Joseph Priestley and education on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Priestley

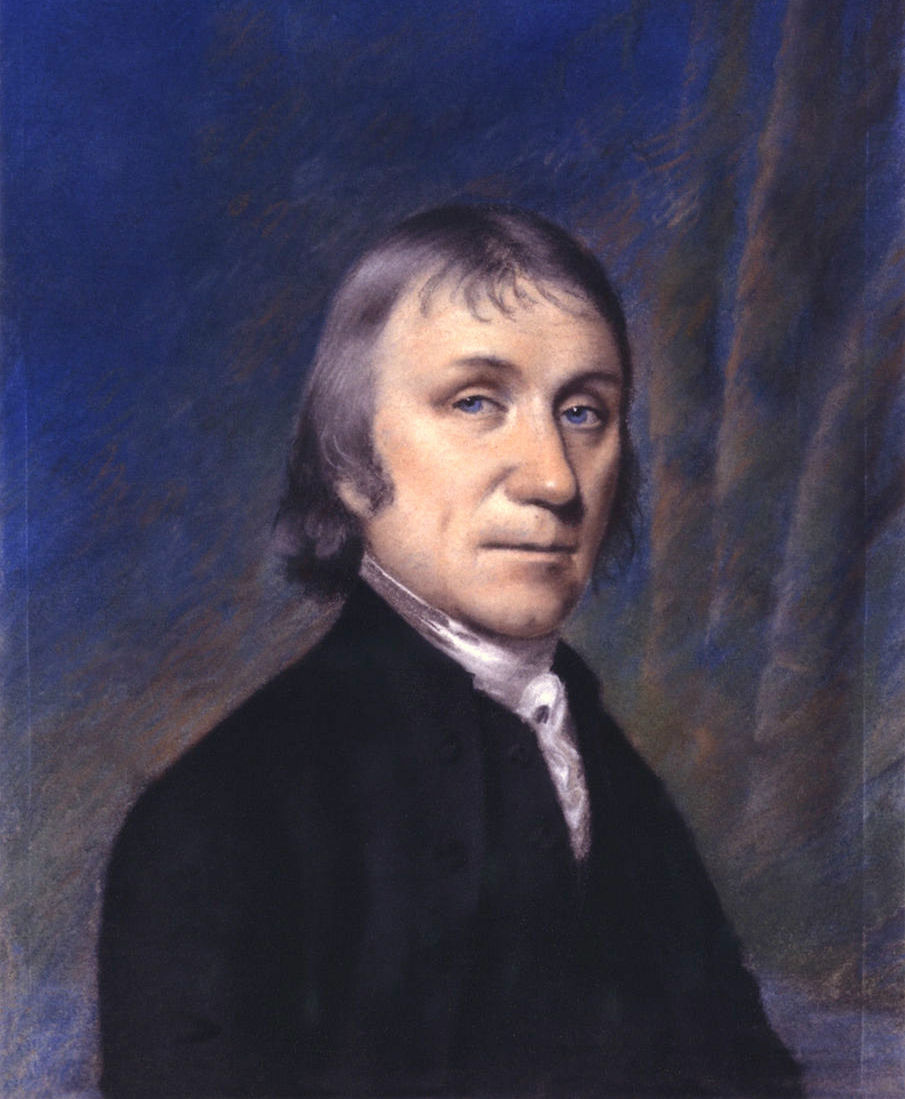

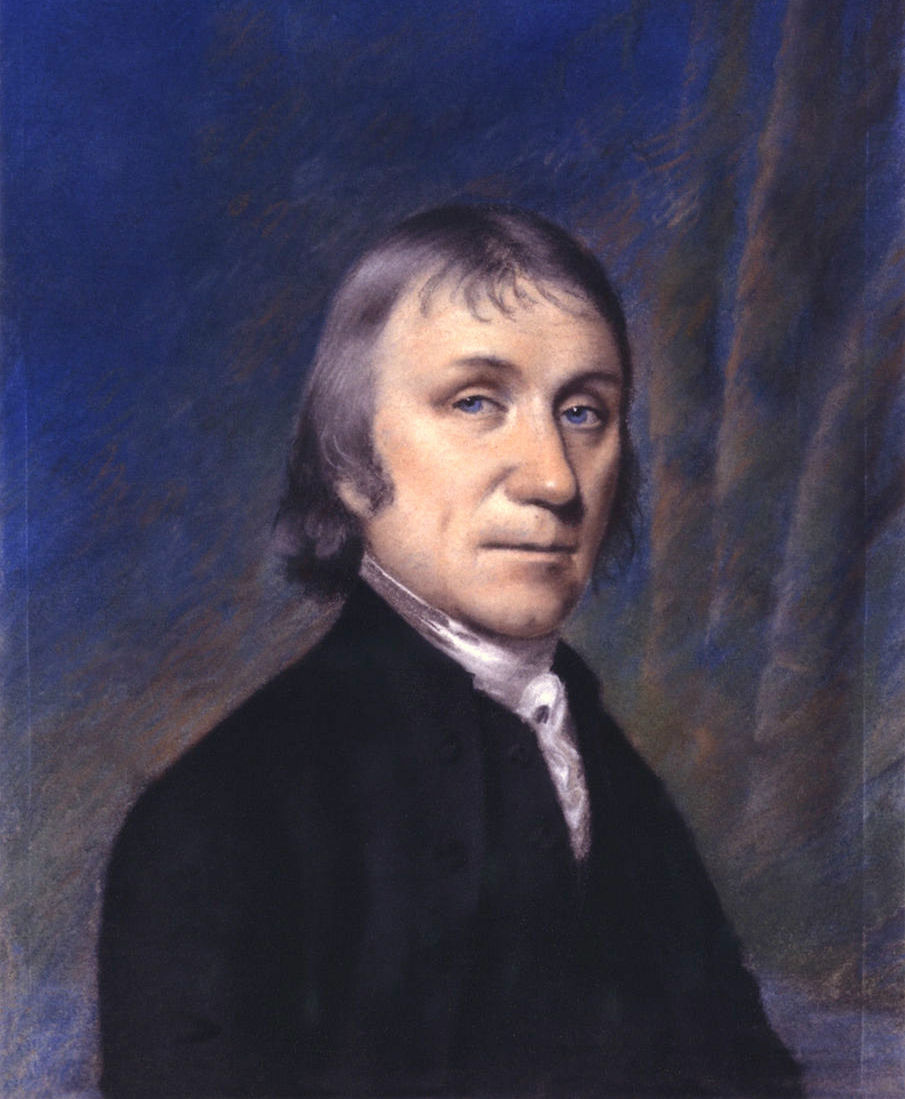

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted exp ...

( – 8 February 1804) was a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

, Dissenting

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

clergyman

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be Academia, academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized b ...

, and theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

. While his achievements in all of these areas are renowned, he was also dedicated to improving education in Britain; he did this on an individual level and through his support of the Dissenting academies

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

. His grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes domain ...

textbook was innovative and highly influential. More importantly, though, Priestley introduced a liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin "free" and "art or principled practice") is the traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term '' art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically th ...

curriculum at Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then ...

, arguing that a practical education would be more useful to students than a classical one. He was also the first to advocate the study and teaching of modern history, an interest driven by his belief that humanity was improving and could bring about Christ's Millennium.

Personal and institutional teaching

Priestley was a teacher in one way or another throughout his entire adult life. Once he discovered how much he enjoyed teaching, he consistently returned to this calling. At the school he established inNantwich

Nantwich ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East in Cheshire, England. It has among the highest concentrations of listed buildings in England, with notably good examples of Tudor and Georgian architecture. ...

, Cheshire, he taught a wide range of topics to the town's children: Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

(and perhaps Greek), geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

, mathematics, and English grammar

English grammar is the set of structural rules of the English language. This includes the structure of words, phrases, clauses, Sentence (linguistics), sentences, and whole texts.

This article describes a generalized, present-day Standard English ...

. Unusually for the time, he also taught natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

. Following the success of this school, he was offered the position of tutor of modern languages and rhetoric at Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then ...

. In later years, when he lived in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

and Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

, he created classes for the youth of his parishes; in Birmingham his three classes totaled 150 students and he helped organize the New Meeting Sunday schools for the poor.

Having received an excellent education at Daventry, a Dissenting academy

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

, and convinced that education was the key to shaping people and the world's future, Priestley continued to support the Dissenting academies throughout his life. For example, he advised the founders of New College at Hackney on its curriculum and preached a charity sermon on the "proper Objects of Education" to help raise money for the school. After emigrating to America in 1794, Priestley continued the educational projects that had always been important to him. He attempted to find funding for the Northumberland Academy and donated his library to it, but the academy did not open until 1813 and closed soon after. He communicated with Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

regarding the proper organization of a university and when Jefferson founded the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with highly selective ad ...

, it was Priestley's curricular principles that dominated the school. Jefferson also passed Priestley's advice on to Bishop James Madison, whose College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William I ...

also followed Priestley's maxims.

Wherever Priestley went, he also instructed people in natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

. In Nantwich, he bought scientific instruments, such as a microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

, for the school, and encouraged his students to give public presentations of their experiments. In Calne

Calne () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, southwestern England,OS Explorer Map 156, Chippenham and Bradford-on-Avon Scale: 1:25 000.Publisher: Ordnance Survey A2 edition (2007). at the northwestern extremity of the North Wessex Downs ...

, where he was a tutor to the son of Lord Shelburne

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, (2 May 17377 May 1805; known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history), was an Irish-born British Whig statesman who was the first ...

, Priestley convinced his patron to buy expensive equipment with which to teach his son the fundamentals of natural philosophy. He wrote in his ''Miscellaneous Observations relating to Education

{{Short pages monitor

As a supplement to his lectures on history, Priestley also designed and published '' A Chart of Biography'' (1765) and a ''New Chart of History'' (1769) (which he dedicated to

As a supplement to his lectures on history, Priestley also designed and published '' A Chart of Biography'' (1765) and a ''New Chart of History'' (1769) (which he dedicated to

Priestley pondered what form the best religious education would take throughout his life. In the 1760s, when he was a student at

Priestley pondered what form the best religious education would take throughout his life. In the 1760s, when he was a student at

The Joseph Priestley Society

- Comprehensive site which includes a bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism

(full text from google books)

Lectures on General History, and General Policy

(full text from google books)

Heads of Lectures on Course of Experimental Philosophy

(full text from google books)

A Description of a New Chart of History

(full text from google books)

Letters to Dr. Horne, Dean of Canterbury, to the Young Men who are in a Course of Education for the Christian Ministry at the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge

(full text from google books) {{DEFAULTSORT:Joseph Priestley And Education English grammar History education Religion and education History of education in England

Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model us ...

, Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ni ...

, Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

.

The theory underpinning Priestley's millennial

Millennials, also known as Generation Y or Gen Y, are the Western demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000s ...

view of history and his educational philosophy, was David Hartley's theory of association. Hartley's associationism

Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believed ...

, an expansion of John Locke's theories in ''Essay Concerning Human Understanding

''An Essay Concerning Human Understanding'' is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 (although dated 1690) with the printed title ''An Essay Concerning Humane Understand ...

'' (1690) and laid out in '' Observations on Man'' (1749), postulated that the human mind operated according to natural laws and that the most important law for the formation of the self was "associationism." For Hartley, associationism was a physical process: vibrations in the physical world traveled through the nerves attached to people's sense organs and ended up in their brains. The brain connected the vibrations of whatever sensory input it was receiving with whatever feelings or ideas that the brain was simultaneously "thinking." These "associations" were impossible to avoid, formed as they were simply by experiencing the world; they were also the foundation of a person's character. Locke famously warns against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the darkness, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other." Associationism provided the scientific basis for Priestley's belief that man is "perfectible" and served as the foundation for all of his pedagogical innovations.

Because Priestley viewed education as one of the primary forces shaping a person's character as well as the basis of morality, he, unusually for his time, promoted the education of women. Alluding to the language of Locke's ''Essay Concerning Human Understanding'', he wrote: "certainly, the minds of women are capable of the same improvement, and the same furniture, as those of men." He argued that if women were to care for children and be intellectually stimulating companions for their husbands, they had to be well-educated. Although Priestley advocated education for middle-class women, he did not extend this logic to the poor.

Charts of biography and history

As a supplement to his lectures on history, Priestley also designed and published '' A Chart of Biography'' (1765) and a ''New Chart of History'' (1769) (which he dedicated to

As a supplement to his lectures on history, Priestley also designed and published '' A Chart of Biography'' (1765) and a ''New Chart of History'' (1769) (which he dedicated to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

). These charts and their accompanying ''Descriptions'' would allow students, Priestley said, to "trace out distinctly the dependence of events to distribute them into such periods and divisions as shall lay the whole claim of past transactions in a just and orderly manner."

The ''Chart of Biography'' covers a vast timespan, from 1200 BC to 1800 AD, and includes two thousand names. Priestley organized his list into six categories: Statesman and Warriors; Divines and Metaphysicians; Mathematicians and Physicians (natural philosophers were placed here); Poets and Artists; Orators and Critics (prose fiction authors were placed here); and Historians and Antiquarians (lawyers were placed here). Priestley's "principle of selection" was fame, not merit; therefore, as he mentions, the chart is a reflection of current opinion. He also wanted to ensure that his readers would recognize the entries on the chart. Priestley had difficulty assigning his all of his people to individual categories; he attempted to list them in the category under which their most important work had been done. Machiavelli is therefore listed as a historian rather than a statesman and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

is listed as a statesman instead of an orator. The chart was also arranged in order of importance; "statesmen are placed on the lower margin, where they are easier to see, because they are the names most familiar to readers."

The ''Chart of History'' lists events in 106 separate locations; it illustrates Priestley's belief that the entire world's history was significant, a relatively new development in the eighteenth century, which had begun with Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

and William Robertson. The world's history is divided up into the following geographical categories: Scandinavia, Poland, Russia, Great Britain, Spain, France, Italy, Turkey in Europe, Turkey in Asia, Germany, Persia, India, China, Africa and America. Priestley aimed to show the history of empires and the passing of power; the subtitle of the ''Description'' that accompanied the chart was "A View of the Principle Revolutions of Empire that have taken place in the World" and he wrote that:

The capital use f the ''Charts'' was asa most excellent mechanical help to the knowledge of history, impressing the imagination indelibly with a just image of the rise, progress, extent, duration, and contemporary state of all the considerable empires that have ever existed in the world.As Arthur Sheps in his article about the ''Charts'' explains, "the horizontal line conveys an idea of the duration of fame, influence, power and domination. A vertical reading conveys an impression of the contemporaneity of ideas, events and people. The number or density of entries . . . tells us about the vitality of any age." Voids in the chart indicated intellectual Dark Ages, for example. Both ''Charts'' were popular for decades—the ''

A New Chart of History

In 1769, 18th-century British polymath Joseph Priestley published ''A New Chart of History'' and its prose explanation as a supplement to his ''Lectures on History and General Policy''. Together with his '' Chart of Biography'' (1765), which he d ...

'' went through fifteen editions by 1816. The trustees of Warrington were so impressed with Priestley's lectures and charts that they arranged for the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

to grant him a Doctor of Law degree in 1764.

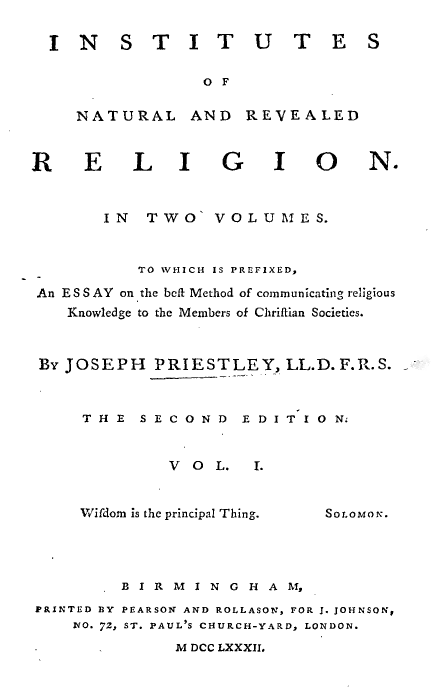

Religious education

Priestley pondered what form the best religious education would take throughout his life. In the 1760s, when he was a student at

Priestley pondered what form the best religious education would take throughout his life. In the 1760s, when he was a student at Daventry Academy

Daventry Academy was a dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by English Dissenters. It moved to many locations, but was most associated with Daventry, where its most famous pupil was Joseph Priestley. It had a high reputation, a ...

, he imbibed the pedagogical principles of its founder, Philip Doddridge

Philip Doddridge D.D. (26 June 1702 – 26 October 1751) was an English Nonconformist (specifically, Congregationalist) minister, educator, and hymnwriter.

Early life

Philip Doddridge was born in London the last of the twenty children of ...

; although he was dead, Doddridge's emphasis on academic rigor and freedom of thought lived on at the school and impressed Priestley. These ideals would always be a part of Priestley's educational programs. He began writing one of these while still at Daventry, the ''Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion

The ''Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion'', written by 18th-century English Dissenting minister and polymath Joseph Priestley, is a three-volume work designed for religious education published by Joseph Johnson between 1772 and 1774. ...

''. However, he did not publish the work until 1772, when he was at Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popula ...

. In an effort to increase and stabilize membership at his church there, he taught three religious education classes. He subdivided the young people of the congregation into three categories: young men from 18–30 to whom he taught "the elements of natural and revealed religion" (young women may or may not be included in this group); children under 14 to whom he taught "the first elements of religious knowledge by way of a short catechism in the plainest and most familiar language possible"; and "an intermediate class" to whom he taught "knowledge of the Scriptures only." Unlike the later Sunday schools established by Robert Raikes

Robert Raikes ("the Younger") (14 September 1736 – 5 April 1811) was an English philanthropist and Anglican layman. He was educated at The Crypt School Gloucester. He was noted for his promotion of Sunday schools.

Family

Raikes was born at ...

, Priestley aimed his classes at middle-class Rational Dissenters; he wanted to teach them "the principles of natural religion and the evidences and doctrine of revelation in a regular and systematic course," something their parents could not provide.

Priestley wrote texts for the courses he envisioned: ''A Catechism for Children and Young Persons'' (1767), which went through eleven English-language editions; and ''A Scripture Catechism, consisting of a Series of Questions, with References to the Scriptures instead of Answers'' (1772), which went through six British editions by 1817. He aimed to write non-sectarian ''Catechisms'', but in this he failed. He offended many orthodox readers by focusing on God's benevolence instead of on Adam's sin and Christ's atonement. Priestley implemented this same system of religious instruction over a decade later in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

, when he became a minister at New Meeting.Schofield, Vol. 1, 170-1; Gibbs, 37; Watts, 94.

Notes

Bibliography

For a complete bibliography of Priestley's works, see thelist of works by Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) was a British natural philosopher, Dissenting clergyman, political theorist, theologian, and educator. He is best known for his discovery, simultaneously with Antoine Lavoisier, of oxygen gas.

A member of marginal ...

.

*Gibbs, F. W. ''Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth''. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

*Jackson, Joe, ''A World on Fire: A Heretic, An Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen''. New York: Viking, 2005. .

*McLachlan, John. ''Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733-1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman''. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books Ltd., 1983. .

*McLachlan, John. "Joseph Priestley and the Study of History." ''Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society'' 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

*Schofield, Robert E. ''The Enlightenment of Joseph Priestley: A Study of his Life and Work from 1733 to 1773''. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997. .

*Schofield, Robert E. ''The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804''. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004. .

*Sheps, Arthur. "Joseph Priestley's Time ''Charts'': The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England." ''Lumen'' 18 (1999): 135–154.

*Thorpe, T.E. ''Joseph Priestley''. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

*Uglow, Jenny. ''The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World''. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. .

*Watts, R. "Joseph Priestley and education." ''Enlightenment and Dissent'' 2 (1983): 83–100.

External links

The Joseph Priestley Society

- Comprehensive site which includes a bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

Full-text online links

A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism

(full text from google books)

Lectures on General History, and General Policy

(full text from google books)

Heads of Lectures on Course of Experimental Philosophy

(full text from google books)

A Description of a New Chart of History

(full text from google books)

Letters to Dr. Horne, Dean of Canterbury, to the Young Men who are in a Course of Education for the Christian Ministry at the Universities of Oxford or Cambridge

(full text from google books) {{DEFAULTSORT:Joseph Priestley And Education English grammar History education Religion and education History of education in England