Joseph O'Doherty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph O'Doherty (24 December 1891 – 10 August 1979) was an Irish teacher, barrister, revolutionary, politician, county manager, member of the

When he qualified as a teacher, Ireland was in the middle of the renewed expectations of

When he qualified as a teacher, Ireland was in the middle of the renewed expectations of

In 1913 O'Doherty joined the

In 1913 O'Doherty joined the

O'Doherty and his brother Seamus were arrested a few days after the Easter Rising and taken in handcuffs to Dublin where they were imprisoned in

O'Doherty and his brother Seamus were arrested a few days after the Easter Rising and taken in handcuffs to Dublin where they were imprisoned in

O'Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the

O'Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the

In 1922–1924 and 1925–1926,

In 1922–1924 and 1925–1926,

First Dáil

The First Dáil ( ga, An Chéad Dáil) was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 1919 to 1921. It was the first meeting of the unicameral parliament of the revolutionary Irish Republic. In the December 1918 election to the Parliament of the United ...

and of the Irish Free State Seanad.

Family

Joseph O'Doherty's father Michael O'Doherty was a prosperous entrepreneur from Gortyarrigan in the parish of Desertegney at the side of Raghin Beg mountain on theInishowen

Inishowen () is a peninsula in the north of County Donegal in Ireland. Inishowen is the largest peninsula on the island of Ireland.

The Inishowen peninsula includes Ireland's most northerly point, Malin Head. The Grianan of Aileach, a ringfort ...

peninsula, County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrconn ...

. When he got married, Michael moved from Gortyarrigan to the town of Derry where he owned a hansom cab business and a chain of butcher shops, kept racing horses, traded in cattle, and supplied meat until 1916 for the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fra ...

fort at Dunree.

Joseph's mother Rose O'Doherty (née McLaughlin) inspired him to become a revolutionary. O'Doherty was born at his parents' home at 14 Little Diamond in the Bogside district of Derry on Christmas Eve 1891. His brother, Séamus

() is an Irish and Scottish male given name, of Hebrew origin via Latin. It is the Irish equivalent of the name James. The name James is the English New Testament variant for the Hebrew name Jacob. It entered the Irish and Scottish Gaelic lan ...

, was also a member of the IRB and took part in the events of the Easter Rising.

Education

He was first educated at St Columb's College grammar school in Derry. He then studied at St Patrick's College, Drumcondra, (Dublin) where he qualified as a primary school teacher in 1912. When he qualified as a teacher, Ireland was in the middle of the renewed expectations of

When he qualified as a teacher, Ireland was in the middle of the renewed expectations of Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

and the opposing activities of Sir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicitor ...

, the leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and ...

and of the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule m ...

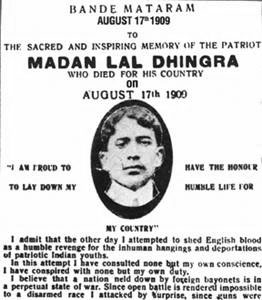

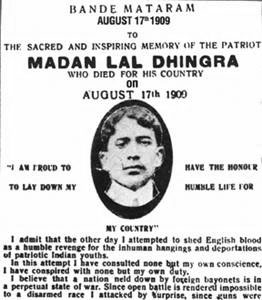

. The young Joseph became well-soaked in revolutionary literature – partly through his interest in education which led him to read the articles and poetry of Pádraic Pearse – and he became a subscriber to the Indian revolutionary newspaper Bande Mataram

''Vande Mataram'' (Sanskrit: वन्दे मातरम् IAST: , also spelt ''Bande Mataram''; বন্দে মাতরম্, ''Bônde Mātôrôm''; ) is a poem written in sanskritised Bengali by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in the ...

.

By 1913/14, he was completely disillusioned with the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

of John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as leader of the moderate Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) from ...

. With his teacher-training completed, O'Doherty taught for six months. He loved teaching and wanted to continue in this field, but was soon reluctantly persuaded by his elder brother Séamus O'Doherty to join the republican movement. He then joined the firm of Lawlor Ltd., of Ormonde Quay, Dublin, one of whose directors was Cathal Brugha, who subsequently became the first chairman and President of Dáil Éireann

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

and the first Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army

Several people are reported to have served as Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army () in the organisations bearing that name. Due to the clandestine nature of these organisations, this list is not definitive.

Chiefs of Staff of the Irish ...

(the Old IRA).

He later studied at Trinity College Dublin

, name_Latin = Collegium Sanctae et Individuae Trinitatis Reginae Elizabethae juxta Dublin

, motto = ''Perpetuis futuris temporibus duraturam'' (Latin)

, motto_lang = la

, motto_English = It will last i ...

and was enrolled at King's Inns where he qualified as a Barrister-at-Law.

Rebellion

Irish Volunteers

In 1913 O'Doherty joined the

In 1913 O'Doherty joined the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

when the organisation met at the Rotunda in Dublin. He was a member of the Volunteers 'B' Company, 3d Battalion, Dublin.

At the start of World War I, over 90% of the Irish Volunteers joined the National Volunteers

The National Volunteers was the name taken by the majority of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' role in World War I.

Origins

The Nati ...

and thus enlisted in the 10th (Irish) Division

The 10th (Irish) Division, was one of the first of Kitchener's New Army K1 Army Group divisions (formed from Kitchener's 'first hundred thousand' new volunteers), authorized on 21 August 1914, after the outbreak of the Great War. It included ...

and 16th (Irish) Division

The 16th (Irish) Division was an infantry division of the British Army, raised for service during World War I. The division was a voluntary 'Service' formation of Lord Kitchener's New Armies, created in Ireland from the ' National Volunteers' ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

to fight in Europe. This left the Irish Volunteers with a rump estimated at 10–14,000 members.

The Volunteers fought for Irish independence in 1916's Easter Rising, and were joined by the Irish Citizen Army, Cumann na mBan

Cumann na mBan (; literally "The Women's Council" but calling themselves The Irishwomen's Council in English), abbreviated C na mB, is an Irish republican women's paramilitary organisation formed in Dublin on 2 April 1914, merging with and d ...

and Fianna Éireann

Na Fianna Éireann (The Fianna of Ireland), known as the Fianna, is an Irish nationalist youth organisation founded by Constance Markievicz in 1909, with later help from Bulmer Hobson. Fianna members were involved in setting up the Irish Volun ...

to form the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

a.k.a. the Old IRA.

O'Doherty founded branches of the Volunteers from Crossmaglen

Crossmaglen (, ) is a village and townland in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It had a population of 1,610 in the 2011 Census and is the largest village in South Armagh. The village centre is the site of a large Police Service of Northern Ire ...

to Malin Head

Malin Head ( ga, Cionn Mhálanna) is the most northerly point of mainland Ireland, located in the townland of Ardmalin on the Inishowen peninsula in County Donegal. The head's northernmost point is called Dunalderagh at latitude 55.38ºN. It is ...

. He was given command of the Derry Volunteers in the buildup to 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the ...

and remained a member of the Executive until 1921.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

Shortly after joining the Volunteers, Joseph's elder brother Seamus informed him of the existence of the secret revolutionary party called theIrish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB) of which he was a member. When Seamus asked Joseph for his opinion of secret organisations, Joseph replied that he thought secrecy was necessary to safeguard plans. Until then, he had no idea that the IRB existed and that his brother was a member. He was asked to join and was initiated into it by a close friend of the O'Doherty family, Seán Mac Diarmada

Seán Mac Diarmada (27 January 1883 – 12 May 1916), also known as Seán MacDermott, was an Irish republican political activist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916, which he helped to organi ...

who was the manager of the radical newspaper Irish Freedom. O'Doherty remained a member of the IRB until after the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the ...

, and was specially mobilised by the IRB for the Howth Road and Killcoole gun-runnings.

Gun-running

In 1914, O'Doherty took part in the two audacious gun-running events at Howth and Kilcoole. The first landing took place on 26 July 1914 at Howth, when Erskine Childers and his wifeMolly Childers

Mary Alden Childers ( Osgood; 14 December 1875– 1 January 1964), known as Molly Childers, was an American-born Irish writer and nationalist. A daughter of Dr Hamilton Osgood and Margaret Cushing Osgood of Beacon Hill, Boston, Massachusetts, ...

smuggled 1,500 single-shot Mauser 71 rifles from Hamburg, Germany for the Irish Volunteers aboard their 51 ft gaff yacht, the Asgard

In Nordic mythology, Asgard (Old Norse: ''Ásgarðr'' ; "enclosure of the Æsir") is a location associated with the gods. It appears in a multitude of Old Norse sagas and mythological texts. It is described as the fortified home of the Æsir ...

. The guns, dating from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 were still functioning. They were later used in the attack on the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin during the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the ...

.

O'Doherty unloaded the first consignment of around 900 Mausers and 29,000 bullets off the Asgard along with Bulmer Hobson

John Bulmer Hobson (14 January 1883 – 8 August 1969) was a leading member of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) before the Easter Rising in 1916.D.J. Hickey & J. E. Doherty, ''A New Dictionary of Irish History fro ...

, Douglas Hyde

Douglas Ross Hyde ( ga, Dubhghlas de hÍde; 17 January 1860 – 12 July 1949), known as (), was an Irish academic, linguist, scholar of the Irish language, politician and diplomat who served as the first President of Ireland from June 1938 t ...

, Darrell Figgis

Darrell Edmund Figgis ( ga, Darghal Figes; 17 September 1882 – 27 October 1925) was an Irish writer, Sinn Féin activist and independent parliamentarian in the Irish Free State. The little that has been written about him has attempted to highl ...

, Peadar Kearney, Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh ( ga, Tomás Anéislis Mac Donnchadha; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising ...

and others. This happened in public view in broad daylight and quickly led to police and military intervention. While accompanying the weapons convoy on the road from Howth to Dublin, O'Doherty broke the butt of his gun in a skirmish with the security forces, but successfully evaded them. As the King's Own Scottish Borderers

The King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. On 28 March 2006 the regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Scots, the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Margaret's O ...

infantry regiment returned to barracks, they were accosted at Bachelors Walk by civilians who threw stones and exchanged insults with the regulars. The soldiers bayoneted one man and shot into the unarmed crowd, resulting in four dead and 38 wounded civilians in what became known as the Bachelor's Walk massacre.

O'Doherty was also involved in the second gun-running the following week, around midnight on 1 August 1914, when the volunteers landed 600 more German-made Mauser 71 single-shot rifles and 20,000 rounds of ammunition off the Chotah at the much more discretely located beach at Kilkoole, Co. Wicklow, and spirited them away under cover of darkness. O'Doherty was in the lorry that delivered that consignment to a cache at St. Enda's School (which Padraic Pearse had founded in 1908) and which was now located at The Hermitage at Rathfarnam in the foothills of the Dublin Mountains where Pearse was waiting for them on the steps.

Other operations

In 1914 O'Doherty was one of a special group of IRB men mobilised under William Conway to frustrate a British Army recruiting meeting that was to be held at the Mansion House in Dublin. They were mobilised inParnell Square

Parnell Square () is a Georgian square sited at the northern end of O'Connell Street in the city of Dublin, Ireland. It is in the city's D01 postal district.

Formerly named ''Rutland Square'', it was renamed after Charles Stewart Parnell (1 ...

with about 24 hours' rations and with arms, but the word came that a large group of British soldiers were in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the s ...

and had taken over control of the area so that it would be impossible to get in, and the operation was called off.

In 1914, O'Doherty took part in a little-known operation in which the Irish Volunteers seized part of the 216 tonnes of guns and ammunition that had been delivered to the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaign ...

from the German Empire, in the Larne gun-running incident on 24 and 25 April of that year.

Soon afterwards, while attending a play at a theatre in Dublin with another member of the Volunteer Executive, O'Doherty was arrested in the lobby during the intermission. As they were about to be marched up to Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle ( ga, Caisleán Bhaile Átha Cliath) is a former Motte-and-bailey castle and current Irish government complex and conference centre. It was chosen for its position at the highest point of central Dublin.

Until 1922 it was the s ...

, O'Doherty realised that they would both be tortured to reveal the location of the weapons caches and other information. Taking advantage of the soldiers being distracted by the crowd of onlookers who had gathered outside the theatre, O'Doherty ducked under the soldiers’ bayonets, leapt onto a passing tram, and escaped into the night. Days later, his friend's body was found, dismembered, at the Featherbed in the nearby Dublin mountains.

O'Doherty remained in Dublin until 1915 when his father asked him to return to Derry to manage the chain of butchers' shops business which he had recently bought there. After moving back to Derry, he joined the Derry branch of the Volunteers with Patrick McCartan

Patrick McCartan (13 May 1878 – 28 March 1963) was an Irish republican and politician. He served the First Dáil (1919–1921) on diplomatic missions to the United States and Soviet Russia. He returned to public life in 1948, serving in Sean ...

who had previously edited the journal Irish Freedom in Pennsylvania, USA, and who was now in control of the IRB in the North. At McCartan's request in January 1916, O'Doherty took a delivery of arms via a trader named Edmiston & Scotts. The Derry Volunteer group also obtained quantities of .303 rifle ammunition which were delivered to Dublin, frequently by O'Doherty and members of his family.

1916 Easter Rising

O'Doherty was charged by the Irish Volunteers Executive to co-ordinate the Easter Rising in Derry, and to wait for the signal to begin the planned operation. But to his great dismay on Easter Sunday morning, the Sunday Independent newspaper published a last-minute countermanding order by the Volunteers Chief of Staff,Eoin MacNeill

Eoin MacNeill ( ga, Eoin Mac Néill; born John McNeill; 15 May 1867 – 15 October 1945) was an Irish scholar, Irish language enthusiast, Gaelic revivalist, nationalist and politician who served as Minister for Education from 1922 to 1925, Cea ...

advising the Volunteers not to take part. Although the rising did take place in Dublin, the Derry Volunteers did not participate due to confusion over this countermanding order and a subsequent breakdown in communications with Dublin.

The rising took place mainly in Dublin where it caused considerable damage. Although volunteer groups also took action in Kerry, Cork, Wexford, Kildare, Donegal, and Galway, a considerable section of the Volunteers did not participate – partly as a result of MacNeill's cancellation.

A total of 3,430 men and 79 women were arrested. 187 were tried under a series of court-martials, and 90 were sentenced to death. 14 of them including all seven signatories of the Proclamation and were executed by firing squad at Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol ( ga, Príosún Chill Mhaighneann) is a former prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a museum run by the Office of Public Works, an agency of the Government of Ireland. Many Irish revolutionaries, including the lead ...

between 3 and 12 May. The most prominent leader to escape execution was the Commandant of the 3rd Battalion, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

, partly because of his American birth. He subsequently became President of the Irish Republic.

Capture and prison

O'Doherty and his brother Seamus were arrested a few days after the Easter Rising and taken in handcuffs to Dublin where they were imprisoned in

O'Doherty and his brother Seamus were arrested a few days after the Easter Rising and taken in handcuffs to Dublin where they were imprisoned in Richmond Barracks

Richmond Barracks was a British Army barracks in Inchicore, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a cultural centre.

History

The barracks, which were named after Charles Lennox, 4th Duke of Richmond, were completed in 1810 and first occupied by the Briti ...

in Dublin. O'Doherty was sent soon afterwards to the Abercorn Barracks

Abercorn Barracks, sometimes referred to as Ballykinlar Barracks or Ballykinler Barracks, is a former military base in Ballykinler in County Down, Northern Ireland. The surrounding training area is retained by the Ministry of Defence.

Early histo ...

at Ballykinlar in County Down. He spent time at Belfast gaol, Derry gaol

Derry Gaol, also known as Londonderry Gaol, refers to one of several gaols (prisons) constructed consecutively in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. Derry Gaol is notable as a place of incarceration for Irish Republican Army (IRA) m ...

, and was subsequently moved to Wakefield Prison in West Yorkshire (England), Wormwood Scrubs

Wormwood Scrubs, known locally as The Scrubs (or simply Scrubs), is an open space in Old Oak Common located in the north-eastern corner of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in west London. It is the largest open space in the borough, ...

in London and the Frongoch internment camp

Frongoch internment camp at Frongoch in Merionethshire, Wales was a makeshift place of imprisonment during the First World War and the 1916 Easter Rising.

History

1916 the camp housed German prisoners of war in a yellow distillery and cru ...

in Wales, where he was sent as an Irish prisoner of war along with 1,800 others including Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

. Although he was not imprisoned in Mountjoy Gaol

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, Príosún Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History

...

, he was one of the last people to speak to Pádraig Pearse (1879–1916) there (either as a visitor or through a window) before the latter was executed by firing squad.

In a filmed interview decades later, O'Doherty said "Those of us who were arrested were transferred in handcuffs to Richmond Barracks in Dublin, and subsequently transferred to England. Our crowd were marched between the files of a British regiment through the streets of Dublin, and several sections were stoned." First Dail

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

in 1919. Among those interned there, 30 would become TDs (including O'Doherty, Richard Mulcahy, Michael Collins, Seán T. O'Kelly) and Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

, two of whom later became Presidents of Ireland. After a few weeks, however, their prisoner of war status and privileges were withdrawn, and O'Doherty was released in early August 1916

O'Doherty went back to Derry and helped his father re-open the head office of his family business, and then in December he was contacted and asked to come up and manage the first republican paper that was published in 1916, called "The Phoenix".

German Plot

On the night of 16–17 May 1918, O'Doherty was arrested along with 150 Sinn Féin leaders concerning the so-called German Plot. This wasdisinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the L ...

campaign of black propaganda

Black propaganda is a form of propaganda intended to create the impression that it was created by those it is supposed to discredit. Black propaganda contrasts with gray propaganda, which does not identify its source, as well as white propagan ...

organised by the Dublin Castle administration to discredit Sinn Féin by falsely accusing it of conspiring with the German Empire to start an armed insurrection and invade in Ireland during World War I. This alleged conspiracy which would have diverted the British war effort, was used to justify the internment of Sinn Féin leaders, who were actively opposing attempts to introduce conscription in Ireland. O'Doherty was put in Arbour Hill gaol , but was released in 1917. He became a member of the executive of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respon ...

that year.

Politics

1918 general election

In the aftermath of the Easter Rising of 1916, theSinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

party (founded by Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

in 1905), was reorganised and grew into a nation-wide movement, calling for the establishment of an Irish Republic with elected members abstaining from Westminster and instead establishing a separate and independent Irish parliament. The party contested the 14 December 1918 general election, called following the dissolution of the United Kingdom Parliament, and swept the country winning 73 of the 105 Irish seats.

O'Doherty, now aged 26, was elected as Sinn Féin Member of the UK Parliament for Donegal North, defeating his only opponent (from the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

). Acting on their pledge not to sit in the Westminster parliament, but instead to set up an Irish legislative assembly, 28 of the newly elected Sinn Féin representatives met and constituted themselves as the first Dáil Éireann, describing themselves not as a MPs but as Teachtaí Dála (TDs). The remaining Sinn Féin TDs were either in prison or unable to attend for other reasons. The establishment of the First Dáil co-incidentally occurred on the same day as the outbreak

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

of what came to be known as the Irish War of Independence between the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief th ...

and the British state's security forces. Although Sinn Féin candidates had not stood for election on an explicit platform of armed conflict with British state and the initial military actions were taken without the authority of the Dáil, the background of almost all TDs as revolutionary militants saw the escalation of the Irish revolutionary period into warfare.

First Dáil

The first Dáil met in the Round Room of the Mansion House in Dublin on 21 January 1919. The Dáil asserted the exclusive right of the elected representatives of the Irish people to legislate for the country. The Members present adopted aProvisional Constitution A provisional constitution, interim constitution or transitional constitution is a constitution intended to serve during a transitional period until a permanent constitution is adopted. The following countries currently have,had in the past,such a c ...

and approved the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

. The Dáil also approved a Democratic Programme, based on the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

, and read and adopted a Message to the Free Nations of the World.

Following the simultaneous outbreak of the Irish War of Independence in January 1919, the British government decided to suppress the Dáil, and on 10 September 1919 Dáil Éireann was declared a dangerous association and was prohibited. Defying the law, however, the Dáil continued to meet in secret.

O'Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the

O'Doherty was re-elected at the 1921 general election and opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

which led to the partition of Ireland. In a Dáil meeting, he made the following statement:

"I know that the people in North Donegal at the present moment would accept this Treaty, and I think it is fair to the people of North Donegal that I should make that known; but they are accepting it under duress and at the point of the bayonet, and as a stop to terrible and immediate war. Like my co-Deputy from Tír Chonaill I came to this Session of Dáil Éireann with a mind that was open to conviction against these prejudices that I had; no argument that has been produced by those who are for this Treaty has made any influence on me; I see in it the giving away of the whole case of Irish independence; I am prepared to admit that the mandate I got from the constituents of North Donegal was one of self-determination; and it is a terrible thing and a terrible trial to have men in this Dáil interpreting that sacred principle here against the interests of the people. It is not peace they are getting; it is not the liberty they are getting which they are told they are getting, and they know it; and I will tell them honestly if I go to North Donegal again what they are getting."

He was subsequently re-elected as Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin and as an abstentionist republican in 1922 and 1923 respectively.

Civil War

Following the signing of theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, the Irish Civil War broke out between the pro-treaty Provisional Government led by Michael Collins (which became the Free State in December 1922) and the anti-treaty opposition (which was supported by O'Doherty) and which rejected the treaty as a betrayal of the Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

. This war lasted from 28 June 1922 to 24 May 1923. Many of those who fought on both sides in the conflict had been members of the Irish Republican Army during the War of Independence, including family members who fought each other, with atrocities and revenge killings on both sides. The war came to an end a year and a month after it began, when the Free State forces defeated those who opposed the Treaty.

In the US

In 1922–1924 and 1925–1926,

In 1922–1924 and 1925–1926, Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

sent him on two Republican missions to the US with Seán T. O'Kelly and Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician. He was chief of staff of the Anti-Treaty IRA at the end of the Irish Civil War. Aiken later served as Tánaiste from 1965 to 1969 and Minister ...

to lobby and raise funds for the civil war. He crossed the Atlantic aboard a luxury liner, where during a dinner party hosted by the ship's captain, another guest who was a world-famous boxer challenged him to a fight to entertain the passengers, but O'Doherty had to decline in order to avoid drawing attention to himself. Travelling under a false passport as a Presbyterian minister to Canada, he entered the US by crossing the border with help from Irish whiskey smugglers (this was during the Prohibition era

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic be ...

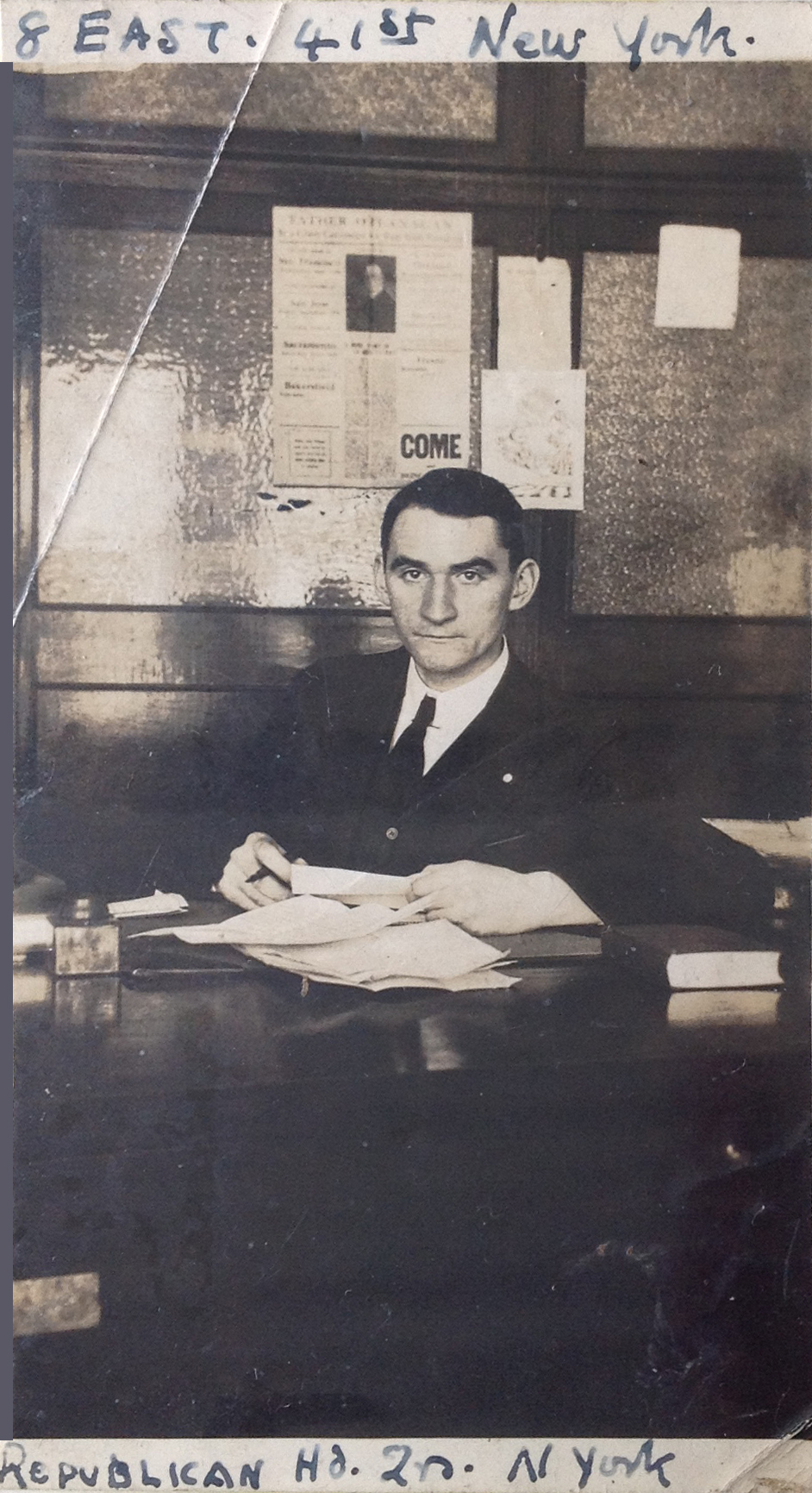

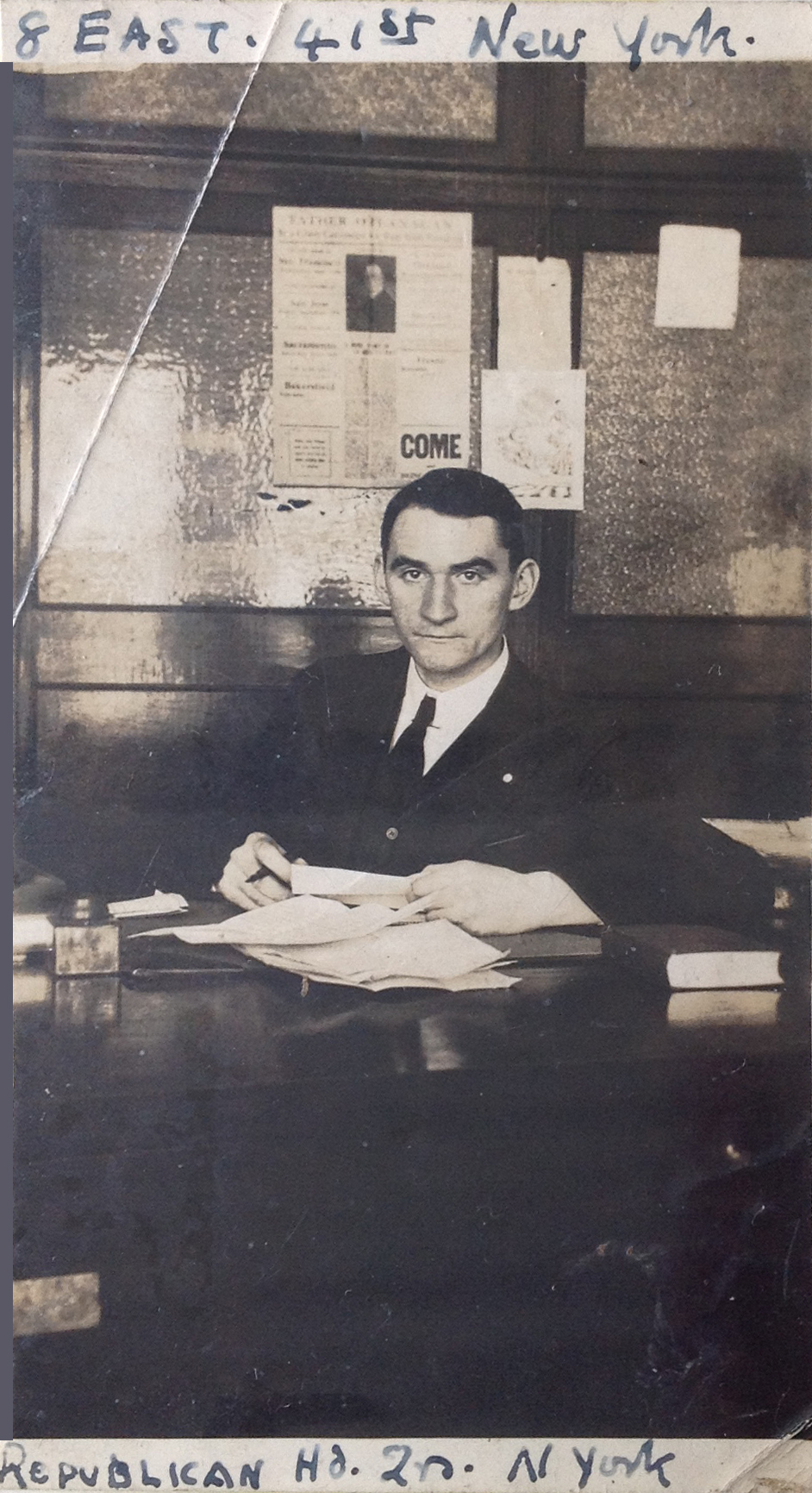

when alcohol was illegal in the USA). He visited every capitol in all 48 contiguous US states, dropped thousands of fundraising leaflets from a biplane flying between Manhattan skyscrapers in New York, and lived there with his wife Margaret O'Doherty in her flat at Columbus Circle, while she practised medicine at St. Vincent's hospital in Greenwich Village. He had an office at 8 East 41st. Street in Manhattan, New York. On 17 October 1924 the British Consulate General in New York issued him with a new British Passport under his own name. His related adventures included descending the Grand Canyon on horseback, being invited to join a police raid on an opium den in San Francisco's Chinatown.

Co-founding Fianna Fáil

In 1926 O'Doherty he left the Sinn Féin party'sArdfheis

or ''ardfheis'' ( , ; "high assembly"; plural ''ardfheiseanna'') is the name used by many Irish political parties for their annual party conference. The term was first used by Conradh na Gaeilge, the Irish language cultural organisation, for i ...

with Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of govern ...

and became a founder member of the new Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christia ...

party. He lost his seat at the June 1927 general election but was re-elected again to the Dáil in the 1933 general election.

He was elected to the Seanad Éireann

Seanad Éireann (, ; "Senate of Ireland") is the upper house of the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature), which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann (the lower house).

It is commonly called the Seanad or Senate and its memb ...

in 1928, serving as one of Fianna Fáil's first six elected Senators under the leadership of Joseph Connolly.

From 1929 to 1933 served as the county manager of Carlow and Kildare

Kildare () is a town in County Kildare, Ireland. , its population was 8,634 making it the 7th largest town in County Kildare. The town lies on the R445, some west of Dublin – near enough for it to have become, despite being a regional ce ...

, where he used his knowledge of dowsing

Dowsing is a type of divination employed in attempts to locate ground water, buried metals or ores, gemstones, oil, claimed radiations ( radiesthesia),As translated from one preface of the Kassel experiments, "roughly 10,000 active dowsers in ...

to find water supplies for local towns.

In 1936 O'Doherty successfully sued Ernie O'Malley for libel. The incident in question involved a raid Michael Collins had proposed to take place on 1 October 1919 at Moville, County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrconn ...

. O'Malley, in his book ''On Another Man's Wound,'' had implied that O'Doherty had refused to go. In fact, it had been agreed, without O'Doherty's intervention, that it would be inappropriate for a member of the Dáil to be involved.Richard English, ''Ernie O'Malley: IRA Intellectual'', p. 44, Oxford University Press, 1999,

Personal life

In 1918, O'Doherty married Margaret (Mairéad) Claire Susan Irvine (1893–1986), the same year she graduated as a medical doctor. She was born in Maguiresbridge, County Fermanagh. She studied medicine here?and after marrying O'Doherty, was appointed Chief Medical Officer of Derry, a post she occupied from 1919 to 1921, during the last year working without pay because she refused to take the Oath of Allegiance Oath of Allegiance to theKing George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

.

O'Doherty and his wife had five children: Brid O'Doherty (1919–2018), a member of the Saint Louis order of nuns; Fíona O'Callaghan (1921–2003); Roisín McCallum (1924–2018); Deirdre O'Doherty (a nun with the Poor Clare order (1927–2007) in Newry; and David O'Doherty (1935–2010) a painter and traditional Irish musician.''Nun who became an expert in French Romanticism – Brid O'Doherty' Obituaries, Irish Times, Weekend Edition, 4 August 2018.''

He died in 1979, the third last surviving member of the First Dáil, and is buried along with his wife in the Republican plot in Glasnevin Cemetery

Glasnevin Cemetery ( ga, Reilig Ghlas Naíon) is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832. It holds the graves and memorials of several notable figures, and has a museum.

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasne ...

, Dublin.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Odoherty, Joseph 1891 births 1979 deaths Alumni of King's Inns Alumni of St Patrick's College, Dublin Early Sinn Féin TDs Fianna Fáil TDs Fianna Fáil senators Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Members of the 1928 Seanad Members of the 1931 Seanad Members of the 1st Dáil Members of the 2nd Dáil Members of the 3rd Dáil Members of the 4th Dáil Members of the 8th Dáil Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Donegal constituencies (1801–1922) People educated at St Columb's College People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side) Politicians from Derry (city) UK MPs 1918–1922