John Rogers (Bible editor and martyr) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Rogers (c. 1505 – 4 February 1555) was an English

Here he met

Here he met

On 16 August 1553 he was summoned before the council and bidden to keep within his own house. His emoluments were taken away and his

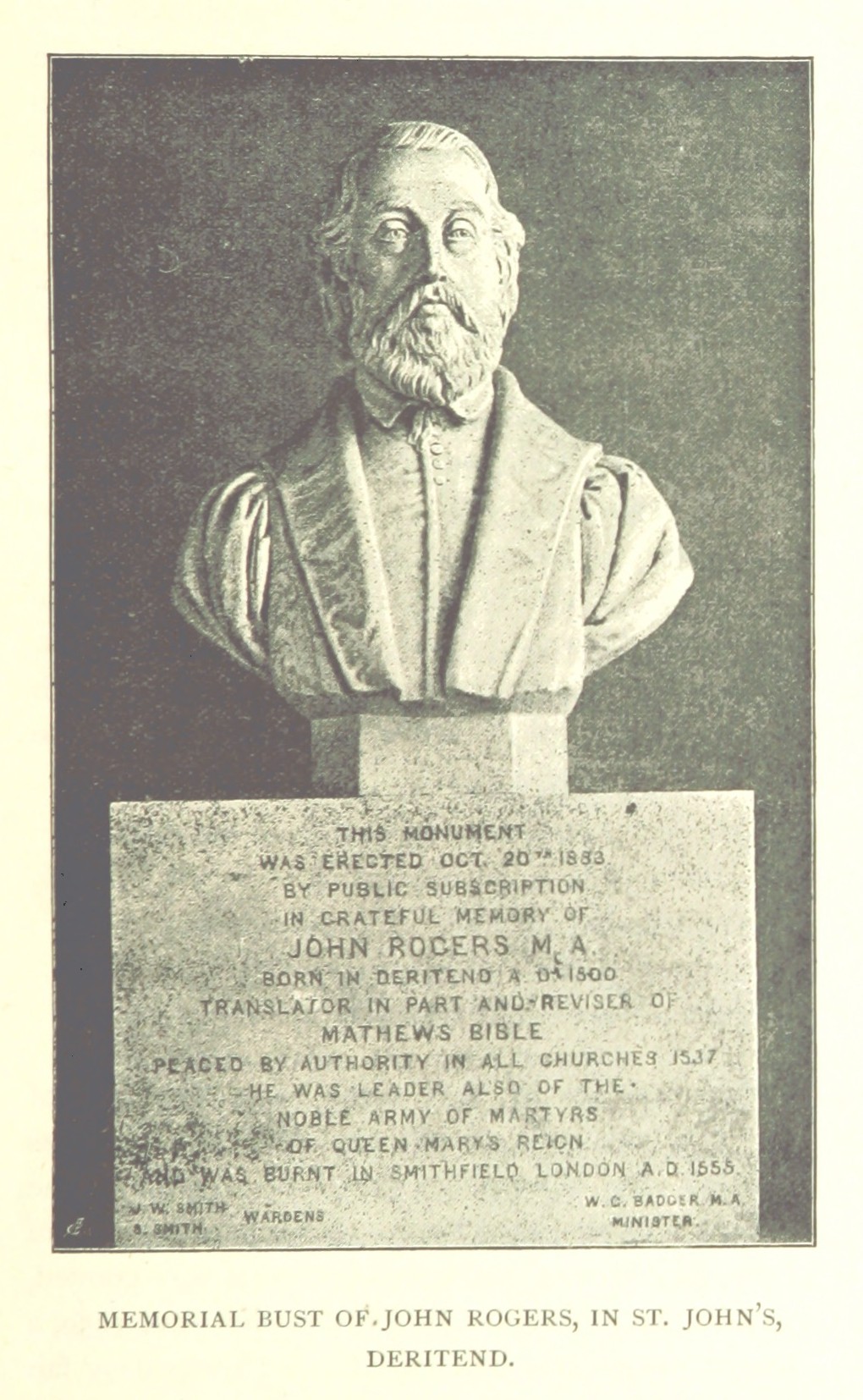

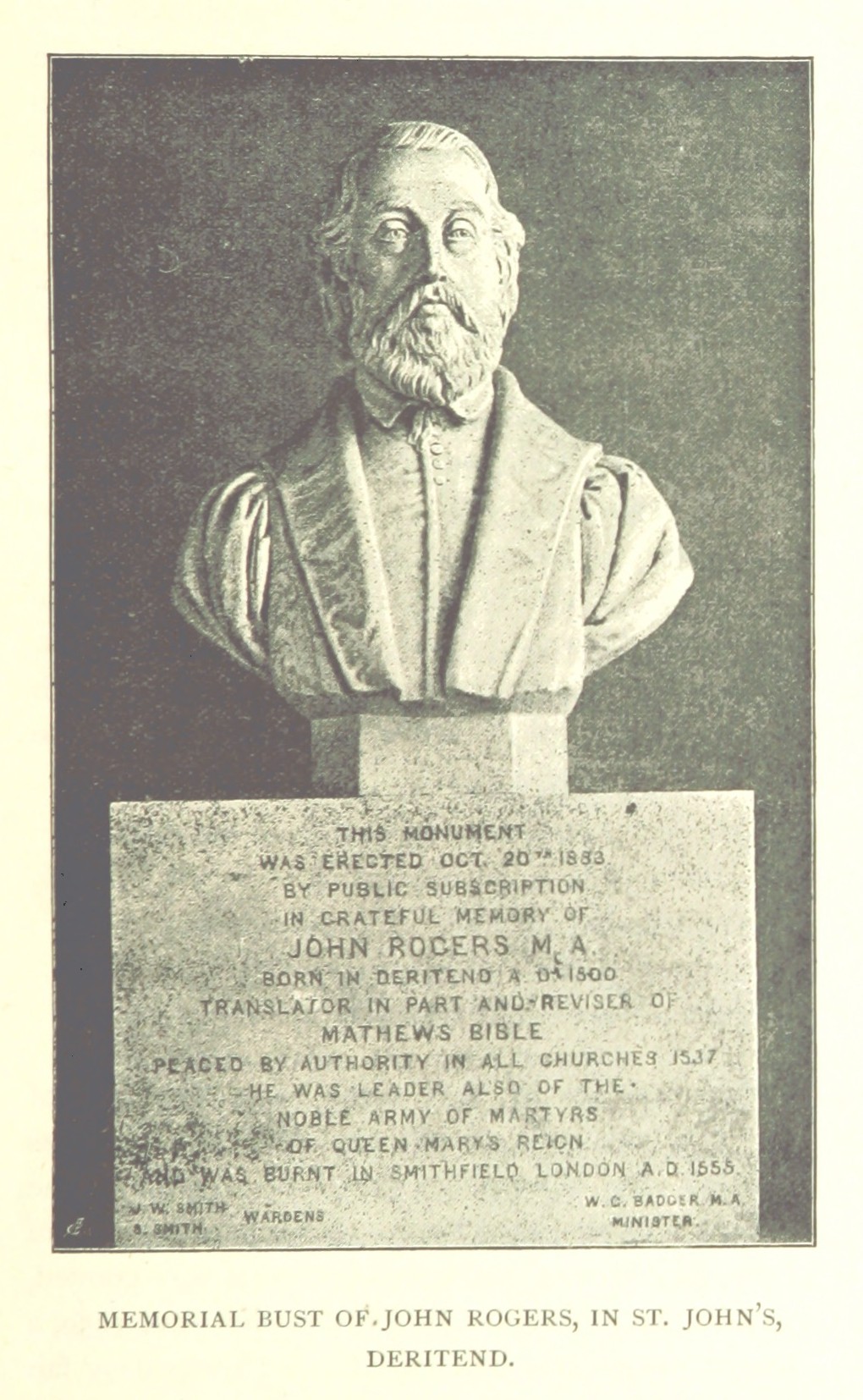

On 16 August 1553 he was summoned before the council and bidden to keep within his own house. His emoluments were taken away and his  A bust in his memory was erected at

A bust in his memory was erected at

''The circumstance of Mr. Rogers having preached at Paul's cross, after Queen Mary arrived at the Tower, has been already stated. He confirmed in his sermon the true doctrine taught in King Edward's time, and exhorted the people to beware of the pestilence of popery, idolatry, and superstition. For this he was called to account, but so ably defended himself that, for that time, he was dismissed. The proclamation of the queen, however, to prohibit true preaching, gave his enemies a new handle against him. Hence he was again summoned before the council, and commanded to keep to his house. He did so, though he might have escaped; and though he perceived the state of the true religion to be desperate. He knew he could not want a living in Germany; and he could not forget a wife and ten children, and to seek means to succor them. But all these things were insufficient to induce him to depart, and, when once called to answer in Christ's cause, he stoutly defended it, and hazarded his life for that purpose.''

''After long imprisonment in his own house, the restless Bonner, bishop of London, caused him to be committed to Newgate, there to be lodged among thieves and murderers.''

''After Mr. Rogers had been long and straitly imprisoned, and lodged in Newgate among thieves, often examined, and very uncharitably entreated, and at length unjustly and most cruelly condemned by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, the fourth day of February, in the year of our Lord 1555, being Monday in the morning, he was suddenly warned by the keeper of Newgate's wife, to prepare himself for the fire; who, being then sound asleep, could scarce be awaked. At length being raised and awaked, and bid to make haste, then said he, "If it be so, I need not tie my points." And so was had down, first to bishop Bonner to be degraded: which being done, he craved of Bonner but one petition; and Bonner asked what that should be. Mr. Rogers replied that he might speak a few words with his wife before his burning, but that could not be obtained of him.''

''When the time came that he should be brought out of Newgate to Smithfield, the place of his execution, Mr. Woodroofe, one of the sheriffs, first came to Mr. Rogers, and asked him if he would revoke his abominable doctrine, and the evil opinion of the Sacrament of the altar. Mr. Rogers answered, "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Then Mr. Woodroofe said, "Thou art an heretic." "That shall be known," quoth Mr. Rogers, "at the Day of Judgment." "Well," said Mr. Woodroofe, "I will never pray for thee." "But I will pray for you," said Mr. Rogers; and so was brought the same day, the fourth of February, by the sheriffs, towards Smithfield, saying the Psalm Miserere by the way, all the people wonderfully rejoicing at his constancy; with great praises and thanks to God for the same. And there in the presence of Mr. Rochester, comptroller of the queen's household, Sir Richard Southwell, both the sheriffs, and a great number of people, he was burnt to ashes, washing his hands in the flame as he was burning. A little before his burning, his pardon was brought, if he would have recanted; but he utterly refused it. He was the first martyr of all the blessed company that suffered in Queen Mary's time that gave the first adventure upon the fire. His wife and children, being eleven in number, ten able to go, and one sucking at her breast, met him by the way, as he went towards Smithfield. This sorrowful sight of his own flesh and blood could nothing move him, but that he constantly and cheerfully took his death with wonderful patience, in the defence and quarrel of the Gospel of Christ."''

''The circumstance of Mr. Rogers having preached at Paul's cross, after Queen Mary arrived at the Tower, has been already stated. He confirmed in his sermon the true doctrine taught in King Edward's time, and exhorted the people to beware of the pestilence of popery, idolatry, and superstition. For this he was called to account, but so ably defended himself that, for that time, he was dismissed. The proclamation of the queen, however, to prohibit true preaching, gave his enemies a new handle against him. Hence he was again summoned before the council, and commanded to keep to his house. He did so, though he might have escaped; and though he perceived the state of the true religion to be desperate. He knew he could not want a living in Germany; and he could not forget a wife and ten children, and to seek means to succor them. But all these things were insufficient to induce him to depart, and, when once called to answer in Christ's cause, he stoutly defended it, and hazarded his life for that purpose.''

''After long imprisonment in his own house, the restless Bonner, bishop of London, caused him to be committed to Newgate, there to be lodged among thieves and murderers.''

''After Mr. Rogers had been long and straitly imprisoned, and lodged in Newgate among thieves, often examined, and very uncharitably entreated, and at length unjustly and most cruelly condemned by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, the fourth day of February, in the year of our Lord 1555, being Monday in the morning, he was suddenly warned by the keeper of Newgate's wife, to prepare himself for the fire; who, being then sound asleep, could scarce be awaked. At length being raised and awaked, and bid to make haste, then said he, "If it be so, I need not tie my points." And so was had down, first to bishop Bonner to be degraded: which being done, he craved of Bonner but one petition; and Bonner asked what that should be. Mr. Rogers replied that he might speak a few words with his wife before his burning, but that could not be obtained of him.''

''When the time came that he should be brought out of Newgate to Smithfield, the place of his execution, Mr. Woodroofe, one of the sheriffs, first came to Mr. Rogers, and asked him if he would revoke his abominable doctrine, and the evil opinion of the Sacrament of the altar. Mr. Rogers answered, "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Then Mr. Woodroofe said, "Thou art an heretic." "That shall be known," quoth Mr. Rogers, "at the Day of Judgment." "Well," said Mr. Woodroofe, "I will never pray for thee." "But I will pray for you," said Mr. Rogers; and so was brought the same day, the fourth of February, by the sheriffs, towards Smithfield, saying the Psalm Miserere by the way, all the people wonderfully rejoicing at his constancy; with great praises and thanks to God for the same. And there in the presence of Mr. Rochester, comptroller of the queen's household, Sir Richard Southwell, both the sheriffs, and a great number of people, he was burnt to ashes, washing his hands in the flame as he was burning. A little before his burning, his pardon was brought, if he would have recanted; but he utterly refused it. He was the first martyr of all the blessed company that suffered in Queen Mary's time that gave the first adventure upon the fire. His wife and children, being eleven in number, ten able to go, and one sucking at her breast, met him by the way, as he went towards Smithfield. This sorrowful sight of his own flesh and blood could nothing move him, but that he constantly and cheerfully took his death with wonderful patience, in the defence and quarrel of the Gospel of Christ."''

clergyman

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

translator and commentator. He guided the development of the Matthew Bible in vernacular English during the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and was the first English Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

executed as a heretic under Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

, who was determined to restore Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

Biography of John Rogers

Early life

Rogers was born inDeritend

Deritend is a historic area of Birmingham, England, built around a crossing point of the River Rea. It is first mentioned in 1276. Today Deritend is usually considered to be part of Digbeth.

History

Deritend was a crossing point of the River Rea ...

, an area of Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

then within the parish of Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, England. Located immediately to the north-east of Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a ward within the metropolitan authority. It is approximately 1.5 miles from Birmingham City Centre.

History

Aston wa ...

. His father was also called John Rogers and was a lorimer – a maker of bits and spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

s – whose family came from Aston; his mother was Margaret Wyatt, the daughter of a tanner with family in Erdington and Sutton Coldfield

Sutton Coldfield or the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, known locally as Sutton ( ), is a town and civil parish in the City of Birmingham, West Midlands, England. The town lies around 8 miles northeast of Birmingham city centre, 9 miles sou ...

.

Rogers was educated at the Guild School of St John the Baptist in Deritend, and at Pembroke Hall

Pembroke College (officially "The Master, Fellows and Scholars of the College or Hall of Valence-Mary") is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college is the third-oldest college of the university and has over 700 ...

, Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he graduated B.A. in 1526. Between 1532 and 1534 he was rector of Holy Trinity the Less in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

.

Antwerp and the ''Matthew Bible''

In 1534, Rogers went toAntwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

as chaplain to the English merchants of the Company of the Merchant Adventurers

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared g ...

.

Here he met

Here he met William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execu ...

, under whose influence he abandoned the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

faith, and married Antwerp native Adriana de Weyden (b. 1522, anglicised to Adrana Pratt in 1552) in 1537. After Tyndale's death, Rogers pushed on with his predecessor's English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

version of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, which he used as far as '' 2 Chronicles'', employing Myles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles (1488 – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the first ...

's translation (1535) for the remainder and for the ''Apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

''. Although it is claimed that Rogers was the first person to ever print a complete English Bible that was translated directly from the original Greek and Hebrew, there was also a reliance upon a Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible by Sebastian Münster and published in 1534/5.

Tyndale's New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Chris ...

had been published in 1526. The complete Bible was put out under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew in 1537; it was printed in Paris and Antwerp by Adriana's uncle, Sir Jacobus van Meteren. Richard Grafton published the sheets and got leave to sell the edition (1500 copies) in England. At the insistence of Archbishop Cranmer, the "King's most gracious license" was granted to this translation. Previously in the same year, the 1537 reprint of the Myles Coverdale's translation had been granted such a licence.

The pseudonym "Matthew" is associated with Rogers, but it seems more probable that Matthew stands for Tyndale's own name, which, back then, was dangerous to employ in England. Rogers had at least some involvement with the translation, although he most likely used large parts of the Tyndale and the Coverdale versions. Some historians declare Rogers "produced" the Matthew Bible. One source states that he "assembled" the Bible. Other sources suggest that his share in that work was probably confined to translating the prayer of Manasses (inserted here for the first time in a printed English Bible), the general task of editing the materials at his disposal, and preparing the marginal notes collected from various sources. These are often cited as the first original English language commentary on the Bible. Rogers also contributed the Song of Manasses in the Apocrypha, which he found in a French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Bible printed in 1535. His work was largely used by those who prepared the Great Bible

The Great Bible of 1539 was the first authorised edition of the Bible in English, authorised by King Henry VIII of England to be read aloud in the church services of the Church of England. The Great Bible was prepared by Myles Coverdale, worki ...

(1539–40), and this eventually led to the Bishops' Bible

The Bishops' Bible is an English translation of the Bible which was produced under the authority of the established Church of England in 1568. It was substantially revised in 1572, and the 1602 edition was prescribed as the base text for the ...

(1568) and the King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of K ...

.

Rogers matriculated at the University of Wittenberg

Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (german: Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), also referred to as MLU, is a public, research-oriented university in the cities of Halle and Wittenberg and the largest and oldest university i ...

on 25 November 1540, where he remained for three years, becoming a close friend of Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lut ...

and other leading figures of the early Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

. On leaving Wittenberg he spent four and a half years as a superintendent of a Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

church in Meldorf, Dithmarschen

Dithmarschen (, Low Saxon: ; archaic English: ''Ditmarsh''; da, Ditmarsken; la, label=Medieval Latin, Tedmarsgo) is a district in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is bounded by (from the north and clockwise) the districts of Nordfriesland, Sch ...

, near the mouth of the River Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Rep ...

in the north of Germany.

Rogers returned to England in 1548, where he published a translation of Philipp Melanchthon's ''Considerations of the Augsburg Interim''.

In 1550 he was presented to the crown livings of St Margaret Moses and St Sepulchre in London, and in 1551 was made a prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of th ...

of St. Paul's, where the dean and chapter soon appointed him divinity lecturer. He courageously denounced the greed shown by certain courtiers with reference to the property of the suppressed monasteries and defended himself before the privy council. He also declined to wear the prescribed vestments, donning instead a simple round cap. On the accession of Mary he preached at Paul's Cross commending the "true doctrine taught in King Edward's days," and warning his hearers against "pestilent Popery, idolatry and superstition." Defamatory pamphlets littered the streets exhorting Protestants to take up arms against Mary Tudor. ‘Nobles and gentlemen favouring the word of God’ were asked to overthrow the ‘detestable papists’, especially ‘the great devil’, Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was ...

, Bishop of Winchester. A number of leading Protestant figures, including John Rogers, were arrested and leading reformist bishops such as John Hooper and Hugh Latimer were imprisoned weeks later. Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Hen ...

was sent to the Tower for his role in Lady Jane's attempted coup.

Rogers was also against radical Protestants. After Joan of Kent

Joan, Countess of Kent (29 September 1326/1327 – 7 August 1385), known as The Fair Maid of Kent, was the mother of King Richard II of England, her son by her third husband, Edward the Black Prince, son and heir apparent of King Edward III. ...

was imprisoned in 1548 and convicted in April 1549, John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the s ...

, one of the few Protestants opposed to burnings, approached Rogers to intervene to save Joan, but he refused with the comment that burning was "sufficiently mild" for a crime as grave as heresy.

Imprisonment and martyrdom

On 16 August 1553 he was summoned before the council and bidden to keep within his own house. His emoluments were taken away and his

On 16 August 1553 he was summoned before the council and bidden to keep within his own house. His emoluments were taken away and his prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of t ...

was filled in October. In January 1554, Bonner, the new Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, sent him to Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

, where he lay with John Hooper, Laurence Saunders, John Bradford and others for a year. Their petitions, whether for less rigorous treatment or for opportunity of stating their case, were disregarded. In December 1554, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

re-enacted the penal statutes against Lollards, and on 22 January 1555, two days after they took effect, Rogers (with ten other people) came before the council at Gardiner's house in Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, and defended himself in the examination that took place. On 28 and 29 January he came before the commission appointed by Cardinal Pole

Reginald Pole (12 March 1500 – 17 November 1558) was an English cardinal of the Catholic Church and the last Catholic archbishop of Canterbury, holding the office from 1556 to 1558, during the Counter-Reformation.

Early life

Pole was born a ...

, and was sentenced to death by Gardiner for heretically denying the Christian character of the Church of Rome and the real presence in the sacrament. He awaited and met death cheerfully, though he was even denied a meeting with his wife. Shortly before the execution, Rogers was offered a pardon if he were to recant but refused.

He was burned at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

on 4 February 1555 at Smithfield. Bishop Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Hen ...

who had encouraged the Matthew Bible, was executed in 1556 also by Queen Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She ...

.

Antoine de Noailles

Antoine, 1st comte de Noailles (4 September 150411 March 1563) became admiral of France, and was ambassador in England for three years, 1553–1556, maintaining a gallant but unsuccessful rivalry with the Spanish ambassador, Simon Renard.

Antoi ...

, the French ambassador, said in a letter that Rogers' death confirmed the alliance between the Pope and England. He also spoke of the support given to Rogers by the greatest part of the people: "even his children assisted at it, comforting him in such a manner that it seemed as if he had been led to a wedding."

A bust in his memory was erected at

A bust in his memory was erected at St John's Church, Deritend

St John's Church, Deritend was a parish church in the Church of England in Birmingham, which stood from 1735 until it was demolished in 1947.

History

A church was established in 1380 when the villagers in Deritend were given the right to build ...

in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the We ...

in 1853, by public subscription; the church was demolished in 1947.

John Rogers, Vicar of St. Sepulchre's, and Reader of St. Paul's, London

The quotation that follows is from ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engli ...

'', Chapter 16. It is included here because of its historical significance, being the vehicle by which the story of Rev. John Rogers has been most widely disseminated.

''"John Rogers was educated at Cambridge, and was afterward many years chaplain to the merchant adventurers at Antwerp in Brabant. Here he met with the celebrated martyr William Tyndale, and Miles Coverdale, both voluntary exiles from their country for their aversion to popish superstition and idolatry. They were the instruments of his conversion; and he united with them in that translation of the Bible into English, entitled "The Translation of Thomas Matthew." From the Scriptures he knew that unlawful vows may be lawfully broken; hence he married, and removed to Wittenberg in Saxony, for the improvement of learning; and he there learned the Dutch language, and received the charge of a congregation, which he faithfully executed for many years. On King Edward's accession, he left Saxony to promote the work of reformation in England; and, after some time, Nicholas Ridley, then bishop of London, gave him a prebend in St. Paul's Cathedral, and the dean and chapter appointed him reader of the divinity lesson there. Here he continued until Queen Mary's succession to the throne, when the Gospel and true religion were banished, and the Antichrist of Rome, with his superstition and idolatry, introduced.''

''The circumstance of Mr. Rogers having preached at Paul's cross, after Queen Mary arrived at the Tower, has been already stated. He confirmed in his sermon the true doctrine taught in King Edward's time, and exhorted the people to beware of the pestilence of popery, idolatry, and superstition. For this he was called to account, but so ably defended himself that, for that time, he was dismissed. The proclamation of the queen, however, to prohibit true preaching, gave his enemies a new handle against him. Hence he was again summoned before the council, and commanded to keep to his house. He did so, though he might have escaped; and though he perceived the state of the true religion to be desperate. He knew he could not want a living in Germany; and he could not forget a wife and ten children, and to seek means to succor them. But all these things were insufficient to induce him to depart, and, when once called to answer in Christ's cause, he stoutly defended it, and hazarded his life for that purpose.''

''After long imprisonment in his own house, the restless Bonner, bishop of London, caused him to be committed to Newgate, there to be lodged among thieves and murderers.''

''After Mr. Rogers had been long and straitly imprisoned, and lodged in Newgate among thieves, often examined, and very uncharitably entreated, and at length unjustly and most cruelly condemned by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, the fourth day of February, in the year of our Lord 1555, being Monday in the morning, he was suddenly warned by the keeper of Newgate's wife, to prepare himself for the fire; who, being then sound asleep, could scarce be awaked. At length being raised and awaked, and bid to make haste, then said he, "If it be so, I need not tie my points." And so was had down, first to bishop Bonner to be degraded: which being done, he craved of Bonner but one petition; and Bonner asked what that should be. Mr. Rogers replied that he might speak a few words with his wife before his burning, but that could not be obtained of him.''

''When the time came that he should be brought out of Newgate to Smithfield, the place of his execution, Mr. Woodroofe, one of the sheriffs, first came to Mr. Rogers, and asked him if he would revoke his abominable doctrine, and the evil opinion of the Sacrament of the altar. Mr. Rogers answered, "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Then Mr. Woodroofe said, "Thou art an heretic." "That shall be known," quoth Mr. Rogers, "at the Day of Judgment." "Well," said Mr. Woodroofe, "I will never pray for thee." "But I will pray for you," said Mr. Rogers; and so was brought the same day, the fourth of February, by the sheriffs, towards Smithfield, saying the Psalm Miserere by the way, all the people wonderfully rejoicing at his constancy; with great praises and thanks to God for the same. And there in the presence of Mr. Rochester, comptroller of the queen's household, Sir Richard Southwell, both the sheriffs, and a great number of people, he was burnt to ashes, washing his hands in the flame as he was burning. A little before his burning, his pardon was brought, if he would have recanted; but he utterly refused it. He was the first martyr of all the blessed company that suffered in Queen Mary's time that gave the first adventure upon the fire. His wife and children, being eleven in number, ten able to go, and one sucking at her breast, met him by the way, as he went towards Smithfield. This sorrowful sight of his own flesh and blood could nothing move him, but that he constantly and cheerfully took his death with wonderful patience, in the defence and quarrel of the Gospel of Christ."''

''The circumstance of Mr. Rogers having preached at Paul's cross, after Queen Mary arrived at the Tower, has been already stated. He confirmed in his sermon the true doctrine taught in King Edward's time, and exhorted the people to beware of the pestilence of popery, idolatry, and superstition. For this he was called to account, but so ably defended himself that, for that time, he was dismissed. The proclamation of the queen, however, to prohibit true preaching, gave his enemies a new handle against him. Hence he was again summoned before the council, and commanded to keep to his house. He did so, though he might have escaped; and though he perceived the state of the true religion to be desperate. He knew he could not want a living in Germany; and he could not forget a wife and ten children, and to seek means to succor them. But all these things were insufficient to induce him to depart, and, when once called to answer in Christ's cause, he stoutly defended it, and hazarded his life for that purpose.''

''After long imprisonment in his own house, the restless Bonner, bishop of London, caused him to be committed to Newgate, there to be lodged among thieves and murderers.''

''After Mr. Rogers had been long and straitly imprisoned, and lodged in Newgate among thieves, often examined, and very uncharitably entreated, and at length unjustly and most cruelly condemned by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester, the fourth day of February, in the year of our Lord 1555, being Monday in the morning, he was suddenly warned by the keeper of Newgate's wife, to prepare himself for the fire; who, being then sound asleep, could scarce be awaked. At length being raised and awaked, and bid to make haste, then said he, "If it be so, I need not tie my points." And so was had down, first to bishop Bonner to be degraded: which being done, he craved of Bonner but one petition; and Bonner asked what that should be. Mr. Rogers replied that he might speak a few words with his wife before his burning, but that could not be obtained of him.''

''When the time came that he should be brought out of Newgate to Smithfield, the place of his execution, Mr. Woodroofe, one of the sheriffs, first came to Mr. Rogers, and asked him if he would revoke his abominable doctrine, and the evil opinion of the Sacrament of the altar. Mr. Rogers answered, "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Then Mr. Woodroofe said, "Thou art an heretic." "That shall be known," quoth Mr. Rogers, "at the Day of Judgment." "Well," said Mr. Woodroofe, "I will never pray for thee." "But I will pray for you," said Mr. Rogers; and so was brought the same day, the fourth of February, by the sheriffs, towards Smithfield, saying the Psalm Miserere by the way, all the people wonderfully rejoicing at his constancy; with great praises and thanks to God for the same. And there in the presence of Mr. Rochester, comptroller of the queen's household, Sir Richard Southwell, both the sheriffs, and a great number of people, he was burnt to ashes, washing his hands in the flame as he was burning. A little before his burning, his pardon was brought, if he would have recanted; but he utterly refused it. He was the first martyr of all the blessed company that suffered in Queen Mary's time that gave the first adventure upon the fire. His wife and children, being eleven in number, ten able to go, and one sucking at her breast, met him by the way, as he went towards Smithfield. This sorrowful sight of his own flesh and blood could nothing move him, but that he constantly and cheerfully took his death with wonderful patience, in the defence and quarrel of the Gospel of Christ."''

Notes

References

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rogers, John Alumni of Pembroke College, Cambridge Translators of the Bible into English People executed for heresy Executed British people People executed under Mary I of England 1500s births 1555 deaths Executed English people 16th-century Protestant martyrs People executed by the Kingdom of England by burning People from Birmingham, West Midlands Protestant martyrs of England