John Taylor Wood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Taylor Wood (August 13, 1830 – July 19, 1904) was an officer in the

Book (par view)

*

Book (par view)

*

Book (par view)

* *

Book (no view)

*

Book (par view)

*

Url

Book

Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

Halifax, Nova Scotia {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, John Taylor 1830 births 1904 deaths American emigrants to pre-Confederation Nova Scotia Canadian people of the American Civil War Confederate States Navy captains American people of English descent Confederate States Army officers Military history of Nova Scotia Northern-born Confederates People from Fort Snelling, Minnesota United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy officers Zachary Taylor family

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

and the Confederate Navy

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American ...

. He resigned from the U.S. Navy at the beginning of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, and became a "leading Confederate naval hero" as a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the Confederate Navy. He was a lieutenant serving aboard when it engaged in 1862, Bell, 2002, p.1 one of the most famous naval battles in Civil War and U.S. Naval history. Bell, 2002, p.41 He was caught in 1865 in Georgia with Confederate President Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

' party, but escaped and made his way to Cuba. From there, he got to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. Th ...

, where he settled and became a merchant. His wife and children joined him there, and more children were born in Canada, which is where he lived out the remainder of his life.

Early life

John Taylor Wood was the son and first child of Robert Crooke Wood fromRhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

, an army surgeon, and Ann Mackall Taylor, eldest daughter of Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, (who would become a major general in the United States Army, a hero of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, and who would serve as 12th president of the United States, 1849–1850). Robert Crooke Wood and Zachary Taylor served together in the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. Along with being the grandson of a U.S. president, John Taylor Wood was also the nephew of future Confederate president Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

, whose first wife, Sarah Knox Taylor (1814–1835), was the second daughter of Zachary Taylor and Margaret Mackall Smith.

Wood was born on August 13, 1830, Bell, 2002, p.12 at Fort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

then in the Northwest Territory near present-day St. Paul, Minnesota. Wood was delivered by his father and is claimed to have been the first white child born in Minnesota. Winstead, 2009 From 1832 until 1837, the Wood family lived at Fort Crawford located at the junction of the Mississippi and Wisconsin Rivers. Young Wood grew up in the frontier at the time of the Black Hawk War.

Marriage and family

Wood married Lola Mackubin in 1856, Bell, 2002, p.19 after getting his first assignments in the Navy. He and his wife had eleven children.Zachary Taylor Wood

Zachary Taylor Wood (November 27, 1860 – January 15, 1915''Who's Who'') was Assistant Commissioner with the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) and the commissioner of Yukon.

Early life

Born in Annapolis Naval Academy in 1860, where his father J ...

(1860–1915), the oldest son, became Acting Royal Canadian Mounted Police

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP; french: Gendarmerie royale du Canada; french: GRC, label=none), commonly known in English as the Mounties (and colloquially in French as ) is the federal and national police service of Canada. As poli ...

(RCMP) Commissioner and Commissioner of the Yukon Territory

The commissioner of Yukon (french: Commissaire du Yukon) is the representative of the Government of Canada in the Canadian federal territory of Yukon. The commissioner is appointed by the federal government and, in contrast to the governor gene ...

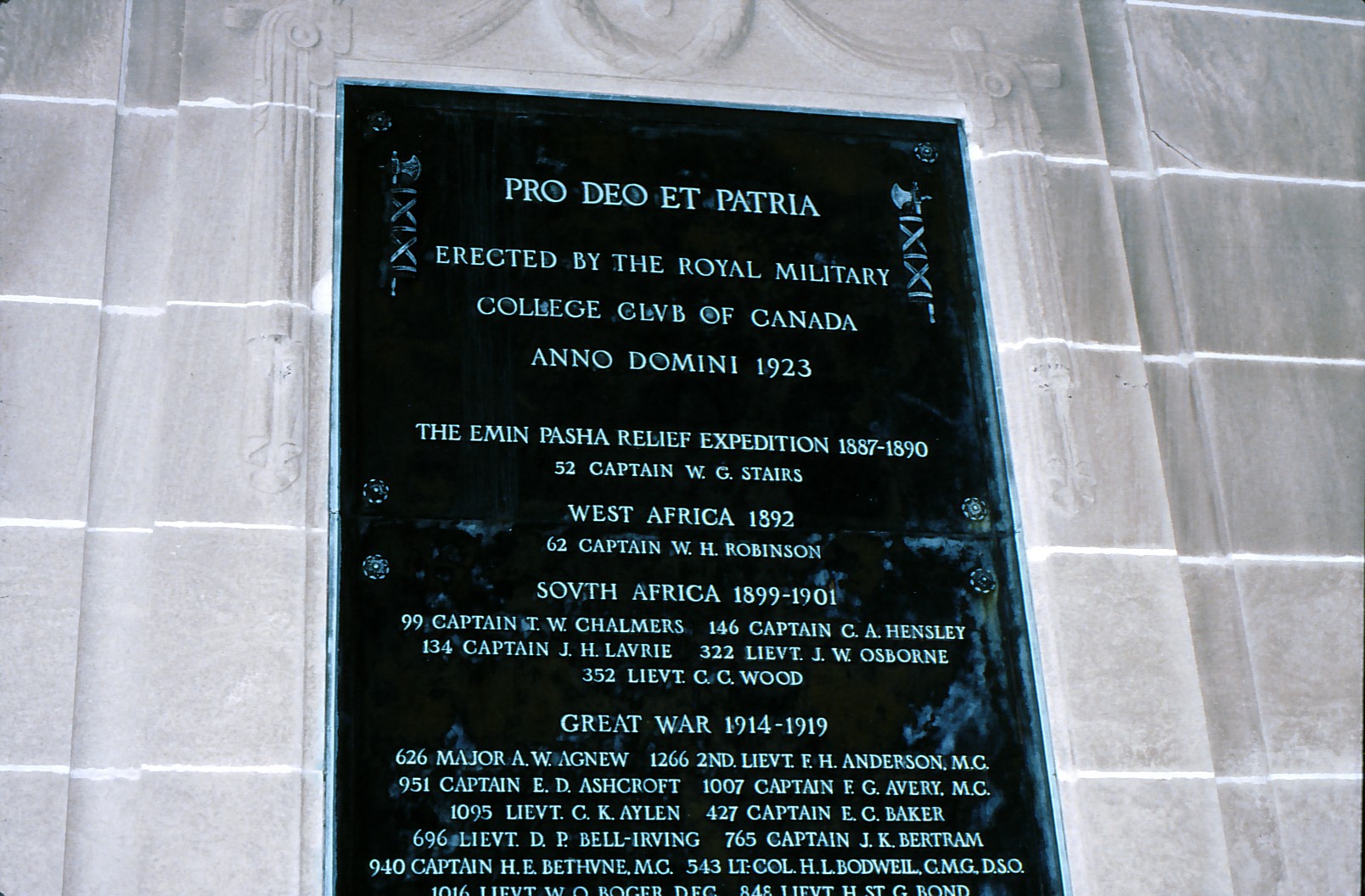

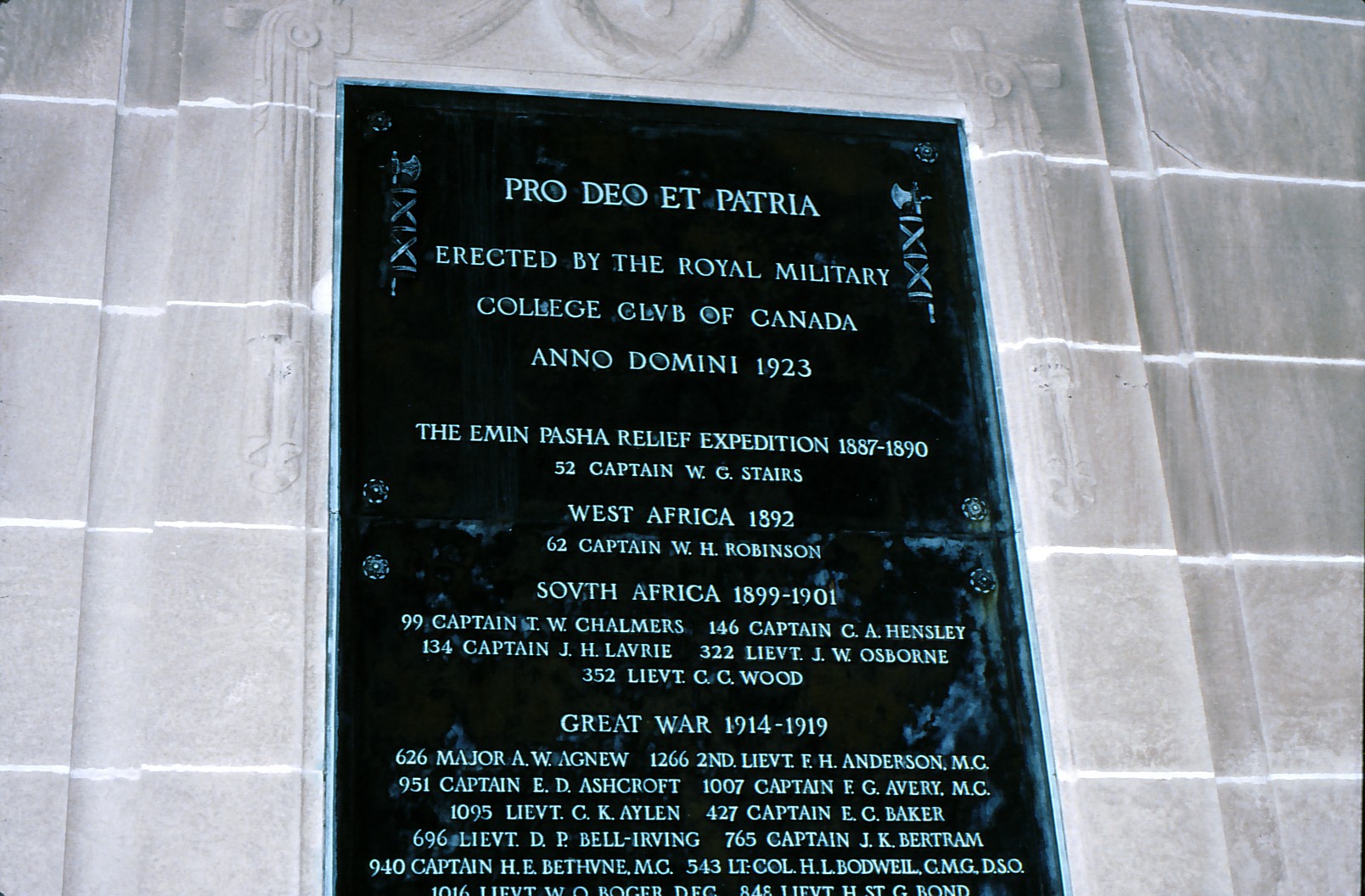

from 1902 to 1903. Charles Carroll Wood

Lieutenant Charles Carroll Wood (born 19 March 1876 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada – died 11 November 1899 in Belmont, South Africa) was the first Canadian Officer to die in the Second Boer War. As a member of a family that had distinguishe ...

(b. 1876 – d. 1899), the youngest son, graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada

'')

, established = 1876

, type = Military academy

, chancellor = Anita Anand ('' la, ex officio, label=none'' as Defence Minister)

, principal = Harry Kowal

, head_label ...

1896 (student #352). He served as a lieutenant for Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

in the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

and died in battle in 1899. He is memorialized on the Royal Military College Memorial Arch and the South African War Memorial (Halifax)

The South African War Memorial is a memorial located in the courtyard of Province House in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

History

On October 19, 1901, the Prince of Wales (the future George V) laid the cornerstone for the monument. (This was ...

.

Military career

Wood became a U.S. Navymidshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Af ...

on April 7, 1847. He joined the crew of the frigate which sailed to Brazil. Soon after he transferred to and sailed for the west coast of Mexico in 1847. Soon after arriving off the Mexican port of Mazzatan later that year Wood joined a thousand-sailor force that landed to capture the port city where he first experienced combat while commanding a gun crew. At the end of the Mexican War in 1848, Wood returned to ''Ohio'' and saw service in the newly acquired California territory

The history of California can be divided into the Native American period (about 10,000 years ago until 1542), the European exploration period (1542–1769), the Spanish colonial period (1769–1821), the Mexican period (1821–1848), and Un ...

during the gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New ...

. After serving at sea on ''Ohio'' for three years, Wood's ship returned to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

where he was given a three-month leave of absence. During his time aboard ''Ohio'', Zachary Taylor had become president.

Wood served for a time aboard ''Ohio'' alongside William Hall and later supported Hall's US Navy pension claim.

Suppression of African slave trade

Wood served at sea during the last part of theMexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, performing shore duty as a Naval Academy officer. During the last part of the war he sailed off the coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

suppressing the African slave trade

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were common in parts of Africa in ancient times, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Indian Ocean ...

and in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. He served aboard patrolling in the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is i ...

when it captured a Spanish slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

. His first command of a ship occurred when he was ordered to bring the captured Africans to Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

and set them free. He was responsible for his ship, his crew, and three hundred and fifty prisoners. The voyage lasted three weeks and was pitted against stormy seas but Wood succeeded in reaching Monrovia

Monrovia () is the capital city of the West African country of Liberia. Founded in 1822, it is located on Cape Mesurado on the Atlantic coast and as of the 2008 census had 1,010,970 residents, home to 29% of Liberia’s total population. As t ...

with his ship and passengers intact. The authorities in Liberia denied Wood the right to land his human cargo in the capital and he was forced on another one hundred and fifty mile voyage to Grand Bassa. Once again Wood was confronted by governmental authorities and was told he could not land his cargo of captured and would be slaves. However, this time he did not comply, asserted his authority, and landed his human cargo. Wood returned to ''Porpoise'' and at age 21 had gained confidence as a commander from the experience.

Other service

Wood graduated second in his class from theU.S. Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy is ...

in 1852. He then went on to serve on on voyage about the Mediterranean which last two years. ''Cumberland'' was a ship that he would later fight against as a Confederate officer in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. After returning to Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east ...

in September 1855, he received promotion to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

. Wood returned to Maryland and met Lola Mackubin, daughter of a prominent Maryland politician. They were married on November 26, 1856. Their daughter, Anne, was born on September 18, 1857. In 1858 he served as a gunnery officer for eighteen months aboard . His infant daughter died in 1859 while he was in service.

Civil War

Lieutenant Wood taught gunnery tactics at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, at the beginning of the Civil War. Due to his southern sympathies, he resigned his commission on April 2, 1861, and took up farming nearby. He later went toVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

and in October 1861, received a commission as a Confederate Navy first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

, where he was appointed as officer in the Confederate States Navy by October and assigned to in November. Field, 2011, p. 35

Following service with shore batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

on the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

, he became an officer in the newly converted ironclad

An ironclad is a steam-propelled warship protected by iron or steel armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. Th ...

CSS ''Virginia'' serving under Commander Buchanan Buchanan may refer to:

People

* Buchanan (surname)

Places Africa

* Buchanan, Liberia, a large coastal town

Antarctica

* Buchanan Point, Laurie Island

Australia

* Buchanan, New South Wales

* Buchanan, Northern Territory, a locality

* Bucha ...

. He was wounded in the Battle of Hampton Roads

The Battle of Hampton Roads, also referred to as the Battle of the ''Monitor'' and ''Virginia'' (rebuilt and renamed from the USS ''Merrimack'') or the Battle of Ironclads, was a naval battle during the American Civil War.

It was fought over t ...

. Wood commanded the stern pivot gun during the battle and fired the shot that seriously wounded Lieutenant John Lorimer Worden, captain of ''Monitor''.

In May 1862, after ''Virginia'' was destroyed, Wood assisted with the defense of Drewry's Bluff

Drewry's Bluff is located in northeastern Chesterfield County, Virginia, in the United States. It was the site of Confederate Fort Darling during the American Civil War. It was named for a local landowner, Confederate Captain Augustus H. Drewry, ...

, on the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesap ...

. During the next two years, Wood led several successful raids against Federal ships and also served as naval aide to Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confed ...

Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as ...

. Promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

in May 1863, he simultaneously held the rank of colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

in the cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

. These dual ranks, with his reputation for extraordinary daring and his family connections to Confederate leaders, allowed him to play an important liaison role between the South's army, navy and civil government.

In August 1864, Wood commanded , a Confederate commerce raider and blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usua ...

against U.S. shipping off the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

coast, capturing an astonishing 33 Union ships during a ten-day period off the coast of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. He received the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in February 1865. A few months later, as the Confederacy was disintegrating, he accompanied President Davis in his attempt to evade capture and leave the country.

Though briefly taken prisoner, Wood escaped to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

. He subsequently went to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. Th ...

, where he became a businessman. His wife and family joined him there, and they lived the rest of their lives in Nova Scotia. Wood died there on July 19, 1904. His obituary appeared in the ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' the next day. He is buried in Halifax's Camp Hill Cemetery.

Legacy

* Tallahassee Avenue, Tallahassee Elementary School, and Taylorwood Lane in Eastern Passage are named for Wood and his ship. * Halifax Street Names; An Illustrated Guide. p. 148See also

* Bibliography of American Civil War naval history *Military history of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia (also known as Mi'kma'ki and Acadia) is a Canadian province located in Canada's Maritimes. The region was initially occupied by Mi'kmaq. The colonial history of Nova Scotia includes the present-day Canadian Maritime provinces and th ...

* Canada in the American Civil War

At the time of the American Civil War (1861–1865), Canada did not yet exist as a federated nation. Instead, British North America consisted of the Province of Canada (parts of modern southern Ontario and southern Quebec) and the separate colo ...

References

Bibliography

*Book (par view)

*

Book (par view)

*

Book (par view)

* *

Book (no view)

*

Book (par view)

*

Url

Other sources

*Further reading

*Book

External links

* *Biography at the ''Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online''

Halifax, Nova Scotia {{DEFAULTSORT:Wood, John Taylor 1830 births 1904 deaths American emigrants to pre-Confederation Nova Scotia Canadian people of the American Civil War Confederate States Navy captains American people of English descent Confederate States Army officers Military history of Nova Scotia Northern-born Confederates People from Fort Snelling, Minnesota United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy officers Zachary Taylor family