he married at the age of 18 while she was 35, and the couple had two daughters. Rosa Sawkins was denied work as a teacher as a result of the case. On May 20, 1850, Revere wrote a letter to the

U.S. Department of the Navy

The United States Department of the Navy (DoN) is one of the three military departments within the Department of Defense of the United States of America. It was established by an Act of Congress on 30 April 1798, at the urging of Secretary of ...

objecting the allegations made by the court of inquiry. The navy replied that Revere's objections were "well founded."

On July 1st 1850, Revere wrote his letter of resignation from the navy after almost twenty years of service. This may have been to prevent himself from being officially Court-martialed

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

, which would ensure that his wife learned about the incident. He did not describe the affair and subsequent proceedings in 1872 biographical novel ''Keel and Saddle,'' claiming instead that he resigned due to lack of promotion opportunities. He later was court-martialed during the Civil War for different reasons.

Later career

On August 6 1851, Price bought the remainder of Revere's property for $8,000. The same year, Revere formed a coastal trading business with Sandy McGregor, for which they purchased ''La Golondrina'', a ship built in Spain that could hold a crew of 25. Revere and McGregor presumably headed the crew. Revere joined theMexican Army

The Mexican Army ( es, Ejército Mexicano) is the combined land and air branch and is the largest part of the Mexican Armed Forces; it is also known as the National Defense Army.

The Army is under the authority of the Secretariat of National ...

with the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

. He was ordered to reorganize the Mexican Artillery Corps and was honored by the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

and Mexican Government

The Federal government of Mexico (alternately known as the Government of the Republic or ' or ') is the national government of the United Mexican States, the central government established by its constitution to share sovereignty over the republ ...

s.

In 1851, ''La Golondrina'' encountered a beached Spanish ship off the coast of Mexico, which was under siege by Native Mexicans. Revere and McGregor fought and possibly murdered the Mexican attackers allowing the Spanish "crew of seventeen men and one woman" to escape. For this deed, Queen Isabella II

Isabella II ( es, Isabel II; 10 October 1830 – 9 April 1904), was Queen of Spain from 29 September 1833 until 30 September 1868.

Shortly before her birth, the King Ferdinand VII of Spain issued a Pragmatic Sanction to ensure the successio ...

knighted Revere in the Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Order of Isabella the Catholic ( es, Orden de Isabel la Católica) is a Spanish civil order and honor granted to persons and institutions in recognition of extraordinary services to the homeland or the promotion of international relations a ...

in 1851.Los Angeles County Museum Museum Patrons' Association's ''Quarterly'' p. 7 (1961). Soon afterward, Revere and McGregor dissolved their partnership and sold the vessel "to a group of Englishmen hoping to find gold in Australia."

He visited Mexico City to meet with Mariano Arista

José Mariano Arista (26 July 1802 – 7 August 1855) was a Mexican soldier and politician.

He was in command of the Mexican forces at the opening battles of the Mexican American War: the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la P ...

, the president of Second Federal Republic of Mexico

)

, common_languages = Spanish (official), Nahuatl, Yucatec Maya, Mixtecan languages, Zapotec languages

, religion = Roman Catholicism ( official religion until 1857)

, currency = Mexican real ...

from 1851 to 1853. Arista offered Revere "a commission as Lieutenant Colonel of Artillery in the Mexican Army." Revere accepted and reorganized the artillery and trained officers. However, after multiple revolts, Arista resigned and was exiled from the country, prompting Revere to quit the position and move to Morristown, New Jersey.

First retirement

In 1852, Revere retired to

In 1852, Revere retired to Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters t ...

Ashbel Bruen of Chatham to construct a unique mansion on the hill, which Revere helped design. His customized mansion, titled The Willows, was designed in the Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

style (specifically, Carpenter Gothic

Carpenter Gothic, also sometimes called Carpenter's Gothic or Rural Gothic, is a North American architectural style-designation for an application of Gothic Revival architectural detailing and picturesque massing applied to wooden structures ...

). With Revere and Bruen likely based their design on the 1849 Olmstead House, designed by British architect Gervase Wheeler

Gervase Wheeler (1815–1889) was a British architect, writer, and illustrator who designed homes in the United States.

Wheeler is best known for publishing influential architectural pattern books ''Rural Homes'' (1851) and ''Homes for the Peo ...

, the pattern of which appeared in the book ''Rural Homes of 1851.''

Construction was complete in 1854, when Revere moved in. In the dining room, Revere likely painted the elaborate trompe-l'œil

''Trompe-l'œil'' ( , ; ) is an artistic term for the highly realistic optical illusion of three-dimensional space and objects on a two-dimensional surface. ''Trompe l'oeil'', which is most often associated with painting, tricks the viewer into ...

murals of still lives, the Revere family crest, and a bouquet of baguette

A baguette (; ) is a long, thin type of bread of French origin that is commonly made from basic lean dough (the dough, though not the shape, is defined by French law). It is distinguishable by its length and crisp crust.

A baguette has a dia ...

s. Above his family crest, he painted Thomas Ken

Thomas Ken (July 1637 – 19 March 1711) was an English cleric who was considered the most eminent of the English non-juring bishops, and one of the fathers of modern English hymnody.

Early life

Ken was born in 1637 at Little Berkhampstead, ...

's 1674 doxology, "Praise God from whom all blessings flow

A doxology ( Ancient Greek: ''doxologia'', from , '' doxa'' 'glory' and -, -''logia'' 'saying') is a short hymn of praises to God in various forms of Christian worship, often added to the end of canticles, psalms, and hymns. The tradition der ...

," often sung to the tune of the Old 100th.

The home was historically preserved by Caroline Foster, who bequeathed it to the Morris County Park System in 1979. It is now part of the Fosterfields Living Historical Farm

Fosterfields, also known as Fosterfields Living Historical Farm, is a farm and open-air museum at the junction of Mendham and Kahdena Roads in Morris Township, New Jersey. The oldest structure on the farm, the Ogden House, was built in 1774. List ...

, where guests can attend tours of the home.

The years 1857 and 1858 found Revere touring Europe where he claimed to have served as "a military consultant for numerous governments." with his friend, Union army general Phil Kearny. Revere also went to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

, where the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

awarded him the Indian Mutiny Medal

__NOTOC__

The Indian Mutiny Medal was a campaign medal approved in August 1858, for officers and men of British and Indian units who served in operations in suppression of the Indian Mutiny.

The medal was initially sanctioned for award to troops ...

for helping suppress the Indian Rebellion

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major uprising in India in 1857–58 against Company rule in India, the rule of the East India Company, British East India Company, which functioned as a sovereign power on behalf of the The Crown, British ...

of 1857–58.

On September 25 1859, Frances Jane Revere died at the age of 10 of pneumonia. The family was "grief stricken" and travelled to Europe in November, coming back the following year. Possibly during this time, Revere was present at the Battle of Sulferino during the Second Italian War of Independence

The Second Italian War of Independence, also called the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Sardinian War or Italian War of 1859 ( it, Seconda guerra d'indipendenza italiana; french: Campagne d'Italie), was fought by the Second French Empire and t ...

.DeRose,Mary 1996,'' Joseph Warren Revere:His Civil War Years'' in ''The Farm and Mill Gazette'' of The Morris County Park Commission.

Civil War service

In 1852, while on a steamboat in Mississippi, Revere discussedastrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

with Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, who was a deep believer of the subject. Though Revere was skeptical, he provided Jackson "the necessary data for calculating a horoscope

A horoscope (or other commonly used names for the horoscope in English include natal chart, astrological chart, astro-chart, celestial map, sky-map, star-chart, cosmogram, vitasphere, radical chart, radix, chart wheel or simply chart) is an as ...

; and in the course of a few months, ereceived from him a letter, which epreserved, enclosing a scheme of evere'snativity." Jackson predicted a "culmination of the malign aspect" in the first days of May 1863. This would align with the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 3, 1863, the battle that led to Revere's court-martial.

Revere returned to the US in 1860. When the Civil War began in 1861, Revere tried to join the Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

but was informed that there were no officer slots available for him. Having been appointed as head of the New Jersey Militia during the governorship of Rodman Price, Revere decided to enlist in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

.

In 1861, Revere accepted a commission as Colonel of the 7th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry The 7th New Jersey Infantry Regiment was an American Civil War infantry regiment from New Jersey that served a three-year enlistment in the Union Army. It was mustered into federal service on September 3, 1861. The regiment trained at Camp Olden in ...

. He led it into the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battle

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comma ...

.

In August 1862, Revere fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

. The Union Army commended him for his bravery, but "the brutality he encountered left Revere badly shaken." During this battle, he received a wound that severely damaged his right leg, leading to difficulty walking.

In October 1862, Joseph Revere was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

of U.S. Volunteers

United States Volunteers also known as U.S. Volunteers, U.S. Volunteer Army, or other variations of these, were military volunteers called upon during wartime to assist the United States Army but who were separate from both the Regular Army and the ...

.

During the Peninsula campaign, Revere's regiment suffered many deaths, and he contracted rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection. Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful ...

. Afterwards, Revere went to Washington DC while Union troops regrouped. While there, he entered an unspecified Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

church and felt "the impulse, or rather inspiration, to become a Catholic."

On October 19, 1862, Revere was baptized at the Baltimore Basilica

The Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, also called the Baltimore Basilica, was the first Roman Catholic cathedral built in the United States, and was among the first major religious buildings construc ...

in Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

by Reverend H. B. Coskery. This was followed by Revere's first Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

on October 26 of that year. Years later, Archbishop Bayley (possibly James Roosevelt Bayley

James Roosevelt Bayley (August 23, 1814 – October 3, 1877) was an American prelate of the Catholic Church. He served as the first Bishop of Newark (1853–1872) and the eighth Archbishop of Baltimore (1872–1877).

Early life and educa ...

) confirmed Revere in Morristown's Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary parish. He created a painting for the parish: the "Espousals of the Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph," which as of 2012 continues to be on display in Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church.

In December 1862, in the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Bur ...

, he led a brigade but saw little action. He was later named to command the Excelsior Brigade.

Court-martial

Revere's most personally challenging moment of his Civil War career came after theBattle of Chancellorsville

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War (1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because h ...

when blame was being assigned for the Union Army's loss. Revere was court-martialed due to an event occurring on May 3, 1863.

A letter circa 1863 summarizes the incident:Brigadier General Revere was convicted byOn the morning of May 3, 1863, nearCourt-martial A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...and dismissed, for marching his command, without orders from his superior officer, to about three miles from the scene of action and towards the United States Ford; but by direction of the President this dismissal was revoked, and General Revere's resignation was accepted.

Falmouth, Virginia

Falmouth is a census-designated place (CDP) in Stafford County, Virginia, United States. Situated on the north bank of the Rappahannock River at the falls, the community is north of and opposite the city of Fredericksburg. Recognized by the U. ...

, division commander Maj. Gen. Hiram Berry was mortally wounded after charging the Confederate line. Next in seniority was General Mott, who was severely wounded; therefore, Revere assumed command of the group. As the battle lacked a clear front line

A front line (alternatively front-line or frontline) in military terminology is the position(s) closest to the area of conflict of an armed force's personnel and equipment, usually referring to land forces. When a front (an intentional or unin ...

, Revere commanded his troops (the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

) to reform at a point set by compass. This three-mile march, described by Revere as a "regrouping effort" and not a retreat, led to his being court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed as ordered by General Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

.

Revere claims he was censured for "cowardice on the field," a claim which makes him smile due to its "flagrant vindictiveness."A STATEMENT of the case of Brigadier-General Joseph W. Revere, United States Volunteers: tried by court-martial, and dismissed from the service of the United States, August 10th, 1863. With a Map, a copy of the record of the Trial, and an appendix1863. Revere, Joseph Warren. Published by C. A. Alvord. From Revere's perspective, he writes,

I heard...of the death of General Berry, my division commander, who was killed at about half-past seven o'clock; and immediately afterwards I met Brigadier-General Mott, the next in seniority in the division, going to the rear, severely wounded. I at once concluded that I was the commanding officer of the Second Division, Third Corps... The need of some action was urgent. I believed myself to be the division commander...My men were worn with the marches and battles of four days, with want of rest and food for the last twenty-four hours, and with sharp fighting for the last four, and were nearly out of ammunition...I assensible of the responsibility involved, but confident that it was the only course for bringing my troops speedily into efficient service... To sum up all in a few words,—after the fight was ended, left without orders, and crowded off the field, I led away a handful of worn and disorganized men towards a point where, in my belief, an action might even then be going on, and brought them back within six hours, after retiring less than three miles, two thousand strong, refreshed and resupplied. Was this a breach of duty?On August 10, 1863, Revere was tried by

court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

and dismissed.

Pamphlets

In September 1863, while living in The Willows, Revere wrote a 48-page pamphlet admonishing his court-martial and defending his reputation. It was titled "A Statement of the case of Brigadier-General Joseph W. Revere, United States Volunteers: tried by court-martial, and dismissed from the service of the United States, August 10th, 1863." It included "a Map, a copy of the record of the Trial, and an appendix." The pamphlet had a marbled cover and was addressed to the public hoping they will "acquit him of the censure cast upon him by the court." Revere included footnotes fromStephen Vincent Benét

Stephen Vincent Benét (; July 22, 1898 – March 13, 1943) was an American poet, short story writer, and novelist. He is best known for his book-length narrative poem of the American Civil War, '' John Brown's Body'' (1928), for which he receiv ...

's 1862 "A Treatise on Military Law and the Practise of Courts-Martials." Letters from different personnel about the situation are collected in the appendix. It was published by electrotyper and printer C. A. Alvord on 15 Vandewater Street in Farmingdale, New York

Farmingdale is an incorporated village on Long Island within the Town of Oyster Bay in Nassau County, New York. The population was 8,189 as of the 2010 Census.

The Lenox Hills neighborhood is adjacent to Bethpage State Park and the rest of the ...

.

In "A Statement," Revere insinuates that the court-martial does not consider his decades of prior experience:I have been for thirty years a sailor and a soldier. Had I been a politician in epaulettes, plying in the camp the arts of the caucus...there might be retributive, though indirect, justice in this sentence. But I have been more versed in war than in intrigue. On all that Court, eminent as most of its members were, there was not one who was not my junior in length of employment in the United States service...At least, with such a record, I had a right to expect from the Court, even with my unheard, greater lenity than is shown in this cruel sentence...In 1863, General J. Egbert Farnum defended Revere's reputation in a letter, concluding with, " r the careless and inconsiderate slanders that have been circulated n New York City newspapers affecting you as a brave man, and an honorable soldier, I am with you responsible." 7 others signed the letter endorsing Farnum's testament. In 1864, J. H. Eastburn's Press in Boston published Revere's second pamphlet titled "A Review of the case of Brigadier-Gen. Joseph W. Revere, U.S. Volunteers, tried by court-martial and dismissed from the service of the United States, August 10, 1863." The pamphlet is written in third-person and does not specify its author, but it is nevertheless credited to Revere. In the pamphlet's conclusion, the author uses

Socratic questioning

Socratic questioning (or Socratic maieutics) was named after Socrates. He used an educational method that focused on discovering answers by asking questions from his students. According to Plato, who was one of his students, Socrates believed t ...

to imply that Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

made larger mistakes than Revere without repercussions, and the last line invokes a quote from Act II Scene II of Shakespeare's 1604 play, ''Measure for Measure

''Measure for Measure'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1603 or 1604 and first performed in 1604, according to available records. It was published in the '' First Folio'' of 1623.

The play's plot features its ...

'':Why should charges be preferred against Revere for " neglect of duty, &c.," in leaving on the field the arms of the killed and wounded, and wasting ammunition fired at the enemy by his command, and why should Hooker get off unscathed, after having, the very next day, ingloriously abandoned the same field, in presence of an inferior force of rebels, in opposition to all his generals in , except the of these proceedings, leaving not only arms, equipments, and ammunition, but immense stores of all kinds forIn 1864, Revere's supporters submitted letters and petitions to Lincoln, urging him to undo the dishonorable court-martial. These included Nehemiah Perry, George Middleton, andLee Lee may refer to: Name Given name * Lee (given name), a given name in English Surname * Chinese surnames romanized as Li or Lee: ** Li (surname 李) or Lee (Hanzi ), a common Chinese surname ** Li (surname 利) or Lee (Hanzi ), a Chinese ...'s especial delectation, and his wounded to the care of the rebel surgeons? Is the typical sword of military justice two edged and cutting both ways, or does say truly - "That in the officer's but a word, / Which in the soldier is rank heresy." ?

William G. Steele

William Gaston Steele (December 17, 1820, Somerville, New Jersey – April 22, 1892, Somerville, New Jersey) was an American Democratic Party politician who represented New Jersey's 3rd congressional district from 1861 to 1865.

Steele was ...

; they sent a petition on January 29, 1864 stating they felt "the judgement of the court martial in the case of Brig. Gen. Revere, has been rendered upon a mistaken state of facts and that the service of the government would be greatly advanced by his reinstatement into the service."

In January 1865, he wrote a pamphlet titled "Sequel to the Statement," presumably a sequel to his 1863 pamphlet.

President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

overturned the court's ruling and reinstated Revere but accepted Revere's resignation at the same time. As a lifelong member of the Democratic Party, that was probably the best deal Revere could expect from a Republican administration. In response to this situation, Revere was voted the honor of the rank of Brevet Major General by the United States Congress in 1866.

Postbellum career and death

On May 30, 1865, Revere's pension was approved for $20 a month. Revere had applied as a wounded veteran. Around this time, he had difficulty walking due to his right leg injury at the 1862

On May 30, 1865, Revere's pension was approved for $20 a month. Revere had applied as a wounded veteran. Around this time, he had difficulty walking due to his right leg injury at the 1862 Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

.

On August 3, 1866, surgeon Dr. Lewis Fisher examined Revere, who stated he was "totally incapacitated for obtaining his subsistence by manual labor." This raised Revere's pension to $30.

After his resignation, Revere began traveling the globe and continued writing autobiographies, but his health had been affected by his Civil War service. He had suffered from a severe case of rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection. Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful ...

during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign and had been severely wounded at the 1862 Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

.

On April 18, 1868, while farming at The Willows, Revere published a horse breeding advertisement in ''The'' ''Jerseyman'':''Blood Will Tell.'' The thoroughbred Stallion Jupiter will stand this season at my place, for a limited number of mares. Jupiter is one of the best strain of blood in America, being got by the celebrated Jupiter out of Golden Fleece. A beautiful chestnut, 12 1/2 hands high, the fastest four mile horse in the State; and of great endurance and bottom, in perfect health. In order to afford the Farmers of Morris County an opportunity to refresh their stock, terms will be low; viz., $25 to insure and $12 cash for a single occassion. J. W. Revere, Mendham Road near Morristown.In 1872, Revere's second book was published; the

autobiographical

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English peri ...

''Keel and Saddle: A Retrospect of 40 years of Military and Naval Service''. It was published by James R. Osgood & Co. The chapters detail his military-related travels and acquaintances in countries including (chronologically) Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. The book is dedicated "to the memories" of Colonel Paul Joseph Revere and assistant surgeon Edward H. R. Revere, both of whom died in battle.

In 1872's ''Keel and Saddle'', after detailing his experience freeing a ship of enslaved people'','' Revere wrote, "None of us could understand a word the slaves uttered: indeed, they appeared hardly to possess the organ of speech, so deeply guttural and barbarous was their uncouth dialect, - more like the chattering of baboons than any human jargon...In my opinion, extensive colonization is the only practical mode of benefiting 'benighted Africa.'"

On January 9, 1873, a secretary to President Grant wrote the following letter to Revere concerning his book:Sir: The President directs me to acknowledge the receipt of and to express to you his thanks for the copy of "Keel and Saddle" you were kind enough to send him. I am, Sir, Your humble svt., nintelligibleSecretaryLetter from the Executive Mansion. "FOSTERFIELDS ARCHIVES\Revere Archives\Revere Box 1\Letter January 9, 1873." January 9th, 1873 – via Fosterfields Collections, Morris County Park Commission.In 1875, while touring near Vienne in southeast France, by chance he visited the ruined chateau of hi

De Rivoire

ancestors. He made a drawing of the

coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

, Argent three fesses Gules, overall on a bend Azure three fleur-de-lis

The fleur-de-lis, also spelled fleur-de-lys (plural ''fleurs-de-lis'' or ''fleurs-de-lys''), is a lily (in French, and mean 'flower' and 'lily' respectively) that is used as a decorative design or symbol.

The fleur-de-lis has been used in the ...

Or, from which he derived his differenced arms, displayed on his grave marker as Argent 'two' fesses Gules, overall on a bend Azure three flour-de-lis 'palewise' Or.

Health decline and death

Circa the 1870s, a posthumous biography claims Revere's health was "completely shattered by wounds and diseases incurred in service and his existence became one of unbroken suffering." From 1871 to 1880, the Reveres rented out their Morristown mansion to multiple tenants. This is likely when Revere purchased the historic 1807Sansay House

The Sansay House is a residential dwelling in Morristown, New Jersey. It was built in 1807. In the early 19th century, it was the site of a French dancing school led by Monsieur Louis Sansay. On July 14, 1825, Louis Sansay held a ball in Lafayette ...

, possibly to live closer to the center of Morristown. Tenants of his Willows estate included Charles Grant Foster (father of Caroline Foster) and author Bret Harte

Bret Harte (; born Francis Brett Hart; August 25, 1836 – May 5, 1902) was an American short story writer and poet best remembered for short fiction featuring miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold Rush.

In a caree ...

.

On April 15, 1880, Revere experienced "neuralgia

Neuralgia (Greek ''neuron'', "nerve" + ''algos'', "pain") is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Classification

Under the general heading of neural ...

of the heart" while on a ferry

A ferry is a ship, watercraft or amphibious vehicle used to carry passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo, across a body of water. A passenger ferry with many stops, such as in Venice, Italy, is sometimes called a water bus or water ta ...

to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

(possibly a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

or cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest is when the heart suddenly and unexpectedly stops beating. It is a medical emergency that, without immediate medical intervention, will result in sudden cardiac death within minutes. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and possi ...

) as well as rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including ar ...

. Friends placed him in Buck's HotelThe 1902 source states the hotel as "Buch's Hotel." No record was found of a Buch's Hotel in Hoboken, but a "Buck's Hotel" in Hoboken did exist at 68-70 York Street, Hoboken according to http://www.cityofjerseycity.org/docs/grundy.shtml, so it can be assumed that the author made a spelling error. in Hoboken

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,69 ...

. He died five days later, on April 20, 1880, at 67 years of age. His funeral was private but "largely attended by his many friends."

His name appears, but lined through, in the June 1, 1880 U.S. Federal Census for his family in the City of Morristown, Morris County, New Jersey. Revere and his immediate family are buried at Holy Rood Cemetery in Morristown, several miles away from The Willows.

Legacy

In 1881, a year after Revere's death, tenant Charles Grant Foster purchased the entire Willows property. In the decades that followed, the farm was named

In 1881, a year after Revere's death, tenant Charles Grant Foster purchased the entire Willows property. In the decades that followed, the farm was named Fosterfields

Fosterfields, also known as Fosterfields Living Historical Farm, is a farm and open-air museum at the junction of Mendham and Kahdena Roads in Morris Township, New Jersey. The oldest structure on the farm, the Ogden House, was built in 1774. Li ...

, and Foster converted it into a dairy farm breeding Jersey cattle

The Jersey is a British list of cattle breeds, breed of small dairy cattle from Jersey, in the British Channel Islands. It is one of three Channel Island cattle breeds, the others being the Alderney (cattle), Alderney – now extinct – and th ...

. The Fosters kept the Revere mansion largely intact. Meanwhile, the Revere family likely continued to live in Morristown's Sansay House

The Sansay House is a residential dwelling in Morristown, New Jersey. It was built in 1807. In the early 19th century, it was the site of a French dancing school led by Monsieur Louis Sansay. On July 14, 1825, Louis Sansay held a ball in Lafayette ...

.

In 1888, Joseph Sabin

Joseph Sabin (9 December 1821—5 June 1881) was a Braunston, England-born bibliographer and bookseller in Oxford, Philadelphia, and New York City. He compiled the "stupendous" multivolume ''Bibliotheca Americana: A Dictionary of Books Relating to ...