John McClernand on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

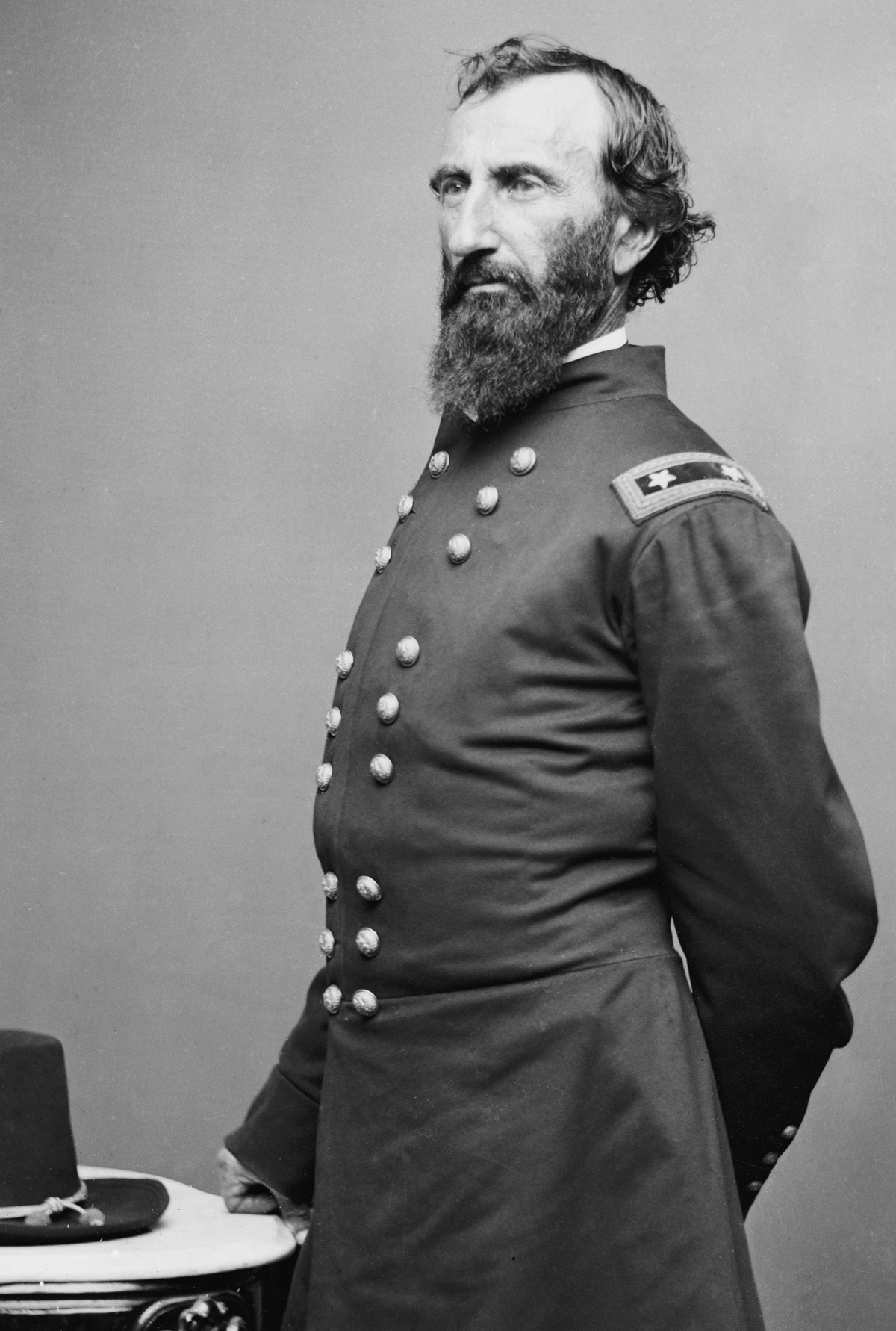

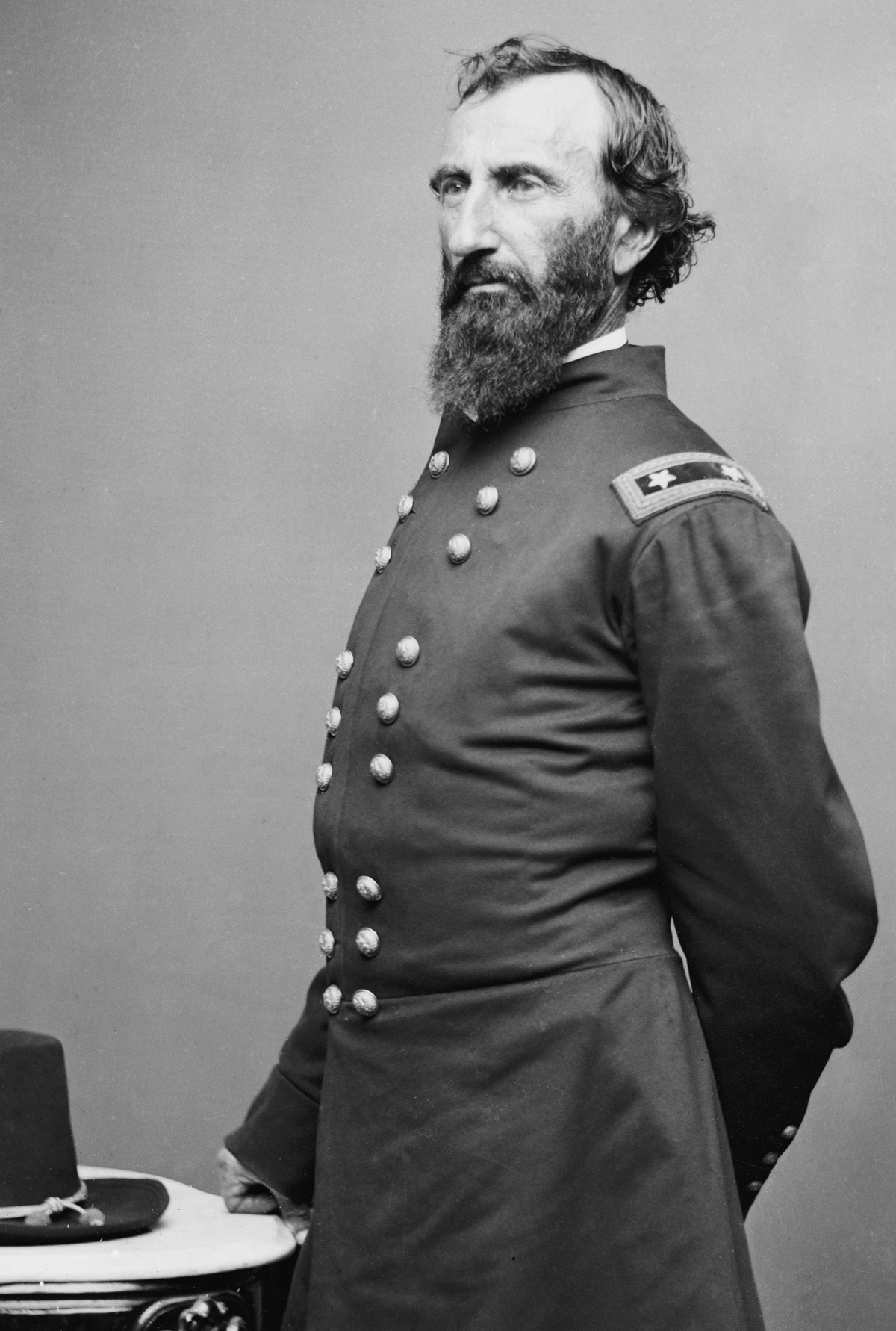

John Alexander McClernand (May 30, 1812 – September 20, 1900) was an American lawyer and politician, and a

Upon the outbreak of the

Upon the outbreak of the

McClernand's service as a major general was tainted by political maneuvering, which was resented by his colleagues. He communicated directly with his commander-in-chief, President Lincoln, offering his criticisms of the strategies of other generals, including Major General

McClernand's service as a major general was tainted by political maneuvering, which was resented by his colleagues. He communicated directly with his commander-in-chief, President Lincoln, offering his criticisms of the strategies of other generals, including Major General

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

general in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. He was a prominent Democratic politician in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and a member of the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

before the war. McClernand was firmly dedicated to the principles of Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

and supported the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

.

McClernand was commissioned a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

of volunteers in 1861. His was a classic case of the politician-in-uniform coming into conflict with career Army officers, graduates of the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

. He served as a subordinate commander under Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

in the Western Theater, fighting in the battles of Belmont, Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

, and Shiloh in 1861–62.

A friend and political ally of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, McClernand was given permission to recruit a force to conduct an operation against Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vi ...

, which would rival the effort of Grant, his department commander. Grant was able to neutralize McClernand's independent effort after it conducted an expedition to win the Battle of Arkansas Post

The Battle of Arkansas Post, also known as Battle of Fort Hindman, was fought from January 9 to 11, 1863, near the mouth of the Arkansas River at Arkansas Post, Arkansas, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Confederat ...

, and McClernand became the senior corps commander in Grant's army for the Vicksburg Campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate States of America, Confederate-controlled ...

in 1863. During the Siege of Vicksburg

The siege of Vicksburg (May 18 – July 4, 1863) was the final major military action in the Vicksburg campaign of the American Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Mis ...

, Grant relieved McClernand of his command by citing his intemperate and unauthorized communication with the press, finally putting an end to a rivalry that had caused Grant discomfort since the beginning of the war. McClernand left the Army in 1864 and served as a judge and a politician in the postbellum era.

Early life and political career

McClernand was born inBreckinridge County, Kentucky

Breckinridge County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 20,432. Its county seat is Hardinsburg, Kentucky. The county was named for John Breckinridge (1760–1806), a Kentucky Attorney ...

, near Hardinsburg, on May 30, 1812, but in 1816, his family moved to Shawneetown, Illinois.Warner, p. 293.John H. Eicher, p. 372. His early life and career were similar to that of another Illinois lawyer of the time, Abraham Lincoln, with whom he was a friend.Hughes, p. 9. Largely self-educated, he was admitted to the Illinois bar

Bar or BAR may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bar (establishment), selling alcoholic beverages

* Candy bar

* Chocolate bar

Science and technology

* Bar (river morphology), a deposit of sediment

* Bar (tropical cyclone), a layer of cloud

* Bar ( ...

in 1832. In that same year he served as a volunteer private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

in the Blackhawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crossed ...

(Lincoln briefly served as a captain.)

In 1835 McClernand founded the ''Shawneetown Democrat'' newspaper, which he edited. As a Democrat he served in 1836 and from 1840 to 1843 in the Illinois House of Representatives

The Illinois House of Representatives is the lower house of the Illinois General Assembly. The body was created by the first Illinois Constitution adopted in 1818. The House under the current constitution as amended in 1980 consists of 118 re ...

.

He served in the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

from March 4, 1843 until March 3, 1851. A bombastic orator, his political philosophy was based on Jacksonian principles. McClernand vigorously opposed the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

when it was introduced in 1846, 1847 and 1848. He disliked abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

which generated favor among his constituents, many of whom were originally natives of slaveholding states.Sifakis, p. 408 Nonetheless, historian Allan Nevins described him as a general favorite in Congress in 1850 as being a man of courtesy and urbanity.Nevins, ''Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny: 1847–1852''. Vol. I., p. 303. On the other hand, John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was U ...

later described him as "a vain, irritable, overbearing, exacting man."Hughes, p. 12. Nevins himself described McClernand in 1861 as an independent brigadier with "a headlong, testy, irascible manner." He was an important ally to Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas played a crucial role in formulating the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

, and McClernand served as a liaison for him the House of Representatives during the debate over the proposed compromise. McClernand also served as Chairman of the Committee on Public Lands from 1845 to 1847 and on the Committee on Foreign Affairs from 1849 to 1851. In 1850, McClernand declined to be a candidate for renomination, and his term expired in 1851. In the eight years he was out of Congress, he developed a large law practice and engaged in land speculation.

In 1859, McClernand was again elected to the House to fill a vacancy caused by the death of Thomas L. Harris. His term began on November 8. He was a strong Unionist and introduced the resolution of July 15, 1861, pledging money and men to the national government. In 1860 he was defeated in a bid for the speakership of the House of Representatives. The small coalition of Democratic representatives from Alabama and South Carolina opposing him objected to his moderate views on slavery and the importance of retaining the Union.

McClernand supported the campaign of his friend, Stephen Douglas, in the 1860 presidential election. He served as one of his campaign managers during the divisive Democratic presidential nomination convention held in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

in 1860.

In November 1842, McClernand married Sarah Dunlap of Jacksonville, Illinois, a close friend of Mary Todd Lincoln

Mary Ann Todd Lincoln (December 13, 1818July 16, 1882) served as First Lady of the United States from 1861 until the assassination of her husband, President Abraham Lincoln in 1865.

Mary Lincoln was a member of a large and wealthy, slave-owning ...

. Sarah was a daughter of James Dunlap,David J. Eicher, p. 218. who served as a quartermaster

Quartermaster is a military term, the meaning of which depends on the country and service. In land armies, a quartermaster is generally a relatively senior soldier who supervises stores or barracks and distributes supplies and provisions. In ...

in the Union Army during the Civil War, resigning as lieutenant colonel and quartermaster of the XIII Corps of the Army of the Tennessee on June 11, 1864.On December 11, 1866, President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

nominated Dunlap for appointment to the grade of brevet brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

of volunteers to rank from March 13, 1865. The appointment was confirmed by the United States Senate on February 6, 1867. John H. Eicher, p. 744. John and Sarah's son, Edward John McClernand, was notable as a West Point graduate in 1870 U.S. Army brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

in the Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

, Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of val ...

recipient and later fought in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. After Sarah's death on May 8, 1861, McClernand married her sister, Minerva Dunlap on December 23, 1862.

Civil War

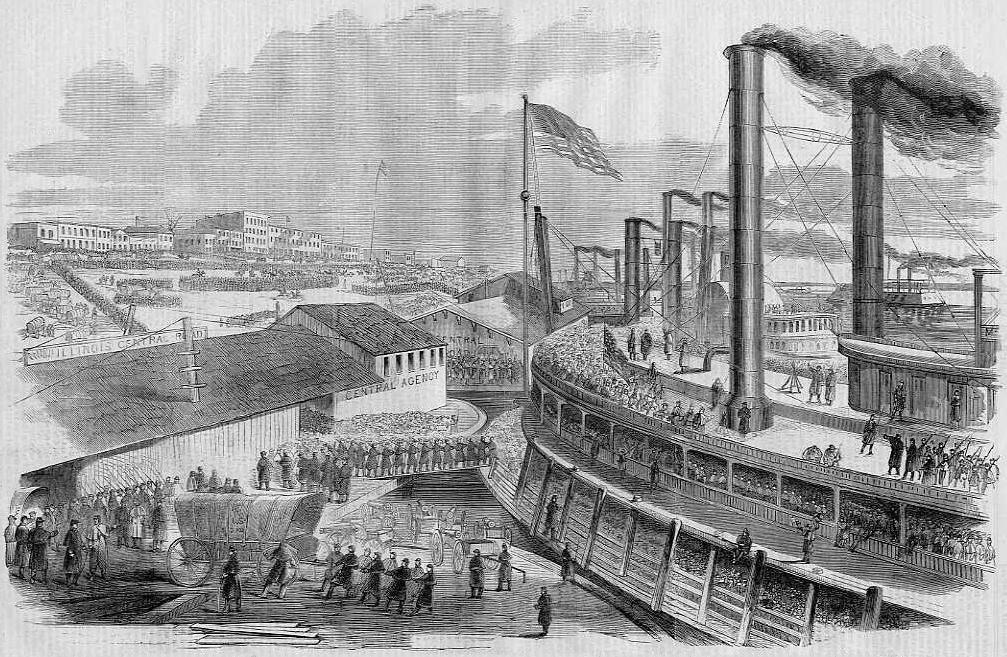

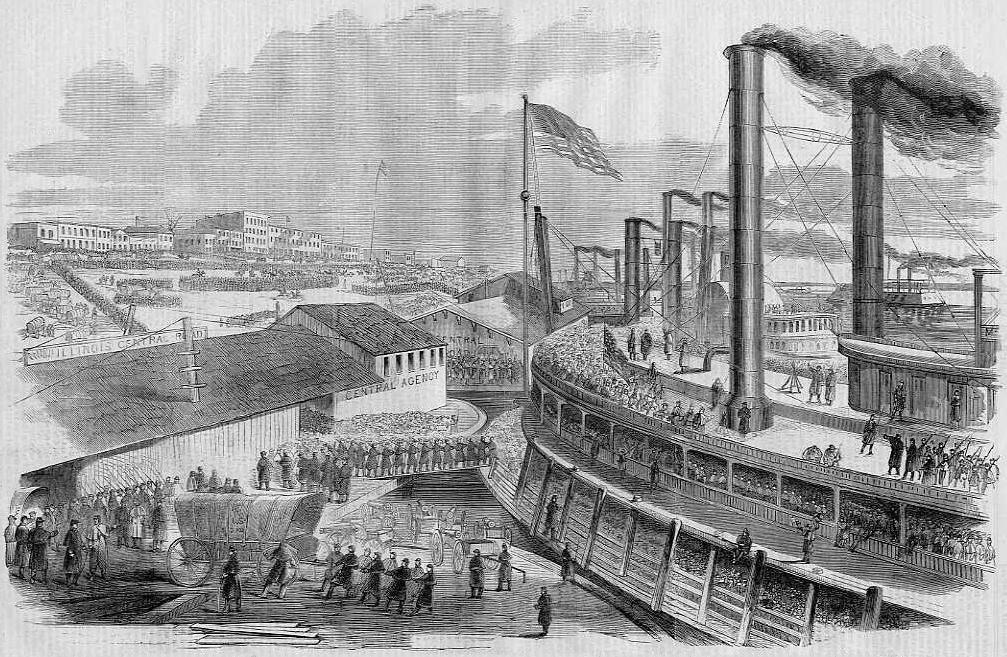

McClernand's Brigade at Cairo

Upon the outbreak of the

Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, McClernand raised the "McClernand Brigade" in Illinois, and was appointed brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

of volunteers on August 7, 1861 to rank from May 17, 1861. His commission as a general was based on Lincoln's desire to retain political connections with the Democrats of Southern Illinois, not on his brief service as a private in the Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", cross ...

. McClernand eventually resigned his Congressional seat effective October 28, 1861. He was an effective recruiter of volunteers for the Union Army. He raised the McClernand Brigade from southern Illinois, an area of mixed sentiments with respect to preservation of the Union. The brigade was placed in the Western Department which was under the command of Major General John C. Fremont

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

on August 21, 1861.Kiper, 28. At the same time, the brigade was placed in the District of Southeast Missouri commanded by Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, a subordinate of Fremont. In the summer of 1861, McClernand commanded and trained his brigade at Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the capital of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat and largest city of Sangamon County. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city, the second largest ...

and Jacksonville, Illinois

Jacksonville is a city in Morgan County, Illinois, United States. The population was 19,446 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Morgan County. It is home to Illinois College, Illinois School for the Deaf, and the Illinois School for ...

, moving them to Cairo, Illinois

Cairo ( ) is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County.

The city is located at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Fort Defiance, a Civil War camp, was built here in 1862 by Union General Ulysse ...

at the beginning of September. The brigade soon began to cut off shipments of arms and supplies to the Confederacy.

Battle of Belmont

McClernand was second in command underUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

at the Battle of Belmont

The Battle of Belmont was fought on November 7, 1861 in Mississippi County, Missouri. It was the first combat test in the American Civil War for Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the future Union Army general in chief and eventual U.S. president, ...

in Missouri on November 7, 1861. In response to orders from Fremont on November 2 and 3, 1861, Grant sent regiments from his district in seven columns to demonstrate against Confederate forces on both sides of the Mississippi River. The objective was to prevent Confederate reinforcement of other Confederate units in Missouri and Arkansas. On the afternoon of November 6, two brigades under Grant's direct command moved down the river. One was commanded by McClernand; the other by Colonel Henry Dougherty.Hughes, 48-59.Kiper, 42. Grant picked up two regiments before stopping overnight, bringing his force to 3,119 men. His plan was to launch a surprise attack on the Confederate camp at Belmont, Missouri

Belmont is an extinct town in Mississippi County, on the eastern border of the U.S. state of Missouri at the Mississippi River. The GNIS classifies it as a populated place under the name "Belmont Landing".

History

Belmont was platted in 1853, and ...

with part of his force while other regiments from his command were moving to attack the Confederates under Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson

Brigadier-General M. Jeff Thompson (January 22, 1826 – September 5, 1876), nicknamed "Swamp Fox," was a senior officer of the Missouri State Guard who commanded cavalry in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. The () w ...

, then at Bloomfield, Missouri and to reinforce Union Colonel Richard Oglesby

Richard James Oglesby (July 25, 1824April 24, 1899) was an American soldier and Republican politician from Illinois, The town of Oglesby, Illinois, is named in his honor, as is an elementary school situated in the Auburn Gresham neighborho ...

operating in southeastern Missouri.

Near 8:00 a.m. on November 7, Grant's force began to disembark from transports about three and one-half miles (5.6 km) north of Belmont, out of range of Confederate artillery batteries across the river at Columbus, Kentucky

Columbus is a home rule-class city in Hickman County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 170 at the 2010 census, a decline from 229 in 2000. The city lies at the western end of the state, less than a mile from the Mississippi Ri ...

. Union gunboats made futile attempts to attack Confederate artillery batteries during the landings. The Confederate camp at Belmont, named Camp Johnston, had been established by Confederate Major General Leonidas Polk

Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864) was a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana and founder of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which separated from the Episcopal Ch ...

as an observation post. When Polk learned of Grant's movement early on November 7, he sent four regiments under Brigadier General Gideon Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806 – October 8, 1878) was an American lawyer, politician, speculator, slaveowner, United States Army major general of volunteers during the Mexican–American War and Confederate brigadier general in the Ameri ...

from Columbus to Belmont as reinforcements to intercept Grant's force.

After his troops had disembarked from the gunboats, McClernand led his brigade toward the Confederate line formed in part by the recently arrived regiments of Gideon Pillow, about 3,000 men in total. By 10:00 a.m., McClernand's skirmishers began to encounter the Confederate skirmishers. McClernand extended his battle line to outflank the Confederate line.Kiper, 44. A gap in the Union line was covered by two regiments shifting to the right. When McClernand saw that one of his regiments under Colonel Napoleon Buford had outflanked the Confederate line, McClernand ordered a general attack. Some Confederate battalions began to run out of ammunition. By 2:00 p.m. the Union battle line broke the Confederate battle line about one mile (1.6 km) from the Confederate camp.

After the Confederate soldiers fled in panic beyond the camp, the Union soldiers took the camp and as their discipline began to break down, they began a disorderly celebration and plundering.Kiper, 45. McClernand walked to the center of the camp and called for three cheers adding to the disorder at the scene. Grant had to order the camp burned to stop the plundering and restore order to the troops.David J. Eicher, 145. At Columbus, Polk got word of the battle and first sent reinforcements, then crossed the river himself with more reinforcements. After about one-half hour of unopposed disorder at the camp, the Confederate reinforcements along with reformed elements of Pillow's regiments routed the Union force, sending them retreating toward their gunboats, which provided covering fire. McClernand had directed artillery placement which also facilitated the Union force's retreat. During the withdrawal McClernand suffered a grazing head wound. When reaching the shore, McClernand acted promptly to cover the boarding of the gunboats and to rescue a Union regiment which had been left behind. The Union troops, including Grant as the last to board a boat, narrowly escaped.

Battle of Fort Donelson

McClernand commanded the 1st Division of Grant's army atFort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

. On the night of February 14, 1862, Confederate commanders decided to break out of the Union Army encirclement of the fort achieved the previous day. McClernand's division, whose flank was not sufficiently covered, was struck by a surprise attack in the early morning on February 15, 1862, the third day of the battle, in bitterly cold weather. By 7:00 a.m., the Confederates in line of battle and covered by artillery attacked McClernand's position, which McClernand thought he would still have time to adjust without Confederate movement in the frigid weather. Within an hour of the Confederate attack, the Confederates had cleared Union cavalry from their front and outflanked Colonel John McArthur's poorly placed brigade.Cooling, p. 169. Low on ammunition and with the negative effect on the men of Colonel Michael Lawler's wounding, McArthur's men began to run from the field. A friendly fire incident contributed to further Union withdrawal and opened two roads for Confederate escape. Yet the Confederate close order tactics in moving forward, an effort to reduce a salient at a road junction and straggling slowed the Confederate advance. By 1:00 p.m. McClernand's division had been thoroughly routed. Without orders from Grant, Brigadier General Lew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

sent his brigades to a new position to block the Confederate exit. Grant then ordered Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith

Charles Ferguson Smith (April 24, 1807 – April 25, 1862) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War and as a Union General in the American Civil War.

Early life and career

Charles Ferguson Smith was born ...

("C.F. Smith") to take the fort after surmising it would now be lightly defended and the Confederates could be encircled. With such men from McClernand's brigade who could be rallied, Wallace moved to retake the lost ground. As night was falling, he had to stop the movement until morning which allowed McClernand's men to gradually return to their campsites. Overnight, the Confederate generals decided to surrender, although Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was a prominent Confederate Army general during the American Civil War and the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealt ...

escaped with most of his cavalrymen and Generals Gideon Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806 – October 8, 1878) was an American lawyer, politician, speculator, slaveowner, United States Army major general of volunteers during the Mexican–American War and Confederate brigadier general in the Ameri ...

and John B. Floyd

John Buchanan Floyd (June 1, 1806 – August 26, 1863) was the 31st Governor of Virginia, U.S. Secretary of War, and the Confederate general in the American Civil War who lost the crucial Battle of Fort Donelson.

Early family life

John Buc ...

fled by boat. On March 21, 1862, McClernand, who had boasted about and exaggerated the achievements of his division was promoted to major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

of volunteers for his service at Fort Donelson.Cooling, p. 251.

Battle of Shiloh

At theBattle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

on April 6–7, 1862, McClernand commanded the First Division of the Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

. On April 5, 1863, McClernand responded to rumors and reports that the Confederates were preparing a surprise attack by sending out a cavalry party to scout but they did not go in the right direction or far enough in any event. In the early morning of April 6, 1863, the regiment of Brigadier General William T. Sherman's Fifth Division on the left flank, stationed about a quarter-mile south and east of Shiloh Church, began to give way under Confederate attack and the colonel's panic.Cunningham, p. 169. McClernand had already begun to send troops forward to prevent Sherman's division from being outflanked. By 9:30 a.m., Sherman's division was being attacked by six Confederate brigades. After two hours of heavy fighting, Sherman's division fell back, despite some reinforcements from Brigadier General W. H. L. Wallace

William Hervey Lamme Wallace (July 8, 1821 – April 10, 1862), more commonly known as W.H.L. Wallace, was a lawyer and a Union general in the American Civil War, considered by Ulysses S. Grant to be one of the Union's greatest generals.

Early ...

's Second Division. About 10:00 a.m., Sherman's and McClernand's divisions linked up in a new position. McClernand's division was organized but Sherman's men reached the new line only a few minutes before the Confederates. Sherman's and McClernand's divisions were pushed back through the "Hornet's Nest", but held a firm line at Pittsburgh Landing as night fell. With the help of reinforcements Grant routed the Confederates with a devastating counterattack on April 7.

Political Maneuvering

McClernand's service as a major general was tainted by political maneuvering, which was resented by his colleagues. He communicated directly with his commander-in-chief, President Lincoln, offering his criticisms of the strategies of other generals, including Major General

McClernand's service as a major general was tainted by political maneuvering, which was resented by his colleagues. He communicated directly with his commander-in-chief, President Lincoln, offering his criticisms of the strategies of other generals, including Major General George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

's in the Eastern Theater and Grant's in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

.

In October 1862, McClernand used his political influence with Illinois Governor

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

Richard Yates to obtain a leave of absence to visit Washington, D.C. and President Lincoln, hoping to receive an important independent command. Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

agreed to order him north to raise troops for the expedition against Vicksburg which he initially would lead.

Battle of Milliken's Bend; Battle of Arkansas Post

Early in January 1863, atMilliken's Bend

The Battle of Milliken's Bend was fought on June 7, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign during the American Civil War. Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army had placed the strategic Mississippi River city of Vicksburg, Mississipp ...

, McClernand superseded Sherman as the leader of the Union force that was to move down the Mississippi as part of the Vicksburg campaign. At Sherman's suggestion, McClernand led an expedition up the Red River to capture the Confederates' Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post, Arkansas The Battle of Arkansas Post

The Battle of Arkansas Post, also known as Battle of Fort Hindman, was fought from January 9 to 11, 1863, near the mouth of the Arkansas River at Arkansas Post, Arkansas, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. Confederat ...

, also known as Battle of Fort Hindman, was fought from January 9 to 11, 1863, near the mouth of the Arkansas River. On January 11, 1863, Arkansas Post

The Arkansas Post (french: Poste de Arkansea) ( Spanish: ''Puesto de Arkansas''), formally the Arkansas Post National Memorial, was the first European settlement in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and present-day U.S. state of Arkansas. In ...

fell to the Union force. Sherman and acting Rear Admiral David D. Porter later convinced a disapproving Grant that leaving the Confederate garrison at Arkansas Post in place could have been an obstacle to the capture of Vicksburg.

Reduced to Corps Command; Friction and Intrigue

On January 17, Grant, after receiving the opinion ofAdmiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

David Dixon Porter

David Dixon Porter (June 8, 1813 – February 13, 1891) was a United States Navy admiral and a member of one of the most distinguished families in the history of the U.S. Navy. Promoted as the second U.S. Navy officer ever to attain the rank of ...

and General Sherman that McClernand was incompetent to lead further operations, united a part of his own troops with those of McClernand and assumed command in person and reduced McClernand to corps command. Three days later he ordered McClernand back to Milliken's Bend. During the rest of the Vicksburg Campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate States of America, Confederate-controlled ...

there was much friction between McClernand and his colleagues. He intrigued for the removal of Grant, spreading rumors to the press of Grant drinking on the campaign.

Attempts to Approach Vicksburg

McClernand landed his men on the Mississippi River levee at Young's Point, where they "suffered from the heavy winter rains and lack of shelter. Tents were not issued to the troops because they were within range of the onfederateguns at Vicksburg; so the more enterprising men dug holes in the levee and covered them with their black rubber blankets. Floundering in knee-deep black mud and still exhausted from recent expeditions, numerous soldiers fell sick. Many cases ofsmallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

were reported. Hospital tents lined the back side of the levee and were crowded with thousands of sick men. Many died, and soon the levee was lined with new graves."

Battle of Champion Hill; Attack on Vicksburg; Relief from Command

It was Grant's opinion that atChampion Hill

Champion Hill is a football stadium in East Dulwich in the London Borough of Southwark. It is the home ground of Dulwich Hamlet.

History

Dulwich Hamlet began playing at the ground in 1912. 'The Hill' was formerly one of the largest amateur grou ...

(May 16, 1863) McClernand was dilatory, but Grant bided his time, waiting for insubordination that was blatant enough to justify removing his politically powerful rival. After a bloody and unsuccessful assault against the Vicksburg entrenchments (ordered by Grant), McClernand wrote a congratulatory order to his corps, which also disparaged the efforts of the other corps.Miller, p. 459. This was published in the press, contrary to an order of the department and another of Grant that official papers were not to be published. McClernand was relieved of his command on June 19, 1863, two weeks before the fall of Vicksburg, and was replaced by Major General Edward O. C. Ord. The duty of notifying him of his dismissal fell to Lieutenant Colonel James H. Wilson, who'd held a grudge against him for an earlier chastising.Miller, p. 460-461. Once McClernand read the order, he exclaimed in shock "I am relieved!" Then seeing the look on Wilson's face, he made a joke out if it by saying "By God sir, we are both relieved!". Grant's order relieving him ordered him to go to any place in Illinois and contact the War Department for new orders.

Field Command in Gulf; Illness and Resignation; Lincoln's Funeral

President Lincoln, who saw the importance of conciliating a leader of the Illinois War Democrats, restored McClernand to a field command in 1864. On February 20, 1864 McClernand returned to his old XIII Corps, now part of the Department of the Gulf. Illness (malaria) limited his role. By the time the Red River Campaign commenced, McClernand had been replaced in command byThomas E. G. Ransom

Thomas Edwin Greenfield Ransom (November 29, 1834 – October 29, 1864) was a surveyor, civil engineer, real estate speculator, and a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Biography

Ransom was born in Norwich, Vermont, son o ...

. From April 27, 1864 through May 1, 1864, McClernand returned to the field to command the detachment of two divisions from the XIII Corps participating in the Red River Campaign. He resigned from the Army on November 30, 1864. McClernand rode on the funeral train of President Lincoln from Washington to Springfield Illinois, which departed from Washington on April 23, 1865 and arrived in Springfield on May 3, 1865.Kiper p. 292. There were eight divisions in Lincoln's funeral procession on May 4, 1865. McClernand was at the front of the second division which preceded the hearse.

Postbellum life

In 1871, at the 17th AnnualIllinois State Fair

The Illinois State Fair is an annual festival, centering on the theme of agriculture, hosted by the U.S. state of Illinois in the state capital, Springfield. The state fair has been celebrated almost every year since 1853. Currently, the fair ...

, McClernand's colt, Zenith, won first place in the "Best Stallion Colt, 2 Years Old" category. The prize was $25. McClernand served as district judge of the Sangamon (Illinois) District from 1870 to 1873, and was chairman of the 1876 Democratic National Convention

The 1876 Democratic National Convention assembled in St. Louis just nine days after the conclusion of the Republican National Convention in Cincinnati.

This was the first political convention held west of the Mississippi River. St. Louis was noti ...

, which nominated Samuel J. Tilden for President of the United States.

McClernand's last public service was on a federal advisory commission overseeing the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

, beginning in 1886. The commissioners met in Utah about 170 days per year and McClernand returned home to Springfield when the commission was not in session. In 1887, the commission recommended that Utah not be admitted as a state until the Mormons had "abandoned polygamy in good faith." The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

issued a proclamation renouncing polygamy in 1890, which McClernand stated he thought was sincere in an 1891 report but in 1892 the majority of the commission issued a report expressing doubt that the polygamy situation had changed. In April 1894, as a non-resident of Utah, McClernand was required by an 1893 law to resign from the Utah Commission.Kiper, p. 300. Utah was admitted to the Union on January 4, 1896 only after polygamy had been outlawed by the state constitution.

Despite his resignation from the Army in 1864, McClernand, no longer a wealthy a wealthy man, was granted an Army pension in 1896, increased in 1900 to $100.00 per month, under acts of Congress.

Having been in ill health for several years, John McClernand died in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the capital of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat and largest city of Sangamon County. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city, the second largest ...

on September 20, 1900.Kiper, p. 302. He is interred there at Oak Ridge Cemetery

Oak Ridge Cemetery is an American cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

The Lincoln Tomb, where Abraham Lincoln, his wife and all but one of their children lie, is here, as are the graves of other prominent Illinois figures. Thus, it is the seco ...

.

In popular culture

McClernand is the villain ofMacKinlay Kantor

MacKinlay Kantor (February 4, 1904 – October 11, 1977), born Benjamin McKinlay Kantor, was an American journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He wrote more than 30 novels, several set during the American Civil War, and was awarded t ...

alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alte ...

book ''If the South Had Won the Civil War

''If the South Had Won the Civil War'' is a 1961 alternate history book by MacKinlay Kantor, a writer who also wrote several novels about the American Civil War. It was originally published in the November 22, 1960, issue of '' Look'' magazine. ...

''. In the alternate history presented, General Grant was killed accidentally at the start of the Vicksburg Campaign. McClernand then insisted upon assuming command and by thoroughly bad generalship managed to lose the campaign, get the Army of the Tennessee almost completely destroyed, and contribute significantly to the Union losing the entire war and the Confederacy gaining independence.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

References

Notes Footnotes Bibliography * Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. ''Forts Henry and Donelson: The Key to the Confederate Heartland''. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987. . * Cunningham, O. Edward. ''Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862''. Edited by Gary Joiner and Timothy Smith. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. . * Eicher, David J. ''The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War.'' New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs, Jr. ''The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. . * Kiper, Richard L. ''Major General John Alexander McClernand: Politician in Uniform''. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999. . * McDonough, James Lee. ''Shiloh – in Hell Before Midnight''. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1977. . * Miller, Donald L. ''Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign That Broke the Confederacy''. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2020. . First published in hardcover 2019. * Nevins, Allan. ''Ordeal of the Union: Fruits of Manifest Destiny: 1847–1852''. Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947. . * Nevins, Allan. ''The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War 1859–1861''. Vol. II. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1950. . * Nevins, Allan. ''The War for the Union''. Vol. 1, ''The Improvised War 1861 – 1862''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959. . * Potter, David M. completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher ''The Impending Crisis: America Before the Civil War, 1848 – 1861''. New York: Harper Perennial, reprint 2011. First published New York: Harper Colophon, 1976. . * Reynolds, John P., "Transactions of the Illinois State Agricultural Society, with Reports from County and District Agricultural Societies". Springfield, Illinois: Illinois Journal Printing Office, 1871. * Sifakis, Stewart. ''Who Was Who in the Civil War.'' New York: Facts On File, 1988. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Winters, John D. ''The Civil War in Louisiana'', Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963. . * Woodworth, Steven E. ''Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. . *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:McClernand, John Alexander 1812 births 1900 deaths People from Breckinridge County, Kentucky American people of the Black Hawk War Union Army generals People of Illinois in the American Civil War Democratic Party members of the Illinois House of Representatives People from Shawneetown, Illinois Politicians from Springfield, Illinois Illinois Jacksonians Illinois lawyers Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois 19th-century American politicians