John Rae (explorer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Rae ( iu, ᐊᒡᓘᑲ, i=no, ; 30 September 1813 – 22 July 1893) was a Scottish surgeon who explored parts of

From 1836 to 1839, the Scottish explorer and fur trader Thomas Simpson sailed along much of the northern coast of Canada. His cousin Sir George Simpson proposed to link the furthest-east point Thomas Simpson had reached by sending an overland expedition from Hudson Bay. Rae was chosen because of his well-known skill in overland travel, but he first had to travel to the

From 1836 to 1839, the Scottish explorer and fur trader Thomas Simpson sailed along much of the northern coast of Canada. His cousin Sir George Simpson proposed to link the furthest-east point Thomas Simpson had reached by sending an overland expedition from Hudson Bay. Rae was chosen because of his well-known skill in overland travel, but he first had to travel to the

With the prize money awarded for finding evidence of the fate of Franklin's expedition, Rae commissioned the construction of a ship intended for polar exploration, the ''Iceberg''. The ship was built at Kingston,

With the prize money awarded for finding evidence of the fate of Franklin's expedition, Rae commissioned the construction of a ship intended for polar exploration, the ''Iceberg''. The ship was built at Kingston,

John Rae died from an

John Rae died from an John Rae Society

/ref> was formed in Orkney to promote Rae's achievements.

1985. * Newman, Peter C

Caesars of the Wilderness

1987. * Berton, Pierre

The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909

Random House of Canada, 2001. * Greenford, Miles

In John Rae's Company

*

northern Canada

Northern Canada, colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories an ...

.

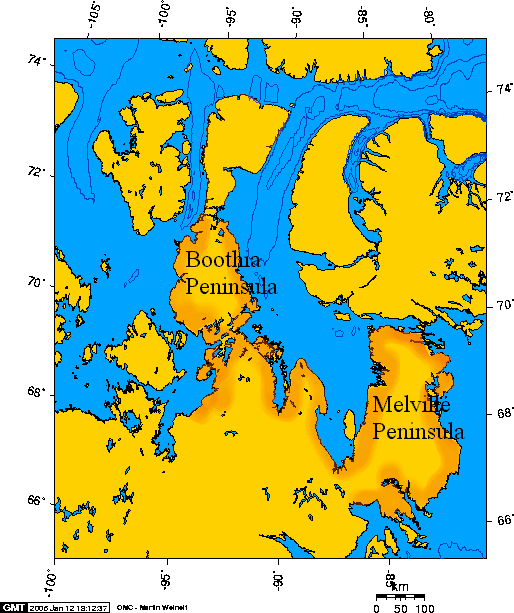

Rae explored the Gulf of Boothia, northwest of the Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

, from 1846 to 1847, and the Arctic coast near Victoria Island

Victoria Island ( ikt, Kitlineq, italic=yes) is a large island in the Arctic Archipelago that straddles the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada. It is the eighth-largest island in the world, and at in area, it is ...

from 1848 to 1851. In 1854, back in the Gulf of Boothia, he obtained credible information from local Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

peoples about the fate of the Franklin Expedition, which had disappeared in the area in 1848. Rae was noted for his physical stamina, skill at hunting, boat handling, use of native methods, and ability to travel long distances with little equipment while living off the land.

Early life

Rae was born at the Hall of Clestrain inOrkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

in the north of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

with family ties to Clan MacRae. After studying medicine in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, he graduated with a degree from the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 1 ...

and was licensed by the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) is a professional organisation of surgeons. The College has seven active faculties, covering a broad spectrum of surgical, dental, and other medical practices. Its main campus is located o ...

.

He went to work for the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business di ...

as a surgeon, accepting a post at Moose Factory

Moose Factory is a community in the Cochrane District, Ontario, Canada. It is located on Moose Factory Island, near the mouth of the Moose River, which is at the southern end of James Bay. It was the first English-speaking settlement in lands no ...

, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

, where he remained for ten years. While working for the company, treating both European and indigenous employees, Rae became known for his prodigious stamina and skilled use of snowshoes. He learned to live off the land like a native and, working with the local craftsmen, designed his own snowshoes. This knowledge allowed him to travel great distances with little equipment and few followers, unlike many other explorers of the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

.

Explorations

Gulf of Boothia

Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hudson's Bay ...

to learn the art of surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

. On , Rae left Moose Factory

Moose Factory is a community in the Cochrane District, Ontario, Canada. It is located on Moose Factory Island, near the mouth of the Moose River, which is at the southern end of James Bay. It was the first English-speaking settlement in lands no ...

, went up the Missinaibi River, and took the usual voyageur route west.

When he reached the Red River Colony on 9 October, he found his instructor seriously ill. After the man died, Rae headed for Sault Ste. Marie in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

to find another instructor. The two-month, winter journey was by dog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing. Traditionally in Greenland and th ...

along the north shore of Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

. From there, Sir George told him to go to Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

to study under John Henry Lefroy at the Toronto Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory

The Toronto Magnetic and Meteorological Observatory is a historical observatory located on the grounds of the University of Toronto, in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The original building was constructed in 1840 as part of a worldwide research project ...

. Returning from Toronto, he received final instructions at Sault Ste. Marie.

Rae finally departed on the voyage to Simpson's furthest-east on 5 August 1845, taking the usual voyageur route via Lake Winnipeg

Lake Winnipeg (french: Lac Winnipeg, oj, ᐑᓂᐸᑲᒥᐠᓴᑯ˙ᑯᐣ, italics=no, Weenipagamiksaguygun) is a very large, relatively shallow lake in North America, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. Its southern end is about north of ...

and reaching York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) located on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill. ...

on 8 October, where he wintered. On 12 June 1846, he headed north in two boats and reached Repulse Bay

Repulse Bay or Tsin Shui Wan is a bay in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, located in the Southern District, Hong Kong. It is one of the most expensive residential areas in the world.

Geography

Repulse Bay is located in the southern ...

at the south end of the Melville Peninsula in July. The local Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

told him that there was salt water to the northwest, so he chose this as his base. On his first journey, which began on 26 July, he dragged one of his boats northwest to Committee Bay in the south of the Gulf of Boothia. Here he learned from the Inuit that the Gulf of Boothia was a bay and that he would have to cross land to reach Simpson's furthest-east.

In 1830, John Ross had also been told that the Gulf of Boothia was a bay. He sailed partway up the east coast of the Gulf, but has soon turned back because he needed to make preparations for winter. He became one of the first Europeans to winter in the high Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

without the aid of a depot ship. By December he had learned how to build igloo

An igloo (Inuit languages: , Inuktitut syllabics (plural: )), also known as a snow house or snow hut, is a type of shelter built of suitable snow.

Although igloos are often associated with all Inuit, they were traditionally used only b ...

s, which he later found warmer than European tents.

Rae's second journey began on 5 April 1847. He crossed to Committee Bay, travelled up its west coast for four days and then headed west across the base of the Simpson Peninsula to Pelly Bay. He went north and from a hill thought he could see Lord Mayor Bay, on the west side of the Gulf of Boothia, where John Ross had been trapped in ice from 1829 to 1833. He circled much of the coast of the Simpson Peninsula and returned to Repulse Bay. His third journey began on 13 May 1847. He crossed from Repulse Bay to Committee Bay and went up the east coast hoping to reach the Fury and Hecla Strait, which William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry (19 December 1790 – 8 July 1855) was an Royal Navy officer and explorer best known for his 1819–1820 expedition through the Parry Channel, probably the most successful in the long quest for the Northwest Pas ...

's men had seen in 1822. The weather was bad and they began to run short of food. On 28 May, Rae turned back at a place he called Cape Crozier which he thought was about south of the strait.

He left Repulse Bay on 12 August, when the ice broke up, and reached York Factory on 6 September 1847. He soon left for England and Scotland. Although he had not reached Simpson's furthest-east, he had reduced the gap to less than .

Arctic coast

From 1848 to 1851, Rae made three journeys along the Arctic coast. The first took him from the Mackenzie River to theCoppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave and Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake, and flows generally north to Coronation Gul ...

, which had been done before. On the second he tried to cross to Victoria Island

Victoria Island ( ikt, Kitlineq, italic=yes) is a large island in the Arctic Archipelago that straddles the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada. It is the eighth-largest island in the world, and at in area, it is ...

but was blocked by ice. On the third he explored the whole south coast of Victoria Island.

By 1848, it was clear that Sir John Franklin's expedition, which had traveled west from the coast of Greenland in 1845, had been lost in the Arctic. Three expeditions were sent to find him: one from the east, one through the Bering Strait, and one overland to the Arctic coast, this last led by Sir John Richardson. Most of the Arctic coast had been traced a decade earlier by Thomas Simpson. North of the coast were two coastlines called Wollaston Land and Victoria Land (Victoria Island). Franklin's crew was thought to be somewhere in the unexplored area north of that. The 61-year-old Richardson chose Rae as his second-in-command.

First journey

The Rae–Richardson Arctic Expedition leftLiverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

in March 1848, reached New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and took the usual voyageur routes west from Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

. On 15 July 1848, the expedition reached Fort Resolution on Great Slave Lake. John Bell was sent downriver to establish winter quarters at Fort Confidence on the east arm of Great Bear Lake. Richardson and Rae traveled down the Mackenzie River and turned east along the coast.

They hoped to cross north to Wollaston Land, as southern Victoria Island was then known, but ice conditions made this impossible. Through worsening ice, they rounded Cape Krusenstern at the west end of Coronation Gulf

Coronation Gulf lies between Victoria Island and mainland Nunavut in Canada. To the northwest it connects with Dolphin and Union Strait and thence the Beaufort Sea and Arctic Ocean; to the northeast it connects with Dease Strait and thence Queen ...

(not Cape Krusenstern

Cape Krusenstern is a cape on the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, located near the village of Kivalina at .

It is bounded by Kotzebue Sound to the south and the Chukchi Sea to the west, and consists of a series of beach ridges ...

in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

), and turned south. By the first of September it was clear that they had run out of time, so they abandoned their boats and headed overland. They crossed the Rae River

The Rae River (Pallirk) is a waterway that flows from Akuliakattak Lake into Richardson Bay, Coronation Gulf. Its mouth is situated northwest of Kugluktuk, Nunavut. Its shores were the ancestral home of Copper Inuit subgroups: the Kanianermiut (a ...

and Richardson River and on 15 September reached their winter quarters at Fort Confidence at the northeast end of Great Bear Lake.

Second journey

In December and January, Rae made two trips northeast to find a better route to Coronation Gulf. On 7 May, Richardson and Bell left with most of the men. Rae left on 9 June with seven men. Hauling a boat overland they reached the Kendall River on 21 June. The next day they reached theCoppermine River

The Coppermine River is a river in the North Slave and Kitikmeot regions of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut in Canada. It is long. It rises in Lac de Gras, a small lake near Great Slave Lake, and flows generally north to Coronation Gul ...

and waited a week for the ice to break up. They descended the Coppermine and waited again for the ice to clear on Coronation Gulf.

It was 30 July before they reached Cape Krusenstern on Coronation Gulf. From here they hoped to cross the Dolphin and Union Strait

Dolphin and Union Strait lies in both the Northwest Territories ( Inuvik Region) and Nunavut ( Kitikmeot Region), Canada, between the mainland and Victoria Island. It is part of the Northwest Passage. It links Amundsen Gulf, lying to the northwe ...

to Wollaston Land. On 19 August, they made the attempt, but after they were caught in fog and moving ice and spent three hours rowing back to their starting point. Rae waited as long as he could and turned back, reaching Fort Confidence on the first of September. On the return journey their boat was lost at Bloody Falls and Albert One-Eye, the Inuk interpreter, was killed.

Third journey

They reached Fort Simpson to the west ofYellowknife

Yellowknife (; Dogrib: ) is the capital, largest community, and only city in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, about south of the Arctic Circle, on the west side of Yellowknife Bay near the ...

in late September. A week later William Pullen showed up, having sailed east from the Bering Strait and up the Mackenzie River. In June 1850, Rae and Pullen went east up the Mackenzie with that year's furs. On 25 June, just short of Great Slave Lake, he was met by an express canoe. Pullen was promoted to captain and told to go north and try again. Rae received three letters from Sir George Simpson, Francis Beaufort

Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort (; 27 May 1774 – 17 December 1857) was an Irish hydrographer, rear admiral of the Royal Navy, and creator of the Beaufort cipher and the Beaufort scale.

Early life

Francis Beaufort was descende ...

, and Lady Jane Franklin all telling him to return to the Arctic. Simpson promised supplies and left the route to Rae's discretion. Pullen left immediately with most of the equipment.

Rae escorted the furs as far as Methye Portage and returned to Fort Simpson in August. En route he wrote Sir George a letter outlining his complex but ultimately successful plan. That winter he would go to Fort Confidence and build two boats and collect supplies. Next spring he would use dog sleds to cross to Wollaston Land and go as far as he could before the ice melt made it impossible to recross the Strait. Meanwhile, his men would have hauled the boats overland to Coronation Gulf. When the ice melted he would follow the coast by boat as long as there was open water. He reached Fort Confidence in September and spent the winter there.

On 25 April 1851, he left the fort. On 2 May he crossed the frozen strait via Douglas Island to Lady Franklin Point

Lady Franklin Point is a landform in the Canadian Arctic territory of Nunavut. It is located on southwestern Victoria Island in the Coronation Gulf by Austin Bay at the eastern entrance of Dolphin and Union Strait.

The Point is uninhabited b ...

, the southwestern-most point on Victoria Island. Heading east he passed and named the Richardson Islands and passed what he thought was the westernmost point reached by Thomas Simpson on his return journey in 1839. Heading west he passed Lady Franklin Point and followed the coast north and west around Simpson Bay, which he named. The coast swung north but it was getting late.

He made a final push, the coast swung to the northeast and on 24 May, he could look north across Prince Albert Sound. Unknown to Rae, just 10 days earlier, a sledge party from Robert McClure's expedition had been on the north side of the sound. He turned south, crossed Dolphin and Union Strait safely and on 5 June turned inland. The journey to camp on the Kendall River was the least pleasant part of the journey since he had to travel over melting snow and through meltwater.

On 15 June 1851, two days after the boat arrived, he set off down the Kendall River and Coppermine River with 10 men. He waited several times for the ice to clear and in early July he started east along the south coast of Coronation Gulf. In late July he crossed the mouth of Bathurst Inlet

Bathurst Inlet, officially Kiluhiqtuq, is a deep inlet located along the northern coast of the Canadian mainland, at the east end of Coronation Gulf, into which the Burnside and Western rivers empty. The name, or its native equivalent ''Kingo ...

and reached Cape Flinders Cape Flinders is a headland in the northern Canadian territory of Nunavut. It is located on the western point of the Kent Peninsula, now known as Kiillinnguyaq.

The cape was named by Sir John Franklin in 1821 after the navigator Matthew Flinders ...

at the western end of the Kent Peninsula. He reached Cape Alexander at its east end on 24 July, and on 27 July crossed the strait to Victoria Island. He explored Cambridge Bay

Cambridge Bay (Inuinnaqtun: ''Iqaluktuuttiaq'' Inuktitut: ᐃᖃᓗᒃᑑᑦᑎᐊᖅ; 2021 population 1,760; population centre 1,403) is a hamlet located on Victoria Island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is the largest settle ...

which he found to be a better harbour than Dease and Simpson had reported.

He left the bay and went east along an unknown coast. The coast swung north and the weather got worse. By August he was in Albert Edward Bay. Blocked by ice, he went north on foot and reached his furthest on 13 August. Returning, he left a cairn which was found by Richard Collinson's men two years later. He then made three unsuccessful attempts to cross Victoria Strait east to King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the 6 ...

. Victoria Strait is nearly always impassable. On 21 August, he found two pieces of wood that had clearly come from a European ship. These were probably from Franklin's ship, but Rae chose not to guess.

On 29 August, he reached Lady Franklin Point and crossed to the mainland. He worked his way up the swollen Coppermine and reached Fort Confidence on 10 September. He had traveled on land, by boat, charted of unknown coast, followed the whole south coast of Victoria Island, and proved that Wollaston Land and Victoria Land were part of the same island, but had not found Franklin.

By 1849, Rae was in charge of the Mackenzie River district at Fort Simpson. While exploring the Boothia Peninsula in 1854, Rae made contact with local Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

, from whom he obtained much information about the fate of the Franklin expedition. His report to the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

carried shocking and unwelcome evidence that cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b ...

had been a last resort for some of the survivors. When it was leaked to the press, Franklin's widow Lady Jane Franklin was outraged and recruited many important supporters, among them Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

, who wrote several pamphlets condemning Rae for daring to suggest Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

sailors would have resorted to cannibalism. In return, Dickens argued – from analogy – that the Inuit, whom he viewed very negatively, as evidenced by his writings, are more likely to have killed the expedition's survivors.

Franklin's fate

Rae headed south toFort Chipewyan

Fort Chipewyan , commonly referred to as Fort Chip, is a hamlet in northern Alberta, Canada, within the Regional Municipality (RM) of Wood Buffalo. It is located on the western tip of Lake Athabasca, adjacent to Wood Buffalo National Park, app ...

in Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest T ...

, waited for a hard freeze, travelled by snowshoe to Fort Garry in Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

, took the Crow Wing Trail

The Red River Trails were a network of ox cart routes connecting the Red River Colony (the "Selkirk Settlement") and Fort Garry in British North America with the head of navigation on the Mississippi River in the United States. These trade route ...

to Saint Paul, Minnesota

Saint Paul (abbreviated St. Paul) is the capital of the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Ramsey County. Situated on high bluffs overlooking a bend in the Mississippi River, Saint Paul is a regional business hub and the center ...

, and then travelled to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, then Hamilton, Ontario

Hamilton is a port city in the Canadian province of Ontario. Hamilton has a population of 569,353, and its census metropolitan area, which includes Burlington and Grimsby, has a population of 785,184. The city is approximately southwest of ...

, New York, and London, which he reached in late March 1852. In England he proposed to return to Boothia and complete his attempt to link Hudson Bay to the Arctic coast by dragging a boat to the Back River. He went to New York, Montreal, and then Sault Ste. Marie by steamer, Fort William by canoe, and reached York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) located on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill. ...

on 18 June 1853, where he picked up his two boats.

He left on 24 June and reached Chesterfield Inlet on 17 July. Finding a previously unknown river, he followed it for before it became too small to use. Judging that it was too late to drag the boat north to the Back River, he turned back and wintered at his old camp on Repulse Bay

Repulse Bay or Tsin Shui Wan is a bay in the southern part of Hong Kong Island, located in the Southern District, Hong Kong. It is one of the most expensive residential areas in the world.

Geography

Repulse Bay is located in the southern ...

. He left Repulse Bay on 31 March 1854. Near Pelly Bay he met some Inuit, one of whom had a gold cap-band. Asked where he got it, he replied that it came from a place 10 to 12 days away where 35 or so ''kabloonat'' had starved to death. Rae bought the cap-band and said he would buy anything similar.

On 27 April, he reached frozen salt-water south of what is now called Rae Strait

Rae Strait is a small strait in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula on the mainland to the east. It is named after Scottish Arctic explorer John Rae who, in 1854, was the fir ...

. A few miles west, on the south side of the bay, he reached what he believed was the Castor and Pollux River

Castor most commonly refers to:

*Castor (star), a star in the Gemini constellation

*Castor, one of the Dioscuri/Gemini twins Castor and Pollux in Greco-Roman mythology

Castor or CASTOR may also refer to:

Science and technology

*Castor (rocket s ...

, which Simpson had reached from the west in 1839. He then turned north along the western portion of the Boothia Peninsula, the last uncharted coast of North America, hoping to reach Bellot Strait

Bellot Strait is a strait in Nunavut that separates Somerset Island to its north from the Murchison Promontory of Boothia Peninsula to its south, which is the northernmost part of the mainland of the Americas. The and strait connects the Gulf ...

and so close the last gap in the line from Bering Strait to Hudson Bay. The coast continued north instead of swinging west to form the south shore of King William Land.

On 6 May, he reached his furthest north, which he named Point de la Guiche after an obscure French traveller he had met in New York. It appeared that King William Land was an island and the coast to the north was the same as had been seen by James Clark Ross in 1831. Author Ken McGoogan

Kenneth McGoogan (born 1947). is the Canadian author of fifteen books, including ''Flight of the Highlanders'', ''Dead Reckoning'', ''50 Canadians Who Changed the World'', ''How the Scots Invented Canada'', and four biographical narratives focusing ...

has claimed that Rae here effectively discovered the final link in the Northwest Passage as followed in the following century by Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

, although Arctic historian William Barr

William Pelham Barr (born May 23, 1950) is an American attorney who served as the 77th and 85th United States attorney general in the administrations of Presidents George H. W. Bush and Donald Trump.

Born and raised in New York City, Barr ...

has refuted that claim, citing the uncharted between Ross's discoveries and the Bellot Strait.

With only two men fit for heavy travel, Rae turned back. Reaching Repulse Bay on 26 May, he found several Inuit families who had come to trade relics. They said that four winters ago some other Inuit had met at least 40 ''kabloonat'' who were dragging a boat south. Their leader was a tall, stout man with a telescope, thought to be Francis Crozier, Franklin's second-in-command. They communicated by gestures that their ships had been crushed by ice and that they were going south to hunt deer. When the Inuit returned the following spring they found about 30 corpses and signs of cannibalism. One of the artefacts Rae bought was a small silver plate. Engraved on the back was "Sir John Franklin, K.C.H". With this important information, Rae chose not to continue exploring. He left Repulse Bay on 4 August 1854, as soon as the ice cleared.

Later career

With the prize money awarded for finding evidence of the fate of Franklin's expedition, Rae commissioned the construction of a ship intended for polar exploration, the ''Iceberg''. The ship was built at Kingston,

With the prize money awarded for finding evidence of the fate of Franklin's expedition, Rae commissioned the construction of a ship intended for polar exploration, the ''Iceberg''. The ship was built at Kingston, Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the ...

. Rae moved to Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilto ...

, Canada West, also on Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

, in 1857, where his two brothers lived and operated a shipping firm on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

.

The ''Iceberg'' was launched in 1857. Rae intended to sail her to England the following year to be outfitted for polar voyages. In the meantime, she was put to use as a cargo ship. Tragically she was lost with all seven men on board in 1857, on her first commercial trip, hauling coal from Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S ...

, to Kingston. The wreck, somewhere in Lake Ontario, has never been located. While in Hamilton, Rae became a founding member of the Hamilton Scientific Association, which became the Hamilton Association for the Advancement of Literature, Science and Art, one of Canada's oldest scientific and cultural organizations.

In 1860, Rae worked on the telegraph line to America, visiting Iceland and Greenland. In 1864, he made a further telegraph survey in the west of Canada. In 1884, at age 71, he was again working for the Hudson's Bay Company, this time as an explorer of the Red River for a proposed telegraph line from the United States to Russia.

Death and legacy

John Rae died from an

John Rae died from an aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also be a nidus ( ...

in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Garden ...

on 22 July 1893. A week later his body arrived in Orkney. He was buried at St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall.

A memorial to Rae, lying as in sleep upon the ground, is inside the cathedral. The memorial by North Ronaldsay

North Ronaldsay (, also , sco, North Ronalshee) is the northernmost island in the Orkney archipelago of Scotland. With an area of , it is the fourteenth-largest.Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 334 It is mentioned in the '' Orkneyinga saga''; in moder ...

sculptor Ian Scott, unveiled at Stromness

Stromness (, non, Straumnes; nrn, Stromnes) is the second-most populous town in Orkney, Scotland. It is in the southwestern part of Mainland Orkney. It is a burgh with a parish around the outside with the town of Stromness as its capital.

E ...

pierhead in 2013, is a statue of Rae with an inscription describing him as "the discoverer of the final link in the first navigable Northwest Passage." Rae Strait

Rae Strait is a small strait in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula on the mainland to the east. It is named after Scottish Arctic explorer John Rae who, in 1854, was the fir ...

, Rae Isthmus, Rae River

The Rae River (Pallirk) is a waterway that flows from Akuliakattak Lake into Richardson Bay, Coronation Gulf. Its mouth is situated northwest of Kugluktuk, Nunavut. Its shores were the ancestral home of Copper Inuit subgroups: the Kanianermiut (a ...

, Mount Rae

Mount Rae is a mountain located on the east side of Highway 40 between Elbow Pass and the Ptarmigan Cirque in the Canadian Rockies of Alberta. Mount Rae was named after John Rae, explorer of Northern Canada, in 1859.

Due to its relatively hig ...

, Point Rae, and Rae-Edzo were all named for him.

The outcome of Lady Franklin's efforts to glorify the dead of the Franklin expedition meant that Rae, who had discovered evidence suggesting a much less noble fate, was shunned somewhat by the British establishment. Although he found the first clue to the fate of Franklin, Rae was never awarded a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

, nor was he remembered at the time of his death, dying quietly in London. In comparison, fellow Scot and contemporary explorer David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

was buried with full imperial honours in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Historians have since studied Rae's expeditions and his roles in finding the Northwest Passage and learning the fate of Franklin's crew. Authors such as Ken McGoogan

Kenneth McGoogan (born 1947). is the Canadian author of fifteen books, including ''Flight of the Highlanders'', ''Dead Reckoning'', ''50 Canadians Who Changed the World'', ''How the Scots Invented Canada'', and four biographical narratives focusing ...

have noted Rae was willing to adopt and learn the ways of indigenous Arctic peoples, which made him stand out as the foremost specialist of his time in cold-climate survival and travel. Rae also respected Inuit customs, traditions, and skills, which went against the beliefs of many 19th-century Europeans that most native peoples were too primitive to offer anything of educational value.

In July 2004, Orkney and Shetland MP Alistair Carmichael introduced into the UK Parliament a motion proposing, ''inter alia'', that the House "regrets that Dr Rae was never awarded the public recognition that was his due". In March 2009, he introduced a further motion urging Parliament to formally state it "regrets that memorials to Sir John Franklin outside the Admiralty headquarters and inside Westminster Abbey still inaccurately describe Franklin as the first to discover the orth Westpassage, and calls on the Ministry of Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in state ...

and the Abbey authorities to take the necessary steps to clarify the true position." In October 2014, a plaque dedicated to Rae was installed at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Rae is depicted in the 2008 movie ''Passage'' from the National Film Board of Canada

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB; french: Office national du film du Canada (ONF)) is Canada's public film and digital media producer and distributor. An agency of the Government of Canada, the NFB produces and distributes documentary fi ...

.

In June 2011, a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term ...

was installed by English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

on the house where John Rae spent the last years of his life, No. 4 Lower Addison Gardens, in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Garden ...

, west London. After a conference in September 2013 in Stromness, Orkney to celebrate the 200th anniversary of John Rae's birth, a statue was erected to Rae at the pierhead. In December 2013, The John Rae Society/ref> was formed in Orkney to promote Rae's achievements.

Footnotes

Bibliography

* McGoogan, Ken. ''Fatal Passage : The Story of John Rae – the Arctic hero time forgot.'' New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002. * Richards, Robert L. ''Dr. John Rae.'' Whitby, North Yorkshire: Caedmon of Whitby Publishers, c.1985. * * Nadolny, Sten. Die Entdeckung der Langsamkeit. 1983. * Newman, Peter C.br> Company of Adventurers1985. * Newman, Peter C

Caesars of the Wilderness

1987. * Berton, Pierre

The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909

Random House of Canada, 2001. * Greenford, Miles

In John Rae's Company

*

External links

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rae, John 19th-century explorers 19th-century Scottish medical doctors 1813 births 1893 deaths Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Explorers of Canada Explorers of the Arctic Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society Fellows of the Royal Society Hudson's Bay Company people People from Orkney Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Scottish polar explorers Scottish surgeons